Original, population-based estimates of indicators of long-term survival and cure in cancer patients are provided. More than a quarter of cancer patients in Italy have reached death rates similar to those of the general population. Nearly three quarters of them will not die as a result of cancer. These estimates are potentially helpful to health-care planners, clinicians, and patients.

Keywords: survival, prevalence, cancer cure, Italy

Abstract

Background

Persons living after a cancer diagnosis represent 4% of the whole population in high-income countries. The aim of the study was to provide estimates of indicators of long-term survival and cure for 26 cancer types, presently lacking.

Patients and methods

Data on 818 902 Italian cancer patients diagnosed at age 15–74 years in 1985–2005 were included. Proportions of patients with the same death rates of the general population (cure fractions) and those of prevalent patients who were not at risk of dying as a result of cancer (cure prevalence) were calculated, using validated mixture cure models, by cancer type, sex, and age group. We also estimated complete prevalence, conditional relative survival (CRS), time to reach 5- and 10-year CRS >95%, and proportion of patients living longer than those thresholds.

Results

The cure fractions ranged from >90% for patients aged <45 years with thyroid and testis cancers to <10% for liver and pancreatic cancers of all ages. Five- or 10-year CRS >95% were both reached in <10 years by patients with cancers of the stomach, colon–rectum, pancreas, corpus and cervix uteri, brain, and Hodgkin lymphoma. For breast cancer patients, 5- and 10-year CRSs reached >95% after 19 and 25 years, respectively, and in 15 and 18 years for prostate cancer patients. Five-year CRS remained <95% for >25 years after cancer diagnosis in patients with liver and larynx cancers, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, and leukaemia. Overall, the cure prevalence was 67% for men and 77% for women. Therefore, 21% of male and 31% of female patients had already reached 5-year CRS >95%, whereas 18% and 25% had reached 10-year CRS >95%.

Conclusions

A quarter of Italian cancer patients can be considered cured. This observation has a high potential impact on health planning, clinical practice, and patients' perspective.

introduction

In the first decade of the 2000s, persons living after a cancer diagnosis represented 4% of the whole population in high-income countries [1–3], and >60% of cancer patients survived longer than 5 years after diagnosis [1, 2].

Standard survival indicators, namely 5- or 10-year relative survival (RS) [4, 5], do not differentiate patients who, in the long-term, will die because of cancer from those who will be cured and will die of other causes [6]. In cancer patients, the risk of death for specific neoplasm is highest in the initial years after diagnosis, and decreases thereafter until a time period when it becomes negligible, and all the surviving patients reach the same life expectancy of the sex- and age-matched general population [7, 8].

The general aim of the present study was to expand the spectrum of indicators of long-term survival and cure among cancer patients, in order to provide helpful information for epidemiologists and health-care planners, as well as for oncologists [9] and patients [7]. Specific aims of this study were to compute: (i) the proportion of cancer cases expected to have the same death rates of the general population (cure fraction); (ii) the number of years after cancer diagnosis necessary to eliminate excess mortality due to cancer (time to cure); (iii) the overall proportion of cancer patients not at risk of dying as a result of cancer (cure prevalence); and (iv) the proportion of prevalent cancer patients who survived longer than ‘time to cure’ and who already reached the same death rates of the general population.

materials and methods

Data collected from 818 902 cancer patients diagnosed at age 15–74 years in 1985–2005 by Italian cancer registries included 454 527 cancer cases diagnosed in men (85 053 lung, 63 047 prostate, and 56 635 colorectal cancers, supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Corresponding numbers in women were 364 375, including 128 004 breast, 41 864 colorectal, and 20 398 endometrial cancers (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Detailed description of statistical methods is provided in supplementary data, available at Annals of Oncology online: extended description of statistical methods. Briefly, the observed RS was calculated for cases diagnosed in 1985–2002 and followed up until 2007, by cancer type, sex, age at diagnosis, and period of diagnosis. RS were also modelled by means of mixture cure models, including continuous age and period of diagnosis effects [1, 10, 11]. Sex-specific model-based survival estimates were also calculated for the overall population (15–74 years), at the average age at diagnosis for each cancer type.

