Abstract

More than 60% of the total area of tree plantations in China is in subtropical, and over 70% of subtropical plantations consist of pure stands of coniferous species. Because of the poor ecosystem services provided by pure coniferous plantations and the ecological instability of these stands, a movement is under way to promote indigenous broadleaf plantation cultivation as a promising alternative. However, little is known about the carbon (C) stocks in indigenous broadleaf plantations and their dependence on stand age. Thus, we studied above- and below-ground biomass and C stocks in a chronosequence of Mytilaria laosensis plantations in subtropical China; stands were 7, 10, 18, 23, 29 and 33 years old. Our assessments included tree, shrub, herb and litter layers. We used plot-level inventories and destructive tree sampling to determine vegetation C stocks. We also measured soil C stocks by analyses of soil profiles to 100 cm depth. C stocks in the tree layer dominated the above-ground ecosystem C pool across the chronosequence. C stocks increased with age from 7 to 29 years and plateaued thereafter due to a reduction in tree growth rates. Minor C stocks were found in the shrub and herb layers of all six plantations and their temporal fluctuations were relatively small. C stocks in the litter and soil layers increased with stand age. Total above-ground ecosystem C also increased with stand age. Most increases in C stocks in below-ground and total ecosystems were attributable to increases in soil C content and tree biomass. Therefore, considerations of C sequestration potential in indigenous broadleaf plantations must take stand age into account.

Introduction

Biomass and carbon (C) stocks in forest ecosystems play important roles in the global C cycle [1], [2], [3], [4]. Trees and soils are components of forest ecosystems that provide the largest potential for C storage [3], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Increasing global C sequestration through enlargement of the proportion of forested land on the planet has been suggested as an effective measure for mitigating elevated concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide [10], [11], [12]. As the area of natural stands has decreased in recent decades, tree plantations have become increasingly important components of the planet's forest resources. Commercial plantations are now a central issue in sustainable forest management across the globe. Well-designed, multi-purpose plantations can reduce pressure on natural forests, restore some ecological services provided by natural forests and mitigate climate change through direct C sequestration [13].

China's large plantation programme is assuming an increasingly significant role in C sequestration from the atmosphere. The total land area under tree plantations has reached 6.2×107 ha and now accounts for 31.8% of the total forested landscape in the country [14]. The largest proportion (63%) of the total plantation area in China is located in subtropical regions, which provide hot and humid conditions appropriate for tree growth [15]. Most of these subtropical plantations consist of stands containing either a single coniferous species or an exotic tree (e.g. Pinus massoniana, Cunninghamia lanceolata, Eucalyptus) [15]. The creation of monospecific stands of trees that are not native to a landscape carries a high risk of consequential ecological damage, such as decrease in ecosystem stability and outbreak of diseases and insect pests [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. As a result, alternative plantations of indigenous broadleaf species are spreading in this region of China and in neighbouring countries [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27].

Mytilaria laosensis, an indigenous broadleaf tree species, has potential in the afforestation of subtropical China. It grows rapidly and is strongly adaptable; the trunk is straight and the wood has desirable properties for the economic production of high-value timber. The species occurs naturally in western Guangdong, south-western Guangxi and south-eastern Yunnan. It is also indigenous to Vietnam and Laos. M. laosensis is expected to become a major afforestation species in subtropical China and beyond [28], [29], [30]. Its growth patterns, biomass production and wood properties, and the physical and chemical properties of the soils in which it grows have been reported in earlier literature [28], [31], [32], [33]. However, information on biomass and C stocks in M. laosensis stands is still lacking. According to previous investigations, C stock size in plantations (especially biomass C) is related not only to tree species, site conditions and soil properties [34], [35], [36], but also to stand age. According to the previous studies, the C stock of Castanopsis hystrix plantations and Erythrophleum fordii plantation in subtropical China were increased with the increase in stand age [38], [39]. And in the other region, stand age can also remarkably affect the C stocks of plantations' ecosystem [10], [37]. However, Effects of diverse factors, including stand age, on C sequestration by M. laosensis plantation are poorly documented [33].

Here, we provide first measurements of the C stock across an age sequence of six M. laosensis plantation stands. Specifically, the objectives of this study were (1) to document the changes of the sizes and proportional contributions of plantation C pools as stands aged in the early decades following plantation establishment, and (2) to provide baseline information for forest biomass and C estimations focussing on indigenous broadleaf plantations in subtropical regions.

Materials and Methods

Study site and plot establishment

Ethics statement

This research was conducted in Experimental Center of Tropical Forestry, Chinese Academy of Forestry (ECTF for short), This study was also supported by this center. We confirmed that the location is not privately owned and the sampling of soils and plants was approved by ECTF. We also confirmed that the field studies did not involve endangered or protected species.

Study site

The study site is located in the Experimental Centre of Tropical Forestry at the Chinese Academy of Forestry location in Pingxiang City, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China (22°02′–22°19′N, 106°43′–106°52′E). The region is within a semi-humid southern subtropical monsoon climate zone that has defined dry and wet seasons. The dry season extends from October to the following March, and the wet season from April to September. The annual mean precipitation at the site is 1200–1500 mm, annual average evaporation is 1261–1388 mm and the relative humidity is 80–84%. The annual mean temperature is 21°C, with a mean monthly minimum of 12.1°C and a mean monthly maximum of 26.3°C. The landscape is largely comprised of low mountains and hills at elevations of 350–650 m. The soils at the study site are categorised as red soils by the Chinese soil classification procedure; this category is equivalent to Oxisol in the USDA Soil Taxonomy. Most developed from granite and had a sandy texture [40], [41], [42].

