Background: Xenobiotics activate nuclear receptor PXR for detoxification and clearance. However, a role of PXR in regulating innate immunity remains unknown.

Results: PXR induced NLRP3 expression and triggered inflammasome activation in vascular ECs.

Conclusion: PXR plays an important role in the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in response to xenobiotics.

Significance: Our findings revealed a novel mechanism of innate immunity.

Keywords: Cellular Immune Response, Endothelial Cell, Innate Immunity, Nod-like Receptor (NLR), Pattern Recognition Receptor (PRR), Toll-like Receptor (TLR), Transcription Factor, Xenobiotic

Abstract

Pregnane X receptor (PXR) is a member of nuclear receptor superfamily and responsible for the detoxification of xenobiotics. Our previously study demonstrated that PXR is expressed in endothelial cells (ECs) and acts as a master regulator of detoxification genes to protect ECs against xenobiotics. Vascular endothelial cells are key sentinel cells to sense the pathogens and xenobiotics. In this study, we examined the potential function of PXR in the regulation of innate immunity in vasculatures. Treatments with PXR agonists or overexpression of a constitutively active PXR in cultured ECs increased gene expression of the key pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLR-2, -4, -9) and NOD-like receptors (NOD-1 and -2 and NLRP3). In particular, PXR agonism triggered the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and the ensuing cleavage and maturation of caspase-1 and interleukin-1β (IL-1β). Conversely, selective antagonism or gene silencing of PXR abrogated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. In addition, we identified NLRP3 as a transcriptional target of PXR by using the promoter-reporter and ChIP assays. In summary, our findings revealed a novel regulatory mechanism of innate immune by PXR, which may act as a master transcription factor controlling the convergence between the detoxification of xenobiotics and the innate immunity against them.

Introduction

The nuclear pregnane X receptor (PXR;2 NR1I2) is a key regulator of the body's defense against foreign substances, including pollutants, drugs, dietary compounds, and their metabolites (xenobiotics) (1–3). As a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily and ligand-activated transcription factor, PXR forms a heterodimer with retinoid X receptor-α and binds to the cognate DNA motifs (PXR-responsive element, PXRE) in the regulatory regions of the target genes. Upon the activation by a broad range of xenobiotics, PXR transcriptionally up-regulates the genes for detoxification, including the phase I cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and phase II-conjugating enzymes and transporters (4, 5). In addition to liver and intestines where PXR is highly expressed, we and others (6, 7) have recently found that PXR is also present in vascular cells such as endothelial cells (ECs) and smooth muscle cells. In ECs, PXR can be activated by hemodynamic shear stress and plays a central role in the maintenance of vascular homeostasis by detoxifying xenobiotics and protecting ECs from exogenous insults.

Endothelium, as the interface between the blood and vessel wall, is the first barrier coming into contact with xenobiotics or microbial entering circulation. Besides its essential functions in regulation of vascular tone, permeability, and coagulation, ECs also have important functions in both adaptive and innate immune responses. When perturbed by exogenous or endogenous insults, activated ECs recruit professional immunocytes, including monocytes and lymphocytes, by the induced expression of proinflammatory chemokines and adhesion molecules. Focal infiltration of macrophages and lymphocytes are important steps in adaptive immune response as well as in the pathogeneses of inflammatory diseases such as autoimmune disorders and atherosclerosis. Importantly, ECs are also considered as sentinels of innate immune system (8). ECs are known to possess major pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and RIG-I-like receptors (9–11). The inflammasome is a multiprotein complex consisting of NLRs, caspase-1, and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (PYCARD/ASC). Activation of inflammasome promotes the cleavage and maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 (12). NLRP3 inflammasome can be activated by a various bacterial, viral, and fungal pathogens and is required for host immune defense to these pathogenic infections (13–15). In light of the central role of PXR in regulating the detoxification of xenobiotics and the ability of xenobiotics to trigger innate immunity (16, 17), we sought to examine whether PXR plays a role in orchestrating these two closely related processes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Reagents

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were cultured in M199 supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 ng/ml recombinant human fibroblast growth factor, 90 μg/ml heparin, 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), and antibiotics. Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) and HepG2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Rifampicin was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). The antibodies against NLRP3, TLR4, TLR9, VP16, and IL-1β were from Abcam (Cambridge, UK), TLR2, TLR3, and caspase-1 p10 were from Bioss Inc. (Beijing, China), caspase-1 p20 was from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), and PXR and β-actin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise described.

