Abstract

Background

During the earlier years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, initial reports described sensorineural hearing loss in up to 49% of individuals with HIV/AIDS. During those years, patients commonly progressed to advanced stages of HIV disease, and frequently had neurological complications. However, the abnormalities on pure-tone audiometry and brainstem evoked responses outlined in small studies were not always consistently correlated with advanced stages of HIV/AIDS. Moreover, these studies could not exclude the confounding effect of concurrent opportunistic infections and syphilis. Additional reports also have indicated that some antiretroviral (ARV) medications may be ototoxic, thus it has been difficult to make conclusions regarding the cause of changes in hearing function in HIV-infected patients. More recently, accelerated aging has been suggested as a potential explanation for the disproportionate increase in complications of aging described in many HIV-infected patients, hence accelerated aging associated hearing loss may also be playing a role in these patients.

Methods

We conducted a large cross-sectional analysis of hearing function in over 300 patients with HIV-1 infection and in 137 HIV-uninfected controls. HIV-infected participants and HIV-uninfected controls underwent a two-hour battery of hearing tests including the Hearing Handicap Inventory, standard audiometric pure-tone air and bone conduction testing, tympanometric testing and speech reception and discrimination testing.

Results

Three-way ANOVA and logistic regression analysis of 278 eligible HIV-infected subjects stratified by disease stage in early HIV disease (n= 127) and late HIV disease (n=148) and 120 eligible HIV-uninfected controls revealed no statistical significant differences among the three study groups in either overall 4-PTA or hearing loss prevalence in either ear. Three-way ANOVA showed significant differences in word recognition scores (WRS) in the right ear among groups; a significant group effect on tympanogram static admittance in both ears, and a significant group effect on tympanic gradient in the right ear. There was significantly larger admittance and gradient in controls as compared to the HIV-infected group at late stage of disease. Hearing loss in the HIV-infected groups was associated with increased age and was similar to that described in the literature for the general population. Three-way ANOVA analysis also indicated significantly greater pure tone thresholds (worse hearing) at low frequencies in HIV patients in the late stage of disease compared with HIV-uninfected controls. This difference was also found by semi-parametric mixed effects (SPME) models.

Conclusions

Despite reports of “premature” or “accelerated” aging in HIV-infected subjects, we found no evidence of hearing loss occurring at an earlier age in HIV-infected patients compared to HIV-uninfected controls. Similar to what is described in the general population; the probability of hearing loss increased with age in the HIV-infected subjects and was more common in patients over 60 years of age. Interestingly, HIV-infected subjects had worse hearing at lower frequencies and have significant differences in tympanometry compared to HIV-uninfected controls; these findings deserve further study.

Introduction

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has a preferential affinity for the central nervous system. Before the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), about 60% of patients with advanced HIV infection had evidence of neurological dysfunction during the course of their illness. Additionally, up to 20% of individuals reported having neurological manifestations as the first symptom of HIV disease (Levy et al. 1985). Earlier reports suggested that damage to the central auditory pathways by HIV-1 resulted in sensorineural hearing loss (Soucek & Michaels 1996; Hart et al. 1989). While hearing loss and abnormal audiometric testing were reported in some of these studies as associated with the use of antiretroviral (ARV) medications (Martinez & French 1993), opportunistic infections of the central nervous system and noise exposure were not exclusionary and could have contributed to the reported findings (Marra et al. 1997). An association between worsening hearing loss and progression of HIV disease has not been consistently demonstrated either (Mata et al. 2000; Monte et al. 1997). The small size of the samples in these studies, and the inclusion of individuals with other conditions that may affect auditory function, preclude firm conclusions based on their findings.

HIV-1 infection is characterized by progressive immune deficiency and sustained immune activation and inflammation. The rate of disease progression is highly variable and likely governed by complex interactions between viral and host factors. Although, neurological complications described in HIV disease commonly occur at advanced stages of the disease or in the presence of uncontrolled viral replication resulting from treatment failure, it has become evident that even with good control of plasma viremia, HIV can persist in the central nervous system and this viral persistence may be responsible for cognitive impairment which continues to be prevalent in particular among patients over 50 years of age. The persistence of HIV in the central nervous system has been attributed to less than optimal penetration of certain ARV medications, incomplete recovery of the immune system, persistent inflammation and immune activation or toxicity from ARV medications.

Certain ARV medications, through mitochondrial toxicity (Lewis & Dalakas 1995), could worsen the effects of aging on the auditory system. This could lead to accelerated changes on the cochlea or central auditory system similar to those described in aging humans and animal models (Kujoth et al. 2005). Age related hearing loss or presbycusis (Gates & Mills 2005) is common in the elderly and mutation in mitochondrial DNA has been linked with severity of presbycusis (Bai et al. 1997; Dai et al 2004; Pickles 2004; Markaryan et al. 2009).

Damaged mitochondrial DNA may cause reduced oxidative phosphorylation, which may lead to problems with neural functioning in the inner ear, may lead to narrowing of the vasa nervorum or a greater rate of apoptosis (Dai et al. 2004). Reduced perfusion of the cochlea associated with age may contribute to the formation of reactive oxygen metabolites, and cause damage to mitochondrial DNA. Accelerated aging and its characteristic co-morbidities have been reported in HIV-infected individuals (Hasse et al. 2011). It is thought that HIV infection leads to immunologic changes similar to those seen in HIV uninfected elderly persons and that much of this early senescence is related to inflammation and chronic immune activation (Deeks et al. 2012; Desai & Landay 2010).

