Abstract

Objective

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is the most common malignancy in a Northeast Thai population. Smoking and alcohol drinking are associated with the production of free radical intermediates, which can cause several types of DNA lesions. Reduced repair of these DNA lesions would constitute an important risk factor for cancer development. We therefore examined whether polymorphisms in DNA base-excision repair (BER) genes, XRCC1 G399A and OGG1 C326G, were associated with CCA risk and whether they modified the effect of smoking and alcohol drinking in the Thai population.

Design

A nested case–control study within the cohort study was conducted: 219 participants with primary CCA were each matched with two non-cancer controls from the same cohort on sex, age at recruitment and the presence/absence of Opisthorchis viverrini eggs in stools. Smoking and alcohol consumption were assessed on recruitment. Polymorphisms in BER genes were analysed using a PCR with high-resolution melting analysis. The associations were assessed using conditional logistic regression.

Results

Our results suggest that, in the Thai population, polymorphisms in XRCC1 and OGG1 genes, particularly in combination, are associated with increased susceptibility to CCA, and that their role as modifiers of the effect of smoking and alcohol consumption influences the risk of CCA.

Conclusions

Better ways of reducing habitual smoking and alcohol consumption, targeted towards subgroups which are genetically susceptible, are recommended. CCA is a multifactorial disease, and a comprehensive approach is needed for its effective prevention. This approach would also have the additional advantage of reducing the onset of other cancers.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This was a nested case–control study within the cohort study. This design has the advantage of minimising a systematic recall bias which can occur when the receipt of diagnosis of cancer leads to participants modifying their self-reported personal histories, in this case, their recall of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption. This was prevented in the present study because participants were interviewed at the time of recruitment, before case or control status was defined.

The diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma was not histologically confirmed in all the cases.

This study did not include the population aged 70 years and above.

In future research, larger samples are needed to increase the power of the studies.

Introduction

The data from GLOBOCAN 2008 show that liver cancer is the fourth most common cause of death from cancer worldwide.1 It is the most common cancer in Northeast Thailand, where the great majority of cases are cholangiocarcinomas (CCA).2 Data from the Khon Kaen Cancer Registry (KKCR) have shown that the estimated age-standardised incidence rates for men and women are 84.6 and 36.8 per 100 000, respectively.3

Among several types of DNA damage induced by carcinogens from tobacco and alcohol are oxidative base damage and single-stand breaks, which are repaired by the base-excision repair (BER) pathway.4 Genetic variants and polymorphisms in DNA repair pathways have been reported to affect the levels of DNA lesions, which accumulate in the epithelial tissue of the hepatobiliary tract system, thus influencing the susceptibility to biliary tract cancers and stones in a Chinese population5 6 and gall bladder cancer in an Indian population.7 There were very few studies on this topic in relation to CCA in the Thai population, but there have been studies which clarify the role of the accumulation of levels of oxidative DNA lesions in patients with liver fluke infections and patients with CCA8–10; these studies concluded that some biomarkers from oxidative DNA lesions induced by liver fluke infection, a major risk factor, may play an important role in CCA development. However, the results from our previous study showed that not only liver fluke infection but also certain lifestyle and dietary cofactors were associated with increased risk of CCA.11 12 Long-term smoking13 14 and alcohol drinking4 15 16 are associated with the production of free radical intermediates, which can cause several kinds of DNA lesions. Reduced repair of these DNA lesions would constitute an important risk factor for cancer development. With respect to genetic factors, a number of polymorphisms in various DNA repair genes have been discovered, and it is possible that these polymorphisms may affect DNA repair capacity and thus modulate susceptibility to cancer. Investigations are therefore needed into the different patterns of smoking and alcohol drinking in relation to susceptibility to CCA, along with DNA repair capacity induced by genetic variations or polymorphisms.

