Abstract

Objectives

Bipolar disorder (BPD) affects more than 2 million adults in the USA and ranks among the top 10 causes of worldwide disabilities. Despite its prevalence, very little is known about the etiology of BPD. Recent evidence suggests that cellular energy metabolism is disturbed in BPD. Mitochondrial function is altered, and levels of high-energy phosphates, such as phosphocreatine (PCr), are reduced in the brain. This evidence has led to the hypothesis that deficiencies in energy metabolism could account for some of the pathophysiology observed in BPD. To further explore this hypothesis, we examined levels of creatine kinase (CK) mRNA, the enzyme involved in synthesis and metabolism of PCr, in the hippocampus (HIP) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) of control, BPD and schizophrenia subjects.

Methods

Tissue was obtained from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (HIP, DLPFC) and gene expression microarrays (HIP) were employed to compare the brain and mitochondrial 1 isoforms of CK.

Results

Both CK isoforms were downregulated in BPD. Furthermore, mRNA transcripts for oligodendrocyte-specific proteins were downregulated in the DLPFC, whereas the mRNA for the neuron-specific protein microtubule-associated protein 2 was downregulated in the HIP.

Conclusion

Although some of the downregulation of CK might be explained by cell loss, a more general mechanism seems to be responsible. The downregulation of CK transcripts, if translated into protein levels, could explain the reduction of high-energy phosphates previously observed in BPD.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, creatine kinase, glia, hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, schizophrenia

Bipolar disorder (BPD) is a common and severe mood disorder that affects more than 2 million adults in the USA (1, 2). BPD is associated with increased risk of suicide and a high socioeconomic burden. Although the clinical features of BPD have long been recognized (3), the disease mechanism(s) remain(s) unknown (4), and treatment resistance is high (1, 5).

Recent studies suggest altered energy metabolism and mitochondrial pathology in BPD (6, 7). Spectroscopic studies have shown a decrease in both pH and high-energy phosphates, such as phosphocreatine (PCr) and ATP, in the frontal and temporal lobes of bipolar subjects (8–11); postmortem studies in the human hippocampus (HIP) of BPD subjects showed a decrease in the expression of nuclear genes coding for mRNAs of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (12); and studies in lymphoblastoid cell lines showed a downregulation of the mitochondrial complex I subunit gene, NDUFV2 (24-kDa subunit of the mitochondrial NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase), and different haplotype frequencies of four polymorphisms in the upstream region of NDUFV2 (13, 14).

Creatine kinase (CK) is the enzyme responsible for the reversible transfer of the N-phosphoryl group from PCr to ADP to yield ATP and creatine (Cr) (15–17). In tissues with high energy demands, such as the brain, CK serves two purposes: the first is to shuttle phosphate groups from the site of energy production, the mitochondria, to sites of energy consumption, such as ATP-dependent ion pumps and neurotransmitter transporters in neurons and glia (18). The second function is to retrieve ATP from PCr during periods of intense energy demand (16). Four CK isoforms are expressed in humans: the first two, brain (CKB) and muscle (CKM), are the cytosolic CK isoenzymes, which are found as homo- or heterodimers at sites of energy consumption; the other two are the mitochondrial isoforms, mitochondrial 1 ubiquitous (CKMt1), and mitochondrial 2 sarcomeric (17). In the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and HIP, the principal CK isoforms are CKB (as the homomer CK-BB) and CKMt1 (19, 20). CKB is expressed at high levels in oligodendrocytes and astroglia and to a lesser extent in neurons, while CKMt1 is expressed in the mitochondria of all cell types, but with the highest levels in neurons (20, 21).

Given the reduced PCr levels observed in magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies (11, 22), we decided to examine the expression levels of mRNA transcripts coding for CKB and CKMt1 in the DLPFC and HIP in the postmortem brain of BPD, schizophrenia (SZ), and control subjects.

Materials and methods

Sample selection and tissue processing

Gene regulation was examined by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reation (PCR) (qPCR; HIP, DLPFC) and by microarrays (HIP) in three study groups: healthy controls, subjects with BPD, and subjects with SZ. Brain specimens were obtained from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (HBTRC; McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA). Subjects were matched for age, postmortem interval, gender, brain hemisphere and storage time. All diagnoses were established by two psychiatrists at the HBTRC via retrospective review of all available medical records and extensive questionnaires about social and medical history completed by family members of the donors. The criteria of Feighner et al. (23) were applied for the diagnosis of SZ and that of the DSM-IV (24) for the diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder and BPD. Probands with a documented history of substance dependence or neurological illness were excluded from the study.

One hemisphere of each brain underwent a comprehensive neuropathological examination, and only brains with no evidence of stroke, tumor, infection, or neurodegenerative changes were used in the study. Microarray analysis of the HIP was carried out in 10 control subjects, 9 subjects with BPD, and 8 subjects with schizophrenia (12). For qPCR of the HIP, an independent RNA extraction was performed on samples for which tissue was still available at the HBTRC, yielding seven triplets (control, BPD, SZ; Table 1). For qPCR analysis of the DLPFC, nine controls, nine BPD subjects, and eight SZ subjects were obtained (Table 1). For procedures of the HBTRC see http://www.brainbank.mclean.org/.

