Abstract

Intravaginal practices (IVP) are common among African women and are associated with HIV acquisition. A behavioral intervention to reduce IVP is a potential new HIV risk-reduction strategy. Fifty-eight HIV-1-uninfected Kenyan women reporting IVP and 42 women who denied IVP were followed for 3 months. Women using IVP attended a skill-building, theory-based group intervention occurring weekly for 3 weeks to encourage IVP cessation. Vaginal swabs at each visit were used to detect yeast, to detect bacterial vaginosis, and to characterize the vaginal microbiota. Intravaginal insertion of soapy water (59%) and lemon juice (45%) was most common among 58 IVP women. The group-counseling intervention led to a decrease in IVP from 95% (54/58) at baseline to 0% (0/39) at month 3 (p=0.001). After 3 months of cessation, there was a reduction in yeast on vaginal wet preparation (22% to 7%, p=0.011). Women in the IVP group were more likely to have a Lactobacillus iners-dominated vaginal microbiota at baseline compared to controls [odds ratio (OR), 6.4, p=0.006] without significant change in the microbiota after IVP cessation. The group counseling intervention was effective in reducing IVP for 3 months. Reducing IVP may be important in itself, as well as to support effective use of vaginal microbicides, to prevent HIV acquisition.

Introduction

Maintaining a healthy vaginal mucosa and microbiota is key to reducing adverse consequences such as pelvic inflammatory disease and HIV-1 infection.1 Dysbiosis (i.e., imbalance) of the vaginal microbiota, bacterial vaginosis (BV), and vaginal candidiasis are associated with increased HIV-1 risk.2,3

Natural dynamics of the vaginal microbiota lead to temporary disruptions; however, certain sexual behaviors, contraceptive methods, and intravaginal practices (IVP) can also lead to vaginal microbiota imbalance. Intravaginal practices are common throughout sub-Saharan Africa,4 especially among high-risk women such as female sex workers (FSW).5 As outlined by the World Health Organization,4 these include internal insertion of fingers and other substances including fluids (douching) into the vagina.6 These practices are associated with a decreased abundance and proportion of Lactobacillus sp., increased BV, and higher risk for HIV-1.7,8 In longitudinal follow-up of Kenyan FSWs, IVP increased HIV-1 risk ∼4-fold.9 The important implication of these findings is that eliminating these practices may reduce BV and HIV acquisition.

Intravaginal practices are deeply ingrained in cultural norms and beliefs. Nonetheless, a U.S. trial demonstrated that women receiving individualized counseling were more likely to stop their IVP (OR 1.60 at 12 months).10 A recent study among Kenyan FSW found that a theory-based behavioral intervention had a positive effect in reducing IVP over 1 month.11 However, similar studies have not been conducted in Africa among non-FSWs. The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate an information, motivation, and behavioral skills (IMB) theory-based behavioral intervention to encourage cessation of IVP for 3 months in HIV-uninfected non-FSW Kenyan women. Our study also set out to include the potential impact of an IVP intervention on the composition of the vaginal microbiota, epithelium integrity, vaginal inflammatory cytokines, and activated immune cells as key biomarkers of vaginal ecology relevant to HIV-1 acquisition risk.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Recruitment

The study was conducted at Bomu Medical Centre in Mombasa, Kenya. Participants were recruited from the general medical clinic via flyers and staff information about the study. Community recruitment occurred via a study outreach staff person who was familiar with the population; potential interested individuals were sent to the clinic for assessment of eligibility. Participants were provided information about the study by trained study staff and consented. From September 2010 to July 2011, we recruited women 18 to 45 years old. Subjects were required to be asymptomatic, sexually active (at least one episode of sex in the last year), and not self-identifying as a FSW. Exclusion criteria included HIV or other infections in the past 3 months, pregnancy or being postpartum in the past 3 months, and the use of hormonal contraception in the past 2 months, as these can influence the composition of the vaginal microbiota.

Ethics

Participants signed informed consent following procedures and instruments approved by institutional review boards at New York University School of Medicine and at Kenyatta National Hospital in Kenya.

Participants who reported regular IVP (“washing or inserting substances into your vagina”) were assigned to the IVP group. To compare biological outcomes between women in the intervention group versus women who did not perform IVP, we enrolled women who reported never engaging in IVP to serve as controls.

Study procedures

At baseline, women were interviewed using a standardized questionnaire. If control women reported IVP they were excluded from the study. During baseline, IVP women were asked to cease IVP for 3 months and received the intervention once a week for three consecutive weeks. Women were asked to describe substances that they used and to indicate specific washing techniques (use of fingers or cloth in introitus on a pelvic model; depth was noted by staff on study forms). Information regarding intrapersonal and interpersonal motivations for IVP were noted in the study questionnaire. All study participants were asked to return for follow-up 1- and 3-month visits.