Plot establishment

In 2013,six adjacent plantations with different stand ages were selected based on similarities in topography, soil texture, management methodology, environmental conditions and previous vegetation composition (dominated by C. lanceolata). We identified a chronosequence of M. laosensis stands that were 7, 10, 18, 23, 29 and 33 years of age. All six stands were located within 15 km of one another. They were established in 2006, 2003, 1995, 1990, 1984 and 1980, after the clear-cutting of previous C. lanceolata vegetation. Stand characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Site properties and vegetation characteristics of the six plantation stands studied (values are means ±SE; n = 4).

| 7 yr old | 10 yr old | 18 yr old | 23 yr old | 29 yr old | 33 yr old | |

| Altitude (m) | 360–520 | 450–530 | 450–540 | 550–650 | 450–550 | 350–500 |

| Slope aspect | North-western | Northern | North-western | Northern | Northern | North-western |

| Slope gradient (°) | 36.1±2.4 | 37.7±3.1 | 34.2±1.8 | 32.2±2.2 | 32.8±2.6 | 28.9±1.7 |

| DBH (cm) | 13.6±0.7 | 16.2±1.2 | 20.2±1.2 | 23.4±1.7 | 26.0±2.3 | 27.3±2.7 |

| Tree height (m) | 13.6±1.4 | 14.9±1.1 | 16.1±1.7 | 17.8±2.7 | 21.9±3.1 | 20.5±1.9 |

| Stem density (trees ha−1) | 1500±21 | 1224±18 | 911±12 | 721±11 | 675±8 | 671±10 |

| Main understorey species | M. laosensis, Cunninghamia lanceolata | M. laosensis, Thysanolaena maxima | M. laosensi, T. maxima | M. laosensis, C. lanceolata | M. laosensis, C. lanceolata | M. laosensis, T. maxima |

During the summer of 2013, four sampling plots (each 30×20 m) were established at random locations in each of the six stands. In each of these plots, we measured the diameter at breast height (DBH, diameter at breast height) of individual trees using a diameter tape, and measured heights using a Hag-löf-VERTEX IV clinometer. Five subplots containing shrubs (each 2×2 m) and five subplots of herbaceous vegetation and litter (each 1×1 m) were established at random locations within each sampling plot (20 subplots in total in the stands of the same age). Plant species, numbers, heights and coverages were recorded; litter was collected from litter subplots (each 1×1 m). Environmental factors including altitude, slope, aspect and slope position were also recorded.

Measurements

Tree biomass

On the basis of the DBH and height measurements in the sampling plots, we selected and harvested six sample trees from different diameter classes in each of the six stands for biomass measurements (36 trees in total). The above-ground portions of the trees were divided into 2-cm sections for measurement. We measured the fresh weights of stems, bark, branches and leaves. The below-ground portions of the sample trees were dug out and examined using the open cut method. We measured the fresh weights of the stump roots, thick roots (diameter >2.0 cm), medium-thick roots (diameter 0.5–2.0 cm) and small roots (diameter <0.5 cm). Organ samples were collected (200 g of each organ) and oven-dried at a temperature of 65°C to constant weight to calculate the moisture contents and dry weights. We built regression models for the different organs to estimate tree biomass (using data from the 18 sample trees).

Understorey vegetation and litter biomass

We used a destructive harvesting method to measure the biomass in the above-ground and below-ground portions of the shrub and herbaceous layers [43]. The fresh masses of these two portions were obtained directly by weighing. After oven-drying to constant weight at 65°C, we weighed subsamples and calculated the respective dry weights from determinations of moisture contents. The components of understorey vegetation were then separated and measured. We weighed litter material that had not decomposed or was semi-decomposed at the same time. The litter samples were oven dried at 65°C and weighed.

C content

Samples of the above-ground and below-ground components of the sample trees (M. laosensis), shrubs, herbaceous plants and litter were dried, ground and sieved in the laboratory. These samples were then bottled for later chemical analysis. In total, 288 soil-sampling points were selected within the 24 sampling plots in each of the six stands. Soil pits were dug to a depth of 100 cm and samples were collected randomly from four depth horizons: 0–10 cm, 10–30 cm, 30–50 cm and 50–100 cm. Soil samples from the same depth horizon in the same stand were mixed in equal proportions and the mixtures were air-dried at room temperature (25°C). The samples were then ground and passed through a 2-mm-mesh sieve to remove coarse living roots and gravel; they were then ground in a mill in preparation for sieving through a 0.25-mm mesh before chemical analysis. A soil-sample cutting ring (100 cm3) was used to collect samples of undisturbed soil from different horizons. These samples were taken to the laboratory for measurements of soil bulk density using the cutting ring method. We measured the C content of the tree component samples, understorey vegetation, litter by vario Macro Elemental Analyzer (Elementar Analyasensysteme GmbH, Germany), but the soil organic carbon was established by the oil-bath K2Cr2O7 titration method.

C storage

The C stocks (C in biomass per unit area of land surface) in the vegetation and litter biomass were determined by multiplying C content by biomass (dry mass per unit area of land surface). The C stocks per unit area of land in each of the soil horizons were calculated by multiplying soil bulk density at a chosen soil depth by the C content at that depth. Total soil C stocks were computed by summing the stocks in each soil horizon.

Statistical analysis

We used one-way ANOVA to test for differences in the C content and C stock among plantations of different ages. The dependent parameters were normally distributed and homoscedastic. All analyses were performed using the following software: Microsoft Excel 2007 and SPSS (ver.13.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL) for Windows. Statistical significance was detected at P<0.05.

Results

C content in plantation stands

C content in the vegetation and litter layer

The C contents of the component organs differed significantly among the six stands (P<0.05) and fell into the following rank order: leaf > stem > coarse root > medial root > bark > small root > branch > stump root > fruit. C content was not significantly different between medium roots and bark (P<0.05). The C contents of above-ground components of the shrub and herb layers in all six stands were higher than those of their below-ground components. In the litter layer, the C content of the undecomposed portion was higher than that of the semi-decomposed portion (Table 2).