Table 1.

Demographics of the subjects used in the study

| Case no. |

Sex /age |

Diagnosis | Hemisphere | Postmortem interval (h) |

Cause of death |

Chlorpromazine equivalents (mg) |

Psychoactive medication use |

qPCR brain area |

pH cerebellum |

Hippocampus microarray data

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3′/5′ GAPDH |

3′/5′ B-Actin |

Present calls |

Scaling factor |

Back- ground level |

28S /18S |

||||||||||

| 4605 | M/29 | NA (control) | L | 18.2 | Renal failure | NA | NA | HIP, PFC | 7.1 | 2 | 2.5 | 43.4 | 2.5 | 51 | 1.44 |

| 4737 | F/74 | NA (control) | L | 12.5 | Renal failure | NA | NA | HIP, PFC | 6.3 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 37.3 | 3.82 | 49 | 0.34 |

| 4751 | M/54 | NA (control) | L | 24.2 | Cardiac arrest | NA | NA | HIP, PFC | 6.5 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 47.1 | 1.85 | 56 | 1.44 |

| 5074 | M/79 | NA (control) | R | 20.9 | Pancreatic cancer | NA | NA | HIP, PFC | 6.7 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 48.3 | 2 | 46 | 0.92 |

| 3806 | F/70 | NA (control) | R | 15 | Cardiac arrest | NA | NA | HIP | 6.6 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 45.1 | 2.27 | 49 | 1 |

| 3898 | F/78 | NA (control) | R | 14.1 | Myocardial infarction | NA | NA | HIP, PFC | 6.2 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 45 | 2.16 | 50 | 0.85 |

| 5082 | F/78 | NA (control) | R | 23.9 | Breast cancer | NA | NA | HIP, PFC | 6.7 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 45.4 | 2.18 | 65 | 1.25 |

| 4853 | F/70 | NA (control) | L | 22.5 | Liver cancer | NA | NA | PFC | 6.3 | 2 | 2.6 | 43.3 | 3.1 | 45 | 1.03 |

| 4932 | M/67 | NA (control) | R | 22.3 | Cardiac arrest | NA | NA | PFC | 6.4 | 1.5 | 2 | 47.4 | 1.74 | 47 | 1.3 |

| 4810 | F/62 | NA (control) | L | 16.4 | Lung cancer | NA | NA | PFC | nd | 1.6 | 2.1 | 45.9 | 2.39 | 46 | 1.11 |

| 4069 | F/80 | Bipolar disorder | L | 11.6 | Cerebrovascular accident | 67 | Perphenazine, benztropine, valproate | HIP, PFC | 6.5 | 2 | 2.6 | 44.9 | 1.98 | 49 | 1.21 |

| 4403 | F/76 | Bipolar disorder | L | 22.8 | Cardiopulmonary failure | 0 | Lithium carbonate | HIP, PFC | 6.6 | 2.5 | 3 | 41.3 | 3.49 | 46 | 0.54 |

| 4462 | M/50 | Bipolar disorder | R | 30.5 | Cardiac arrest | NA | ? | HIP, PFC | 6.4 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 42 | 2.7 | 50 | 0.77 |

| 4661 | M/25 | Bipolar disorder | L | 12.6 | Pulmonary edema | 0 | Sertraline, trazodone, gabapentin, lithium | HIP, PFC | 6.7 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 39 | 3.01 | 52 | 1 |

| 3817 | F/64 | Bipolar disorder | R | 11 | Respiratory failure | 800 | Trifluoperazine | HIP, PFC | 6.7 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 46.3 | 2.25 | 46 | 0.56 |

| 4464 | M/74 | Bipolar disorder | L | 24.8 | Pneumonia | 285 | Divalproex sodium, quetiapine | HIP, PFC | 6.5 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 39.1 | 5.61 | 39 | 0.67 |

| 4961 | M/74 | Bipolar disorder | R | 14.3 | Pneumonia | 0 | Lithium, divalproex sodium | HIP, PFC | 6.3 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 42.2 | 2.55 | 44 | 1.04 |

| 4914 | F/73 | Bipolar disorder | R | 20.8 | Sepsis | 33 | Risperidone, carbamazepine | PFC | 6.3 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 42.9 | 2.85 | 48 | 1.03 |

| 5044 | F/73 | Bipolar disorder | R | 17 | Renal failure | 133 | Lithium | PFC | 6.4 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 28.6 | 3.43 | 52 | 0.33 |

| 4190 | F/78 | Schizoaffective disorder | L | 13.4 | Sinus node disease | 1066 | Lithium, haloperidol | HIP, PFC | 6.8 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 44.1 | 2.02 | 46 | 1.33 |

