Abstract

Ischemia reperfusion (I/R) injury is a main cause of transplanted kidney dysfunction and rejection. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a causal role in cellular damage induced by I/R. Antioxidant vitamins and Nitric oxide (NO) were postulated to play renoprotective effects against I/R. This study compares the protective effects of vitamin C with that of the nitric oxide donor, L-arginine, on renal I/R injury in adult rats. The study was performed on 50 adult Wistar rats of both sexes, divided into 5 groups: I: Control group, receive daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) saline for 3 days. II: Renal I/R group, received i.p saline for 3 days and subjected to renal I/R. III: L-arginine Pretreated, 400 mg/kg/day i.p. for 3 days prior to I/R. IV: Vitamin C Pretreated, 500 mg/kg/day i.p. 24 hours prior to I/R. V: combined L-arginine and Vitamin C Pretreated, exposed to Renal I/R group. At the end of the experiment, plasma urea and creatinine were determined. Kidney tissue malondialdehyde (MDA), NO, catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity were measured and kidneys were examined histologically. Results: I/R group showed significant increase in plasma urea, creatinine, and renal MDA, and a significant decrease in renal catalase with marked necrotic epithelial cells and infiltration by inflammatory cells in kidney section compared to the control group. All the treated groups showed significant decrease in urea, creatinine, and MDA, and a significant increase in catalase with less histopathological changes in kidney sections compared to I/R group. However, significant improvements in urea, MDA, and catalase were found in vitamin C pretreated and combined treated groups than L-arginine pretreated group. Conclusion: Oxidative stress is the primary element involved in renal I/R injury. So, antioxidants play an important renoprotective effects than NO donors.

Keywords: Renal ischemia/reperfusion, vitamin C, L-arginine, oxidative stress

Introduction

Ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury was one of the main causes of acute kidney injury [1]. Renal I/R injury was also associated with delayed graft function and increased risk of acute rejection in kidney transplantation [2].

Previous studies demonstrated that renal I/R injury caused decrease in renal blood flow by 50 and 75% within 1 day of reperfusion and this was associated with a dramatic rise in serum creatinine [3]. In addition to direct hypoxic damages induced by reductions in blood flow [4], tubular epithelial damage was associated with renal I/R injury and was regenerated by an increase in cell proliferation to replace lost cells, migration and redifferentiation to rebuild the tubule within 2-4 weeks [5]. Alterations in renal structure and function following renal I/R injury could be a predisposing factor in development of renal failure [6].

Increased oxidative stress was a documented finding in renal I/R injury [7]. Previous studies demonstrated that reactive oxygen species (ROS) contributed to tissue damage and the loss of function in I/R injury. Renal I/R increased production of superoxide and other ROS [8].

ROS were generated under different physiological and pathological conditions [9]. Body cells produced small amounts of ROS under physiological conditions; these amounts could be managed by the scavenging capacity of cells. However, in pathological conditions, the production of ROS was increased dramatically, and these large amounts became higher than the capacity to scavenge it [9,10]. The excessive ROS production would be responsible for lipid peroxidation, inactivation of antioxidant enzy-mes, disruptions of the cellular cytoskeleton, breakdown of DNA, leukocyte activation, endothelial cell damage, and cytokine production, and collectively tissue damage [11,12].

Thus, antioxidant agents have been used to prevent tissue damage in various clinical settings and experimental models [13] and could help in preventing the postischemic increases in lipid peroxidation and hydrogen peroxide levels, resulting in reduced kidney injury from I/R [14]. The antioxidant and free radical scavenger ascorbic acid (Vit C) [15] has a protective effect against drug-induced nephrotoxicity in animals [16,17].

In the kidney, various cells, including vascular endothelial and tubular epithelial cells, could generate nitric oxide (NO), which could control renal blood flow and glomerular/tubular functions through interaction with vascular smooth muscle, mesangial, and tubular cells [18,19].

NO had a very important physiological role in the regulation of renal hemodynamics and function. Studies have demonstrated that changes in NO production and/or metabolism in the kidney were closely related to many renal pathological conditions, such as chronic renal failure with renal mass reduction,lipopolysaccharide-induced renal dysfunction, and ischemic acute renal failure [20-22]. NO played an important role in renal vascular tone and hemodynamics[23]. Also, NO seems playing an ambiguous role during tissue I/R injury [24]. NO reduced leukocyte-induced injury by blocking leukocyte sequestration and activation. However, I/R also increased inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which potentiated injury [25], as produced NO reacted with oxygen radicals to form peroxynitrite [26]. Thus, NO seemed to have bidirectional effects on the pathogenesis of I/R induced acute renal failure, as suggested previously [27].

Various studies have indicated that NO biosynthesis and action were closely related to the pathogenesis of ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute renal failure (ARF) [28-30]. And previously,it was demonstrated that decreased endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation and NO production were related to an impaired renal function observed after I/R [31]. Further, the inhibition of NO synthase (NOS) was found to aggravate the postischemic ARF, thereby suggesting a renoprotective role of endogenous NO in this disease [29]. Moreover, the NO precursor L-arginine was reported to ameliorate postischemic ARF [32].

Therefore, it is of great clinical interest to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of renal I/R injury and to develop the suitable protective strategies.

The aim of the present study was to compare the protective effects of the nitric oxide donor, L-arginine, on renal ischemia reperfusion (I/R) injury with that of the antioxidant vitamin C in adult rats, as well as, the possible mechanisms of these effects. All experiments were performed in the Physiology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University.

Materials and methods

Animals

Animals used were 50 Wistar adult rats, of both sexes, weighing 150-200 grams.

Rats were purchased from the Research Inst itute of Ophthalmology, Giza, Egypt, and housed in animal cages (3 rats/cage) with suitable ventilation,temperature of 22-25°C, 12 hours light dark cycle and free access to food and water- ad libitum- in the Animal House, Physiology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Ain-Shams University. The animals allowed to the new environment for 7 days prior to experimental procedures to decrease the possible discomfort of animals.

Animals were not exposed to unnecessary pain or stress and animal manipulation was performed with maximal care and hygiene. Surgical procedure ran under anesthesia to avoid induction of pain in animals. At the end of experiment,animals were killed by overdose of anesthesia.Animal remains disposal occurred by incineration.