Table 2. Carbon contents in the vegetation components and litter layers of six differently aged plantation stands (values are means ±SE; n = 4 g kg−1).

| Layer | Components | 7 yr old | 10 yr old | 18 yr old | 23 yr old | 29 yr old | 33 yr old | Mean |

| Tree layer | Stem | 527.8±14.1Eb | 536.9±12.7Cb | 545.6±16.4Bab | 520.7±29.3Cb | 556.7±15.2Ba | 569.1±34.7ABa | 542.8±20.4Cb |

| Bark | 524.4±11.6Fa | 534.8±31.2Ca | 554.1 ±24.8ABa | 506.8±13.7Da | 543.2±19.4Ca | 517.9±18.8Da | 530.2±22.3Da | |

| Branches | 534.1±27.6Da | 512.5±21.8Ea | 532.2±31.5Ca | 498.8±33.2Eb | 516.9±19.7Ea | 542.3 ±41.2Ba | 522.8±28.6Ea | |

| Leaves | 573.6±44.7Aa | 525.9 ±31.2Ca | 547.1±28.8Ba | 560.2±42.9Aa | 568.3±44.4Aa | 586.1±36.1Aa | 560.2±38.4Aa | |

| Fruit | 512.4±17.2Ha | 498.8 ±21.8Fa | 505.2±15.4Ea | 489.7±17.7Fa | 504.3±21.9Fa | 488.4±20.4Ea | 499.8±18.8Ha | |

| Stump roots | 514.3±22.2Ga | 533.7±27.4Ca | 498.2±23.7Fb | 509.6±14.9Dab | 532.1±20.8Da | 508.1±24.6DEa | 516.0±23.8Fa | |

| Coarse roots | 543.4±31.8Ca | 554.1±37.1Aa | 527.6±30.4Ca | 538.7±28.6Bab | 520.8±27.3Eb | 558.4±40.2Ba | 540.5±33.6Cab | |

| Medium roots | 517.9±30.2Fa | 541.7±37.7Ba | 532.8±24.9Ca | 557.4±40.2Aa | 531.0±23.4Da | 520.2±28.7Ca | 533.5±32.6Da | |

| Small roots | 544.1±23.8Ca | 537.0 ±31.9BCa | 515.6±21.3Da | 520.4±19.4Ca | 536.3±33.1CDa | 525.4±29.2Ca | 529.8±25.2Da | |

| Average of roots | 529.9±26.8Ea | 541.6±34.2Ba | 518.6±21.7Da | 531.5±23.7BCa | 530.1±27.4Da | 533.7±28.9Ca | 530.9±28.3Da | |

| Average of trees | 538.0±25.5Da | 530.3±30.4Ca | 539.5±27.1BCa | 523.6±34.2Ca | 543.0±27.3Ca | 549.9 ±26.5Ba | 537.4±29.7CDa | |

| Shrub layer | Above ground | 544.2±32.2Ca | 516.7±21.7Da | 545.2±31.8Ba | 534.8±25.5Ba | 541.7±27.4Ca | 522.2±18.9Ca | 534.1±25.8Da |

| Below ground | 522.3±17.3Fa | 522.4 ±19.1CDa | 497.5±20.4Fa | 508.4±24.3Da | 516.8±19.4Ea | 519.2±9.7CDa | 514.4±18.3FGa | |

| Average | 533.3±28.3Da | 519.6±19.6Da | 521.4±25.3Ca | 521.6±14.8Ca | 529.3±25.4Da | 520.7±13.7Ca | 524.3±22.9DEa | |

| Herb layer | Above ground | 513.3±31.7Ha | 532.8±28.8Ca | 527.9±35.4Ca | 508.4±31.0Da | 529.1±19.8Da | 511.7±27.6Da | 520.5±30.7Ea |

| Below ground | 518.4±27.2Fa | 509.3±19.7Ea | 497.6±16.9Fa | 509.8±21.3Da | 524.2±24.7DEa | 510.5±18.8Da | 511.6±20.6Ga | |

| Average | 515.9±29.7Ga | 521.05 ±25.4Da | 512.8±27.3Ea | 509.1±26.8Da | 526.7±22.3Da | 511.1±25.2Da | 516.1±26.4Fa | |

| Litter layer | Undecomposed | 557.8±32.2Ba | 578.4±40.4Aa | 562.1±34.2Aa | 550.9±27.9ABa | 564.2±40.1Aa | 578.5±31.2Aa | 565.3±35.7A |

| Semi-decomposed | 554.2±29.9Ba | 543.8±31.0Ba | 542.2±27.6Ba | 537.1±30.4Ba | 529.7±27.7Da | 547.0±29.4Ba | 542.3±28.3C | |

| Average | 556.0±31.3Ba | 561.1±36.4Aa | 552.2±30.9Ba | 544.0±28.7Ba | 547.0±35.1Ca | 562.8±30.1Ba | 553.8±31.4B |

Note: Different Capital letters in the same list indicate significant pairwise differences within stand ages between components, and different lowercases indicate significant pairwise differences within components between stand ages (multiple comparisons test; P<0.05).

The average C content did not differ significantly within plantation components among stands of different ages (P>0.05). No obvious pattern relationships were detected between C contents and increasing stand age.

C content in the soil layer

The C content changed markedly with increasing soil depth in all six stands (P<0.01; Table 3). The value in the topsoil (0–10 cm depth) was 46.1% higher than the average at 100 cm depth.

Table 3. Carbon contents by soil depth in six differently aged Mytilaria laosensis plantation stands (values are means ±SE, n = 12; g kg−1).

| Soil depth (cm) | 7 yr old | 10 yr old | 18 yr old | 23 yr old | 29 yr old | 33 yr old | Mean |

| 0–10 | 28.1±4.2A | 27.4±2.8A | 29.6±2.9 A | 31.7±2.4AB | 39.7±4.3C | 47.1±5.7D | 33.9±3.4 |

| 10–30 | 23.2±2.7A | 24.7±2.1A | 26.3±1.7B | 26.6±2.3B | 27.7±1.8B | 31.0±2.5C | 26.6±2.4 |

| 30–50 | 18.9±2.4A | 19.4±2.7A | 18.6±1.9A | 19.0±2.6A | 19.4±3.1A | 20.5±3.4A | 19.3±3.0 |

| 50–100 | 10.9±1.5A | 11.3±1.7A | 13.2±2.3B | 12.8±2.0B | 14.4±2.4C | 15.4±2.7C | 13.0±2.3 |

| Mean | 20.3±2.5 | 20.7±2.3 | 21.9±2.7 | 22.5±2.4 | 25.3±3.2 | 28.5±3.7 | 23.2±2.7 |

Note: Different capital letters indicate significant pairwise differences within soil depths between stand ages (multiple comparisons test; P<0.05).

The C contents of the two shallowest soil layers (0–10 cm and 10–30 cm), the horizon at 50–100 cm and values obtained by summing across all soil layers increased significantly with increasing stand age (P<0.05). The C content in the 3050 cm soil layer, however, did not differ significantly among different ages (P>0.05).