| 4875 | F/55 | Schizoaffective disorder | R | 18 | Cancer | 200 | Divalproex sodium, intramuscular fluphenazine | HIP, PFC | 6.5 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 47.7 | 2.22 | 46 | 1.17 |

| 5047 | M/63 | Schizophrenia | R | 22.3 | Cardiac arrest | 532 | Clozapine, clonazapam | HIP, PFC | nd | 2.4 | 3.8 | 40 | 3.12 | 52 | 0.91 |

| 5100 | F/72 | Schizophrenia | R | 21.7 | Cancer | 267 | Risperidone, benztropine, paroxetine | HIP, PFC | 6.7 | 1.5 | 2 | 47.4 | 2.1 | 49 | 1.09 |

| 4469 | M/80 | Schizophrenia | L | 11 | Cardiopulmonary failure | 10 | Thioridazine | HIP, PFC | 6.4 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 47.1 | 1.96 | 49 | 1.44 |

| 4907 | F/73 | Schizoaffective disorder | R | 24 | Lung cancer | 600 | Prolixin | HIP, PFC | 6.1 | 3 | 2.8 | 38 | 3.82 | 47 | 0.67 |

| 4238 | M/26 | Schizophrenia | R | 16 | Suicide by hanging | 357 | Prolixin decanoate | HIP, PFC | 6.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 47.4 | 1.36 | 51 | 1.23 |

| 5115 | M/49 | Schizophrenia | L | 24.5 | Acute respiratory failure | 1066 | Haloperidol decanoate | PFC | nd | 1.5 | 1.6 | 47.1 | 1.8 | 48 | 1.22 |

| Summary

| |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Sex/age | Hemisphere | Postmortem interval (h)* |

Storage time (W)* |

pH cerebellum* |

3′/5′ GAPDH* |

3 ′/5′ B-Actin* |

Present calls* |

Scaling factor* |

Background level* |

28S/18S* |

| PFC qPCR | |||||||||||

| Control | 4M, 5F/66 ± 5 | 5L, 4R | 19.4 ± 1.4 | 219.6 ± l7.5 | 6.53 ± 0.10 | ||||||

| Bipolar disorder | 4M, 5F/65 ± 6 | 5L, 4R | 18.4 ± 2.3 | 253.0 ± 20.8 | 6.49 ± 0.05 | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 4M, 4F/62 ± 6 | 3L, 5R | 18.9 ± 1.8 | 228.4 ± 19.9 | 6.55 ± 0.11 | ||||||

| HIP qPCR | |||||||||||

| Control | 3M, 4F/66 ± 7 | 3L, 4R | 18.4 ± 1.8 | 246.5 ± 28.9 | 6.59 ± 0.11 | ||||||

| Bipolar disorder | 4M, 3F/63 ± 7 | 4L, 3R | 18.2 ± 2.9 | 272.7 ± 21.1 | 6.53 ± 0.06 | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 3M, 4F/64 ± 7 | 2L, 5R | 18.1 ± 1.8 | 237.6 ± 20.4 | 6.55 ± 0.11 | ||||||

| Microarray | |||||||||||

| Control | 4M, 6F/66 ± 5 | 5L, 5R | 19.0 ± 1.4 | 129.1 ± 20.9 | 6.53 ± 0.09 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 44.8 ± 1.0 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 50.4 ± 1.9 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| Bipolar disorder | 4M, 5F/65 ± 6 | 5L, 4R | 18.4 ± 2.3 | 148.6 ± 20.8 | 6.49 ± 0.05 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 40.7 ± 1.7 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 47.3 ± 1.4 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| Schizophrenia | 4M, 4F/62 ± 6 | 3L, 5R | 18.9 ± 1.8 | 124.0 ± 19.9 | 6.55 ± 0.11 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 44.9 ± 1.4 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 48.5 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

HIP = hippocampus; PFC = prefrontal cortex; qPCR = quantitative real-time PCR.

Average ± SEM.

Treatment of rats and processing of rat tissue

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY, USA), 200–225 g, were fed 0.15% lithium carbonate chow or control chow balanced for nutrient content (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI, USA). The colony room was maintained on a 12-h light–dark cycle. Rats were provided water and 450 mM NaCl solution. On day 15 of lithium chow, rats were decapitated, brains removed and immediately frozen in isopentane/dry ice. Hippocampi were dissected on a freezing microtome, and RNA was extracted and prepared for gene expression microarray analysis applying the same protocol used for the human studies.

Gene array data analysis

Affymetrix HG-U95Av2 arrays were used in the human study, and RAE230A arrays were used in the rat study. (For specifics of tissue and RNA preparation for the Affymetrix GeneChips see 12, 25.) RMAexpress was used for background adjustment, normalization, and computation of gene expression summary values (http://stat-www.berkeley.edu/users/bolstad/RMAExpress/RMAExpress.html), (26, 27). The dChip program (http://www.dchip.org) (28) and GenMAPP (http://www.genmapp.org) (29) were used for further analysis. Recent work on the standardization of microarray experiments indicates that there is good reproducibility across different laboratories, sometimes as good as 90% (30) especially with the Affymetrix platform (30–32).

