Abstract

Schedule control and supervisor support for family and personal life are work resources that may help employees manage the work-family interface. However, existing data and designs have made it difficult to conclusively identify the effects of these work resources. This analysis utilizes a group-randomized trial in which some units in an information technology workplace were randomly assigned to participate in an initiative, called STAR, that targeted work practices, interactions, and expectations by (a) training supervisors on the value of demonstrating support for employees’ personal lives and (b) prompting employees to reconsider when and where they work. We find statistically significant, though modest, improvements in employees’ work-family conflict and family time adequacy and larger changes in schedule control and supervisor support for family and personal life. We find no evidence that this intervention increased work hours or perceived job demands, as might have happened with increased permeability of work across time and space. Subgroup analyses suggest the intervention brings greater benefits to employees more vulnerable to work-family conflict. This study advances our understanding of the impact of social structures on individual lives by investigating deliberate organizational changes and their effects on work resources and the work-family interface with a rigorous design.

Keywords: work-family conflict, organizations, experiment, group-randomized trial, schedule control

Work-family conflict is increasingly common among U.S. workers (Jacobs and Gerson 2004, Nomaguchi 2009, Winslow 2005), with about 70 percent of workers reporting some interference between work and non-work (Schieman, Milkie, and Glavin 2009). Work-family conflict has grown because of increases in women’s labor force participation (meaning more households have all adults employed) and rising expectations for fathers’ involvement in daily care of children (Nomaguchi 2009). Work-family conflict also arises because work organizations have not changed much in response. The institutionalized expectation in U.S. workplaces is that serious, committed, promotable employees will work full-time (and longer), full-year, on a schedule determined by the employer, with no significant breaks in employment (Blair-Loy 2003, Moen and Roehling 2005, Williams 2000). Trying to live up to this ideal creates work-family conflict for employees who have significant caregiving responsibilities, but also for the growing proportion of single workers and dual-earning couples who do not have a partner at home to take of all the “little things” that need to be done (Schieman, Milkie, and Glavin 2009). The goal of this study is to assess the effects of an innovative workplace intervention on work-family conflict and related work conditions.

Scholars and advocates concerned about work-family conflict have argued for changing the social structure of workplaces, i.e. the largely taken-for-granted and mutually reinforcing practices, interactions, expectations, policies, and reward systems that reflect and reinforce the ideal worker schema (Acker 1990, Albiston 2010, Williams 2000). These calls recognize the constraining power of social structures, understood as “mutually sustaining cultural schemas and sets of resources” (Sewell 1992: 27), but also acknowledge that agents can, in theory, reconfigure those structures through changing their everyday practices, interactions, and the social meanings attached to them. These theoretical precepts inform our understanding of the sources of work-family conflict but also point to the possibility for meaningful change through interventions that address these multiple, interlocking levels.

This project is also informed by middle-range theory regarding the work conditions most relevant to work-family conflict. Guided by the job demands-resources model (Bakker and Demerouti 2007), scholars have viewed flexibility (or schedule control) and support as key work resources that can reduce work-family conflict (Schieman et al. 2009, Voydanoff 2004). Work resources are the “physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job” that help workers accomplish their work tasks and/or reduce the “physiological or psychological costs” of work demands (Bakker and Demerouti 2007:312). Schedule control and support are work resources that ameliorate work-family conflict because they make it easier to get the work done and offset the stress of feeling pulled in two directions.1

While many studies tie schedule control and supervisor support to work-family conflict and related outcomes (as we review below), the causal claims that can be made are limited. This study supports stronger causal claims by conducting a group-randomized trial in which some work units received an intervention (i.e., a new workplace initiative that represents the experimental treatment) while other units continued with “business as usual.” We evaluate the effects of this intervention on employees’ schedule control, supervisors’ support for family and personal matters as reported by employees, and the work-family interface. We utilize two waves of data from employees in the information technology (IT) division of a U.S. Fortune 500 organization; our pseudonym for the company is TOMO. The intervention is called STAR, short for “Support. Transform. Achieve. Results.” STAR aims to modify the practices, interactions, and social meanings within this workplace, specifically targeting employees’ control over when and where they work and supervisors’ support for family and personal life in hopes of reducing work-family conflict and promoting employee wellbeing.

CHANGING WORK TO REDUCE WORK-FAMILY CONFLICT

Previous Research and Its Limitations

Before reviewing empirical studies on the relationships between schedule control, supervisor support for family and personal life, and work-family conflict, we clarify our understanding of those terms. Because “flexibility” is sometimes used to refer to a management strategy of easily eliminating workers or relying on contingent staff, we prefer the more specific term of schedule control to refer to employees’ control over the timing of their work, the number of hours they work, and the location of their work (Berg et al. 2004, Kelly, Moen, and Tranby 2011, Lyness et al. 2012, Schieman et al. 2009). Supervisor support for family and personal life involves providing emotional support for employees’ work-life challenges, modeling how supervisors themselves handle work-family issues, looking for creative solutions that meet the needs of both employees and the organizations, and facilitating employees’ flexible work practices (Hammer et al. 2009). This form of support is more closely associated with work-family conflict than is general supervisor support when comparing effects in the same sample (Hammer et al. 2009) and with meta-analysis (Kossek et al. 2011). We use the broad terms of work-family interface and work-family conflict interchangeably, to refer to challenges managing paid work and nonwork and the sense that family time is squeezed or inadequate. We use the directional terms (work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict) more specifically to describe the degree to which role responsibilities from one domain are perceived as interfering with the other domain (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985, Netemeyer et al. 1996). Changes in the work environment may be more salient for work-to-family conflict but family-to-work conflict may decrease as expectations shift within the workplace (e.g. coming in to work later due to a school appointment is no longer experienced as a problem). Note that the measures of conflict refer to personal life and family, so they are also salient to those with few family responsibilities.

Many studies have considered the relationship between these work resources and the work-family interface. Employees who report more control over their schedules have lower work-family conflict (Byron 2005, Galinsky, Bond, and Friedman 1996, Galinsky, Sakai, and Wigton 2011, Hammer, Allen, and Grigsby 1997, Kossek, Lautsch, and Eaton 2006, Moen, Kelly, and Huang 2008, Roeters, Van der Lippe, and Kluwer 2010) and better work-life balance (Hill et al. 2001, Tausig and Fenwick 2001). Employees who report more support from supervisors – particularly with regard to work-family issues – also report lower work-family conflict (Allen 2001, Batt and Valcour 2003, Frone, Yardley, and Markel 1997, Frye and Breaugh 2004, Hammer et al. 2009, Kossek et al. 2011, Lapierre and Allen 2006, Thomas and Ganster 1995, Thompson, Beauvais, and Lyness 1999) and believe their organizations to be more helpful with work-family balance (Berg, Kalleberg, and Appelbaum 2003).

We identify two concerns regarding this body of research. First, the vast majority of these studies are cross-sectional and non-experimental, and so do not fully support causal claims. These design limitations are serious because employees have differential access to schedule control, supervisor support, and organizational work-family policies, with clear variation by education and occupational status (Davis and Kalleberg 2006, Golden 2008, Lyness et al. 2012, Schieman et al. 2009, Swanberg et al. 2011). The apparent inverse relationship between each resource and work-family conflict may reflect, at least in part, the selection of individuals with higher human and social capital into “good jobs” with “good employers” (Weeden 2005, Wharton, Chivers, and Blair-Loy 2008). Employees who enjoy these work resources often have higher incomes, higher occupational status, and perhaps fewer family demands because they are more likely to have spouses who are not employed, fewer children, socially and financially stable elders, and financial resources to outsource various “little things” that need to get done. However, some research finds that employees in these “good jobs” are often working longer hours, facing higher job demands, and investing more psychologically in their paid work; the “stress of higher status” helps explain the higher work-to-family conflict reported by those employees in some studies (Schieman, Whitestone, and Van Gundy 2006; Schieman et al. 2009). Previous cross-sectional studies examining work-family conflict have generally controlled for work hours (and sometimes controlled for job demands or psychological involvement), but a stronger design would attempt to manipulate those work resources while holding work demands constant, as we do here.

The second concern is that previous studies do not provide clear guidance on how to foster these work resources. The research on common work-life policies finds mixed evidence regarding their impact on schedule control or supervisor support for family and personal life (Kelly et al. 2008, Kossek and Michel 2011). Flextime and telecommuting policies may be formally available in a given organization, but employees’ ability to use those arrangements varies according to their occupational status and their managers’ preferences or whims (Blair-Loy and Wharton 2002, Eaton 2003). Furthermore, in most organizations, these flexible work arrangements are treated as individual accommodations for valued employees (Kelly and Kalev 2006) and often carry career penalties for use (Glass 2004, Leslie et al. 2012, Wharton et al. 2008). When managers determine access to flexible work options, employees may not feel they have much schedule control or experience lower work-family conflict (Batt and Valcour 2003, Tausig and Fenwick 2001). In light of the mixed evidence on flextime and telecommuting policies, scholars and practitioners have argued for broader efforts moving beyond simply putting a new policy “on the books” (Lewis 1997, Mennino, Rubin, and Brayfield 2005, Thompson et al. 1999). This study involves a rigorous evaluation of one such effort.