C stocks in plantation stands

Biomass and C stocks in tree layers

The allometric relationship between the biomass of the tree organs (W) and DBH (D) andheight (H) were best-fitted with equations in the form W = a(D 2 H)b. The F-tests showed that all regressions were highly significant (P<0.01). Biomass calculations based on these allometric equations were used in the estimations of C stocks detailed in Table 4.

Table 4. Individual biomass regressions models for Mytilaria laosensis trees (n = 18 for all models); W, biomass; D, DBH; H, height.

| Organ | Allometric equation | R 2 | F-value | P |

| Stem | W s = 0.1740(D 2 H)0.7661 | 0.9196 | 104.3812 | <0.0001 |

| Bark | Wba = 0.0220(D2H)0.7081 | 0.7191 | 58.6375 | <0.0001 |

| Branches | Wbr = 0.0002(D 2 H)1.2696 | 0.6291 | 11.2124 | 0.0065 |

| Leaves | Wl = 0.00003(D)1.2634 | 0.8091 | 41.0306 | 0.0001 |

| Roots | Wr = 0.0094(D 2 H)0.9538 | 0.7247 | 14.7872 | 0.0027 |

| Total tree | Wt = 0.1536(D 2 H)0.8268 | 0.9049 | 64.8073 | <0.0001 |

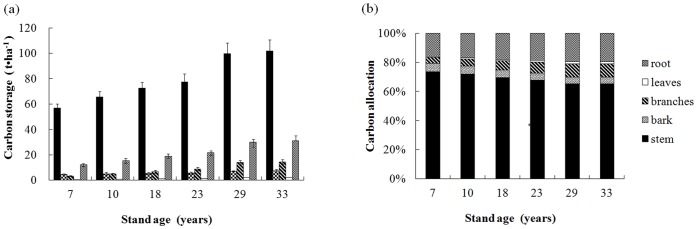

Fig. 1a depicts C stocks in stands of different ages and their allocation among component organs. The total C stocks in the trees were 77.3, 91.3, 104.1, 114.6, 153.0 and 156.2 t ha−1 in 7-, 10-, 18-, 23-, 29- and 33-year-old stands, respectively. Thus, stocks rapidly increased with age from 7 to 29 years, but plateaued thereafter. C stocks in stems made up 74.0, 72.1, 69.7, 67.7, 65.3 and 65.2% of the total tree content in 7-, 10-, 18-, 23-, 29- and 33-year-old stands, respectively. Furthermore, trends in the C stocks of stems, roots, bark, branches and leaves tracked those of total tree C stocks across all stand ages.

Figure 1. Carbon stocks and their allocation to tree components in six differently aged Mytilaria laosensis stands.

Values in (a) are means ±SE, n = 4. Note: Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences between means (multiple comparisons test; P<0.05).

The allocation of C stocks to stems and bark decreased with stand age from 7 to 29 years; stem and bark allocations were similar in 29- and 33-year-old stands. In contrast, C allocations to branches, leaves and roots increased with stand age from 7 to 29 years, but were similar in 29- and 33-year-old stands.

