Abstract

A study on binding of antitumor chelerythrine to human telomeric DNA/RNA G-quadruplexes was performed by using DNA polymerase stop assay, UV-melting, ESI-TOF-MS, UV-Vis absorption spectrophotometry and fluorescent triazole orange displacement assay. Chelerythrine selectively binds to and stabilizes the K+-form hybrid-type human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex of biological significance, compared with the Na+-form antiparallel-type DNA G-quadruplex. ESI-TOF-MS study showed that chelerythrine possesses a binding strength for DNA G-quadruplex comparable to that of TMPyP4 tetrachloride. Both 1:1 and 2:1 stoichiometries were observed for chelerythrine's binding with DNA and RNA G-quadruplexes. The binding strength of chelerythrine with RNA G-quadruplex is stronger than that with DNA G-quadruplex. Fluorescent triazole orange displacement assay revealed that chelerythrine interacts with human telomeric RNA/DNA G-quadruplexes by the mode of end- stacking. The relative binding strength of chelerythrine for human telomeric RNA and DNA G-quadruplexes obtained from ESI-TOF-MS experiments are respectively 6.0- and 2.5-fold tighter than that with human telomeric double-stranded hairpin DNA. The binding selectivity of chelerythrine for the biologically significant K+-form human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex over the Na+-form analogue, and binding specificity for human telomeric RNA G-quadruplex established it as a promising candidate in the structure-based design and development of G-quadruplex specific ligands.

Telomeres are the specialized and functional DNA-protein complexes at the end of all eukaryotic linear chromosomes which provide protection against gene erosion at cell divisions, chromosomal non-homologous end-joinings and nuclease attacks1. DNA of telomere in vertebrates consists of tandem repeats of the sequence dTTAGGG. Human telomeric DNA is typically 5–8 kb long with a 3′ protruding single-stranded overhang of 100–200 nt. Each cell division leads to a 50–200 base loss of the telomere due to the end-replication problem of telomere, which eventually results in critically short telomeres and ultimately triggers programmed cell death2. The intervention of telomere maintenance processes provides an attractive and potentially broad-spectrum anticancer strategy in the design of anticancer therapeutics because one of the key features of cancer cells is to circumvent telomere shortening processes3,4. More than 85% of cancer cells overexpress telomerase, a reverse transcriptase that elongates the telomeres by appending additional telomeric repeats. This process makes cancer cells immortal and allows continual cell division without telomere shortening and subsequent senescence5,6. It has been found that human telomere forms G-quadruplex structures in vivo7,8 and in cell extracts9. In addition to maintaining chromosome stability10, telomeric G-quadruplexes present obstacles for recruitment of telomerase11 and translocation of the DNA replication machinery12. Currently, telomeric G-quadruplex targeting with the aid of small organic molecules is emerging as a novel approach to discover cancer therapeutics13.

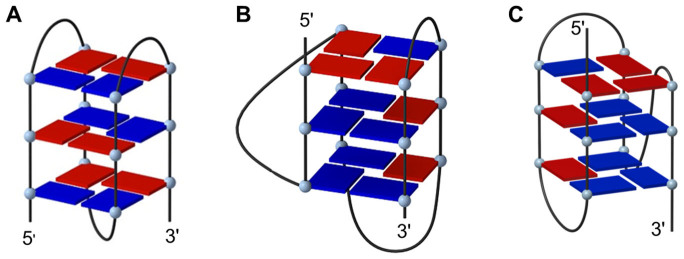

The single-stranded G-rich telomeric DNA sequence can fold into an intramolecular G-quadruplex in the presence of monovalent cations, such as K+ or Na+. In the presence of Na+ ion, the human telomeric sequence folds into an intramolecular basket-type G-quadruplex structure (Figure 1A), which has one diagonal and two lateral loops, with the guanine columns in an antiparallel arrangement14. However, the folding structure of human telomeric sequence in K+ solution has been characterized by NMR to be in equilibrium between two hybrid-type mixed parallel/antiparallel strands of G-quadruplex conformations, i.e. Hybrid-1 (Figure 1B) and Hybrid-2 (major conformation, Figure 1C)15,16,17. The Hybrid-1 structure has sequential side-lateral-lateral loops with the first TTA loop adopting the double-chain-reversal conformation, whereas the Hybrid-2 structure has lateral-lateral-side loops with the last TTA loop adopting the double-chain-reversal conformation15,16,17. Furthermore, the K+ readily converts the Na+-form conformation to the K+-form hybrid-type G-quadruplex15. As the intracellular K+ concentration is much greater than that of Na+, the K+-form hybrid-type of human telomeric G-quadruplex structures are considered to be of biological significance.

Figure 1. The folding topologies of three types of intramolecular G-quadruplex structures for human telomeric DNA sequence.

(A) Na+-form antiparallel G-quadruplex structure stabilized by Na+ ion. (B) Hybrid-1 type and (C) Hybrid-2 type (major conformation) of K+-form mixed parallel/antiparallel G-quadruplex structure stabilized by K+ ion. Blue and red boxes represent guanine bases in the anti and syn conformations, respectively.

Telomere is transcribed into telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA)18,19. These non-coding RNA molecules contain subtelomeric-derived sequences with an average of 34 rGGGUUA repeats at their 3′ end20. Various regulatory functions have been assigned to TERRA, such as heterochromatin regulation, telomerase inhibition, telomere length regulation and telomere protection21,22,23,24. Importantly, TERRA RNA G-quadruplexes were found in living cells25. TERRA is also regarded as a promising cancer therapeutic target although the functional significance of TERRA G-quadruplex is still in need of robust experimental support20. It has been shown by NMR spectroscopy26,27 and by X-ray crystallography28 that human telomeric repeat-containing RNA sequence r(UUAGGG)4 folds into a parallel G-quadruplex in monovalent cation solution that is more stable than its DNA counterparts.

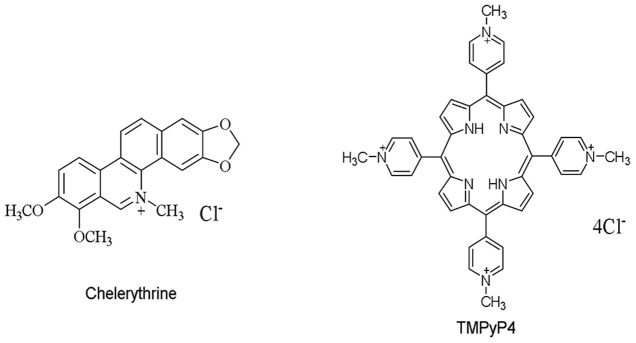

Chelerythrine (Figure 2), a natural benzophenanthridine alkaloid, possesses diverse pharmacological activities, including potent anti-cancer and cytotoxic activities29,30,31. Recently, it was found that chelerythrine recognizes G-quadruplex in c-kit promoter with a high affinity via end-stacking mode32. G-quadruplex induction ability of chelerythrine has been studied by means of CD spectroscopy, CD-melting experiments and ESI-MS techniques. This alkaloid can transform random coil of human telomeric DNA to antiparallel G-quadruplex structure33. To the best of our knowledge, it has never been reported in the aspect of its binding with any preformed human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex, neither the K+-form nor the Na+-form of DNA G-quadruplex structures, which is still in need of a comprehensive and comparative investigation. In addition, it still remains unexplored in the interaction of chelerythrine with human telomeric RNA G-quadruplex. In this study, we employed DNA polymerase stop assay, UV-melting study, UV-Vis absorption spectrophotometry, fluorescent triazole orange (TO) displacement assay and electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF-MS) to investigate the binding of chelerythrine to both K+-form and Na+-form human telomeric DNA G-quadruplexes. The conformation selectivity of chelerythrine to human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex was consequently examined by comparing its binding with two types of DNA G-quadruplexes. Moreover, the interaction of chelerythrine with human telomeric RNA G-quadruplex was also explored and its binding capacity with RNA G-quadruplex was compared to that with DNA counterpart. Finally, the mode of chelerythrine binding with human telomeric both DNA and RNA G-quadruplexes was studied.

