Abstract

Mesenteric vein thrombosis is a rare but potentially lethal cause of abdominal pain. It is usually caused by prothrombotic states that can either be hereditary or acquired. Testosterone supplementation causes an acquired prothrombotic state by promoting erythropoeisis thus causing a secondary polycythaemia. We report a case of a 59-year-old man with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) stage III, who presented with abdominal pain. Evaluation revealed an elevated haemoglobin and haematocrit, a superior mesenteric vein thrombosis on CT and a negative Janus kinase 2 mutation. The patient is currently being treated with 6 months of anticoagulation with rivaroxiban. Although a well-known side effect of testosterone is thrombosis, the present case is used to document in the literature the first case of mesenteric vein thrombosis due to secondary polycythaemia from Androgel in the setting of COPD.

Background

This is the first case of mesenteric vein thrombosis (MVT) caused by testosterone-induced secondary polycythaemia. The findings from this case elucidate the importance to review medications as it may have a direct impact on the patient’s diagnosis. It is important to recognise that secondary polycythaemia is a known side effect of testosterone, thus, when someone taking testosterone presents with abdominal pain and an elevated haemoglobin and haematocrit, thrombosis must be on one's differential diagnosis.

Case presentation

A 59-year-old man presented to the emergency department with progressively worsening left lower quadrant abdominal pain for 2 weeks. He denied any alleviating factors and eating exacerbated the pain. He admits to constipation. His medical history is notable for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), GOLD stage III with a normal diffusion capacity, managed with ventolin, advair and spiriva and low testosterone for which he takes AndroGel. He denies any current tobacco or recreational drug use but admits to 1–2 beers a day. He does admit to smoking heavily in the past but quit 5 years ago.

On physical examination, the patient was tachycardic at a rate of 106 bpm and his oxygen saturation was 92% on 2 L nasal cannula. Abdominal examination revealed a distended abdomen that was soft and tender to palpation diffusely with absent bowel sounds. No rebound or guarding was noted.

Laboratory findings revealed elevated haemoglobin and haematocrit, 19.7 g/dL and 62.2%, respectively and a transaminitis with aspartate aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase, 70 and 78 U/L, respectively. CT of the abdomen confirmed findings consistent with early small bowel obstruction with inflammation and a questionable thrombosis of the superior mesenteric vein (figure 1). A CT angiogram of the abdomen and pelvis with and without contrast revealed oedema around the superior mesenteric vein suspicious for underlying superior mesenteric vein thrombosis (figure 2). Haematology was consulted and a diagnosis of primary polycythaemia vera was ruled out by negative Janus kinase 2 mutation.

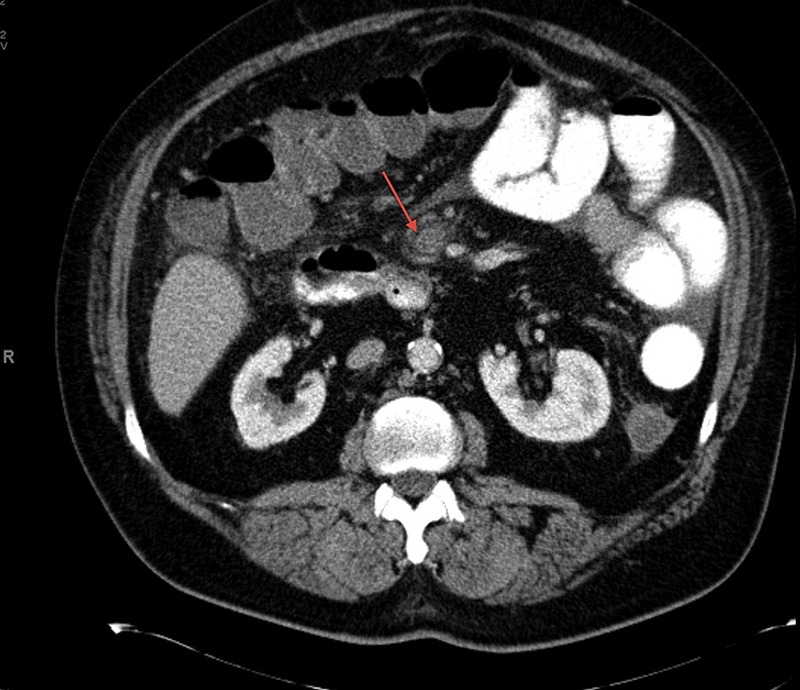

Figure 1.