C stocks in the shrub, herb and litter layers

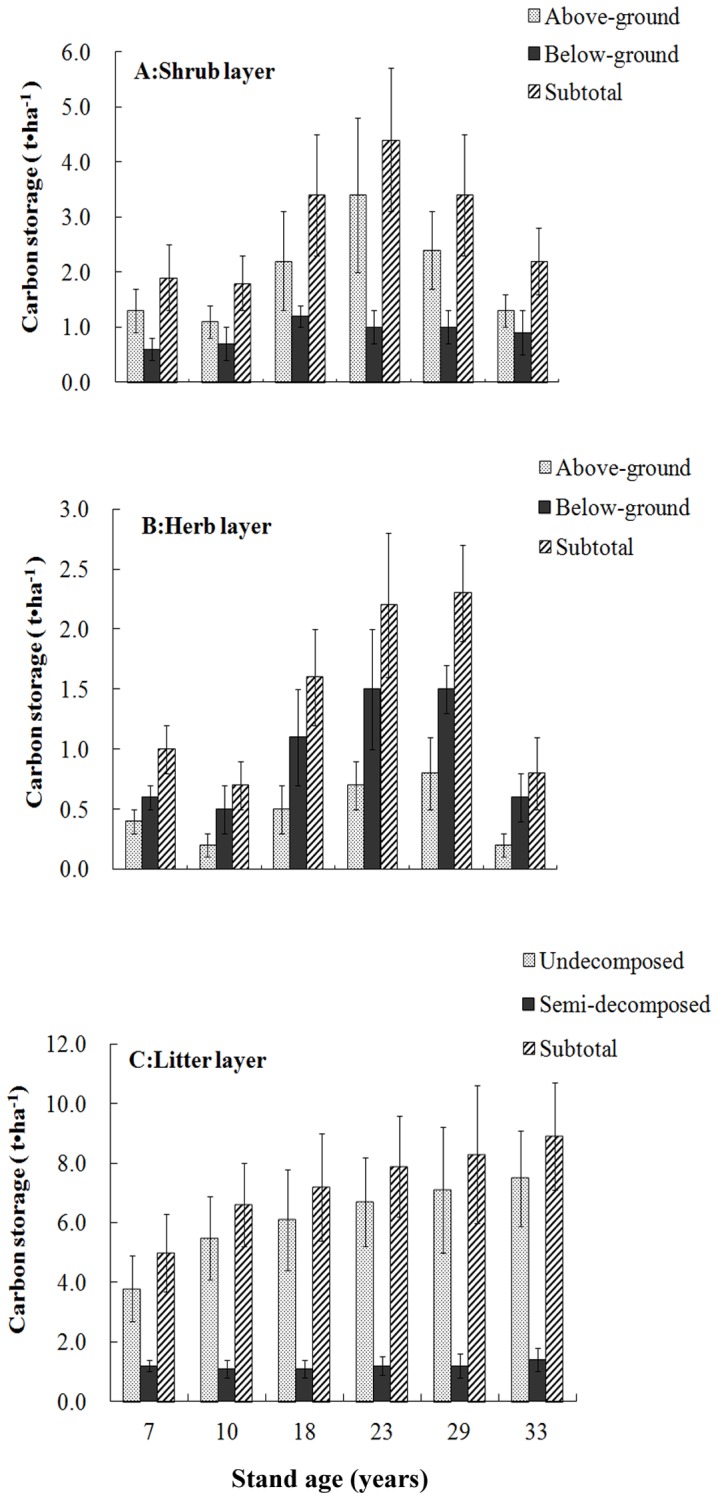

The C stock levels of each layer of the six plantation stands are shown in Fig. 2. Small proportions of biomass and C were measured in the shrub, herb and litter layers. The summed C contents of the shrub, herb and litter layers made up 2.9%, 3.0%, 3.6%, 4.0%, 3.2% and 2.6% of the total C in 7-, 10-, 18-, 23-, 29- and 33-year-old stands, respectively. The above-ground C stocks in the shrub layers of the six stands were higher than below-ground shrub stocks. However, above-ground biomass and C stocks in the herb layer were lower than those below ground. The undecomposed biomass and C stocks in the litter layer were higher than those in the semi-decomposed portion; the highest average C stock in the undecomposed litter was 5.1-fold higher than that in the semi-decomposed portion.

Figure 2. Carbon stocks in the shrub, herb and litter layers in six differently aged Mytilaria laosensis stands.

Values are means ±SE, n = 4.

Forest ground vegetation C stocks were correlated with stand age across the entire plantation chronosequence. The shrub C stocks increased with stand age from 7 to 23 years (P<0.05), but decreased with stand age from 23 to 33 years (P<0.05). Herb C stocks increased with stand age from 7 to 29 years, but decreased thereafter. C stocks in semi-decomposed portions of the litter layer were not related to stand age, but those in undecomposed portions and in the combined litter layer increased remarkably with increasing stand age (P<0.05). We therefore predict that the C stock in the litter layer will increase continually as the stands become older.

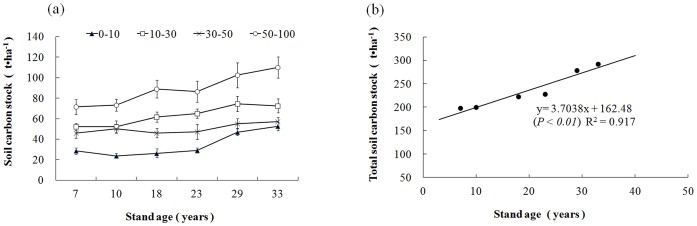

C stock in the soil layer

C stocks decreased with increasing soil depth even though the soil bulk density increased with depth. Fig. 3 depicts trends in the soil layer C stock across the M. laosensis stand age sequence. The top soil (0–10 cm) and deeper soil (50–100 cm) stocks followed an increasing trend with stand age (P<0.05), especially in the older stands (the difference between 29- and 33-year-old stands was especially significant; P<0.01). Although soil C stocks in the 10–30-cm and 30–50-cm horizons increased with age, the relationship was not significant (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. Soil layer carbon stocks in six differently aged Mytilaria laosensis stands (a) and the linear relationship between soil carbon stocks and stand age (b).

Values are means ±SE n = 12. Soil depth ranges in the key to (a) are in cm units.

Summed C stocks from 0 to 100 cm soil depth were 198.2, 199.6, 222.8, 227.9, 278.7 and 292.0 t ha−1 in the 7-, 10-, 18-, 23-, 29- and 33-year-old stands, respectively. This linear trend was significant (Fig. 3b).

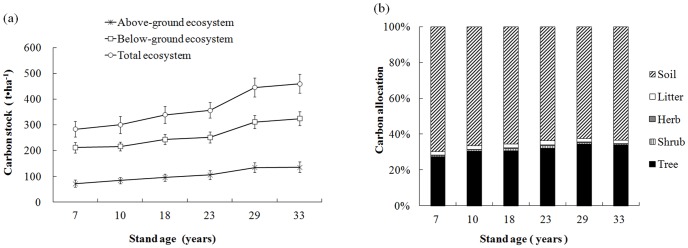

C stock in the plantation ecosystem

Table 5 summarises individual ecosystem C stocks measured within each of the six stands. The rank order of C stock proportions across the six stands was as follows: soil layer (62.6–70.0%) > tree layer (27.3–33.9%) > litter layer (1.8–2.2%) > shrub layer (0.5–1.3%) > herb layer (0.2–0.6). Averaging across stands, 65.3% of the total C was in the soil and 31.5% in the trees (Fig. 4b).

Table 5. Carbon stocks and their allocation in six differently aged Mytilaria laosensis stands (values are means ±SE, n = 4; t ha−1).

| Layers | Components | 7 yr old | 10 yr old | 18 yr old | 23 yr old | 29 yr old | 33 yr old | |

| tree layer | stem | 56.8±3.4F | 65.5±4.2E | 72.3±4.7D | 77.4±6.3C | 99.8±8.5B | 101.6±9.1A | |

| bark | 4.5±0.5D | 5.0±1.0C | 5.4±0.6B | 5.6±0.8B | 7.1±0.4A | 7.2±1.3A | ||

| branches | 3.2±0.4E | 4.7±0.7D | 6.7±1.3C | 8.7±1.4B | 13.9±1.7AB | 14.4±1.7A | ||

| leaves | 0.5±0.2E | 0.7±0.1D | 1.0±0.1C | 1.3±0.1B | 2.1±0.2AB | 2.2±0.3A | ||

| total above-ground tree | 65.0±2.9E | 75.9±4.5D | 85.4±4.9C | 93.0±5.8B | 122.9±9.2AB | 125. 4±10.4A | ||

| root | 12.3±0.9E | 15.4±1.7D | 18.7±2.1C | 21.6±1.4B | 30.1±2.3AB | 30.8±4.2A | ||

| subtotal | 77.3±4.4E | 91.3±4.7D | 104.1±5.1C | 114.6±6.2B | 153.0±8.4AB | 156.2±10.3A | ||

| shrub layer | above-ground | 1.3±0.4C | 1.1±0.3D | 2.2±0.9B | 3.4±1.4A | 2.4±0.7 B | 1.3±0.3C | |

| below-ground | 0.6±0.2D | 0.7±0.3C | 1.2±0.2A | 1.0±0.3AB | 1.0±0.3 AB | 0.9±0.4B | ||