Proportions of patients with the same death rates of the general population (cure fractions, supplementary Figure S1A, available at Annals of Oncology online) were calculated. In addition, we estimated complete prevalence adjusting the observed prevalence in each registry with the completeness index method [1, 11, 12], conditional relative survival (CRS), time to reach 5- and 10-year CRS >95% [13] (supplementary Figure S1B, available at Annals of Oncology online), and proportion of patients living longer than those thresholds (supplementary Figure S1C, available at Annals of Oncology online). Finally, we calculated the proportion of prevalent patients who were not at risk of dying as a result of cancer (cure prevalence, supplementary Figure S1C, available at Annals of Oncology online) [14].

results

Among Italian cancer patients diagnosed at aged 15–74 between 1985 and 2005, the cure fraction was highest in patients <45 years of age for thyroid (99% in women and 95% in men), testis (94%), and corpus uteri (91%). Conversely, cure fractions <10% emerged, for all ages and sexes, for liver and pancreatic cancer patients and, for patients aged 55 years or older, diagnosed with cancers of the lung, gallbladder, brain, and leukaemias (Table 1). Cure fractions were largely higher (by 10% or more) in women than in men for all age groups in patients with cancer of the oral cavity, skin melanoma, kidney, bladder, and thyroid cancers. A less clear advantage (0%–10%) for women emerged for patients with stomach and colorectal cancer, whereas for all other cancer types no difference in cure fraction emerged across age groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated cure fraction by cancer type, sex, and age at diagnosis. aItaly 1985–2005

| Cancer type, ICD10 | Cure fraction (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men, age (years) |

Women, age (years) |

|||||||

| 15–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 15–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | |

| Oral cavity, C01–14 | 42 | 27 | 19 | 13 | 60 | 45 | 37 | 29 |

| Oesophagus, C15 | 16 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| Stomach, C16 | 44 | 31 | 25 | 19 | 42 | 35 | 31 | 28 |

| Colon and rectum, C18–21 | 54 | 50 | 48 | 45 | 57 | 53 | 51 | 49 |

| Liver, C22 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Gallbladder, C23–24 | 26 | 15 | 11 | 7 | 18 | 12 | 9 | 7 |

| Pancreas, C25 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 17 | 7 | 4 | 2 |

| Larynx, C32 | 49 | 39 | 34 | 29 | 49 | 39 | 34 | 29 |

| Lung, C33–34 | 17 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 30 | 16 | 11 | 7 |

| Skin melanoma, C43 | 77 | 67 | 61 | 54 | 85 | 78 | 73 | 68 |

| Connective tissue, C47, C49 | 67 | 54 | 47 | 39 | 60 | 52 | 47 | 43 |

| Breast, C50 | 40 | 60 | 54 | 56 | ||||

| Vagina and vulva, C51–52 | 75 | 60 | 51 | 41 | ||||

| Cervix uteri, C53 | 77 | 64 | 56 | 46 | ||||

| Corpus uteri, C54 | 91 | 83 | 76 | 66 | ||||

| Ovary, C56 | 62 | 40 | 28 | 17 | ||||

| Prostate, C61 | 47 | 49 | 50 | 50 | ||||

| Testis, C62 | 94 | 90 | 86 | 83 | ||||

| Kidney, C64–66, C68 | 65 | 51 | 43 | 35 | 75 | 62 | 55 | 46 |

| Bladder, C67, D09.0, D30.3, D41.4 | 81 | 63 | 50 | 35 | 89 | 75 | 63 | 48 |

| Brain, C70–72 | 35 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 41 | 15 | 7 | 2 |

| Thyroid, C73 | 95 | 75 | 60 | 43 | 99 | 94 | 84 | 65 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma, C81 | 80 | 63 | 38 | 35 | 79 | 74 | 50 | 33 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, C82–85, C96 | 45 | 35 | 30 | 26 | 56 | 40 | 31 | 22 |

| Multiple myeloma, C88–90 | 20 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 35 | 23 | 9 | 12 |

| Leukaemia, C91–95 | 18 | 12 | 9 | 7 | 18 | 12 | 9 | 7 |

aAge 15–74 years.