Background, theoretical framework, description, and rationale for the intervention

A brief intervention approach was selected since the literature has shown that some brief interventions delivered in clinical settings can be effective12 given that both patient and provider time have multiple competing demands. The behavioral framework used for the intervention included IMB skills13 and transtheoretical stage of change models.14 Evidence for applicability of IMB to health conditions including and beyond HIV disease is accruing.15 The Transtheoretical Model allowed us to classify women as being at the stage of precontemplation (not ready for change to reduce or stop IVP), contemplation (ready to consider making a change soon), preparation (ready to take action toward behavior change), action (initiating behavior change), or maintenance (sustaining behavior change over time).14 These behavioral theories were selected as being most salient to the overall goal of harm reduction, to provide information about risks, to understand motivations behind behaviors, and to support less harmful behaviors or substitutions, along a continuum of readiness to make changes.

All group sessions were delivered in Kiswahili in a small group format with two trained counselors (nurses) only to the IVP-using participants. The counselors were trained by experienced staff who had delivered the intervention previously to a female sex worker population in Mombasa.16 The counselors followed an intervention manual outlining elements for each session. The group sessions focused on readiness to modify vaginal washing, barriers, facilitators, attitudes, self-efficacy to modify intravaginal practices, as well as sex-partner-related, cultural, familial, and economic factors, and healthy substitution behaviors. Staff incorporated client-centered motivational-interviewing-based communication such as the use of open-ended questions, affirmations, reflection, and summaries.

Before each weekly intervention session, women completed a survey assessing readiness to stop IVP, engagement in and type of IVP in the past week, sexual activity in the past week, gender of sexual partner, and condom use. Intervention session one provided information about female anatomy, IVP risks, HIV/STD information, and benefits of a healthy vaginal environment. It was acknowledged that women engage in these practices for many reasons, and that changing behavior can be difficult. Session two covered motivations and reasons for IVP, allowing participants to discuss the influence of sexual/emotional relationships, cultural expectations, and health beliefs on intravaginal practices and HIV/STI risk. This session introduced Kegel exercises, e.g., as a substitute for IVP for the vaginal tightness goal that was perceived to be a preference of the women's sex partners and, thus, one of the reasons that many women engaged in IVP. Session three covered strategies for reducing and/or stopping harmful IVP and problem-solving among the group; this included role plays as well as women describing how they had tried to attain their goals including talking with their partners.

Pelvic specimen collection procedures

During pelvic examinations, specimens were collected and a rapid pregnancy test (QuickVu;Quidel Corporation, San Diego, CA) and a rapid HIV test (Determine HIV-1/2, Abbot Japan Co Ltd, Tokyo and UniGold HIV,Trinity Biotech PLC, Bray) were performed.

Colposcopy at all three visits assessed epithelial and vascular lesions as classified by the Contraceptive Research and Development Program and World Health Organization. Vaginal swabs were taken for wet mount, Nugent scoring,17 vaginal pH, Lactobacillus culture, and whiff test. Cervicovaginal lavage (CVL) specimens were collected, as well as endocervical samples for Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) testing at baseline.

Blood was collected for syphilis testing (rapid plasma reagin titer confirmed by Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay) and HSV-2 serology (HerpeSelect-2, Focus Diagnostics, Cypress, CA). All infections diagnosed were treated by Kenyan national guidelines.

Laboratory methods

Laboratory personnel were blinded to participants' IVP status. A detailed description of laboratory specimen handling and analysis is included in the Appendix (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid). We defined abnormal vaginal microbiota (including intermediate and BV) as a Gram-stain Nugent score of 4–10.

Trichomonas vaginalis-positive samples were defined by the presence of motile trichomonads, and vaginal candidiasis by the presence of budding yeast or hyphae on vaginal wet mount examination. Lactobacillus presence was defined using colonial morphologic characteristics and Gram stain findings and classified as H2O2 producers if blue pigment was detectable.

Cervical cytokine and chemokine measurements

Levels (pg/ml) of six cytokines were measured using the Cytokine Bead Array kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA).18

Cervical cytobrush immunophenotyping

Samples were processed using a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Flow cytometry data were analyzed in FlowJo v.9.2 (Tree Star, Inc., Stanford University).

Vaginal microbiota studies

Genomic DNA was extracted from archived vaginal swabs. We used two universal primers, 27F and 534R, for PCR amplification of the V1–V3 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene.19 The purified amplicon mixtures were sequenced by 454 pyrosequencing with 454 Life Sciences primer A by the Genomics Resource Center at the Institute for Genome Sciences, University of Maryland School of Medicine. The QIIME software package20 was used for quality control of the sequence reads with the split-library.pl script. Taxonomic assignments were performed using a combination of pplacer21 and speciateIT (http://speciateIT.sourceforge.net).

Statistical analysis

We used a repeated-measures study design where intravaginal practice at baseline was the key between-subjects factor and time was the key within-subjects factor. We utilized data from our quantitative questionnaire to assess changes in IVP across the three study visits. To assess women's readiness to stop IVP, we assessed any movement in the five stages of change classification from baseline to month 3.