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

For qPCR, complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA (SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for real-time quantitative PCR; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with oligonucleotide deoxythymidine primers. A primer set for each gene was designed with the help of Primer3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi). Amplicons were designed to be between 150 and 250 bp in length. Melt Curve analysis and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis were used to confirm the specificity of each primer pair. Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out with the DyNAmo HS SYBR Green real-time quantitative PCR kit (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) in a volume of 20 μL, with cDNA equivalent to ≈ 40 ng total RNA, 10 μL DyNAmo HS master mix, 0.3 μM each of forward and reverse primer and ultrapure water (Invitrogen). The PCR cycling conditions were 95°C for 7 min followed by 39 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 55°C for 15 s, 72°C for 20 s, and 73–82°C (depending on product melt temperature) for 2 s. A melt curve analysis was performed at the end of each PCR experiment to verify product specificity for each reaction. Dilution curves were generated for each experiment by diluting cDNA four times from a control sample with a ratio of 1:5, yielding a dilution series of 1.00, 0.2, 0.04, 0.008, and 0.0016. The logarithm of the dilution value was plotted against the cycle threshold value to give a standard curve. Blanks were included in each dilution curve to control for cross-contamination. Dilution curves, blanks, and samples were assayed in duplicates on the same plate. Reported values were normalized to the internal control human filamin A alpha (Table 2), an actin binding protein that was not regulated in the gene array experiment or the qPCR analysis.

Table 2.

Accession numbers of human genes evaluated in the study

| Common name | Abbreviation | Accession number |

|---|---|---|

| Creatine kinase, brain | CKB | NM_001823 |

| Creatine kinase, mitochondrial 1 | CKMt1 | NM_020990 |

| Doublecortin | DCX | NM_000555 |

| Erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 3 | ERBB3 | NM_001982 |

| Gelsolin | GSN | NM_000177 |

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein | GFAP | NM_002055 |

| Filamin A, alpha (actin-binding protein 280) | FLNA | NM_001456 |

| Microtubule-associated protein 2 | MAP2 | NM_031845 |

| Myelin-associated glycoprotein | MAG | NM_002361 |

| Myelin-associated oligodendrocyte basic protein | MOBP | NM_006501 |

Results

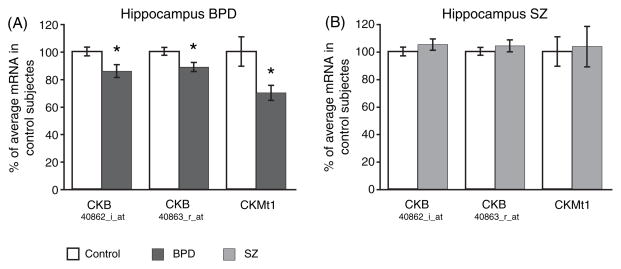

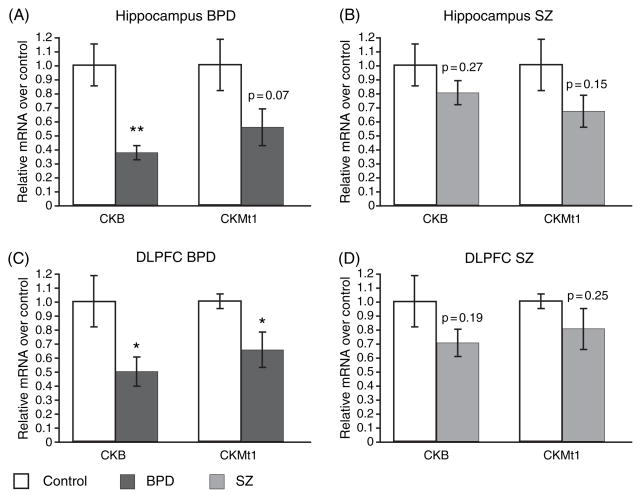

Microarray data revealed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) of the CKB and CKMt1 transcript in the HIP in BPD (Fig. 1A) but not in SZ (Fig. 1B). To further examine the expression levels of the CK isoforms in BDP and SZ, qPCR was performed on postmortem tissue from the DLPFC and HIP. A subset of the same samples used to generate the microarray data was used for qPCR analysis, and downregulations of CKB and CKMt1 (p = 0.07; not significant) was confirmed in the HIP in BPD (Fig. 2A), in contrast to SZ (Fig. 2B). Moreover, similar downregulations of CKB and CKMt1 were observed in the DLPFC in BPD (Fig. 2C), but not in SZ (Fig. 2D). However, the data indicate that SZ brains might follow a similar, albeit weaker, trend. Power analysis revealed that a sample size of 26 (CKMt1) to 44 (CKB) samples could potentially yield significant downregulations of CK isoforms in the HIP in SZ, and a sample size of 33 (CKB) to 43 (CKMt1) in the DLPFC.

Fig. 1.