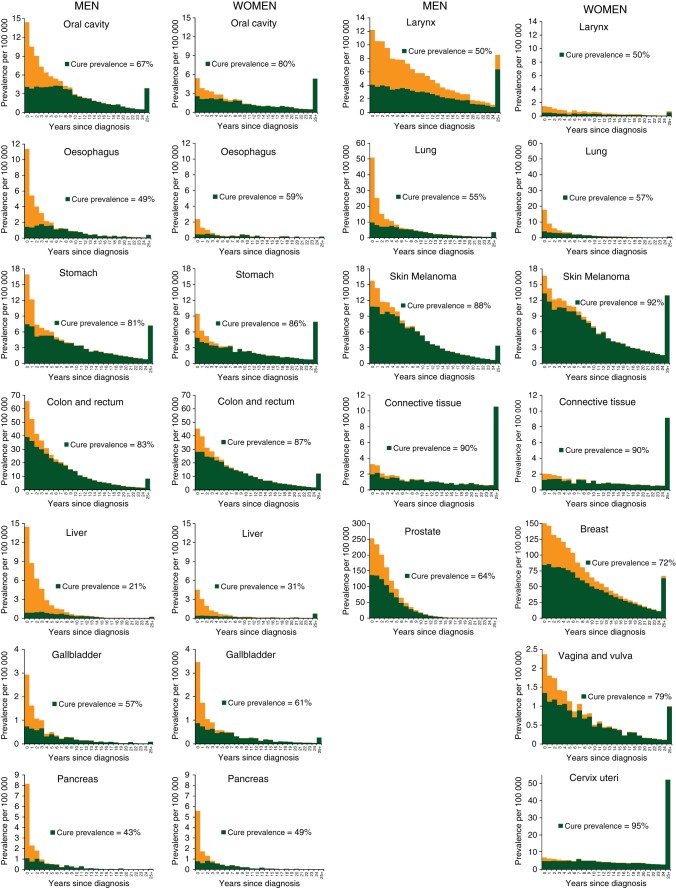

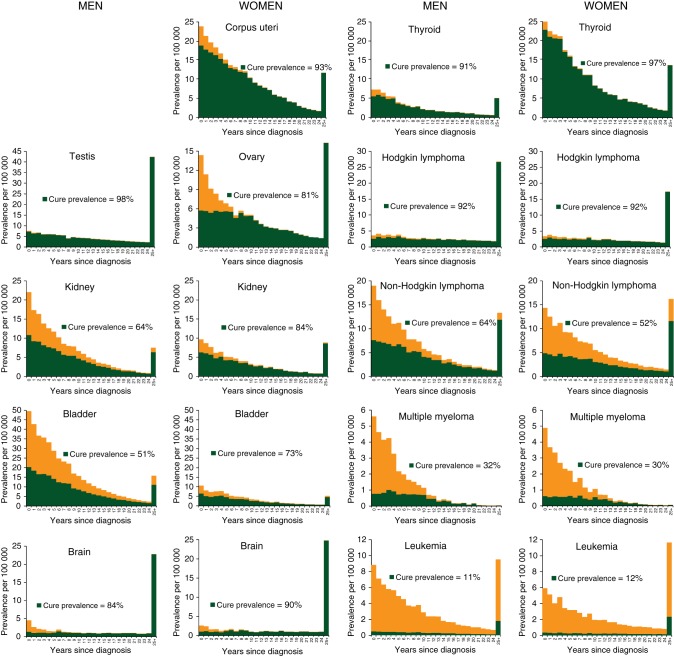

The cure prevalence proportions were particularly high for patients with cancer of testis (98%), thyroid (91% in men and 97% in women), cervix uteri (95%), corpus uteri (93%), and Hodgkin lymphoma (92%, both sexes) (Figure 1). The cure prevalence proportions were 72% for breast cancer patients, 64% for prostate, 83% in men, and 87% in women diagnosed with colorectal cancer, whereas it was less than one-third for patients with liver cancer, myeloma, and leukaemia (Figure 1). The overall cure prevalence proportion for all examined cancer types encompassed 73% (i.e. 67% of men and 77% women) of persons living after cancer diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Overall prevalence and cure prevalence (proportion of cancer patients who will not die of their disease), overall and by year since diagnosis, sex, and cancer type. Italy 1985–2005. At 1 January 2006, in patients aged 15–74 years living after a cancer diagnosis, calculated as a sum of age-specific estimates.