Our previous estimates of the prevalence of auditory complaints based on data base queries showed that such complaints were present in 49% of HIV-subjects receiving care at our clinic. Either HIV-1 infection, toxicity secondary to the long-term use of ARV medications, early senescence, persistent inflammation or a combination of these factors is biologically plausible and may explain loss of hearing function in HIV-1 infection. It is crucial to establish the accurate prevalence of hearing impairment in individuals living with HIV/AIDS in order to understand its pathogenesis and assess potential prevention and treatment strategies.

To increase our understanding of the etiology and pathophysiology of hearing loss in HIV-1 infection, we designed a large prospective study intended to establish the characteristics, nature and degree of hearing loss, as well as the mechanism(s) involved in hearing impairment among HIV-infected individuals and in particular, whether HIV medications and disease stage influence auditory function.

Study Subjects

HIV-1 infected men and women over 18 years of age were recruited from the Infectious Diseases Clinic at the University of Rochester where over 1,000 individuals at different stages of HIV disease receive their care. Subject recruitment began in September 2009 and was completed in March 2012, 490 HIV-infected subjects were invited to participate in the study. Of those, 304 HIV-infected men and women consented to participate and underwent comprehensive baseline hearing tests. After completing informed-consent procedures, study volunteers underwent screening with standardized history and physical examination that included neurological examination and screening for peripheral neuropathy. To be eligible for participation, HIV-infected volunteers needed to have documentation of a positive HIV antibody test (Enzyme Immune Assay or EIA) and confirmatory Western blot, a passing score on a cognitive-screening test (mini-mental state examination), no active opportunistic infections and no history of ototoxic medications, neurological conditions, Meniere’s disease, labyrinthitis, type 1 diabetes, hypothyroidism, and chronic use of female hormone replacement therapy or exposure to chemotherapy agents.

Twenty-six HIV-infected subjects were excluded after the initial hearing test was completed at study entry, and were not eligible for analysis, 15 of those were identified as having noise related hearing loss and 5 had bilateral conductive hearing loss; an additional 3 subjects gave unreliable responses during the hearing tests, and 3 were found to have a neurological disorder that was exclusionary. The remaining 278 subjects were eligible for analysis. Participants were stratified according to stage of HIV disease. Late disease stage was defined by the diagnosis of AIDS either due to having a history of an AIDS defining opportunistic infection or a CD4+ cell count of less than 200 cells/μL and early stage was defined by either asymptomatic or symptomatic HIV disease with CD4+ cell counts greater than 200 cells/μL and no history of AIDS defining conditions. The early disease group also included long term non-progressors which are HIV-infected individuals with well controlled HIV disease in absence of current antiretroviral therapy (ARVT).

HIV-uninfected controls were recruited from the community at large through the University of Rochester’s Research Subjects Review Board approved recruitment materials. Volunteers for this group consented to be tested for HIV. To be eligible to participate, they needed to have a negative HIV test, no known exposure to HIV in the previous 6 weeks, and needed to meet the same eligibility criteria used for the HIV-infected participants. Seventeen controls were excluded: 6 had bilateral noise notch, 10 had conductive or mixed hearing loss and one subject gave unreliable responses during the hearing test. Subjects with either noise induced hearing loss or a conductive hearing loss were eliminated as the authors attempted to control for as many confounding factors as possible. We attempted to determine the effect of the HIV disease on auditory system in isolation of these pathologies that can either be very transient (conductive hearing loss) or the result of acoustic trauma (noise induced hearing loss).

Methods

At enrollment, we recorded all measures related to the clinical management of the participants including the patient’s weight, blood pressure, temperature, heart rate, and oxygen saturation by finger oximetry, Karnofsky score, ARVT and the use of other medications. CD4+ cell counts, HIV-1 RNA plasma levels, vitamin D levels and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) were obtained. Baseline HIV-1 RNA plasma level, nadir CD4+ cell counts were recorded from the patient’s medical record along with ARVT regimen, type of medications, starting treatment dates and treatment response. We also assessed adherence to ARVT by subject’s report during each study visit.

Testing began after doing a thorough otoscopic examination. Any subject who had excessive cerumen, that was believed to potentially occlude the ear canal during testing, received an ear flush by a trained nurse or was referred for cerumen management before testing when ear flushing was unsuccessful. Each subject then completed two questionnaires: the Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults which is administered via paper and pen and a detailed noise exposure questionnaire administered by the audiologists. The Hearing Handicap Inventory is designed to assess the emotions and attitudes one has to one’s perceived hearing abilities or inabilities in different everyday listening situations by rating either a yes, no or sometimes response to a specific situation. The noise exposure questionnaire (adapted from Bergmeyer, 2009), was used in an attempt to quantify the duration of exposure and frequency of use of hearing protection in both work and recreational activities. The work exposure portion of the questionnaire was modified to quantify the years of exposure, the average daily exposure in hours, work environment, noise source directionality and whether the individual used hearing protection (always, sometimes or never) while the recreational exposure was broken down into seven discrete exposure activities such as: motor sports, firearms, musical instruments, the usage of personal music devices, lawn power equipment, power tools and household appliances and heavy equipment or farm machinery. Similar to the work exposure section, we also modified the questionnaire to quantify noise exposure and how often an individual used hearing protection (always, sometimes or never) in the recreational environment.

Study participants then underwent a two-hour battery of baseline auditory tests in a sound proof booth (ANSI 3.6). Standard audiometric thresholds were obtained in each ear of both the control and HIV-infected subjects using EAR tone 3A insert earphones in octaves from 250 to 1000 Hz and octaves and inter-octaves from 1000-8000 Hz using standard audiometric testing techniques (Hughson and Westlake, 1944) on an Inter Acoustic AC40 diagnostic audiometer calibrated just prior to beginning the data collection and yearly thereafter (ANSI S3.21 2004 R 2009). In addition, bone conduction thresholds were obtained in at least one ear in octaves from 250 to 4000 Hz using a similar testing technique with a Radio Ear B71 bone oscillator.