Gene expression microarray data from the human hippocampus of (A) bipolar disorder (BPD) and (B) schizophrenia (SZ) subjects. CKB is represented twice on the HG-U95Av2 array and identified by the respective probe set number. Relative mRNA levels in percentage of control are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction data verified the gene expression microarray findings in the hippocampus in (A) bipolar disorder (BPD) and (B) schizophrenia (SZ) subjects. The downregulation of CK isoforms was furthermore extended to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in BPD subjects (C). No significant downregulation was observed in the DLPFC in SZ subjects (D) with the sample size available. Relative mRNA levels of experiment (BPD or SZ corrected for internal standard, filamin A) over control (corrected for internal standard) are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

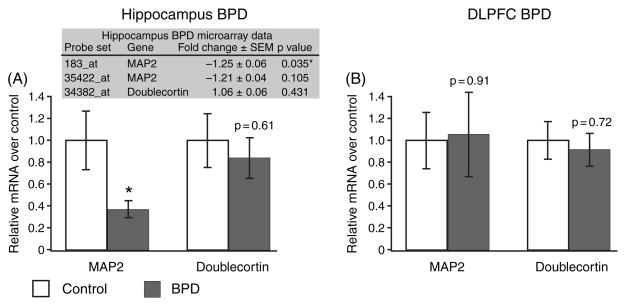

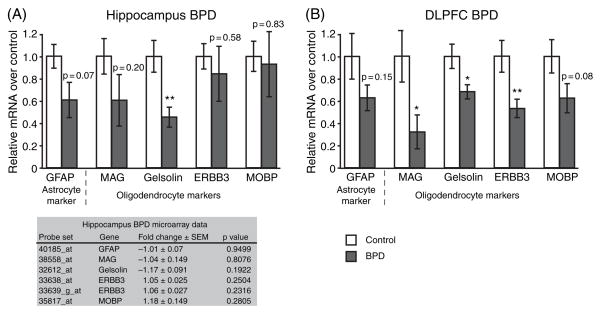

CKMt1 is expressed predominantly in neurons, while CKB is expressed predominantly in oligodendrocytes and astrocytes (20, 21, 33). Because some studies of BPD have shown a reduction in glial markers and glial density (34–36) and others have shown a reduction in neuronal size and number (36– 38), the downregulation of CKB might be a consequence of glial loss, or, conversely, the downregulation of CKMt1 might indicate neuronal cell loss. Therefore, we used qPCR to examine expression levels of markers for astrocytes (glial fibrillary acidic protein), oligodendrocytes (myelin-associated glycoprotein; gelsolin, v-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 3, ERBB3; and myelin basic protein) and neurons (doublecortin and microtubule-associated protein 2, MAP2) in the HIP (Fig. 3A) and DLPFC (Fig. 3B). Doublecortin was similar to control in both brain areas, whereas in the HIP, MAP2 was downregulated. The data imply that the downregulation of CKMt1 in the DLPFC is not due to neuronal cell death, but leaves the question open for the HIP (Fig. 4). In agreement with previous observations, several oligodendrocyte markers were significantly downregulated in the DLPFC in BPD(Fig. 3; 34). Thus, it cannot be ruled out that the downregulation of CKB in the DLPFC in BPD was augmented by a decrease of the glial cell population.

Fig. 3.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction experiments show that (A) the level of the MAP2 transcript, a gene specifically expressed in neurons, is downregulated in the hippocampus in bipolar disorder (BPD) subjects. Doublecortin, another neuron-specific transcript, is unchanged. (B) Neuronal markers are expressed at control level in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). The shaded table in (A) shows the gene expression data from the microarray study in the hippocampus. MAP2 was represented twice on the array, and one probe set was significantly downregulated. Relative mRNA levels of BPD (corrected for the internal standard, filamin A) over control (corrected for internal standard) are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

Fig. 4.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction experiments were carried out for glial transcripts. (A) A downregulation of gelsolin was observed in the hippocampus, but other markers were unchanged. (B) Three of four markers were significantly downregulated in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in bipolar disorder (BPD) subjects. The shaded table in (A) shows the gene expression data from the microarray study in the hippocampus. Relative mRNA levels of BPD (corrected for the internal standard, filamin A) over control (corrected for internal standard) are shown as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

In order to examine the potential effect of mood stabilizers on the expression of transcripts of CKB, CKMt1 and neuronal and glial markers, we fed rats lithium chow for 15 days and performed a gene expression microarray analysis (Table 3). Except for ERBB3, no significant changes were found, suggesting that treatment might not be responsible for the observed findings.

Table 3.