Figure 2. Chemical structures of chelerythrine and TMPyP4.

Results

Binding of chelerythrine to the K+-form hybrid-type human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex

As a sensitive and effective method for screening G-quadruplex-interactive agents with potential clinical utility, DNA polymerase stop assay makes use of the fact that G-rich DNA templates present obstacles by formation of intramolecular G-quadruplex structures in the presence of potassium or sodium cation to DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase. The ligands which can stabilize an intramolecular G-quadruplex structure lead to enhanced arrest of DNA synthesis in the presence of monovalent cation of K+ or Na+ 34,35.

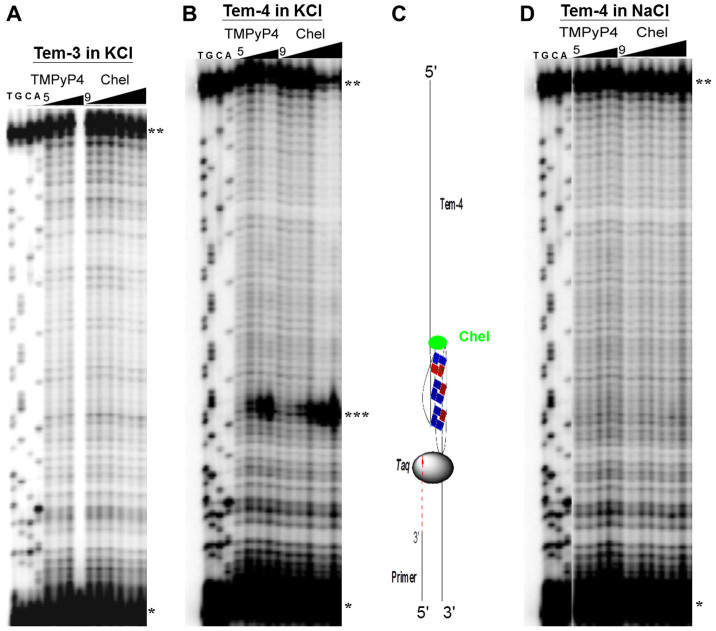

The stabilizing effect of chelerythrine on the K+-form DNA G-quadruplex was firstly investigated by DNA polymerase stop assay34 in the presence of K+ cation. The experiment was carried out in 50 mM K+ containing buffer of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.50) by using DNA template tem-3 and tem-4 (Table S1) which contained 3 and 4 human telomeric repeats TTAGGG, respectively. TMPyP4, a well-studied G-quadruplex DNA binder (Figure 2), was used as a positive control. As a result (Figures 3A and 3B), neither TMPyP4 nor chelerythrine arrested DNA synthesis for template-3, because it couldn't produce a G-quadruplex structure with only three human telomeric G-rich repeats. However, chelerythrine showed the same Taq polymerase inhibition activity as that of TMPyP4 by stabilizing the G-quadruplex structure present in tem-4 containing four telomeric repeats in the presence of K+ (Figure 3B). For chelerythrine, a series of concentration-dependent paused bands appeared at the very beginning of the G-quadruplex forming site, i.e., the first guanine site of G-rich repeats in tem-4 (from 3′ to 5′). This gel result showed that chelerythrine binds to and stabilizes the K+-form DNA G-quadruplex in a concentration-dependent manner.

Figure 3. Concentration-dependent inhibition of Taq polymerase DNA synthesis by G-quadruplex binding ligands.

(A) on the DNA templates Tem-3 and (B, D) Tem-4 at 42°C in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.50) containing (A, B) 50 mM KCl or (D) 50 mM NaCl. The lane markers T, G, C, and A indicate the bases on the template strand. (A) Lanes 5–8: TMPyP4 (0, 0.3, 1 and 3 μM) and lanes 9–14: chelerythrine (0, 0.3,1, 3, 10 and 30 μM) for Tem-3; (B) Lanes 5–8: TMPyP4 (0, 0.1, 0.3 and 1 μM) and lanes 9–14: chelerythrine (0, 0.1, 0.3,1, 3 and 10 μM) for Tem-4; (D) Lanes 5–8: TMPyP4 (0, 0.1, 0.3 and 1 μM) and lanes 9–15: chelerythrine (0, 0.1, 0.3,1, 3, 10 and 30 μM) for Tem-4. * primers, ** full-length products, *** paused bands. (C) A schematic illustration for DNA polymerase stop assay with 4 telomeric repeats.

DNA melting temperature (Tm) measurement was utilized to further study the binding behavior of chelerythrine with the preformed K+-form hybrid type DNA G-quadruplex formed by d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] in 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH7.43) containing 100 mM KCl (Figure S1A–B). The melting curve of d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] showed a reverse “S” shape at 295 nm with a Tm value of 67.1°C, indicating the formation of K+-form hybrid type G-quadruplex structure. The Tm value of the K+-form DNA G-quadruplex was increased 6.2°C by chelerythrine (Figure S1A) in a 2:1 molar ratio of ligand-to-DNA, implying that chelerythrine provided thermal stability to the K+-form DNA G-quadruplex.

Binding of chelerythrine to the Na+-form antiparallel-type human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex

The Na+-form human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex is another principal secondary intramolecular four-stranded DNA structure. The stabilizing effect of chelerythrine on the Na+-form DNA G-quadruplex structure was also investigated by DNA polymerase stop assay in the presence of Na+ cation. As shown in Figure 3D, the gel result in the presence of Na+ ion is completely different from that conducted in K+ condition (Figure 3B). Neither TMPyP4 nor chelerythrine exhibited any significant paused band on Tem-4 at the tested concentrations (from 0 to 30 μM for chelerythrine) in the presence of 50 mM NaCl. This suggested that chelerythrine can not sufficiently stabilize the Na+-form DNA G-quadruplex to cease the polymerase reaction even at a high concentration of 30 μM, which is completely different from that of the K+-form DNA G-quadruplex (Lanes 12–14 in Figure 3B). The obvious difference of gel results manifested that chelerythrine selectively stabilizes the K+-form hybrid type human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex.