The issue with regard to fostering supervisor support for family and personal life is that there are few interventions and even fewer that have been studied. Management training is a viable option, but scholars first needed to identify what behaviors constitute and convey supervisor support for family and personal life in order to design appropriate training (Hammer et al. 2007). Scholars have long recognized the critical role of supervisors in interpreting policies and acting as gatekeepers to use of flexible work and family leave policies (Blair-Loy and Wharton 2002, Hochschild 1997, Kossek, Barber, and Winters 1999) but only recently have researchers identified other dimensions of supervisor support for family and personal life such as providing emotional support, sharing how one handles work-family challenges, and looking for creative solutions that meet the needs both employees and the organizations (Hammer et al. 2007, Hammer et al. 2009).

Recent Studies of Workplace Interventions

Building on the cross-sectional research on schedule control and supervisor support for family and the work-family interface, two recent studies provide the strongest evidence to date on the possibility of manipulating schedule control and supervisor support for family and personal life and the effects of those changes on the work-family interface. In a study of the Results Only Work Environment (ROWE) initiative at the corporate headquarters of Best Buy, Co., Inc., Kelly, Moen, and Tranby (2011) showed that employees in departments participating in ROWE in the study period saw significantly increased schedule control and improvements in the work-family interface as compared to the changes reported by employees in departments that continued operating in traditional ways. ROWE employees also improved health behaviors (e.g., sleep before work days, going to the doctor when sick) compared to employees in traditional departments (Moen et al. 2011). These findings point to the possible benefits of broad initiatives targeting schedule control – as opposed to individually negotiated flexible work options – but the study did not involve randomization to “treatment” (instead studying a phased roll-out of ROWE) and the intervention and control groups were not fully equivalent at baseline (Kelly et al. 2011).

Second, Hammer, Kossek, Bodner, Anger, and Zimmerman (2011) evaluated an intervention targeting supervisors’ support for family and personal life in 12 grocery store sites. The training described how supervisors could demonstrate support for employees’ family and personal lives, with a self-monitoring activity to help supervisors practice supportive behaviors. Work-family conflict was investigated as a moderator of the intervention effects, rather than a primary outcome. Hammer and colleagues found that employees with high family-to-work conflict at baseline who worked in stores that received training reported higher levels of job satisfaction and physical health and lower turnover intentions than similar employees in control stores, while employees who began with low levels of family-to-work conflict reported lower job satisfaction and physical health and higher turnover intentions than similar employees in control stores (Hammer et al. 2011:141). The intervention may have created a negative backlash among those who did not feel company resources were used to benefit them, and that supervisors’ attention on those with high family-to-work conflict may have frustrated other employees (Hammer et al. 2011:142). This study demonstrated the value of training supervisors to express support for family and personal life, while suggesting that work-family “interventions may be most effective for those most in need” (Hammer et al. 2011: 147).

Contributions

We advance the work-family literature by investigating an innovative workplace intervention and by utilizing a group-randomized trial (GRT, also called a cluster randomized trial or place-based experiment). As we describe below, we integrated the interventions reviewed above to target both schedule control and supervisor support for family and personal life. The intervention aimed to alter the social environment itself, as experienced through everyday work practices, interactions, and the social meaning of work patterns. Within the work-family field, there are almost no GRTs or other experiments attempting to change the social environment. Two important exceptions were both conducted outside the U.S. First, a recent experiment in a Chinese call center randomized individuals to work at home or in the office; researchers found improved work performance and job satisfaction and reduced turnover for those working at home (Bloom et al. 2013). Interestingly, after the experimental period in which those randomized to work at home were obligated to do so, employees were able to choose where they worked and outcomes improved even more (Bloom et al. 2013), suggesting the value of increased employee control. Second, in a group-randomized trial of self-scheduling among nurses in a Danish hospital, nurses in the treatment teams reported greater improvements in work-life balance, job satisfaction, satisfaction with hours, and social support than the nurses in the control condition (Pryce et al. 2006).2

This study also has implications well beyond work-family scholarship and the study of work organizations and employee wellbeing. Sociologists and other social scientists have turned their attention to randomized experiments in conjunction with a revived commitment to causal inference and counterfactual thinking (Gangl 2010, Morgan and Winship 2007, Winship and Morgan 1999). Yet, sociologists have rarely conducted group-randomized trials – the very experiments that would help identify the effects of social structures or social environments more conclusively (Cook 2005, Oakes 2004). While some recent educational research uses GRTs to examine innovations in schools (e.g., Borman et al. 2007, Cook et al. 2000, Raudenbush, Martinez, and Spybrook 2007) and occupational health studies increasingly involve GRTs (Landsbergis et al. 2011, van der Klink et al. 2001), sociologists of work and organizations have not yet pursued group-randomized trials to investigate the effects of specific workplace policies or initiatives on employees and the organization itself.

In some cases, GRTs involve group randomization simply to achieve “economies of spatial concentration” (Bloom 2006:120–1). In those studies, the intervention target is individual behavior change and randomization occurs at the group level primarily for convenience and ease of intervention delivery. For example, when workplace-based smoking cessation interventions randomize at the workplace level, they do so for ease of delivering smoking cessation messages to individuals within those site and in order to avoid contamination of intervention activities into control groups (e.g., Okechukwu et al. 2009, Sorensen et al. 2002). Other GRTs aim to “induce organizational change” such as “whole-school reforms” and employer-based initiatives that invite change in or practices (Bloom 2006). We employ a GRT design because randomizing individuals is not appropriate for a social intervention, such as STAR, that targets individual and team practices, interactions, expectations, and norms.

INTERVENTION OVERVIEW

STAR included (a) supervisory training on strategies to demonstrate support for employees’ personal and family lives while also supporting employees’ job performance and (b) participatory training sessions that identify new work practices and processes to increase employees’ control over work time and focus on key results, rather than face time. STAR as implemented in TOMO included eight hours of participatory sessions for employees (with managers present) and an additional four hours for managers. Managers were first oriented to the STAR initiative in a facilitated training session and then completed a self-paced, computer-based training lasting about an hour. The computer-based training reviewed demographic changes, described the impact of work-family conflict on business outcomes (such as turnover and employee engagement), and claimed that demonstrating support for subordinates’ personal and family life could benefit both employees and the organization. The training reviewed ways that managers could demonstrate “personal support” and “performance support” and invited managers to set goals for exhibiting supportive behaviors over the coming week. They carried an iPod Touch™ with an alarm reminder to log those behaviors. Managers received personalized feedback charts describing which types of supportive behaviors they had concentrated on and whether they had met their goals, as well seeing the mean scores for other managers in STAR. This self-monitoring task was intended to help them reflect on their own behaviors; feedback was delivered individually, and information was not shared with executives. A second self-monitoring task was completed about one month after the first. Managers also participated in a facilitated training session specific to supervisors towards the end of the STAR roll-out; this provided managers an opportunity to share what was working well in their teams and to ask questions of the facilitators and peers.

Participatory training sessions attended by employees and managers prompted discussions of the organization’s expectations of workers, everyday practices, and company policies, and encouraged new ways of working that increase employees’ control over their work time and demonstrate greater support for others’ personal obligations. Sessions were both highly scripted and very interactive. Structured messages were presented to all, but participants responded differently to activities and questions. Facilitators argued that expectations that everyone works from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the office do not reflect current technologies, employees’ preferences given their personal obligations, or some team’s need to interface with offshore staff. Facilitators critiqued the assumption that employees seeking more flexibility were less committed or productive, instead claiming that employees would be more engaged in their work, more responsive to customers’ and co-workers’ needs, and happier if they had more control over their schedules. Then, using a variety of role plays and games, participants discussed how, when, and where they would like to work, how they could coordinate and communicate if hours were more varied and more employees worked remotely, and what everyday practices and interactions would need to change to support new work patterns. Common changes discussed were setting up conference call lines for meetings, clarifying tasks so “face time” is not used to evaluate productivity or commitment, contacting co-workers by instant message rather than stopping by their cubes, and deciding whether a one or two hour break (e.g. a walk or errand during the work day) needed to be announced to one’s team or not. Several work groups reporting to the same executive participated in each session. This allowed employees to hear their manager’s perspective, and vice versa, but also exposed them to other teams’ approaches to these issues.

Although STAR primarily targeted practices and interactions at the team level, the intervention also aligned these practices with an existing policy. Company policy required employees who wanted to work at home routinely to file a telecommuting agreement that had to be approved by their manager, director, and VP. Employees in STAR filled out the company’s regular telecommuting agreement but the whole group was granted blanket approval by their VP, rather than the case-by-case approval used before STAR (and in usual practice groups). The blanket approval was discussed in the first session and signaled top management’s support for changes associated with STAR. Later sessions helped employees and managers jointly decide how much work at home was appropriate for different jobs and how teams would communicate and coordinate with more variable schedules and more remote work.

Compared to most work-family initiatives, STAR is different in its collective and multilevel approach. Rather than select individual employees having access to a flexible schedule or telecommuting based on their manager’s approval of a request (Blair-Loy and Wharton 2002, Briscoe and Kellogg 2011), groups of employees were randomized to STAR. To elaborate: STAR’s attempt to shift schedule control from managers to employees facilitates work at home and variability in work hours (i.e. changes individual work practices) but also changes interactions at work because employees no longer ask permission to adjust their schedules or work location. STAR also alters the social meaning of these work patterns from being a special “accommodation” that may signal lesser commitment to being routine and accepted (Kelly et al. 2010, Kossek et al. 2011). Similarly, the broad effort to encourage managers to demonstrate support for employees’ family and personal lives likely increases conversations about what is happening outside of work (i.e. changes interactions) while also encouraging changes in work practices, such as a manager attending a meeting for an employee who has an important work deadline or family obligation. These new interactions and practices have broader social meaning, signaling leadership’s recognition and legitimation of employees’ lives outside of work.

STAR’s approach is consistent with pioneering action research that uses collective dialogues to reevaluate work processes and practices in the hopes of advancing both the organization’s goals and work-life fit (Bailyn 2011, Perlow 1997, Perlow 2012, Rapoport et al. 2002). However, our experimental design allows for a more rigorous evaluation of the initiative than has been possible in those studies. Moreover, STAR pairs bottom-up changes identified by employees with structured training to promote managerial supportiveness.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

We investigate four broad research questions.

Does STAR increase employees’ schedule control and their reports of supervisor support for family and personal life?

-

Does STAR improve employees’ experience of the work-family interface? Specifically, does STAR reduce work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict and increase perceived time adequacy for family among TOMO employees at six-months follow up?

We hypothesize that STAR will increase schedule control, employees’ perceptions of their supervisors’ support for family and personal life, and family time adequacy, and that STAR will reduce conflict between work and family in both directions. This expectation is based on cross-sectional research that finds a relationship between the intended targets of STAR, schedule control and family-supportive supervision, and work-family conflict as well as the recent studies of similar workplace interventions. Yet there are several reasons STAR might have no or very limited effects. First, STAR critiques past management practices, such as managers setting schedules, rewarding “face time” or visibility, and expecting employees to drop personal concerns while they are at work. Resistance to these changes might arise from both managers and employees who have built careers under the old expectations, as has been seen in other participatory management initiatives (Smith 2001, Vallas 2003). Second, the study of ROWE in Best Buy found positive effects (Kelly et al. 2011, Moen et al. 2011), but a randomized evaluation of a similar initiative might not find changes in another organization. ROWE was “homegrown” within the company and therefore customized to that organizational culture and workforce. STAR, in contrast, was brought into the organization and delivered by outside consultants. Additionally, STAR was implemented in TOMO as a pilot program with the understanding that top executives were not ready to adopt it across-the-board. In this study, work units were randomized to STAR or “usual practice” conditions. Some employees and mid-level managers may have believed that the executives above them were not supportive and were therefore cautious about STAR themselves. Third, STAR’s manager training component has not been previously shown to reduce work-family conflicts; the pilot study in grocery stores evaluated work-family conflict as a moderator of other work and health outcomes (Hammer et al. 2011). Finally, during the course of the study, it was announced that TOMO would be acquired by another firm (with the merger finalized after the follow-up data analyzed here). This reflects the reality of conducting field experiments, in that all conditions could not be controlled. The merger announcement raised questions about whether the current organizational culture would be sustained into the future and may have decreased employees’ investment in STAR. Employees facing organizational restructuring often feel that implementing workplace interventions is unwise (Egan et al. 2007, Olsen et al. 2008).

Does the STAR initiative make conditions worse for employees by increasing their work hours or job demands? Such unintended consequences might arise because of increased permeability of work and nonwork across time and space and the resulting blurring of work and family roles (Chesley 2005, Glavin and Schieman 2010, Kelliher and Anderson 2010, Schieman and Glavin 2008). Employees may gain more control over when and where they work but simultaneously find themselves working more or feeling more pressed at work. Though generally conceptualized as a work resource, schedule control may operate more to intensify work demands by increasing employees’ exposure to job pressures (Schieman 2013). This dynamic may be especially likely in a salaried, professional workforce like TOMO, where the employer does not pay overtime (so the employer has an interest in getting as many hours of work as possible) and where employees’ devotion to work is both expected and experienced as intrinsically rewarding (Blair-Loy 2003, 2009, Perlow 2012).

Do the effects of STAR differ depending on employees’ vulnerability to work-family conflicts? In other words, are there heterogeneous treatment or intervention effects? Previous research finds that employees with higher family demands, captured by having children living at home and providing care for elderly relatives or other dependent adults, have greater work-family strain and thus a greater need for a flexible, supportive work environment (Michel et al. 2011, Moen et al. 2012). Family responsibilities are gendered, with mothers and wives still doing significantly more housework and child care, on average (Bianchi et al. 2012). Also, work-family strains seem to weigh more heavily on mothers’ wellbeing than fathers (Nomaguchi, Milkie, and Bianchi 2005) and there is some evidence that mothers feel the burden of normative judgments even when they are viewed as high performers at work (Benard and Correll 2010). This suggests that mothers and fathers may benefit differently from STAR, although it is unclear whether mothers will benefit more because their family demands are greater or fathers will benefit more because their work-family needs were not previously recognized or they had not pursued the marginalized flexible work options.

Previous research also leads us to expect that employees with fewer work resources at baseline, i.e., those who report less schedule control and less supportive supervisors, will benefit more from STAR because they were more vulnerable to begin with. STAR may “level the playing field” by raising these employees’ sense of schedule control and supervisor support to match that reported by their peers whose supervisors had previously been flexible and supportive. Employees with high work demands are also expected to be more vulnerable to work-family conflict and so benefit more from the intervention. However, it is unclear how increased schedule control and supervisor support – the work resources hypothesized to ameliorate work-family conflict – stack up against high work demands in the form of very long work hours or perceived job pressures (Blair-Loy 2009, Kelly et al. 2011, Schieman et al. 2009).

We also investigate whether STAR benefits those with existing vulnerability as indicated by higher work-to-family and family-to-work conflict at baseline. Employees with high conflict at baseline may receive more benefit in part because they have more room for improvement. STAR may be more salient and attractive to employees with high work-family conflict (Hammer et al. 2011), even though the initiative is not presented to employees explicitly as a work-family initiative.

It is also plausible that STAR brings benefits to parents and adult caregivers, but shifts burdens to employees whose non-work obligations are less extensive or obvious. If this is the case, employees with no dependents may experience more work-family conflicts under STAR or begin working longer hours or more intensely as their peers take advantage of the initiative. The popular and business press are attuned to the possibility of work-family backlash prompted by singles and those without dependents taking on even more work as parents and adult caregivers attend to family needs (e.g., Shellenbarger 2012, Wells 2007), though there is little research evidence to date (cf. Casper, Weltman, and Kweisga 2007).

METHODS

Research Site and Interest in the STAR Intervention

This field experiment was conducted in the information technology (IT) division of a U.S. Fortune 500 organization. Division employees developed software, tested applications, responded to problems in applications and related networks, worked with clients to plan how applications could meet their needs, and worked as project managers and administrative staff. Formative research indicated that the organization had fairly traditional expectations for employees, who attempted to prove themselves as serious, dedicated, and committed by working long hours, prioritizing work over family, pursuing uninterrupted professional careers, and traveling as requested. Historically, employees received generous benefits and good wages in return. Mean tenure was over 10 years.

As the organization grew over the last ten years, the organization came to rely on technology to coordinate projects. Many work groups are not “co-located” in the same building, city, or state. Additionally, since about 2005, some employees have worked closely with offshore employees and contractors (primarily in India). Many U.S. employees are expected to be available for questions from their offshore collaborators at any hour and routinely participate in early morning conference calls – usually from home – to coordinate work. Approximately 20 percent of employees had a supervisor in a different state at the time of the baseline survey. Clearly, remote work and coordination across time zones was happening even before STAR was introduced to some groups.