Animals were divided randomly into the following groups: Group I: Control group (10 rats), sham operated group. All animals in this group serve as control group and receive daily intraperitoneal(i.p) saline injections for 3 days, and then were subjected to the same procedure of Group II, but without Ischemia-Reperfusion (I/R). Group II: Renal I/R group (10 rats); received i.p injection of saline only for 3 days before I/R procedure. All animals in this group were subjected to I/R Procedure. At the day of sacrifice, animals were anaesthetized with Pentobarbital (40 mg/kg B.W., i.p.), abdominal midline incision was performed, and occlusion of the vascular pedicle of both kidneys was performed for 30 minutes [33], using microvascular atraumatic clamps. After 30 minutes, clamps were removed allowing reperfusion of renal tissues for another 30 minutes. Group III: L-arginine Pretreated renal I/R group (10 rats); all rats of this group were injected by L-arginine in a dose of 400 mg/kg/day i.p. for 3 days [34]. At the end of the 3 days, rats were exposed to Renal I/R. Group IV: Vitamin C Pretreated renal I/R group (10 rats); all rats of this group were injected by Vitamin C in a single dose of 500 mg/kg/day i.p. 24 hours [35] prior to I/R Procedure. Group V: Combined L-arginine and Vitamin C Pretreated renal I/R group (10 rats); all rats of this group were injected by L-arginine 400 mg/kg/day i.p. for 3 days and with a single dose of vitamin C 500 mg/kg/day i.p. 24 hours prior to I/R Procedure.

Collection of blood samples from abdominal aorta and excision of the left kidney for Nitric Oxide and oxidative stress markers were performed in all animals of the 5 studied groups. Also, right kidney was excised for histological examination.

Blood samples from the abdominal aorta were collected and the separated plasma was used for subsequent determination of plasma urea and plasma creatinine.

Kidney tissue was used for determination of the following:

(1) Markers of Oxidative stress; (2) Nitric Oxide; (3) Histological examination of the kidney.

Measurement of plasma urea and creatinine

Determination of plasma urea was performed according to the method described by Searcy et al. [36], using kits supplied by Biolabo, France. Plasma creatinine was estimated according to Jaffe reaction (kinetic method) described by Fabiny and Ertingshausen [37] and modified by Labbé et al. [38], using kits supplied by Biolabo, France.

Kidney tissue malondialdehyde level (MDA)

As a product of lipid peroxidation. Kidney tissues,stored frozen at -80°C till the day of MDA determination, were homogenized according to Eissa et al. [39], using the homogenizer Karl Kolb (scientific technical supplies D.6072, Dreieich, West Germany). The homogenization buffer (pH 7.2) consisted of 0.32 mmol/L Sucrose, 20 mmol/L N.2 hydroxyethyl piperazine N.2 ethane sulfonic acid (HEPES), 0.5 mmol/L Ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA), 1 mmol/L 1, 4 Dithio-DL-threitol (DTT), 1 mmol/L Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Sigma). One ml buffer was added for each 0.1 gm tissue. After homogenization, samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min., and MDA in the supernatant was determined according to the technique of Esterbauer and Cheeseman [40], in which MDA in the sample reacts with thiobarbituric acid in the reagent, and the produced colour read at wave length 535 nm. The obtained concentrations of MDA were then divided by 1000, the results being expressed in μmol/gm wet tissue.

Measurement of kidney tissue nitric oxide (NO)

The concentration of nitrate, a stable end-product of nitric oxide, was determined in homogenized kidney tissue samples according to the method described by Bories and Bories [41].

Kidney tissue catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD)

Catalase activity was measured based on the spectrophotometric method described by Aebi [42] using Bio-diagnostic kit (Cairo, Egypt). Superoxide dismutase activity was assayed on the basis of the ability of the enzyme to inhibit the phenazine methosulphatemediated reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium dye, producing a change in absorbance at 560 nm over 5 min [43], using Bio-diagnostic kit (Cairo, Egypt).

Histological examination of kidney

For detection of necrosis, infiltration, glomerular or tubular damage, small pieces of tissues were taken from the right kidney. Samples were fixed in 10% formalin for light microscopy. Paraffin embedded sections of 5-μm thickness were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for subsequent microscopic examination under high power.

Statistical analysis

All results in the present study were expressed as mean ± SE of the mean. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) program, version 20.0 was used to compare significance between each two groups. 1-Way ANOVA (Analysis Of Variance) for difference between means of different groups was performed on results obtained in the study. Differences was considered significant when p ≤ 0.05.

Ethics statement

This research project was submitted and approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University.

Results

Results of plasma urea and plasma creatinine

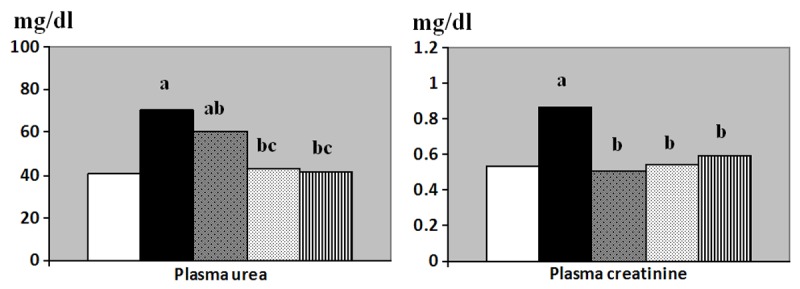

Results obtained from this study showed that; plasma urea (mg/dl) was significantly increased in the I/R group (70.8 ± 5.2) compared to the control group (40.2 ± 2.5, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, plasma urea was lowered in L-arginine pretreated group (60.4 ± 5.1, p < 0.01), vitamin C pretreated group (43.3 ±3.12, p < 0.001) and the combined treated group (41.7 ± 4.2, p < 0.001) compared to the I/R group. However, plasma urea was still significantly higher in the L-arginine pretreated group compared to control group. Also, plasma urea in the vitamin C pretreated and the combined treated groups was significantly lower than that of L-arginine pretreated group (p < 0.001 for both) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Plasma urea (mg/dl) and plasma creatinine (mg/dl) levels in control (Equation 1), I/R (Equation 2), L-arginine pre-treated (Equation 3), Vitamin C pre-treated (Equation 4) and combined treated (Equation 5) groups. a: Significance by LSD at P < 0.05 from control group. b: Significance by LSD at P < 0.05 from I/R group. c: Significance by LSD at P < 0.05 from L-arginine pre-treated I/R group.

