Abstract

AIM: To overview the literature on pancreatic hydatid cyst (PHC) disease, a disease frequently misdiagnosed during preoperative radiologic investigation.

METHODS: PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, and Google databases were searched to identify articles related to PHC using the following keywords: hydatid cyst, hydatid disease, unusual location of hydatid cyst, hydatid cyst and pancreas, pancreatic hydatid cyst, and pancreatic echinococcosis. The search included letters to the editor, case reports, review articles, original articles, meeting presentations and abstracts that had been published between January 2010 and April 2014 without any restrictions on language, journal, or country. All articles identified and retrieved which contained adequate information on the study population (including patient age and sex) and disease and treatment related data (such as cyst size, cyst location, and clinical management) were included in the study; articles with insufficient demographic and clinical data were excluded. In addition, we evaluated a case of a 48-year-old female patient with PHC who was treated in our clinic.

RESULTS: A total of 58 patients, including our one new case, (age range: 4 to 70 years, mean ± SD: 31.4 ± 15.9 years) were included in the analysis. Twenty-nine of the patients were female, and 29 were male. The information about cyst location was available from studies involving 54 patients and indicated the following distribution of locations: pancreatic head (n = 21), pancreatic tail (n = 18), pancreatic body and tail (n = 8), pancreatic body (n = 5), pancreatic head and body (n = 1), and pancreatic neck (n = 1). Extra-pancreatic locations of hydatid cysts were reported in the studies involving 44 of the patients. Among these, no other focus than pancreas was detected in 32 of the patients (isolated cases) while 12 of the patients had hydatid cysts in extra-pancreatic sites (liver: n = 6, liver + spleen + peritoneum: n = 2, kidney: n = 1, liver + kidney: n = 1, kidney + peritoneum: n = 1 and liver + lung: n = 1). Serological information was available in the studies involving 40 patients, and 21 of those patients were serologically positive and 15 were serologically negative; the remaining 4 patients underwent no serological testing. Information about pancreatic cyst size was available in the studies involving 42 patients; the smallest cyst diameter reported was 26 mm and the largest cyst diameter reported was 180 mm (mean ± SD: 71.3 ± 36.1 mm). Complications were available in the studies of 16 patients and showed the following distribution: cystobiliary fistula (n = 4), cysto-pancreatic fistula (n = 4), pancreatitis (n = 6), and portal hypertension (n = 2). Postoperative follow-up data were available in the studies involving 48 patients and postoperative recurrence data in the studies of 51 patients; no cases of recurrence occurred in any patient for an average follow-up duration of 22.5 ± 23.1 (range: 2-120) mo. Only two cases were reported as having died on fourth (our new case) and fifteenth days respectively.

CONCLUSION: PHC is a parasitic infestation that is rare but can cause serious pancreato-biliary complications. Its preoperative diagnosis is challenging, as its radiologic findings are often mistaken for other cystic lesions of the pancreas.

Keywords: Echinococcosis, Hydatid cyst, Pancreas, Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Core tip: Hydatid disease is a zoonotic disease caused by the Echinococcus parasite, which belongs to the Taeniidae family of the Cestode class. Although hydatid cysts can be found in almost any tissue or organ of the human body, the liver, lung, spleen, and kidney are the most commonly affected. Pancreatic hydatid cyst (PHC) disease is rare, even in regions where hydatidosis is endemic. Yet, PHC disease is associated with severe complications, such as jaundice, cholangitis, and pancreatitis. These complications often develop as a result of fistulization of the cyst content into pancreato-biliary ducts or external compression of those ducts by the cyst.

INTRODUCTION

Hydatid disease, also known as echinococcal disease, is a zoonotic disease caused by the Echinococcus parasite belonging to the Taeniidae family of the Cestode class. Four different Echinococcus species have been defined as causative agents of hydatid disease in humans[1,2]. The most common species encountered in humans are the Echinococcus granulosus (E. granulosus), which causes cystic echinococcosis, and the Echinococcus multilocularis, which causes alveolar echinococcosis[1,2]. E. granulosus is responsible for 95% of the human hydatid cases reported. In the biological life cycle of hydatid disease, carnivores are the definitive hosts while herbivores are the intermediary hosts. Humans themselves have no role in the biological life cycle and are usually infected after inadvertent ingestion of Echinococcus eggs in canine feces[1,2]. The disease continues to be a major public health issue in many regions of the world where agriculture and stockbreeding are primary sources of income. Although hydatid cysts can localize to almost any tissue or organ of the human body, the liver (50%-77%), lung (15%-47%), spleen (0.5%-8%), and kidney (2%-4%) are the most commonly involved organs[2-5].

Pancreatic hydatid cyst (PHC) disease is rare, even in regions where hydatidosis is endemic[4-7]. While the reported incidences of PHC have varied in different studies, the rates are consistently below 1%. PHC may develop as a primary (involving the pancreas only) or secondary (with multiple organ involvement) disease[6]. Since hydatid cysts grow slowly, a considerable portion of affected patients may remain asymptomatic for years. In symptomatic patients, however, the symptoms are varied and depend on location, size, and position relative to neighboring organs[4]. The most serious complications in PHC disease are jaundice, cholangitis, and pancreatitis, all of which can develop as a result of fistulization of the cyst content into pancreato-biliary ducts or external compression of those ducts by the cyst. Clinical tools routinely used to diagnose PHC are ultrasonography (USG), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic ultasound (EUS), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and serological testing[4]. Despite the advanced radiological imaging instruments in use, though, it is not always easy to differentiate hydatid cysts from common cystic neoplasms of the pancreas[4,8]. Thus, hydatid cyst disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions, especially in patients living in endemic areas. In this study, we review the cases of PHC in the literature and present a new PHC patient who was treated at our clinic to provide a comprehensive discussion of this disease and its features relevant to diagnosis and management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The primary aim of this study was to review cases of PHC published in the literature within the last 4.5 years. To this end, a literature search was made of the PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, and Google databases using the keywords hydatid cyst, hydatid disease, unusual location of hydatid cyst, hydatid cyst and pancreas, pancreatic hydatid cyst, and pancreatic echinococcosis (alone or in different combinations). All identified abstracts, case reports, letters to the editor, review articles, original articles, and other documents were reviewed. No language filter was set and the review period was set from January 2010 to April 2014. Reference lists of the retrieved articles were also examined to identify citations that complied with our inclusion criteria. Corresponding authors of the articles were contacted by email to obtain more detailed information about the patients. Articles without an accessible full-text version or those providing insufficient information or insufficient data for comparison with other studies were excluded. A table (Table 1) was generated using the following information: publication year, country, and language; patient age, sex, and complaint; cyst location and size; results of serologic tests and radiologic examinations; surgical approach, intraoperative complications, postoperative medical management, recurrence, and follow-up (months). In addition, important notes from the studies were summarized in a single sentence.

Table 1.