Gene expression microarray results in rat HIP with lithium chow for 15 days. Transcripts with more than one probe set on the array (RAE230A) are shown in all their representations.

| Locus Link ID | Gene name | Affymetrix ID | Fold change | p-value | P call % (control) | P call % (lithium) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24264 | Creatine kinase, brain | 1367740_at | 1.1 | 0.239497 | 100 | 100 |

| 29593 | Creatine kinase, mitochondrial 1, ubiquitous | 1390566_a_at | 1 | 0.991371 | 100 | 100 |

| 84394 | Doublecortin | 1374966_at | −1.04 | 0.651172 | 12 | 0 |

| 84394 | Doublecortin | 1387601_at | −1.04 | 0.319053 | 0 | 0 |

| 25595 | Microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) | 1368411_a_at | −1.22 | 0.202223 | 100 | 100 |

| 25595 | Microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) | 1388152_at | −1.15 | 0.149025 | 100 | 100 |

| 296654 | Gelsolin | 1371414_at | 1.04 | 0.630259 | 100 | 100 |

| 24387 | Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) | 1368353_at | 1.06 | 0.439748 | 100 | 100 |

| 24547 | Myelin basic protein (MBP) | 1368810_a_at | −1.09 | 0.110849 | 100 | 100 |

| 24547 | Myelin basic protein (MBP) | 1387341_a_at | −1.11 | 0.413766 | 100 | 100 |

| 29409 | Myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) | 1368861_a_at | −1.14 | 0.213108 | 100 | 100 |

| 29496 | ERBB3 | 1369088_at | −1.07 | 0.367392 | 25 | 0 |

| 29496 | ERBB3 | 1377821_at | −1.3 | 0.003336 | 100 | 100 |

Discussion

The Cr shuttle plays a critical role in cellular energy storage and regulation (15, 16, 39), and research suggests that BPD might be accompanied by reduced PCr levels and altered mitochondrial function. Spectroscopic imaging studies have shown reductions of PCr in BPD and depression (8, 11, 22, 40–43). In a study of geriatric depression, remission was accompanied by an increase in PCr concentration (40). The decreased PCr concentration observed in BPD was interpreted to be a result of mitochondrial dysfunction (11). This interpretation was based on increased lactate levels observed in BPD subjects, as increases in lactate levels are associated with mitochondrial myopathies and other syndromes of energy impairment (44). Concordant with this interpretation, a downregulation of nuclear mRNAs coding for proteins of the mitochondrial respiratory chain was observed in the HIP in BPD subjects (12). In this study we demonstrate that transcripts of CK isoforms are downregulated in the same patients that showed a downregulation of genomic mitochondrial transcripts (12), raising the possibility that the reductions in PCr levels and downregulations of CK and mitochondrial respiratory chain transcripts are linked.

It has been demonstrated that mice lacking CKB exhibit diminished open-field habituation and delayed acquisition of spatial tasks (45), while mice lacking CKMt display a reduced acoustic startle response and lack of prepulse inhibition in addition to the deficits seen in CKB knockout mice (46, 47). These mice did not show any gross abnormalities of brain structure or of mitochondrial ultrastructure; in fact, the mice were ‘overtly normal’ and ‘rather sophisticated analysis and challenging conditions were needed to reveal (these deficits)’ (48). Thus, while the complete removal of a CK isoform does produce measurable behavioral deficits, it does not create overt symptoms, and a downregulation of CK transcripts, if translated into lower protein levels, might produce a subtle pathology that could be compatible with BPD.

In contrast to the decreased expression of CK mRNA observed in our study in the brain, increased levels of CK protein were observed in cerebrospinal fluid and serum of BPD patients immediately after an acute episode (49–51). Increased serum levels of CK protein are likely the muscle isoform and may indicate muscle damage (52, 53); however, studies have shown that isometric muscle tension cannot account for the large spike in serum CK protein levels following an elevated state in BPD and SZ (54). Increased CNS levels of CK protein might indicate cell death in the brain (49, 55–57). Our data cannot refute a hypothesis of neuronal cell death in the HIP or loss of glia in the DLPFC leading to increased CK protein during an acute episode, and decreased levels of CK mRNA due to lower cell numbers after the episode and in the euthymic state. A reduction in glial cell population would also have an adverse effect on the Cr shuttle system, since only oligodendrocytes and astroglia express the enzyme responsible for Cr synthesis, suggesting that glia supplies neurons with Cr (20).

However, cell death is not a satisfactory explanation for reduced CK mRNA levels. First, the particular distribution of CKB and CKMt1 between neurons and glia would suggest that a loss of neurons should be mostly evident as a loss of CKMt1 transcripts, whereas a loss of glia would be reflected in a loss of CKB transcripts. Loss of one cell type would lead to a relative increase in the remaining cell type in a given sample, thus decrease in one CK type should lead to an increase in the other. We did see both isoforms reduced in both brain areas. Second, the level of only one of two neuron-specific genes, MAP2, was reduced in the HIP, thus providing weak support for cell death in this brain area. While we cannot exclude that cell death might be contributing to the reduced transcript levels of CK isoforms, the data point more likely to a generalized disturbance of energy regulation in BPD.