A 4-frequency pure-tone average (4-PTA) was calculated using the thresholds at 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 kHz. Individuals were considered to have hearing loss if they had a pure-tone average of greater than 25 dB HL in either ear. Sensorineural hearing loss was defined as an air conducted 4-frequency pure-tone average greater than 25 dB HL in the absence of a significant air-bone gap (greater than or equal to a 10 dB air bone gap at 2 or more frequencies). A conductive hearing loss was defined as elevated air conduction thresholds (≥25 dB HL), normal bone conduction thresholds (≤25 dB HL), and the presence of an air-bone gap of 10 dB HL or greater at 2 or more frequencies. Mixed hearing loss was defined as elevated air and bone conduction thresholds (≥25 dB HL), with an air-bone gap of 10 dB HL or greater at 2 or more frequencies.

Speech testing was performed by initially obtaining monitored live voice speech reception thresholds in both ears under inserts (EAR tone 3A). Word recognition (discrimination) testing was completed by testing all individuals at a minimum of 50 dB HL using CD recorded W-22 half word lists. Higher levels were used in some individuals with hearing loss to assure audibility in the 2000 to 4000 Hz high-frequency region. The presentation level was set to be at least 15 dB Sensation Level (SL) above the 2000 Hz threshold while making sure the 4000 Hz region remained audible. Due to the severity of the high-frequency hearing loss of some individuals, a constant SL above 4000 Hz was not maintained, as we would reach the limits of the audiometric testing equipment. In addition, recorded Spanish speech reception threshold and word discrimination materials were used and a native Spanish-speaking member of the research team scored the Spanish speech materials for any participant for whom Spanish was the primary language (2/137 or 1.5% of the HIV-uninfected control group and 34/278 or 12% of the HIV-infected group).

Acoustic Immittance testing was administered using a GrasonStadler GSI Tympstar. A 226 Hz probe tone was used, and the ear canal volume (ml), peak pressure (daPa), static admittance (mmho) and tympanometric width (daPa) were obtained.

A summary report was written and the subject’s clinic provider was notified of any abnormalities in the audiologic evaluation. Fifty-two HIV-infected participants (19%) were referred to otolaryngology and/or Audiology for further evaluation; 4/52 (8%) were found to be candidates for amplification. Sixteen HIV-uninfected controls (13%) were referred for further evaluation to otolaryngology and/or Audiology, 2/16 (13%) were found to be candidates for amplification.

Statistical Analysis

The χ2 test was used to test correlation among categorical variables and the two-sample t-test or one-way ANOVA was used to compare continuous variables between groups. Logistic regression was applied to study the joint effect of HIV status, ethnicity, sex, age, HIV duration, recent viral loads, recent CD4+ and the lowest (nadir) CD4+ counts on hearing status. Three-way ANOVA was used to explore how hearing and tympanometry variables were affected by group (control, HIV early, HIV late), age and sex.

Transformations were necessary in the analyses to meet the normality assumption of the ANOVA, however data were back transformed for reporting purposes here. The natural log transformation was applied to the static admittance in the tympanometry. To take into account the large number of zeros in responses (over 50% zeroes), a zero-inflated Gamma Model (ZIG) was used to investigate how the Hearing Handicap Inventory for Adults (HHI-A) and work noise exposure from the questionnaires were affected by group, age and sex. Finally, a semi-parametric mixed effect model (SPME), which models frequency non-parametrically and accounts for within-subject correlation of pure-tones thresholds, was applied to explore the effects of group on pure-tone thresholds, controlling for age (in decades) and sex. Sex was subsequently dropped from the model by the likelihood ratio test. The Tukey-Kramer method was used to control type I error for all multiple comparisons.

Results

HIV-infected subjects

Demographic and baseline characteristics for study groups HIV early stage, HIV late stage and HIV-uninfected controls are presented in Table 1, groups are compared using χ2 or one way ANOVA.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Subjects.

| Variable | HIV-Early* 127 |

HIV-Late* 148 |

Control 120 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | <0.01 | |||

| Male | 94 (74.0%) | 100 (67.6%) | 37 (30.8%) | |

| Female | 33 (26.0%) | 48 (32.4%) | 83 (69.2%) | |

| Age (in decades) | <0.01 | |||

| Less than 25 | 11 (8.7%) | 4 (2.7%) | 15 (12.5%) | |

| 25 – 34 | 21 (16.5%) | 11 (7.4%) | 24 (20.0%) | |

| 35 – 44 | 25 (19.7%) | 29 (19.6%) | 23 (19.2%) | |

| 45 – 54 | 46 (36.2%) | 51 (34.5%) | 24 (20.0%) | |

| 55 – 64 | 18 (14.2%) | 45 (30.4%) | 29 (24.2%) | |

| 65 and over | 6 (4.7%) | 8 (5.4%) | 5 (4.1%) | |

| Mean (S.E.) | 43.9 (1.1) | 49.0 (0.9) | 43.4 (1.4) | <0.01 |

| Race ** | 0.04 | |||

| White | 51 (43.6%) | 59 (41.9%) | 69 (57.5%) | |

| African American | 49 (41.9%) | 68 (48.2%) | 37 (30.8%) | |

| Other | 17 (14.5%) | 14 (9.9%) | 14 (11.7%) | |

| Ethnicity *** | <0.01 | |||

| Hispanic | 28 (22.0%) | 23 (16.0%) | 8 (6.7%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 99 (78.0%) | 121 (84.0%) | 112 (93.3%) | |

| Hearing Function: n (%) | 0.29 | |||

| Normal * | 106 (83.5%) | 120 (81.1%) | 106 (88.4%) | |

| Hearing Loss (HL) | ||||

| Unilateral HL | 15 (11.8%) | 15 (10.1%) | 10 (8.3%) | |

| Bilateral HL | 6 (4.7%) | 13 (8.8%) | 4 (3.3%) |

Note:

3 subjects had unknown HIV disease stage

17 subjects had unknown race

4 subjects had unknown ethnicity. χ2 test for Sex, Race and Ethnicity. One-way ANOVA test for age (continuous).