CT of the abdomen with thrombosis of the superior mesenteric vein.

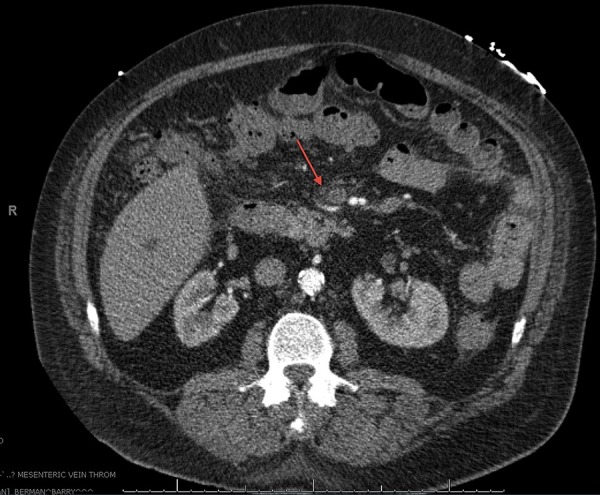

Figure 2.

CT angiogram of the abdomen and pelvis with and without contrast showing oedema around the superior mesenteric vein consistent with superior mesenteric vein thrombosis.

Treatment

The patient was started on full dose lovenox and subsequently discharged on rivaroxiban, and his COPD maintenance medications. AndroGel was discontinued.

Outcome and follow-up

Outpatient follow-up with haematology revealed a decrease in haemoglobin/haematocrit from 19.7 g/dL/62.2% to 17.8 g/dL/56.7% after discontinuation of AndroGel 2 months prior. The patient is currently continuing treatment with rivaroxiban for a total of 6 months.

Discussion

MVT often presenting as abdominal pain; however, it may present more acutely with distension, shock and peritoneal irritation indicating mesenteric infarct.1–3 It has been estimated to account for 0.002–0.06% of all inpatient admissions.2 The prevalence of MVT has increased with the use of CT which has an accuracy of approximately 90% for identifying MVT.1 2

MVT is seen in patients with a mean age of 45–60 years old. There is a slight male predominance. It is more commonly seen within the superior mesenteric vein, which drains the entire bowel from the second portion of the duodenum to approximately the right two-thirds of the transverse colon compared to the inferior mesenteric vein, which drains the left colon and enters into the splenic vein.1 2

MVT is usually caused by prothrombotic states that are either inherited or acquired.2 Table 1 lists the inherited and acquired causes of thrombophilias and hypercoaguable states.

Table 1.

Inherited and acquired causes of thrombophilias and hypercoaguable states

| Heritable thrombophilias | Antithrombin III deficiency Factor V Leiden mutation (activated protein C resistance phenotype) hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia Hyperfibrinogenemia JAK2 V16F mutation without overt MPD Plasminogen deficiency protein C deficiency Protein S deficiency Prothrombin 20210 mutation (PTHR A20210) Sickle cell disease |

| Acquired thrombophilias and systemic hypercoagulable states | Antiphospholipid antibodies Anticardiolipin antibodies β-2 Glycoprotein-1 antibodies Decompression sickness DIC Essential thrombocythemia Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia Hyperhomocysteinemia Malignancy Monoclonal gammopathy MPD Nephrotic syndrome Oral contraceptive agents and other medications Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria Polycythaemia vera Pregnancy |

| Intra-abdominal causes | Cirrhosis Congenital venous anomaly Inflammatory bowel disease Intestinal volvulus Intra-abdominal infection Pancreatitis Postoperative state Trauma |

| Idiopathic |

DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; MPD, myeloproliferative disorders.

As seen in table 2, a large number of medications have been implicated to cause prothrombotic states. The most commonly used include COX-2 inhibitors, hormonal therapies, chemotherapy agents and erythropoietin.2 4

Table 2.