To further examine the effect of chelerythrine on the Na+-form DNA G-quadruplex structure, thermal denaturation profiles of d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] in 100 mM NaCl solution were monitored at 295 nm in the absence and presence of chelerythrine (Figure S1C–D). Apparently, there was no significant increase of Tm value of d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] by chelerythrine even in a 6:1 alkaloid-to-DNA molar ratio. This UV-melting result together with the data of polymerase stop assay conducted in 50 mM NaCl solution indicated that chelerythrine does not interact with the Na+-form human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex or weakly binds to the Na+-form G-quadruplex which cann't be detected under the tested condition. The completely different binding behaviour of chelerythrine to the Na+-form and K+-form DNA G-quadruplexes revealed that this alkaloid showed binding specificity for the intramolecular human telomeric K+-form DNA G-quadruplex.

Binding of chelerythrine to human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex by ESI-TOF-MS

The high resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry (TOF-MS), connected with a soft electrospray ionization (ESI) source, has been playing a powerful and active role in the investigation of noncovalent interaction of small organic molecules with nucleic acids. It is a highly sensitive and reliable method to determine stoichiometries, relative binding affinities and equilibrium association constants of drug-DNA complexes36,37,38. Quantitative determination of binding constants for minor groove binders with different DNA duplexes has been demonstrated39, and the interaction of ligands with G-quadruplex structures has also been successfully investigated32,40,41,42,43.

A remarkable difference should be taken into consideration between the gas-phase method of ESI-TOF-MS and the solution-phase methods in the preparation of complexes of the alkaloid with DNA G-quadruplex. The G-quadruplex stabilizing metal ion K+ cation should be replaced by NH4+ ion in ESI-TOF-MS study, because NH4+ ion is the best choice for ESI-MS experiment and it can also stabilize intramolecular G-quadruplex structures. CD spectroscopy was thus used to compare the conformational characteristics of chelerythrine-G-quadruplex complex between in K+ and NH4+ cation solutions. As a result, the CD spectrum of d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] with chelerythrine in 100 mM NH4OAc solution exhibited similar pattern to that in 100 mM KCl solution (Figure S2). Consequently, the complex of preformed human telomeric DNA G-quadurplex with chelerythrine in ammonium acetate solution for ESI-TOF-MS experiments is regarded as a homogeneous one with that folded in KCl solution.