Of the 278 HIV-infected subjects who were analysis-eligible, 197 (70.9%) were male, 111 (40.0%) were white and 118 (42.4%) were black and. 52 subjects (18.7%) identified themselves as Hispanic. One hundred and twenty-seven (45.7%) subjects were classified as HIV early stage, 148 (53.2%) classified as HIV late stage and 3 (1.1%) subjects were classified as of unknown HIV disease stage. The mean age for HIV-infected subjects in early stage of disease was 43.9 years (SE =1.1) and 49.0 years (SE =0.9) for HIV-infected subjects in late stage of disease.

Table 2 compares HIV disease characteristics for HIV-infected subjects with normal hearing and hearing loss. The mean age for the whole group was 46.6 years (SE=0.7) and the mean time of HIV diagnosis was 11.8 years (SE =0.5). The mean CD4+ cell count at HIV diagnosis was 436.6 (SE=21.7). The mean CD4+ cell count at study entry was 610.7 (SE =20.6). The mean nadir CD4+ cell count was 248.2 (SE =11.9). The mean of the log10 transformed value of baseline viral load was 4.40 copies/ml (SE =.07). The mean of the log10 transformed value viral load at study entry was 1.28 copies/ml (SE =.09).

Table 2. Characteristics of the HIV-infected Subjects by Group and according to Hearing Function.

| Variable | Entire group 278 |

Hearing Loss 49 |

Normal Hearing 229 |

p-value# |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV Disease Stage^ | 0.61 | |||

| HIV Early | 21 (16.5%) | 106 (83.5%) | ||

| HIV Late | 28 (18.9%) | 120 (81.1%) | ||

| Mean age in years (S.E.) | 46.6 (0.7) | 55.4 (1.6) | 44.9 (0.8) | <0.01 |

| Mean* HIV diagnosis in years (S.E.) | 11.8 (0.5) | 14.1 (0.9) | 11.3 (0.5) | 0.02 |

| Mean* CD4+ at HIV diagnosis cells/ μL (S.E.) |

436.6 (21.7) | 443.9 (50.8) | 435.1 (24.1) | 0.88 |

| Mean* CD4+ cell count at study entry cells/μL (S.E) |

610.7(20.6) | 551.6 (51.8) | 624.0 (22.4) | 0.17 |

| Mean* Nadir CD4+ cell count, cells/μL (S.E.) |

248.2 (11.9) | 200.8 (20.3) | 258.7 (13.8) | 0.02 |

| Mean* Baseline Viral load in log10 copies/ml (S.E.) |

4.40 (0.07) | 4.51 (0.16) | 4.38 (0.08) | 0.51 |

| Mean* Viral load at study entry in log10 copies/ml (S.E.) |

1.28 (0.09) | 1.43 (0.21) | 1.24 (0.10) | 0.43 |

Note:

3 subjects had unknown HIV stage

Mean Results display mean +/− standard error (S.E.)

p-value for comparison between hearing loss and normal hearing groups; χ2 test for HIV disease stage; two-sample t-test for all other variables shown.

Control Subjects

137 HIV-uninfected men and women consented to participate and underwent the same comprehensive audiologic testing protocol. Of the 120 HIV uninfected subjects eligible for analysis, 37 (30.8%) were males, 69 (57.5%) were white, 37 (30.8%) were black, 8 (6.7%) were Hispanic. The mean age of these subjects was 43.4 years (SE =1.4) as can be seen in Table 1.

Hearing test results

The overall descriptive analysis presented in Table 1 shows that of the HIV-infected group 49/278 (17.6%) had some degree of sensorineural hearing impairment compared to 14/120 (11.7%) of the non-infected controls, however we cannot rule out self-selection bias in the control group. Bilateral hearing loss was more prevalent among subjects at late stage of HIV disease; however the small numbers do not allow meaningful conclusions.

Hearing loss in the HIV-infected subjects is explored in Table 2 and was associated with longer duration of HIV diagnosis: 14.1 years, (SE=0.9) compared to 11.3 years (SE=0.5) for the HIV-infected group without hearing loss (p= 0.02). A lower mean nadir CD4+ cell count was also associated with hearing loss (200.8 cells/μL vs. 258.7 cells/ μL, p= 0.02) while mean baseline HIV viral load, CD4+ cell count at diagnosis and disease stage were not significantly different between groups. There was no difference in mean baseline viral load or mean viral load at entry between the HIV-infected groups (with and without hearing loss).

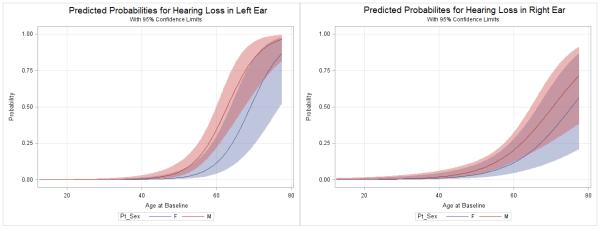

Similarly to what is reported for the general population, the probability of having hearing loss increased as the age of the HIV-infected participants increased and was higher for male versus female subjects at all ages. The logistic regression of hearing loss status on demographic variables (ethnicity, gender and age) and clinical variables (HIV status, HIV duration, HIV viral load at study entry, CD4+ cell count at study entry and nadir CD4+ cell count) indicated that the hearing loss was associated with age only (Table 3). Figure 1 shows this graphically, with the probability of the left ear 4-PTA greater than 25 dB HL increasing dramatically above ~55 years for men and ~65 for women. The right ear has a similar aging effect (not shown).