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase PCR

Total RNA was isolated from HUVECs with the use of TRIzol reagent and reverse-transcribed (RT) with the Supercript reverse transcriptase and oligo(dT) primer. qRT-PCR were performed using iQTM SYBR Green PCR Supermix in the ABI 7500 real-time detection system. Primer sequences for human PXR, ABCB1, CYP3A4, NLRP1, NLRP3, ASC, CASP1, IL1B, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR9, NOD1, NOD2, and GADPH were shown in supplemental Table S1.

Western Blotting

Total proteins were extracted using the radioimmune precipitation assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology). The BCA reagents were used to measure the protein concentrations. Equal amounts of proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. The blots were immunoreacted with primary antibodies and appropriate secondary antibodies detected with use of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies and visualized by the ECL chemoluminescence system.

RNA Interference

The siRNA sequence targeting PXR was as follows: 5′-CAGGAGCAAUUCGCCAUUATT-3′ (sense) and 5′-UAAUGGCGAAUUGCUCCUGTT-3′ (antisense). The siRNA with scrambled sequence was used as negative control (NC siRNA). The double-stranded RNAs (100 nm) were transfected into HUVECs with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Promoter Constructs and Luciferase Reporter Assay

The 5′-flanking regions of the human NLRP3 genes were PCR-amplified by using a high fidelity DNA polymerase (TaqHifi, Invitrogen) from human genomic DNA, the primers were 5′-CGGGCTAGCGGTCATACGGTAGTTCTA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGGCTCGAGGCCAGAAGAAATTCCTAG-3′ (reverse). The fragment spanning from nucleotides −2977 to +151 (+1 as transcription start site 2 (18)) was subcloned into pGL3-basic plasmid containing the firefly luciferase reporter gene (Promega) with the use of NheI and XhoI restriction enzymes and verified with DNA sequencing. PXRE-luciferase (PXRE-Luc) promoter plasmid was described previously (7). BAECs were transfected with the promoter-reporter genes together with pRSV-β-gal using Lipofectamine 2000. Luciferase activities were measured 36 h later and normalized to β-galactosidase activity.

ChIP Assay

HUVECs were infected with Ad-VP-PXR (adenovirus expressing a constitutively active PXR) (7) for 36 h. Cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde and quenched before harvest and sonication. The sheared chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-PXR or control IgG and protein A/G Sepharose beads. After washing, the beads were eluted in 100 μl elution buffer (1% SDS, 100 mm NaHCO3). The eluted immunoprecipitates were digested with proteinase K, and DNA was extracted and underwent PCR with primers specific for the human NLRP3 promoter regions (supplemental Table S2). The DNA samples were analyzed by using quantitative PCR, and DNA binding was expressed as fold enrichment above control IgG.

Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± S.E. One-way analysis of variance or Student's t test was performed to determine statistical differences among or between groups using the SPSS (version 16.0, SPSS software, Chicago, IL). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

PXR Agonists Increased the Expression of Pattern Recognition Receptor Genes in ECs