| subtotal | 1.9±0.6D | 1.8±0.5D | 3.4±1.1B | 4.4±1.3A | 3.4±1.1B | 2.2±0.6C | ||

| herb layer | above-ground | 0.4±0.1B | 0.2±0.1C | 0.5±0.4B | 0.7±0.2A | 0.8±0.3A | 0.2±0.1C | |

| below-ground | 0.6±0.1C | 0.5±0.2C | 1.1±0.4B | 1.5±0.5A | 1.5±0.2A | 0.6±0.2C | ||

| subtotal | 1.0±0.2C | 0.7±0.2D | 1.6±0.4B | 2.2±0.6A | 2.3±0.4A | 0.8±0.3D | ||

| litter layer | undecomposed | 3.8±0.1.1D | 5.5±1.4C | 6.1±1.7B | 6.7±1.5B | 7.1±2.1A | 7.5±1.6A | |

| semi-decomposed | 1.2±0.2B | 1.1±0.3B | 1.1±0.3B | 1.2±0.3B | 1.2±0.4B | 1.4±0.4A | ||

| subtotal | 5.0±1.3E | 6.6±1.4D | 7.2±1.8C | 7.9±1.7B | 8.3±2.3AB | 8.9±1.8A | ||

| soil layer | 0–10 | 28.5±3.2E | 23.9±2.4F | 26.3±4.2D | 29.1±2.5C | 46.9±3.4B | 52.6±4.1A | |

| 10–30 | 52.2±3.4D | 52.1±5.8D | 61.7±4.8C | 65.1±4.6B | 74.3±7.4A | 72.5±6.7A | ||

| 30–50 | 46.1±5.1C | 50.3±4.4B | 45.9±4.7C | 47.4±7.4BC | 55.2±4.6A | 57.0±4.1A | ||

| 50–100 | 71.4±7.4E | 73.3±5.7E | 88.8±8.6D | 86.3±10.4C | 102.3±12.3B | 109.9±10.3A | ||

| subtotal | 198.2±12.4E | 199.6±10.3E | 222.7±11.4D | 227.9±13.2C | 278.7±17.3B | 292.0±16.4A | ||

| above-ground ecosystem | 71.7±14.2E | 83.8±12.4D | 95.3±14.2C | 105.0±17.6B | 134.4±18.8A | 135.8±20.4A | ||

| below-ground ecosystem | 211.7±20.4F | 216.2±17.8E | 243.7±19.4D | 252.0±21.3C | 311.3±25.6B | 324.3±27.3A | ||

| total ecosystem | 283.4±30.4F | 300.0±34.1E | 339.0±33.7D | 357.0±29.8C | 445.7±37.1B | 460.1±36.4A | ||

Note: Different Capital letters in the same row indicate significant pairwise differences within components between stand ages; (multiple comparisons test; P<0.05).

Figure 4. Carbon stocks in ecosystem components (a) and their proportional allocation (b) in six differently aged Mytilaria laosensis stands.

Values in (a) are means ±SE, n = 4.

Fig. 4a shows changes in C stocks in above-ground, below-ground and total ecosystem components with increasing stand age. Above-ground ecosystem C stocks increased as stand age increased from 7 to 29 years; thereafter, the C content changed little. Below-ground and total ecosystem C stocks increased across the entire age range.

The above-ground to below-ground ecosystem C stock ratios were 0.338, 0.388, 0.391, 0.417, 0.431 and 0.419 in the 7-, 10-, 18-, 23-, 29- and 33-year-old stands, respectively; the ratios increased gradually with age due to the accumulation of above-ground C in tree biomass.

Discussion

C content

C content in forest ecosystems varies by forest type. Tree species and site conditions are related to the C content [35], [43]. Across six M. laosensis stands with different ages, we detected a significant difference in mean C contents among different tree organs. No significant effect of stand age was detected within individual tree organs in the M. laosensis plantations, which corroborates the findings of studies on other species [38], [45].

The C contents of the various vegetation layers in the same stand fell into the following rank order: trees > shrubs > herbaceous plants (Table 2). Trees are probably high ranking because they can synthesise and accumulate more organic matter than can other types of vegetation [46].

The C content of litter varies with many factors, such as tree species, litter productivity, decomposition rate and microenvironment [35], [44]. Litter reportedly decomposes at a considerably faster rate in broadleaf forests than in coniferous stands; thus, the standing stock of C is lower in broadleaf forests [35]. We measured a mean litter C content of 553.8 g kg−1 in M. laosensis stands. This value is considerably higher than that in P. massoniana stands (505.9 g kg−1) in subtropical China [43], probably because the leaves of M. laosensis, which were the main component of the litter layer, are very leathery and refractory [47].

The mean C content of the soil layers in each stand decreased as the depth increased. The C content in the topsoil was higher than that in the deeper soil because the organic C produced from the decomposition of litter and root systems near the ground surface had entered the topsoil first, as demonstrated in other studies [10], [48], [49]. The C contents of the top two soil layers (0–10 cm and 10–30 cm), the deepest layer (50–100 cm) and across all soil layers significantly increased with increasing stand age, probably due to the increasing litter productivity in older stands. This finding helps to explain the increase in below-ground C stocks as stands age.

C stocks in plantation stands

Estimating the C stock pools stored in age-sequenced plantations may contribute to forest management for C sequestration. C stocks in trees depend on stand density, biomass and relative C contents in the tissues. We found that C contents were positively correlated with C stocks (Table 5). The tree C stocks increased rapidly with age from 7 to 29 years, but plateaued thereafter, perhaps due to declining tree growth rates. Most previous studies have reported increases throughout the growth phases of trees [10], [38]. The laws of growth may vary among tree species, For example, Euclyptus urophylla ×E.grandis grew faster in its early years, but turned slowly later, On the contrary, Castanopsis hystrix grew faster in the later stage than that in the early years [35], [38], [39], [45], that is to say, different tree species show different growth charactersAs to Mytilaria laosensis, itneeds 25–30 years to reach the largest yield stage [28]. This variation may account for the difference between Mytilaria laosensis plantations and most other stands.