Formative research revealed wide variation in managers’ acceptance of variable schedules and working at home, especially when employees did so to meet personal or family obligations rather than in response to work demands (Leslie et al. 2012). Some employees expressed frustration with the variation in managers’ approaches, expectations, and application of the company’s telecommuting policy. Prior managerial discretion meant some employees experienced the STAR intervention as an opportunity to implement new practices and others saw it as an endorsement of practices that were already happening informally. Our analysis examines whether effects were greater or smaller depending on baseline schedule control and supervisor support.

Decision-makers, both human resources managers and IT executives, were interested in STAR for several reasons. They recognized that coordination with offshore staff meant many U.S. employees were working longer or more variable hours, with the possibility of burnout and increased turnover. Executives had also heard the frustrations of employees after one vice president clamped down on remote work. Insiders recognized that the firm was not seen as particularly innovative and hoped that changes would attract applicants from newer, smaller firms. Work-family conflict was not presented as a central concern by leadership, although there was recognition that employees with family responsibilities and high work demands were especially vulnerable to burnout. Executives also expressed interest in the possibility that improving work conditions might improve employees’ health, and perhaps help contain health care costs, but that did not seem to be the initial motivation.

The researchers selected this organization from possible industry partners because the organization offered multiple work units sufficient to support random assignment, geographic proximity to minimize study personnel travel distance between locations, site and workforce stability to support the research for the study duration, and specific endorsement from the IT executives to support all research activities.

Development and Delivery of STAR Intervention

STAR was developed jointly by researchers and outside consultants. Drawing on formative research in the company and the two intervention studies reviewed above, the researchers and consultants worked together to customize the intervention materials for this workforce. Computer-based training on supervisor support for family and personal life was customized to include appropriate examples of managers’ support for professional development (e.g. asking employee about adequacy of tools or resources and providing help as needed) as well as a video message from the top IT executive endorsing STAR. Participatory training sessions were customized by including IT-relevant discussions of communicating by instant messenger, coordinating with offshore staff, and handling periods of high demands around software releases. The intervention is described further in Kossek et al. (2012) and materials are available, at no cost, at workfamilyhealthnetwork.org.

STAR was rolled out as a company-sponsored pilot program announced by IT executives. It is common within the IT division to pilot new initiatives, including those developed in-house and those brought in by consultants. The company provided executive sponsorship, human resources staff time, space for training, and allowed participants to attend STAR sessions and complete related activities during the workday. Four facilitators delivered STAR training at TOMO; they were supported by research grants but were not identified with the researchers within the company. Additional STAR coordinators scheduled sessions, computer-based training, and self-monitoring activities, observed training, and later conducted interviews to learn how STAR was implemented; this was a hybrid role with some research elements, but the outside facilitators served as the primary face of STAR. The separation of STAR and the broader study was not complete, because top IT executives, human resources managers, and a small advisory board knew of the link; however, we pursued this strategy to try to avoid differential participation in the study by the control group and to ensure that the core data for the evaluation was collected by research staff who were “blind” to the employees’ condition (i.e., STAR or control).

Randomization

The randomization process began by identifying groups of employees and managers who would be treated as “study groups.” 56 study groups were identified in close coordination with company representatives. Some study groups are large teams of workers reporting to the same manager, while other study groups include multiple teams who either report to the same senior leadership or work closely together on the same application. We refer to these units as study groups to denote that they are aggregations of work groups that operate in the organization.

Company representatives and our formative research suggested that study findings would be discounted if all or most of the groups receiving the intervention were in a single job function, reported to any one VP, or represented particularly small or particularly large work groups. For example, if all the groups randomized to STAR happened to be software development teams, managers and employees in other job functions would likely view the findings as irrelevant to them. We therefore decided on a randomization design that would ensure balance on job function, VP, and size of the study group. We modified a biased-coin randomization technique for use with group randomization (Frane 1998, Bray et al. 2013). The first four study groups were randomized using simple randomization. Subsequent study groups were hypothetically assigned to intervention and then the null hypothesis of balance across study conditions (i.e., intervention or usual practice control) was tested for each randomization criterion (i.e., job function, size of study group, VP) separately; each group was then hypothetically assigned to usual practice. The lowest p-value derived from the balance test across randomization criteria was used in adaptive randomization procedures, to minimize risk of imbalance.

Study Recruitment and Data Collection

Employees were eligible to participate in the study if they were employees (not contractors) located in the two cities where data collection occurred. Additionally, one study group whose employees are represented by collective bargaining agreements was excluded because of concerns that the intervention might conflict with contractual work rules. Recruitment materials emphasized the value of a study investigating the connections between employees’ work, family, and health for the employees (who received some health information), the employing organization, and scientific knowledge more broadly; there was no reference to STAR. Recruitment materials emphasized the independence of the research team from TOMO and the confidentiality of individual data. Computer-assisted personal interviews, lasting approximately 60 minutes, were conducted at the workplace on company time, at baseline and six months later.

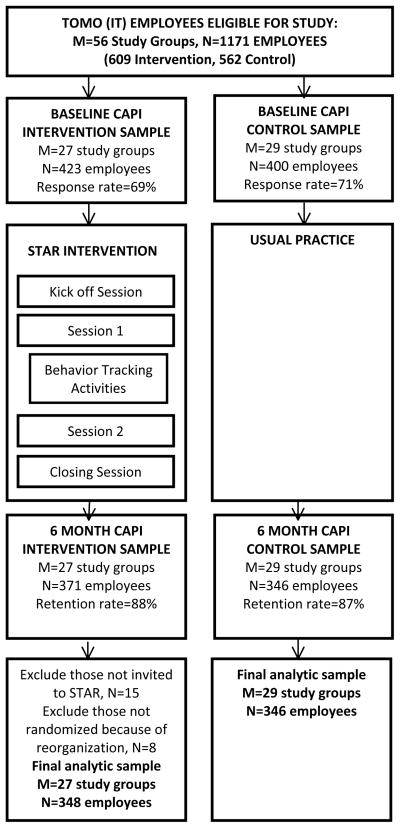

At baseline, 70 percent of eligible employees participated (N=823) and 87 percent of baseline participants completed the six-month follow-up (N=717). Figure 1 confirms that response rates are similar for employees in intervention and control conditions and that all study groups identified as eligible for the study were randomized and had some employees who participated. Analyses are conducted on the respondents who completed both baseline and six-month surveys with the following exclusions. Fifteen employees who were randomized to the intervention condition but never invited to participate in STAR sessions because of an error by staff are excluded from this analysis. Additionally, eight employees are excluded because they shifted reporting structures and began reporting to a manager already going through STAR. The resulting analytic sample consists of 694 employees nested in 56 study groups. See the Online Supplement (Appendix Table A) for analyses of response bias and baseline means by condition to confirm balance (i.e. that randomization worked to create comparable groups and therefore we can analyze the effects of STAR without needing to adjust for individual characteristics).

Figure 1.

Study Design and Response Rates

Appendix Table A.

Baseline Characteristics by Condition, at Individual Level

| STAR

|

Control

|

Mean Difference between STAR and Control: (1) - | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (1) | Median | StdDev | Min | Max | N | Mean (2) | Median | StdDev | Min | Max | ||

| Work-Family Outcomes and Work Environment | |||||||||||||

| Schedule Control (1–5) | 348 | 3.56 | 3.54 | 0.7 | 1.14 | 5 | 346 | 3.63 | 3.63 | 0.65 | 1.88 | 5 | −0.07 |

| Supervisor Support for Family/Personal Life (1–5) | 347 | 3.85 | 4 | 0.82 | 1 | 5 | 343 | 3.85 | 4 | 0.81 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Work-to-Family Conflict (1–5) | 348 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 0.95 | 1 | 5 | 346 | 3.05 | 3 | 0.94 | 1 | 5 | 0.05 |

| Family-to-Work Conflict (1–5) | 348 | 2.15 | 2 | 0.63 | 1 | 4.2 | 346 | 2.08 | 2 | 0.65 | 1 | 4.4 | 0.07 |

| Enough Time for Family | 344 | 3.41 | 3 | 0.78 | 1 | 5 | 333 | 3.50 | 4 | 0.74 | 1 | 5 | −0.09 |

| Work Hours | 348 | 45.36 | 45 | 5.57 | 5 | 70 | 346 | 45.43 | 45 | 5.75 | 30 | 70 | −0.07 |

| Work Hours >= 50 | 348 | 0.28 | 0 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.29 | 0 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 | −0.01 |

| Psychological Job Demands Scale (1–5) | 348 | 3.62 | 3.67 | 0.7 | 1.67 | 5 | 346 | 3.54 | 3.67 | 0.71 | 1.67 | 5 | 0.08 |

| Company Tenure (in years) | 348 | 14.3 | 10 | 9.61 | 0 | 42 | 346 | 12.76 | 10 | 8.57 | 0 | 42 | 1.54 |