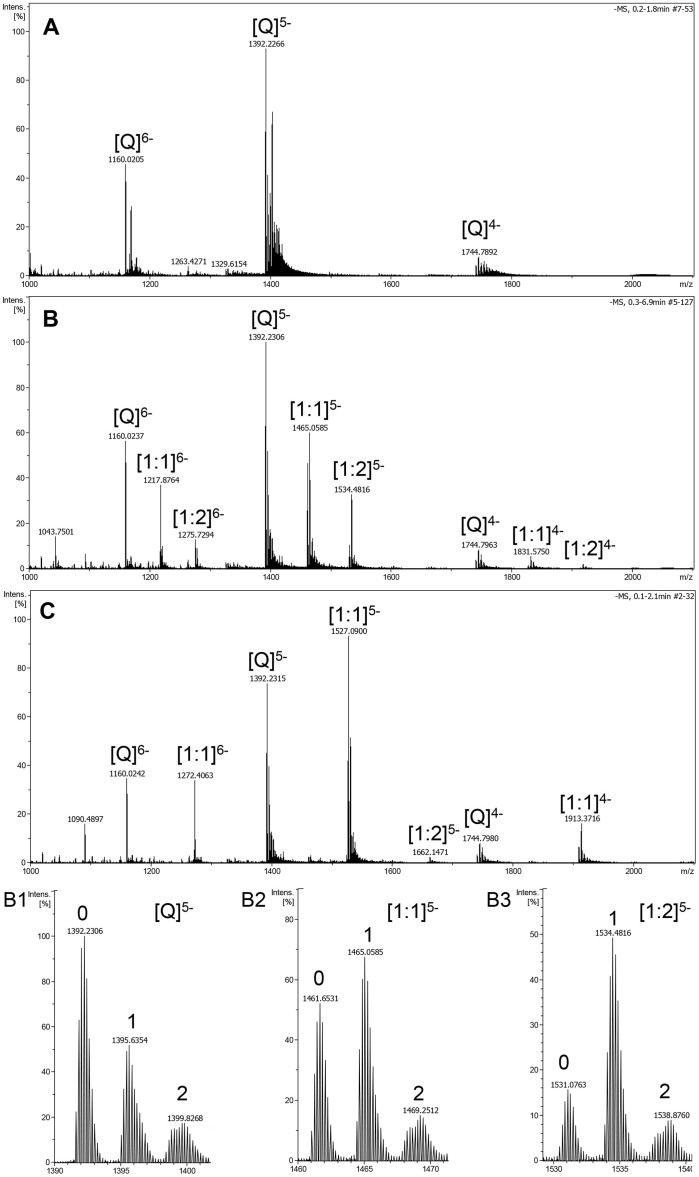

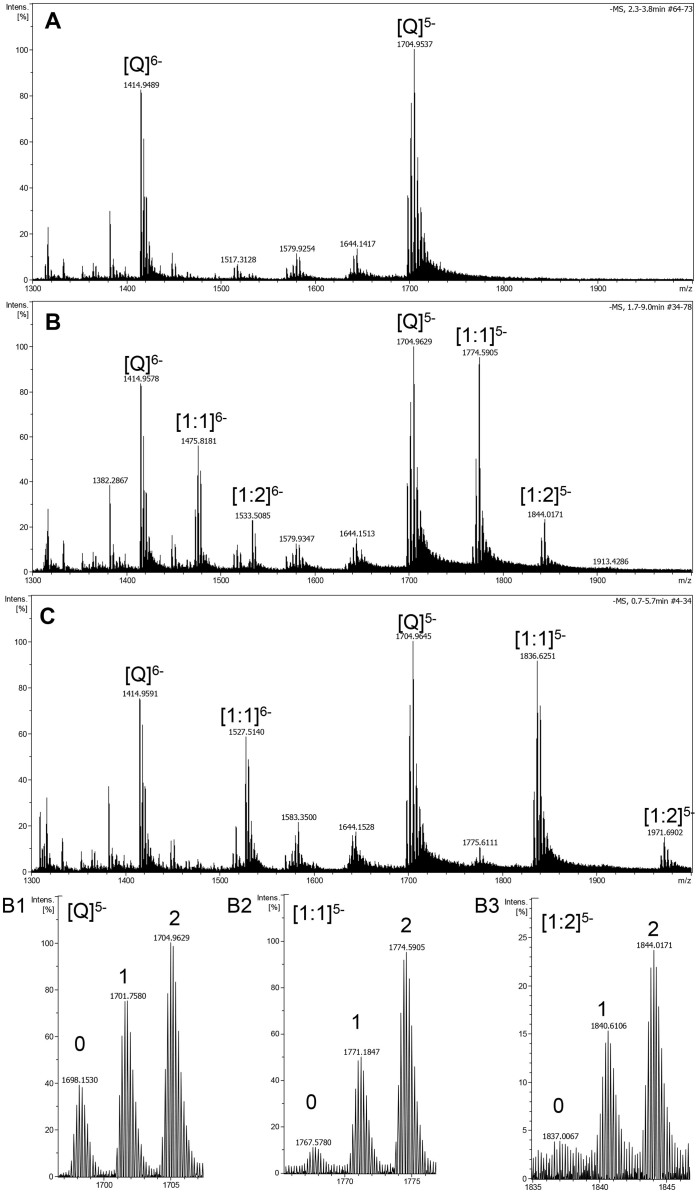

ESI-TOF-MS was therefore utilized to directly observe the noncovalent complexes of chelerythrine with human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex formed by the sequences of both 22 nt d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] (Figure 4) and 27 nt d[(TTAGGG)4TTA] (Figure 5). The free G-quadruplex (Q) exhibited ions mainly in the charge states of −5 and −6 in both Figure 4A and 5A. In each charge state, there were three ions corresponding to [M − x H]x− (the lone oligodeoxynucleotide), [M + NH4+ − (x + 1) H]x− (one NH4+ ion adduct), and [M + 2 NH4+ − (x + 2) H]x− (two NH4+ ions adduct), respectively. It was found that the ammonium ions were much more stably conserved between G-tetrads of 27 nt G-quadruplex (Figure 5B1) than those of 22 nt G-quadruplex (Figure 4B1) under the same mass spectrometric conditions. Both 1:1 and 2:1 complexes of chelerythrine and DNA G-quadruplex were observed at m/z corresponding to [M + Che − 6H]5−, [M + NH4+ + Che − 7H]5−, [M + 2NH4+ + Che − 8H]5− (Figure 4B2 and 5B2) and [M + 2Che − 7H]5−, [M + NH4+ + 2Che − 8H]5−, [M + 2NH4+ + 2Che − 9H]5− (Figure 4B3 and 5B3) when an equal mole of chelerythrine was added to DNA. The complex peaks with two NH4+ ion adducts became more predominant than those with one NH4+ ion adduct or none (Figure 5B2–5B3 and Figure S3B). This indicated that the G-quadruplex structure stabilized by chelerythrine holds NH4+ ions inserted between G-tetrads more tightly than free G-quadruplex in the course of being introduced into the gas phase. In other words, chelerythrine-bound G-quadruplex is more stable than when it is unbound due to the great stability provided by chelerythrine42.

Figure 4. Negative ESI-TOF-MS spectra of human telomeric sequence d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] (Q).

(A) without drug, (B) with equimolar of chelerythrine, and (C) with equimolar of TMPyP4 tetrachloride. B1–B3 are the enlargements of the distribution of ammonium adducts for the five charge state of the free G-quadruplex, [1:1] and [1:2] complexes of DNA with chelerythrine. The numbers represent the number of ammonium adducts.

Figure 5. Negative ESI-TOF-MS spectra of human telomeric sequence d[(TTAGGG)4TTA] (Q).

(A) without drug, (B) with equimolar of chelerythrine, and (C) with equimolar of TMPyP4 tetrachloride. B1–B3 are the enlargements of the distribution of ammonium adducts for the five charge state of the free G-quadruplex, [1:1] and [1:2] complexes of DNA with chelerythrine. The numbers represent the number of ammonium adducts.

The relative binding affinity (RBA) of chelerythrine was calculated to evaluate the binding capacity of chelerythrine to human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex by the equation: RBA = Σcomplex peaks areas/Σfree G-quadruplex peaks areas42, and subsequently compared to that of the reference G-quadruplex binder of TMPyP4 tetrachloride43 (Figure 4C and 5C). The average of RBA value was determined from three independent measurements. An equal RBA value was obtained for chelerythrine binding with both 22 nt (1.05 ± 0.04) and 27 nt (1.08 ± 0.08) human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex (Table 1). In addition, chelerythrine showed an almost equivalent RBA value to that of TMPyP4 tetrachloride [(1.15 ± 0.10) for 22 nt G-quadruplex, (1.10 ± 0.12) for 27 nt G-quadruplex] in a 1:1 molar ratio of ligand-to-DNA, suggesting that the binding strength of chelerythrine with human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex is comparable to that of TMPyP4 tetrachloride.

Table 1. Relative binding affinities of chelerythrine with the intramolecular human telomeric G-quadruplex, double-stranded and single-stranded nucleic acids obtained by ESI-TOF-MS method.

| Nucleic acids | RBA |

|---|---|

| r[(UUAGGG)4UUA] (RNA G-quadruplex) | 2.51 ± 0.13 |

| d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] (22 nt DNA G-quadruplex) | 1.05 ± 0.04 |

| d[(TTAGGG)4TTA] (27 nt DNA G-quadruplex) | 1.08 ± 0.08 |

| d[(TTAGGG)2TTA(CCCTAA)2] (ds-DNA) | 0.42 ± 0.03 |

| d[(TTAGGG)2TTAAAATTAGGGTTA] (ss-DNA) | 0.21 ± 0.02 |

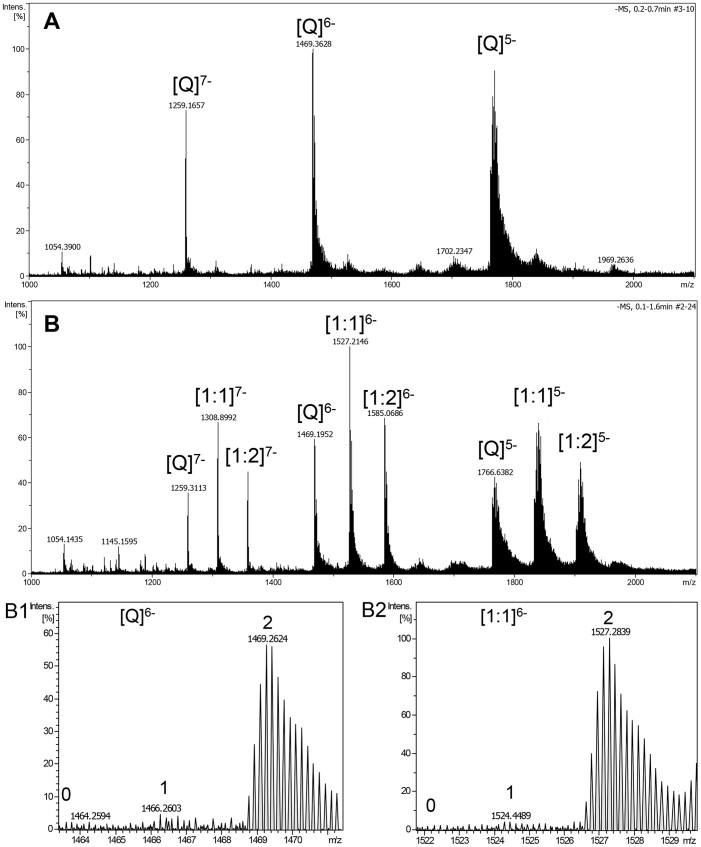

Binding of chelerythrine to human telomeric RNA G-quadruplex by ESI-TOF-MS

The binding of chelerythrine with human telomeric RNA G-quadruplex r[(UUAGGG)4UUA] was also studied under the same ESI-TOF-MS condition as that of DNA counterpart (Figure 6). As shown in the ESI-TOF-MS spectra of r[(UUAGGG)4UUA] (Figure 6A), the three predominant ions with m/z value of 1259.1657 ([M + 2NH4+ − 9H]7−), 1469.3628 ([M + 2NH4+ − 8H]6−) and 1763.4552 ([M + 2NH4+ − 7H]5−) correspond to two NH4+ ion adducts of r[(UUAGGG)4UUA], indicating the high stability of RNA G-quadruplex in the gas phase. Similar to that of DNA G-quadruplex, chelerythrine binds to human telomeric RNA G-quadruplex with 1:1 and 2:1 stoichiometry complexes when 1:1 molar ratio of alkaloid-to-RNA was used. Moreover, it was observed that all peaks of complexes contained two NH4+ ions which resided between three G-tetrads of RNA G-quadruplex. The RBA value of chelerythrine was 2.51 with human telomeric RNA G-quadruplex (Table 1).

Figure 6. Negative ESI-TOF-MS spectra of human telomeric sequence r[(UUAGGG)4UUA] (Q).

(A) without drug, and (B) with equimolar of chelerythrine. B1–B2 are the enlargements of the distribution of ammonium adducts for the six charge state of the free G-quadruplex and [1:1] complex of RNA with chelerythrine. The numbers represent the number of ammonium adducts.

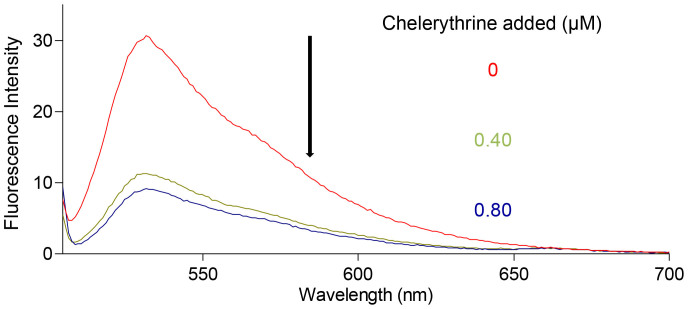

Mode of chelerythrine's binding to human telomeric DNA/RNA G-quadruplexes by fluorescent triazole orange displacement assay and UV-Vis spectrophotometry

Triazole orange (TO) is a dye which end-stacks on the two external quartets of a G-quadruplex with high affinity (Ka = 3 × 106 M−1)56. TO is highly fluorescent upon interaction with G-quadruplex DNA (~500- to 3000-fold exaltation) whereas is completely quenched when free in solution, which ensures that the displacement of a given ligand can be easily monitored by the decrease of TO fluorescence (λmax = 530 nm) with an excitation wavelength at 501 nm44,45. Therefore, fluorescent TO displacement assay was utilized to investigate the binding mode of chelerythrine with human telomeric DNA (Figure 7, Figure S4A–C) and RNA G-quadruplexes (Figure S4D). As illustrated in Figure 7, the percent fluorescence decrease of TO was 63.1% when 0.8 equivalent of chelerythrine was added to the solution of TO-bound G-quadruplex (Table S2), indicating that most of the G-quadruplex-bound TO has been driven out by chelerythrine. This provided solide evidence that chelerythrine binds to human telomeric DNA/RNA G-quadruplex in a mode of end-stacking.

Figure 7. Fluorescence spectra of triazole orange (0.5 μM) with d[AGGG(TTAGCG)3] (0.25 μM).

The spectra with the excitation at 501 nm were recorded in the presence of 0, 0.40 and 0.80 μM of chelerythrine, respectively, in 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.43) containing 100 mM KCl.

The mode of chelerythrine binding to human telomeric both RNA and DNA G-quadruplexes was subsequently investigated by means of ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry (Figure S5). The UV-Vis absorption spectra of chelerythrine with RNA and DNA G-quadruplex in a 2:1 molar ratio displayed red shifts of 10 nm (from 268 nm to 278 nm) and 2 nm (from 268 nm to 270 nm) associated with 73.4% and 39.4% hypochromism, respectively (Figure S5). These striking spectral changes exhibited π-π stacking interactions between the chromophore of chelerythrine and the G-tetrad. Taken the results from TO displacement assay and UV-Vis spectrophotometry together, it was implied that chelerythrine binds to G-quadruplex via the mode of end-stacking. Moreover, mass spectrometry also provided supporting information on the binding mode of chelerythrine to the human telomeric DNA/RNA G-quadruplex. The complex peaks with two ammonium cations, i.e., [Q + 2NH4+ + Alkaloid − 8H]5− and [Q + 2NH4+ + 2Alkaloid − 9H]5− in Figure 5B and 6B, indicated that two molecules of chelerythrine bind to the DNA/RNA G-quadruplex by end stacking mode, as two ammonium ions were conserved between three G-tetrads42,46,47. This G-quadruplex interacting mode of chelerythrine was also consistent with that of berberine, an isoquinoline alkaloid which was found to be stacked onto the two external G-tetrads determined by both X-ray diffraction48 and molecular modeling methods49. In addition, the UV-Vis absorption spectra of chelerythrine complexed with RNA G-quadruplex showed a more remarkable change of 8 nm bathochromic shift and 34% hypochromicity than those with DNA counterpart. This significant spectral change of chelerythrine with RNA G-quadruplex over DNA analogue provided supporting evidence that chelerythrine shows a preference for human telomeric RNA G-quadruplex over DNA counterpart.

Selectivity of chelerythrine to human telomeric G-quadruplex over double-stranded and single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides

In order to get an insight into G-quadruplex selectivity of chelerythrine, its binding with both double-stranded and single-stranded DNA was further investigated by means of ESI-TOF-MS under the same conditions as those of G-quadruplex, since the binding of chelerythrine with double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides has been previously reported50. Two 27 nt oligodeoxynucleotides, d[(TTAGGG)2TTA(CCCTAA)2] and d[(TTAGGG)2TTAAAATTAGGGTTA] mutated from human telomeric sequence d[(TTAGGG)4TTA], were used to form double-stranded hairpin and single-stranded random coil DNA, respectively, in order to obtain similar mass spectrometric responses with oligodeoxynucleotides in the same length and close base components. Only 1:1 complexes were significantly observed for chelerythrine with double-stranded (Figure S6) and single-stranded (Figure S7) DNA, and corresponding RBA values were calculated (Table 1). As a result (Table 1), the relative binding constant of chelerythrine with RNA G-quadruplex was 6 and 12-fold tighter than that with double-stranded hairpin and single-stranded DNA, respectively. Its RBA value with DNA G-quadruplex was 2.5 and 5-fold stronger than that with double-stranded hairpin and single-stranded DNA, respectively. This indicated that chelerythrine possesses G-quadruplex specificity for human telomeric RNA and DNA G-quadruplexes.

Discussion

A study on binding of chelerythrine, an antitumor natural alkaloid, to human telomeric DNA and RNA G-quadruplex was carried out by using various analytical methods including DNA polymerase stop assay, UV-melting study, ESI-TOF-MS, fluorescent TO displacement assay and UV-Vis absorption spectrophotometry. This study showed that chelerythrine selectively binds to and stabilizes human telomeric K+-form DNA G-quadruplex which is considered to be a biologically significant DNA secondary structure, as evidenced from the appearance of a series of intensive concentration-dependent paused bands in PAGE gel, and increase of thermal stability of K+-form G-quadruplex by chelerythrine. In sharp contrast, chelerythrine does not show any significant stabilizing effect on the Na+-form DNA G-quadruplex under tested conditions. The selectivity of chelerythrine to K+-form G-quadruplex over Na+-form analogue is in agreement with that sanguinarine (sharing the same skeleton with chelerythrine) shows much larger binding affinity with K+-form G-quadruplex than with Na+-form analogue49. ESI-TOF-MS study showed that chelerythrine exhibited a comparable relative binding affinity to that of TMPyP4 tetrachloride, a well-known G-quadruplex binder, with human telomeric DNA G-quadruplex. Both 1:1 and 2:1 stoichiometries were observed for chelerythrine complexed with human telomeric both DNA and RNA G-quadruplexes. The relative binding affinity of chelerythrine with RNA G-quadruplex was greatly higher than that with DNA counterpart. The binding specificity of chelerythrine for RNA G-quadruplex over DNA analogue was further supported by the facts of 8 nm larger bathochromic shift and 34% more hypochromicity presented in the absorption spectra of chelerythrine when complexed with RNA G-quadruplex than with DNA counterpart. The stronger interaction of chelerythrine with RNA G-quadruplex may be due to the higher stability of RNA G-quadruplex in which the C2′-OH groups make a major contribution to the increased stability of the RNA G-quadruplex over equivalent DNA analogue28. Further study on chelerythrine binding to human telomeric double-stranded hairpin and single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides revealed that chelerythrine possesses binding specificity for human telomeric RNA/DNA G-quadruplex as evidenced from that its relative binding ability with four-stranded RNA/DNA G-quadruplexes are at least 2.5 and 5.0-fold stronger than those with both double-stranded and single-stranded DNA, respectively. In addition, chelerythrine was determined to bind to the human telomeric DNA/RNA G-quadruplex by the mode of end stacking on the basis of the fact that it displaces the TO positioned on the G-tetrad and the characteristic UV-Vis absorption spectral changes of bathochromic shifts (2 nm and 10 nm, respectively) and hypochromicities (39.4% and 73.4%, respectively) of chelerythrine with addition of DNA/RNA G-quadruplex, along with a series of complex peaks of chelerythrine and DNA/RNA G-quadruplex containing two NH4+ ions observed in ESI-TOF-MS spectra.

The stabilization of G-quadruplexes with small organic molecules gives rise to various effects on telomere functions, such as telomerase inhibition, shortening of telomere length, and inhibition of tumor cell growth51,52,53,54,55,56. The binding selectivity of chelerythrine to human telomeric K+-form DNA G-quadruplex over the Na+-form analogue, and binding specificity for human telomeric RNA G-quadruplex establish it as a promising candidate in the structure-based design and development of G-quadruplex specific ligands.

Methods

Materials

Oligodeoxynucleotides used in DNA polymerase stop assay and UV-melting experiments were purchased from FASMAC Co., Ltd. (Japan). Human telomeric DNA/RNA and all other DNA sequences used in ESI-TOF-MS and UV-Vis absorption experiments were bought from Invitrogen (Japan). The concentrations of single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides were determined from UV absorbance at 260 nm, supposing the molar extinction coefficients (ε) of A, T, G, and C to be 16,000, 9,600, 12,000, and 7,000 M−1cm−1, respectively. The DNA and RNA were annealed in 100 μM stock solutions in 100 mM KCl or NaCl or ammonium acetate solution, heating to 95°C for 5 minutes, then slowly cooling down to room temperature. The annealed solution were stored at 4°C for at least 24 hours before the use. The 5′ Texas red-labeled DNA primer and human telomeric template sequence in PAGE grade were obtained from JBioS Co., Ltd. (Japan) and dissolved in Milli Q water to be used without further purification. Acrylamide/bisacrylamide solution and ammonium persulfate were purchased from Bio-Rad, and N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine was purchased from Fisher. rTaq DNA polymerase and dNTPs were purchased from TaKaRa (Japan). Sequence marker kit was purchased from TOYOBO Co., Ltd. (Japan). TMPyP4 tetratosylate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA), and converted to the tetrachloride salt by an Amberlite® IRA-400 (Cl) ion exchange resin column43. Stock solutions of chelerythrine (10 mM) and TMPyP4 were made in either DMSO or Milli Q water. Further dilutions to working concentrations were made with Milli Q water immediately prior to usage.

DNA polymerase stop assay47

A reaction mixture of template DNA (0.15 μM) and 5′ Texas red-labeled 20-mer primer (0.1 μM) was heated to 95°C for 3 min in a Taq (TaKaRa) reaction buffer (pH 7.5, final concentration of 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl or 50 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2) and left to cool to ambient temperature over 30 min. The desired amount of chelerythrine (0, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10 and 30 μM) (TMPyP4 tetratosylate as a reference compound in the concentrations of 0, 0.1, 0.3, 1 and 3 μM) was added to the reaction mixture and kept at ambient temperature for 1 hour before the addition of polymerase. Then Taq polymerase and dNTPs were put into the reaction mixture, which was further incubated at 42°C for 30 min. The reactions were terminated by adding three-fold volume of ethanol-3 M sodium acetate mixture (30:1 V/V) and subsequently loaded on a 6% sequencing PAGE gel, then analyzed by a Hitachi SQ5500E automated sequencer. The sequence markers were prepared according to the TOYOBO sequence Protocol.

UV-melting study42,57

UV melting profiles of G-quadruplexes were measured at 295 nm using a UV-2700 spectrometer (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a Shimadzu TMSPC-8 temperature controller. Before measurement, DNA was annealed in 100 mM KCl or NaCl solution at 95°C for 5 min and cooled to room temperature, then incubated at 4°C overnight. The G-quadruplex DNA (5 μM) samples were heated from 4°C to 98°C with a heating rate of 1°C/min in the absence and presence of chelerythrine or TMPyP4 tetrachloride (10 and 30 μM for the K+-form and Na+-form G-quadruplex, respectively). Each absorbance profile of G-quadruplex at 295 nm was recorded using all the same substances except the DNA as a blank control. The melting temperature (Tm) was calculated by the median method from the average of three independent measurements.

CD spectroscopy47

CD spectra were recorded in a J-725 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Japan) equipped with a 1 cm path length quartz cuvette. CD spectra for the preformed DNA G-quadruplex (5 μM) were determined in the absence and presence of chelerythrine (25 μM) in either 100 mM KCl solution or 100 mM ammonium acetate solution between 200 and 400 nm at 25°C. A buffer blank correction was made for all spectra.

ESI-TOF-MS spectrometry43,58

All ESI-TOF-MS experiments were conducted on a Bruker maXis impact mass spectrometer in the negative mode with the same method as previously described43. The source parameters were set as follows: capillary voltage of +3500 V, nebulizer of 1.0 bar, dry gas flow of 4.0 L/min at 120°C, and end plate offset voltage of 500 V. The analyzer was operated at a background pressure of 5 × 10−7 mbar. The rate of sample injection into the mass spectrometer was 3 μL/min. The mixture of a final concentration of 10 μM chelerythrine (TMPyP4 tetrachloride43 as a reference DNA G-quadruplex binder) and 10 μM various nucleic acids in 40 mM ammonium acetate solution (pH 7.0) was directly injected into mass spectrometer. Each sample of nucleic acid-drug complex solution was prepared in triplicate. Each mass spectrum was an average of at least 50 scans. Data were analyzed with the software of Compass DataAnalysis. The oligonucleotide sequences are shown as follows:

human telomeric DNA (22 nt): d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] (M = 6966.6 Da)

human telomeric DNA (27 nt): d[(TTAGGG)4TTA] (M = 8496.6 Da)

double-stranded hairpin DNA: d[(TTAGGG)2TTA(CCCTTA)2] (M = 8273.1 Da)

single-stranded DNA: d[(TTAGGG)2TTAAAATTAGGGTTA] (M = 8447.0 Da)

human telomeric RNA: r[(UUAGGG)4UUA] (M = 8789.3 Da)

Fluorescent intercalator displacement assay45

Competitive triazole orange (TO) displacement experiments were carried out with chelerythrine on a Cary Elipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies) according to the method described in the literature45. Aliquots of the chelerythrine (2.0 × 10−4 M) solutions containing 22 nt DNA G-quadruplex d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] or 27 nt RNA G-quadruplex (0.25 × 10−6 M) and TO (0.5 × 10−6 M) were added into 400 μL solution of G-quadruplex (0.25 × 10−6 M) and TO (0.5 × 10−6 M) in 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH7.43) containing 100 mM KCl. This operation ensured that the concentrations of chelerythrine increased gradually from 0 to 0.40 and 0.80 μM, while the concentrations of DNA/RNA and TO were kept constant. An equilibrium period of 5 minute for constant stirring of the mixed solution was allowed before measuring each spectrum. The fluorescence spectra were recorded with an excitation wavelength at 501 nm at room temperature, and the fluorescence intensities of maximum emission of bound TO at 530 nm were used to calculate the percent fluorescence decrease induced by competitive binding of chelerythrine.

UV-Vis absorption spectrophotometry47,50

UV-Vis absorption spectra were recorded with a UV-2700 ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan) over the spectral range of 200–800 nm. Spectrophotometric titrations were carried out by keeping the concentration of chelerythrine constant while gradually increasing the RNA/DNA concentration. To a solution of chelerythrine (5 × 10−6 M, 700 μL) in 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.43) containing 100 mM KCl was added aliquots (0, 10 and 20 μL) of preformed RNA or DNA G-quadruplex (1.775 × 10−4 M) solution containing the same concentration of chelerythrine (5 × 10−6 M) in 100 mM KCl solution. An equilibrium period of 5 min for constant shaking of the mixed solution was allowed before measuring each spectrum. The UV-Vis absorption spectra of chelerythrine after each titration were determined by deducting the contribution of the added RNA/DNA. The absorption spectra of chelerythrine after 0 and 10 μL titration of RNA and DNA (2.5 × 10−6 M) were shown in Figure S5 for a clear comparison of spectral changes caused by two species of G-quadruplexes.

Author Contributions

Z.H.J., L.P.B. and K.N. designed experiments. L.P.B. and M.H. conducted experiments. L.P.B. and Z.H.J. analyzed data. L.P.B. and Z.H.J. wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Recognition of Chelerythrine to Human Telomeric DNA and RNA G-quadruplexes

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by Macao Science and Technology Development Fund, MSAR (039/2011/A2 to Z.H.J.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Blackburn E. H. Telomere states and cell fates. Nature 408, 53–56 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley C. B., Futcher A. B. & Greider C. W. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 345, 458–460 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn W. C. et al. Creation of human tumour cells with defined genetic elements. Nature 400, 464–468 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelland L. R. Overcoming the immortality of tumour cells by telomere and telomerase based cancer therapeutics--current status and future prospects. European Journal of Cancer 41, 971–979 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabelica V., Baker E. S., Teulade-Fichou M. P., De Pauw E. & Bowers M. T. Stabilization and structure of telomeric and c-myc region intramolecular G-quadruplexes: the role of central cations and small planar ligands. Journal of the American Chemical Society 129, 895–904 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy K. C. Telomere dynamics and telomerase activation in tumor progression: prospects for prognosis and therapy. Oncology Research 7, 121–130 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffi G., Tannahill D., McCafferty J. & Balasubramanian S. Quantitative visualization of DNA G-quadruplex structures in human cells. Nature Chemistry 5, 182–186 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam E. Y., Beraldi D., Tannahill D. & Balasubramanian S. G-quadruplex structures are stable and detectable in human genomic DNA. Nat Commun 4, 1796 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel R., Lohr F., Trantirek L. & Dotsch V. High-resolution insight into G-overhang architecture. Journal of the American Chemical Society 135, 2816–2824 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S., Bandaria J. N., Qureshi M. H., Yildiz A. & Balci H. G-quadruplex formation in telomeres enhances POT1/TPP1 protection against RPA binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111, 2990–2995 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaug A. J., Podell E. R. & Cech T. R. Human POT1 disrupts telomeric G-quadruplexes allowing telomerase extension in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, 10864–10869 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. E., Cao K., Ryvkin P., Wang L. S. & Johnson F. B. Altered gene expression in the Werner and Bloom syndromes is associated with sequences having G-quadruplex forming potential. Nucleic Acids Research 38, 1114–1122 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidle S. Human telomeric G-quadruplex: the current status of telomeric G-quadruplexes as therapeutic targets in human cancer. The FEBS Journal 277, 1118–1125 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. & Patel D. J. Solution structure of the human telomeric repeat d[AG3(T2AG3)3] G-tetraplex. Structure 1, 263–282 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrus A. et al. Human telomeric sequence forms a hybrid-type intramolecular G-quadruplex structure with mixed parallel/antiparallel strands in potassium solution. Nucleic Acids Research 34, 2723–2735 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J., Carver M., Punchihewa C., Jones R. A. & Yang D. Structure of the Hybrid-2 type intramolecular human telomeric G-quadruplex in K+ solution: insights into structure polymorphism of the human telomeric sequence. Nucleic Acids Research 35, 4927–4940 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu K. N., Phan A. T., Kuryavyi V., Lacroix L. & Patel D. J. Structure of the human telomere in K+ solution: an intramolecular (3 + 1) G-quadruplex scaffold. Journal of the American Chemical Society 128, 9963–9970 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzalin C. M., Reichenbach P., Khoriauli L., Giulotto E. & Lingner J. Telomeric repeat containing RNA and RNA surveillance factors at mammalian chromosome ends. Science 318, 798–801 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeftner S. & Blasco M. A. Developmentally regulated transcription of mammalian telomeres by DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II. Nature Cell Biology 10, 228–236 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavis M. et al. Mechanical unfolding of long human telomeric RNA (TERRA). Chemical Communications 49, 6397–6399 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horard B. & Gilson E. Telomeric RNA enters the game. Nature Cell Biology 10, 113–115 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redon S., Reichenbach P. & Lingner J. The non-coding RNA TERRA is a natural ligand and direct inhibitor of human telomerase. Nucleic Acids Research 38, 5797–5806 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeftner S. & Blasco M. A. A ‘higher order' of telomere regulation: telomere heterochromatin and telomeric RNAs. The EMBO Journal 28, 2323–2336 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martadinata H. & Phan A. T. Structure of human telomeric RNA (TERRA): stacking of two G-quadruplex blocks in K(+) solution. Biochemistry 52, 2176–2183 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Suzuki Y., Ito K. & Komiyama M. Telomeric repeat-containing RNA structure in living cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, 14579–14584 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martadinata H. & Phan A. T. Structure of propeller-type parallel-stranded RNA G-quadruplexes, formed by human telomeric RNA sequences in K+ solution. Journal of the American Chemical Society 131, 2570–2578 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Kaminaga K. & Komiyama M. G-quadruplex formation by human telomeric repeats-containing RNA in Na+ solution. Journal of the American Chemical Society 130, 11179–11184 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collie G. W., Haider S. M., Neidle S. & Parkinson G. N. A crystallographic and modelling study of a human telomeric RNA (TERRA) quadruplex. Nucleic Acids Research 38, 5569–5580 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmura S. J. et al. In vitro and in vivo activity of protein kinase C inhibitor chelerythrine chloride induces tumor cell toxicity and growth delay in vivo. Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 6, 737–742 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemeny-Beke A. et al. Apoptotic response of uveal melanoma cells upon treatment with chelidonine, sanguinarine and chelerythrine. Cancer Letters 237, 67–75 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malikova J., Zdarilova A., Hlobilkova A. & Ulrichova J. The effect of chelerythrine on cell growth, apoptosis, and cell cycle in human normal and cancer cells in comparison with sanguinarine. Cell Biology and Toxicology 22, 439–453 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X., Lin S. & Yuan G. Spectroscopic probing of recognition of the G-quadruplex in c-kit promoter by small-molecule natural products. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 50, 996–1001 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S X. J., Yang Q., Li Q., Zhou Q., Zhang X., Tang Y. & Xu G. Formation of Human Telomeric G-quadruplex Structures Induced by the Quaternary Benzophenanthridine Alkaloids: Sanguinarine, Nitidine, and Chelerythrine. Chinese J Chem 28, 771–780 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Han H., Hurley L. H. & Salazar M. A DNA polymerase stop assay for G-quadruplex-interactive compounds. Nucleic Acids Research 27, 537–542 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogoi S. & Xodo L. E. Enhanced G4-DNA binding of 5,10,15,20 (N-propyl-4-pyridyl) porphyrin (TPrPyP4): a comparative study with TMPyP4. Chemical Communications 46, 7364–7366 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck J. L., Colgrave M. L., Ralph S. F. & Sheil M. M. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry of oligonucleotide complexes with drugs, metals, and proteins. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 20, 61–87 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabelica V., De Pauw E. & Rosu F. Interaction between antitumor drugs and a double-stranded oligonucleotide studied by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 34, 1328–1337 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan K. X., Gross M. L. & Shibue T. Gas-phase stability of double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides and their noncovalent complexes with DNA-binding drugs as revealed by collisional activation in an ion trap. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 11, 450–457 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosu F., Gabelica V., Houssier C. & De Pauw E. Determination of affinity, stoichiometry and sequence selectivity of minor groove binder complexes with double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Nucleic Acids Research 30, e82 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. et al. Exploring the formation and recognition of an important G-quadruplex in a HIF1alpha promoter and its transcriptional inhibition by a benzo[c]phenanthridine derivative. Journal of the American Chemical Society 136, 2583–2591 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X., Zhang Q., Chen H., Zhou J. & Yuan G. ESI mass spectrometric exploration of selective recognition of G-quadruplex in c-myb oncogene promoter using a novel flexible cyclic polyamide. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 25, 684–691 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L. P. et al. Aminoglycosylation can enhance the G-quadruplex binding activity of epigallocatechin. Plos One 8, e53962 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L. P. et al. Mass spectrometric studies on effects of counter ions of TMPyP4 on binding to human telomeric DNA and RNA G-quadruplexes. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 406, 5455–5463 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allain C., Monchaud D. & Teulade-Fichou M. P. FRET templated by G-quadruplex DNA: a specific ternary interaction using an original pair of donor/acceptor partners. Journal of the American Chemical Society 128, 11890–11893 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monchaud D., Allain C. & Teulade-Fichou M. P. Development of a fluorescent intercalator displacement assay (G4-FID) for establishing quadruplex-DNA affinity and selectivity of putative ligands. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 16, 4842–4845 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosu F. et al. Selective interaction of ethidium derivatives with quadruplexes: an equilibrium dialysis and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analysis. Biochemistry 42, 10361–10371 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L. P., Hagihara M., Jiang Z. H. & Nakatani K. Ligand binding to tandem G quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. Chembiochem: a European Journal of Chemical Biology 9, 2583–2587 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzicalupi C., Ferraroni M., Bilia A. R., Scheggi F. & Gratteri P. The crystal structure of human telomeric DNA complexed with berberine: an interesting case of stacked ligand to G-tetrad ratio higher than 1:1. Nucleic Acids Research 41, 632–638 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessi I. et al. Spectroscopic, molecular modeling, and NMR-spectroscopic investigation of the binding mode of the natural alkaloids berberine and sanguinarine to human telomeric G-quadruplex DNA. ACS Chemical Biology 7, 1109–1119 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L. P., Zhao Z. Z., Cai Z. & Jiang Z. H. DNA-binding affinities and sequence selectivity of quaternary benzophenanthridine alkaloids sanguinarine, chelerythrine, and nitidine. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 14, 5439–5445 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidle S. & Parkinson G. Telomere maintenance as a target for anticancer drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 1, 383–393 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezler E. M., Bearss D. J. & Hurley L. H. Telomere inhibition and telomere disruption as processes for drug targeting. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 43, 359–379 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezler E. M. et al. Telomestatin and diseleno sapphyrin bind selectively to two different forms of the human telomeric G-quadruplex structure. Journal of the American Chemical Society 127, 9439–9447 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D. et al. Inhibition of human telomerase by a G-quadruplex-interactive compound. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 40, 2113–2116 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C., Wu L., Ren J., Xu Y. & Qu X. Targeting human telomeric higher-order DNA: dimeric G-quadruplex units serve as preferred binding site. Journal of the American Chemical Society 135, 18786–18789 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh S. J. et al. Inhibition of the hypoxia-inducible factor pathway by a G-quadruplex binding small molecule. Sci. Rep. 3, 2799 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L. P., Cai Z., Zhao Z. Z., Nakatani K. & Jiang Z. H. Site-specific binding of chelerythrine and sanguinarine to single pyrimidine bulges in hairpin DNA. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 392, 709–716 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H., Bai L. P. & Jiang Z. H. Synthesis and human telomeric G-quadruplex DNA-binding activity of glucosaminosides of shikonin/alkannin. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 22, 1582–1586 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Recognition of Chelerythrine to Human Telomeric DNA and RNA G-quadruplexes