Summary of demographic and clinic characteristics patients (n = 57) with pancreatic hydatid cyst published in the medical literature between January 2000 and April 2014

| Ref. | Year | Country | Language | Paper type | Case count | Age (yr) | Sex | Complaint/examination findings | Cyst location | Cyst size (mm) | Serology |

| Trigui et al[4] | 2013 | Tunisia | English | Article | 12 | 21 | F | Epigastric mass + epigastric pain | Tail | NS | NS |

| 13 | M | Epigastric pain + RUQ pain | Tail + Body | NS | NS | ||||||

| 15 | M | Jaundice + RUQ pain | Head | NS | NS | ||||||

| 26 | M | Epigastric pain | Head | NS | NS | ||||||

| 50 | F | Epigastric pain | Head | NS | NS | ||||||

| 37 | F | Jaundice + RUQ pain | Head | 25 | Negative | ||||||

| 8 | M | Jaundice + RUQ pain | Head | 83 × 76 | Positive | ||||||

| 26 | F | Pancreatitis + epigastric pain | TaİL + body | 40 | Positive | ||||||

| 61 | F | Epigastric pain | Tail | NS | Positive | ||||||

| 11 | F | Jaundice + RUQ pain | Head | NS | Negative | ||||||

| 16 | F | Epigastric pain | Body | NS | Positive | ||||||

| 11 | F | Jaundice + epigastric mass + RUQ pain | Head | 50 | NS | ||||||

| Yarlagadda et al[5] | 2013 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 43 | M | Epigastric mass | Tail | 180 × 170 | NS |

| Patil et al[6] | 2013 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 47 | M | Epigastric mass | Tail + Body | 100 × 80 | Positive |

| Kaushik et al[7] | 2013 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 18 | F | LUQ pain | Tail | 65 × 63 | NS |

| Baghbanian et al[8] | 2013 | Iran | English | Case Report | 1 | 46 | M | Epigastric pain + fever | Tail | 60 × 50 | NS |

| Gundes et al[9] | 2013 | Turkey | Turkish | Case Report | 2 | 24 | F | Back pain | NS | 70 | NS |

| 50 | F | Abdominal pain | Head | 50 | NS | ||||||

| Mandelia et al[10] | 2012 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 6 | M | Jaundice + fever + epigastric mass | Head | 54 × 41 | Not-done |

| Kushwaha et al[11] | 2012 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 40 | M | Epigastric mass + epigastric pain | Tail + Body | NS | Positive |

| Makni et al[12] | 2012 | Tunisia | English | Review | 1 | 38 | M | Abdominal pain + vomiting + nausea | Tail + Body | 100 × 90 | Positive |

| Karaman et al[13] | 2012 | Turkey | English | Case Report | 1 | 32 | M | Epigastric pain | Neck | 55 × 45 | Positive |

| Rayate et al[14] | 2012 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 30 | F | Abdominal pain | Tail | 62 × 57 | Positive |

| Suryawanshi et al[15] | 2011 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 20 | M | Epigastric mass + epigastric pain | Head | 80 × 80 | NS |

| Varshney et al[16] | 2011 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 35 | M | Abdominal pain + vomiting + nausea | Tail | NS | Positive |

| Somani et al[17] | 2011 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 30 | F | Epigastric mass + epigastric pain | Head | NS | NS |

| Masoodi et al[18] | 2011 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 45 | M | LUQ mass | Tail | 70 × 60 | Positive |

| Makni et al[19] | 2011 | Tunisia | English | Case Report | 1 | 30 | F | Epigastric mass + discomfort | Body | 80 | Positive |

| Bhat et al[20] | 2011 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 4 | F | Jaundice + epigastric mass | Head + Body | 150 × 100 | Negative |

| Cankorkmaz et al[21] | 2011 | Turkey | English | Case Report | 1 | 7 | F | Epigastric mass + weight loss | Tail + Body | 70 × 60 | Negative |

| Dalal et al[22] | 2011 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 48 | M | Epigastric fullness + fever | Tail | 80 × 50 | Not-done |

| Agrawal et al[23] | 2011 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 5 | F | Jaundice + abdominal pain | Head | 120 × 100 | NS |

| Küçükkartallar et al[24] | 2011 | Turkey | Turkish | Case Report | 1 | 48 | F | Abdominal pain | Head | 28 × 25 | Negative |

| Tavusbay et al[25] | 2011 | Turkey | English | Case Report | 1 | 50 | M | Abdominal mass | NS | NS | Positive |

| Derbel et al[26] | 2010 | Tunisia | English | Article | 7 | 25 | F | LUQ mass + LUQ pain | Tail | 60 | Negative |

| 19 | F | Epigastric mass + RUQ pain | Tail | 70 | Negative | ||||||

| 32 | F | Epigastric pain | Tail + body (two cyst) | 150 | Positive | ||||||

| 41 | M | LUQ mass + LUQ pain + fever | NS | 150 | Negative | ||||||

| 38 | M | Jaundice + epigastric pain | Head | 50 | Negative | ||||||

| 29 | M | Jaundice + epigastric mass | Head | 60 | Negative | ||||||

| 25 | F | LUQ pain + vomiting | Tail + Body | 90 | Positive | ||||||

| Bansal et al[27] | 2010 | India | English | Case Report | 1 | 30 | F | Jaundice + epigastric mass | Head | 80 × 60 | Not-done |

| Boubbou et al[28] | 2010 | Morocco | English | Case Report | 1 | 38 | M | Jaundice + epigastric pain | Head | NS | NS |

| Shah et al[29] | 2010 | India | English | Article | 6 | 46 | M | Epigastric pain | Tail | 28 | Positive |

| 37 | F | Epigastric mass + vomiting | Body | 26 | Positive | ||||||

| 18 | M | Dyspepsia | Body | 33 | Positive | ||||||

| 22 | F | Epigastric pain | Tail | 48 | Negative | ||||||

| 28 | M | Jaundice | Head | 50 | Positive | ||||||

| 68 | M | Jaundice | Head | 35 | Negative | ||||||

| Karakas et al[30] | 2010 | Turkey | English | Letter | 1 | 18 | M | Abdominal pain + fever | Body | 70 × 45 | Negative |

| Diop et al[31] | 2010 | France | English | Case Report | 1 | 29 | M | Acute pancreatitis | Tail | 35 × 25 | Positive |

| Szanto et al[32] | 2010 | Romania | English | Case Report | 1 | 49 | F | Epigastric pain + bloating + vomiting | Tail | NS | NS |

| Cağlayan et al[33] | 2010 | Turkey | English | Article | 1 | 70 | M | NS | NS | NS | Positive |

| Orug et al[34] | 2010 | Turkey | English | Case Report | 2 | 26 | M | Abdominal pain + fatique + vomiting | Tail | 115 × 95 | NS |

| 57 | F | Epigastric pain + weight loss | Tail | 45 × 35 | NS | ||||||

| Chammakhi-Jemli et al[35] | 2010 | Tunisia | French | Case Report | 1 | 32 | F | Acute pancreatitis + epigastric mass | Tail | 80 | Negative |

| Elmadi et al[36] | 2010 | Morocco | French | Case Report | 1 | 7 | M | Jaundice + fever + RUQ pain | Head | NS | Negative |

RUQ: Right upper quadrant; LUQ: Left upper quadrant; NS: Not-stated.