In both sexes, time to cure was reached in <10 years, consistently so for different definitions used, by patients with cancers of the stomach and colon–rectum (both 5–9 years), pancreas (5–6 years), cervix and corpus uteri (5–9 years), and brain (7–8 years). In particular, time to cure was reached in <5 years by women with thyroid cancer and by men with testicular cancer (Table 2). For patients with liver and larynx cancers, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, and leukaemia, time to cure was not reached or it was >15 years for all definitions used. For these cancers, CRS remained <90%, in comparison with the general population, and for 15 years or more after cancer diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimates of time to cure according to different thresholds for 5- and 10-year conditional relative survival (CRS)a by cancer type, sex, and age. Italy 1985–2005

| Cancer type, ICD10 | Age at diagnosisb (years) | Men |

Women |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years to 5-year CRS |

Years to 10-year CRS | Years to 5-year CRS |

Years to 10-year CRS | ||||

| >90% | >95% | >95% | >90% | >95% | >95% | ||

| Oral cavity, C01–14 | 15–44 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 10 |

| 45–54 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 12 | |

| 55–64 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 13 | |

| 65–74 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 13 | |

| 15–74 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | |

| Oesophagus, C15 | 15–74 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| Stomach, C16 | 15–44 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 7 |

| 45–54 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 7 | |

| 55–64 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 8 | |

| 65–74 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 8 | |

| 15–74 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Colon and rectum, C18–21 | 15–44 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 7 |

| 45–54 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 7 | |

| 55–64 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 8 | |

| 65–74 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 8 | |

| 15–74 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 8 | |

| Liver, C22 | 15–74 | 15 | 18 | 20 | 14 | 18 | 19 |

| Gallbladder, C23–24 | 15–74 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 9 |

| Pancreas, C25 | 15–74 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Larynx, C32 | 15–44 | 9 | 22 | >25 | |||

| 45–54 | 14 | >25 | >25 | ||||

| 55–64 | 16 | >25 | >25 | ||||

| 65–74 | 19 | >25 | >25 | ||||

| 15–74 | 17 | >25 | >25 | 17 | >25 | >25 | |

| Lung, C33–34 | 15–44 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

| 45–54 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| 55–64 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 9 | |

| 65–74 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 15–74 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 9 | |

| Skin melanoma, C43 | 15–44 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| 45–54 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 9 | |

| 55–64 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 10 | |

| 65–74 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 11 | |

| 15–74 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 9 | |

| Connective tissue, C47, C49 | 15–74 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 11 |

| Breast, C50 | 15–44 | 14 | >25 | >25 | |||

| 45–54 | 6 | 17 | 24 | ||||

| 55–64 | 9 | 19 | 25 | ||||

| 65–74 | 9 | 17 | 21 | ||||

| 15–74 | 9 | 19 | 25 | ||||

| Vagina and vulva, C51–52 | 15–74 | 8 | 12 | 15 | |||

| Cervix uteri, C53 | 15–44 | 3 | 5 | 6 | |||

| 45–54 | 5 | 7 | 7 | ||||

| 55–64 | 6 | 8 | 8 | ||||

| 65–74 | 6 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| 15–74 | 5 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Corpus uteri, C54 | 15–44 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 45–54 | 2 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| 55–64 | 3 | 6 | 7 | ||||

| 65–74 | 5 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| 15–74 | 4 | 6 | 7 | ||||

| Ovary, C56 | 15–44 | 5 | 7 | 8 | |||

| 45–54 | 7 | 9 | 9 | ||||

| 55–64 | 8 | 10 | 10 | ||||

| 65–74 | 9 | 11 | 11 | ||||

| 15–74 | 8 | 10 | 10 | ||||

| Prostate, C61 | 45–54 | 10 | 15 | 18 | |||

| 55–64 | 10 | 15 | 18 | ||||

| 65–74 | 10 | 15 | 18 | ||||

| 15–74 | 10 | 15 | 18 | ||||

| Testis, C62 | 15–44 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 45–54 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| 15–74 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Kidney, C64–66, C68 | 15–44 | 3 | 8 | 15 | 2 | 5 | 8 |

| 45–54 | 5 | 13 | 22 | 4 | 8 | 11 | |

| 55–64 | 7 | 16 | >25 | 5 | 10 | 13 | |

| 65–74 | 10 | 20 | >25 | 7 | 12 | 15 | |

| 15–74 | 8 | 17 | >25 | 5 | 10 | 14 | |

| Bladder, C67, D09.0, | 15–44 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| D30.3, D41.4 | 45–54 | 2 | 13 | >25 | 1 | 5 | 12 |

| 55–64 | 7 | 22 | >25 | 3 | 11 | 19 | |

| 65–74 | 15 | >25 | >25 | 8 | 18 | >25 | |

| 15–74 | 10 | >25 | >25 | 5 | 14 | 23 | |

| Brain, C70–72 | 15–54 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| Thyroid, C73 | 15–44 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 45–54 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 55–64 | 1 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| 65–74 | 3 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| 15–74 | 1 | 9 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma, C81 | 15–74 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 6 | 11 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, C82–85, C96 | 15–44 | 8 | 15 | 22 | 4 | 14 | 25 |

