Background: Antithrombin III (ATIII), an antiproteinase-inhibiting coagulation, was investigated for roles in host defense.

Results: Extensive proteolysis of ATIII by endogenous and bacterial enzymes generated antimicrobial activity, mapped to helix D of the molecule.

Conclusion: ATIII harbor “cryptic” host defense epitopes released during proteolysis.

Significance: The results explain previously observed antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects of ATIII supplementation during infection.

Keywords: Antithrombin (AT), Bacteria, Heparin, Membrane, Sepsis, Antimicrobial, Antithrombin iii, Peptide

Abstract

Antithrombin III (ATIII) is a key antiproteinase involved in blood coagulation. Previous investigations have shown that ATIII is degraded by Staphylococcus aureus V8 protease, leading to release of heparin binding fragments derived from its D helix. As heparin binding and antimicrobial activity of peptides frequently overlap, we here set out to explore possible antibacterial effects of intact and degraded ATIII. In contrast to intact ATIII, the results showed that extensive degradation of the molecule yielded fragments with antimicrobial activity. Correspondingly, the heparin-binding, helix d-derived, peptide FFFAKLNCRLYRKANKSSKLV (FFF21) of human ATIII, was found to be antimicrobial against particularly the Gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Fluorescence microscopy and electron microscopy studies demonstrated that FFF21 binds to and permeabilizes bacterial membranes. Analogously, FFF21 was found to induce membrane leakage of model anionic liposomes. In vivo, FFF21 significantly reduced P. aeruginosa infection in mice. Additionally, FFF21 displayed anti-endotoxic effects in vitro. Taken together, our results suggest novel roles for ATIII-derived peptide fragments in host defense.

Introduction

Antithrombin III (ATIII)2 is a glycoprotein that is synthesized in the liver and circulates in plasma at a concentration of ∼290 μg/ml (5 μm). ATIII is a serine protease inhibitor and inactivates thrombin and other serine proteases of the coagulation cascade (1). Patients with septic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation present reduced ATIII levels in plasma (2, 3), mainly due to consumption during coagulation and extravascular leakage (1, 4, 5). In addition to the anticoagulant effects, ATIII exerts anti-inflammatory properties, including inhibition of nuclear factor κB activation in human monocytes and vascular endothelial cells (6), reduction of leukocyte-endothelial interactions (7), and prevention of microvascular leakage (8–12). ATIII may also compete with bacterial toxins for binding on endothelial cell proteoglycans (13), thereby reducing the inflammatory response after bacterial challenge (14). Interestingly, plasma-derived ATIII has been found to inhibit bacterial outgrowth and limited the inflammatory response, neutrophil influx, and histopathological changes in Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia (15), although it was unclear whether these beneficial effects were due to prostacyclin formation, interference with bacterial toxins such as pneumolysin, or reduced coagulation and related modulation of extracellular proteins and peptides. Due to its therapeutical potential in inflammation and coagulation, ATIII has been evaluated in clinical investigations targeting sepsis (1, 3, 14–18) but not found to significantly affect mortality in patients with sepsis in a larger phase III clinical trial (19).

Inhibition of thrombin by ATIII increases dramatically in the presence of heparin and involves specific and complex allosteric mechanisms based on minute conformational changes leading to an increased affinity for the negatively charged polysaccharide (9, 20–22). As such, ATIII displays similar features as HCII, a related serpin recently shown to exert antibacterial effects in vitro and in vivo (23). Hence, proteolytic cleavage of HCII induced a conformational change, thereby inducing endotoxin-binding and antimicrobial properties. Analyses employing representative peptide epitopes mapped these effects to helices A and D. Mice deficient in HCII showed increased susceptibility to invasive infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Thus protease-induced uncovering of cryptic epitopes by scission of the N-terminal anionic region in HCII transforms the molecule into a host defense factor. Similar to HCII, the region comprising helix D in ATIII constitutes a major heparin binding site (24). Notable are also the findings that ATIII may be degraded by neutrophil S. aureus V8 protease in vitro, generating heparin-binding peptides derived from the d-helix of ATIII (5). Taken together, the relatedness to HCII, the observation that ATIII contains a heparin-binding region represented by helix D, the multifunctionality of ATIII, as well as the above-mentioned suppressive effects on pneumococcal infections, prompted us to investigate possible antimicrobial effects exerted by ATIII or peptides derived from its helix D.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

KTS43 kTSDQIHFFFAKLNCRLYRKANKSSKLVSANRLFGDKSLTFNET, FFF21 (FFFAKLNCRLYRKANKSSKLVS), AKL22 (AKLNCRLYRKANKSSKLVSANR), and LL-37 (LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES) were synthesized by Innovagen AB (Lund, Sweden). The purity (>95%) and molecular weight was confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS analysis (Voyager, Applied Biosystems).

Microorganisms

Bacterial isolates E. coli ATCC 25922, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, P. aeruginosa Xen41 (PerkinElmer), Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, Candida albicans ATCC 90028, and Candida parapsilosis ATCC 90018 were obtained from the Department of Bacteriology (Lund University Hospital). P. aeruginosa 15159 was a clinical isolate derived from a patient with a chronic venous leg ulcer.

Radial Diffusion Assay

Bacteria were grown to mid-logarithmic phase in 10 ml of full-strength (3% w/v) trypticase soy broth (TSB) (BD Biosciences). The microorganisms were then washed once with 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4. Subsequently, 4 × 106 bacterial colony-forming units (cfu) were added to 15 ml of the underlay agarose gel, consisting of 0.03% (w/v) TSB, 1% (w/v) low electroendosmosis type agarose (Sigma) and 0.02% (v/v) Tween 20 (Sigma) with or without 0.15 m NaCl. The underlay was poured into a diameter 144-mm Petri dish. After agarose solidification, 4-mm diameter wells were punched, and 6 μl of test sample was added to each well. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h to allow diffusion of the peptides. The underlay gel was then covered with 15 ml of molten overlay (6% TSB and 1% low electroendosmosis type agarose in distilled H2O). Antimicrobial activity of a peptide is visualized as a zone of clearing around each well after 18–24 h of incubation at 37 °C.

Viable Count Analysis

E. coli was grown to mid-exponential phase in Todd-Hewitt broth. Bacteria were washed and diluted in 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, containing 0.15 m NaCl, either alone or with 20% human citrate plasma. 2 × 106 cfu/ml bacteria were incubated in 50 μl, at 37 °C for 2 h with the ATIII-derived peptides KTS43, FFF21, and AKL22, as well as the control peptide LL-37, at the indicated concentrations. Serial dilutions of the incubation mixture were plated on Todd-Hewitt agar, followed by incubation at 37 °C overnight and cfu determination.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Sigma-Aldrich) was used for monitoring of bacterial membrane permeabilization. E. coli ATCC 25922 bacteria were grown to mid-logarithmic phase in TSB medium. Bacteria were washed and resuspended in buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl, and 5 mm glucose) to yield a suspension of 1 × 107 cfu/ml. One hundred μl of the bacterial suspension was incubated with 30 μm of the respective peptides at 30 °C for 30 min. Microorganisms were then immobilized on poly-l-lysine-coated glass slides by incubation for 45 min at 30 °C, followed by addition onto the slides of 200 μl of FITC (6 μg/ml) in buffer and a final incubation for 30 min at 30 °C. The slides were washed, and bacteria was fixed by incubation, first on ice for 15 min and then in room temperature for 45 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. The glass slides were subsequently mounted on slides using Prolong Gold antifade reagent mounting medium (Invitrogen). Bacteria were visualized using a Nikon Eclipse TE300 (Nikon) inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu C4742–95 cooled CCD camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ) and a Plan Apochromat ×100 objective (Olympus, Orangeburg, NY). Differential interference contrast (Nomarski) imaging was used for visualization of the microbes themselves.