We also present a case of a 48-year-old woman with PHC who was treated at our clinic and who ultimately died after follow-up. The aim of this case presentation is to emphasize the grave consequences of benign hydatid cyst disease when undiagnosed by preoperative radiological examinations or not considered by a radiologist in differential diagnosis.

RESULTS

Literature review

A literature search using the above review criteria retrieved a total of 33 articles containing 57 cases about PHC disease[4-36]. Of these, 15 articles were from India, 8 from Turkey, 5 from Tunisia, 2 from Morocco, and 1 each from Iran, France and Romania. Twenty-two cases were reported from Tunisia, 20 from India, 10 from Turkey, 2 from Morocco, and 1 each from France, Iran and Romania. Twenty-nine articles were written in English, 2 in Turkish, and 2 in French. The current analysis, therefore, included a total of 58 patients (including our one new case), represented by 29 (50%) females and 29 (50%) males, aged 4 to 70 (mean ± SD: 31.4 ± 15.9) years. The age range of the males was 6 to 70 (mean ± SD: 33.4 ± 16.2) years and that of the females was 4 to 61 (mean ± SD: 29.4 ± 15.4) years. Cyst location in pancreas was reported for 54 patients, wherein the cyst was localized to the pancreatic head in 21 (38.8%), the pancreatic tail in 18 (33.3%), the pancreatic body and tail in 8 (14.8%), the pancreatic body in 5 (9.2%), the pancreatic head and body in 1, and the pancreatic neck in 1. Extra-pancreatic location of hydatid cysts was reported for 44 patients. Among these, 32 (72.7%) had no other foci other than pancreas (isolated) while the remaining 12 patients had extra-PHC as follows: liver, n = 6; liver + spleen + peritoneum, n = 2; kidney, n = 1; liver + kidney = 1; kidney + peritoneum = 1; and liver + lung, n = 1. Serological data were available from reports of 40 patients, of which 21 (54%) were serologically positive and 15 (38%) were serologically negative; the remaining 4 patients underwent no serological testing. Information about pancreatic cyst size was available for 42 patients; the smallest cyst diameter was 26 mm and the largest cyst diameter was 180 mm (mean ± SD: 71.3 ± 36.1 mm). Postoperative follow-up information was available for 48 patients and postoperative recurrence information for 51 patients. During the average follow-up duration of 22.5 ± 23.1 (range: 2-120) mo, none of the patients developed recurrence. Only two patients (our new case) died on postoperative day 4 and 15 respectively. Tables 1 and 2 provides detailed information regarding chief demographic data of the 57 patients included in the study.

Table 2.

Detailed information regarding chief demographic data of the 57 patients included in the study

| Ref. | Radiology | Surgical approach | Complication | Medical treatment | Recurrence | Follow-up (mo) | Other hydatid cyst focuses |

| Trigui et al[4] | NS | Distal pancreatectomy | No | NS | No | 24 | NS |

| USG + CT | Partial cystectomy + drainage | Hemorrhage | NS | No | 36 | Liver + spleen + peritoneum | |

| USG + CT | Partial cystectomy + drainage | Pancreatic fistula | NS | No | 24 | Liver | |

| USG + CT | Partial cystectomy + drainage | Cavity infection | NS | No | NS | Liver + lung | |

| USG + CT | Partial cystectomy + drainage | Pancreatic fistula | NS | No | 5 | No | |

| USG + CT | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | Hemorrhage | NS | No | 9 | NS | |

| USG + CT | Partial cystectomy + duodenal fistula treatment | No | NS | No | 24 | NS | |

| USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | No | NS | No | 36 | Liver | |

| USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | No | NS | No | 36 | NS | |

| USG + CT | Cysto-duodenal anastomosis | No | NS | No | NS | Liver | |

| USG + CT | Partial cystectomy + drainage | No | NS | No | 24 | NS | |

| USG + CT | Cysto-duodenal anastomosis | No | NS | No | NS | NS | |

| Yarlagadda et al[5] | USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | No | Albendazole-6 mo | No | 6 | No |

| Patil et al[6] | USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy | No | Albendazole-3 wk | No | 6 | No |

| Kaushik et al[7] | USG + CT | Total cystectomy + marsupialisation | No | Albendazole-3 wk | No | 6 | NS |

| 1Baghbanian et al[8] | USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy + necrozectomy + partial nephrectomy | Died (POD15) | No | Died | Died | Kidney |

| Gundes et al[9] | NS | Partial cystectomy + omentoplasty | Wound infection | Albendazole-4 mo | No | NS | NS |

| CT | Partial cystectomy + omentoplasty | Wound infection | Albendazole-4 mo | No | NS | No | |

| 2Mandelia et al[10] | USG + MRCP | Enucleation + cholangiography | No | Albendazole-3 wk | No | 24 | No |

| Kushwaha et al[11] | USG + CT | PAIR + epigastric cyst excision | Pancreatitis | Albendazole-3 mo | No | 6 | Kidney + peritoneum |

| Makni et al[12] | CT | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | No | Albendazole-3 mo | No | 8 | No |

| 3Karaman et al[13] | USG + CT | Percutaneous drainage | No | Albendazole-2 mo | No | 18 | No |

| Rayate et al[14] | USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy | No | Albendazole-2 mo | No | 7 | No |

| 4Suryawanshi et al[15] | USG + CT | Cyst evacuation + omentoplasty-laparoscopic | No | Albendazole-3 mo | No | 3 | No |

| 5Varshney et al[16] | CT | Distal pancreatectomy | No | Albendazole-3 wk | No | 10 | No |

| 6Somani et al[17] | USG + CT + ERCP | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | No | Albendazole-6 mo | NS | 6 | NS |

| 7Masoodi et al[18] | USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | Hyperglisemia? | Albendazole-1 mo | No | 6 | No |

| Makni et al[19] | USG | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | Pancreatic fistula | Albendazole-3 mo | No | 8 | No |

| Bhat et al[20] | USG + CT | Partial cystectomy + drainage | No | Albendazole-3 mo | No | 24 | No |

| 8Cankorkmaz et al[21] | USG + CT | Partial cystectomy + drainage | Pancreatic fistula | NS | No | 24 | No |

| 9Dalal et al[22] | USG + CT | Cyst excision along with tail of the pancreas | No | Albendazole-6 mo | No | 8 | No |

| 10Agrawal et al[23] | USG + MRCP | Enucleation + cholangiography + cholecystectomy + cystography | No | Albendazole-2 mo | NS | NS | NS |

| 11Küçükkartallar et al[24] | USG + CT + MRCP | Partial cystectomy + omentoplasty | No | Albendazole-4 mo | No | 10 | No |

| 12Tavusbay et al[25] | USG + CT | Partial cystectomy + omentoplasty + splenectomy + mesenteric cyst excision | Wound infection | Albendazole-6 mo | No | 12 | Liver + spleen + peritoneum |

| 13Derbel et al[26] | USG + CT | Partial cystectomy | No | No | No | 35 | No |

| USG + CT | Partial cystectomy (for all cysts) | No | Albendazole-6 mo | No | 9 | Liver (13 cyst) | |

| USG + CT | Partial cystectomy for both pancreatic cysts | No | No | No | 6 | No | |

| USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy | No | No | No | 9 | No | |

| USG + CT | Partial cystectomy (for all cyst) | Acute pancreatitis | Albendazole-6 mo | No | 14 | Liver | |

| USG + CT + MRI | Partial cystectomy | No | No | No | 16 | No | |

| USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | No | No | No | 2 | No | |

| 14Bansal et al[27] | USG + MRCP + EUS | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | No | Albendazole-6 wk | No | 6 | No |

| Boubbou et al[28] | USG + CT | PAIR + drainage + cystogastrostomy laparoscop | No | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Shah et al[29] | USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | No | Albendazole-6 wk | No | 120 | No |

| USG + CT | Central pancreatectomy + reconstruction | No | Albendazole-6 mo | No | 96 | No | |

| USG + CT + MRI | Pericystectomy | No | Albendazole-6 mo | No | 52 | No | |

| USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | No | Albendazole-6 wk | No | 50 | No | |

| USG + CT + MRI | Partial cystectomy + evacuation + T-tube drainage | No | Albendazole-6 mo | No | 30 | Liver | |

| USG + CT + MRI | Partial cystectomy + evacuation + T-tube drainage | No | Albendazole-6 mo | No | 4 | No | |

| 15Karakas et al[30] | USG + CT + MR | Distal pancreatectomy + cystectomy | Pancreatic fistula | NS | No | 4 | No |

| 16Diop et al[31] | CT + MR + EUS | Distal pancreatectomy + polar nephrectomy + partial cystectomy-Liver | No | Albendazole-18 mo | No | 48 | Liver + kidney |

| Szanto et al[32] | USG + CT + EUS | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | Hemoperitoneum | Not-used | No | NS | NS |

| Cağlayan et al[33] | NS | NS | NS | Albendazole | NS | NS | NS |

| Orug et al[34] | USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | No | Albendazole-6 mo | No | 24 | No |

| USG + CT | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | No | Albendazole-3 mo | No | 24 | No | |

| Chammakhi-Jemli et al[35] | USG + CT + MRI | Distal pancreatectomy + splenectomy | No | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Elmadi et al[36] | USG + MRI | Partial cystectomy + evacuation | No | NS | NS | 24 | No |

This patient arrived at the hospital with signs of acute pancreatitis. Despite tienam therapy, he developed renal dysfunction and pancreatic necrosis that affected 50% of the organ. Due to deterioration in his overall status, the patient underwent distal pancreatectomy + necrosectomy + partial nephrectomy (for renal hydatid cyst). Unfortunately, the patient was lost on postoperative day 15;

This patient was admitted to physician with episodes of obstructive jaundice and elevated liver function tests. Results from MRCP and US were both consistent with a choledocal cyst. An intraoperative cholangiography revealed normal bile flow;

This patient underwent percutaneous drainage after 12 d treatment with albendazole. A cystogram was done, and there was no relationship between cyst and pancreatic duct. The patient received albendazole for 2 mo after the operation. The serologic test was negative during follow-up;

This patient was tested for abdominal pain, leukocytosis, and hyperamylasemia and diagnosed with a pancreatic head cyst that compressed the duct externally. Subsequently, the patient developed acute pancreatitis secondary to ductus compression;

No differential diagnosis was made on CT. Therefore, a FNAC was performed and cytologic examination revealed hooklets of parasite. The patient was administered a 21 d course of albendazole at pre-operative and post-operative periods;

This patient developed jaundice 1 year ago and had elevated levels of AST and ALT. Findings from US, CT, and ERCP were consistent with a choledocal cyst. Thus, a stent was placed in the common bile duct, and a laparotomy operation was performed. After intraoperative exploration, the lesion was considered a cystadenoma. Whipple operation was performed since dissection of the cystic lesion was difficult;

The patient was administered albendazole for 4 d preoperatively and 1 mo postoperatively. Postoperative hyperglycemia developed as a complication and was treated with insulin;

A pancreatic pseudocyst was considered to exist, and a US-guided drainage was attempted. However, the cyst perforated into the peritoneal cavity during the procedure, and open surgery was performed and a pancreatic fistula developed. The drain was removed 18 d later;

Clinical presentation and CT findings of this patient were consistent with an abscess. A US-guided aspiration was performed, and he culture result was sterile. Although the patient was sent home on medical therapy, he was admitted to the hospital again with signs of intestinal obstruction. A hydatid cyst was initially diagnosed, and a US-guided cytology confirmed hydatidosis;

This patient was initially diagnosed with a choledocal cyst and underwent diagnostic laparoscopy. The cystic lesion originated from the pancreatic head and the aspirated fluid sample from the cyst clear fluid rather than bile. This finding indicated hydatid cyst, and an open operation was performed. Despite findings consistent with a pancreatic fistula on MRCP, no such relationship was detected in cytography. A cholangiography was carried out, and the fluid easily passed to duodenum;

MRCP images of this patient were consistent with a Type-II choledocal cyst;

This patient had two previous hepatic hydatid cyst surgeries. He had cysts in liver, spleen, pancreas, and the area below the incision. Albendazole treatment was begun 3 wk prior to the operation. The operation team performed splenectomy + total peritoneal cyst excision + partial cystectomy + omentoplasty for two cysts in liver;

The authors reported there was no relationship between hydatid cyst and common bile duct or pancreatic duct in any patient. Only 2 patients had bile duct dilatation secondary to compression of the common bile duct by hydatid cyst;

USG revealed dilatation in bile ducts. MRCP was consistent with a type-III choledocal cyst. EUS showed a mass lesion originating from the pancreatic head. Since its intraoperative resembled a cystic neoplasm, a Whipple procedure was carried out. Examination of the specimen revealed the relationship between cyst and pancreatic duct;

This patient had elevated liver function tests and increased blood amylase levels (acute pancreatitis) in preoperative testing. Radiologically, dilation of the pancreatic duct and enlargement of the pancreatic body were apparent. The patient received preoperative albendazole treatment. A fluid collection developed at the surgical area at the postoperative period, and a US-guided drainage catheter was placed. In addition, the pancreatic duct was stented, and external drainage dramatically improved after the stenting procedure;

A pancreatic cyst was diagnosed in an examination performed for pancreatitis. MR and EUS localized the fistula between the pancreatic duct and cyst. USG: Ultrasonography; CT: Computed tomography; MRCP: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; NS: Not-stated; FNAC: Fine needle aspiration cytology; US: Ultrasonography; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound.