| 45–54 | 10 | 18 | 25 | 10 | 23 | >25 | |

| 55–64 | 12 | 20 | >25 | 14 | >25 | >25 | |

| 65–74 | 13 | 22 | >25 | 18 | >25 | >25 | |

| 15–74 | 11 | 20 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |

| Multiple myeloma, C88–90 | 55–64 | 18 | 22 | 24 | 24 | >25 | >25 |

| 65–74 | 17 | 20 | 21 | 17 | 21 | 22 | |

| 15–74 | 17 | 20 | 21 | 17 | 21 | 22 | |

| Leukaemia, C91–95 | 15–44 | 25 | >25 | >25 | 25 | >25 | >25 |

| 45–54 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |

| 55–64 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |

| 65–74 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |

| 15–74 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | >25 | |

Italic values stand for all (15–74) ages.

aEstimates are based on the relative survival function for each type and sex parameterized using mixture cure models. ‘One’ year is reported when time to reach thresholds is <1 year; ‘>25’ when threshold is not reached within 25 years.

bEstimates are shown by age groups when overall annual incidence rates >10/100 000.

For other cancer types, the time to reach the different thresholds was heterogeneous according to the definition used. In women with breast cancer, a 5-year CRS >90% was reached before 10 years from diagnosis (14 years for patients aged 15–44), but 5-year CRS >95% in nearly 20 years and 10-year CRS >95% in 25 years or more. For patients with prostate cancer, these times to cure were reached in 10, 15, and 18 years, respectively. Thus, time to reach these thresholds were variable for patients with kidney and bladder cancers. As a consequence (Table 3), proportions of all patients living after a cancer diagnosis who reached time to cure were relatively high in both sexes, and according to different thresholds, for cervix (>70% among 167/100 000 women) and corpus uteri (>50% among 258/100 000 women), testis (>90% among 150/100 000 men), brain (>50% among 56/100 000 men and women), thyroid cancer (>75% among 255/100 000 women), and Hodgkin lymphoma (>50% among 95/100 000 men and 78/100 000 women). Less than 10% of patients with liver, laryngeal, prostate cancers, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, and leukaemia had already reached the same or similar death rates of the general population. Among all Italian women, 1709/100 000 were alive after a breast cancer diagnosis; 41% had already reached 5-year CRS >90%, but only 6% reached 10-year CRS >95%. Similarly, heterogeneity of proportions of cured patients according to the time-to-cure definition emerged for kidney and, most notably, for bladder cancer patients (5-year CRS >90% reached by 29%, whereas 10-year CRS >95% by only 1% among 438/100 000 men). The proportion of patients who reached 5- or 10-year CRS >95% was intermediate for colorectal cancer (30% and 27% among 422/100 000 men; 40% and 36% among 352/100 000 women), stomach cancer (38% and 37% among 109/100 000 men; 58% and 49% among 73/100 000 women), and skin melanoma (49% and 41% among 184/100 000 women) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Complete prevalence (CP)a and proportion (%) of patients who reached different levels of conditional relative survival (CRS)b by cancer type and sex. Italy 1985–2005

| Cancer type, ICD10 | Men |

Women |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | Five-year CRS | Five-year CRS | Ten-year CRS | CP | Five-year CRS | Five-year CRS | Ten-year CRS | |