Table 3. Logistic Regression Analysis.

| Odds Ratio, 95% Confidence Intervals and p-values | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing Loss Status |

Effect | Odds Ratio |

95% Lower CI |

95% Upper CI |

p-value |

| Left Ear | Patient Sex (M vs. F) | 3.68 | 0.84 | 16.19 | 0.08 |

| Age | 1.26 | 1.15 | 1.38 | <.01 | |

| Group (Late vs. Early) | 0.70 | 0.11 | 4.37 | 0.70 | |

| Ethnicity (Non-Hispanic vs. Hispanic) |

0.96 | 0.19 | 4.97 | 0.96 | |

| HIV Duration | 1.01 | 0.93 | 1.10 | 0.80 | |

| Recent VL (log10) | 1.00 | 0.64 | 1.57 | 0.98 | |

| Recent CD4+ | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.52 | |

| CD4+ Nadir | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.27 | |

| Right Ear | Patient Sex (M vs. F) | 1.77 | 0.47 | 6.72 | 0.40 |

| Age | 1.16 | 1.08 | 1.24 | <.01 | |

| Group (Late vs. Early) | 0.79 | 0.15 | 4.09 | 0.77 | |

| Ethnicity (Non-Hispanic vs. Hispanic) |

0.33 | 0.09 | 1.21 | 0.09 | |

| HIV Duration | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.09 | 0.95 | |

| Recent VL (log10) | 1.27 | 0.86 | 1.87 | 0.23 | |

| Recent CD4+ | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.64 | |

| CD4+ Nadir | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.39 | |

Figure 1. Logistic Regression Analysis Showing Probability of Hearing Loss for HIV-infected patients in the Left Ear according to Age and Sex.

The probability of hearing loss (y-axis) among HIV-infected participants increased with increasing age (x-axis) and there is a sex effect with males (Red line) having worse hearing than females (Blue line) in the left ear (panel A). Shaded areas delimit the 95% confidence intervals. Hearing loss in the right ear shows a similar age dependence, however the sex difference was not significant (panel B).

Table 4 shows mean pure tone thresholds by SPME models for the control, HIV-early and HIV-late groups separated out by age in decades for left (Table 4A) and right ear (Table 4B). Analysis with the SPMEs revealed a significant difference in population mean estimate of pure-tone thresholds in the left ear (p=0.01) and the right ear (p=0.02) between HIV-late and HIV-uninfected controls with worse mean pure-tone thresholds in HIV-infected subjects in late stage of HIV disease.

Table 4. Population Estimates of Pure-tone (PT) from the SPME Model Fitting, Modelling Frequency Non-parametrically and Controlling for Age (in decades) and Gender.

| A. Left ear | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

|

Population Estimate

of Pure-tone Left Ear |

Frequency (Hz) | |||||||||

| 0.25k | 0.5k | 1k | 1.5k | 2k | 3k | 4k | 6k | 8k | ||

| below | CONTROL | 4.45 | 5.67 | 5.57 | 5.13 | 7.44 | 9.84 | 10.98 | 14.59 | 15.34 |

| 25 | EARLY | 6.23 | 7.45 | 7.36 | 6.91 | 9.23 | 11.62 | 12.76 | 16.37 | 17.12 |

| LATE | 6.90 | 8.12 | 8.03 | 7.58 | 9.90 | 12.29 | 13.43 | 17.04 | 17.79 | |

| 25-34 | CONTROL | 4.74 | 5.96 | 5.86 | 5.42 | 7.74 | 10.13 | 11.27 | 14.88 | 15.63 |

| EARLY | 6.52 | 7.75 | 7.65 | 7.20 | 9.52 | 11.92 | 13.05 | 16.66 | 17.41 | |

| LATE | 7.19 | 8.42 | 8.32 | 7.87 | 10.19 | 12.59 | 13.72 | 17.33 | 18.08 | |

| 35-44 | CONTROL | 7.70 | 8.92 | 8.82 | 8.38 | 10.70 | 13.09 | 14.23 | 17.84 | 18.59 |

| EARLY | 9.48 | 10.71 | 10.61 | 10.16 | 12.48 | 14.88 | 16.01 | 19.62 | 20.37 | |

| LATE | 10.15 | 11.38 | 11.28 | 10.83 | 13.15 | 15.55 | 16.68 | 20.29 | 21.04 | |

| 45-54 | CONTROL | 8.01 | 9.23 | 9.13 | 8.69 | 11.00 | 13.40 | 14.54 | 18.15 | 18.90 |

| EARLY | 9.79 | 11.01 | 10.92 | 10.47 | 12.79 | 15.18 | 16.32 | 19.93 | 20.68 | |

| LATE | 10.46 | 11.68 | 11.58 | 11.14 | 13.46 | 15.85 | 16.99 | 20.60 | 21.35 | |

| 55-64 | CONTROL | 10.45 | 11.67 | 11.57 | 11.12 | 13.44 | 15.84 | 16.97 | 20.58 | 21.33 |

| EARLY | 12.23 | 13.45 | 13.35 | 12.91 | 15.22 | 17.62 | 18.76 | 22.37 | 23.11 | |

| LATE | 12.90 | 14.12 | 14.02 | 13.58 | 15.89 | 18.29 | 19.43 | 23.04 | 23.78 | |

| 65 & over |

CONTROL | 17.39 | 18.61 | 18.51 | 18.07 | 20.38 | 22.78 | 23.92 | 27.53 | 28.28 |

| EARLY | 19.17 | 20.39 | 20.29 | 19.85 | 22.17 | 24.56 | 25.70 | 29.31 | 30.06 | |

| LATE | 19.84 | 21.06 | 20.96 | 20.52 | 22.84 | 25.23 | 26.37 | 29.98 | 30.73 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| B. Right ear | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| below | CONTROL | 6.12 | 7.13 | 7.14 | 6.57 | 8.02 | 10.42 | 10.56 | 14.51 | 16.36 |