Although cigarette smoking was not associated with CCA development in the previous studies conducted in Thailand12 17–20 and elsewhere,21 a modifying effect by DNA repair genes remains a possibility. With respect to the use of alcohol, this was related to a substantially increased risk of CCA in our previous study.12 At the molecular level, it is known that single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes participate biochemically in the BER pathway (X-ray repair cross-complementing group 1: XRCC1 and 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1: OGG1), which repairs smoking-induced and alcohol-induced oxidative DNA base modifications.4

In this study, we therefore investigated whether polymorphisms in the DNA BER genes (XRCC1 G399A and OGG1 C326G) are associated with CCA risk and whether their effects are modified by cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking in a Northeastern Thai population residing in a high-incidence area of opisthorchiasis-related CCA. The selection of these SNPs in DNA BER genes was based on their putative effect on protein function and/or previous evidence of associations with the risk of hepatobiliary tract cancers in the Asian (Chinese and Indian) populations5–7and the combined effects of a DNA-repair gene and metabolic gene polymorphisms on CCA risk in Thailand.10 However, these studies involved only gene–gene interaction. There is a need for studies of gene–environment interactions, especially between DNA-repair genes and exposure to the carcinogenic effects of tobacco/alcohol carcinogens in relation to CCA risk.

Materials and methods

Study participants

This was a case–control study nested within the 23 584 participants of the Khon Kaen Cohort Study (KKCS). Details of the KKCS and the selection of CCA cases and controls used in this study have been previously reported.11 12 22 Briefly, 219 (0.9%) cohort members who had developed a primary CCA diagnosis, at least by ultrasound, with or without contrast radiology, tumour markers (such as CA19–9) or histopathology, six or more months after enrolment were identified. The vital status and date of death of potential cases were ascertained by linkage to the files of deaths in Thailand, which are held in the database of the National Health Security Office and the demographic database of the Ministry of the Interior. All cases had died within 2 years of diagnosis. Two non-cancer controls from the same cohort population were randomly selected for matching with each case on sex, age at recruitment (±3 years) and the presence/absence of liver fluke eggs in the faeces at recruitment (detected by the formalin ethyl acetate concentration technique).

Assessment of cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking

Definitions of alcohol use, cigarette smoking and levels of consumption of alcohol were the same as those previously described.12 A smoker was defined as someone who had ever smoked any type of cigarette on a daily basis. However, in this study, smokers were categorised into four groups according to the age when they began smoking. The first, second and third quartiles obtained from the control group frequency distribution for age of starting to smoke were used as the cut-offs for the four groups.

Ever drinkers were defined as those who consumed at least one type of alcoholic beverage (beer, Sato, white whisky, red whisky and other whiskies) at least once a month; those drinking less than this were defined as non-drinkers. The consumption of each participant was calculated in terms of units of alcohol, where a unit corresponds to 10 mL (approximately 8 gm) of ethanol. The number of units of alcohol in a drink was determined by multiplying the volume of the drink (in millilitres) by its alcohol percentage (beer 5.0%, Sato 7.0%, white whisky 40%, red whisky 35%) and dividing by 1000. Drinkers were dichotomised according to the units of alcohol consumed per month on the basis of the median monthly consumption of controls.

Laboratory methods

Specimen collection and DNA extraction

Blood samples (buffy coat) were available for 175 (80%) of the 219 eligible CCA cases; specimens were retrieved from the KKCS bio-bank for these cases and for the 350 matched controls. Genomic DNA was extracted from buffy coat fractions using standard protocols of the Genomic DNA Mini Kit with Proteinase K (Geneaid Biotech). Of those with DNA samples, genotyping was successfully carried out for 95% (499 out of 525) of all samples for XRCC1 and for 90% (474 out of 525) of all samples for OGG1. Laboratory personnel were blinded to the case–control status of the available samples.

PCR amplification and genetic polymorphisms detection

Real-time PCRs with the high-resolution melting analysis (Real-time PCR-HRM) technique of DNA amplification for the DNA BER genes (XRCC1 and OGG1) polymorphisms were performed in a 96-well plate in the LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System.

The amplification of XRCC1 G399A used two primers, [F]:5′-AGT GGG TGC TGG ACT GTC-3′ and [R]:5′-TTG CCC AGC ACA GGA TAA-3′, and was performed in a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System with a final volume of 20 µL containing 10 µL of the master mix, 4.4 µL of H2O, 3 mM of MgCl2, 0.3 µM of each primer and 200 ng of the DNA template. The amplification of the OGG1 C326G was performed in the same way, but the primers were [F]:5′-CCT ACA GGT GCT GTT CAG T-3′ and [R]:5′-CCT TTG GAA CCC TTT CTG-3′.