| Decision Authority (1–5) | 347 | 3.8 | 4 | 0.73 | 1 | 5 | 343 | 3.86 | 4 | 0.66 | 1 | 5 | −0.06 |

| Job Insecurity (1–4) | 341 | 2.33 | 2 | 0.74 | 1 | 4 | 337 | 2.27 | 2 | 0.74 | 1 | 4 | 0.06 |

| Baseline Survey after Merger Announcement | 348 | 0.46 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.46 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Demographics and Family Demands | |||||||||||||

| Age | 348 | 46.17 | 46.5 | 9.15 | 25 | 70 | 345 | 45.88 | 46 | 8.67 | 24 | 70 | 0.29 |

| Female | 348 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.37 | 0 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | 0.03 |

| Race | |||||||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 348 | 0.69 | 1 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.69 | 1 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Asian Indian | 348 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.17 | 0 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 | −0.04 |

| Other Asian and Other Pacific Islander | 348 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.24 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Hispanic | 348 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.26 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 | 0.02 |

| Black, Other, and More than one race | 348 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.21 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.18 | 0 | 1 | 0.02 |

| Married/Partnered | 348 | 0.81 | 1 | 0.39 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 0.01 |

| No children at home | 348 | 0.53 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.53 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Fathers | 348 | 0.27 | 0 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.32 | 0 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 | −0.05 |

| Mothers | 348 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.15 | 0 | 0.36 | 0 | 1 | 0.05 |

| Number of children living in respondent’s home for 4 or more days/week | 348 | 0.78 | 0 | 0.97 | 0 | 5 | 346 | 0.81 | 0 | 1.05 | 0 | 8 | −0.03 |

| Child with disability or chronic illness | 199 | 0.12 | 0 | 0.32 | 0 | 1 | 192 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.29 | 0 | 1 | 0.03 |

| Single Parents | 348 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.21 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.18 | 0 | 1 | 0.02 |

| Respondent does care for adult relative | 348 | 0.23 | 0 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 | 346 | 0.23 | 0 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Note 1: The unit of analysis for these results is person-wave. Employees are restricted to those (1) who completed both wave 1 and wave 2 CAPI, (2) excluding 15 employees in work groups 56b, 56b.1, 56b.2, and 56b.3, and (3) excluding 8 employees in work group 14a.3 for whom we do not have randomization-related variables. N = 694.

Note 2: For scales, mean is imputed from other responses by the same respondent to other questions in the scale and it is only imputed if the respondent answered 75% or more of the questions in the scale.

MEASURES

Outcomes

For all scales analyzed as outcomes, Table 1 provides wording of items, source, range, reliability scores, and response values. Schedule Control measures the degree to which employees report control over their work time and work location.3 Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB) is designed to measure employee perceptions of supervisors’ behavioral support for family and personal life. It is a separate construct from general supervisor support, as some supervisors are supportive of employees’ job concerns, but not of employees’ family concerns. We use a 4-item version, with questions measuring emotional support, instrumental support, role modeling, and creative management, validated by Hammer and colleagues (2013). Work-to-Family Conflict and Family-to-Work Conflict reflect the degree to which role responsibilities from one domain are incompatible with the other. Time Adequacy with Family asks employees whether they have had enough time during the past year to spend with their family. Weekly Hours Worked is measured with a single question: “About how many hours do you work in a typical week in this job?” The mean at baseline is 45 hours, with 29 percent reporting working over 50 hours per week. Psychological Job Demands is a subscale of the Karasek and Theorell (1990) demands-control model measuring perceived pressure and overload.

Table 1.

Description of Scales

| Scale | Source | Variable Description | Cronbach’s Alpha (Wave 1) | Cronbach’s Alpha (Wave 2) | Range | Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schedule Control | Thomas & Ganster 1995 | How much choice do you have over when you take vacations or days off? How much choice do you have over when you can take off a few hours? How much choice do you have over when you begin and end each work day? How much choice do you have over the total number of hours you work each week? How much choice do you have over doing some of your work at home or at another location, instead of [insert company name/location]? How much choice do you have over the number of personal phone calls you make or receive while you work? How much choice do you have over the amount or times you take work home with you? How much choice do you have over shifting to a part-time schedule (or full-time if currently part-time) while remaining in your current position if you wanted to do so? |

0.802 | 0.825 | 1–5 | 1 = Very little 2 = Little 3 = A moderate amount 4 = Much 5 = Very much |

| Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors | Hammer et al. 2013 | Your supervisor makes you feel comfortable talking to him/her about your conflicts between work and non-work. Your supervisor works effectively with employees to creatively solve conflicts between work and non-work. Your supervisor demonstrates effective behaviors in how to juggle work and non-work issues. Your supervisor organizes the work in your department or unit to jointly benefit employees and the company. |

0.874 | 0.876 | 1–5 | 1 = Strongly Diagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neither 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree |

| Work-to-Family Conflict | Netemeyer et al. 1996 | The demands of your work interfere with your family or personal time. The amount of time your job takes up makes it difficult to fulfill your family or personal responsibilities. Things you want to do at home do not get done because of the demands your job puts on you. Your job produces strain that makes it difficult to fulfill your family or personal duties. Due to your work-related duties, you have to make changes to your plans for family or personal activities. |

0.915 | 0.914 | 1–5 | 1 = Strongly Diagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neither 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree |

| Family-to-Work Conflict | Netemeyer et al. 1996 | The demands of your family or personal relationships interfere with work-related activities. You have to put off doing things at work because of demands on your time at home. Things you want to do at work don’t get done because of the demands of your family or personal life. Your home life interferes with your responsibilities at work, such as getting to work on time, accomplishing daily tasks, and working overtime. Family-related strain interferes with your ability to perform job-related duties. |

0.835 | 0.863 | 1–5 | 1 = Strongly Diagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neither 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree |

| Psychological Job Demands | Karasek et al. 1998 | You do not have enough time to get your job done. Your job requires very fast work. Your job requires very hard work. |

0.575 | 0.581 | 1–5 | 1 = Strongly Diagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neither 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree |

Note 1: Employees are restricted to those (1) who completed both wave 1 and wave 2 CAPI, (2) excluding 15 employees in work groups 56b, 56b.1, 56b.2, and 56b.3, and (3) excluding 8 employees in work group 14a.3 for whom we do not have randomization-related variables.

If a respondent skipped a specific item but completed at least 75 percent of the scale (e.g., 4 out of 5 items in work-to-family conflict scale), we assign the mean from other responses by the same respondent to other questions in that scale. If the respondent did not complete at least 75 percent of the scale (or did not complete the time adequacy item or the job demands scale), they are omitted from that model.

Variables for Subgroup Analyses

The subgroup analyses investigate whether employees with greater vulnerability to work-family conflict, as measured by high family demands, low work resources, and more conflict at baseline, benefit more from STAR. Child at Home is an indicator of parents (or stepparents) with children under 18 living in their home at least four days per week. Both childless employees and parents with grown children or children who do not live in their homes are coded as Child Not at Home. We investigated different effects for mothers and fathers by interacting gender and Child at Home (n=121 mothers, 205 fathers). We also created four categories of family demands: Child at Home Only (n=261) for those with children at home but no adult care reported, Care for Adults for those reporting adult caregiving responsibilities at least 3 hours per week but no children under 18 at home, n=95), Child at Home and Care for Adults (“sandwich generation,” n=65), and employees with No Dependents (n=273) reported. Those with no dependents may have a spouse or an adult child (not receiving care) living in the home. Low Schedule Control (n=122) is indicated by a mean response of “very little” or “little” choice over one’s schedule (i.e., mean <3 at baseline). Lower Supervisor Support (n=308) reflects strong disagreement, disagreement, or neutral responses to affirmative statements about the supervisor’s support for family and personal life (i.e., mean <4 at baseline); we included the neutral responses here because relatively few employees (n=84) disagreed outright with the affirmative statements regarding supervisor support. High Work-to-Family Conflict (n=147) captured those who agreed or strongly agreed that work interfered with family and personal life at baseline (i.e., mean >=4). Family-to-work conflict is much less common; only 86 employees strongly agreed, agreed, or said they neither agreed nor disagreed that family interfered with work (coded Higher Family-to-Work Conflict if mean >3). The skewed distribution of family-to-work conflict is not surprising given previous research and the cultural expectation that professional workers will organize their lives around work (Blair-Loy 2003; Jacobs and Gerson 2004). To assess whether STAR brings benefits to those with especially high work demands, we compared employees working 50 or more hours (n=200) with those working fewer than 50 (n=494) (Schieman et al. 2009, Cha 2010) and dichotomized High Psychological Job Demands (n=253) at the mean >=4, indicating responses of agreement or strongly agreement that the job requires very hard work, very fast work, and not having enough time to do the job.