| 25 | EARLY | 8.01 | 9.02 | 9.03 | 8.46 | 9.91 | 12.31 | 12.45 | 16.40 | 18.25 |

| LATE | 8.43 | 9.44 | 9.45 | 8.88 | 10.33 | 12.73 | 12.87 | 16.82 | 18.67 | |

| 25-34 | CONTROL | 5.45 | 6.46 | 6.47 | 5.90 | 7.35 | 9.75 | 9.89 | 13.84 | 15.69 |

| EARLY | 7.34 | 8.36 | 8.36 | 7.79 | 9.24 | 11.64 | 11.78 | 15.73 | 17.58 | |

| LATE | 7.76 | 8.77 | 8.78 | 8.21 | 9.66 | 12.06 | 12.20 | 16.15 | 18.00 | |

| 35-44 | CONTROL | 8.31 | 9.33 | 9.34 | 8.76 | 10.22 | 12.61 | 12.75 | 16.70 | 18.55 |

| EARLY | 10.20 | 11.22 | 11.23 | 10.66 | 12.11 | 14.51 | 14.65 | 18.60 | 20.45 | |

| LATE | 10.62 | 11.64 | 11.65 | 11.08 | 12.53 | 14.92 | 15.06 | 19.01 | 20.86 | |

| 45-54 | CONTROL | 8.77 | 9.78 | 9.79 | 9.22 | 10.67 | 13.07 | 13.21 | 17.16 | 19.01 |

| EARLY | 10.66 | 11.68 | 11.68 | 11.11 | 12.56 | 14.96 | 15.10 | 19.05 | 20.90 | |

| LATE | 11.08 | 12.09 | 12.10 | 11.53 | 12.98 | 15.38 | 15.52 | 19.47 | 21.32 | |

| 55-64 | CONTROL | 11.14 | 12.16 | 12.16 | 11.59 | 13.04 | 15.44 | 15.58 | 19.53 | 21.38 |

| EARLY | 13.03 | 14.05 | 14.06 | 13.49 | 14.94 | 17.34 | 17.48 | 21.42 | 23.28 | |

| LATE | 13.45 | 14.47 | 14.48 | 13.91 | 15.36 | 17.75 | 17.89 | 21.84 | 23.69 | |

| 65 & over |

CONTROL | 17.50 | 18.52 | 18.53 | 17.96 | 19.41 | 21.81 | 21.95 | 25.90 | 27.75 |

| EARLY | 19.40 | 20.41 | 20.42 | 19.85 | 21.30 | 23.70 | 23.84 | 27.79 | 29.64 | |

| LATE | 19.82 | 20.83 | 20.84 | 20.27 | 21.72 | 24.12 | 24.26 | 28.21 | 30.06 | |

Note: Significant group difference in PT was detected between CONTROL and HIV LATE: p=0.02, after CONTROLling for frequency non-parametrically and age in decades. Sex was dropped from the model by the likelihood ratio test (p=0.75).

There were no statistical significant differences among the three study groups in overall 4-PTA in either ear but males had marginally worse 4-PTA in the left ear compared to females (Table 5).

Table 5. Population Estimate of Pure-tone Controlling for Age (in decades) and Gender by ANOVA Analysis of 4-PTA.

|

Population Estimate of Pure-

tone controlling for other factors (S.E.) |

Group | Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Early | Late | Female | Male | |

| Left | 12.60 (0.74) |

14.01 (0.77) |

13.96 (0.72) |

12.67 (0.68) |

14.37 (0.57) |

| Right | 12.17 (0.76) |

14.00 (0.78) |

13.84 (0.74) |

12.88 (0.69) |

13.79 (0.59) |

Note: There were no statistical significant differences among the three study groups in overall 4-PTA. A gender difference in 4PTA of left ear was detected: p=0.04, with males having marginally worse 4-PTA in the left ear. S.E.= standard error

We conducted exploratory comparisons of individual frequency pure-tone thresholds between the study groups. These analyses showed that HIV-infected patients at late stage of disease had statistically significant poorer pure-tone thresholds in the lower frequencies [.25 kHz (adjusted p=0.04), .5 kHz (adjusted p=0.01) and 1 kHz (adjusted p=0.04)] in the left ear and for the .25 kHz frequency (adjusted p=0.01) in the right ear when compared to control subjects (Table 6). Males also had poorer pure-tone thresholds in the left ear in the higher frequencies (4 kHz (p<0.01), 6 kHz (p<0.01), 8 kHz (p<0.01) when compared to females (data not shown).

Table 6. Population Estimate of Pure-tone (PT) by ANOVA Analysis at Each frequency, Controlling for Age (in decades) and Gender.