Plasma creatinine level (mg/dl) was significantly increased in the I/R group (0.86 ± 0.06) compared to the control group (0.53 ± 0.06, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, plasma creatinine level was significantly decreased in L-arginine pretreated (0.51 ± 0.07), vitamin C pretreated (0.54 ± 0.05) and the combined treated group (0.59 ± 0.04) compared to the I/R group (p < 0.001, 0.001 and 0.01 respectively). No significant differences were detected between all of the treated groups and the control group (Figure 1).

Results of oxidative markers, antioxidant activity and nitric oxide

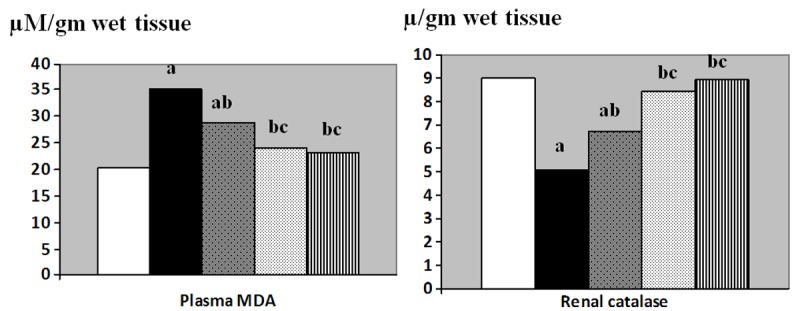

Kidney tissue MDA (μM/gm wet tissue) was significantly increased in the I/R group (35.1 ± 1.9) compared to the control group (20.2 ± 1.6, p < 0.001). Also, Kidney tissue MDA was significantly decreased in L-arginine pretreated group (28.7 ± 1.2), vitamin C pretreated group (24.1 ± 0.99) and the combined treated group (23.2 ± 1.8) compared to the I/R group (p < 0.01, 0.001 and 0.001 respectively). MDA in the L-arginine pretreated group was still significantly higher than that of control group. Moreover, significant decrease in MDA was detected in the vitamin C pretreated and in the combined treated groups when each was compared to the L-arginine pretreated group, p < 0.05 for both (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Renal malondialdehyde (MDA, μM/gm wet tissue) and renal catalase (μ/gm wet tissue) levels in control (Equation 1), I/R (Equation 2), L-arginine pre-treated (Equation 3), Vitamin C pre-treated (Equation 4) and combined treated (Equation 5) groups. a: Significance by LSD at P < 0.05 from control group. b: Significance by LSD at P < 0.05 from I/R group. c: Significance by LSD at P < 0.05 from L-arginine pre-treated I/R group.

Renal catalase (μ/gm wet tissue) was significantly decreased in the I/R group (5.09 ± 0.41) compared to the control group (8.98 ± 0.38, p < 0.001). Renal catalase was significantly increased in L-arginine pretreated (6.71 ± 0.41), vitamin C pretreated (8.39 ± 0.30) and in the combined treated (8.91 ± 0.26) groups when compared to the I/R group (p < 0.05, 0.001 and 0.001 respectively). Also, the values of the vitamin C pretreated and the combined treated groups were significantly higher than that of L-arginine pretreated group, p < 0.01 and 0.001 respectively. Renal catalase in the L-arginine pretreated was still significantly lower than that of control group, p < 0.05.

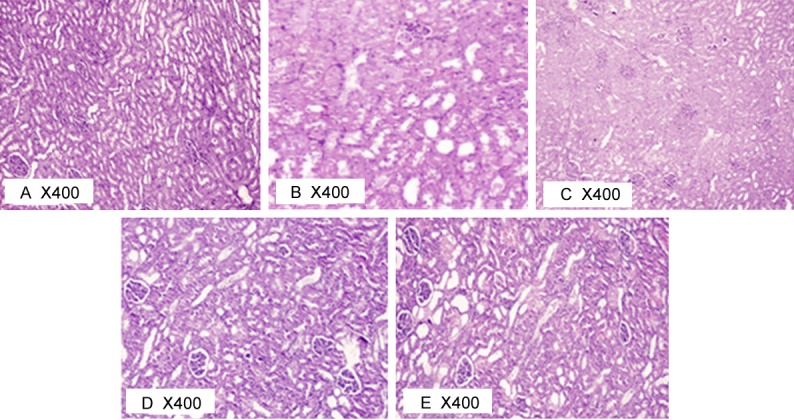

Although kidney tissue NO levels (μM/gm wet tissue) were lowered in I/R group, and higher in the L-arginine pretreated group, no significant changes in NO were detected between all the studied groups (Figure 2).

Similarly, no significant changes were detected in renal SOD (μ/gm wet tissue) amongst the studied groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kidney tissue nitric oxide (NO, μM/gm wet tissue) and renal superoxide dismutase (μ/gm wet tissue) levels in control (Equation 1), I/R (Equation 2), L-arginine pre-treated (Equation 3), Vitamin C pre-treated (Equation 4) and combined treated (Equation 5) groups. a: Significance by LSD at P < 0.05 from control group. b: Significance by LSD at P < 0.05 from I/R group. c: Significance by LSD at P < 0.05 from L-arginine pre-treated I/R group.

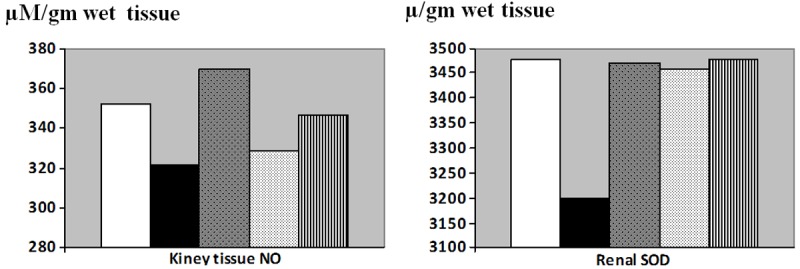

Results of histological examination of kidney tissue

H&E kidney stained sections (Figure 4) showed normal structure of the renal cortex and medulla of sham-operated control group (Figure 4A). This was markedly affected in renal I/R group (Figure 4B) with poor differentiation between renal cortex and medulla. The normal structure was somewhat regained in the L-arginine pre-treated group (Figure 4C), vitamin C pre-treated group (Figure 4D) and the combined treated group (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of rat kidney at 400X in different studied groups.