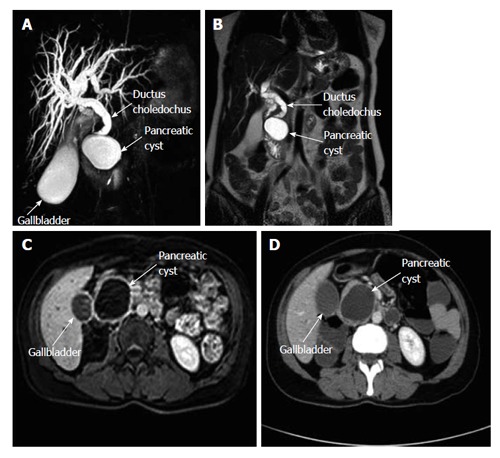

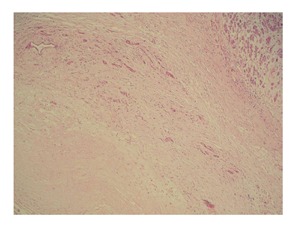

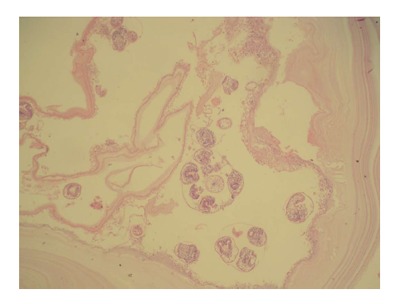

A 48-year-old woman presented to our outpatient clinic with malaise, fatigue, pruritus, yellowish discoloration of the eyes, darkening of urine color, and acholic gaita. She explained that her complaints, except for jaundice, had started 2 mo previous and the jaundice developed 15 d ago. On physical examination, her sclerae were icteric and whole body was jaundiced. Biochemical tests revealed the following results: aspartate aminotransferase (AST): 205 U/L; alanine aminotransferase (ALT): 673 U/L; total bilirubin: 11.6 mg/dL; direct bilirubin: 9.3 mg/dL; hemoglobin: 13 g/dL; platelet count: 244000/μL; white blood cell count: 5000/μL; carbohydrate antigen 19-9: 45 U/mL (normal range: 0-39). Ultrasonography showed that her gall bladder was hydropic and that the common bile duct and intrahepatic bile ducts were dilated. In addition, a 50 mm × 43 mm anechoic lesion consistent with choledococele was detected in the distal common bile duct. A MRCP was performed and showed a common bile duct diameter of 11 mm, dilated intrahepatic bile ducts, and a 4.5 cm mass in the pancreatic head, which appeared hyperintense on T2A imaging and caused stenosis in the distal tip of the common bile duct (Figure 1). An ERCP showed no intraluminal mass lesion. The consensus of a gastroenterologist and a radiologist was that this lesion could be a choledococele or duodenal diverticulum. Considering the above findings, a laparotomy was scheduled, in which the abdomen was entered via a midline incision followed by opening of the gastrocolic ligament and application of the Kocher maneuver. A mass lesion of 5 cm × 5 cm was observed in the pancreatic head, and appeared to be malignant. The common bile duct was markedly dilated. Based on preoperative tests and the intraoperative appearance of the pancreatic head, the mass was regarded as a malignant lesion, and a pancreaticoduodenectomy with pyloric preservation was performed without any intraoperative complications. On post-surgery day 1, the patient’s liver function tests were abnormal and her blood pressure dropped. Yet, radiological tests revealed no abnormalities. Since her blood pressure and pulse continued to deteriorate substantially, the patient was taken back to the operating room. During laparotomy, it was observed that all intestinal segments were filled with abundant blood. A regional exploration revealed a pulsatile bleeding focus from a location close to the Wirsung canal in the intestinal lumen. The bleeding was stopped, and the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Unfortunately, the profound coagulopathy that developed in the patient could not be reverted and she died on postoperative day 4. A detailed examination of the pathology specimen demonstrated that the mass had characteristics consistent with a hydatid cyst (Figures 2 and 3). In addition, areas of severe fibrosis were noted in regions neighboring the cyst.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography shows a hydropic gall bladder and dilated intrahepatic bile ducts and common bile duct. The distal portion of the common bile duct is narrowed due to external compression. A: A pancreatic cyst compressing the lower tip of the common bile duct is also seen in this section; B: A coronal T2-weighed MR cross-section shows a pancreatic cyst and a dilated common bile duct; C: Intravenous T1-weighed axial cross-section with contrast enhancement shows a pancreatic cyst; D: An axial computerized tomography cross-section with contrast enhancement shows a pancreatic cyst with a thick wall and without central contrast uptake. MR: Magnetic resonance.

Figure 2.

Patient’s mass has characteristics consistent with a hydatid cyst. The cyst wall is surrounded by fibrous capsule (also called the pericyst layer). The adjacent parenchyma demonstrates pressure atrophy (hematoxylin-Eosin stain ×100).

Figure 3.

Cyst wall of the patient’s mass consists of a laminated faintly stained chitinous membrane (outer layer). Multiple protoscolices are present within the daughter cyst (inner germinal layer, hematoxylin-Eosin stain × 100).

DISCUSSION

Humans have no biological role in the life cycle of hydatids, and they are inadvertently infected upon ingestion of Echinococcus eggs containing live oncospheres in canine feces. The ingested eggs first penetrate the intestinal wall, then pass to the portal system, and ultimately reside in hepatic sinusoids[3,7]. Larvae with a diameter less than 0.3 mm can escape the liver’s filtering system (first Lemman’s filter) and reach the lungs where they are entrapped by a second capillary filtering system (second Lemman’s filter). Larvae that escape the lung may then pass to any part of the human body via arterial circulation[1-3]. The organization of the filtering systems explain why hydatid cysts most commonly reside in the liver, with the second most common residence being the lung.

A number of hypotheses regarding the mode of passage of E. granulosus to pancreas have been postulated, the most accepted is the hematogenous dissemination discussed above[3,8,10-12,14,27]. The second route involves passage of cystic elements into the biliary system and then to the pancreatic canal and pancreas[3,10,14,27]. The third route involves passage of cystic elements into lymphatic channels through the intestinal mucosa and then to pancreatic tissue rich in lymphatic network[3,8,10-12,14,20,27]. The fourth route is direct passage of larvae into pancreatic tissue, bypassing the liver, via pancreatic veins[20]. The fifth, and final, hypothesized route is retroperitoneal dissemination[27,34]. In our literature review, an isolated PHC was detected in 72% and a secondary PHC was detected in 28% of 43 cases where medical data were available.

The PHC incidence varies by region, ranging from 0.1% to 2%[5,8,9,11,13,15,16,29]. Pancreatic cysts are solitary 90%-91% of the time, and their pancreatic distribution is heterogeneous[4,19,26]. According to data from the literature, 50%-58% of PHCs are found in the pancreatic head, 24%-34% in the pancreatic body, and 16%-19% in the pancreatic tail[4,5,12,19]. The rich vascular network found in the pancreatic head suggests that larvae reach this region via systemic circulation[4,26]. We did not find any significant difference in location prevalence between pancreatic head (38%) and pancreatic tail (34%). Prevalence of tail localization, however, may be even higher when cysts in the pancreatic body and tail are also taken into consideration.

Pancreatic cysts grow slowly (0.3-2 cm per year)[2], and some patients remain asymptomatic for years prior to obtaining a definitive diagnosis. Such patients are often incidentally diagnosed during tests performed for other indications. In symptomatic PHC patients, clinical presentation and complications depend on the location of the cyst within the pancreas[3-5,8,12,16,19]. Almost all cases we reviewed presented with epigastric pain, 20 had a palpable abdominal mass, and 15 had intermittent/permanent jaundice. Only a small proportion of patients suffered from non-specific symptoms such as fever, nausea-vomiting, weight loss, and abdominal fullness. PHC manifested itself as an intercostal herniation in only 1 patient[6]. However, we were unable to obtain precise information regarding duration of these symptoms.