Only small portions of biomass and C were sequestered in the shrub, herb and litter layers, which accounted for only 2.6–4.0% of the total. We detected a correlation between forest ground vegetation C stock and stand age across the entire chronosequence. C stocks in ground vegetation increased in the early stages of tree stand development, but decreased in older stands in concert with changes in tree canopy cover and stand density. Nevertheless, no obvious common patterns have been detected in studies on ground vegetation C storage. In the litter layer, the undecomposed and the total litter C stock decreased markedly with increasing stand age, which probably accounts for increases in soil C content with increasing stand age.

Soil was the largest C pool in the six stands that we studied. Soil C stock depends on stand age, the physical and chemical properties of the soil, forest type, litter productivity and litter decomposition rate [6], [35], [43], [50]. We found a significant linear relationship between total soil C stocks across the 0–100-cm-depth range and stand age. Hence, the proportion of C stock below ground will probably increase over protracted periods in the future life of the plantation ecosystems we studied.

Proportions of plantation ecosystem C stocks in the six stands fell into the following rank order: soil layer > tree layer > litter layer > shrub layer > herb layer. Soil and tree biomass harboured the largest C pools in the ecosystems, accounting for 96.8% of the total. These findings are congruent with previous studies [51], [52], [53], [54].

Above-ground ecosystem C stocks increased during the early stages of stand development and plateaued after 29 years due to a deceleration in tree growth. However, below-ground and total ecosystem C stocks increased with the stand age during the whole chronosequence we studied.

Conclusions

Stand age is a major determinant of C stocks in plantations. Both the C stocks and their distributions among plantation ecosystem components were affected by stand age. We found no significant differences in C contents in above-ground components among stand ages, but the soil C content increased with increasing stand age. Tree C was the largest above-ground ecosystem fraction, which contributed 25.7% to the total ecosystem C stocks in all six stands. The soil fraction was the largest C pool across plantations. C stocks across the 0–100 cm soil depth range increased across the entire chronosequence. They were significantly linearly related to tree growth. The increase in above-ground tree biomass with increasing stand age significantly affected the above-ground ecosystem C stock size. The increases in below-ground ecosystem C stocks through a 7-year to 33-year stand chronosequence were mainly attributable to increases in soil organic C. Thus, one must take into account the successional development in forest ecosystem C pools when estimating C sink potentials over the complete life cycle of plantation stands.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hui Wang, Dongjing Sun, Ji Zeng, You Nong, Haolong Yu, Jixin Tang, Henghui Wen, Yi Tao, Riming He, Hai Chen and Dewei Huang for their assistance in field sampling and data collection. We also thank Zhaoying Li, Lili Li and Bin He for their help in laboratory chemical analyses. We also acknowledge the helpful comments and suggestions of manuscript reviewers.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

Our research was financially supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Non-profit Research Institution of CAF (No. CAFYBB2014QA033), Nature Science Foundation of Guangxi (No 2014jjBA30073), The Ministry of Science and Technology (2012BAD22B01), National Science Foundation of China (No 31400542), and the Director Foundation Project of the Experimental Centre of Tropical Forestry, Chinese Academy of Forestry (No. RL2011–02). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Choi SD, Lee K, Chang YS (2002) Large rate of uptake of atmospheric carbon dioxide by planted forest biomass in Korea. Global Biogeochemistry Cycle 16: 1089. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goodale CL, Apps MJ, Birdsey RA, Field CB, HeathLS, et al (2002) Forest carbon sinks in the Northern Hemisphere. Ecological Applications 12: 891–899. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Houghton RA (2005) Aboveground forest biomass and the global carbon balance. Global Change Biology 11: 945–958. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Litton CM, Raich JW, Ryan MG (2007) Carbon allocation in forest ecosystems. Global Change Biology 13: 2089–2109. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown S (2002) Measuring carbon in forests: current status and future challenges. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 116: 363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gower ST (2003) Patterns and mechanisms of the forest carbon cycle. Annual Review of Environment and Resource 28: 169–204. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Houghton RA (2007) Balancing the global carbon budget. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 35: 313–347. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kurz WA, Beukema SJ, Apps MJ (1996) Estimation of root biomass and dynamics for the carbon budget model of the Canadian forest sector. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 26: 1973–1979. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vogt K (1991) Carbon budgets of temperate forest ecosystems. Tree Physiology 9: 69–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peichl M, Arain MA (2006) Above- and belowground ecosystem biomass and carbon pools in an age-sequence of temperate pine plantation forests. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 140: 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peichl M, Arain MA (2007) Allometry and partitioning of above- and belowground tree biomass in an age-sequence of white pine forests. Forest Ecology and Management 253: 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taylor AR, Wang JR, Chen HYH (2007) Carbon storage in a chronosequence of red spruce (Picea rubens) forests in central Nova Scotia. Canada. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 37: 2260–2269. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paquette A, Messier C (2010) The role of plantations in managing the world's forests in the Anthropocene. Frontiers in the Ecology and Environment 8(1): 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Department of Forest Resources Management, SFA (2010) The 7th National forest inventory and status of forest resources. Forest Ecology and Management 1: 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.SFA (State Forestry Administration) (2007) China's Forestry 1999–2005. China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing, China.