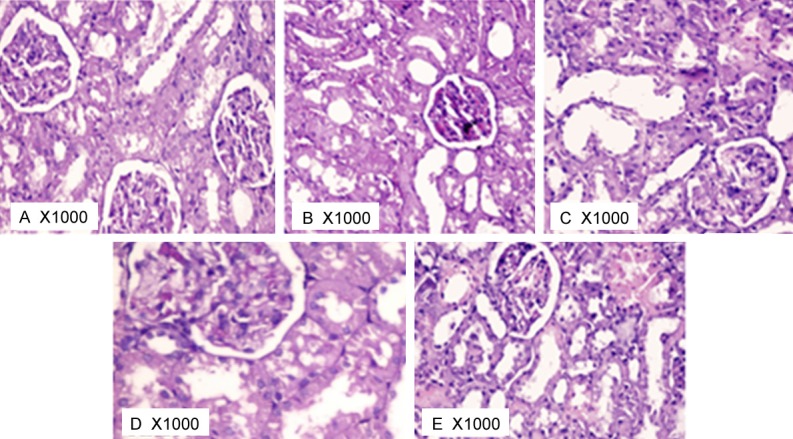

The renal corpuscles in different studied groups were demonstrated in Figure 5. In sham-operated control group (Figure 5A), the renal corpuscles were made up of tuft of convoluted capillaries (the glomerulus) enclosed inside the cup-shaped invagination of PCT (Bowman’s capsule, lined by squamous epithelium). The PCT revealed narrow lumen and were lined by cuboidal cells revealing spherical nuclei & eosinophilic cytoplasm. The DCT demonstrated lining cuboidal epithelium and had wider lumen. H&E kidney stained sections of I/R group (Figure 5B) revealed many evident histo-pathological changes. Regarding the glomeruli, asymmetrical shapes and sizes were seen. Other features of some glomeruli included; shrunken glomeruli, low cellularity, thickened parietal layer of Bowman’s capsule, and wide bowman’s space. H&E kidney stained sections of L-arginine pre-treated group (Figure 5C), vitamin C pre-treated group (Figure 5D) and the combined treated group (Figure 5E) showed remarkable regression of the histopathological changes caused by ischemia. Blood vessels looked normal with no dilatation or engorgement with blood. Glomeruli appeared apparently healthy in symmetry, size and cellularity.

Figure 5.

Photomicrograph of rat kidney glomeruli at 1000X in different studied groups.

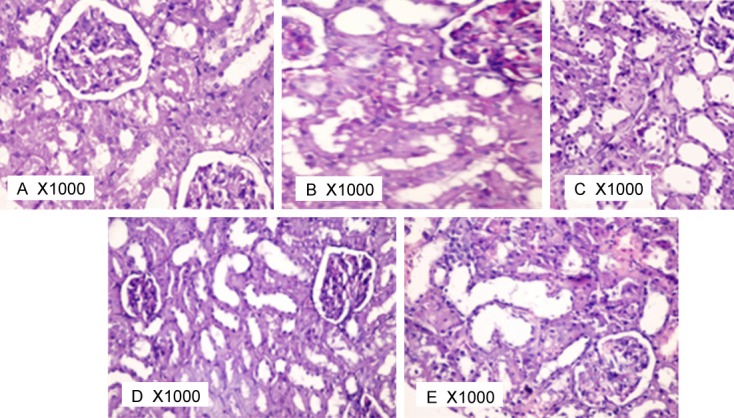

The renal tubules in different studied groups were demonstrated in Figure 6. In sham-operated group, the tubules were almost typically back to back with minimal interstitium in between. The medulla was occupied mostly by the collecting tubules that were lined by low columnar epithelium (Figure 6A). In I/R group (Figure 6B), epithelium lining tubules in some areas demonstrated signs of degeneration like vacuolation, swelling, pale frosted cytoplasm with normal nucleus. Other tubules showed necrotic changes of the epithelium with complete destruction of the epithelium. Widening of the interstitium was markedly evident and exhibited excessive number of inflammatory cell infiltration. Intra-renal arteries showed marked congestion with blood. The lumen of the tubules was widened and interstitium revealed dilated congested blood vessels.

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph of rat kidney tubules at 1000X in different studied groups.

Histopathological photomicrograph of L-argini-ne pre-treated group (Figure 6C), vitamin C pre-treated group (Figure 6D) and the combined treated group (Figure 6E) showed apparent regression of the tubular histopathological changes caused by ischemia. Most of the tubules appear healthy. However, still remain dispersed patches of tubular degeneration, necrosis, and hyaline cast deposition were seen.

It seemed that vitamin C pre-treated group (Figures 4D, 5D and 6D) showed more improvement for the renal tissue than in L-arginine pre-treated group (Figures 4C, 5C and 6C) and than in the combined treated group (Figures 4E, 5E and 6E) as less patches of kidney damage and less infiltration were noticed.

Discussion

The present study was performed to compare the protective effects of the antioxidant vitamin C with that of the nitric oxide donor, L-arginine, on renal ischemia reperfusion (I/R) injury in adult rats, as well as, the possible mechanisms of these effects.

The obtained results showed that plasma urea and creatinine levels were significantly increased in the I/R group compared to the control group. Meanwhile, plasma urea and creatinine levels were lowered in L-arginine pretreated group, vitamin C pretreated group and the combined treated group compared to the I/R group. Kidney tissue MDA was significantly increased in the I/R group compared to the control group, and was significantly decreased in L-arginine pretreated group, vitamin C pretreated group and the combined treated group compared to the I/R group. In the vitamin C pretreated and the combined treated groups plasma urea was significantly lowered in addition to significant decrease in MDA than that of L-arginine pretreated group.