For comparisons of vaginal microbiota types, mucosal epithelial lesions, and inflammatory markers, we compared baseline to the 3-month visit. Lesions were categorized as epithelial disruption, vascular disruption, erythema, and friability, but since relatively few lesions were observed, we combined categories into one variable indicating any noniatrogenic lesions. We utilized generalized estimating equation (GEE) models with a logit link and exchangeable correlation structure to compare lesions and BV baseline and 3 months. GEE models with a Gaussian link and exchangeable correlation structure compared changes in cytokines between baseline and 3 months. The GEE analysis approach was selected as a single framework accommodating categorical and continuous outcome variables, confounding factors, and clustering of repeated observations within individual women. Potential confounding factors included in the models were sexual risk behaviors, genital tract infections, and reported vaginal symptoms. Cytokine data were log10 transformed. Analyses were performed using Stata (Version 12, StataCorp, College Station, TX, 2011).

Vaginal microbiota community clustering analyses

The dissimilarity between community states (i.e., vaginal species composition and abundance) was measured with the Jensen–Shannon metric.22 The clustering of community states into community state types (CSTs) was done with hierarchical clustering based on the Jensen–Shannon distances between all pairs of community states and Ward linkage.22

Results

Baseline characteristics

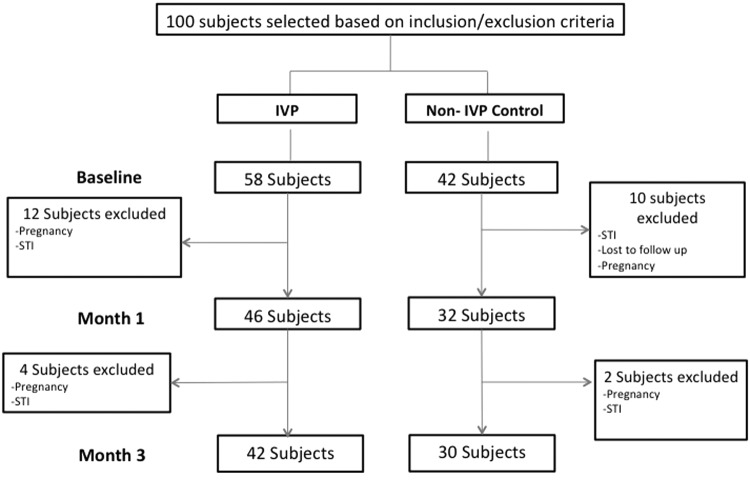

Between September 2010 and July 2011, 58 HIV-uninfected women were enrolled into the IVP group and 42 women into the control group. During the study, 16 IVP women and 12 control women were excluded (voluntary withdrawal n=12, pregnancy n=7, new symptoms n=8, or lost to follow-up n=1). Forty-two (72%) IVP group women and 30 (73%) control group women completed the study (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram of women enrolled and excluded during the study period. STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Table 1 describes participant baseline characteristics. Women in the IVP group were significantly more likely to have frequent sexual intercourse (p=0.008) but did not report a significantly higher number of sexual partners. We found no significant differences in vaginal inflammatory cytokines, percent cervical CD4+ T cells expressing HIV receptors CCR5 and integrin β7,23 prevalence of T. vaginalis, HSV-2, NG or CT, or BV as determined by Nugent score in women in IVP and control groups during baseline. When comparing both groups of women to the nationally representative Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey (KAIS) of 2012, our sample had a somewhat higher proportion of women who said they were married/cohabiting (KAIS 62.0%), though proportions who said that they were living with a partner or spouse were similar (KAIS 2012 78.0%). Age distributions were similar to national KAIS 2012 data, as was reported number of sex partners. The level of unemployment was higher in our sample than that noted as a national average among women in KAIS 2012 (62.1%).24

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| IVP group (n=58) | Non-IVP group (n=42) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 25.7 (19–44) | 27.8 (18–41) | 0.058a |

| Currently married with one spouse, N (%) | 43 (74) | 38 (90) | 0.069 |

| Unemployed, N (%) | 38 (66) | 32 (76) | 0.277 |

| Reporting a single sexual partner, N (%) | 55 (95) | 42 (100) | 0.260 |

| Sexual intercourse 2+/week, N (%) | 40 (70) | 18 (43) | 0.008 |

| Reporting history of STD symptoms, N (%) | 14 (24) | 7 (17) | 0.459 |

| Reporting past diagnosis of an STD, N (%) | 15 (26) | 9 (22) | 0.644 |

| Herpes simplex virus-2 positive, N (%) | 28 (48) | 18 (43) | 0.685 |

| Gonorrhea, N (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Chlamydia, N (%) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.508 |

| Trichomonas, N (%) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 0.637 |

Mann–Whitney test. All others are by Fisher's exact test.

IVP, intravaginal practice; STD, sexually transmitted diseases.

