Abstract

A 29-year-old male patient presented to eye emergency clinic after noticing a left paracentral scotoma on waking. On direct questioning the patient revealed an episode of vigorous sexual intercourse the preceding evening. During orgasm the valsalva manoeuvre can produce a sudden increase in retinal venous pressure resulting in vessel rupture and haemorrhagic retinopathy. Valsalva retinopathy is managed conservatively and the patient's symptoms resolved spontaneously without intervention. This case report highlights the importance of focused history taking of patients which can thereby obviate the need for further investigations. This case also emphasises the importance of considering sexual activity as a cause of stress-induced pathology.

Background

Despite the universal practice of sexual activity, it remains a subject of social taboo with most finding its discussion of great embarrassment. This embarrassment is global, travelling across languages and cultures and is not absent from the psyche of medical practitioners who often find taking a sexual history difficult and discomforting. Owing to the nature of such histories, patients can find them distressing and a source of shame, and details of sexual history are rarely volunteered by patients themselves.1

By writing this report, we hope to highlight the importance of focused history taking because with certain topics, patients would not necessarily volunteer the history. Furthermore, clinicians should be vigilant and always consider sexual activity as a cause of physiological change which can serve to precipitate multiple stress-induced pathology.

Case presentation

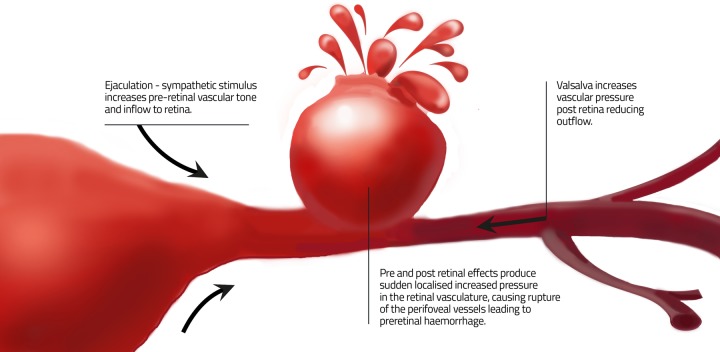

A 29-year-old man presented to the emergency eye clinic reporting an obstruction in the central vision of his left eye, which he had noticed on waking that morning. The visual acuity was 6/6 but visual field testing revealed a paracentral scotoma. Anterior segment examination and pupil reactions were normal. Dilated fundal examination revealed a preretinal haemorrhage (ie, blood trapped beneath the internal limiting membrane and confined anterior to the retina) just superior to the left fovea (figure 1). The patient denied vomiting, coughing, sneezing or constipation immediately prior to the onset of symptoms.

Figure 1.

Valsalva-induced parafoveal haemorrhage.

Investigations

Although the clinical examination was suggestive of valsalva retinopathy, there was no precipitant in the history that would explain the sudden occurrence of the haemorrhage. As a result several investigations were performed, including a fasting blood sugar, clotting screen, and a fundus fluorescein angiogram (FFA). The FFA showed masking due to the haemorrhage but there was no other retinal vascular pathology. All blood tests were normal.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of macular haemorrhage includes diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion, choroidal neovascularisation, retinal artery macroaneurysm, valsalva retinopathy and Terson's syndrome. Of these, it is typically Terson's syndrome and valsalva retinopathy that cause preretinal haemorrhage in the absence of any other vascular pathology.

Treatment

The diagnosis was unclear and the patient was asked to return for follow-up 3 days later. At this visit, he saw a different clinician who asked direct questions about the patient's sexual activity. The patient then reported an episode of vigorous sexual intercourse on the evening preceding the onset of symptoms. This directed history led to the diagnosis of postcoital valsalva retinopathy. Valsalva retinopathy is managed conservatively and is a self-resolving condition with an excellent prognosis.

Outcome and follow-up

The haemorrhage resorbed spontaneously and the scotoma and visual disturbance completely resolved.

Discussion

Most healthcare professionals are unlikely to initiate detailed discussion of a patient's sexual history unless they suspect direct clinical relevance to the patient's presenting symptom.2 However, for some presentations, sexual intercourse may not be immediately obvious as an aetiological factor and clinician reservations in taking a sexual history can lead to delayed diagnosis of relatively benign pathology which does not normally require extensive investigation.3

Obtaining a sexual history can be a source of discomfort and embarrassment to the patient as well as to the clinician.1 Certain issues such as consultation time constraints, confidentiality, cultural and religious differences, fears of intrusion and apparent discrepancy between patient and clinician age and gender can all pose barriers to sexual history taking.4

It has been previously reported that clinicians who take sexual histories regularly are more likely to be comfortable with these issues and therefore less hesitant in taking such histories, but in certain clinical settings, such as the eye clinic, the need for a sexual history is unusual and this can lead it to be neglected or avoided.5

Although medical practitioners do not regularly link sexual activity to ocular disease except for cases involving sexually transmitted infections, popular culture would suggest patients are more aware of sex-induced valsalva retinopathy than physicians with folklore stating that excess masturbation can lead to blindness. Reports of this belief date back hundreds of years with a causal relationship only being investigated in recent years.6

The relationship between sexual activity and retinal haemorrhage was first described in a case series of six patients by Friberg et al6 who also noteworthily mentioned that none of the patients revealed the circumstances through which their vision loss occurred until specifically questioned about predisposing activities that led to the event.