Renal I/R injury caused a complex multifactor interaction between renal hemodynamics, in-flammatory mediators, endothelial and tubular injury. The kidney receives 25% of the cardiac output but the majority goes to the cortex and hence even slight changes in perfusion may lead to ischemia of the medulla [44]. During I/R injury renal endothelial and parenchymal cells secreted proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines[45]. The cytokines and the ROS produced by I/R injury upregulated the expression of adhesion molecules [46]. The combination of chemokines, cytokines and adhesion molecules lead to recruitment, activation and sequestration of leukocytes, which generated further ROS and cytokines and potentiated the injury [44].

Renal functions were impaired in the I/R group of the present study. The deteriorated renal functions were evidenced by elevated plasma urea and plasma creatinine levels. This is in accordance to the findings of many previous studies [4,6].

Increased oxidant stress in I/R group resulted in elevation of kidney tissue MDA, a good marker of oxidative stress. I/R rapidly promote the generation of superoxide and other ROS products such as hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical [47]. The early rise in ROS contributes to tissue damage and the loss of function in I/R-induced models of acute kidney injury [47].

Moreover, renal catalase activity was decreased after I/R in present study is in line with other previous studies that found a decrease in catalase activity [48,49] which could be due to the depressor effects of ROS generated during I/R on catalase gene expression [48].

Changes in kidney color during the process of I/R is a good confirmation of I/R in the present study. Moreover in the present study, the changes in renal histology in I/R group were obtained in the form of asymmetrical and shrunken glomeruli, vacuolation and swelling of epithelium lining convoluted tubules, necrotic changes of the epithelium lining tubules and excessive number of inflammatory cell infiltration of the interstitium. These findings clearly demonstrated the alteration in renal structure after I/R injury [2,50].

In the present study, pre-treatment with the antioxidant Vitamin C resulted in marked improvement in renal functions, manifested by significant decrease of plasma urea and creatinine levels and kidney MDA levels. These findings were similar to studies of Korkmaz and Kolankaya [51] and Vinodini et al. [52], and other previous studies that showed that the antioxidant ascorbic acid has been shown to attenuate renal damage caused by a variety of insults, such as postischemic stress, cisplatin, aminoglycosides, and potassium bromate in animals and had an extensive safety record as a dietary supplement in humans [13]. Also, improvements were noticed in Vitamin C pre-treated I/R group in the form of remarkable regression of the histopathological changes caused by ischemia. Glomeruli and tubules appeared apparently healthy and also most of the tubules, with less necrosis and infiltration.

Several mechanisms by which vitamin C may intervene in the oxidative-induced interaction between inflammatory cells and endothelial cells have been described. While P-selectin could be affected by aqueous-phase oxygen radicals, vitamin C might attenuate the up-regulation of this critical adhesion molecule by neutralizing these radicals [53]. Also, the water-soluble antioxidant intercepts aqueous-phase oxygen radicals before they attack lipoprotein lipids, thus also preventing the initiation of lipid peroxidation [53-55]. In Lloberas et al. [56], an I/R study, vitamin C reduced the production of PAF and PAF-like lipids, thus confirming that lipoperoxidation was affected and that was related to the suppression of aqueous-phase oxygen radical generation. Reducing the production of oxygen free radicals with an antioxidant could not only block enzymatic PAF synthesis,but could also prevent unregulated generation of circulating phospholipids with PAF activity, thus impeding subsequent oxidative events. So, reducing oxidative stress and subsequently the production of ROS by the antioxidant vitamin C in the present study is of great value in reducing renal structural and functional damage induced by I/R. This effect was evident by the decrease in renal tissue MDA, plasma urea and plasma creatinine, in addition to the less renal glomerulo-tubular and cellular damage in the vitamin C pretreated group. Moreover, vitamin C pretreatment resulted in an increase in plasma catalase activity after I/R. This could be attributed to the reduction of ROS and subsequently reduction of any depressor effect of ROS on gene expression of different enzymes [48].

L-arginine pretreated I/R group in the present study showed significantly reduced plasma ure-a, plasma creatinine levels and kidney MDA level, in addition to increase renal catalase activity. Also, improvements were noticed in the histopathological sections of kidneys in the L-arginine pre-treated group. These findings were in agreement with Garcia-Criado et al. [57], Nakajima et al. [58] and Tripatara et al. [59]. Garcia-Criado et al. [57] demonstrated that systemic treatment with a NO donor before reperfusion improved renal function and diminished inflammatory responses in a kidney subjected to an I/R process. Also, Tripatara et al. [59] demonstrated that topically administered sodium nitrite protects the rat kidney against I/R injury and dysfunction in vivo via the generation,in part, of xanthine oxidoreductase–catalyzed NO production. These observations suggested that nitrite therapy might prove beneficial in protecting kidney function and structural integrity during periods of I/R such as those encountered in renal transplantation. However, the effect of L-arginine in renoprotection was less marked than that of vitamin C as noticed in the higher plasma urea, renal MDA and lower renal catalase in the L-arginine pretreated group compared to control group, and also the less histopathological improvements. Meanwhile, Kidney tissue NO level, in the present study, was higher, although non-significant, in the L-arginine pretreated group but no significant changes in NO were detected between all the studied groups. Thus, the NO changes could play less role in renal IR injury than ROS generation mechanisms in this study.

It was found in the current study that pretreatment with L-arginine prior to I/R did not have better renoprotective effects when compared to other treated groups. That observation was somewhat similar to the previous study of Rhee et al. [60], who demonstrated that hepatic I/R increased the malondialdehyde level and exhausted the catalase activity remarkably. Vitamin C & vitamin E lowered the malondialdehyde levels and protected against catalase exhaustion, but had no significant effect on the NO production. L-arginine had a definite antioxidant effect, which was much weaker than that of Vitamin C & vitamin E.

However, a more recent study by Rusai et al. [61] in the ischemic rat kidney, observed that L-arginine (2 g/kg body weight daily) didn’t affect the injury sustained from I/R, but did increase the mRNA expression of NOS isoforms.This may be explained by time and dose administration differences between studies, along with the severity of the ischemic injury.