ANALYSIS

We estimate generalized linear mixed models (using PROC MIXED in SAS) on repeated measures with random effects for the level-2 unit nested in experimental condition, i.e., for study groups in STAR or usual practice. This is a member cohort analysis, utilizing pre- and post- data on individuals nested in study groups (Murray 1998). Specifically, mixed models of the following form are used to assess the effect of the intervention on outcomes.

| (1) |

Here Yij:k:l is the outcome for person i observed at time j, nested within group k, which is in condition l; f(·) is a link function; and εij:k:l is an iid error or residual; here we estimate linear models. The βs are fixed-effect parameters to be estimated and the γs are random-effect parameters (i.e., variance components) to be estimated. Cl is a dichotomous variable indicating membership in the STAR intervention condition, Tj is a dichotomous variable indicating the jth time point, TjCl is the interaction between condition and time (here STAR*Wave 2). Xij:k:l is a vector of demographic and other potential confounds; none are included here because randomization created balance on potential confounds. RANDk is a vector of randomization factors used in the biased coin algorithm, i.e. job function and study group size. These are included as control variables. Gk:l is a vector indicating group membership, Mi:k:l is a vector of individual indicators, and TGjk:l is a vector of interactions between time points and group membership. Given the specification of the fixed effects, β3 captures the effect of the intervention at that follow-up time point (Murray 1998) and can be thought of as the difference-in-difference estimate.

Our central analyses employ an intent-to-treat framework that provides a conservative estimate of the intervention effect. This means all employees eligible for receiving the treatment are coded as being in the STAR condition, even though individuals in STAR-randomized study groups decided how much to participate in the training. Sessions were held during work hours and mean attendance rate for the analytic sample was 74 percent of sessions. 10.4% percent of employees (n=37) attended fewer than half of the STAR sessions, and 3.9% (n=14) of those randomized to STAR attended none of the sessions. Supplemental analyses move beyond the intent-to-treat framework by comparing the effects of STAR for employees with high and lower participation.

RESULTS

Findings on Central Research Questions

We first investigate whether STAR improves work resources for managing work-family challenges. STAR increases both employees’ schedule control and supervisor support for family and personal life significantly, compared to changes in the control groups, providing an affirmative answer to our first research question. In Table 2, the STAR*Wave 2 coefficient (bolded) is the intervention (or treatment) effect of interest with a difference-in-difference interpretation. Other covariates include condition, time point, study group size, and core job function. Table 3 presents standardized effect sizes calculated by dividing the STAR*Wave2 coefficient (from Table 2) by the standard deviation of the outcome at baseline. Employees in STAR perceive more control over where and when they work and describe their supervisors as more supportive of their personal lives. These changes in employees’ perceptions of their work environment are striking since neither the practical requirements of employees’ jobs nor the person or personality of their managers changed; instead STAR shifted employees’ sense of what was possible and what was supported in the same job and social context.

Table 2.

Multilevel Intervention Effects on Work-Family Outcomes

| Schedule Control (M = 56 study groups, N = 1388 person-waves) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | DF | t Value | Pr > |t| | |

| STAR | −0.092 | 0.079 | 52 | −1.17 | 0.247 |

| Wave 2 | 0.035 | 0.029 | 54 | 1.20 | 0.235 |

| STAR*Wave 2 | 0.231 | 0.041 | 54 | 5.63 | <.0001 |

| #Employees for Randomization | 0.005 | 0.003 | 52 | 1.45 | 0.152 |

| Core Function (see Note 3) | 0.006 | 0.076 | 52 | 0.08 | 0.939 |

| Intercept | 3.505 | 0.096 | 52 | 36.60 | <.0001 |

| Subject | Ratio | Estimate | |||

| Intercept | studygroup(star) | 0.316 | 0.046 | ||

| CS | ID(studygroup*star) | 1.782 | 0.261 | ||

| Residual | 1 | 0.146 | |||

| −2 Res Log Likelihood | AIC | AICC | BIC | ||

| 2403.8 | 2409.8 | 2409.9 | 2415.9 | ||

| Work-to-Family Conflict (M = 56 study groups, N = 1388 person-waves) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | DF | t Value | Pr > |t| | |

| STAR | 0.106 | 0.117 | 52 | 0.91 | 0.366 |

| Wave 2 | −0.103 | 0.043 | 54 | −2.42 | 0.019 |

| STAR*Wave 2 | −0.116 | 0.060 | 54 | −1.93 | 0.059 |

| #Employees for Randomization | −0.006 | 0.005 | 52 | −1.22 | 0.226 |

| Core Function | −0.024 | 0.114 | 52 | −0.21 | 0.834 |

| Intercept | 3.181 | 0.142 | 52 | 22.44 | <.0001 |

| Subject | Ratio | Estimate | |||

| Intercept | studygroup(star) | 0.360 | 0.113 | ||

| CS | ID(studygroup*star) | 1.423 | 0.447 | ||

| Residual | 1 | 0.314 | |||

| −2 Res Log Likelihood | AIC | AICC | BIC | ||

| 3350.8 | 3356.8 | 3356.9 | 3362.9 | ||

| Enough Time for Family (M = 56 study groups, N = 1360 person-waves) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | DF | t Value | Pr > |t| | |

| STAR | −0.092 | 0.069 | 52 | −1.34 | 0.187 |

| Wave 2 | −0.039 | 0.042 | 54 | −0.92 | 0.360 |

| STAR*Wave 2 | 0.137 | 0.059 | 54 | 2.32 | 0.024 |

| #Employees for Randomization | −0.001 | 0.002 | 52 | −0.22 | 0.826 |

| Core Function | −0.008 | 0.062 | 52 | −0.12 | 0.902 |

| Intercept | 3.515 | 0.080 | 52 | 43.95 | <.0001 |

| Subject | Ratio | Estimate | |||

| Intercept | studygroup(star) | 0.056 | 0.016 | ||

| CS | ID(studygroup*star) | 0.825 | 0.241 | ||

| Residual | 1 | 0.292 | |||

| −2 Res Log Likelihood | AIC | AICC | BIC | ||

| 2899.7 | 2905.7 | 2905.7 | 2911.8 | ||

| Supervisor Support for Family/Personal Life (M = 56 study groups, N = 1379 person-waves) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | DF | t Value | Pr > |t| | |

| STAR | −0.010 | 0.087 | 52 | −0.12 | 0.908 |

| Wave 2 | −0.063 | 0.037 | 54 | −1.71 | 0.094 |

| STAR*Wave 2 | 0.131 | 0.052 | 54 | 2.51 | 0.015 |

| #Employees for Randomization | −0.001 | 0.003 | 52 | −0.21 | 0.834 |

| Core Function | −0.094 | 0.083 | 52 | −1.13 | 0.264 |

| Intercept | 3.923 | 0.105 | 52 | 37.51 | <.0001 |

| Subject | Ratio | Estimate | |||

| Intercept | studygroup(star) | 0.205 | 0.047 | ||

| CS | ID(studygroup*star) | 1.555 | 0.361 | ||

| Residual | 1 | 0.232 | |||

| −2 Res Log Likelihood | AIC | AICC | BIC | ||

| 2940.5 | 2946.5 | 2946.5 | 2952.5 | ||

| Family-to-Work Conflict (M = 56 study groups, N = 1388 person-waves) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | DF | t Value | Pr > |t| | |

| STAR | 0.088 | 0.060 | 52 | 1.47 | 0.147 |

| Wave 2 | 0.030 | 0.030 | 54 | 1.00 | 0.320 |

| STAR*Wave 2 | −0.088 | 0.043 | 54 | −2.05 | 0.045 |

| #Employees for Randomization | 0.001 | 0.002 | 52 | 0.31 | 0.756 |

| Core Function | 0.117 | 0.055 | 52 | 2.11 | 0.040 |

| Intercept | 1.999 | 0.071 | 52 | 28.20 | <.0001 |

| Subject | Ratio | Estimate | |||

| Intercept | studygroup(star) | 0.094 | 0.015 | ||

| CS | ID(studygroup*star) | 1.338 | 0.214 | ||

| Residual | 1 | 0.160 | |||

| −2 Res Log Likelihood | AIC | AICC | BIC | ||

| 2349.3 | 2355.3 | 2355.3 | 2361.4 | ||

Note 1: Employees are restricted to those (1) who completed both wave 1 and wave 2 CAPI, (2) excluding 15 employees in work groups 56b, 56b.1, 56b.2, and 56b.3, and (3) excluding 8 employees in work group 14a.3 for whom we do not have randomization-related variables.

Note 2: For scales, mean is imputed from other responses by the same respondent to other questions in the scale and it is only imputed if the respondent answered 75% or more of the questions in the scale.

Note 3: The core function identifies groups where most individuals were involved in software development with groups dominated by other IT job functions as reference group.

Table 3.

Intervention Effect Sizes

| Outcomes: | Estimate | Effect Size | Pr > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schedule Control | 0.231 | 0.342 | <.0001 |

| Supervisor Support for Family/Personal Life | 0.131 | 0.160 | 0.015 |

| Work-to-Family Conflict | −0.116 | 0.122 | 0.059 |

| Family-to-Work Conflict | −0.088 | 0.138 | 0.045 |

| Enough Time for Family | 0.137 | 0.179 | 0.024 |

| Work Hours | −0.263 | 0.047 | 0.482 |

| Psychological Job Demands | −0.075 | 0.107 | 0.106 |

Note 1: Effect size is STAR*Wave2 coefficient from Tables 2 (and parallel models for hours and job demands) divided by the standard deviation of the outcome at baseline.

In addition to evaluating whether employees’ sense of the control and support available to them changed, we can also assess whether their work practices changed. We find that STAR encouraged employees to adjust their schedules based on personal needs and to work at home more. Employees in STAR were twice as likely to describe their schedule as “variable” at the six-months survey, going from 17% to 35%. 21% of employees in the usual practice group reported a variable schedule at both waves. In questions asked only on the six-month survey, STAR respondents were significantly more likely than usual-practice employees to agree that they “fit in personal errands and appointments during work hours” and “change schedule as needed for personal/family life.” Finally, mean hours of work at home almost doubled for STAR employees between the surveys (from 10.2 to 19.6 hours per week), while increasing significantly less for employees in usual practice groups (from 10.8 to 12.3 hours per week). These findings provide evidence that schedule control was both perceived and enacted by employees in STAR.

Second, we find that all three measures of the work-family interface improve more for the employees in STAR than those in usual practice control groups. The intervention effect for work-to-family conflict is marginally significant (p=.059) in these models and we see a statistically significant intervention effect for family-to-work conflict. STAR also significantly increases reported time adequacy with family members. Again, STAR produced changes in work-family conflict and time adequacy while employees continued in the same jobs – many with the same long hours and work pressures – and in the same family situations. These findings provide clear evidence that what the expectations, interactions, and practices in a workplace affect employees’ wellbeing, in the form of work-family conflict, directly and in ways not dictated by the work itself.

For our third research question, we turn to models investigating whether STAR has negative consequences by increasing work hours or psychological job demands. Employees might experience work intensification as an unintended byproduct of STAR increasing the permeability of work and nonwork across time and space; this would be the double-edged sword of workplace flexibility (Blair-Loy 2009, Perlow 2012, Schieman et al. 2009). Table 3 shows there is no evidence that this occurred. In fact, STAR respondents are less likely to agree with the single item (from the job demands scale) stating “You do not have enough time to get your job done,” at a marginally significant (p=.06) level. This finding suggests that the intervention relieved time pressures for employees (at work as well as with family time, seen previously) and contradicts the work intensification hypothesis.4 More generally, Table 3 provides evidence that STAR’s effects are larger for the outcomes directly targeted by the intervention. Schedule control moves the most, with modest but significant increases in family-supportive supervision and adequate time for family as well.

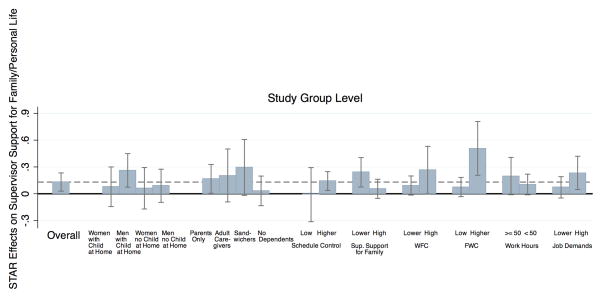

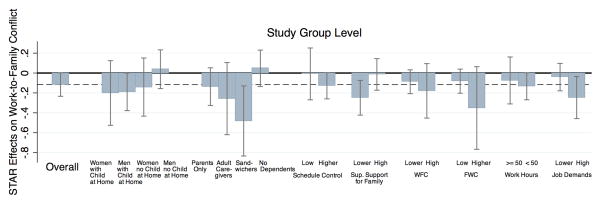

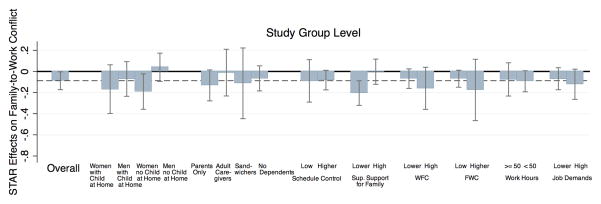

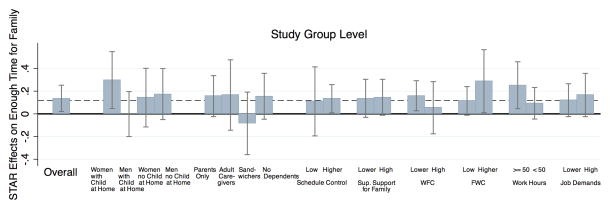

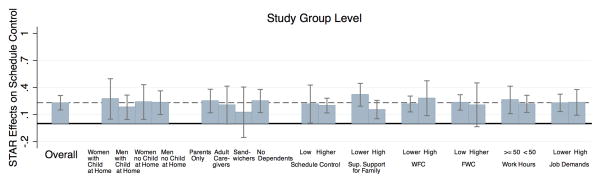

Our fourth research question considers whether employees with greater expected vulnerability to work-family conflicts experience more benefits from the intervention. We operationalize vulnerability as higher family demands, lower work resources at baseline, work-family interference reported at baseline, and high work demands that might overwhelm any positive changes that come with STAR. Figures 2a–2e show the intervention effect (STAR*Wave 2 coefficient) for the unstratified models with the full sample (see Table 2) and then intervention effects for stratified models estimated separately for each subgroup. The overall intervention effect for the full study population is marked with a dotted horizontal line, with confidence intervals from subgroup models shown with bars. Appendix Table B provides more detail.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a: Intervention Effects for Schedule Control, by Subgroups

Figure 2b: Intervention Effects for Sup. Support for Family, by Subgroups

Figure 2c: Intervention Effects for Work-to-Family Conflict, by Subgroups

Figure 2d: Intervention Effects for Family-to-Work Conflict, by Subgroups

Figure 2e: Intervention Effects for Enough Time for Family, by Subgroups

Appendix Table B.

Summary of Intervention Effects for Different Subgroups

| Stratified by: | Work-Family Outcomes

|

Work Intensification Outcomes

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schedule Control

|

Supervisor Support for Family/Personal Life

|

Work-to-Family Conflict

|

Family-to-Work Conflict

|

Enough Time for Family

|

Work Hours

|

Job Demands

|

|||||||||||||||

| Estimate | DF | P- value | Estimate | DF | P- value | Estimate | DF | P- value | Estimate | DF | P- value | Estimate | DF | P- value | Estimate | DF | P- value | Estimate | DF | P- value | |

| UNSTRATIFIED ESTIMATE | 0.231 | 54 | <.0001 | 0.131 | 54 | 0.015 | −0.116 | 54 | 0.059 | −0.088 | 54 | 0.045 | 0.137 | 54 | 0.024 | −0.263 | 54 | 0.482 | −0.075 | 54 | 0.106 |

| Parents with Child at Home | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Women (N = 121) | 0.273 | 38 | 0.022 | 0.078 | 38 | 0.495 | −0.201 | 38 | 0.233 | −0.167 | 38 | 0.163 | 0.298 | 38 | 0.025 | −1.459 | 38 | 0.155 | −0.085 | 38 | 0.418 |

| Men (N= 205) | 0.181 | 53 | 0.012 | 0.261 | 52 | 0.009 | −0.189 | 53 | 0.055 | −0.071 | 53 | 0.401 | −0.002 | 51 | 0.986 | −1.070 | 53 | 0.066 | −0.032 | 53 | 0.710 |

| No Child (or none at home) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Women (N = 146) | 0.239 | 41 | 0.019 | 0.061 | 41 | 0.607 | −0.141 | 41 | 0.350 | −0.190 | 41 | 0.031 | 0.143 | 40 | 0.285 | 0.550 | 41 | 0.591 | −0.008 | 41 | 0.938 |

| Men (N= 222) | 0.231 | 50 | 0.001 | 0.089 | 50 | 0.352 | 0.038 | 50 | 0.702 | 0.039 | 50 | 0.567 | 0.174 | 50 | 0.136 | 0.654 | 50 | 0.260 | −0.163 | 50 | 0.063 |

| Child at Home Only (N = 261) | 0.250 | 54 | <.001 | 0.167 | 54 | 0.048 | −0.137 | 54 | 0.162 | −0.132 | 54 | 0.083 | 0.156 | 52 | 0.096 | −1.142 | 54 | 0.026 | −0.013 | 54 | 0.859 |

| Care for Adults Only (N = 95) | 0.205 | 42 | 0.064 | 0.205 | 42 | 0.183 | −0.257 | 42 | 0.172 | −0.011 | 42 | 0.923 | 0.166 | 42 | 0.300 | 1.362 | 42 | 0.363 | −0.137 | 42 | 0.364 |

| Child at Home and Care for Adults (N = 65) | 0.125 | 36 | 0.388 | 0.295 | 36 | 0.073 | −0.482 | 36 | 0.011 | −0.112 | 36 | 0.514 | −0.084 | 36 | 0.553 | −1.510 | 36 | 0.358 | −0.178 | 36 | 0.203 |

| No Dependents (N = 273) | 0.250 | 54 | <.001 | 0.032 | 54 | 0.707 | 0.048 | 54 | 0.613 | −0.065 | 54 | 0.284 | 0.155 | 53 | 0.138 | 0.310 | 54 | 0.536 | −0.087 | 54 | 0.218 |

| Low Schedule Control (< 3) (N = 122) | 0.217 | 41 | 0.050 | −0.010 | 41 | 0.948 | −0.009 | 41 | 0.947 | −0.089 | 41 | 0.390 | 0.110 | 41 | 0.483 | −0.354 | 41 | 0.710 | 0.024 | 41 | 0.852 |

| Higher Schedule Control (>=3 ) (N = 572) | 0.200 | 54 | <.0001 | 0.142 | 54 | 0.011 | −0.128 | 54 | 0.064 | −0.082 | 54 | 0.091 | 0.133 | 54 | 0.040 | −0.226 | 54 | 0.579 | −0.092 | 54 | 0.067 |

| Lower Supervisor Support for Family/Personal Life (< 4) (N = 308) | 0.319 | 52 | <.0001 | 0.240 | 52 | 0.006 | −0.248 | 52 | 0.007 | −0.205 | 52 | 0.001 | 0.137 | 52 | 0.115 | −0.098 | 52 | 0.877 | −0.026 | 52 | 0.727 |

| High Supervisor Support for Family/Personal Life (>= 4) (N = 382) | 0.155 | 54 | 0.004 | 0.055 | 54 | 0.318 | −0.014 | 54 | 0.865 | −0.002 | 54 | 0.970 | 0.146 | 54 | 0.076 | −0.420 | 54 | 0.347 | −0.112 | 54 | 0.054 |

| Lower Work-to-Family Conflict (< 4) (N = 547) | 0.217 | 54 | <.0001 | 0.092 | 54 | 0.098 | −0.088 | 54 | 0.157 | −0.068 | 54 | 0.155 | 0.159 | 54 | 0.022 | −0.486 | 54 | 0.222 | −0.071 | 54 | 0.158 |

| High Work-to-Family Conflict (>= 4) (N = 147) | 0.281 | 46 | 0.007 | 0.265 | 46 | 0.057 | −0.179 | 46 | 0.206 | −0.160 | 46 | 0.123 | 0.054 | 46 | 0.648 | 0.664 | 46 | 0.484 | −0.081 | 46 | 0.467 |

| Low Family-to-Work Conflict (< 3) (N = 608) | 0.235 | 54 | <.0001 | 0.075 | 54 | 0.174 | −0.082 | 54 | 0.192 | −0.069 | 54 | 0.102 | 0.114 | 54 | 0.081 | −0.240 | 54 | 0.525 | −0.055 | 54 | 0.250 |

| Higher Family-to-Work Conflict (>= 3) (N = 86) | 0.208 | 33 | 0.103 | 0.508 | 33 | 0.002 | −0.351 | 33 | 0.107 | −0.175 | 33 | 0.246 | 0.287 | 32 | 0.051 | −0.486 | 33 | 0.735 | −0.212 | 33 | 0.181 |

| Work Hours >= 50 (N = 200) | 0.262 | 47 | 0.002 | 0.198 | 47 | 0.069 | −0.075 | 47 | 0.538 | −0.075 | 47 | 0.353 | 0.252 | 47 | 0.021 | 0.859 | 47 | 0.213 | −0.099 | 47 | 0.264 |

| Work Hours < 50 (N = 494) | 0.219 | 54 | <.0001 | 0.104 | 54 | 0.084 | −0.134 | 54 | 0.058 | −0.093 | 54 | 0.073 | 0.093 | 54 | 0.197 | −0.750 | 54 | 0.077 | −0.066 | 54 | 0.226 |

| Lower Job Demands (< 4) (N = 441) | 0.229 | 54 | <.0001 | 0.072 | 54 | 0.245 | −0.041 | 54 | 0.565 | −0.069 | 54 | 0.199 | 0.120 | 54 | 0.110 | −0.208 | 54 | 0.664 | −0.083 | 54 | 0.104 |

| High Job Demands (>= 4) (N = 253) | 0.235 | 51 | 0.002 | 0.234 | 51 | 0.017 | −0.246 | 51 | 0.027 | −0.121 | 51 | 0.103 | 0.166 | 51 | 0.095 | −0.360 | 51 | 0.548 | −0.060 | 51 | 0.449 |

Note 1: Employees are restricted to those (1) who completed both wave 1 and wave 2 CAPI, (2) excluding 15 employees in work groups 56b, 56b.1, 56b.2, and 56b.3, and (3) excluding 8 employees in work group 14a.3 for whom we do not have randomization-related variables.

Note 2: These estimates come from repeated measures analysis conducted for different subgroups and have adjusted for randomization variables (i.e., number of employees for randomization and study group functions). The coefficients reported here are treatment by time indicator interaction.

Note 3: For scales, mean is imputed from other responses by the same respondent to other questions in the scale and it is only imputed if the respondent answered 75% or more of the questions in the scale.

We find that the effects of STAR on schedule control are of similar magnitude almost across the board (Figure 2a). Consistent increases in schedule control suggest that the intervention benefited employees with all types of family situations and those with lower and higher schedule control at baseline. The effects of STAR on schedule control are somewhat larger for those who did not describe their supervisors as supportive at baseline (intervention effect of 0.32, p<.0001, as compared to .23 in the unstratified model). STAR effects are similar across work hours and job demands categories; this suggests that even those who faced work high demands at baseline felt that STAR gave them more choice over when, where, and how much they worked.

The effects of STAR on supervisor support for family and personal life differ by family status and work resources at baseline (Figure 2b and Appendix Table B). The effects of STAR on supervisor support for family and personal life are notably larger for fathers (.26) and sandwich generation employees with at least one child at home plus adult care responsibilities (0.30, as compared to 0.13 in the unstratified model). Perhaps mothers, whose family responsibilities are often more visible and more normative, receive support from managers regardless of condition, while STAR encourages managers to demonstrate support for others’ family responsibilities. Additionally, employees who reported lower supervisor support, higher work-to-family conflict, or higher family-to-work conflict at baseline saw especially large effects of STAR on supervisor support for family and personal life. STAR also had greater effects on supervisors’ family support among those reporting their jobs were quite demanding.

With regard to work-to-family conflict, there is further evidence that employees with more vulnerability benefit more from STAR (Figure 2c, Appendix Table B). In particular, sandwich generation employees see the largest benefits of STAR with regard to work-to-family conflict; among these employees, the STAR intervention effect is −0.48 (p=.01), as compared to −0.12 for the unstratified model. STAR effects on work-to-family conflict are also larger for employees who did not rate their supervisors as supportive of family at baseline (−0.25, as compared to −0.12 in the unstratified model). In models of family-to-work conflict, it was women who did not have children at home (most of whom did have a spouse or partner) who saw greater effects of STAR (Figure 2d), though STAR mothers’ mean family-to-work conflict also declined.

As seen in Figure 2e, STAR brings larger benefits to mothers with regard to reporting enough family time (intervention effect of 0.30, p=.03 as compared to the unstratified effect of 0.14). Employees putting in more than 50 hours per week at baseline saw somewhat greater increases in time adequacy under STAR (intervention effects of 0.25, p=.02, as compared to 0.14 for the unstratified model), though the effects of STAR on work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict are non-significant among those working long hours (see Appendix Table B).

In sum, employees with greater family demands and fewer work resources (particularly moderate or low supervisor support for family) at baseline experienced greater impacts of STAR. A partial exception is the effect of STAR on schedule control, which is similar across most subgroups. Additionally, the findings suggest that STAR brings some benefits to those working longer hours – by providing greater schedule control, supervisor support for family and personal life, and increasing time adequacy with family – but does not override the effect of long work hours interfering with family and personal life.