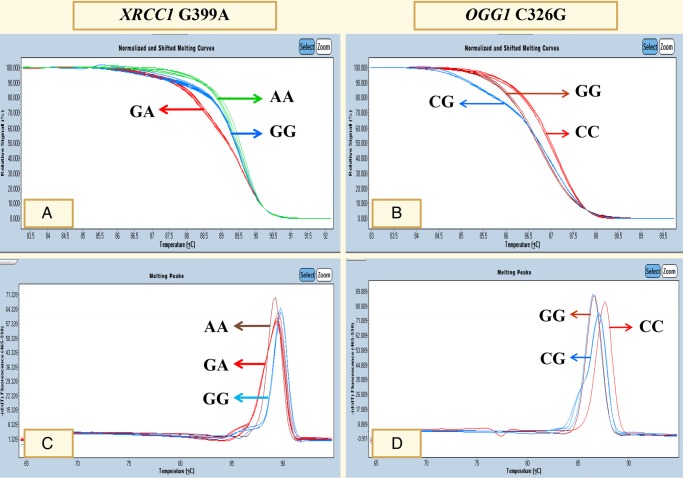

HRM data were analysed using the LightCycler 480 Gene Scanning Software V.1.5 (Roche). Normalised and temperature-shifted melting curves carrying a sequence variation were evaluated and compared with the wild-type sample. Sequence variations were distinguished by the different shapes of melting curves (figure 1A for XRCC1 G399A and figure 1B for OGG1 C326G). Melting peaks of sequence variation were analysed and compared with the wild-type sample. Different plots were distinguished by different melting peaks for each genotype (figure 1C for XRCC1 G399A and figure 1D for OGG1 C326G). To improve the genotyping quality and validation, genotyping of 10% of random samples was confirmed by the PCR with restriction fragment length polymorphism techniques.

Figure 1.

Polymorphisms in XRCC1 G399A and OGG1 C326G were analysed using PCR with high-resolution melting analysis.

Statistical analysis

To assess the strength of the associations between polymorphisms in the DNA BER genes (XRCC1 and OGG1) and the risk of CCA, ORs with 95% CIs were estimated using conditional logistic regression. A univariate analysis using McNemar's χ2 test and conditional logistic regression was carried out to explore the associations between DNA-repair gene polymorphisms, smoking and alcohol drinking, and the risk of CCA. Factors found to have a strong association with CCA in the univariate analysis (p<0.05), and factors without association in the univariate analysis but found to play important roles as factors for CCA risk from literature reviews, were included in the multivariate analysis. Possible modifications of the effects of smoking and alcohol drinking by polymorphisms in XRCC1 G399A and OGG1 C326G were also analysed. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with a statistical package, STATA V.10 (Stata, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

There were 219 cohort members who had developed a primary CCA at 6 months or more after enrolment into the KKCS. They comprised 92 women and 127 men, with a median age of 57 years (minimum 31 and maximum 69). There were two controls matched by age and sex for each case. Table 1 shows the distribution of the XRCC1 G399A and OGG1 C326G polymorphisms in cases and controls, the joint distribution of those polymorphisms, and the associated ORs. While there were no associations between any of these individual polymorphisms and the risk of CCA, the combinations of XRCC1 GA heterozygous and OGG1 CC wild-type or CG heterozygous, and of XRCC1 GG wild-type and OGG1 CG heterozygous, were significantly related to a reduced risk of CCA (p value <0.001). Conversely, the combinations of the OGG1 GG mutant, homozygous with all three genotypes of XRCC1 (wild-type, heterozygous and mutant homozygous), were significantly associated with an increased risk of CCA (p=0.01, 0.03 and 0.004, respectively), but there were no interactions between the polymorphisms of XRCC1 G399A and OGG1 C326G on CCA risk.

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of XRCC1 and OGG1 polymorphisms with the risk of cholangiocarcinoma in Khon Kaen, Thailand

| Cases |

Controls |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic polymorphisms | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | OR* | 95% CI | p Value | |

| XRCC1 G399A† | ||||||||

| GG | 62 | 38.8 | 149 | 44.0 | 1.0 | |||

| GA | 94 | 58.8 | 169 | 49.9 | 1.3 | 0.89 to 1.97 | 0.17 | |

| AA | 4 | 2.5 | 21 | 6.2 | 0.5 | 0.16 to 1.42 | 0.18 | |

| GA or AA (any A allele) | 98 | 61.3 | 190 | 56.1 | 1.2 | 0.82 to 1.78 | 0.33 | |