The minor role of L-arginine in the current study could be explained by the fact that NO has been shown to have several functions in the kidney, depending on its concentration, site of release, and duration of action [62]. For example,NO generated by inducible NO synthase (iNOS) has been shown to have cytotoxic effects on renal tubular epithelial cells [63]. In contrast, an increased expression of endothelial NOS (eNOS), which could lead to the enhanced production of endothelium-derived NO, might ameliorate ischemic and toxic renal injury by mediating vasodilation, inhibiting leukocyte adhesion, and reducing platelet aggregation[62]. They proposed the key role of endo thelial dysfunction in acute renal ischemia, suggesting that the defective production of endothelial NO might eventually lead to the destruction of tubular epithelial cells through vascular congestion or the “no reflow” phenomenon. Also, Nakajima et al. [58] demonstrated that, although preischemic treatment with a NO donor was renoprotective, postischemic treatment with the same agent aggravated the I/R induced renal injury, probably through peroxynitrite overproduction. It is postulated that under normal conditions, NO appears to protect renal function. However, this NO-dependent protection is lost during kidney failure, probably due to increased reactive oxygen species synthesis. The antioxidant treatment restores the viability of NO and prevents the tetrahydrobiopterin oxidation.Thus, this treatment may represent a therapeutic approach for the management of kidney disease [64].

The more apparent role of vitamin C observed in the current study when compared to NO donor was in agreement with Miloradović et al. [65] who demonstrated that L-arginine failed to reduce tubular injury, despite its evident improvement of systemic and renal hemodynamic,thus NO seemed to act as a double-egged sword, but reduction of tubular injury promoted vitamin C as an effective chemoprotectant against I/R tubular injury in hypertension.

However, the more apparent effect of vitamin C than L-arginine found in the present study was in disagreement to Unal et al. [66], who found that the exogenous nitric oxide (Na-nitroprusside) inhibited xanthine oxidase, and had more apparent preventive features for renal I/R injury than the antioxidant vitamins C+E. But that improving vitamin C effect was in line with the study of Mahfoudh-Boussaid et al. [67], who showed that ischemia preconditioning and vitamin C improved the functional parameters of ischemic testis. However, the protective effects are attenuated when the two treatments are combined. They also demonstrated that a potent antioxidant like vitamin C was found to be more effective than increasing blood flow by a vasodilator like dopamine on improving I/R injury following testicular ischemia.

The current study showed no significant changes detected in renal SOD amongst the studied groups despite of significant improvement in renal function in the different treated group. Previous studies about the effect of renal I/R on SOD were controversial. Rasoulian et al. [49] found an increase in renal SOD activity after I/R, while Chander and Chopra [68] found that renal SOD activity decreased following 45 min ischemia and 24 h reperfusion. Moreover, Erdogan et al. [69] detected increased renal SOD activity after 30 min ischemia and 120 min reperfusion although this increase was not significant. It could be concluded from these studies that the effect of renal I/R on SOD depends on the duration of I/R process and on the part of kidney taken for estimation of SOD activity, since most of kidney SOD activity is related to renal cortex [70].

Thus, the oxidant stress represents the most important factor underlying I/R renal damage. It is therefore of much value to minimize the oxidative stress and reduce the production of ROS to protect kidneys from deleterious effects in structure and function. The role of NO in protecting against or in promoting I/R renal injury should be studied further.

Conclusion

Renal I/R injury resulted in marked oxidative stress to renal tissue that leads to deterioration in renal functions, increased urea, creatinine, MDA, and decrease catalase activity, in addition to evident pathological changes in renal structure. Treatment with the NO donor L-arginine or with the antioxidant vitamin C before renal I/R could partially protect against I/R injury evidenced by the decrease in plasma urea and creatinine, in addition to the decrease in renal MDA and the increase in renal catalase,and amelioration of the pathological changes in kidney structure. The reno-protective effects of pretreatment with vitamin C were significantly more apparent than the pretreatment with L-arginine. Combined pretreatment with both L-arginine and vitamin C did not produce more protective effects than vitamin C alone.