The valsalva manoeuvre is performed by forced expiration against a closed glottis. This manoeuvre produces an increase in intrathoracic pressure with multiple physiological effects including reduced venous return to the heart and a consequent increase in systemic venous pressure. The retinal vasculature is also subject to these effects and significant increases in pressure can cause spontaneous rupture of parafoveal vessels resulting in haemorrhagic retinopathy and sudden loss of vision in one or both eyes. Valsalva retinopathy was first described by Duane in 1975 who contemplated that ocular signs associated with sudden pressure elevations are subject to the force of compression throughout the valsalva manoeuvre and the previous state of the retinal vessels.7 The valsalva manoeuvre is used by the male during sexual intercourse to delay the ejaculatory response. Consequently males might be at higher risk of valsalva retinopathy associated with sexual activity although to our knowledge there is no epidemiological data to confirm this.

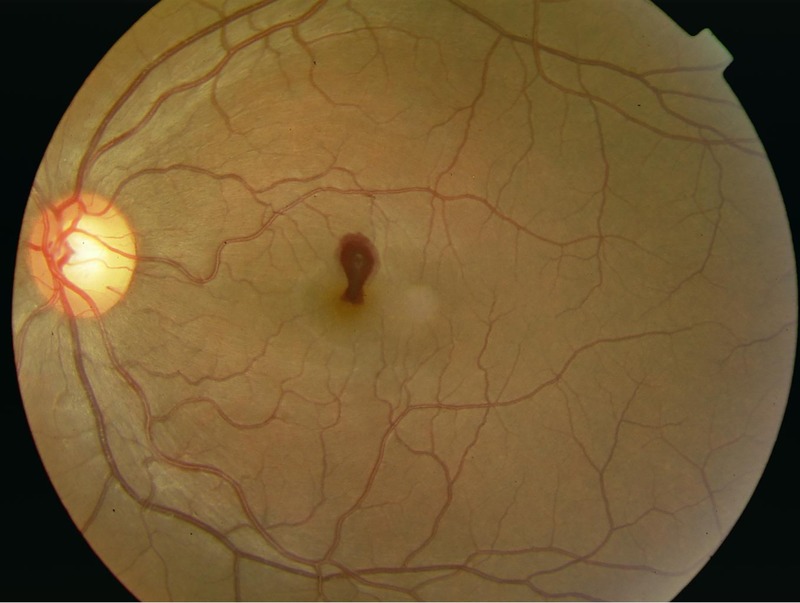

Ejaculation is produced as the coordinated response of the switch from the parasympathetic driven emission phase of ejaculation to the sympathetic driven expulsion phase.8 The autonomic effects of orgasm on the eye are well known and have been associated with other ocular pathology, including angle closure glaucoma.9 During the parasympathetic driven emission phase prior to ejaculation, retinal vascular tone decreases, allowing vessels to dilate and become engorged. Friberg et al6 hypothesised that on orgasm, abrupt increase in sympathetic outflow produces a sudden increase in preretinal vascular tone and pressure which when opposed by reduced venous outflow due to the valsalva manoeuvre can result in such a high elevation in retinal intravascular pressure that the retinal vasculature can rupture causing haemorrhage (figure 2). This is the likely mechanism for post coital valsalva retinopathy.

Learning points.

Focused history taking is of great diagnostic importance because with certain topics, patients will not necessarily volunteer the history.

If a suspicion exists that patient presentation is linked to sexual activity, physicians should be aware of the sensitivities of taking a sexual history and be confident in their ability to do so.

Valsalva retinopathy can be caused by any physical stress, including sexual activity.

Sex-induced valsalva retinopathy has been reported and is thought to be rare but the true incidence is unknown.

Valsalva retinopathy is a self-resolving condition with an excellent prognosis.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism for valsalva retinopathy during orgasm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Matthew Valeras for designing figure 2 graphic.

Footnotes

Contributors: PA and NLT were involved in the clinical management of the patient. PA obtained consent from the patient. LM carried out the literature searches and drafted the case report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Tomlinson J. Taking a sexual history. BMJ 1998;317:1573–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haboubi NHJ, Lincoln N. Views of health professionals on discussing sexual issues with patients. Disabil Rehabil 2003;25:291–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Rubaie K, Arevalo JF. Valsalva retinopathy associated with sexual activity. Case Rep Med 2014;2014:524286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temple-Smith M, Hammond J, Pyett P, et al. Barriers to sexual history taking in general practice. Aust Fam Physician 1996;25(9 Suppl 2):S71–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temple-Smith MJ, Mulvey G, Keogh L. Attitudes to taking a sexual history in general practice in Victoria, Australia. Sex Transm Infect 1999;75:41–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friberg TR, Braunstein RA, Bressler NM. Sudden visual loss associated with sexual activity. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:738–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duane TD. Valsalva hemorrhagic retinopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1972;70:298–313 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coolen LM, Allard J, Truitt WA, et al. Central regulation of ejaculation. Physiol Behav 2004;83:203–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritch R, Dorairaj SK, Liebmann JM. Angle-closure triggered by orgasm: a new provocative test? Eye 2007;21:872–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]