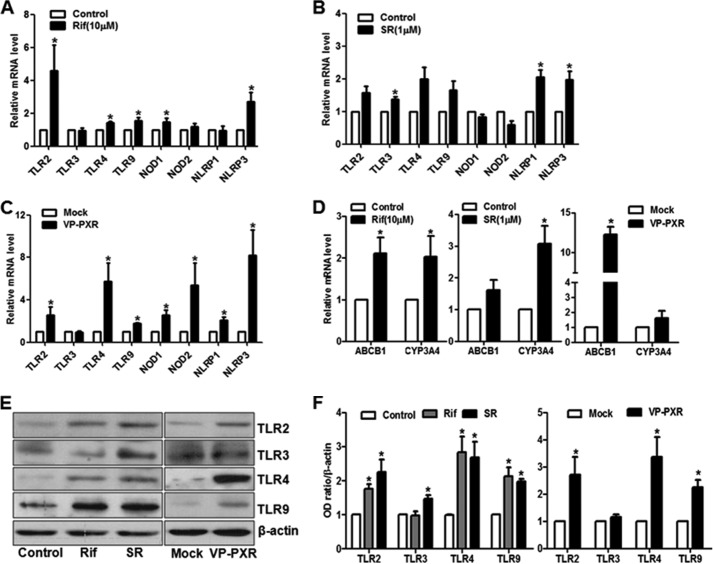

To examine the effect of PXR activation on the innate immunity-related receptors (pattern recognition receptors, PRRs), we treated HUVECs with the PXR agonists rifampicin (10 μm), SR12813 (1 μm), or vehicle control (dimethyl sulfoxide) for 24 h and assessed the mRNA levels of these PRR genes with qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 1A, the expression of TLR-2, TLR-4, TLR-9, NOD1, NLRP1, and NLRP3 were significantly increased by rifampicin. SR12813 also had a similar induction on TLR-2, TLR-4, NLRP1, and NLRP3 but not NOD1 (Fig. 1B). To rule out the potential off-target effect of individual agonists, we infected HUVECs with Ad-VP-PXR, a constitutively active PXR and confirmed the induction of TLR-2, TLR-4, TLR-9, NOD1, NOD2, NLRP1, and NLRP3 (Fig. 1C). As shown in Fig. 1D, expressions of CYP3A4 and ABCB1 (MDR1), the known PXR target genes, were increased by the both agonists and Ad-VP-PXR. Western blotting demonstrated that the protein levels of TLR-2, -4, and -9 were also increased by the PXR agonists and Ad-VP-PXR (Fig. 1, E and F). Thus, these results suggested that PXR activation led to the induction of the PRR genes in ECs, pointing to a potential role in innate immunity.

FIGURE 1.

PXR activation increased the expression of pattern recognition receptor genes in ECs. HUVECs were treated with rifampicin (Rif, 10 μm) (A) or SR12813 (SR, 1 μm) (B) for 24 h. C, HUVECs were infected with Ad-VP-PXR or mock infection for 36 h. The mRNA levels of TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR9, NOD1, NOD2, NLRP1, and NLRP3 were quantified by qRT-PCR. D, induction of CYP3A4 and ABCB1 (MDR1) by rifampicin, SR12813, and VP-PXR. E, protein levels of TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, and TLR9 were detected with Western blotting. F, the results were quantified and expressed in a bar graph. Data shown are as mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments expressed as fold change after normalization to GAPDH. *, p < 0.05 versus control.

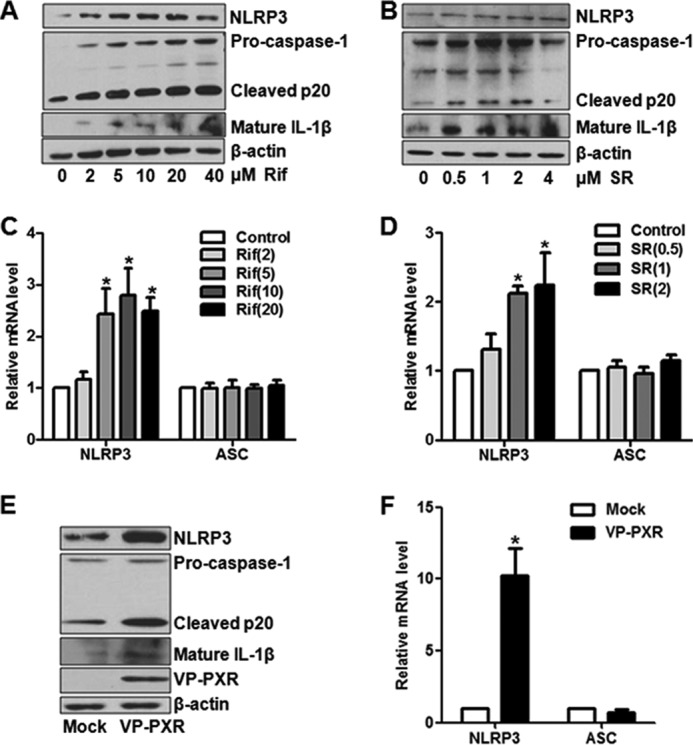

PXR Activated NLRP3 Inflammasome in ECs

To further investigate whether PXR activation also triggers the NLRP3 inflammasome activation, HUVECs were treated with rifampicin (0, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μm) or SR12813 (0, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μm) for 24 h. Western blotting demonstrated that either rifampicin or SR12813 dose-dependently increased the levels of NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1 p20, p10, and mature form IL-1β (Fig. 2, A and B, and supplemental Fig. 1). As measured by using qRT-PCR, mRNA levels of NLRP3 but not ASC was increased by the both PXR agonists (Fig. 2, C and D). Meanwhile, ABCB1 and CYP3A4 mRNA levels were also induced by rifampicin and SR in a dose-dependent manner (supplemental Fig. 2, A and B). In addition, overexpression of VP-PXR also increased the protein levels of NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1 and mature IL-1β (Fig. 2E), and mRNA level of NLRP3 (Fig. 2F). Taken together, these results indicated a role of PXR in the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in ECs.