Thus, it could be concluded that oxidative stress is the primary element involved in renal I/R injury. So, antioxidants could play an important role than NO donors in amelioration of renal I/R injury.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Star RA. Treatment of acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1817–1831. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ko GJ, Boo C, Jo S, Cho WY, Kim HK. Macrophages contribute to the development of renal fibrosis following ischaemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:842–852. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basile DP. The endothelial cell in ischemic acute kidney injury: implications for acute and chronic function. Kidney Int. 2007;72:151–156. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim J, Jang H, Park KM. Reactive oxygen species generated by renal ischemia and reperfusion trigger protection against subsequent renal ischemia and reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F158–F166. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00474.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venkatachalam MA, Griffin KA, Lan R, Geng H, Saikumar P, Bidani AK. Acute kidney injury: a springboard for progression in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F1078–F1094. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00017.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basile DP, Leonard EC, Tonade D, Friedrich JL, Goenka S. Distinct effects on long-term function of injured and contralateral kidneys following unilateral renal ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F625–F635. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00562.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basile DP, Leonard EC, Beal AG, Schleuter D, Friedrich J. Persistent oxidative stress following renal ischemia-reperfusion injury increases ANG II hemodynamic and fibrotic activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F1494–F1502. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00691.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nath K, Norby S. Reactive oxygen species and acute renal failure. Am J Med. 2000;109:665–678. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00612-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nordberg J et al. Reactive oxygen species,antioxidants, and the mammalian thioredoxin system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1287–1312. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobashi K, Ghosh B, Orak JK, Singh I, Singh AK. Kidney ischemia-reperfusion: Modulation of antioxidant defenses. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;205:1–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1007047505107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Padanilam BJ. Cell death induced by acute renal injury: a perspective on the contributions of apoptosis and necrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F608–F627. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00284.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spargias K, Alexopoulos E, Kyrzopoulos S, Iokovis P, Greenwood DC, Manginas A, Voudris V, Pavlides G, Buller CE. Kremastinos D and Cokkinos DV. Ascorbic acid prevents contrast-mediated nephropathy in patients with renal dysfunction undergoing coronary angiography or intervention. Circulation. 2004;110:2837–2842. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146396.19081.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J, Kil IS, Seok YM, Yang ES, Kim DK, Lim DG, Park JW, Bonventre JV, Park KM. Orchiectomy attenuates post-ischemic oxidative stress and ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. A role for manganese superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20349–20356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niki E. Action of ascorbic acid as a scavenger of active and stable oxygen radicals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:1119S–1124S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.6.1119s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antunes LM, Darin JD, Bianchi MD. Protective effects of vitamin C against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and lipid peroxidation in adult rats: a dose-dependent study. Pharmacol Res. 2000;41:405–411. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ocak S, Gorur S, Hakverdi S, Celik S, Erdogan S. Protective effects of caffeic acid phe-nethyl ester, vitamin C, vitamin E and N-acetylcysteine on vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;100:328–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kone BC, Baylis C. Biosynthesis and homeostatic roles of nitric oxide in the normal kidney. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:F561–F578. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.5.F561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majid DSA, Navar LG. nitric oxide in the control of renal hemodynamics and excretory function. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:74S–82S. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashab I, Peer G, Blum M, Wollman Y, Chernihovsky T, Hassner A, Schwartz D, Cabili S, Silverberg D, Iaina A. Oral administration of L-arginine and captopril in rats prevents chronic renal failure by Nitric oxide production. Kidney Int. 1995;47:1515–1521. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caramelo C, Espinosa G, Manzarbeitia F, Cernadas MR, Pérez Tejerizo G, Tan D, Mosquera JR, Digiuni E, Montón M, Millás I, Hernando L, Casado S, López-Farré A. Role of endotheliumrelated mechanisms in the pathophysiology of renal ischemia/reperfusion in normal rabbits. Circ Res. 1996;79:1031–1038. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.5.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz D, Mendonca M, Schwartz I, Xia Y, Satriano J, Wilson CB, Blantz RC. Inhibition of constitutive nitric oxide synthase (NOS) by nitric oxide generated by inducible NOS after lipopolysaccharide administration provokes renal dysfunction in rats. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:439–448. doi: 10.1172/JCI119551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabbai FB, Blantz RC. Role of nitric oxide in renal hemodynamics. Semin Nephrol. 1999;19:242–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhoden EL, Rhoden CR, Lucas ML, Pereira-Lima L, Zettler C, Belló-Klein A. The role of nitric oxide pathway in the renal ischemia–reperfusion injury in rats. Transplant Immunology. 2002;10:277–284. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(02)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatterjee PK, Patel NS, Kvale EO, Cuzzocrea S, Brown PA, Stewart KN, Mota-Filipe H, Thiemermann C. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase reduces renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 2002;61:862–871. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker LM, Walker PD, Imam SZ, Ali SF, Mayeux PR. Evidence for peroxynitrite formation in renal ischemia–reperfusion injury: studies with the inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-N (6)-(1-Iminoethyl) lysine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:417–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goligorsky MS, Noiri E. Duality of nitric oxide in acute renal failure. Semin Nephrol. 1999;19:263–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conger JD, Robinette JB, Hammond WS. Differences in vascular reactivity in models of ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 1991;39:1087–1097. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chintala MS, Chiu PJS, Vemulapalli S, Watkins RW, Sybertz EJ. Inhibition of endothelial derived relaxing factor (EDRF) aggravates ischemic acute renal failure in anesthetized rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1993;348:305–310. doi: 10.1007/BF00169160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pryor WA, Squadrito GL. The chemistry of peroxynitrite: a product from the reaction of nitric oxide with superoxide. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L699–L722. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.5.L699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conger JD, Robinette JB, Schrier RW. Smooth muscle calcium and endothelium-derived relaxing factor in the abnormal vascular responses of acute renal failure. J Clin Investig. 1988;82:532–537. doi: 10.1172/JCI113628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schramm L, Heidbreder E, Schmitt A, Kartenbender K, Zimmermann J, Ling H, Heidland A. Role of L-arginine-derived NO in ischemic acute renal failure in the rat. Renal Failure. 1994;16:555–569. doi: 10.3109/08860229409044885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly KJ. Distant Effects of Experimental Renal Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1549–1558. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000064946.94590.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Acquaviva R, Lanteri R, Li Destri G, Caltabiano R, Vanella L, Lanzafame S, Di Cataldo A, Li Volti G, Di Giacomo C. Beneficial effects of rutin and L-arginine coadministration in a rat model of liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G664–G670. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90609.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanter M, Coskun O, Armutcu F, Uz YH, Kizilay G. Protective Effects of Vitamin C, Alone or in Combination with Vitamin A, on Endotoxin-Induced Oxidative Renal Tissue Damage in Rats. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005;206:155–162. doi: 10.1620/tjem.206.