Women's use of IVP (motivations and use)

As summarized in Table 2, behavioral data indicated that many women learned IVP from peers and engage in these practices because they believe that their male partners prefer the sexual experience that intravaginal washing is thought to bring. At baseline 41% of the IVP women did not believe that these practices were harmful. Specific behaviors noted included use of caustic materials such as detergents and “shabu” (alum). These are likely more important to target in a harm reduction approach in which women can be encouraged to substitute less risky practices, until they feel they are able to cease IVP entirely. The substitution of Kegel's exercises is an example of this approach that was incorporated into the intervention.

Table 2.

Intravaginal Practices and Motivations Reported at Baseline Visit

| Characteristics | IVP group (n=58) |

|---|---|

| Median age at start of IVP, years (range) | 23 (15–38) |

| Learned IVP practices from, N (%) | |

| Friends | 48 (83) |

| Self-taught | 7 (12) |

| Relatives (grandmother, mother, sister) | 3 (5) |

| Reason for starting intravaginal practices, N (%) | |

| Male sexual experience or after childbirth (for vaginal dryness or tightening) | 25 (43) |

| Peer pressure (friends were doing it, told by relatives to do it) | 20 (34) |

| Hygiene (to remove foul smell or to feel clean) | 13 (22) |

| Reason for currently engaging in intravaginal practices, N (%)a | |

| Hygiene (to remove foul smell or to feel clean) | 37 (64) |

| Male sexual experience or after childbirth (for vaginal dryness or tightening) | 36 (62) |

| Female sexual experience | 3 (5) |

| Frequency of intravaginal practice | |

| Daily practice (n=33) median #/day (range) | 2 (1–5) |

| Weekly practice (n=23), median #/week (range) | 2 (1–9) |

| Monthly practice (n=1), median #/month | 2 |

| Method of insertion of substances into the vagina, N (%)a | |

| Finger | 35 (60) |

| Cloth | 28 (48) |

| Substances inserted into vagina, N (%)a | |

| Soap and water | 34 (59) |

| Lemon or lime juice | 26 (45) |

| Soda (Coca-Cola or Sprite) | 11 (19) |

| Salt or salt water | 10 (17) |

| Detergent | 9 (15) |

| Garlic | 7 (12) |

| Shabu (alum powder) | 4 (7) |

| Brewed tea | 4 (7) |

| Other (cream, herbs) | 4 (7) |

| Timing of intravaginal washing, N (%)a | |

| Before sexual intercourse | 25 (43) |

| After sexual intercourse | 19 (33) |

| Before and after sexual intercourse | 10 (17) |

| After menses | 9 (16) |

| What are the benefits of doing IVP? N (%)a | |

| Satisfy sexual partner | 19 (33) |

| Feel clean | 18 (31) |

| To keep the vagina dry and tight | 13 (22) |

| Feel like a virgin | 5 (9) |

| Prevents infection | 3 (5) |

| What are the harms of doing IVP? N (%) | |

| IVP is not harmful | 24 (41) |

| Painful sexual intercourse | 19 (33) |

| Causes vaginal itching, burning, or bruising | 13 (22) |

| What would it take to NOT do IVP at all? | |

| Believe harm outweighs good, N (%) | 50 (86) |

Women reported more than one reason for engaging in intravaginal practices (IVP); therefore the total percentage is greater than 100%.

The 3-week behavioral intervention for IVP cessation was effective

Table 2 describes IVP reported at baseline. The average age when starting these practices was 23 years (range 15–38); 54% reported personal hygiene and 46% reported vaginal tightness/dryness to enhance male sexual pleasure as the principal reason for engaging in IVP. Over half the women (57%) reported daily IVP at a median of twice daily (range, 1–5 times daily). The most common substances inserted into the vagina were soap and water (n=34, 59%), lemon juice (n=26, 45%), soda (n=11, 19%), and salt (n=10, 17%) (numbers add up to >100%). Intravaginal practices were conducted primarily before or after sexual intercourse (43% and 33%, respectively).

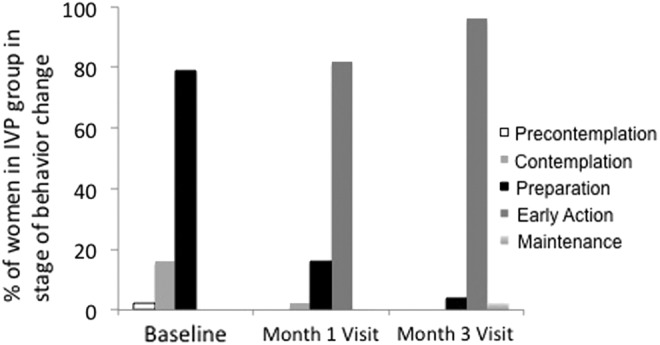

Between baseline when women were actively engaged in IVP and 3 months, there was a significant shift in the stage of behavioral change (Table 3 and Fig. 2). At baseline, most women were in the first three stages of behavior change (precontemplation 1.8%, contemplation 15.8%, and preparation 78.9%). Women increased one or more stages from baseline, typically increasing from “preparation” to “early action” stages (p<0.001) within a month. The proportion of women reporting IVP the previous week decreased from 94% (54/58) at baseline to 0% (0/39) after 3 months (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Interview Before Each Vaginal Examination for Intravaginal and Non-Intravaginal Groups