FIGURE 2.

PXR triggered NLRP3 inflammasome activation in ECs. HUVECs were incubated with rifampicin (Rif; A) or SR12813 (SR; B) at various concentrations for 24 h. Protein levels of NLRP3 and other components in NLRP3 inflammasome were detected by using Western blotting. C and D, NLRP3 and ASC mRNA levels were assessed with the use of qRT-PCR and expressed as fold changes. E and F, HUVECs were infected with mock or Ad-VP-PXR for 36 h. Protein and mRNA levels of NLRP3 inflammasome were detected with Western blotting and qRT-PCR. The data shown are expressed as mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments.*, p < 0.05 versus control.

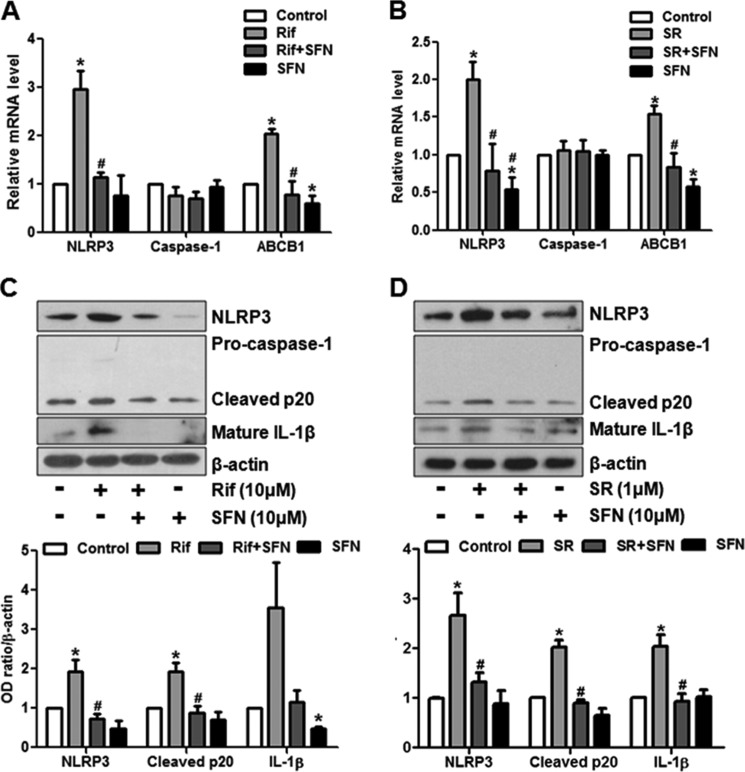

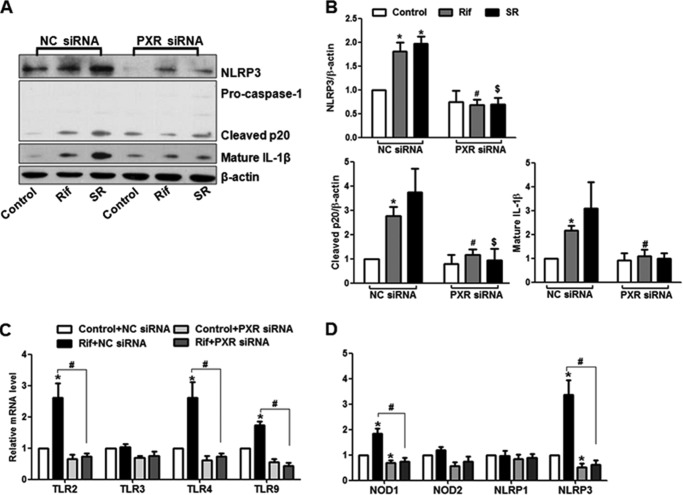

To ascertain the effects of rifampicin or SR12813 via PXR, we pretreated ECs with sulforaphane, an in vitro antagonist of human PXR for 4 h before the exposure to rifampicin or SR12813. As shown in Fig. 3, A and B, the rifampicin- or SR12813-induced NLRP3 were significantly diminished by sulforaphane. Similarly, sulforaphane also inhibited the NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Fig. 3, C and D). We also used the siRNA to silence the expression of endogenous PXR. As shown in supplemental Fig. 3, A and B, compared with scrambled siRNA, the transfection with PXR siRNA effectively diminished the expressions of PXR, and its target genes as well. In the PXR siRNA transfected ECs, activation of NLRP3 inflammasome by rifampicin or SR12813 was attenuated (Fig. 4, A and B). Notably, PXR knockdown also attenuated the rifampicin-induced mRNA levels of NLRP3 and other PRR genes (Fig. 4, C and D). Thus, these results demonstrated that rifampicin or SR12813 activated NLRP3 inflammasome via a PXR-dependent mechanism.

FIGURE 3.

PXR antagonist attenuated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. HUVECs were pretreated with sulforaphane (SFN, 10 μm) for 4 h before the exposure to rifampicin (Rif) or SR18123 (SR) for 24 h. A and B, the mRNA levels of NLRP3, CASP1, and ABCB1 were detected by using qRT-PCR. C and D, protein levels of NLRP3, caspase-1, and IL-1β and their matured forms were detected with Western blotting. The bar graphs represent the quantified results of Western blots. Data shown are as mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control; #, p < 0.05 versus rifampicin or SR18123.