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Searcy RL, Reardon JE, Foreman JA. A new photometric method for serum urea nitrogen determination. Am J Med Technol. 1967;33:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fabiny DL, Ertingshausen G. Automated Reaction-Rate Method for determination of serum creatinine with the centrifichem. Clinical Chem. 1971;17:696–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Labbé D, Vassault A, Cherruau B, Baltassat P, Bonète R, Carroger G, Costantini A, Guérin S, Houot O, Lacour B, Nicolas A, Thioulouse E, Trépo D. Method selected for the determination of creatinine in plasma or serum. Choice of optimal conditions of measurement. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 1996;54:285–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eissa S, Khalifa A, El-Ahmady O. Tumor markers in malignant and benign breast tissue CA15.3, CEA and ferritin in cytosol and membrane enriched fractions. J Tumor Marker Oncol. 1990;5:220. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Esterbauer H, Cheeseman KH. Determination of aldehydic lipid peroxidation products: malonaldehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:407–421. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86134-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bories PN, Bories C. Nitrate determination in biological fluids by an enzymatic one-step assay with nitrate reductase. Clinical Chemistry. 1995;41:904–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishikimi M, Appaji N, Yagi K. The occurrence of superoxide anion in the reaction of reduced phenazine methosulfate and molecular oxygen. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1972;46:849. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(72)80218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kher A, Meldrum KK, Wang M, Tsai BM, Pitcher JM, Meldrum DR. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of sex differences in renal ischemia–reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonventre JV, Zuk A. Ischemic acute renal failure: an inflammatory disease? Kidney Int. 2004;66:480–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.761_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ysebaert DK, De Greef KE, De Beuf A, Van Rompay AR, Vercauteren S, Persy VP, De Broe ME. T cells as mediators in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 2004;66:491–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.761_4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fekete A, Vannay A, Ver A, Vasarhelyi B, Muller V, Ouyang N, Reusz G, Tulassay T, Szabo AJ. Sex differences in the alterations of Na(+), K(+)-ATPase following ischaemia–reperfusion injury in the rat kidney. J Physiol. 2004;555:471–480. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.054825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh D, Chander V, Chopra K. Protective effect of catechin on ischemia-reperfusion-induced renal injury in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rasoulian B, Jafari M, Noroozzadeh A, Mehrani H, Wahhab-Aghai H, Hashemi-Madani SMH, Ghani E, Esmaili M, Asgar A, Khoshbaten A. Effects of ischemia-reperfusion on rat renal tissue antioxidant systems and lipid peroxidation. Acta Medica Iranica. 2008;46:353–360. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamasowa H, Shimizu S, Inoue T, Takaoka M, Matsumura Y. Endothelial nitric oxide contributes to the renal protective effects of ischemic preconditioning. JPET. 2005;312:153–159. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.074427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korkmaz A, Kolankaya D. The Protective Effects of Ascorbic Acid against Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Male Rats. Renal Failure. 2009;31:36–43. doi: 10.1080/08860220802546271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vinodini NA, Tripathi Y, Raghuveer CV, Ranade A, Kamath A, Pai S. Effect of antioxidants (vitamin C) on tissue ceruloplasmin following renal ischemia reperfusion in Wistar rats. International Journal of Biomedical and Advance Research. 2012;3:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patel KD, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM, McEver RP, McIntyre TM. Oxygen radicals induce human endothelial cells to express GMP-140 and bind neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:749–759. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frei B, Forte TM, Ames BN, Cross CE. Gas phase oxidants of cigarette smoke induce lipid peroxidation and changes in lipoprotein properties in human blood plasma. Protective effects of ascorbic acid. Biochem J. 1991;277:133–138. doi: 10.1042/bj2770133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lehr HA, Frei B, Afors KE. Vitamin C prevents cigarette smoke-induced leukocyte aggregation and adhesion to endothelium in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7688–7692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lloberas N, Torras J, Herrero-Fresneda I, Cruzado JM, Riera M, Hurtado I, Griny JM. Postischemic renal oxidative stress induces inflammatory response through PAF and oxidized phospholipids. Prevention by antioxidant treatment. FASEB J. 2002;16:908–910. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0880fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garcia-Criado FJ, Eleno N, Santos-Benito F, Valdunciel JJ, Reverte M, Lozano-Sánchez FS, Ludeña MD, Gomez-Alonso A, López-Novoa JM. Protective effect of exogenous Nitric Oxide on the renal function and inflammatory response in a model of ischemia-reperfusion. Transplantation. 1998;66:982–990. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810270-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakajima A, Ueda K, Takaoka M, Yoshimi Y, Matsumura Y. Opposite Effects of Pre- and Postischemic Treatments with Nitric Oxide Donor on Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced Renal Injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:1038–1046. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tripatara P, Patel NSA, Webb A, Rathod K, Lecomte FMJ, Mazzon E, Cuzzocrea S, Yaqoob MM, Ahluwalia A, Thiemermann C. Nitrite-Derived Nitric Oxide Protects the Rat Kidney against Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury In Vivo: Role for Xanthine Oxidoreductase. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:570–580. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rhee JE, Jung SE, Shin SD, Suh GJ, Noh DY, Youn YK, Oh SK, Choe KJ. The effects of antioxidants and nitric oxide modulators on hepatic ischemic-reperfusion injury in rats. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:502–506. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.4.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rusai K, Fekete A, Szebeni B, Vannay A, Bokodi G, Müller V, Viklicky O, Bloudickova S, Rajnoch J, Heemann U, Reusz G, Szabó A, Tulassay T, Szabó AJ. Effect of inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase and L-arginine supplementation on renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and the renal nitric oxide system. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:1183–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.04976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goligorsky MS, Brodsky SV, Noiri E. Nitric oxide in acute renal failure: NOS versus NOS. Kidney Int. 2002;61:855–861. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Noiri E, Peresieni T, Miller F, Goligorsky MS. In vivo targeting of inducible NO synthase with oligodeoxynucleotides protects rat kidney against ischemia. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2377–2383. doi: 10.1172/JCI118681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arellano-Mendoza MG, Vargas-Robles H, Del Valle-Mondragon L, Rios A, Escalante B. Prevention of renal injury and endothelial dysfunction by chronic L-Arginine and antioxidant treatment. Ren Fail. 2011;33:47–53. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.541583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miloradović Z, Mihailović-Stanojević N, Grujić-Milanović J, Ivanov M, Kuburović G, Marković-Lipkovski J, Jovović D. Comparative effects of L-arginine and vitamin C pretreatment in SHR with induced postischemic acute renal failure. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2009;28:105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Unal D, Yeni E, Erel O, Bitiren M, Vural H. Antioxidative effects of exogenous nitric oxide versus antioxidant vitamins on renal ischemia reperfusion injury. Urol Res. 2002;30:190–194. doi: 10.1007/s00240-002-0254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mahfoudh-Boussaid A, Badet L, Zaouali A, Saidane-Mosbahi D, Miled A, Ben Abdennebi H. Effect of ischaemic preconditioning and vitamin C on functional recovery of ischaemic kidneys. Prog Urol. 2007;17:836–840. doi: 10.1016/s1166-7087(07)92303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chander V, Chopra K. Protective effect of nitric oxide pathway in resveratrol renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Erdogan H, Fadillioglu E, Yagmurca M, Uçar M, Irmak MK. Protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation after renal ischemia-reperfusion injury: protective effects of erdosteine and N-acetylcysteine. Urol Res. 2006;34:41–46. doi: 10.1007/s00240-005-0031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gonzalez-Flecha B, Evelson P, Sterin-Speziale N, Boveris A. Hydrogen peroxide metabolism and oxidative stress in cortical, medullary and papillary zones of rat kidney. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1157:155–161. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(93)90059-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]