| Population Estimate of Pure-tone controlling for other factors (S.E.) |

Frequency (Hz) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25k | 0.5k | 1k | 1.5k | 2k | 3k | 4k | 6k | 8k | ||

|

LEFT

EAR |

CONTROL | 8.75* (0.63) |

10.07* (0.66) |

10.13* (0.77) |

9.79 (0.88) |

12.79 (0.99) |

16.19 (1.17) |

17.39 (1.24) |

20.35 (1.33) |

21.45 (1.53) |

| EARLY | 10.03 (0.66) |

11.25 (0.68) |

11.71 (0.80) |

11.74 (0.92) |

14.97 (1.03) |

17.69 (1.22) |

18.08 (1.29) |

21.25 (1.38) |

20.72 (1.60) |

|

| LATE | 10.84* (0.62) |

12.66* (0.64) |

12.64* (0.75) |

11.56 (0.87) |

13.76 (0.97) |

16.24 (1.15) |

16.79 (1.21) |

19.23 (1.31) |

19.16 (1.50) |

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

RIGHT

EAR |

CONTROL | 9.05* (0.64) |

10.70 (0.71) |

11.02 (0.78) |

10.22 (0.89) |

12.51 (1.00) |

14.13 (1.00) |

14.43 (1.23) |

18.04 (1.34) |

20.60 (1.62) |

| EARLY | 10.77 (0.66) |

12.44 (0.73) |

12.78 (0.80) |

11.49 (0.92) |

13.96 (1.03) |

16.82 (1.03) |

16.83 (1.27) |

18.86 (1.39) |

19.46 (1.69) |

|

| LATE | 11.53* (0.62) |

12.37 (0.69) |

13.11 (0.76) |

12.06 (0.87) |

14.07 (0.98) |

15.82 (0.98) |

15.81 (1.20) |

18.30 (1.32) |

18.88 (1.59) |

|

Note: After controlling for age in decades and gender, significant group difference in PT was detected in left ear at following frequencies: at 0.25k, control vs. HIV late: p=0.04; at 0.5k, control vs. HIV late: p=0.01; at 1k, control vs. HIV late: p=0.04. Significant group difference in PT was also detected in right ear at 0.25k, control vs. HIV late: p=0.01.

The application of three-way ANOVA (shown in Table 7) revealed significant differences in WRS in the right ear among groups (p=0.02), a significant group effect on tympanogram static admittance in both the left (p<0.01) and right ears (p=0.03), and a significant group effect on tympanic gradient in the right ear (p=0.03); while there were no differences in noise exposure by recreational activity among groups. Sex affected tympanogram static admittance in both the left (p=0.02) and right ears (p=0.02). In both cases the males had larger static admittance than the females, and males had more noise exposure by recreational activity (p<0.01).

Table 7. Population Estimates of Word Recognition Scores, Tympanometry, and Recreational Noise Exposure by Three-Way ANOVA.

| Effect | Group / Sex | Estimate | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | C.I. | |||

| Word Recognition Score (Left) | CONTROL | 98.50 | (97.80, 99.19) | 0.11 |

| EARLY | 98.05 | (97.33, 98.77) | ||

| LATE | 97.51 | (96.83, 98.19) | ||

| Word Recognition Score (Right) | CONTROL | 98.46 | (97.73, 99.18) | 0.02 |

| EARLY | 98.26 | (97.52, 99.01) | ||

| LATE | 97.22 | (96.51, 97.92) | ||

| *Tympanic Admittance (Left) | CONTROL | 0.89 | (0.79, 1.01) | <0.01 |

| EARLY | 0.81 | (0.72, 0.92) | ||

| LATE | 0.68 | (0.60, 0.77) | ||

| *Tympanic Admittance (Left) | FEMALE | 0.73 | (0.65, 0.82) | 0.02 |

| MALE | 0.85 | (0.78, 0.94) | ||

| *Tympanic Admittance (Right) | CONTROL | 0.84 | (0.75, 0.95) | 0.03 |

| EARLY | 0.82 | (0.73, 0.93) | ||

| LATE | 0.70 | (0.62, 0.79) | ||

| *Tympanic Admittance (Right) | FEMALE | 0.72 | (0.65, 0.81) | 0.02 |

| MALE | 0.85 | (0.77, 0.94) | ||

| Tympanic Gradient (Left) | CONTROL | 92.64 | (83.66, 101.63) | 0.49 |

| EARLY | 86.95 | (77.60, 96.30) | ||

| LATE | 85.40 | (76.36, 94.44) | ||

| Tympanic Gradient (Right) | CONTROL | 101.10 | (89.87, 112.33) | 0.03 |

| EARLY | 89.91 | (78.18, 101.64) | ||

| LATE | 80.28 | (68.95, 91.61) | ||

| Recreational activity | CONTROL | 17.20 | (15.70, 18.70) | 0.24 |

| EARLY | 16.94 | (15.37, 18.52) | ||

| LATE | 15.61 | (14.07, 17.15) | ||

| Recreational activity | FEMALE | 14.42 | (12.99, 15.85) | <0.01 |

| MALE | 18.75 | (17.58, 19.93) | ||

Note:

ANOVA was applied to transformed data. Estimates and Confidence Intervals (C.I.) for these transformed variables were back transformed to the original units.

Further pairwise comparisons indicated that WRS in the right ear were higher in the control group than in HIV-infected participants at late stage of disease (adjusted p=0.03) and the static admittance was larger in the control group as compared to the HIV-infected group at late stage of disease, for the left ear (adjusted p<0.01), data not shown. In addition, there was also a significantly larger gradient in controls as compared to the HIV-infected group at late stage of disease (adjusted p=0.02). There was also a significant effect of age on WRS with higher scores in younger subjects as compared to older subjects regardless of subject group (infected or non-infected subjects) in both left ear (p=0.02) and right ear (p<0.01), data not shown.

Older participants were more likely to have work related noise exposure (p=0.03) and the work noise exposure was greater as the participants’ age increased (p= 0.02) regardless of group. Males were more likely to have work related noise exposure (p<0.01) and the work noise exposure was greater as males’ age increased (p<0.01), data not shown. Moreover, a significant sex effect was found for recreational noise exposure with males having significantly greater exposure to potentially harmful noise (p<0.01); men were 2.6 times more likely to have been exposed to firearms [Odds Ratio= 2.6; C.I. = (1.6, 4.3)], data not shown.