Hydatid cysts located in the pancreatic head may cause obstructive jaundice or acute pancreatitis by either exerting external compression on or fistulizing into the common bile duct[4,10,12,15,20,23,26-30,31,35,36]. Less commonly, they may lead to cholangitis, duodenal stenosis, or duodenal fistula[4,20]. On occasion, hydatid cysts in the pancreatic head may remain silent but be palpable as an epigastric mass lesion. Hydatid cysts in the pancreatic body and tail usually remain asymptomatic until they grow large enough to compress adjacent organs or anatomical structures[4,8,16,20]. Gastric compression manifests as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and early satiety[4,20]. On rare occasions, splenic vein compression may lead to splenic vein thrombosis with severe complications such as left-sided portal hypertension[4,12,32,34]. A hydatid cyst may also become infected, causing an abscess, or an acute abdomen due to spontaneous intraperitoneal rupture[4,20]. Hydatid cyst may also at times erode walls of gastrointestinal luminal organs, causing a rupture into the lumen[4,20].

In this review, we found that 14 cases had bile duct dilatation due to external compression[4,10,20,23,26-30,36], while 4 had cysto-biliary fistula[4], 6 had pancreatitis due to external compression and fistulization (2 were necrotizing, and 4 were edematous)[8,12,15,30,31,35], 3 had pancreatic ductal dilatation[10,15,36], 4 had cysto-pancreatic fistula[12,27,30,31], 2 had left-sided portal hypertension[4,32], 1 had cysto-duodenal fistula[4], and 1 had splenic vein obstruction[34]. Some of these complications were detected by preoperative radiological examinations, and others were only detected at the time of surgery.

Radiological and clinical properties of the cases in this review suggest that a significant portion were characterized by cyst-induced compression of or fistulization into the pancreato-biliary system. However, the rate of this complication was far below the expected rate. Analysis of patients’ blood tests showed that 8 patients had elevated bilirubin (2.9-11.7 mg/dL), 9 had elevated ALP (280-1843 U/L), 7 had elevated ALT (56-335 U/L), 7 had elevated AST (72-235 U/L), 7 had elevated amylase (610-4965 U/L), and 2 had elevated lipase (103-1390 U/L)[5,8,10,12,15,17,20,21,23,26,27,29,30,36].

The first and most important step in the diagnosis of PHC is clinical suspicion. Important clues include residence in an endemic region or a previous hydatid cyst surgery. These clues may increase diasnostic yield when assessed in conjunction with results from radiological studies and serological tests. For diagnosis of pancreatic cysts, the most commonly performed radiologic tests are, in descending order, USG, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Complicated cases that require further workup are examined with invasive diagnostic tools, such as EUS and ERCP[26]. USG is a noninvasive, low-cost and sensitive diagnostic instrument. Gharbi defined the typical appearance of hydatid cysts in USG[12], but application of USG to pancreatic cysts is lower than for liver cysts because of the retroperitoneal location of the pancreas and bowel gas. CT is usually successful in delineating cyst size, location, relation with pancreato-biliary system, and presence of cysts in other organs. It is also successfully used for treatment monitorization and postoperative recurrence detection[12]. MRI and MRCP are particularly useful to delineate the relationship between cysts and pancreatic and bile ducts[12,31]. However, results from these techniques may be insufficient when attempting to differentiate between cysts located at the pancreatic head and those located at the common bile duct[10,27]. In MRI, superposition of the hydatid cyst with the pancreatic duct can be misinterpreted as a fistula[23]. To demonstrate the relationship between cyst and pancreatic duct and to differentiate cysts of unknown nature, ERCP can be used. ERCP is appropriate for palliative stent applications in cases with cholangitis or pancreatitis secondary to biliary or pancreatic duct obstruction[17,26]. It is also very beneficial in non-operative management of cases that developed biliary or pancreatic fistulae[12,30]. EUS is not commonly used[31,32], but it is capable of delineating pancreato-biliary system anatomy and taking biopsy samples when necessary. It can accurately show the relationship between the cyst and pancreatic duct[12,31]. Cystography during surgery is especially helpful to demonstrate the relationship of the cyst with the pancreato-biliary ducts and gastrointestinal tract[23]. In complicated cases, the gall bladder and common bile duct can be entered with a needle and a cholangiogram can be taken[10,20,29], which may show both the anatomy of bile ducts and their relationship with cyst[12].

For diagnosis, screening, and recurrence monitoring, the following serological tests are used: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, indirect hemagglutination, serum immunelectrophoresis, complement fixation test, and immunofluorescence assay[17,21,28]. The seropositivity rate is higher in hepatic hydatid cysts than cysts in other organs. We calculated a rate of 54% for PHC cases. It should be noted, however, that seronegativity does not guarantee absence of hydatid disease[26].

The differential diagnosis of PHCs include neoplastic (cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma, gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, vasculary tumors, metastatic cystic lesions) or non-neoplastic (congenital pancreatic cysts, pseudocysts) cystic lesions[16,19,27]. Diagnosis of cysts that cannot be made using noninvasive techniques can be made by taking either a biopsy from the lesion or an aspiration cytology sample from cyst fluid via percutaneous or endo-ultrasonographic techniques[4,18,26]. Using percutaneous fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) for the differential diagnosis of cystic pancreatic lesion, Varshney et al[16] showed hooklets of hydatid cyst cytologically. In contrast, Dalal et al[22] had to perform FNAC twice in order to diagnose hydatid cyst. Anaphylaxis and pouring of cyst content into the abdominal cavity are potential complications of the FNAC procedure. Hence, prophylactic antihelminthic agents should be started when FNAC is contemplated in a patient with suspected cysts; otherwise, the procedure should be avoided[4].

All patients presented in this review underwent at least one preoperative radiological or serological test. After these tests, 20 patients were diagnosed with PHC, 14 with benign/neoplastic cystic lesion of pancreas, 8 with choledocal cyst, 4 with PHC/cystic neoplasm of pancreas, 2 with hepatic hydatid cyst, and one with splenic hydatid cyst. Minimally invasive surgery was contemplated. No presumptive diagnoses were made for the remaining patients. As seen, only 40%-49% of patients were diagnosed with PHC at the preoperative period. This is true even for the most recent studies performed within the last 4.5 years. Diagnostically, the situation was even worse several decades ago, when the rate of preoperative PHC was far below 30%.

PHC can be treated with one or a combination of several therapies, including open or laparoscopic surgical approach, minimally invasive approach [puncture-aspiration-injection-reaspiration (PAIR) or direct percutaneous catheterization], and medical therapy[9]. As is the case for other organ hydatid cysts, open surgery is the gold standard for the treatment of PHC disease. Selection of the appropriate management approach is affected by many factors, such as surgeon’s experience, patient age, presence of comorbid conditions, pancreatic localization of cyst(s), cyst size, and relation of cyst to adjacent structures or the pancreatic and common bile ducts[4,29,31].