FIGURE 4.

Knockdown of PXR abrogated the agonists-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. A, HUVECs were transfected with PXR siRNA or negative control (NC) siRNA for 48 h. After the treatments with PXR agonists (10 μm rifampicin (Rif) or 1 μm SR18123 (SR)) or vehicle control for 24 h, NLRP3 activation was detected with Western blotting. B, the bar graphs represent the quantified results of Western blots. The mRNA levels of NLRP3 and other PRR genes were measured with the use of qRT-PCR (C and D). Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control NC siRNA; #, p < 0.05 versus NC siRNA with rifampicin; $, p < 0.05 versus NC siRNA with SR18123.

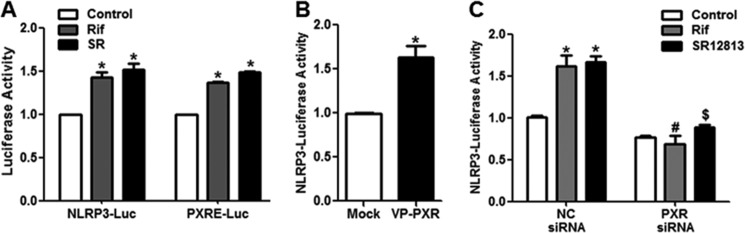

PXR Activation Induced the Activity of NLRP3 Promoters in ECs

To examine the effect of PXR on the transcriptional activation of the NLRP3 gene, we cloned a luciferase-reporter driven by the 3.1-kb PXR promoter fragment of the human NLRP3 gene. We performed the promoter reporter assay in BAECs. The luciferase assays showed that rifampicin or SR12813 activated the NLRP3 promoter as they did with the PXRE-luc reporter, which was used as a positive control (Fig. 5A). Consistently, adenoviral overexpression of the VP-PXR also increased the NLRP3 promoter activity (Fig. 5B). Importantly, PXR knockdown abolished the rifampicin- or SR12813-increased NLRP3-luciferase activity, indicating that the action of these xenobiotic ligands was PXR specific (Fig. 5C). These results suggested that PXR transactivated the NLRP3 promoter.

FIGURE 5.

PXR induced the NLRP3 promoter activity. A, BAECs were co-transfected with the NLRP3-luc (−2977/+151) or PXRE-luc plasmid and pCMX-PXR and then exposed to rifampicin (Rif) or SR18123 (SR) for 24 h. B, alternatively, BAECs were transfected with the NLRP3-luc and then infected with Ad-VP-PXR or mock virus for 36 h. C, BAECs were co-transfected with PXR siRNA or negative control (NC) siRNA and NLRP3-luc plasmid and then treated with rifampicin or SR12813 for 24 h. The luciferase activities were measured and normalized to β-gal activity. The data are expressed as fold change compared with control or mock infection. Data shown are as mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control or mock; #, p < 0.05 versus NC siRNA with rifampicin; $, p < 0.05 versus NC siRNA with SR18123.