| ×100 000 | >90% | >95% | >95% | ×100 000 | >90% | >95% | >95% | |

| Oral cavity, C01–14 | 99 | 30% | 23% | 22% | 49 | 43% | 35% | 32% |

| Oesophagus, C15 | 13 | 18% | 15% | 15% | 4 | 29% | 26% | 26% |

| Stomach, C16 | 109 | 47% | 38% | 37% | 73 | 58% | 49% | 47% |

| Colon and rectum, C18–21 | 422 | 41% | 30% | 27% | 352 | 52% | 40% | 36% |

| Liver, C22 | 46 | 1% | 1% | 1% | 16 | 9% | 8% | 7% |

| Gallbladder, C23–24 | 10 | 20% | 14% | 13% | 12 | 26% | 20% | 20% |

| Pancreas, C25 | 17 | 18% | 16% | 16% | 13 | 22% | 19% | 19% |

| Larynx, C32 | 141 | 15% | 0% | 0% | 14 | 14% | 0% | 0% |

| Lung, C33–34 | 174 | 23% | 18% | 17% | 60 | 21% | 17% | 15% |

| Skin melanoma, C43 | 140 | 54% | 38% | 36% | 184 | 76% | 49% | 41% |

| Connective tissue, C47, C49 | 42 | 67% | 58% | 55% | 35 | 70% | 59% | 55% |

| Breast, C50 | 1709 | 41% | 12% | 6% | ||||

| Vagina and vulva, C51–52 | 19 | 40% | 25% | 18% | ||||

| Cervix uteri, C53 | 167 | 82% | 75% | 73% | ||||

| Corpus uteri, C54 | 258 | 71% | 56% | 50% | ||||

| Ovary, C56 | 136 | 51% | 43% | 42% | ||||

| Prostate, C61 | 592 | 4% | 0% | 0% | ||||

| Testis, C62 | 150 | 95% | 94% | 93% | ||||

| Kidney, C64–66, C68 | 181 | 39% | 12% | 2% | 97 | 57% | 36% | 26% |

| Bladder, C67, D09.0, D30.3, D41.4 | 438 | 29% | 5% | 1% | 98 | 58% | 25% | 10% |

| Brain, C70–72 | 57 | 58% | 54% | 53% | 56 | 67% | 63% | 63% |

| Thyroid, C73 | 74 | 74% | 58% | 54% | 255 | 87% | 78% | 78% |

| Hodgkin lymphoma, C81 | 95 | 85% | 65% | 59% | 78 | 88% | 68% | 52% |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, C82–85, C96 | 176 | 31% | 14% | 4% | 159 | 34% | 7% | 1% |

| Multiple myeloma, C88–90 | 35 | 2% | 1% | 0% | 29 | 2% | 1% | 0% |

| Leukaemia, C91–95 | 87 | 7% | 0% | 0% | 69 | 13% | 0% | 0% |

aAt 1 January 2006 in patients aged 15–74 years living after a cancer diagnosis, calculated as a sum of age-specific estimates of prevalence.

bEstimates are based on the relative survival function for each type and sex parameterized using mixture cure models.

Overall, 27% of all cancer patients (21% in men and 31% in women), or 0.9% of the Italian population, had reached 5-year CRS >95% and 22% (18% in men and 25% in women) 10-year RS >95%.

discussion

This study showed that a quarter (27%) of persons living in Italy in the first decade of the 2000s after a cancer diagnosis had reached a death rate similar to that of the general population. In addition, nearly three quarters (73%) of them will not die as a result of their cancer. All the indicators of long-term survival showed a huge heterogeneity by cancer type, age group and, less markedly, by sex.

Present findings for breast cancer patients were in substantial agreement with many previous studies, reporting that a small (i.e. <10%) but significant excess mortality remains at least up to 15 years after diagnosis [13, 15, 16]. However, approximately half of the breast cancer patients will not die as a result of their cancer [6, 17], reaching a negligible excess risk of death after ∼20 years since diagnosis. A similar pattern emerged for men living after a prostate cancer diagnosis [6, 7, 15], while a more favourable long-term survival emerged for colorectal [7, 14, 15, 18] and invasive cervical cancers [7, 13, 19] with cure fractions >50% reached in 8 years. A cure fraction <10% emerged for lung and pancreas cancer patients, and no excess risk of death remained after 9 and 6 years since diagnosis, including 15%–20% of prevalent patients [6, 15, 20]. As elsewhere, the cure prevalence for patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, and leukaemia was <50%, and for these patients excess mortality never became negligible [7, 13, 15].

A substantial advantage in all indicators of long-term cancer survival emerged in women for some cancer types (e.g. colorectal, skin melanoma, bladder, kidney, thyroid, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma) [15, 21], variously attributed to lower prevalence of co-morbidity, earlier stage at diagnosis, and better resistance to disease than men [22]. Moreover, a poorer long-term survival with increasing age was reported for almost all cancer types, possibly due to late recurrences or adverse treatment effects, secondary tumours, or increased co-morbidities [7, 13].

strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting a wide spectrum of validated indicators of long-term survival and cure of cancer, including cure fraction and cure prevalence of particular interests to orient public health policies. In addition, for 26 cancer types (representing 95% and 97% of all cancer incidence in men and women, respectively), we estimated the time to reach the same death rates of the general population, which is of overwhelming importance for cancer patients and oncologists.

Potential limitations of cure models are known and should be considered (supplementary data, available at Annals of Oncology online: extended description of statistical methods) [23]. In general, cure models may not be appropriate for data with too short a follow-up to identify a plateau in the tail [24]. In this scenario, difficulties in identifying model parameters arose (cancer-specific excess mortality did not become negligible) and estimates of time to cure were either longer than the observation time (i.e. leukaemia) or rather sensible to the choice of the CRS threshold (i.e. prostate or breast cancers). However, in the present study, all the used models converged and fittings were graphically assessed (supplementary Figure S2 and Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The accuracy of the present estimates depended also on the size of the study population and on the follow-up length, which, in turn, were the strengths of our study. Indeed, our population-based survival estimates were based on very large cohorts of patients followed up for >20 years after diagnosis in order to maximize the reliability of the survival parameter estimates.

Histological subtype is an important prognostic factor at diagnosis for many neoplasms, particularly for non-Hodgkin lymphoma and leukaemia [25]. Unfortunately, we were not able to calculate survival and prevalence estimates by histological subtypes [1, 7, 26]. We also lacked information on other important prognostic factors, in particular, stage and treatment. Previous reports have shown that stage has a prognostic effect, mainly during the first years after diagnosis, which lessens and can disappear for long-term survival [13].

New therapies, in particular biological treatments for solid tumours and lymphomas, have improved the outcome of cancer patients over time. There is a possibility that, for some neoplasms, adjuvant treatments may prolong survival, but they do not affect lethality [27]. Unfortunately, population-based studies with a long-term follow-up period could hardly allow these stratifications.

RS could be biased when background cancer risk factors (e.g. smoke, HCV) carry a higher risk of related mortalities. This effect has been shown to be negligible for lung cancer [28] and could result in downward RS estimates and in prolonged time to reach the same mortality of the general population.

The generalization of results here presented is also questionable even if Italian RS levels were similar to those of most European countries [5].

Present long-term survival and cancer cure estimates reflected the average survival time of large groups of people (i.e. a population) rather than an individual prognosis. Moreover, they must be interpreted considering that a quantitative estimation of lacking excess mortality is not always the equivalent of well-being. Parallel studies on cancer rehabilitation needs, including indicators of quality of life, are also necessary [29].

The availability of reliable and accurate estimates of long-term survival and cure for the increasing number of persons living many years since cancer diagnosis may be helpful not only to epidemiologists and health-care planners, but also to clinicians in developing guidelines to enhance and standardize the long-term follow-up of cancer survivors [9, 30]. Most of all, they could be helpful to patients dealing with uncertainty about the future, making important life decisions, and supporting their rehabilitation demands.

funding

This work was supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) (grant no. 11859).

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We thank Marilena Bongiovanni and cancer patients' associations stimulating and supporting the study. The authors also thank Maja Pohar Perme and Enzo Coviello for helpful comments, and Mrs Luigina Mei for editorial assistance.

appendix: Members of the AIRTUM Working group

S. Virdone, A. Zucchetto (CRO Aviano National Cancer Institute of Aviano); A. Gigli (Institute for Research on Population and Social Sciences, National Research Council, Rome); S. Francisci (National Institute of Health, Rome); P. Baili, G. Gatta (Foundation IRCSS, National Cancer Institute of Milan); M. Castaing (Integrated Cancer Registry of Catania-Messina-Siracusa-Enna, Catania), R. Zanetti (Piedmont Cancer Registry, Torino); P. Contiero (Varese Cancer Registry, Foundation IRCSS, National Cancer Institute of Milan); E. Bidoli (Friuli Venezia Giulia Cancer Registry); M. Vercelli (Liguria Cancer Registry, Genova); M. Michiara (Parma Cancer Registry); M. Federico (Modena Cancer Registry); G. Senatore (Salerno Cancer Registry); F. Pannozzo (Latina Cancer Registry); M. Vicentini (Reggio Emilia Cancer Registry); A. Bulatko (Alto Adige/Sudtirol Cancer Registry); D. R. Pirino (Sassari Cancer Registry); M. Gentilini (Trento Cancer Registry); M. Fusco (Napoli Cancer Registry); A. Giacomin (Biella Cancer Registry); A. C. Fanetti (Sondrio Cancer Registry); R. Cusimano (Palermo Cancer Registry).

references

- 1.AIRTUM Working Group. Italian cancer figures, report 2010. Cancer prevalence in Italy: Patients living with cancer, long-term survivors and cured patients. Epidemiol Prev. 2010;34(5–6 Suppl 2):1–188. http://www.registri-tumori.it/cms/?q=Rapp2010. (28 August 2014, date last accessed) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parry C, Kent EE, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer survivors: a booming population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1996–2005. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gatta G, Mallone S, van der Zwan JM, et al. Cancer prevalence estimates in Europe at the beginning of 2000. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1660–1666. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman M, Quaresima M, Berrino F, et al. Cancer Survival in five continents: a worldwide population-based study (CONCORD) Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:730–756. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP, et al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE-5—a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:23–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francisci S, Capocaccia R, Grande E, et al. The cure of cancer: a European perspective. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1067–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baade PD, Youlden DR, Chambers SK. When do I know I am cured? Using conditional estimates to provide better information about cancer survival prospects. Med J Aust. 2011;194:73–77. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb04171.x. Erratum in Med J Aust 2011; 194: 376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellison LF, Bryant H, Lockwood G, Shack L. Conditional survival analyses across cancer sites. Health Rep. 2011;22:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. American society of Clinical Oncology Statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:631–640. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Angelis R, Capocaccia R, Hakulinen T, et al. Mixture models for cancer survival analysis: application to population-based data with covariates. Stat Med. 1999;18:441–454. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990228)18:4<441::aid-sim23>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merrill RM, Capocaccia R, Feuer EJ, Mariotto A. Cancer prevalence estimates based on tumour registry data in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:197–207. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capocaccia R, De Angelis R. Estimating the completeness of prevalence based on cancer registry data. Stat Med. 1997;16:425–440. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970228)16:4<425::aid-sim414>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janssen-Heijnen MLG, Gondos A, Bray F, et al. Clinical relevance of conditional survival of cancer patients in Europe: age-specific analyses of 13 cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2520–2528. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Berrino F, et al. Colon cancer prevalence and estimation of differing care needs of colon cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1136–1142. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smastuen M, Aagnes B, Johannsen TB, et al. Long-term Cancer Survival: Patterns and Trends in Norway 1965–2007. Oslo: Cancer Registry of Norway; 2008. http://www.kreftregisteret.no/Global/Publikasjoner%20og%20rapporter/CIN2007_del2.pdf. (28 August 2014, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janssen-Heijnen MLG, van Steenbergen LN, Voogd AC, et al. Small but significant excess mortality compared with the general population for long-term survivors of breast cancer in the Netherlands. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:64–68. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woods LM, Rachet B, Lambert PC, et al. ‘Cure’ from breast cancer among two populations of women followed for 23 years after diagnosis. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1331–1336. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambert PC, Dickman PW, Osterlund P, et al. Temporal trends in the proportion cured for cancer of the colon and rectum: a population-based study using data from the Finnish Cancer Registry. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2052–2059. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrae B, Andersson TML, Lambert PC, et al. Screening and cervical cancer cure: population based cohort study. Br Med J. 2012;344:e900. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinn M, Striefler JK, Sinn BV, et al. Does long-term survival in patients with pancreatic cancer really exist? Results from the CONKO-001 study. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108:398–402. doi: 10.1002/jso.23409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cvancarova M, Aagnes B, Fosså SD, et al. Proportion cured models applied to 23 cancer sites in Norway. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1700–1710. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Micheli A, Ciampichini R, Oberaigner W, et al. The advantage of women in cancer survival: an analysis of EUROCARE-4 data. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1017–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu XQ, De Angelis R, Andersson TM, et al. Estimating the proportion cured of cancer: some practical advice for users. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:836–842. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Othus M, Barlogie B, Leblanc ML, Crowley JJ. Cure models as a useful statistical tool for analyzing survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3731–3736. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersson TML, Lambert PC, Derolf AR, et al. Temporal trends in the proportion cured among adults diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia in Sweden 1973–2001: a population-based study. Br J Haematol. 2009;148:918–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.AIRTUM Working Group. Italian cancer figures, report 2011. Survival of cancer patients in Italy. Epidemiol Prev. 2011;35(Suppl3):1–200. http://www.registri-tumori.it/cms/Rapp2011. (28 August 2014, date last accessed) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies C, Godwin J, et al. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378:771–784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinchliffe SR, Rutheford MJ, Crowter MJ, et al. Should relative survival be used with lung cancer data. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1584–1589. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baili P, Hoekstra-Weebers J, Van Hoof E, et al. Cancer rehabilitation indicators for Europe. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1356–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implication of care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:561–570. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.