Pancreatic head cysts with no communication with biliary or pancreatic ducts can be managed with partial cystectomy + external drainage, partial cystectomy + omentopexy and pericystectomy, marsupialisation, and pancreaticoduodenectomy procedures[4,29,34]. Each method has its own advantages and disadvantages. In order to avoid postoperative pancreatic fistula formation, cysts with communication with the pancreatic duct can be treated with cysto-jejunal, cysto-duodenal, or cysto-gastric anastomosis techniques[4,26]. In cysts located in the pancreatic body or tail, the most appropriate approach is a spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy[4,26]. In cases where the spleen cannot be preserved, pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccinations should be done immediately to avert postsplenectomy complications[5]. Central pancreatectomy may be preferable when cysts are localized to the pancreatic body or neck[29]. The main advantage of this method is the preservation of pancreatic tissue and the minimization of complications, such as diabetes or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency[29]. Masoodi et al[18] reported in a patient that underwent a distal pancreatectomy hyperglycemia high enough to require insulin injection. For management of hydatid cysts of the pancreatic head, the role of pancreaticoduodenectomy is very limited[20]. Pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed in only 3 of 19 pancreatic head cysts[4,17,27]. A whipple procedure was applied in all three of these cases since the results of preoperative radiological examination and/or intraoperative findings were consistent with a cystic lesion of the pancreatic head. In our case, we experienced similar difficulties. While the preoperative tests, including CT, MRCP, and ERCP, were consistent with a choledocal cyst, the intraoperative appearance was totally compatible with a mass in the pancreatic head. Unfortunately, our patient was lost to a misfortunate complication. In retrospect, we realize that patient outcome may have been improved if the diagnosis was made preoperatively and simple partial cystectomy and drainage was performed intraoperatively. Hence, our main objective for writing this manuscript was to heighten awareness about this topic.

Although rarely reported in the literature, there are some studies describing percutaneous drainage of pancreatic hydatic cysts[10,13]. Percutaneous drainage can be accomplished by puncture, aspiration, injection of hypertonic saline solution, and re-aspiration of cyst content (PAIR) or direct catheterization of the cyst[13,18,28]. These procedures should be specifically carried out in Type I and II PHCs, cysts with a diameter less than 50 mm, patients who refuse surgery, and cases with a higher anesthesia risk[1]. The main advantage of PAIR is the ability to show scoleces in the aspirated cyst fluid cytopathologically within a short period of time. Another advantage is the ability to delineate the relative location of the cyst with the pancreatic duct by contrast material administration during the procedure. However, an unconscious percutaneous drainage procedure or one that is performed without estimating the possible presence of PHC may lead to cyst perforation and surgical complications[21]. The risk associated with release of cyst contents into abdominal cavity is markedly lower with a PAIR procedure that is carried out by passing through parenchyma of solid organs like liver and spleen than it would be with pancreatic and other intraabdominal cysts[26]. In cases where minimally invasive surgical therapy has been contemplated, antihelminthic therapy should be administered before (≥ 4 d) and after (≥ 3-4 wk) the procedure in order to reduce intracystic pressure and prevent anaphylaxis[1].

Although there are numerous articles about laparoscopic excision of hydatid cysts in other organs, there are only a few case reports on the use of the laparoscopic approach for PHCs. In one report, content of a cyst located in the pancreatic head was emptied by directly inserting a 10 mm trochar into the cyst followed by omentoplasty[15]. In our opinion, in order to apply this technique to PHCs, the preoperative diagnosis should be accurately made, the cyst must have an adequate neck, and the surgeon must be experienced in laparoscopy.

Antihelminthic prophylactic therapy (albendazole, mebendazole, or praziquantel) must be administered for 2-4 wk prior to surgery (open, laparoscopic, or PAIR) in order to decrease intracystic pressure and reduce anaphylaxis and postoperative recurrence risks. With radical resections that do not open the cyst cavity, there is no need for medical therapy afterwards[32]. One of the cyclic or continuous medical therapy protocols, however, should be applied during the postoperative period to patients who underwent conservative surgery. During follow-up, these asymptomatic cysts can be followed with medical therapy alone or their size assessed at yearly intervals.

Complications of PHC surgery can be divided into short- and long-term complications. Short-term complications or early postoperative complications include pancreatic fistula, biliary fistula, biloma, intraabdominal abscess, and wound infection. The most suitable approach for treating biloma and intraabdominal abscesses is percutaneous drainage. For biliary and pancreatic fistulae, daily output guides management decisions. ERCP shows well the location of the fistula and the presence of any obstruction due to cystic elements in pancreatobiliary ducts (distal to fistula). Simultaneously, therapeutic procedures like sphincterotomy and/or stent implantation can also be performed with ERCP. Use of somatostatin analogues may hasten closure and reduce output of pancreatic fistulae[19,21]. Surgical intervention is rarely needed, and intraoperative cholangiography or cystography may be performed to avoid such complications. In addition, planning surgery in line with cyst location may avert complications. The major long-term complication of cyst surgery is hydatid cyst recurrence. Recurrence is rather common after conservative surgical operations but almost never seen after radical surgery. Recurrence rates can be minimized by applying intraoperative protective measures, which are commonly applied in hepatic hydatid cyst surgery, or by administering preoperative or postoperative medical therapy.

In conclusion, PHC is a rare parasitic infestation that can cause serious pancreato-biliary complications. Despite advances in radiological instrumentation, preoperative diagnosis of PHC remains a challenge, and it is often misdiagnosed as other cystic diseases of the pancreas and distal choledocal cysts. Conservative surgical techniques, which are preferred over radical surgical interventions, should be applied, especially in cysts located in the pancreatic head. After confirmation of the diagnosis, cystography is a suitable method to demonstrate the relationship between the cyst and pancreatic duct. While postoperative antihelminthic therapy is not necessary in surgical operations that do not open the cyst cavity, a medical therapy lasting for 3-4 wk is appropriate after more conservative surgical procedures such as partial cystectomy.

COMMENTS

Background

Pancreatic hydatid cyst disease is rare but can lead to serious pancreato-biliary complications if left untreated. Despite advances in radiological techniques, preoperative diagnosis of panceatic hydatid cyst remains challenging, and it is frequently misdiagnosed preoperatively as other cystic diseases of the pancreas and distal choledocal cysts.

Research frontiers

The authors analyzed previously published articles regarding pancreatic hydatid cyst. For this purpose, a literature search was performed in PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, and Google databases using different keywords related to pancreatic hydatid cyst. Second, the authors presented a case of a 48-year-old female patient who underwent surgical treatment for pancreatic head hydatid cyst.

Innovations and breakthroughs

A review of the literature and personal experience suggest that pancreatic hydatid cyst disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions, especially in patients living in endemic areas.