Although we took great care in matching the samples, human postmortem studies offer only limited experimental control. We excluded subjects who died under respiratory distress, were on a ventilator or had otherwise prolonged agonal events, but variability in mode of death beyond our control could have influenced the results. Disease-specific treatment is another concern: because BPD patients were treated with mood stabilizers, we examined in a rat model if lithium treatment affects transcript levels of CK isoforms in the HIP. Lithium treatment did not affect CK transcript levels nor transcript levels of neuronal or glial genes, although we did find a downregulation of ERBB3. However, ERBB3 was represented by two different probe sets on the array, only one of which was changed. Because of this discrepancy, because ERBB3 was only one of five glial-specific transcripts, and because ERBB3 was not altered in the human HIP, we conclude that treatment with mood stabilizers is not responsible for the observed downregulations of glial- and neuron-specific transcripts, nor of CK.

Our data lend further support to altered energy systems in BPD. Whether this change is cause or consequence of the disorder cannot be deduced from the results. However, the question of cause and consequence might not be of major significance for treatment strategies, since a negative impact, be it primary or secondary, would always benefit from treatment. In conclusion, the ‘energy hypothesis of BPD’ deserves closer scrutiny and further examination as it has the potential to alter therapeutic approaches to the disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Jim and Pat Poitras. The authors thank Stephan Heckers, MD, MS, Francine Benes, MD, PhD, and John Walsh, MS, for their help, and Theo Wallimann, PhD, for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