Medications that have been implicated to cause prothrombotic states

| Cox-2 inhibitors | Celecoxib, rofecoxib and valdecoxib |

| Hormonal therapies | Oral contraceptives, hormonal replacement therapy and tamoxifen |

| Chemotherapy agents | Cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil |

| Exogenous performing enhancing drugs | Erythropoietin, testosterone |

Testosterone used to treat male hypogonadism, augments the action of erythropoietin.5–8 Erythropoietin is essential for erythropoiesis, the process by which erythrocytes are produced. Thus, stimulation of erythropoiesis leads to higher red blood cell counts and haemoglobin concentrations. Testosterone leads to an increase in haemoglobin by as much as 5–7% and can lead to polycythaemia in over 20% of men.5 Long-term administration of 1% AndroGel for 36 months showed that haemoglobin and haematocrit increased steadily until month 12.6 Although testosterone gels, such as AndroGel, pose a lower risk of polycythaemia than injectable modalities polycythaemia is still a known adverse side effect and may lead to increased incidence of vascular events.5 6 8 9 Monitoring patients with complete blood counts is essential and if the haematocrit rises above 54% testosterone therapy should be held until the haematocrit normalises.5

Erythropoietin is also stimulated by hypoxia as seen in patients with COPD. When oxygen depleted blood travels through the kidney, erythropoietin is stimulated increasing the amount of erythropoiesis thus increasing the amount of red blood cells.9–11 Recent studies suggest that secondary polycythaemia is less of an issue in modern COPD populations. Cote et al9 analysed the prevalence of secondary polycythaemia in 683 COPD outpatients and revealed a prevalence of only 6%.

Hypercoaguable states that lead to MVT are usually treated with discontinuation of potential offending agents, anticoagulation or thrombectomy.1 2 According to Harnik, most authorities recommend anticoagulation for 3–6 months in patients with acute MVT and a temporary risk factor and lifelong anticoagulation therapy for idiopathic thrombosis or have a persistent hypercoaguable state. In centres where there is expertise with thrombolysis and thrombectomy, aggressive intravascular therapy should be considered as an adjunct to anticoagulation.2 In our case, AndroGel was discontinued and medications to control the patient's COPD was provided to prevent secondary polycythaemia and a prothrombotic state. The patient was anticoagulated with rivaroxiban for a total of 6 months.

A literature review performed using PubMed confirmed the rarity of thromboembolic events caused by secondary polycythaemia induced by testosterone and hypoxia from COPD. This is the first case described in literature of MVT caused by secondary polycythaemia from AndroGel in the setting of COPD.

Learning points.

Mesenteric vein thrombosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients who present with abdominal pain and have laboratory data consistent with polycythaemia.

Testosterone supplementation augments the action of erythropoietin stimulating erythropoiesis, which leads to higher red blood cell counts and haemoglobin concentrations.

It is important to recognise that commonly prescribed medications and chronic diseases may cause secondary polycythaemia and thus a hypercoaguable state that can lead to thrombosis.

Acknowledgments

The North Broward Hospital District.

Footnotes

Contributors: HK and EP participated in the preparation of the manuscript and in the evaluation and editing of the manuscript. NB participated in the evaluation and editing of the manuscript. BB participated in the management of the patient from the specialty of Haematology/Oncology and the evaluation and editing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Singal AK, Kamath PS, Tefferi A. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. Vasc Med 2013;88:285–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harnik IG, Brandt LJ. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. Vasc Med 2010;15:407–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyon C, Clark DC. Diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in older patients. Am Fam Physician 2006;74:1537–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mintzer DM, Billet SN, Chmielewski L. Drug-induced hematologic syndromes. Adv Hematol 2009;2009:495863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osterberg EC, Bernie AM, Ramasamy R. Risks of testosterone replacement therapy in men. Indian J Urol 2014;30:2–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakshman KM, Basaria S. Safety and efficacy of testosterone gel in the treatment of male hypogonadism. Clin Interv Aging 2009;4:397–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siddique H, Smith JC, Corrall RJ. Reversal of polycythaemia induced by intramuscular androgen replacement using transdermal testosterone therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;60:143–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coviello AD, Kaplan B, Lakshman KM, et al. Effects of graded doses of testosterone on erythropoiesis in healthy young and older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:914–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent BD, Mitchell PD, McNicholas WT. Hypoxemia in patients with COPD: cause, effects, and disease progression. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2011;6:199–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patakas DA, Christaki PI, Louridas GE, et al. Control of breathing in patients with chronic obstructive lung diseases and secondary polycythemia after venesection. Respiration 1986;49:257–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadeem O, Gui J, Ornstein DL. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with secondary polycythemia. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2013;19:363–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]