Peer review

Echinococcosis is listed as one of World Health Organizations Neglected Zoonotic Diseases bringing a significant socioeconomic burden, mainly in impoverished and rural areas. The topic of this review is relevant although if performed in a systematic way it would have delivered a stronger evidence-based article for the medical community. Without bringing any new findings, this review stands out over previous attempts as it properly describes the methodology behind the searching and selection process of retrieving articles and represents a comprehensive source of information of reported cases in the last 4.5 years.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Elpek GO, Ghartimagar D, Nigro L, Otero-Abad B S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

References

- 1.Akbulut S, Sogutcu N, Eris C. Hydatid disease of the spleen: single-center experience and a brief literature review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1784–1795. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eris C, Akbulut S, Yildiz MK, Abuoglu H, Odabasi M, Ozkan E, Atalay S, Gunay E. Surgical approach to splenic hydatid cyst: single center experience. Int Surg. 2013;98:346–353. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00138.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wani RA, Wani I, Malik AA, Parray FQ, Wani AA, Dar AM. Hydatid disease at unusual sites. Int J Case Reposts Images. 2012;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trigui A, Rejab H, Guirat A, Mizouni A, Amar MB, Mzali R, Beyrouti MI. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas About 12 cases. Ann Ital Chir. 2013;84:165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yarlagadda P, Yenigalla BM, Penmethsa U, Myneni RB. Primary pancreatic echinococcosis. Trop Parasitol. 2013;3:151–154. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.122147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patil DS, Jadhav KV, Ahire PP, Patil SR, Shaikh TA, Bakhshi GD. Pancreatic hydatid presenting as an intercostal hernia. Int Jou Medical and applied Sciences. 2013;2:255–258. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaushik K, Garg P, Aggarwal S, Narang A, Verma S, Singh J, Singh Rathee V, Ranga H, Yadav S. Isolated Pancreatic Tail Hydatid Cyst - Is Distal Pancretectomy Always Required? Internet J Gastroenterol. 2013:13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baghbanian M, Salmanroghani H, Karegar S, Binesh F, Baghbanian A. Pancreatic Tail Hydatid Cyst as a Rare Cause for Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Case Report. Govaresh. 2013;18:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gundes E, Kucukkartallar T, Cakir M, Aksoy F, Bal A, Kartal A. Primary intra-abdominal hydatid cyst cases with extra-hepatic localization. JCEI. 2013;4:175–179. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandelia A, Wahal A, Solanki S, Srinivas M, Bhatnagar V. Pancreatic hydatid cyst masquerading as a choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:e41–e44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushwaha JK, Sonkar AA, Verma AK, Pandey SK. Primary disseminated extrahepatic abdominal hydatid cyst: a rare disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:pii: bcr0220125808. doi: 10.1136/bcr.02.2012.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makni A, Jouini M, Kacem M, Safta ZB. Acute pancreatitis due to pancreatic hydatid cyst: a case report and review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2012;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karaman B, Battal B, Ustunsoz B, Ugurel MS. Percutaneous treatment of a primary pancreatic hydatid cyst using a catheterization technique. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13:232–236. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2012.13.2.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rayate A, Prabhu R, Kantharia C, Supe A. Isolated pancreatic hydatid cyst: Preoperative prediction on contrast-enhanced computed tomography case report and review of literature. Med J DY Patil Univ. 2012;5:66–68. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suryawanshi P, Khan AQ, Jatal S. Primary hydatid cyst of pancreas with acute pancreatitis. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2011;2:122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varshney M, Shahid M, Maheshwari V, Siddiqui MA, Alam K, Mubeen A, Gaur K. Hydatid cyst in tail of pancreas. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:pii: bcr0320114027. doi: 10.1136/bcr.03.2011.4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Somani K, Desai AA. An unusual case of pancreatic hydatid cyst mimicking choledochal cyst. BHJ. 2011:53: 103–105. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masoodi MI, Nabi G, Kumar R, Lone MA, Khan BA, Naseer Al Sayari K. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas: a case report and brief review. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2011;22:430–432. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2011.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makni A, Chebbi Fi Jouini M, Kacem M, Safta ZB. Left pancreatectomy for primary hydatid cyst of the body of pancreas. J Afr Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;5:310–12 [DOOI: 10.1007/s12157-011-0305-z]. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhat NA, Rashid KA, Wani I, Wani S, Syeed A. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas mimicking choledochal cyst. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;31:536–538. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.84638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cankorkmaz L, Gümüş C, Celiksöz A, Köylüoğlu G. Primary hydatid disease of the pancreas mimicking pancreatic pseudo-cyst in a child: case report and review of the literature. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2011;35:50–52. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2011.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalal U, Dalal AK, Singal R, Naredi B, Gupta S. Primary hydatid cyst masquerading as pseudocyst of the pancreas with concomitant small gut obstruction--an unusual presentation. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011;27:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal S, Parag P. Hydatid cyst of head of pancreas mimicking choledochal cyst. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:pii: bcr0420114087. doi: 10.1136/bcr.04.2011.4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Küçükkartallar T, Cakır M, Tekin A, Özalp AH, Yıldırım MA, Aksoy F. [Primary pancreatic hydatid cyst resembling a pseudocyst] Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2011;35:214–216. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2011.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tavusbay C, Gur OS, Durak E, Haciyanli M, Genc H. Hydatid cyst in abdominal incisional hernia. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2011;112:287–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Derbel F, Zidi MK, Mtimet A. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas: A report on seven cases. AJG. 2010;11:219–222. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bansal VK, Misra MC, Krishna A, Kumar S, Garg P, Khan RN, Loli A, Jindal V. Pancreatic hydatid cyst masquerading as cystic neoplasm of pancreas. Trop Gastroenterol. 2010;31:335–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boubbou M, Boujraf S, Sqalli NH. Large pancreatic hydatid cyst presenting with obstructive jaundice. AJG. 2010;11:47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah OJ, Robbani I, Zargar SA, Yattoo GN, Shah P, Ali S, Javaid G, Shah A, Khan BA. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas. An experience with six cases. JOP. 2010;11:575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karakas E, Tuna Y, Basar O, Koklu S. Primary pancreatic hydatid disease associated with acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010;9:441–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diop SP, Costi R, Le Bian A, Carloni A, Meduri B, Smadja C. Acute pancreatitis associated with a pancreatic hydatid cyst: understanding the mechanism by EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1312–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szanto P, Goian I, Al Hajjar N, Badea R, Seicean A, Manciula D, Serban A. Hydatid cyst of the pancreas causing portal hypertension. Maedica (Buchar) 2010;5:139–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cağlayan K, Celik A, Koç A, Kutluk AC, Altinli E, Celik AS, Köksal N. Unusual locations of hydatid disease: diagnostic and surgical management of a case series. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2010;11:349–353. doi: 10.1089/sur.2009.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orug T, Akdogan M, Atalay F, Sakarogulları Z. Primary Hydatid Disease of Pancreas Mimicking Cystic Pancreatic Neoplasm: Report of Two Cases. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2010;30:2057–2060. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chammakhi-Jemli C, Mekaouer S, Miaoui A, Daghfous A, Mzabi H, Cherif A, Daghfous MH. [Hydatid cyst of the pancreas presenting with acute pancreatitis] J Radiol. 2010;91:797–799. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(10)70117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elmadi A, Khattala K, Elbouazzaoui A, Rami M. [Acute cholangitis revealing a primary pancreatic hydatid cyst in a child] J de pediatrie et de puericulture. 2010;23:201–203. [Google Scholar]