The authors of this paper do not have any commercial associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Post RM, Leverich GS, Altshuler LL, et al. An overview of recent findings of the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network (Part I) Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:310–319. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar Disorder. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; Baltimore: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraepelin E. Psychiatry: A Text Book for Students and Physicians. Canton, MA: Science History Publications; 1899. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowan WM, Kopnisky KL, Hyman SE. The human genome project and its impact on psychiatry. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:1–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gnanadesikan M, Freeman MP, Gelenberg AJ. Alternatives to lithium and divalproex in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:203–216. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato T, Kato N. Mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2:180–190. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hough CJ, Chuang DM. The mitochondrial hypothesis of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2:145–147. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato T, Takahashi S, Shioiri T, Inubushi T. Alterations in brain phosphorous metabolism in bipolar disorder detected by in vivo 31P and 7Li magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Affect Disord. 1993;27:53–59. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato T, Inubushi T, Kato N. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in affective disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;10:133–147. doi: 10.1176/jnp.10.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deicken RF, Weiner MW, Fein G. Decreased temporal lobe phosphomonoesters in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 1995;33:195–199. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)00089-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dager SR, Friedman SD, Parow A, et al. Brain metabolic alterations in medication-free patients with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:450–458. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konradi C, Eaton M, MacDonald ML, Walsh J, Benes FM, Heckers S. Molecular evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:300–308. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Washizuka S, Kakiuchi C, Mori K, et al. Association of mitochondrial complex I subunit gene NDUFV2 at 18p11 with bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet. 2003;120B:72–78. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Washizuka S, Iwamoto K, Kazuno A-a, et al. Association of mitochondrial complex I subunit gene NDUFV2 at 18p11 with bipolar disorder in Japanese and the National Institute of Mental Health pedigrees. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallimann T, Dolder M, Schlattner U, et al. Creatine kinase: an enzyme with a central role in cellular energy metabolism. MAGMA. 1998;6:116–119. doi: 10.1007/BF02660927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallimann T, Wyss M, Brdiczka D, Nicolay K, Eppenberger HM. Intracellular compartmentation, structure and function of creatine kinase isoenzymes in tissues with high and fluctuating energy demands: the ‘phosphocreatine circuit’ for cellular energy homeostasis. Biochem J. 1992;281:21–40. doi: 10.1042/bj2810021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wyss M, Kaddurah-Daouk R. Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1107–1213. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallimann T, Schlattner U, Guerrero L, Dolder M. The phospho-creatine circuit and creatine supplementation come of age! In: Mori A, Ishida M, Clark JF, editors. Guanidino Compounds in Biology and Medicine. Vol. 5. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1999. pp. 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamburg RJ, Friedman DL, Olson EN, et al. Muscle creatine kinase isoenzyme expression in adult human brain. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6403–6409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tachikawa M, Fukaya M, Terasaki T, Ohtsuki S, Watanabe M. Distinct cellular expressions of creatine synthetic enzyme GAMT and creatine kinases uCK-Mi and CK-B suggest a novel neuron-glial relationship for brain energy homeostasis. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:144–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallimann T, Hemmer W. Creatine kinase in non-muscle tissues and cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;134:193–220. doi: 10.1007/BF01267955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato T, Takahashi S, Shioiri T, Murashita J, Hamakawa H, Inubushi T. Reduction of brain phosphocreatine in bipolar II disorder detected by phosphorus- 31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Affect Disord. 1994;31:125–133. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA, Jr, Winokur G, Munoz R. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;26:57–63. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750190059011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DSM-IV. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacDonald ML, Eaton ME, Dudman JT, Konradi C. Antipsychotic drugs elevate mRNA levels of presynaptic proteins in the frontal cortex of the rat. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1041–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Wong WH. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:31–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahlquist KD, Salomonis N, Vranizan K, Lawlor SC, Conklin BR. GenMAPP, a new tool for viewing and analyzing microarray data on biological pathways. Nat Genet. 2002;31:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng0502-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larkin JE, Frank BC, Gavras H, Sultana R, Quackenbush J. Independence and reproducibility across microarray platforms. Nat Methods. 2005;2:337–344. doi: 10.1038/nmeth757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Irizarry RA, Warren D, Spencer F, et al. Multiple-laboratory comparison of microarray platforms. Nat Methods. 2005;2:345–350. doi: 10.1038/nmeth756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bammler T, Beyer RP, Bhattacharya S, et al. Standardizing global gene expression analysis between laboratories and across platforms. Nat Methods. 2005;2:351–356. doi: 10.1038/nmeth754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molloy GR, Wilson CD, Benfield P, de Vellis J, Kumar S. Rat brain creatine kinase messenger RNA levels are high in primary cultures of brain astrocytes and oligodendrocytes and low in neurons. J Neurochem. 1992;59:1925–1932. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb11028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tkachev D, Mimmack ML, Ryan MM, et al. Oligodendrocyte dysfunction in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2003;362:798–805. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ongur D, Drevets WC, Price JL. Glial reduction in the subgenual prefrontal cortex in mood disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13290–13295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajkowska G, Halaris A, Selemon LD. Reductions in neuronal and glial density characterize the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:741–752. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cotter D, Mackay D, Chana G, Beasley C, Landau S, Everall IP. Reduced neuronal size and glial cell density in area 9 of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in subjects with major depressive disorder. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:386–394. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajkowska G. Cell pathology in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:105–116. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neumann D, Schlattner U, Wallimann T. A molecular approach to the concerted action of kinases involved in energy homoeostasis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:169– 174. doi: 10.1042/bst0310169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pettegrew JW, Levine J, Gershon S, et al. 31P-MRS study of acetyl-L-carnitine treatment in geriatric depression: preliminary results. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:61–66. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Volz HP, Rzanny R, Riehemann S, et al. 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the frontal lobe of major depressed patients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;248:289–295. doi: 10.1007/s004060050052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore CM, Frederick BB, Renshaw PF. Brain biochemistry using magnetic resonance spectroscopy: relevance to psychiatric illness in the elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1999;12:107–117. doi: 10.1177/089198879901200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cecil KM, DelBello MP, Sellars MC, Strakowski SM. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the frontal lobe and cerebellar vermis in children with a mood disorder and a familial risk for bipolar disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13:545–555. doi: 10.1089/104454603322724931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kerr DS. Lactic acidosis and mitochondrial disorders. Clin Biochem. 1991;24:331–336. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(91)80007-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jost CR, Van Der Zee CE, In ‘t Zandt HJ, et al. Creatine kinase B-driven energy transfer in the brain is important for habituation and spatial learning behaviour, mossy fibre field size and determination of seizure susceptibility. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:1692–1706. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Streijger F, Oerlemans F, Ellenbroek BA, Jost CR, Wieringa B, Van der Zee CE. Structural and behavioural consequences of double deficiency for creatine kinases BCK and UbCKmit. Behav Brain Res. 2004;157:219–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Streijger F, Jost CR, Oerlemans F, et al. Mice lacking the UbCKmit isoform of creatine kinase reveal slower spatial learning acquisition, diminished exploration and habituation, and reduced acoustic startle reflex responses. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004:305–318. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000009877.90129.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.in‘t Zandt HJ, Renema WK, Streijger F, et al. Cerebral creatine kinase deficiency influences metabolite levels and morphology in the mouse brain: a quantitative in vivo 1H and 31P magnetic resonance study. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1321–1330. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vale S, Espejel MA, Calcaneo F, Ocampo J, Diaz-de-Leon J. Creatine phosphokinase. Increased activity of the spinal fluid in psychotic patients. Arch Neurol. 1974;30:103–104. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1974.00490310105017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manor I, Hermesh H, Valevski A, Benjamin Y, Munitz H, Weizman A. Recurrence pattern of serum creatine phosphokinase levels in repeated acute psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43:288–292. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor JR, Abichandani L. Creatine phosphokinase elevations and psychiatric symptomatology. Biol Psychiatry. 1980;15:865–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meltzer H. Muscle enzyme release in the acute psychoses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1969;21:102–112. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1969.01740190104015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meltzer HY, Moline R. Muscle abnormalities in acute psychoses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1970;23:481–491. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1970.01750060001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goode DJ, Meltzer HY. Effects of isometric exercise on serum creatine phosphokinase activity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1207–1211. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770100069007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sherwin AL, Norris JW, Bulcke JA. Spinal fluid creatine kinase in neurologic disease. Neurology. 1969;19:993–999. doi: 10.1212/wnl.19.10.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herschkowitz N, Cumings JN. Creatine kinase in cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1964;27:247– 250. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.27.3.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parakh N, Gupta HL, Jain A. Evaluation of enzymes in serum and cerebrospinal fluid in cases of stroke. Neurol India. 2002;50:518–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]