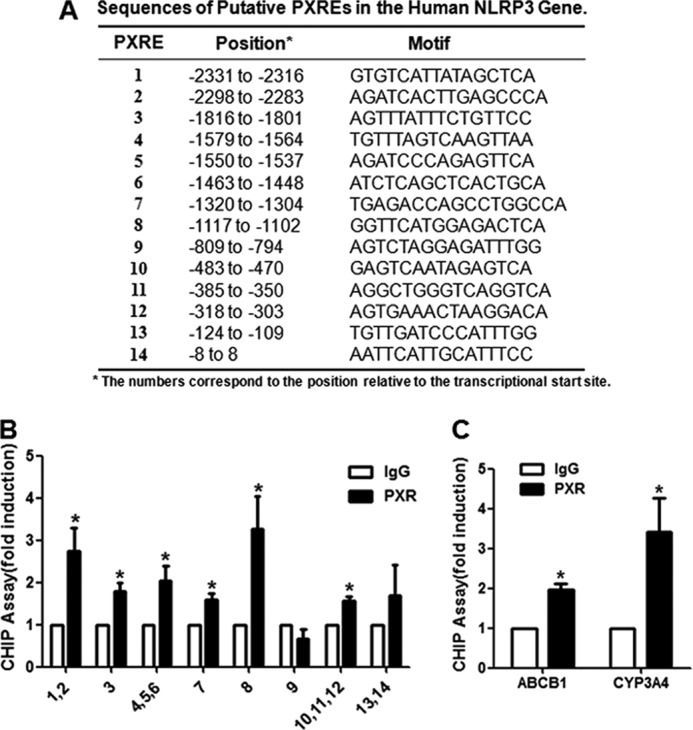

Identification of PXR-binding Sites in the NLRP3 Promoter

The core sequences of PXR-responsive elements are two hexamers (AGG/TTCA) half-sites in direct repeats spaced by three, four, or five bases (DR3, DR4, and DR5) or everted repeats spaced by six or eight bases (ER6 and ER8), depending on the gene-specific contexts (19). Examining the 5′-flanking region of the human NLRP3 gene revealed 14 putative PXR PXRE motifs (Fig. 6A). As shown in Fig. 6B, PXR was found to bind most of the fragments harboring the PXREs, as well as the fragments harboring the known PXRE motifs in the ABCB1 and CYP3A4 genes (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, the specificity of PXR binding to NLRP3 promoter was also verified by using ChIP assay in the PXR knockdown HepG2 cells (supplemental Fig. 4).

FIGURE 6.

Identification of the PXREs in the promoter region of the human NLRP3 gene. A, putative PXREs in the human NLRP3 gene promoter are listed with their positions (in relation to transcription start site) and core sequences. B, ChIP assays were performed in HUVECs overexpressing PXR with the use of anti-PXR antibody or IgG as control. The PXRE-bound sequences were quantified by using quantitative PCR with the primers flanking the putative PXREs in the NLRP3 gene promoter. C, the PXREs in the known PXR targets CYP3A4 and ABCB1 were used as positive controls. The PCR results were expressed as fold change compared with IgG control. Data shown are mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provided evidence that the PXR activation induced NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated innate immunity in cultured ECs. PXR activation-induced NLRP3 inflammasome is supported by several lines of evidence. These include the PXR agonists and VP-PXR increased the induction of the NLRP3, the cleavage of caspase-1 and the maturation of IL-1β. Furthermore, we identified NLRP3 as a direct target of PXR. This finding revealed that PXR is a master regulator at the convergence of two defensive mechanisms: the detoxification of and the innate immunity against the xenobiotics. This previously unrecognized mechanism may have important physiological relevance.

Vascular endothelium is among the first line of the body's defense system and senses xenobiotic substances as well as endogenous substances resulted from tissue damages. Such potentially dangerous milieu was recognized with a number of PRRs, including pathogen-associated molecular patterns and danger-associated molecular patterns. Induction and activation of the specific receptor elicit innate immune response to eliminate the insults and restore the tissue homeostasis. In this study, we found that the expression of NLRP3, NOD1, and TLR-2, TLR-4, and TLR-9 were increased in ECs exposed to xenobiotic ligands for PXR. Because the inductions of these PPRs are necessary to prime the inflammasome activation, simultaneous activation of PXR and innate immunity may represent a well organized protection against xenobiotics such as drugs and environmental pollutants. However, the activation of PXR initiates a detoxification machinery, which metabolizes and eliminates the xenobiotics from ECs by inducing a series of cytochrome P450 enzymes (for phase I detoxification), conjugating enzymes (for phase II detoxification) and transporters (for their efflux and uptake). Furthermore, activation of the inflammasome may facilitate the clearance and repair of the xenobiotics-resulted cellular damages.

NLRP3 is a key component of inflammasome and innate immunity system. In addition to sense pathogenic organisms, their pattern molecules, and environmental irritants, NLRP3 is also activated by a variety of intra- and extracellular danger signals such as ATP, glucose, cholesterol crystal, hyaluronan, and reactive oxygen species. Adequate expression and/or activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome are essential to the maintenance of immunological homeostasis, whereas the alterations in NLRP3 are associated with a number of immunological diseases such as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. Both protective and adverse effects of NLRP3 have been shown in age-related macular degeneration, an eye condition with choroidal neovascularization (20, 21). Excessive activation of NLRP3 in ECs by dyslipidemia, disturbed flow, and visfatin may contribute to the development of atherosclerosis and restenosis (22, 23). In addition to NLRP3, other PPRs, including TLR-2, TLR-3, TLR-4, TLR-9, NOD1, and NLRP1, are also induced by PXR. Their expressions in ECs were in consistent with a previous report (24). However, differential inductions of NOD1 and NLRP1 by rifampicin and SR12813 were observed (Fig. 1, A and B). This result may be due to the agonist-specific effect. Given that the constitutively active PXR caused a global induction of TLR-2, TLR-3, TLR-4, TLR-9, NOD1, NOD2, NLRP1, and NLRP3 (Fig. 1C) and that the attenuations by the antagonist or siRNA (Figs. 3 and 4), induced expressions of the PRRs are likely PXR-dependent.

Despite of the induction of the NLRP3 gene by various stimuli, the transcriptional mechanisms have been poorly understood. Several binding motifs were previously noticed for the proliferative and proinflammatory transcription factors, including SP1, c-MYB, AP-1, c-ETS (18), and recently, NF-κB (25). However, the induction of NLRP3 by PXR was unlikely via these motifs because the PXR activation were known to inhibit NF-κB and AP-1 both in the liver and ECs (7, 26) Instead, we found recurrent PXREs in the NLRP3 promoter and confirmed the PXR binding and activation, although the functionality of each individual motif was difficult to be dissected due to the multiplicity of the motifs. We analyzed the promoters of other PRR genes, including TLR-2, TLR-4, TLR-9, and also identified multiple PXREs in each of the TLR genes. Thus, it is plausible that these PRR genes are up-regulated by xenobiotics as the direct targets of PXR.

In conclusion, our results clearly demonstrated that PXR coordinated the activation of innate immunity and detoxification systems in vascular ECs. The convergence of the two distinct pathways may provide synergistic protection against the injuries caused by xenobiotic agents.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (81220108005 and 31430045) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (2010CB912502).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. 1–4.

- PXR

- pregnane X receptor

- EC

- endothelial cell(s)

- SR

- SR12813

- PRR

- pattern recognition receptor

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- PXRE

- PXR-responsive element

- CYP

- cytochrome P450

- BAEC

- bovine aortic endothelial cell

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- ASC

- apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain

- NC

- negative control.

REFERENCES

- 1. Willson T. M., Kliewer S. A. (2002) PXR, CAR and drug metabolism. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1, 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schuetz E. G., Brimer C., Schuetz J. D. (1998) Environmental xenobiotics and the antihormones cyproterone acetate and spironolactone use the nuclear hormone pregnenolone X receptor to activate the CYP3A23 hormone response element. Mol. Pharmacol. 54, 1113–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jacobs M. N., Nolan G. T., Hood S. R. (2005) Lignans, bacteriocides and organochlorine compounds activate the human pregnane X receptor (PXR). Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 209, 123–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gao J., Xie W. (2012) Targeting xenobiotic receptors PXR and CAR for metabolic diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 33, 552–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sonoda J., Rosenfeld J. M., Xu L., Evans R. M., Xie W. (2003) A nuclear receptor-mediated xenobiotic response and its implication in drug metabolism and host protection. Curr. Drug Metab. 4, 59–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Swales K. E., Moore R., Truss N. J., Tucker A., Warner T. D., Negishi M., Bishop-Bailey D. (2012) Pregnane X receptor regulates drug metabolism and transport in the vasculature and protects from oxidative stress. Cardiovasc. Res. 93, 674–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang X., Fang X., Zhou J., Chen Z., Zhao B., Xiao L., Liu A., Li Y. S., Shyy J. Y., Guan Y., Chien S., Wang N. (2013) Shear stress activation of nuclear receptor PXR in endothelial detoxification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 13174–13179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mai J., Virtue A., Shen J., Wang H., Yang X. F. (2013) An evolving new paradigm: endothelial cells–conditional innate immune cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 6, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mitchell J. A., Ryffel B., Quesniaux V. F., Cartwright N., Paul-Clark M. (2007) Role of pattern-recognition receptors in cardiovascular health and disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 1449–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Opitz B., Eitel J., Meixenberger K., Suttorp N. (2009) Role of Toll-like receptors, NOD-like receptors and RIG-I-like receptors in endothelial cells and systemic infections. Thromb. Haemost. 102, 1103–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xiao L., Liu Y., Wang N. (2014) New paradigms in inflammatory signaling in vascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 306, H317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schroder K., Tschopp J. (2010) The inflammasomes. Cell 140, 821–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ogura Y., Sutterwala F. S., Flavell R. A. (2006) The inflammasome: first line of the immune response to cell stress. Cell 126, 659–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Strowig T., Henao-Mejia J., Elinav E., Flavell R. (2012) Inflammasomes in health and disease. Nature 481, 278–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vladimer G. I., Marty-Roix R., Ghosh S., Weng D., Lien E. (2013) Inflammasomes and host defenses against bacterial infections. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16, 23–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cunha A. (2012) Innate immunity: pathogen and xenobiotic sensing - back to basics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Melo J. A., Ruvkun G. (2012) Inactivation of conserved C. elegans genes engages pathogen- and xenobiotic-associated defenses. Cell 149, 452–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anderson J. P., Mueller J. L., Misaghi A., Anderson S., Sivagnanam M., Kolodner R. D., Hoffman H. M. (2008) Initial description of the human NLRP3 promoter. Genes Immun. 9, 721–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hariparsad N., Chu X., Yabut J., Labhart P., Hartley D. P., Dai X., Evers R. (2009) Identification of pregnane-X receptor target genes and coactivator and corepressor binding to promoter elements in human hepatocytes. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1160–1173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Doyle S. L., Campbell M., Ozaki E., Salomon R. G., Mori A., Kenna P. F., Farrar G. J., Kiang A. S., Humphries M. M., Lavelle E. C., O'Neill L. A., Hollyfield J. G., Humphries P. (2012) NLRP3 has a protective role in age-related macular degeneration through the induction of IL-18 by drusen components. Nat. Med. 18, 791–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marneros A. G. (2013) NLRP3 inflammasome blockade inhibits VEGF-A-induced age-related macular degeneration. Cell Rep. 4, 945–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xiao H., Lu M., Lin T. Y., Chen Z., Chen G., Wang W. C., Marin T., Shentu T. P., Wen L., Gongol B., Sun W., Liang X., Chen J., Huang H. D., Pedra J. H., Johnson D. A., Shyy J. Y. (2013) Sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in endothelium mediates hemodynamic-induced atherosclerosis susceptibility. Circulation 128, 632–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xia M., Boini K. M., Abais J. M., Xu M., Zhang Y., Li P. L. (2014) Endothelial NLRP3 inflammasome activation and enhanced neointima formation in mice by adipokine visfatin. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 1617–1628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yin Y., Yan Y., Jiang X., Mai J., Chen N. C., Wang H., Yang X. F. (2009) Inflammasomes are differentially expressed in cardiovascular and other tissues. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 22, 311–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Qiao Y., Wang P., Qi J., Zhang L., Gao C. (2012) TLR-induced NF-κB activation regulates NLRP3 expression in murine macrophages. FEBS Lett. 586, 1022–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou C., Tabb M. M., Nelson E. L., Grün F., Verma S., Sadatrafiei A., Lin M., Mallick S., Forman B. M., Thummel K. E., Blumberg B. (2006) Mutual repression between steroid and xenobiotic receptor and NF-κB signaling pathways links xenobiotic metabolism and inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2280–2289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.