Electron Microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy and visualization of peptide effects on bacteria, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 and S. aureus ATCC 29213 (1–2 × 106 cfu/sample) were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with the peptides (30 μm). Samples of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus suspensions were adsorbed onto carbon-coated copper grids for 2 min, washed briefly by two drops of water, and negatively stained by two drops of 0.75% uranyl formate. The grids were rendered hydrophilic by glow discharge at low pressure in air. All samples were examined with a Jeol JEM 1230 electron microscope operated at 80 kV accelerating voltage. Images were recorded with a Gatan Multiscan 791 charge-coupled device camera.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

ATIII, either intact or subjected to enzymes, was analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 16.5% Tris-tricine gels (Bio-Rad). For identification of ATIII fragments in patient samples, 1.5 μl of wound fluid was analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Proteins and peptides were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-C). Membranes were blocked by 3% (w/v) skimmed milk, washed, and incubated for 1 h with chicken anti-human ATIII polyclonal antibodies (1:1000) (Abcam), washed three times for 10 min, subsequently incubated (1 h) with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000) (Dako), and then washed again three times, each time for 10 min. ATIII and related fragments were visualized using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate developing system (Thermo Scientific).

Slot-blot Assay

LPS-binding ability of the peptides was examined by a slot-blot assay. Peptides (1, 2, and 5 μg) were bound to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-C, GE Healthcare), which were presoaked in PBS. Membranes were then blocked by 2 WT% BSA in PBS, pH 7.4, for 1 h at room temperature, and subsequently incubated with 125I-labeled LPS (40 μg/ml; 0.13 × 106 cpm/μg) for 1 h in PBS. After incubation, the membranes were washed three times, 10 min each time, in PBS and visualized for radioactivity using a Bas 2000 radioimaging system (Fuji). Unlabeled heparin (6 mg/ml) was added for competition of binding.

Degradation of Antithrombin III

Antithrombin III (Innovative Research) or heparin cofactor II (Hematologic Technologies, Inc.) (27 μg) was incubated with human leukocyte elastase (HLE) (0.6 μg, 20 units/mg) (Calbiochem®) in a total volume of 50 μl of PBS and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min or 18 h. In another experiment, antithrombin III (20 μg) was incubated at 37 °C overnight with S. aureus V8 protease (V8 concentrations as indicated in Fig. 1B) or with HLE (10 μg, 20 units/mg) in a total volume of 50 μl of PBS. The reaction was stopped by boiling at 95 °C for 3 min. The fragmentation pattern was analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 16.5% precast Tris-tricine gels (Bio-Rad), run under reducing conditions. The gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue and destained according to routine procedures.

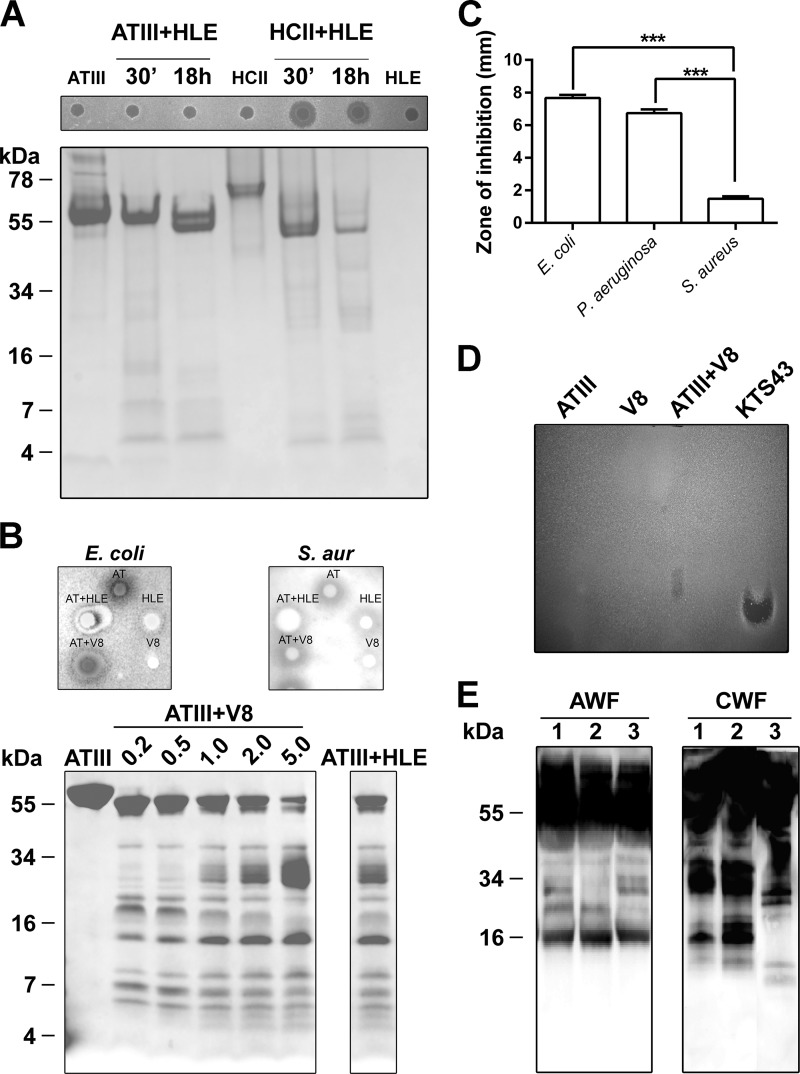

FIGURE 1.

Proteolytic cleavage of ATIII by human leukocyte elastase and S. aureus V8 proteases. A, analysis of the two serpins ATIII and HCII by SDS-PAGE after incubation with HLE (27 μg of HCII or ATIII, 0.6 μg of HLE). Protein digestion was performed at 37 °C for 30 min or 18 h and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (16.5% Tris-Tricine gels) (lower panel). The antimicrobial activity was tested against E. coli using RDA assay (upper panel). Molecular weight markers are indicated. B, twenty μg of ATIII was digested with V8 protease at the indicated concentrations (0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 μg) sfor 24 h at 37 °C, and samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie. The right panel shows ATIII digested with excessive dose of HLE (10 μg). The antimicrobial activity was tested against E. coli and S. aureus using RDA assay (upper panel, V8, 5 μg; HLE, 10 μg). C, RDA analysis of KTS43. For determination of antibacterial activity of KTS43, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus (S. aur; 4 × 106 cfu) (indicated on the x axis) were inoculated in 0.1% TSB agarose gels in 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4. Each 4-mm-diameter well was loaded with 6 μl of peptide (100 μm). The zones of clearance (y axis) correspond to the inhibitory effect of each peptide after incubation at 37 °C for 18–24 h (mean values are presented, n = 3). ***, p < 0.0002. D, ATIII digested with V8 was analyzed for antimicrobial activity by gel overlay assay. KTS43 (2 μg) was used for positive control. V8 and ATIII were run alone separately. E, degradation of ATIII in human wounds. Acute wound fluid (patients 1–3, AWF), or wound fluid from patients with chronic ulcers (patients 1–3, CWF) were analyzed by Western blot using polyclonal antibodies against ATIII.

NF-κB Activation Assay

The NF-κB reporter cell line THP1-XBlue-CD14 (InvivoGen) was cultured according to manufacturer's instructions. THP1-XBlue-CD14 cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml E. coli LPS (0111:B4) together with the indicated concentrations of KTS43, FFF21, and LL-37 for 20–24 h. Measurement of NF-κB/AP-1 activation was done using the Quanti Blue assay according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, upon stimulation, the cell line produces secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase, detected in cell supernatants by using a secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase detection reagent followed by analysis of the absorbance at 600 nm. The toxicity was assed using the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazoliumbromide (MTT) assays described below (see LDH and MTT assay, respectively).

Animal Infection Models

Animal experiments were performed according to a protocol approved by the Local Ethics Committee at Lund University. Animals were housed under standard conditions of light and temperature and had free access to standard laboratory chow and water. For experiments evaluating bacterial and platelet levels during infection (see Fig. 7, C and D), P. aeruginosa 15159 bacteria were grown to mid-exponential phase (A620 ∼ 0.5), harvested, washed in PBS, diluted in the same buffer to 2 × 108 cfu/ml, and kept on ice until injection. One hundred microliter of the bacterial suspension was injected intraperitoneally (intraperitoneal) into male C57BL/6 mice. Immediately after bacterial injection, 0.5 mg of FFF21 peptide or buffer alone was administrated intraperitoneal Data from three independent experiments were pooled. For experiments assessing animal survival and bacterial spread by in vivo imaging (see Fig. 7, E–G), P. aeruginosa Xen41 bacteria were grown to mid-exponential phase (A620 ∼ 0.5), harvested, washed in PBS, diluted in the same buffer to 2 × 107 cfu/ml, and kept on ice until injection. One hundred microliter of the bacterial suspension was injected intraperitoneally (intraperitoneal) into male BALB/c mice. Thirty min and 2 h after bacterial injection, 0.5 mg of FFF21 peptide or buffer alone was administrated intraperitoneal data from two independent experiments were pooled. 0 and 10 h after bacterial infection, mice were anesthetized, followed by data acquisition and analysis using a Spectrum three-dimensional imaging system with Living Image® (version 4.4, Caliper Life Sciences). For evaluation of animal survival, mice showing the defined and approved end point criteria (immobilization and shaking) were sacrificed by an overdose of isoflurane (Abott) and counted as non-survivors.

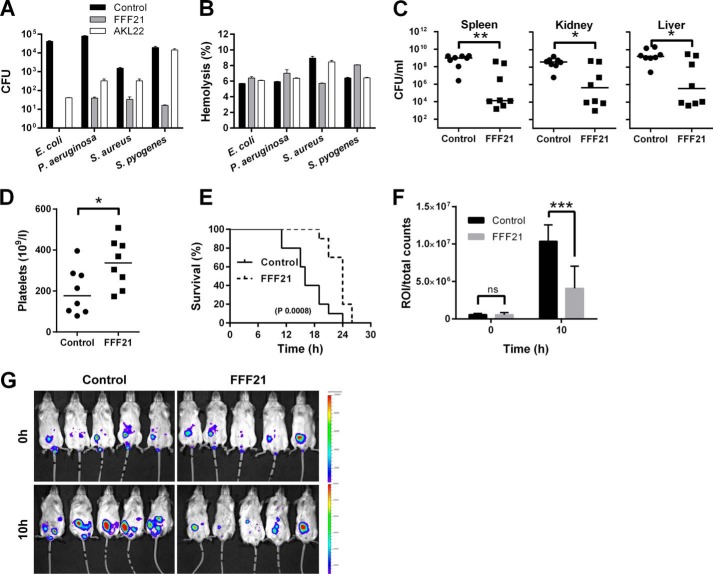

FIGURE 7.

Peptide activity in human blood infected by bacteria and in an animal model of P. aeruginosa sepsis. The indicated Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial strains (2 × 108 cfu/ml) were added to 50% citrate blood (diluted in PBS), followed by addition of peptide at 60 μm. A, antibacterial effects (after 1 h) of the indicated peptides were determined. The number of bacteria was analyzed (y axis). B, using the same material, hemolysis in human blood in presence of the indicated bacteria as well as peptides was analyzed. Hemolysis was assessed after 1 h. 1% Triton X-100 was used as positive control (yielding 100% permeabilization). C, effects of FFF21 in mice infected by P. aeruginosa 15159. FFF21 suppresses bacterial dissemination to the spleen, liver and kidney. C57BL6 mice were injected intraperitoneal with P. aeruginosa bacteria, followed by intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 mg of FFF21 or buffer only, and the cfu of P. aeruginosa in spleen, liver, and kidney was determined after a time period of 12 h (n = 8 for controls and treated, p < 0.05 for spleen, liver, and kidney. Horizontal line indicates median value). D, platelet counts were analyzed in blood from the same experiments. E, in a separate experiment, mice were challenged with 2 × 107 cfu/ml P. aeruginosa Xen41 (intraperitoneal) and FFF21 (0.5 mg) was administered intraperitoneal 30 min and 2 after injection of bacteria (n = 5 in each group). F, bioluminescence signal of whole individual mice was measured using the regions of interest (ROI) total count analysis at 0 and 10 h after bacterial injection. G, mice were imaged immediately after bacterial challenge and 10 h after post-infection.

Hemolysis Assay

EDTA blood was centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 min, where plasma and buffy coat were removed. Erythrocytes were washed three times and resuspended in PBS, pH 7.4, to a 5% suspension. The cells were then incubated with end-over-end rotation for 60 min at 37 °C in the presence of peptides at the indicated concentrations. 2% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) served as positive control. The samples were then centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a 96 well microtiter plate. The absorbance of hemoglobin release was measured at 540 nm and expressed as % of Triton X-100-induced hemolysis. In another experiment, citrate blood was diluted (1:1) with PBS, whereafter 2 × 108 cfu/ml bacteria were added, and the mixture incubated with end-over-end rotation for 1 h at 37 °C in the presence of peptides (60 and 120 μm). For evaluation of hemolysis, samples were then processed as above. Results given represent mean values from triplicate measurements.

LDH Assay

HaCaT keratinocytes (kindly provided by Professor Fusenig) were grown to confluency in 96-well plates (3000 cells/well) in serum-free keratinocyte medium (SFM) supplemented with bovine pituitary extract and recombinant EGF (BPE-rEGF) (Invitrogen). The medium was then removed, and 100 μl of the peptides was investigated (at 3, 6, 30, and 60 μm, diluted in SFM/BPE-rEGF or in keratinocyte-SFM supplemented with 20% human serum) were added. The LDH-based TOX-7 kit (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for quantification of LDH release from the cells. Results represent mean values from triplicate measurements and are given as fractional LDH release compared with the positive control consisting of 1% Triton X-100 (yielding 100% LDH release).

MTT Assay

Sterile filtered MTT (Sigma-Aldrich) solution (5 mg/ml in PBS) was stored protected from light at −20 °C until usage. HaCaT keratinocytes, 3000 cells/well, were seeded in 96-well plates and grown in keratinocyte-SFM/BPE-rEGF medium to confluence. Keratinocyte-SFM/BPE-rEGF medium alone, or keratinocyte-SFM supplemented with 20% serum, was added and followed by peptide addition (3, 6, 30, and 60 μm). After incubation overnight, 20 μl of the MTT solution was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 1 h in CO2 at 37 °C. The MTT-containing medium was then removed by aspiration. The blue formazan product generated was dissolved by the addition of 100 μl of 100% dimethyl sulfoxide per well. The plates were then gently swirled for 10 min at room temperature to dissolve the precipitate. The absorbance was monitored at 550 nm, and results given represent mean values from triplicate measurements.

Liposome Preparation and Leakage Assay

The liposomes investigated were anionic (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol/1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol, monosodium salt, 75/25 mol/mol). 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol, monosodium salt and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phoshoetanolamine were both from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster) and of >99% purity. Due to the long, symmetric, and unsaturated acyl chains of these phospholipids, several methodological advantages are reached. In particular, membrane cohesion is good, which facilitates very stable, unilamellar, and largely defect-free liposomes, allowing detailed studies on liposome leakage. The lipid mixtures were dissolved in chloroform, after which solvent was removed by evaporation under vacuum overnight. Subsequently, 10 mm Tris buffer, pH 7.4, was added together with 0.1 m carboxyfluorescein (Sigma). After hydration, the lipid mixture was subjected to eight freeze-thaw cycles consisting of freezing in liquid nitrogen and heating to 60 °C. Unilamellar liposomes of diameter ∼140 nm were generated by multiple extrusions through polycarbonate filters (pore size of 100 nm) mounted in a LipoFast miniextruder (Avestin, Ottawa, Canada) at 22 °C. Untrapped carboxyfluorescein was removed by two subsequent gel filtrations (Sephadex G-50, GE Healthcare) at 22 °C, with Tris buffer as eluent. Carboxyfluorescein release from the liposomes was determined by monitoring the emitted fluorescence at 520 nm from a liposome dispersion (10 μm lipid in 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4). An absolute leakage scale was obtained by disrupting the liposomes at the end of each experiment through addition of 0.8 mm Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). A SPEX-fluorolog 1650 0.22-m double spectrometer (SPEX Industries, Edison, NJ) was used for the liposome leakage assay. Measurements were performed in triplicate at 37 °C.

CD Spectroscopy

CD spectra of the peptides were measured on a Jasco J-810 Spectropolarimeter (Jasco). The measurements were performed at 37 °C in a 10-mm quartz cuvette under stirring, and the peptide concentration was 10 μm. The effect on peptide secondary structure of liposomes at a lipid concentration of 100 μm was monitored in the range of 200–260 nm. The fraction of the peptide in α-helical conformation, Xα, was calculated as described previously (25, 26). For determination of effects of lipopolysaccharide on peptide structure, the peptide secondary structure was monitored at a peptide concentration of 10 μm, both in Tris buffer and in the presence of E. coli lipopolysaccharide (0.02 WT%) (E. coli 0111:B4, highly purified, <1% protein/RNA, Sigma). Background subtractions were performed routinely. Signals from the bulk solution were also corrected.

Statistical Analysis

Bar diagrams (radial diffusion assays (RDA) and viable count assay (VCA)) are presented as mean and S.D., from at least three independent experiments. Animal data are presented as dot plots, with mean for normally distributed data or median for data, which do not meet the criteria for normal distribution. Outliers were not excluded from the statistical analysis. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Degradation of ATIII and Comparison with HCII

Previous results showed that HLE yielded a fast and selective degradation of HCII, releasing a highly anionic N-terminal peptide, and resulting in generation of an antimicrobial HCII form (23). Thus, ATIII and HCII were digested with HLE (23) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A, lower panel) and probed for antibacterial effects using radial diffusion assay (Fig. 1A, upper panel). Whereas HCII, subjected to HLE, displayed an effect in RDA, no such activity was observed for ATIII. Likewise, intact ATIII did not exert any antimicrobial effects in viable count assays (data not shown). We next evaluated whether more extensive proteolysis of ATIII, previously demonstrated to generate low molecular weight fragments encompassing an epitope of helix D (5) could uncover cryptic antimicrobial activity. ATIII was digested with increasing concentrations of V8 protease and also with a significantly higher dose of HLE. In both cases, and unlike the results in Fig. 1A, SDS-PAGE analysis now showed low molecular weight ATIII fragments (Fig. 1B, lower panel). RDA analyses of fractions showed that these digested ATIII fractions were antimicrobial, although it was noted that the V8-digested material displayed activity against E. coli, whereas S. aureus was not inhibited (Fig. 1B, upper panels). It was also noted that the excessive dose of HLE was antimicrobial against E. coli alone, although the zone was smaller than observed for the combination (ATIII+HLE) (Fig. 1B, upper panel). We next reasoned that the helix d-derived fragment of ATIII, described previously to be released by V8 protease (4, 5), could contribute to the observed antimicrobial effects. Indeed, in RDA assays, the synthesized 43-amino acid peptide encompassing helix D, KTS43, showed antimicrobial effects particularly against E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Fig. 1C). The peptide was significantly less active against S. aureus, corresponding to the results obtained with digested ATIII above (Fig. 1B). To further evaluate whether digested ATIII may give rise to such antimicrobial fragments upon proteolysis, a gel overlay assay was employed. The peptide KTS43 was used for positive control and comparison of migration. As expected, KTS43 yielded a single antimicrobial zone (Fig. 1D). The results also showed that one major antimicrobial product, migrating similar to KTS43, was formed after subjecting ATIII to V8 protease (Fig. 1D). The minor migration difference could be due to presence of alternative truncated variants and/or presence of glycosylations in the native human ATIII preparation. Of relevance is that the KTS43 fragment contains the sequence NKS, where Asn-135 has been shown to be glycosylated (27). Taken together, the results thus showed that considerably higher HLE levels were required for generation of antimicrobial activity from ATIII when compared with HCII and that a helix D derived peptide mediates this activity. Finally, by using Western blotting and ATIII polyclonal antibodies, presence of possible ATIII fragmentation was explored in wound fluid from patients post-surgery, as well as in fluids from patients with chronic (S. aureus-infected) venous leg ulcers, the latter characterized by high proteolytic activity (28). As shown in Fig. 1E, several low molecular weight fragments were identified in those patient samples, particularly in the fluids from chronic ulcers.

Antimicrobial Activities of Helix d-derived ATIII Peptides

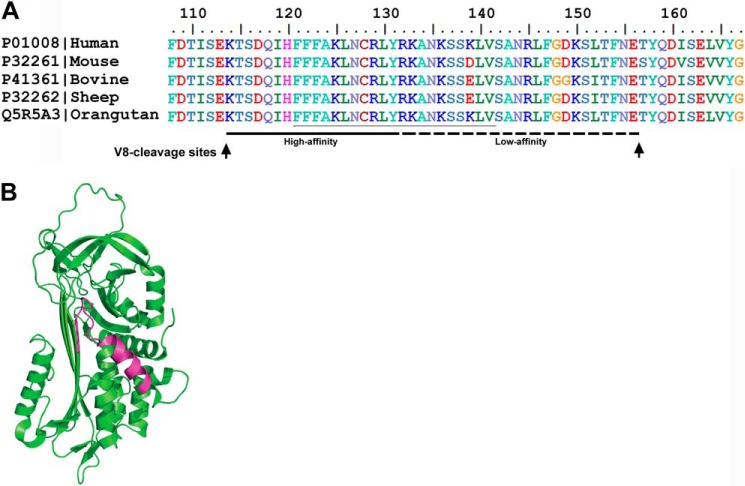

Because S. aureus V8 protease generates a heparin-binding peptide comprising helix D (4, 5) with antimicrobial activity, we next decided to select prototypic peptides of this region for further analyses. The selection of peptides from helix D was based on previous reports on the contribution of particularly the central cationic amino acids of helix D to the observed interactions with heparin (29). As noted, these residues also display a high degree of conservation among species (Fig. 2A). Taking this into account, the peptides FFF21 (FFFAKLNCRLYRKANKSSKLVS) as well as a previously reported region found to bind heparin, AKL22 (AKLNCRLYRKANKSSKLVSANR) (29), were selected and synthesized. The peptide FFF21 is color marked in the three-dimensional structure of human ATIII (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Illustration of the helix D region of ATIII. A, sequence homology. Sequence homologies of the helix D region of ATIII of different species are shown. Regions critical for heparin binding activity (high and low affinity) and S. aureus V8 protease cleavage sites (arrows) are indicated in the figure. B, schematic representation of ATIII structure (Protein Data Bank code 2B4X). Sequence of the heparin binding peptide FFF21 is indicated.

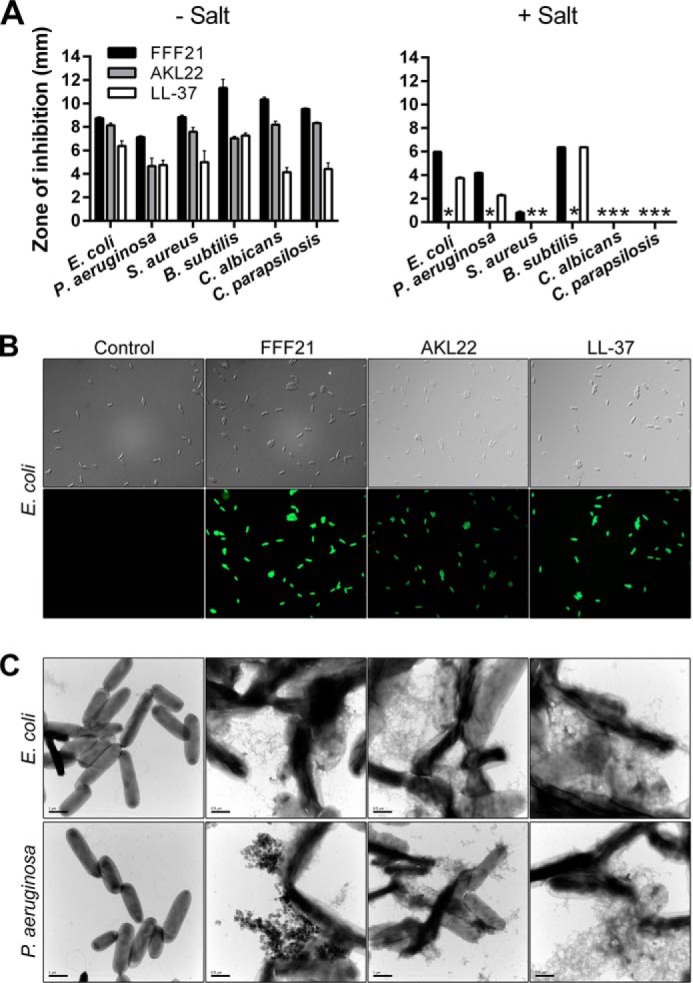

We next investigated the effects of the peptides FFF21 and AKL22 on bacteria. As shown in Fig. 3A, both peptides were antibacterial in RDA using the Gram-negative bacteria E. coli and P. aeruginosa and the Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus, B. subtilis, and the fungi C. albicans and C. parapsilosis. Note that FFF21 yielded similar or larger inhibition zones when compared with the benchmark antimicrobial peptides LL-37 in the presence of 0.15 m NaCl (Fig. 3A, right panel). Also of note was that the two peptides showed no or little activity in presence of salt against S. aureus, relative the effects on E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Fig. 3A, right panel).

FIGURE 3.

Antibacterial activities and peptide-mediated bacterial permeabilization. A, for determination of antibacterial activities, the indicated bacterial or fungal isolates (4 × 106 cfu) (indicated on the x axis) were inoculated in 0.1% TSB agarose gels in 10 mm Tris, pH 7.4, only or with 0.15 m NaCl. Each 4-mm-diameter well was loaded with 6 μl of peptide (at 100 μm). The zones of clearance (y axis) correspond to the inhibitory effect of each peptide after incubation at 37 °C for 18–24 h (mean values are presented, n = 3). B, permeabilizing effects of peptides on E. coli. Bacteria were incubated with the indicated peptides, and permeabilization was assessed using the impermeant probe FITC. C, electron microscopy analysis. E. coli and P. aeruginosa and bacteria were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with 30 μm of the ATIII-derived peptides and analyzed by electron microscopy. Results with LL-37 are also included for comparison. Scale bar represents 1 μm.

Permeabilization and Electron Microscopy Studies

Fig. 3B shows that the ATIII-derived peptides permeabilized E. coli cells, as visualized with the impermeant probe FITC. To further examine peptide-induced permeabilization of bacterial plasma membranes, E. coli and P. aeruginosa were incubated with the peptides at a concentration yielding complete bacterial killing (30 μm) and analyzed by electron microscopy (Fig. 3C). Clear differences in morphology between peptide-treated bacteria and the control were demonstrated. Similarly to LL-37, the ATIII-derived peptides caused local perturbations and breaks along E. coli and P. aeruginosa membranes, and intracellular material was found extracellularly.

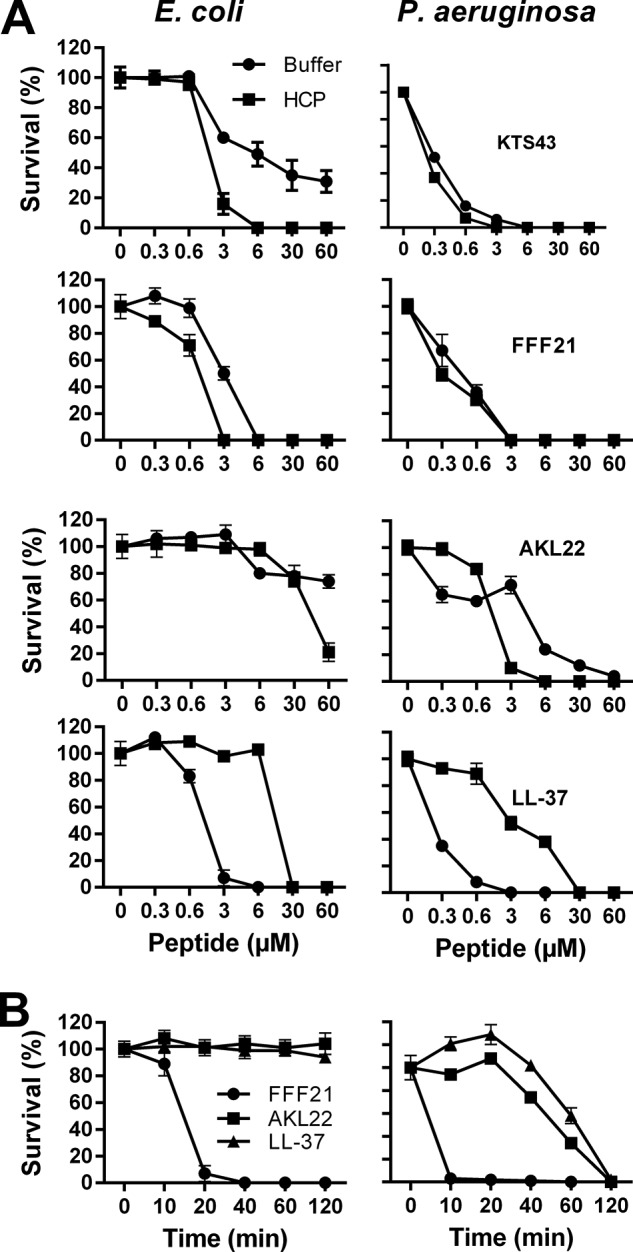

Peptide Effects at Physiological Conditions

Activities of AMP depend on salt concentration, pH, and the presence of plasma proteins. For example, the antimicrobial activities of defensins are inhibited by the presence of physiological salt (30), whereas the cathelicidin LL-37 is partly inhibited by plasma (31). Hence, we examined the peptide activities in presence of human plasma proteins and in physiological salt conditions. The results from these viable count experiments showed that particularly the original fragment KTS43 and its truncated form FFF21 (see Fig. 2) retained its antibacterial activity in presence of plasma proteins at physiological salt conditions (Fig. 4A). It is notable that compared with FFF21, an ∼10 times higher concentration (≈30 μm) of LL-37 was required for efficient killing. In addition, kinetic studies in the presence of plasma and using 6 μm of each peptide demonstrated that the killing of E. coli mediated by FFF21 occurred within 20–40 min, indicating a fast direct action compatible with many antimicrobial peptides (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Antibacterial activities of ATIII-derived peptides at physiological concentrations. A, antibacterial effects of the peptides KTS43, FFF21, AKL22, and LL-37 were analyzed against E. coli and P. aeruginosa in viable count assays. 2 × 106 cfu/ml bacteria were incubated in 50 μl with peptides at the indicated concentrations in 10 mm Tris, 0.15 m NaCl, pH 7.4 (buffer), or in 10 mm Tris, 0.15 m NaCl, pH 7.4, containing 20% human citrate plasma (HCP) (n = 3, S.D. is indicated). B, peptide kinetics. E. coli and P. aeruginosa bacteria were subjected to the indicated peptides (at 6 μm) in 10 mm Tris, 0.15 m NaCl, pH 7.4, containing 20% human citrate plasma and incubated at 37 °C for 0, 10, 20, 40, 60, and 120 min. LL-37 data are shown for comparison.

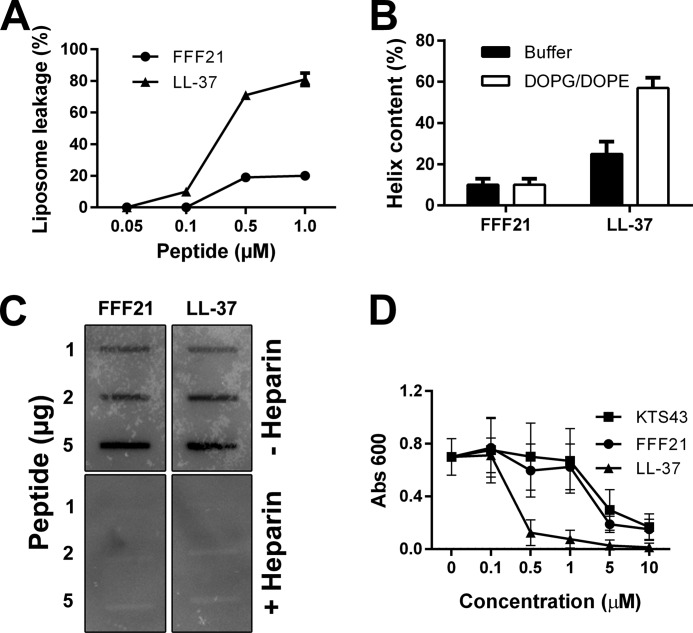

Liposome Interactions and CD Analysis

FFF21 showed a modest increase in liposome leakage (Fig. 5A) and no significant helix induction upon incubation with model anionic liposomes (Fig. 5B). As demonstrated by a slot-binding assay, the peptide FFF21 bound to iodinated LPS at physiological salt (0.15 m NaCl), which was completely blocked by an excess of heparin (Fig. 5C). Compatible with previous reports on heparin-binding (29), FFF21 also bound to iodinated heparin in a similar slot-blot experiment (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Liposome effects, LPS-binding, and anti-endotoxin activity of FFF21. A, effects of FFF21 on liposome leakage. The membrane-permeabilizing effect was recorded by measuring fluorescence release of carboxyfluorescein from 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phoshoetanolamine/1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol, monosodium salt (DOPE/DOPG) (negatively charged) liposomes. The experiments were performed in 10 mm Tris buffer. Values represents mean of triplicate samples. B, helical content of FFF21 peptide in presence of negatively charged liposomes (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phoshoetanolamine/1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol, monosodium salt). C, LPS-binding activities of peptides. 1, 2, and 5 μg of the indicated peptides were applied onto nitrocellulose membranes, followed by incubation with iodinated [125I]LPS in PBS (containing 3% BSA). Unlabeled heparin (6 mg/ml) was added for competition of binding. LL-37 is included for comparison. D, anti-endotoxic effects in a monocyte model. Dose-dependent inhibitory effects on THP1-XBlue-CD14 stimulated by LPS are evaluated. Cells were stimulated with E. coli LPS (10 ng/ml), with and without addition of KTS43, FFF21, or LL-37 at 0.1–10 μm. LPS-stimulated cells without peptide were used as control.

Anti-endotoxic Effects of FFF21 and KTS43

As mentioned previously, intact ATIII did not exert antimicrobial effects in an RDA assay, and it was not active against bacteria in viable count assays. Considering previous reports that ATIII may exert anti-endotoxic effects (32, 33), we explored the effects of FFF21 with respect to effects on effects on LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells. FFF21 was able to block the response to LPS at doses corresponding to the physiological concentration of ATIII (∼5 μm). Interestingly, the original KTS43 peptide exerted almost identical anti-endotoxic effects (Fig. 5D).

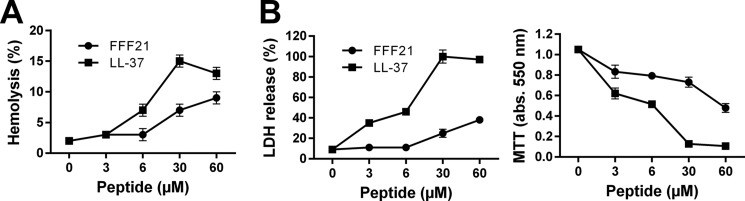

Effects on Human Cells

As a prelude to subsequent in vivo evaluations using the prototypic FFF21 peptide, we wanted to determine potential permeabilizing effects of the peptides on eukaryotic membranes. A low hemolytic activity was noted for the FFF21 peptide at doses yielding complete bacterial killing (3–6) μm (Fig. 6A). This contrasted to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37, which permeabilized erythrocytes at doses >6 μm. Analogously, the peptide showed significantly less activity against human epithelial cells (HaCaT keratinocyte cell line) than the benchmark peptide LL-37, as judged by LDH release and viability (Fig. 6B). Neither FFF21 nor KTS43 did exert any toxic effects on THP-1 cells at concentrations exceeding those exerting anti-endotoxic effects (compare with Fig. 5D).

FIGURE 6.

Membrane activity. A, hemolytic effects. Data for the peptide FFF21 are presented, and corresponding data for LL-37 included for comparison. The cells were incubated with the peptide at the indicated concentrations. The absorbance of hemoglobin release was measured at 540 nm and is expressed as % of Triton X-100 induced hemolysis (note scale of y axis). 2% Triton X-100 served as a positive control. B, Effects of peptides on HaCaT cells. Cell permeabilizing effects of the indicated peptides (upper panel) were measured by the LDH-based TOX-7 kit. LDH release from the cells was measured at 490 nm and was plotted as % of total LDH release. The MTT assay (right panel) was used to measure viability of HaCaT keratinocytes. In the assay, MTT is modified into a dye, blue formazan, by enzymes associated with metabolic activity. The absorbance (abs.) of the dye was measured at 550 nm.

Peptide Activities in Blood Infected by Bacteria

To simultaneously explore antimicrobial (Fig. 7A) and hemolytic effects (Fig. 7B), the two prototypic peptides FFF21 and AKL22 were added to human blood infected by E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, or Streptococcus pyogenes. Compatible with previous results, it was observed that FFF21 was particularly efficient against Gram-negative bacteria. Furthermore, the peptide displayed a significant selectivity, demonstrating almost complete eradication of E. coli and P. aeruginosa, with little (∼ 5% or less) accompanying hemolysis (Fig. 7B), at a peptide dose of 60 μm. Taken together, the combination of hemolysis results and permeabilization studies on HaCaT keratinocytes indicate that FFF21 show low toxicity at doses above those needed for antimicrobial effects.

Effects of FFF21 during Pseudomonas aeruginosa Sepsis

To further investigate the effects of FFF21 in vivo, we injected this peptide into mice infected intraperitoneally with P. aeruginosa. As shown in Fig. 7C, treatment with FFF21 given immediately after infection significantly reduced bacterial numbers in the spleen, liver, and kidney of the animals. Analyses of blood platelet counts after 12 h showed increased platelet levels in FFF21-treated mice, an indication of reduced consumption during infection (Fig. 7D). The results thus demonstrate an antibacterial effect of FFF21 in vivo during experimental infection. Finally, in a separate experiment, FFF21 was given 30 min and 2 h after bacterial infections and survival, as well as bacterial spread was analyzed using bioimaging. The results showed that this two-dose regimen resulted in prolonged survival (Fig. 7E), and bacterial spread was counteracted by the peptide (Fig. 7, F and G).

DISCUSSION

The major finding in the present study is the identification of an antibacterial and anti-endotoxic activity of a peptide region comprising helix D in human ATIII. This further substantiates the concepts presented in previous studies (34–41), showing that various endogenous proteins harbor cryptic epitopes that display antimicrobial and in some cases other bioactive effects. Major questions of importance are to what extent the observed activities for such helix D peptides may be applied to the ATIII holoprotein and whether specific proteolysis, releasing helix D fragments, is required for some ATIII functions.

Considering the antimicrobial activity, it was shown that nebulized ATIII limits bacterial outgrowth and lung injury in Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia in rats (42). In relation to this, however, the authors did not detect any direct antimicrobial effects of ATIII against pneumococci, and it was therefore concluded that the inhibitory effects of ATIII on bacteria must be indirect. In this work, we did not observe any antimicrobial effects of intact ATIII under various conditions, e.g. using low salt conditions permissive for facilitating bacterial killing or plasma for detection of possible synergistic effects of ATIII and plasma proteins, including complement. Hence, the data indicate that intact ATIII, under the experimental conditions used here, does not kill bacteria per se. Nevertheless, the possibility that the molecule acts directly on bacteria in particular environments cannot be excluded. Bacteria, such as S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, frequently colonize and infect skin wounds, accompanied by excessive proteolysis and activation of neutrophils (28, 43). During wounding and infection, local release of proteases such as neutrophil elastase or bacterial proteinases is typically widespread. Conceptually, it is thus possible that proteolysis of ATIII may generate antimicrobial fragments, and compatible with this are the observation that S. aureus V8 protease generates a major fragment Lys-147–Glu-189 (KTS43), which perfectly encompasses the exposed heparin binding helix D in the ATIII molecule (5), corresponding to antimicrobial FFF21. At first glance, it may appear counterproductive, from a microbial perspective, that a staphylococcal protease generates antimicrobial peptides. However, the finding that S. aureus was relatively resistant to the effects of both KTS43 and FFF21 suggests that these peptides likely do not play a role in host defense against this pathogen in vivo. Hypothetically, other effects of S. aureus V8 protease, such as induction of an anti-inflammatory response by KTS43 and related fragments, deactivation of the antithrombotic effects of ATIII, or perhaps generation of peptides controlling competing Gram-negative bacteria, may be more relevant from an evolutionary perspective.

Although it is not antimicrobial on its own, ATIII has been reported to display immunomodulatory activities, involving thrombin-independent effects on various cell types. Thus, ATIII affects B- and T-cell activation, reduces neutrophil migration, and inhibits endotoxin-induced production of tissue factor by mononuclear cells (32). The molecular basis of these direct cellular effects has not been elucidated. Because previous data shows that ATIII exerts anti-inflammatory effects (11), our results on LPS-binding and anti-endotoxic activity of FFF21 suggest that the d-helix region may contribute to the anti-inflammatory capacity of intact ATIII. However, it is notable that the inhibitory effects noted by Souter et al. (11) required 20 times the physiological dose of ATIII. Because we here observed that the FFF21 peptide was anti-inflammatory at 20 times lower concentrations in our macrophage models, this again underlines that fragmentation may add new functionalities to ATIII with respect to anti-inflammatory activity. In this context, it is interesting to note that in a recent clinical phase III study on patients with severe sepsis, a possible survival benefit was observed only in those patients not receiving concomitant heparin (19, 32), suggesting the possibility of heparin-mediated blocking of helix d-mediated functions in vivo, compatible with the observed anti-endotoxic (and also antimicrobial) effects of helix D peptides in vitro. Thus, given the above, it is possible that ATIII therapy in sepsis should be limited to patients not on heparin treatment and perhaps also to those with suspected Gram-negative infection.

From a structural perspective, the prototypic peptide FFF21 shares many characteristics with classical helical antimicrobial peptides such as amphipathicity and high net positive charge. Furthermore, end-tagging with short Trp and Phe amino acid stretches have been found to facilitate membrane binding, also at high ionic strength and in the presence of serum, as well as efficient membrane lysis and antimicrobial properties (44–46). For Trp- and Phe-tagged AMPs, the end-tagging furthermore contributes to selectivity between bacteria/fungi and mammalian cells (47). The latter is due to both charge density differences between these membranes, and due to the bulkiness of the Trp/Phe residues, which result in a large free energy penalty on membrane incorporation, particularly in the presence of membrane-condensing cholesterol, as in mammalian cells. In this context, it is notable that the peptide FFF21 also contains such a hydrophobic “F-tag” at its N-terminal end, leading to increased hydrophobicity and, consequently, interactions with particularly bacterial membranes.

From a therapeutic perspective, due to the increasing resistance problems against conventional antibiotics, antimicrobial and immunomodulatory peptides have recently gained much interest due to their capacity to selectively boost or down-regulate immune effectors during infection (44–46, 48–50). Naturally occurring peptide epitopes may show promise in a therapeutic setting considering low immunogenicity paired with the endogenous immunomodulatory activities described here. Considering the endotoxin-neutralizing activities, the mode of action FFF21 may involve binding to and neutralization of LPS, yielding inhibition of subsequent TLR-signaling, as described for other helical peptides (51). However, it is also possible that the peptide acts by additional mechanisms, which involve direct effects on host cells such as macrophages.

In summary, we here define peptides derived from helix D of ATIII mediating antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities. A selected peptide showed low toxicity, and reduced bacterial levels in a P. aeruginosa sepsis model. Further studies are warranted to define the structure-function relationships of this peptide region in intact ATIII, as well as the release of related helix D fragments in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lotta Wahlberg and Ann-Charlotte Strömdahl for expert technical assistance and Björn Walse (Saromics AB, Lund) for the illustration of the structure of ATIII.

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (Projects 2012-1842 and 2012-1883), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Welander-Finsen, Torsten Söderberg, Thelma-Zoegas, Crafoord, Alfred Österlund, and Kock Foundations, and The Swedish Government Funds for Clinical Research. Drs. Schmidtchen and Malmsten have shares in XImmune AB, a company involved in the therapeutic development of peptides for systemic use.

- ATIII

- antithrombin III

- HCII

- heparin cofactor II

- TSB

- trypticase soy broth

- HLE

- human leukocyte elastase

- LDH

- lactate dehydrogenase

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazoliumbromide

- SFM

- serum-free keratinocyte medium

- BPE-rEGF

- bovine pituitary extract and recombinant EGF

- RDA

- radial diffusion assay.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fourrier F. (1998) Therapeutic applications of antithrombin concentrates in systemic inflammatory disorders. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 9, S39–S45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fourrier F., Chopin C., Goudemand J., Hendrycx S., Caron C., Rime A., Marey A., Lestavel P. (1992) Septic shock, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation: compared patterns of antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S deficiencies. Chest 101, 816–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ostermann H. (2002) Antithrombin III in Sepsis: new evidences and open questions. Minerva Anestesiol. 68, 445–448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith J. W., Knauer D. J. (1987) A heparin binding site in antithrombin III: identification, purification, and amino acid sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 11964–11972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu C. S., Chang J. Y. (1987) Probing the heparin-binding domain of human antithrombin III with V8 protease. Eur. J. Biochem. 167, 247–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oehlschläger S., Albrecht S., Hakenberg O. W., Manseck A., Froehner M., Zimmermann T., Wirth M. P. (2002) Measurement of free radicals and NO by chemiluminescence to identify the reperfusion injury in renal transplantation. Luminescence 17, 130–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoffmann J. N., Vollmar B., Inthorn D., Schildberg F. W., Menger M. D. (2000) The thrombin antagonist hirudin fails to inhibit endotoxin-induced leukocyte/endothelial cell interaction and microvascular perfusion failure. Shock 14, 528–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kurose I., Miura S., Fukumura D., Suzuki M., Nagata H., Sekizuka E., Morishita T., Tsuchiya M. (1994) Attenuating effect of antithrombin III on the fibrinolytic activation and microvascular derangement in rat gastric mucosa. Thromb. Haemost. 71, 119–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roemisch J., Gray E., Hoffmann J. N., Wiedermann C. J. (2002) Antithrombin: a new look at the actions of a serine protease inhibitor. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 13, 657–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Opal S. M. (2003) Interactions between coagulation and inflammation. Scand. J. Infect Dis. 35, 545–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Souter P. J., Thomas S., Hubbard A. R., Poole S., Römisch J., Gray E. (2001) Antithrombin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced tissue factor and interleukin-6 production by mononuclear cells, human umbilical vein endothelial cells, and whole blood. Crit. Care Med. 29, 134–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dunzendorfer S., Kaneider N., Rabensteiner A., Meierhofer C., Reinisch C., Römisch J., Wiedermann C. J. (2001) Cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan-mediated regulation of human neutrophil migration by the serpin antithrombin III. Blood 97, 1079–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duensing T. D., Wing J. S., van Putten J. P. (1999) Sulfated polysaccharide-directed recruitment of mammalian host proteins: a novel strategy in microbial pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 67, 4463–4468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Minnema M. C., Chang A. C., Jansen P. M., Lubbers Y. T., Pratt B. M., Whittaker B. G., Taylor F. B., Hack C. E., Friedman B. (2000) Recombinant human antithrombin III improves survival and attenuates inflammatory responses in baboons lethally challenged with Escherichia coli. Blood 95, 1117–1123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fourrier F., Jourdain M., Tournois A., Caron C., Goudemand J., Chopin C. (1995) Coagulation inhibitor substitution during sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 21, S264–S268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baudo F., Caimi T. M., de Cataldo F., Ravizza A., Arlati S., Casella G., Carugo D., Palareti G., Legnani C., Ridolfi L., Rossi R., D'Angelo A., Crippa L., Giudici D., Gallioli G., Wolfler A., Calori G. (1998) Antithrombin III (ATIII) replacement therapy in patients with sepsis and/or postsurgical complications: a controlled double-blind, randomized, multicenter study. Intensive Care Med. 24, 336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inthorn D., Hoffmann J. N., Hartl W. H., Mühlbayer D., Jochum M. (1998) Effect of antithrombin III supplementation on inflammatory response in patients with severe sepsis. Shock 10, 90–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giudici D., Baudo F., Palareti G., Ravizza A., Ridolfi L., D' Angelo A. (1999) Antithrombin replacement in patients with sepsis and septic shock. Haematologica 84, 452–460 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Warren B. L., Eid A., Singer P., Pillay S. S., Carl P., Novak I., Chalupa P., Atherstone A., Pénzes I., Kübler A., Knaub S., Keinecke H. O., Heinrichs H., Schindel F., Juers M., Bone R. C., Opal S. M., and KyberSept Trial Study Group (2001) Caring for the critically ill patient. High-dose antithrombin III in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 286, 1869–1878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tanaka K. A., Levy J. H. (2007) Regulation of thrombin activity–pharmacologic and structural aspects. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 21, 33–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blajchman M. A. (1994) An overview of the mechanism of action of antithrombin and its inherited deficiency states. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 5, S5–S11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Muñoz E. M., Linhardt R. J. (2004) Heparin-binding domains in vascular biology. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 1549–1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kalle M., Papareddy P., Kasetty G., Tollefsen D. M., Malmsten M., Mörgelin M., Schmidtchen A. (2013) Proteolytic activation transforms heparin cofactor II into a host defense molecule. J. Immunol. 190, 6303–6310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rau J. C., Beaulieu L. M., Huntington J. A., Church F. C. (2007) Serpins in thrombosis, hemostasis and fibrinolysis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 5, 102–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Greenfield N., Fasman G. D. (1969) Computed circular dichroism spectra for the evaluation of protein conformation. Biochemistry 8, 4108–4116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sjögren H., Ulvenlund S. (2005) Comparison of the helix-coil transition of a titrating polypeptide in aqueous solutions and at the air-water interface. Biophys. Chem. 116, 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Picard V., Ersdal-Badju E., Bock S. C. (1995) Partial glycosylation of antithrombin III asparagine-135 is caused by the serine in the third position of its N-glycosylation consensus sequence and is responsible for production of the β-antithrombin III isoform with enhanced heparin affinity. Biochemistry 34, 8433–8440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lundqvist K., Herwald H., Sonesson A., Schmidtchen A. (2004) Heparin binding protein is increased in chronic leg ulcer fluid and released from granulocytes by secreted products of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Thromb. Haemost. 92, 281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Onoue S., Nemoto Y., Harada S., Yajima T., Kashimoto K. (2003) Human antithrombin III-derived heparin-binding peptide, a novel heparin antagonist. Life Sci. 73, 2793–2806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ganz T. (2001) Antimicrobial proteins and peptides in host defense. Semin Respir. Infect. 16, 4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang Y., Agerberth B., Löthgren A., Almstedt A., Johansson J. (1998) Apolipoprotein A-I binds and inhibits the human antibacterial/cytotoxic peptide LL-37. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33115–33118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oelschläger C., Römisch J., Staubitz A., Stauss H., Leithäuser B., Tillmanns H., Hölschermann H. (2002) Antithrombin III inhibits nuclear factor κB activation in human monocytes and vascular endothelial cells. Blood 99, 4015–4020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang L., Dinarvand P., Qureshi S. H., Rezaie A. R. (2014) Engineering D-helix of antithrombin in α-1-proteinase inhibitor confers antiinflammatory properties on the chimeric serpin. Thromb. Haemost. 112, 164–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nordahl E. A., Rydengård V., Nyberg P., Nitsche D. P., Mörgelin M., Malmsten M., Björck L., Schmidtchen A. (2004) Activation of the complement system generates antibacterial peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 16879–16884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nordahl E. A., Rydengård V., Mörgelin M., Schmidtchen A. (2005) Domain 5 of high molecular weight kininogen is antibacterial. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34832–34839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Malmsten M., Davoudi M., Schmidtchen A. (2006) Bacterial killing by heparin-binding peptides from PRELP and thrombospondin. Matrix Biol. 25, 294–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andersson E., Rydengård V., Sonesson A., Mörgelin M., Björck L., Schmidtchen A. (2004) Antimicrobial activities of heparin-binding peptides. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 1219–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Papareddy P., Kalle M., Kasetty G., Mörgelin M., Rydengård V., Albiger B., Lundqvist K., Malmsten M., Schmidtchen A. (2010) C-terminal peptides of tissue factor pathway inhibitor are novel host defense molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 28387–28398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Papareddy P., Rydengård V., Pasupuleti M., Walse B., Mörgelin M., Chalupka A., Malmsten M., Schmidtchen A. (2010) Proteolysis of human thrombin generates novel host defense peptides. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pasupuleti M., Roupe M., Rydengård V., Surewicz K., Surewicz W. K., Chalupka A., Malmsten M., Sörensen O. E., Schmidtchen A. (2009) Antimicrobial activity of human prion protein is mediated by its N-terminal region. PLoS One 4, e7358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rydengård V., Shannon O., Lundqvist K., Kacprzyk L., Chalupka A., Olsson A. K., Mörgelin M., Jahnen-Dechent W., Malmsten M., Schmidtchen A. (2008) Histidine-rich glycoprotein protects from systemic Candida infection. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hofstra J. J., Cornet A. D., de Rooy B. F., Vlaar A. P., van der Poll T., Levi M., Zaat S. A., Schultz M. J. (2009) Nebulized antithrombin limits bacterial outgrowth and lung injury in Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia in rats. Crit. Care 13, R145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schmidtchen A. (2000) Degradation of antiproteinases, complement and fibronectin in chronic leg ulcers. Acta Derm. Venereol. 80, 179–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mookherjee N., Brown K. L., Bowdish D. M., Doria S., Falsafi R., Hokamp K., Roche F. M., Mu R., Doho G. H., Pistolic J., Powers J. P., Bryan J., Brinkman F. S., Hancock R. E. (2006) Modulation of the TLR-mediated inflammatory response by the endogenous human host defense peptide LL-37. J. Immunol. 176, 2455–2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nijnik A., Madera L., Ma S., Waldbrook M., Elliott M. R., Easton D. M., Mayer M. L., Mullaly S. C., Kindrachuk J., Jenssen H., Hancock R. E. (2010) Synthetic cationic peptide IDR-1002 provides protection against bacterial infections through chemokine induction and enhanced leukocyte recruitment. J. Immunol. 184, 2539–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mookherjee N., Lippert D. N., Hamill P., Falsafi R., Nijnik A., Kindrachuk J., Pistolic J., Gardy J., Miri P., Naseer M., Foster L. J., Hancock R. E. (2009) Intracellular receptor for human host defense peptide LL-37 in monocytes. J. Immunol. 183, 2688–2696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Malmsten M., Kasetty G., Pasupuleti M., Alenfall J., Schmidtchen A. (2011) Highly selective end-tagged antimicrobial peptides derived from PRELP. PLoS One 6, e16400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jenssen H., Hancock R. E. (2010) Therapeutic potential of HDPs as immunomodulatory agents. Methods Mol. Biol. 618, 329–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Steinstraesser L., Kraneburg U., Jacobsen F., Al-Benna S. (2011) Host defense peptides and their antimicrobial-immunomodulatory duality. Immunobiology 216, 322–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. van der Does A. M., Beekhuizen H., Ravensbergen B., Vos T., Ottenhoff T. H., van Dissel J. T., Drijfhout J. W., Hiemstra P. S., Nibbering P. H. (2010) LL-37 directs macrophage differentiation toward macrophages with a proinflammatory signature. J. Immunol. 185, 1442–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rosenfeld Y., Papo N., Shai Y. (2006) Endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide) neutralization by innate immunity host-defense peptides. Peptide properties and plausible modes of action. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 1636–1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]