| IVP group | Non-IVP group | |

|---|---|---|

| Engaged in IVP 7 days before pelvic examination | ||

| Baseline | 54/58 (93%) | 0/41 (0%) |

| 1 month | 1/46 (2%) | 1/31 (3%) |

| 3 months | 0/36 (0%) | 0/29 (0%) |

| Median number of times engaging in IVP 7 days before pelvic examination (range) | ||

| Baseline | 4 (1–11)a | 0 |

| 1 month | 1 (1)b | 1 (1) |

| 3 months | 0 | 0 |

| Number of women reporting use of the following substances 7 days before baseline pelvic examination (n=54), N (%) | ||

| Water alone | 9 (54) | — |

| Lemon or lime juice | 26 (48) | — |

| Soap and water | 21 (39) | — |

| Detergent | 20 (37) | — |

| Soda (Coca-Cola or Sprite) | 13 (24) | — |

| Garlic | 7 (13) | — |

| Salt or salt water | 5 (9) | — |

| Brewed tea | 5 (9) | — |

| Shabu (alum powder) | 4 (7) | — |

| Other (lotion, herbs, lubricant) | 4 (7) | — |

| Sexual intercourse without a condom during the 7 days before pelvic examination? | ||

| Baseline | 33/58 (57%) | 29/42 (69%) |

| 1 month | 26/48 (54%) | 21/32 (66%) |

| 3 months | 25/39 (64%) | 19/30 (63%) |

n=54 participants in the IVP group.

n=1 participant in the IVP group and one in the non-IVP group.

IVP, intravaginal practice.

FIG. 2.

Proportion of women in the intravaginal practice (IVP) group in one of five stages of behavior change.

Vaginal epithelial lesions were rare

Colposcopy revealed that vaginal and cervical lesions were rare (2% of women in both groups without significant change between visits). Over the entire cohort and study periods, there were 47 reports of any type of vaginal or cervical abnormality (cervical epithelial disruption n=1, epithelial friability in vagina or cervix n=20, cervical erythema n=15, cervical vascular disruption n=2, vaginal erythema n=1). Women practicing IVP were not more likely to have epithelial lesions compared to women who did not.

The prevalence of HSV was high

Around half of the IVP women (28, 48%) and 43% (18) of the control women had positive HSV-2 serology (p=0.685). Two IVP women had C. trachomatis and none had N. gonorrhoeae.

Women with C. trachomatis or HSV-2 infection at baseline were more likely to have elevated cervicovaginal cytokines compared to women who were uninfected by both [tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α 3.21 pg/ml vs. 1.27 pg/ml, p=0.011; interleukin (IL)-6 52.29 pg/ml vs. 32.10 pg/ml, p=0.028; interferon (IFN)-γ 1.96 pg/ml vs. 1.03 pg/ml, p=0.057].

Prevalence of vaginal candidiasis significantly decreased after IVP cessation

The prevalence of vaginal candidiasis decreased in the IVP group from 22% to 7% (p=0.011) whereas a similar decrease was not seen in women in the control group (Table 4). The decrease in vaginal candidiasis remained significant after controlling for frequency of sexual activity the week before the pelvic examination. Women in the IVP group did not have a significantly higher prevalence of vaginal candidiasis at baseline compared to women who did not engage in IVP (22% vs. 12%; p=0.199).

Table 4.

Changes in Vaginal Environment Between Baseline and Month 1 and Month 3

| Baseline | Month 1 | Month 3 | Baseline vs. month 3, p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changes After Cessation of Intravaginal Practices | ||||

| Mean vaginal pH | 5.28 | 5.08 | 5.15 | 0.486 |

| BV by Nugent score, N (%) | 10/58 (17) | 4/46 (9) | 6/42 (14) | 0.770 |

| Positive Lactobacillus culture | 22/58 (38) | 20/46 (43) | 17/42 (40) | 0.863 |

| H2O2 producing Lactobacillus | 7/58 (12) | 5/46 (11) | 8/42 (19) | 0.228 |

| Vaginal candidiasis | 12/58 (22) | 8/46 (17) | 3/42 (7) | 0.011 |

| Cytokines [mean log10 transformed, pg/ml (SD)] | ||||

| IFN-γ | 1.43 [3.21] | 1.19 [1.62] | 0.60 [1.10] | 0.112 |

| TNF-α | 2.47 [6.10] | 0.87 [1.91] | 0.97 [4.02] | 0.006 |

| IL-10 | 0.62 [1.07] | 0.50 [0.98] | 0.58 [2.06] | 0.172 |

| IL-6 | 41.32 [62] | 24.81 [56] | 24.02 [68] | 0.001 |

| IL-4 | 0.04 [0.25] | 0.22 [0.73] | 0.15 [0.48] | 0.171 |

| IL-2 | 0.58 [0.72] | 0.76 [0.93] | 0.56 [0.69] | 0.913 |

| % CCR5+CD4+ T cells | 65.39 | 66.82 | 65.52 | 0.822 |

| % CCR5+ß7hi+CD4+ T cells | 12.92 | 11.22 | 10.50 | 0.240 |

| Changes Among Women Who Do Not Engage in Intravaginal Practices | ||||

| Mean vaginal pH | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 0.628 |

| BV by Nugent score, N (%) | 13/42 (31) | 6/32 (19) | 6/30 (20) | 0.280 |

| Positive Lactobacillus culture | 14/42 (33) | 9/32 (28) | 14/30 (47) | 0.166 |

| H2O2 producing Lactobacillus | 4/42 (10) | 5/32 (16) | 2/30 (7) | 0.308 |

| Vaginal candidiasis | 5/42 (12) | 7/32 (22) | 7/30 (23) | 0.197 |

| Cytokines [mean log10 transformed, pg/ml (SD)] | ||||

| IFN-γ | 1.96 [3.12] | 0.94 [1.57] | 1.15 [0.89] | 0.626 |

| TNF-α | 3.61 [8.82] | 0.97 [1.90] | 0.87 [1.59] | 0.005 |

| IL-10 | 0.85 [1.69] | 0.47 [1.04] | 0.68 [0.92] | 0.856 |

| IL-6 | 91.2 [182] | 21.21 [31] | 16 [19] | 0.041 |

| IL-4 | 0.38 [0.70] | 0.46 [1.68] | 0.27 [0.62] | 0.419 |

| IL-2 | 2.15 [3.57] | 0.81 [0.72] | 1.03 [1.04] | 0.092 |

| % CCR5+CD4+ T cells | 68 [13] | 67 [16] | 71 [14] | 0.114 |

| % CCR5+ß7hi+CD4+ T cells | 10.9 [9.7] | 12.5 [9.8] | 9.65 [4] | 0.254 |

p values from either a binomial generalized estimating equation (GEE) with logit link or a Gaussian GEE analysis.

Figures in bold are statistically significant.

BV, bacterial vaginosis; SD, standard deviation; IFN, interferon; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin.

Vaginal IL-6 and TNF-α levels decreased over 3 months

Women in the IVP and control groups had significant decreases in vaginal IL-6 (41 pg/ml to 24 pg/ml, p=0.001; 3.61 pg/ml to 0.87 pg/ml, p=0.005, respectively) and TNF-α levels (2.47 pg/ml to 0.97 pg/ml, p=0.006; 91.2 pg/ml to 16 pg/ml, p=0.04) (Table 4).

Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis did not change after IVP cessation

At baseline, 10 (17%) of 58 IVP women had BV by Nugent criteria compared to 13 (31%) of 42 control group women (p=0.149); proportions of BV did not significantly change statistically by month 3 (p=0.770 among IVP women and p=0.280 among controls, Table 4).

Women who engage in IVP are more likely to harbor a vaginal microbiota dominated by L. iners

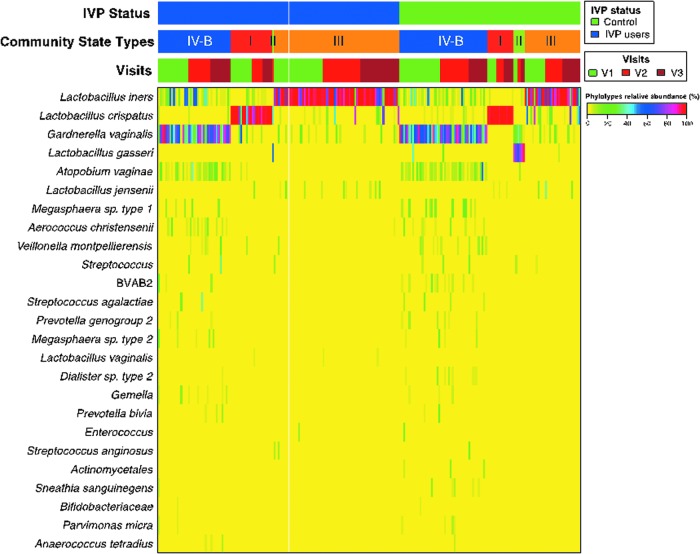

We characterized the vaginal microbiota of 97 women (55 IVP and 42 controls) using 454 pyrosequencing of barcoded 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions V1–V3. Of 250 vaginal-swab samples processed, 226 had sufficient reads (>1,000, median reads/sample 5,462) and were analyzed. There were 56 women with samples from all three visits, 17 with samples from two visits, and 24 with samples from the baseline visit. Samples were clustered into four CSTs, three of which were most often dominated by a Lactobacillus spp. [L. iners (CST III), L. crispatus (CST I), and L. gasseri (CST II)] and the fourth by Gardnerella vaginalis (CST IV-B).

Figure 3 represents a heatmap of percentage abundances of microbial taxa in the vaginal communities of subjects at baseline and at 1 and 3 months. Each community was clustered using hierarchical clustering according to Gajer et al.22 At baseline, there were significantly more women with CST III (mostly dominated by L. iners) in the IVP group than the control group [odds ratio (OR), 6.4, p=0.006] and significantly fewer CST IV-B (often dominated by G. vaginalis) in the IVP group (OR, 0.08, p=0.004). This remained significant after controlling for age, sexual activity (within the last 4 weeks vs. >4 weeks ago), and HSV status. There was no significant change in CST between baseline and 3-month visits in control group women.

FIG. 3.

Heatmap of percentage abundances of microbial taxa found in the vaginal communities of the subjects at baseline and at 3 and 6 months by intravaginal practice (IVP) status. Each community was clustered in community state types using hierarchical clustering.

Discussion

Intravaginal practices are common in many countries in Africa where HIV is prevalent. For example, a population-level survey in KwaZulu-Natal found that over half of women reported intravaginal cleaning.4 Recent systematic reviews that have been published of prospective longitudinal studies examining associations between IVP and HIV infection acquisition have revealed that using IVP did not protect from HIV and led to an increased risk of BV. Furthermore, IVP may directly impact HIV prevention efforts by potentially diminishing the efficacy of vaginal microbicides. For these reasons, interventions to discourage IVP may be important to reduce individual and population spread of HIV infection.

In this study, we demonstrate that a theory-based behavioral intervention to encourage cessation of IVP among HIV-uninfected general-population Kenyan women was effective at reducing the reported practice and that this effect was sustained over 3 months. This supports the results of a 1-month pilot study using the same behavioral intervention in HIV-uninfected Kenyan FSWs engaged in IVP.25 Other studies conducted in the United States have also reported some success.10

We found that cessation of IVP for 3 months did not reduce BV. Another pilot study in the United States on the impact of a 12-week douching cessation on BV also did not find a statistically significant decrease in BV occurrence.26

At baseline, we found that women who engaged in IVP were more likely to harbor a vaginal CST dominated by L. iners compared to women denying IVP, independent of frequency of sexual activity. L. iners has only recently been described because of fastidious culture requirements and is now recognized as one of the most common vaginal bacteria,19 especially during transition such as after metronidazole treatment.27 It is possible that regular IVP leads to rapid vaginal environment fluctuations that selects L. iners, which is adapted to survive under a range of conditions.28 We found no significant shift in the relative composition of the vaginal microbiota after IVP cessation, suggesting that 3 months after cessation of a major disturbance (IVP) may be too soon to see substantial shifts in the vaginal microbiota. Alternatively, IVP cessation may have been overreported resulting in little change in actual perturbation frequency and observed microbiota.

Our study incorporated biomarkers including CCR5 expression in order to assess the potential impact on the vaginal environment (including the microbiota) of IVPs and, thus, HIV risk. Several observations on changes in vaginal biomarkers therefore deserve mention. First, HSV-2-seropositive women were significantly more likely to have elevated vaginal proinflammatory cytokines compared to HSV-2-negative women. This is biologically plausible as HSV-2 is associated with an increased risk of HIV acquisition.29 Second, few longitudinal data exist on changes in cervical CD4 T cells in African women. We found that among women in both groups the proportion of cervical CD4+ expressing CCR5+ is high (66%) and stable over 3 months. Finally, we observed a decrease in vaginal IL-6 and TNF-α levels between baseline and 1- and 3-month visits in both IVP and control groups. The reason for this decrease is unclear.

Several caveats should be highlighted. The majority of women were in the preparatory phase of behavioral change likely reflecting selection bias, since women who may have been more resistant to IVP cessation may have declined to enroll. Future studies in Africa could randomize IVP women to the intervention, which would include women at all stages of behavioral change. This strategy was found to be feasible in a U.S. population.30 Limited follow-up time precludes the assessment of the durability of the behavior change observed. Finally, the loss to follow-up rate (27%) may have reduced the power to assess differences in vaginal milieu changes between women in the IVP and control groups. Women enrolled in our study were similar in some characteristics to national adult survey data.

In summary, we describe an effective 3-week group-counseling intervention to encourage cessation of intravaginal practices and found quantitative improvements in vaginal health, looking at both behavioral and biomarker outcomes. Implications for women's health includes the benefit of reduced reproductive tract disorders including candidiasis, as well as a potential reduced HIV risk. A potential, though not yet proven, benefit may include noninterference with microbicide activity by reducing IVP. Microbicides are an important female-controlled HIV prevention method. It has been noted that because intravaginal practices present a risk of diluting efficacy through removing or interfering with microbicides, more work is needed to understand motivations and risk reduction around IVP in the context of effective microbicide use.6 Conducting large-scale behavioral interventions on intravaginal cessation should be an important component to future microbicide trials conducted in areas in which intravaginal practices are prevalent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Grand Challenges Explorations grant [OPP1018122] to A.K.; National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health [1UL1RR029893] to S.S.; the Gilead Foundation grant to S.S.; and the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health [5U01AI070921 and 1UH2AI83264] to J.R.

We thank all the participants and staff from Bomu Medical Centre and Coast Provincial General Hospital involved in the study. We also thank the staff of the Ganjoni Clinic for participating in the study. We thank Professor Bart Kahr at NYU Chemistry for shabu specimen analysis and Nok Chhun for manuscript assistance

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Srinivasan S. and Fredricks DN: The human vaginal bacterial biota and bacterial vaginosis. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis 2008;2008:750479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Low N, Chersich MF, Schmidlin K, et al. : Intravaginal practices, bacterial vaginosis, and HIV infection in women: Individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2011;8(2):e1000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van de Wijgert JH, Morrison CS, Cornelisse PG, et al. : Bacterial vaginosis and vaginal yeast, but not vaginal cleansing, increase HIV-1 acquisition in African women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;48(2):203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hull T, Hilber AM, Chersich MF, et al. : Prevalence, motivations, and adverse effects of vaginal practices in Africa and Asia: Findings from a multicountry household survey. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20(7):1097–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Priddy FH, Wakasiaka S, Hoang TD, et al. : Anal sex, vaginal practices, and HIV incidence in female sex workers in urban Kenya: Implications for the development of intravaginal HIV prevention methods. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2011;27(10):1067–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gafos M, Pool R, Mzimela MA, et al. : The implications of post-coital intravaginal cleansing for the introduction of vaginal microbicides in South Africa. AIDS Behav 2014;18(2):297–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilber AM, Francis SC, Chersich M, et al. : Intravaginal practices, vaginal infections and HIV acquisition: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 5(2):e9119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Hassan WM, et al. : Improvement of vaginal health for Kenyan women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: Results of a randomized trial. J Infect Dis 2008;197(10):1361–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McClelland RS, Lavreys L, Hassan WM, et al. : Vaginal washing and increased risk of HIV-1 acquisition among African women: A 10-year prospective study. AIDS 2006;20(2):269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimley DM, Oh MK, Desmond RA, et al. : An intervention to reduce vaginal douching among adolescent and young adult women: A randomized, controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32(12):752–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher JD. and Fisher WA: Theoretical Approaches to Individual Level Change in HIV Risk Behavior. Kluwer Academics/Plenum, New York, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM Jr, et al. : Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. JAMA 1998;280(13):1161–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher JD. and Fisher WA, Eds. Theoretical Approaches to Individual Level Change in HIV Risk Behavior. Handbook of HIV Prevention. Kluwer Academic/Plenum, New York, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Harlow LL, et al. : The transtheoretical model of change and HIV prevention: A review. Health Educ Q 1994;21(4):471–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher WA, Fisher JD, and Harman J: The information-motivation-behavioral skills model: A general social psychological approach to understanding and promoting health behavior. In: Social Psychological Foundations of Health and Illness (Suls J, Wallston KA, eds.). Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Malden, MA, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masese L, McClelland RS, Gitau R, et al. : A pilot study of the feasibility of a vaginal washing cessation intervention among Kenyan female sex workers. Sex Transm Infect 2013;89(3):217–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, and Hillier SL: Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol 1991;29(2):297–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheth PM, Danesh A, Shahabi K, et al. : HIV-specific CD8+lymphocytes in semen are not associated with reduced HIV shedding. J Immunol 2005;175(7):4789–4796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, et al. : Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108(Suppl 1):4680–4687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. : QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 2010;7(5):335–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsen FA, Kodner RB, and Armbrust EV: pplacer: Linear time maximum-likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic placement of sequences onto a fixed reference tree. BMC Bioinformatics 2010;11:538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gajer P, Brotman RM, Bai G, et al. : Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Sci Transl Med 2012;4(132):132ra152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cicala C, Martinelli E, McNally JP, et al. : The integrin alpha4beta7 forms a complex with cell-surface CD4 and defines a T-cell subset that is highly susceptible to infection by HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106(49):20877–20882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waruiru W, Kim AA, Kimanga DO, et al. : The Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2012: Rationale, methods, description of participants, and response rates. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66(Suppl 1):S3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masese L, McClelland RS, Gitau R, et al. : A pilot study of the feasibility of a vaginal washing cessation intervention among Kenyan female sex workers. Sex Transm Infect 2013;89(3):217–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brotman RM, Ghanem KG, Klebanoff MA, et al. : The effect of vaginal douching cessation on bacterial vaginosis: A pilot study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198(6):628e621–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferris MJ, Masztal A, Aldridge KE, et al. : Association of Atopobium vaginae, a recently described metronidazole resistant anaerobe, with bacterial vaginosis. BMC Infect Dis 2004;4:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macklaim JM, Gloor GB, Anukam KC, et al. : At the crossroads of vaginal health and disease, the genome sequence of Lactobacillus iners AB-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108(Suppl 1):4688–4695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, et al. : Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. AIDS 2006;20(1):73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klebanoff MA, Andrews WW, Yu KF, et al. : A pilot study of vaginal flora changes with randomization to cessation of douching. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33(10):610–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.