| OGG1 C326G‡ | ||||||||

| CC | 34 | 23.5 | 95 | 28.9 | 1.0 | |||

| CG | 109 | 75.2 | 229 | 69.6 | 1.4 | 0.86 to 2.23 | 0.18 | |

| GG | 2 | 1.4 | 5 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.22 to 7.03 | 0.80 | |

| CG or GG (any G allele) | 111 | 76.6 | 234 | 71.1 | 1.4 | 0.86 to 2.22 | 0.18 | |

| Joint effects | ||||||||

| XRCC1 G399A | OGG1 C326G | |||||||

| GG | CC | 14 | 9.7 | 41 | 12.7 | 1.0 | ||

| GA | CC | 19 | 13.1 | 47 | 14.5 | 0.3 | 0.15 to 0.55 | <0.001 |

| AA | CC | 2 | 1.4 | 4 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 1.10 to 14.60 | 0.03 |

| GG | CG | 42 | 29.0 | 100 | 30.9 | 0.1 | 0.07 to 0.25 | <0.001 |

| GA | CG | 56 | 38.6 | 108 | 33.3 | 0.1 | 0.07 to 0.22 | <0.001 |

| AA | CG | 3 | 2.1 | 15 | 4.6 | 0.9 | 0.42 to 2.07 | 1.00 |

| GG | GG | 5 | 3.4 | 3 | 0.9 | 4.7 | 1.30 to 25.33 | 0.01 |

| GA | GG | 2 | 1.4 | 4 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 1.10 to 14.60 | 0.03 |

| AA | GG | 2 | 1.4 | 2 | 0.6 | 7.0 | 1.61 to 63.46 | 0.004 |

| p Value for interaction=0.21 | ||||||||

*Crude OR from matched case–control analysis.

†DNA samples for XRCC1 genotyping were successfully carried out for 160 out of 175 cases, and 339 out of 350 controls.

‡DNA samples for OGG1 genotyping were successfully carried out for 145 out of 175 cases, and 329 out of 350 controls.

In the univariate analysis (table 2), there were significant associations between cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption and the risk of CCA, and their joint effect appeared to be multiplicative with no interactions between them. There was trend in risk with smoking frequency or number of years of habitual smoking (p for trend=0.002).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking on the risk of cholangiocarcinoma in Khon Kaen, Thailand

| Cases |

Controls |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | OR* | 95% CI | p Value |

| Cigarette smoking | |||||||

| Non-smoker | 92 | 42.0 | 230 | 52.5 | 1.0 | ||

| Smoker | 127 | 58.0 | 208 | 47.5 | 2.7 | 1.57 to 4.50 | <0.001 |

| Age at which smoking started of all cigarettes (years) | |||||||

| Non-smoker | 92 | 42.0 | 230 | 52.5 | 1.0 | ||

| <17 | 28 | 12.8 | 48 | 11.0 | 2.9 | 1.38 to 5.91 | 0.01 |

| 17–19 | 35 | 16.0 | 44 | 10.1 | 3.6 | 1.85 to 7.17 | <0.001 |

| 20–21 | 40 | 18.3 | 70 | 16.0 | 2.5 | 1.33 to 4.62 | 0.004 |

| 22+ | 24 | 11.0 | 46 | 10.5 | 2.4 | 1.19 to 4.73 | 0.01 |

| p for trend=0.002 | |||||||

| Alcohol consumption | |||||||

| No | 57 | 26.0 | 254 | 58.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Yes | 162 | 74.0 | 184 | 42.0 | 5.7 | 3.61 to 9.04 | <0.001 |

| Units of alcohol per month of all alcohol consumption | |||||||

| Non-drinker | 57 | 26.0 | 254 | 58.0 | 1.0 | ||

| <14 | 79 | 36.1 | 92 | 21.0 | 5.2 | 3.15 to 8.43 | <0.001 |

| ≥14 | 83 | 37.9 | 92 | 21.0 | 6.7 | 3.90 to 11.38 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption and smoking | |||||||

| No alcohol, non-smoker | 42 | 19.2 | 178 | 40.6 | 1.0 | ||

| No alcohol, smoker | 15 | 6.9 | 76 | 17.4 | 2.2 | 0.93 to 5.00 | 0.07 |

| Alcohol drinker, non-smoker | 50 | 22.8 | 52 | 11.9 | 5.8 | 3.12 to 10.78 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol drinker, smoker | 112 | 51.1 | 132 | 30.1 | 10.4 | 5.07 to 21.16 | <0.001 |

| p for trend <0.001 | |||||||

| p Value for interaction=0.68 | |||||||

*Crude OR from matched case–control analysis.

In the multivariate analysis, table 3 shows the adjusted ORs and 95% CIs from the multivariate analysis. There was a clear association with alcohol drinking: compared with non-drinkers, individuals who consumed <14 units of alcohol per month had an increased risk of CCA (OR=5.2, 95% CI 2.74 to 9.95), and the risk was higher still in those who consumed ≥14 units of alcohol per month (OR=7.6, 95% CI 3.67 to 15.72).

Table 3.

Cases and controls, and OR for cholangiocarcinoma associated with smoking, alcohol drinking, and XRCC1 and OGG1 polymorphisms

| Cases |

Controls |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | OR* | OR† | 95% CI‡ | p Value |

| XRCC1 G399A polymorphisms§ | ||||||||

| GG | 62 | 38.8 | 149 | 44.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| GA | 94 | 58.8 | 169 | 49.9 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.76 to 1.94 | 0.43 |

| AA | 4 | 2.5 | 21 | 6.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.10 to 1.62 | 0.20 |

| OGG1 C326G polymorphisms¶ | ||||||||

| CC | 34 | 23.4 | 95 | 28.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| CG | 109 | 75.2 | 229 | 69.6 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.70 to 2.07 | 0.49 |

| GG | 2 | 1.4 | 5 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.10 to 5.11 | 0.75 |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||||

| Non-smoker | 92 | 42.0 | 230 | 52.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Smoker | 127 | 58.0 | 208 | 47.5 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 0.94 to 4.01 | 0.07 |

| Units of alcohol per month of all alcohol consumption | ||||||||

| Non-drinker | 57 | 26.0 | 254 | 58.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| <14 | 79 | 36.1 | 92 | 21.0 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 2.74 to 9.95 | <0.001 |

| ≥14 | 83 | 37.9 | 92 | 21.0 | 6.7 | 7.6 | 3.67 to 15.72 | <0.001 |

*Crude OR from matched case–control analysis.

†Adjusted OR from matched case–control analysis (adjusted for all other variables in the table).

‡95% CI for OR.

§DNA samples for XRCC1 genotyping were successfully carried out for 160 out of 175 cases, and for 339 out of 350 controls.

¶DNA samples for OGG1 genotyping were successfully carried out for 145 out of 175 cases, and for 329 out of 350 controls.

Table 4 shows the results of gene–environment interaction of the XRCC1 and OGG1 polymorphisms along with smoking and alcohol drinking on the risk of CCA. When compared with reference participants (non-smokers with the XRCC1 GG wild-type), smokers carrying the XRCC1 GG wild-type had an increased susceptibility to CCA (OR=2.8, 95% CI 1.30 to 5.91), and this was higher still in smokers with GA heterozygous (OR=3.4, 95% CI 1.60 to 7.28). Moreover, smokers with the OGG1 CC wild-type and CG heterozygous had an increased risk of CCA compared with non-smokers with the wild-type. With respect to alcohol consumption, some combinations of alcohol drinking and mutant polymorphisms of XRCC1 and OGG1 were statistically significant. For example, compared with the reference group (non-drinkers with the XRCC1 GG wild-type), participants with the XRCC1 GA heterozygous who were non-drinkers or drinkers (<14 units of alcohol per month) had an increased susceptibility to CCA (4.4-fold increased to 8.8-fold). Similarly, participants with the XRCC1 AA variant genotype had an increased risk of CCA (9.2-fold in non-drinkers increased to 10.3-fold in drinkers of <14 units of alcohol per month). Again, there were no interactions between the XRCC1 or OGG1 polymorphisms and smoking or alcohol drinking.

Table 4.

Gene–environment interactions of XRCC1 and OGG1 polymorphisms together with smoking and alcohol drinking on cholangiocarcinoma risk in Khon Kaen, Thailand

| Smoking | Cases | Controls | Smoking | Cases | Controls | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XRCC1 | Use of alcohol | n | n | OR* | 95% CI | p Value | OGG1 | Use of alcohol | n | n | OR* | 95% CI | p Value |

| G399A | All cigarettes smoking | 0.87† | C326G | All cigarettes smoking | 0.54† | ||||||||

| GG | Non-smoker | 22 | 71 | 1.0 | CC | Non-smoker | 14 | 55 | 1.0 | ||||

| GA | Non-smoker | 48 | 99 | 1.5 | 0.82 to 2.79 | 0.18 | CG | Non-smoker | 49 | 122 | 1.5 | 0.77 to 2.99 | 0.22 |

| AA | Non-smoker | 2 | 11 | 0.6 | 0.11 to 2.74 | 0.47 | GG | Non-smoker | 1 | 1 | – | – | – |

| GG | Smoker | 40 | 78 | 2.8 | 1.30 to 5.91 | 0.01 | CC | Smoker | 20 | 40 | 3.1 | 1.17 to 8.38 | 0.02 |

| GA | Smoker | 46 | 70 | 3.4 | 1.60 to 7.28 | 0.001 | CG | Smoker | 60 | 107 | 4.3 | 1.79 to 10.21 | 0.001 |

| AA | Smoker | 2 | 10 | 1.2 | 0.21 to 6.29 | 0.86 | GG | Smoker | 1 | 4 | 1.5 | 0.14 to 15.44 | 0.74 |

| G399A | Units of alcohol per month of all alcohol drinking | 0.80† | C326G | Units of alcohol per month of all alcohol drinking | 0.74† | ||||||||

| GG | Non-drinker | 16 | 83 | 1.0 | CC | Non-drinker | 10 | 65 | 1.0 | ||||

| GA | Non-drinker | 20 | 33 | 4.4 | 1.81 to 10.83 | 0.001 | CG | Non-drinker | 9 | 9 | 8.1 | 2.30 to 28.36 | 0.001 |

| AA | Non-drinker | 26 | 33 | 9.2 | 3.65 to 23.21 | <0.001 | GG | Non-drinker | 15 | 21 | 8.6 | 2.62 to 28.02 | <0.001 |

| GG | <14 | 22 | 102 | 1.1 | 0.49 to 2.28 | 0.89 | CC | <14 | 24 | 130 | 1.3 | 0.55 to 3.20 | 0.52 |

| GA | <14 | 39 | 35 | 8.8 | 3.76 to 20.71 | <0.001 | CG | <14 | 46 | 58 | 7.0 | 2.85 to 17.39 | <0.001 |

| AA | <14 | 33 | 32 | 10.3 | 4.14 to 25.80 | <0.001 | GG | <14 | 39 | 41 | 11.2 | 4.18 to 30.17 | <0.001 |

| GG | ≥14 | 1 | 12 | 0.4 | 0.05 to 3.71 | 0.44 | CC | ≥14 | 0 | 1 | – | – | – |

| GA | ≥14 | 2 | 3 | 2.8 | 0.31 to 25.41 | 0.36 | CG | ≥14 | 1 | 1 | 7.7 | 0.29 to 26.73 | 0.22 |

| AA | ≥14 | 1 | 6 | 2.5 | 0.25 to 23.99 | 0.44 | GG | ≥14 | 1 | 3 | 6.4 | 0.48 to 86.72 | 0.16 |

*Crude OR from matched case–control analysis.

†p Value for interaction.

Discussion

This was a case–control study nested within the 23 584 KKCS.11 12 22 The design of this study minimises the recall bias of cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking, as participants were interviewed at the time of recruitment, before case or control status was defined. This design is very useful for examining the role of self-reported factors such as cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption, which are modified when cancer is present.

Smoking was not associated with CCA development in this study (after adjustment for all other variables in the multivariate analysis)—polymorphisms in XRCC1 and OGG1, cigarette smoking and units of alcohol per month of all alcohol consumption.

Alcohol consumption was significantly associated with an increased risk of CCA in previous studies in Thailand18 19 and elsewhere.21 Alcohol may affect the metabolic pathways of endogenous and exogenous nitrosamines,16 19 and it is associated with the production of free radical intermediates, which can cause several kinds of DNA lesions.4 15 16 Reduced repair of these DNA lesions would therefore constitute a major risk factor for cancer development.15 16

The genotype frequencies of the XRCC1 and OGG1 polymorphisms found in controls for this study were consistent with those found in other studies in Thailand: the prevalence of the G allele of XRCC1 codon 399 was 68.88% in this study compared with 36.59–73.20% in other studies,10 23–25 and the A allele of XRCC1 codon 399 was 31.12% in controls (prevalence of A allele was 26.80–52.56%). In our analysis of OGG1 codon 326, the genotype distribution in controls deviated from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The genotype frequency of OGG1 C326G in controls was slightly higher than the rates noted in reports from other studies in Thailand.10 24 26 The C allele of OGG1 codon 326 was 63.68% in controls (the C allele prevalence was between 50.12% and 55.00%) and the G allele of OGG1 codon 326 was 36.32% in controls (the prevalence of the G allele in OGG1 codon 326 was between 45.00% and 49.88%).

XRCC1 and OGG1 are major DNA repair genes involved in BER. Mutations and polymorphisms in DNA repair genes, which affect the efficiency of DNA damage repair, may increase an individual's susceptibility to several cancers,23–26 including cancers of the hepatobiliary tract.5–7 However, no studies on this topic have been conducted in relation to CCA susceptibility, and especially not in Thailand where the incidence of CCA is the highest in the world.17 However, there are four studies in a Thai population which investigated relationships between the BER gene polymorphisms and other common cancers. Whereas XRCC1 G399A polymorphisms tend to be associated with a reduced risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma,23 they are associated with increased risks of breast24 and cervical cancers,25 and OGG1 C326G polymorphisms tend be related to increased risks of breast24 and lung cancers.26

Several studies have explored the associations between polymorphisms of the DNA repair genes involved in BER (XRCC1 G399A and OGG1 C326G) and the risk of various cancers, but they have shown inconsistent results. This may be the consequence of the different modifying effects which these polymorphisms have on the balance during the DNA repair process.

An imbalance in the tightly regulated process can be caused by SNPs and will result in deficient DNA repair and an increase in DNA breaks.27 The XRCC1 codon 399 A allele and the OGG1 326 G allele have been associated with a reduced capacity of the DNA repair process as detected by the persistence of DNA bulky adducts28–30 and γ-irradiation induced oxidative DNA damage.31 In addition, the balance may be modified by smoking-induced and alcohol-induced oxidative DNA base modifications interacting with the repair inefficiency of BER polymorphisms4; for example, the XRCC1 GA variant heterozygous carriers, who were non-drinkers or drinkers of <14 units of alcohol per month, had an increased susceptibility to CCA (4.4-fold in non-drinkers increased to 8.8-fold in drinkers) when compared with non-drinkers carrying the XRCC1 GG wild-type (table 4).

In conclusion, this study is the first report of possible associations between the main polymorphisms in BER genes (XRCC1 G399A, OGG1 C326G), the joint effects of both genes, and their modification of the effects of cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking on CCA risk in a Thai population. Our results suggest that polymorphisms in the XRCC1 and OGG1 genes, particularly in combination, were associated with increased susceptibility to CCA. CCA is a multifaceted disease requiring a broad range of preventative actions. In the context of this study, there is a need for more effective programmes for smoking cessation and reducing alcohol consumption, targeted especially at subgroups which are genetically at particular risk for CCA. Such an approach could also help in the prevention of other forms of cancer.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NS, SP, CP, TE and SW conceived and designed the research. NS and PC performed the research. NS and SP carried out the analyses. All authors contributed to the writing and revisions of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This research was supported by the Thailand Research Fund (Research grant No. 540102) and the National Research University Project of Thailand, Office of the Higher Education Commission, through the Center of Excellence in Specific Health Problems in Greater Mekong Sub-region (SHeP-GMS), Khon Kaen University (Research grant No. NRU542005).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research (Reference No. HE512053).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. GLOBOCAN 2008 v2.0, Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No.10 (Internet). Lyon, France: IARC, 2010. http://globocan.iarc.fr (accessed 27 Mar 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khuhaprema T, Attasara P, Sriplung H, et al. Cancer in Thailand volume VI, 2004–2006. Bangkok: NCIB, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkin DM, Ohshima H, Srivatanakul P, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: epidemiology, mechanisms of carcinogenesis and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1993;2:537–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stern MC, Conti DV, Siegmund KD, et al. DNA repair single-nucleotide polymorphisms in colorectal cancer and their role as modifiers of the effect of cigarette smoking and alcohol in the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16:2363–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang WY, Gao YT, Rashid A, et al. Selected base excision repair gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to biliary tract cancer and biliary stones: a population-based case-control study in China. Carcinogenesis 2008;29:100–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang M, Huang WY, Andreotti G, et al. Variants of DNA repair genes and the risk of biliary tract cancers and stones: a population-based study in China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:2123–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srivastava A, Srivastava K, Pandey SN, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms of DNA repair genes OGG1 and XRCC1: association with gallbladder cancer in North Indian population. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:1695–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thanan R, Murata M, Pinlaor S, et al. Urinary 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine in patients with parasite infection and effect of antiparasitic drug in relation to cholangiocarcinogenesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:518–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dechakhamphu S, Pinlaor S, Sitthithaworn P, et al. Lipid peroxidation and etheno DNA adducts in white blood cells of liver fluke-infected patients: protection by plasma alpha-tocopherol and praziquantel. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:310–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng L, You G, Tanaka H, et al. Combined effects of polymorphisms of DNA-repair protein genes and metabolic enzyme genes on the risk of cholangiocarcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2013;43:1190–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Songserm N, Promthet S, Sithithaworn P, et al. MTHFR polymorphisms and Opisthorchis viverrini infection: a relationship with increased susceptibility to cholangiocarcinoma in Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011;12:1341–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Songserm N, Promthet S, Sithithaworn P, et al. Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma in high-risk area of Thailand: role of lifestyle, diet and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms. Cancer Epidemiol 2012;36:e89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kosti O, Byrne C, Meeker KL, et al. Mutagen sensitivity, tobacco smoking and breast cancer risk: a case-control study. Carcinogenesis 2010;31:654–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rouissi K, Ouerhani S, Hamrita B, et al. Smoking and polymorphisms in xenobiotic metabolism and DNA repair genes are additive risk factors affecting bladder cancer in Northern Tunisia. Pathol Oncol Res 2011;17:879–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mena S, Ortega A, Estrela JM. Oxidative stress in environmental-induced carcinogenesis. Mutat Res 2009;674:36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pelucchi C, Tramacere I, Boffetta P, et al. Alcohol consumption and cancer risk. Nutr Cancer 2011;63:983–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parkin DM, Srivatanakul P, Khlat M, et al. Liver cancer in Thailand. I. A case-control study of cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Cancer 1991;48:323–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chernrungroj G. Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma: a case-control study [dissertation]. Connecticut: Yale University, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honjo S, Srivatanakul P, Sriplung H, et al. Genetic and environmental determinants of risk for cholangiocarcinoma via Opisthorchis viverrini in a densely infested area in Nakhon Phanom, northeast Thailand. Int J Cancer 2005;117:854–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poomphakwaen K, Promthet S, Kamsa-Ard S, et al. Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma in Khon Kaen, Thailand: a nested case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2009;10:251–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chalasani N, Baluyut A, Ismail A, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a multicenter case-control study. Hepatology 2000;31:7–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sriamporn S, Parkin DM, Pisani P, et al. A prospective study of diet, lifestyle, and genetic factors and the risk of cancer in Khon Kaen Province, northeast Thailand: description of the cohort. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2005;6:295–303 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kietthubthew S, Sriplung H, Au WW, et al. Polymorphism in DNA repair genes and oral squamous cell carcinoma in Thailand. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2006;209:21–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sangrajrang S, Schmezer P, Burkholder I, et al. Polymorphisms in three base excision repair genes and breast cancer risk in Thai women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;111:279–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Settheetham-Ishida W, Yuenyao P, Natphopsuk S, et al. Genetic risk of DNA repair gene polymorphisms (XRCC1 and XRCC3) for high risk human papillomavirus negative cervical cancer in Northeast Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011;12:963–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klinchid J, Chewaskulyoung B, Saeteng S, et al. Effect of combined genetic polymorphisms on lung cancer risk in northern Thai women. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2009;195:143–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohrenweiser HW, Wilson DM III, Jones IM. Challenges and complexities in estimating both the functional impact and the disease risk associated with the extensive genetic variation in human DNA repair genes. Mutat Res 2003;526:93–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lunn RM, Langlois RG, Hsieh LL, et al. XRCC1 polymorphisms: effects on aflatoxin B1-DNA adducts and glycophorin A variant frequency. Cancer Res 1999;59:2557–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duell EJ, Millikan RC, Pittman GS, et al. Polymorphisms in the DNA repair gene XRCC1 and breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001;10:217–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matullo G, Guarrera S, Carturan S, et al. DNA repair gene polymorphisms, bulky DNA adducts in white blood cells and bladder cancer in a case-control study. Int J Cancer 2001;92: 562–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vodicka P, Stetina R, Polakova V, et al. Association of DNA repair polymorphisms with DNA repair functional outcomes in healthy human subjects. Carcinogenesis 2007;28:657–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.