- 16. He Y, Li Z, Chen J, Liu Y, Liu D, et al. (2008) Sustainable management of planted forests in China: comprehensive evaluation, development recommendation and action framework. Chinese Forest Science and Technology 7: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jagger P (2003) The role of trees for sustainable management of less favored lands: the case of Eucalyptus in Ethiopia. Forest Policy and Economics 5: 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peng SL, Wang DX, Zhao H, Yang T (2008) Discussion the status quality of plantation and near nature forestry management in China. Journal of Northwest Forestry University 23: 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poore ME, Fries C (1985) The ecological effects of Eucalyptus. FAO Forestry p 59: : 1–97, FAO, Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang H, Liu SR, Mo JM, Wang JX, Makeschin F, et al. (2010a) Soil organic carbon stock and chemical composition in four plantations of indigenous tree species in subtropical China. Ecological Research 25: 1071–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Borken W, Beese F (2005) Soil carbon dioxide efflux in pure and mixed stands of oak and beech following removal of organic horizons. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 35: 2756–2764. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Borken W, Beese F (2006) Methane and nitrous oxide fluxes of soils in pure and mixed stands of European beech and Norway spruce. European Journal of Soil Science 57: 617–625. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kraenzel M, Castillo A, Moore T, Potvin C (2002) Carbon storage of harvest-age teak (Tectona grandis) plantations, Panama. Forest Ecology and Management 5863: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Laclau P (2003) Biomass and carbon sequestration of ponderosa pine plantations and native cypress forests in northwest Patagonia. Forest Ecology and Management 180: 317–333. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vesterdal L, Schmidt IK, Callesen I, Nilsson LO, Gundersen P (2008) Carbon and nitrogen in forest floor and mineral soil under six common European tree species. Forest Ecology and Management 255: 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang H, Liu SR, Mo JM, Zhang T (2010b) Soil–atmosphere exchange of greenhouse gases in subtropical plantations of indigenous tree species. Plant and Soil 335: 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yuan SF, Ren H, Liu N, Wang J, Guo QF (2013) Can thinning of overstorey trees and planting of native tree saplings increase the establishment of native trees in exotic Acacia plantations in South China? Journal of Tropical Forest Science 25: 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guo WF, Cai DX, Jia HY, Li YX, Lu ZF (2006) Growth laws of Mytilaria laosensis plantation. Forest Research 19: 585–589. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li YX, Tan TY, Huang JG, Feng YQ (1988) A preliminary report on the densities of Mytilaria laosensis plantation. Forest Research 1: 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liang RL (2007) Current situation of Guangxi indigenous broadleaf species resource and their development counter-measures. Guangxi Forest Science 36: 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin DX, Han JF, Xiao ZQ, Hong CF (2000) Mytilaria laosensis improved on the soil physical & chemical properties. Journal of Fujian College of Forestry 20: 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lin JG, Zhang XZ, Weng X (2004) Effects of site conditions on growth and wood quality of Mytilaria laosensis plantations. Journal of Plant Resources and Environment 13: 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ming AG, Jia HY, Tao Y, Lu LH, Su JM, et al. (2012) Biomass and its allocation in 28-year-old Mytilaria laosensis plantation in southwest Guangxi. Chinese Journal of Ecology 31: 1050–1056. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jonard M, Andre F, Jonard F, Mouton N, Proces P, et al. (2007) Soil carbon dioxide efflux in pure and mixed stands of oak and beech. Annual of Forest Science 64: 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kang B, Liu S, Zhang G, Chang J, Wen Y, et al. (2006) Carbon accumulation and distribution in Pinus massoniana and Cunninghamia lanceolata mixed forest ecosystem in Daqingshan, Guangxi of China. Acta Ecological Sinica 26: 1321–1329. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kasel S, Bennett TL (2007) Land-use history, forest conversion, and soil organic carbon in pine plantations and native forests of south eastern Australia. Geoderma 137: 401–413. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li X, Yi MJ, Son Y, Park PS, Lee KH, et al. (2011) Biomass and Carbon Storage in an Age-Sequence of Korean Pine (Pinus koraiensis) Plantation Forests in Central Korea. Journal of Plant Biology, 54 (1): 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu E, Wang H, Liu SR (2012) Characteristics of carbon storage and sequestration in different age beech (Castanopsis hystrix) plantations in south subtropical area of China. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 23: 335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ming AG, Jia HY, Tian ZW, Tao Y, Lu LH, et al. (2014) Characteristics of carbon storage and its allocation in Erythrophleum fordii plantations with different ages. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 25(4): 940–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soil Survey Staff of Usda (2006) Keys to Soil Taxonomy. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Natural Resources Conservation Service, Washington, DC, USA.

- 41.State Soil Survey Service Of China (1998) China Soil. China Agricultural Press, Beijing, China.

- 42. Wang WX, Shi ZM, Luo D, Liu SR, Lu LH, et al. (2013) Carbon and nitrogen storage under different plantations in subtropical south China. Acta Ecological Sinica 33: 925–933. [Google Scholar]

- 43. He YJ, Qin L, Li ZY, Liang XY, Shao MX, et al. (2013) Carbon storage capacity of monoculture and mixed-species plantations in subtropical China. Forest Ecology and Management 295: 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou Y, Yu Z, Zhao S (2000) Carbon storage and budget of major Chinese forest types. Acta Phytoecology. Sinicea 24: , 518–522. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liang HW, Wen YG, Wen LH, Yin QC, Huang XZ, et al. (2009) Effects of continuous cropping on the carbon storage of Eucalyptus urophylla ×E. grandis short rotations plantations. Acta Ecological Sinica 29: 4242–4250. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cleveland C, Townsend A, Taylor P, Alvarez-Clare S, Bustamante M, et al. (2011) Relationships among net primary productivity, nutrients and climate in tropical rain forests: a pan-tropical analysis. Ecology Letters 14: : 939–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lu LH, Cai DX, Jia HY, He RM (2009) Annual variations of nutrient concentration of the foliage litters from seven stands in the southern subtropical area. Scientia Silvae Sinicae 45: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tian D, Yin G, Fang X, Yan W (2010) Carbon density, storage and spatial distribution under different ‘Grain for Green’ patterns in Huitong, Hunan province. Acta Ecological Sinica 30: 6297–6308. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang H, Guan DS, Song MW (2012) Biomass and carbon storage of Eucalyptus and Acacia plantations in the Pearl River Delta, South China. Forest Ecology and Management 277: 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jandl R, Lindner M, Vesterdal L, Bauwens B, Baritz R, et al. (2007) How strongly can forest management influence soil carbon sequestration? Geoderma 137: 253–268. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Grigal DF, Ohmann LF (1992) Carbon storage in upland forests of the Lake States. Soil Science Society of America Journal 56: 935–943. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang H, Liu SR, Wang JX, Shi ZM, Lu LH, et al. (2013) Effects of tree species mixture on soil organic carbon stocks and greenhouse gas fluxes in subtropical plantations in China. Forest Ecology and Management 300: 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang FM, Xu X, Zou B, Guo ZH, Li ZA, et al. (2013) Biomass Accumulation and Carbon Sequestration in Four Different Aged Casuarina equisetifolia Coastal Shelterbelt Plantations in South China. PLOS ONE 8(10): e77449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhao JL, Kang FF, Wang LX, Yu XW, Zhao WHH, et al. (2014) Patterns of Biomass and Carbon Distribution across a Chronosequence of Chinese Pine (Pinus tabulaeformis) Forests. PLOS ONE 9(4): e94966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper.