Abstract

A Phase III community-based HIV vaccine trial using the ALVAC-HIV and AIDSVAX B/E prime-boost regimen (RV144) showed a modest vaccine efficacy of 31.2% against HIV acquisition. Participant's understanding of the trial is a key element of its success. This study aimed to understand participant's expectation and response to the overall results of the trial as well after unblinding. Using an open-ended questionnaire, data were collected from 400 participants who came for the unblinding visit. Fifty-three percent received the vaccine and 47% were placebo recipients. The median age was 30 years (range: 22–37). The observed vaccine efficacy of 31.2% was lower than expected by 67.75% of participants compared to higher than expected (by 6%), as expected (by 11.25%), and those with no expectation (15%). A majority of participants (71.5%) were happy and proud, and indicated that it was a good result. The rest were sad or disappointed (22.75%) or acquiescent (5.75%). After unblinding, 67.92% of the vaccine recipients had a positive response and 32.08% were acquiescent. Among placebo recipients, 85.11% were acquiescent and 10.11% indicated that being assigned to the vaccine group would have been better even though vaccine efficacy was only 31.2%. Despite the modest vaccine efficacy, a majority of study participants acknowledged the value of the trial and hoped that information from RV144 could be used for future vaccine development.

Introduction

Disclosure of results to clinical trial participants is a means of recognizing patients' rights and human dignity and has become an ethical obligation.1 Previous studies have shown that patients are interested in the results of clinical trials in which they have participated.2,3 A respectful, caring, and collaborative relationship between trial staff and volunteers is an important social contribution, and has been associated with volunteers' feeling of having a role in the research as “collaborators” and “pioneers” and not as mere research “subjects.”4,5

A community-based efficacy Phase III trial (RV144) of the prime-boost regimen using ALVAC-HIV (vCP1521) (Sanofi Pasteur) and AIDSVAX B/E (Global Solutions for Infectious Diseases) was conducted from October 2003 to June 2009 in Rayong and Chonburi provinces, Thailand.6 The aim of the study was to evaluate the vaccine efficacy by assessing two coprimary endpoints: prevention of HIV-1 acquisition and impact of vaccination on early HIV RNA load after infection. A total of 16,402 healthy HIV-uninfected Thai men and women participants between 18 and 30 years of age were enrolled regardless of their HIV risk (community risk). RV144 provided the first evidence that HIV vaccine protection against HIV acquisition could be achieved with an estimated vaccine efficacy of 31.2% at 42 months postenrollment.7

An initial in-depth discussion with structured interview to determine expectations of participants prior to the announcement of the vaccine efficacy result on September 24, 2009 was conducted in 64 RV144 volunteers from eight clinical sites (eight subjects from each site) from December 2008 to January 2009. Most participants (47/64, 73.4%) expected the vaccine to be efficacious and almost 40% (25/63) to be 100% efficacious.8 Such high expectations from participants needed clarification with regard to the meaning of the vaccine efficacy result and to their feelings after unblinding, elements important for researchers to understand.

The objectives of the present study were to describe and understand the participants' expectation and their feelings with regard to the vaccine efficacy result after unblinding.

Materials and Methods

This study involved 400 participants (convenience sample from 8 clinical sites with 50 participants per site) who came for their unblinding visit from October 12–22, 2009. Unblinding refers to a process whereby participants were individually informed whether they received the vaccine or the placebo. The final trial results were explained at this time as well. After obtaining verbal consent, study participants were interviewed using open and close-ended questionnaires (Box 1) to determine their expectations and “response” regarding the vaccine efficacy result. Then, once the unblinding had been performed, the participants were again interviewed regarding their opinion about the trial and their participation, and about being a vaccine or a placebo recipient.

Box 1.

Interview Questionnaire

| Interview questionnaire |

| Date of interview__________ |

| Respondent code__________ |

| Demographic characteristics |

| 1. Gender of respondent Male_____ Female_____ |

| 2. Highest level of education |

| a. Primary education d. Diploma |

| b. Lower secondary education e. Bachelor |

| c. Upper secondary education f. Master and above |

| 3. What do you do in your job?_________________ |

| Response on trial results |

| 1. Describe your feelings as you deal with trial results. |

| ______________________________________________ |

| ______________________________________________ |

| Please explain why___________________________ |

| Expectation on trial results |

| 1. Can you predict the outcome of the efficacy result? Yes ____No ____ |

| 2. On a scale of 0% to 100%, could you tell me what result you are expecting?____________ |

“Expectation” referred to the predicted outcome of the vaccine efficacy result before unblinding. Participants used a scale of 0% to 100% to rate their expected vaccine efficacy result. The level of expectation was categorized as higher than expected (expecting efficacy <31.2%), lower than expected (expecting efficacy >31.2%), as expected (expecting efficacy of 31.2%), and with no prior expectation. “Response” described the participant's feelings regarding the trial result or their randomization as vaccine or placebo recipient after unblinding. A positive response referred to being satisfied and proud of a good result, while disappointment and sadness represented a negative response. Acquiescence or a neutral response was indicated by acceptance of the result, no disappointment, or an indifferent comment. Study staff collected the information in a private area of the clinic to maintain the confidentiality of the participants.

Data management and analysis

Questionnaire responses were entered by the Vaccine Trial Center staff in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 15 for analysis. Data were mostly descriptive. Relationships between level of expectation and demographic variables were analyzed using Pearson's Chi-square test. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study participants

Of 400 participants interviewed, 212 (53%) received the vaccine and 188 (47%) were placebo recipients. Demographic characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. More than half of the participants were male (55.5%). The median age was 30 years (range: 22–37).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population

| Characteristic | N=400 n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |

| <26 | 37 (9.25) |

| 26–30 | 196 (49) |

| >30 | 167 (41.75) |

| Median age (range) | 30 (22–37) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 222 (55.50) |

| Female | 178 (44.50) |

| Education | |

| Primary and below | 117 (29.25) |

| Lower secondary education | 126 (31.50) |

| Upper secondary education | 100 (25) |

| Diploma/Bachelor | 57 (14.25) |

| Occupation | |

| Laborer | 60 (15) |

| Housewife | 32 (8) |

| Agricultural worker | 30 (7.50) |

| Employee | 191 (47.75) |

| Merchant/personal business owner | 62 (15.50) |

| Student/scholar | 7 (1.75) |

| Health professional | 7 (1.75) |

| Unemployed | 11 (2.75) |

Expectation of participants for vaccine efficacy

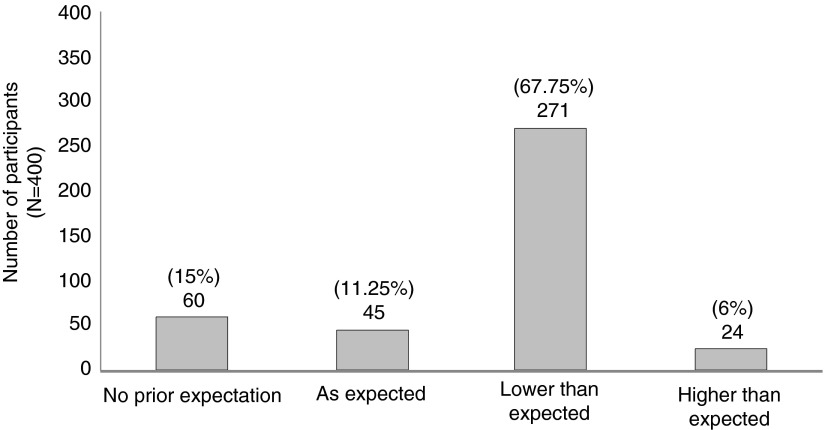

A majority of participants (271/400, 67.7%) indicated that vaccine efficacy was lower than expected while only 6% (24/400) considered the value higher than expected (Fig. 1). Highly educated participants were significantly less likely to expect vaccine efficacy (p=0.020). Comparatively, participants with upper secondary education were significantly more likely to indicate an expected value (p=0.009). Those with lower secondary education had more expectations than those with upper secondary education (p=0.011). There was no association between expectation and age, gender, treatment assignment, and occupation.

FIG. 1.

Expectation of participants for RV144 vaccine efficacy before their unbinding.

Response of participants on vaccine efficacy

Table 2 shows that after unblinding 71.5% of the participants (286/400) had a positive response while 22.7% and 5.7% had a negative or acquiescence/neutral response, respectively. There was no difference in response between gender (p=0.485, data not shown).

Table 2.

Response of Participants on Vaccine Efficacy of 31.2%

| Response | N=400 n (%) |

|---|---|

| Positive response | 286 (71.50) |

| Good | 184 (46) |

| Happy/proud | 102 (25.5) |

| Negative response | 91 (22.75) |

| Disappointed | 62 (15.5) |

| Sad | 29 (7.25) |

| Acquiescence or neutral response | 23 (5.75) |

Opinion of participants about the clinical trial

Only 32.2% (129/400) of the participants expressed their opinions about the clinical trial. More than half of them (89/129, 69%) believed that information from the study would accelerate future development or improvement of HIV vaccines. Only 17.2% (69/400) shared their opinion about themselves as trial participants. Of these, 42% (29/69) acknowledged the benefit of enhanced HIV/AIDS knowledge and social relationship, and were proud to be part of the trial. Similarly, 40.6% of participants hoped for the trial's success and use of the vaccine in Thailand (Table 3).

Table 3.

Opinion of Study Participants About the Clinical Trial and Their Participation

| Opinion | N=400 n (%) |

|---|---|

| Participant's opinion about the trial | 129a (32.2) |

| The information from this study could accelerate future development or improvement of HIV vaccines. | 89 (69.0) |

| HIV vaccine trial conducted in Thailand had shown some effectiveness. | 24 (18.6) |

| Clinical trial was successful and participants hoped that an HIV vaccine would be available in the future. | 16 (12.4) |

| Opinion about their trial participation | 69a (17.2) |

| They had some benefit, e.g., enhanced HIV/AIDS knowledge and social relationship and were proud to be part of the study. | 29 (42.0) |

| They hoped that the HIV vaccine trial will succeed and implement the the use of a vaccine in Thailand. | 28 (40.6) |

| They have to protect themselves against HIV infection. | 12 (17.4) |

Number of participants who provided feedback out of the 400 participants.

Response of participants after unblinding

Of the vaccine recipients, 67.9% had a positive response and 32.1% were acquiescent. However, 85.1% of placebo recipients were acquiescent while 10.1% indicated that being assigned to the vaccine group would have been better even though vaccine efficacy was only 31.2%.

Discussion

RV144 was the first clinical HIV vaccine efficacy trial to show a moderate vaccine efficacy (31.2%) against HIV acquisition, though not sufficient for licensure in Thailand.9 Our study showed that a majority of participants perceived positively the value of their participation in the trial despite the modest vaccine efficacy observed. This finding was similar to another study conducted in relation to the STEP trial, a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase IIb test-of-concept clinical trial conducted on 3,000 participants at high risk for HIV infection in the United States. Participants considered trial involvement as helping the community along with having a valuable personal experience.4 In our study, only 32% of the participants expressed an opinion. This might be explained by the fact that some Thai participants have difficulty in expressing their opinion as shown in a study among HIV-positive individuals.10 Our study also showed that highly educated participants were significantly less likely to expect the observed vaccine efficacy. This suggests a higher level of awareness on HIV infection and HIV vaccines and related challenges compared to participants who had a lower degree of education.

By participating in the trial, Thai volunteers were motivated by altruism. Forty-two percent of participants recognized some benefit such as enhanced knowledge of HIV/AIDS and prevention. This corroborates similar findings in a study involving 164 Thai participants from two previous Phase I/II HIV vaccine studies.5 All participants expressed the benefits of social contribution, knowledge, and feelings of having gained spiritual merit.5 Similarly, British participants in another study expressed the benefit of having contributed to the public good, regardless of any benefit to them.11 Conversely, in other studies, participants indicated that whatever their level of knowledge was, they would struggle to make sense of their participation in trials that randomize their allocation to vaccine or placebo.12 Clear and accurate patient information is important in clinical trials.13 The STEP study was terminated early following evidence of a higher rate of HIV infection in a subset of vaccine recipients with preexisting adenovirus type 5 antibodies.14

After unblinding, a participant expressed fear of actually receiving the test vaccine, although he was a placebo recipient. Another participant who received the vaccine expressed difficulty in understanding the complex results during the unblinding process, while another attributed his discontent to inadequate communication between participants and investigators throughout the study termination process rather than to the results. In contrast, in our study a majority of our study participants expressed positive feelings during unblinding despite a result that was less than expected. During the unblinding process, continuous discussion with study participants happened to be extremely valuable in facilitating the full understanding of the trial results.

Another study in Cambodia showed the local stakeholders' reported feelings of lack of power and a perceived absence of a forum for dialogue with investigators suggesting gaps in community engagement.15 It has been suggested that there should be an increase in focus and resource allocation to support posttrial information dissemination to multiple stakeholders such as specific populations at higher risk for HIV infection, trial volunteers, local communities and the general public, and civil society representatives including the media.4 Providing resources and/or appropriate local referrals for posttrial debriefing and psychosocial support would also help some vulnerable participants. Trial secondary or exploratory endpoints can be structured to include psychosocial measures, in addition to risk behavior assessment, including participant's evaluation of the process of clinical trials.

Qualitative research methods such as focus groups and key informant interviews, and knowledge of local culture as well as social marketing strategies, may help trial investigators to develop best practices in the engagement with local communities.16 Systematic implementation of integrated (qualitative and quantitative) social science research among populations at high risk for HIV, particularly in the context of HIV vaccine clinical trials, is important to attain the highest standards of trial implementation and community engagement.17 In addition, communicating vaccine trial results to the public should be in a clear and understandable manner.7 Furthermore, public education along with social marketing campaigns are important to increase public acceptance of partially efficacious HIV vaccines to achieve high levels of coverage, particularly among high-risk populations.18

Conclusions

Despite the RV144 modest efficacy of 31.2% against HIV acquisition, which did not meet participant's expectation, the majority of participants expressed their satisfaction and acknowledgment concerning the conduct and value of the trial. Knowledge of the expectations of trial participants should be an integral part of a clinical trial design as it may help researchers address each participant's need for an appropriate explanation of the objectives of future HIV vaccine efficacy trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all study participants and staff at study sites (health centers under the supervision of the Ministry of Public Health, Thailand), to the investigators from the Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, Vaccine Trial Center and the Center of Excellence for Biomedical and Public Health Informatics from Mahidol University, the U.S. Military HIV Research Program, and the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences for their participation and cooperation.

This work was supported by a cooperative agreement (W81XWH-11-2-0174) between the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc. and the U.S. Department of Defense. This research was funded in part by the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, U.S. National Institutes of Health.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the official views of funding institutions or organizations involved in the study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Eck SA, Sakoyan J, Desclaux A, et al. : “They should take time”: Disclosure of clinical trial results as part of a social relationship. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:873–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Partridge AH, Wong JS, Knudsen K, et al. : Offering participants results of a clinical trial: Sharing results of a negative study. Lancet 2005;365:963–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shalowitz DI. and Miller FG: Communicating the results of clinical research to participants: Attitudes, practices and future directions. PLoS Med 2008;5:714–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman PA, Yim S, Daley A, et al. : “Once bitten, twice shy”: Participant perspectives in the aftermath of an early HIV vaccine trial termination. Vaccine 2011;29:451–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maek-A-Nantawat W, Pitisuttithum P, Phonrat B, et al. : Evaluation of attitude, risk behavior and expectations among Thai participants in phase I/II HIV/AIDS vaccine trials. J Med Assoc Thai 2003;86:299–307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, et al. : Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. New Engl J Med 2009;361:2209–2220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization: Recommendations arising from the expert consultation on the future utility of the RV 144 vaccine regimen. March16–18, 2010, Bangkok, Thailand. Available at www.who.int/immunization/sage/HIV_3_Ethical_H_Rees_SAGE_April_2010.pdf. Accessed July6, 2012

- 8.Pitisuttithum P, Indrasuta C, Khowsroy K, et al. : Expectation of participants towards vaccine's efficacy in the phase III vaccine trial in Thailand. The 9th International Congress on AIDS and the Pacific (ICAAP), Bali, Indonesia, 2009. [Abstract WEPB 026]. Available at www.icaap9.org/userfiles/program%20book-11-8-09.pdf. Accessed September17, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robb ML, Rerks-Ngarm S, Nitayaphan S, et al. : Risk behavior and time as covariates for efficacy of the HIV vaccine regimen ALVAC (vCP1521) and AIDSVAX B/E: A post-hoc analysis of the Thai phase 3 efficacy trial RV144. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:531–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SJ, Li L, Iamsirithaworn S, and Khumton S: Disclosure challenges among people living with HIV in Thailand. IJNP 2013;19:374–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon-Woods M. and Tarrant C: Why do people cooperate with medical research? Findings from three studies. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:2215–2222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Featherstone K. and Donovan JL: “Why don't they just tell me straight, why allocate it?” The struggle to make sense of participating in a randomised controlled trial. Soc Sci Med 2002;55:709–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Featherstone K. and Donovan JL: Random allocation or allocation at random? Patients' perspectives of participation in a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 1998;317:1177–1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchbinder S, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, et al. : Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet 2008;372:1881–1893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page-Shafer K, Saphonn V, Sun LP, et al. : HIV prevention research in a resource-limited setting: The experience of planning a trial in Cambodia. Lancet 2005;366:1499–1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman PA: Towards a science of community engagement. [Correspondence]. Lancet 2006;367:302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindegger G, Milford C, Slack C, et al. : Beyond the checklist: Assessing understanding for HIV vaccine trial participation in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;43:560–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman PA. and Logie C: HIV vaccine acceptability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2010;24:1749–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]