Discussion

Small studies and case reports have described hearing loss in patients with HIV/AIDS. However, previous reports in the literature have been inconsistent in their findings, have not always excluded opportunistic infections of the central nervous system or noise exposure and have not included HIV-uninfected controls, potentially complicating their interpretation. Some case reports have attributed changes of hearing function to medication toxicity, as mitochondrial toxicity is a known effect of some ARV medications and damaged mitochondrial DNA may lead to problems with neural functioning in the inner ear. Mitochondrial dysfunction may also contribute to cellular aging, either by the release of potentially harmful reactive oxygen species (Kujoth 2005) or by directly activating tumor suppressor pathways, leading to apoptosis or cellular senescence and the inability to maintain tissue homeostasis. Current regimens are generally easier to administer, safe, and better tolerated so it is unclear if the newer ARV medications would have the same effect.

Despite the undeniable beneficial effect of HAART on mortality, long-term treated HIV-infected persons have an expected life span that is substantially shorter than that of their HIV-uninfected peers (Deeks 2012). This shortened life span is largely due to an increased risk of a number of “non-AIDS” complications, including heart disease, cancer, liver disease, kidney disease, bone disease, and neurocognitive decline. Many of these complications are similar to those observed among the elderly raising concerns that HIV-infected persons may be experiencing accelerated or “premature aging.” Age related hearing loss is a well-recognized entity (Gates & Mills 2005) and one possible explanation involves the accumulation of genetic mutations in mitochondrial DNA (Pickles 2004). Damaged mitochondrial DNA may cause reduced oxidative phosphorylation, which may lead to problems with neural functioning in the inner ear leading to narrowing of the vasa nervorum or a greater rate of apoptosis.

In this cross sectional analysis we found, using a pure-tone average over 4 frequencies, a sensorineural hearing loss prevalence of 17.6% in the cohort of HIV-infected subjects. We found that age at baseline was significantly different among those HIV-infected individuals with hearing loss compared to those with normal hearing (54.4 vs. 44.9 years, p<0.01), which is consistent with aging being the primary risk factor for hearing loss in HIV-infected subjects, as it is in the general population. However, nadir CD4+ cell count and duration of HIV infection were also significantly different between those HIV-infected individuals with hearing loss and those without but HIV disease stage was not; and elevated thresholds were noted in both early and late stage HIV disease.

Consistent with self-reports of hearing difficulty, word recognition scores were better for controls compared to HIV-infected individuals at late stage of disease. However, these scores were good in all groups and the difference was relatively small and may not be clinically significant.

Interestingly, in exploratory analyses of pure-tone thresholds by individual frequencies, hearing loss in our study cohort was evident at lower frequencies, with HIV-infected participants having better hearing at high frequencies compared to the control group. These findings are not typical of age related hearing loss and may be the result of a middle ear effect rather than a sensory-neural phenomenon. Moreover, the reduced static admittance in the later stage HIV-infected subjects may suggest subclinical middle-ear pathology in HIV disease; however, this difference is very small. Although the admittance was reduced in individuals in the later stage HIV-infected subjects, the tympanometric peaks were broader in control subjects. The etiology of these findings is uncertain but may indicate changes in the middle ear function. Extra caution was taken to eliminate any subjects who had significant air-bone gaps or conductive hearing loss. Whether these changes are secondary to HIV disease itself, toxicity from medications, persistent inflammation or a combination of factors is presently unclear. The fact that the HIV-infected patients had better hearing at high frequencies compared to the controls is difficult to explain but it could be due to a self-selection bias on the part of the control subjects. These healthy individuals may have agreed to participation in the study to obtain a hearing test to confirm their suspicion of having a problem.

Notably, longer duration of HIV disease and lower CD4+ cell count nadir were associated, in this study, with hearing loss; the smaller numbers may explain why this association was not confirmed by Logistic Regression Analysis. Severely impaired immune function may be indicative of worse inflammation and immune activation affecting hearing function or may indicate a direct role for the immune system on hearing function. Changes in hearing function in HIV-infection may occur as a result of the viral infection early in the course of the illness or could represent either cumulative exposure to medication toxicity or long term inflammation. Figure 1 illustrates that clinically significant hearing loss is rare for HIV patients younger than 40, but ubiquitous for those older than 60. Although our results may not indicate premature aging, given the increase survival in the HIV-infected patients, clinicians will increasingly encounter patients with hearing difficulties in this population and different strategies may be needed to ensure optimal communication with these older patients (Pacala & Yueh 2012; Lin 2012).

Our study includes a 4-year follow-up which will be instrumental in assessing progression of hearing function as well as the impact of ARV medications on hearing function. Analyses of other parameters including indicators of inner ear pathology are important to elucidate the impact of neurological involvement which is known to persist despite ARV treatment.

Summary.

Persistent inflammation and immune activation despite viral suppression has been postulated as cause of “accelerated” aging in HIV-infected patients responsible for increase in morbidity. We conducted a prospective cross sectional analysis of hearing function in 300 patients with HIV-infection and found that hearing loss in HIV-infected subjects increase with increasing age similar to what is described in the general population. Interestingly, HIV-infected subjects had hearing loss in the low-frequencies as compared to the HIV uninfected controls. Middle ear function was also poorer in the HIV-infected subjects, and they tended to have slightly poorer word discrimination ability and were more likely to complain of hearing symptoms.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients for their commitment to the study; to Nurhan Calisir and Jane Reid for their assistance with data management; Carol Greisberger for her guidance in protocol development and regulatory affairs and to Cathy Garrett for initial volunteer recruitment.

Financial support: National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), National Institutes of Health (NIH; grant 1R01DC009395-01A2).

Supported in part by the University of Rochester Developmental Center for AIDS Research grant P30 AI078498 (NIH/NIAID) and the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry and by National Institutes of Health (NIH)–National Institute on Aging Grant R01-AG16319, NIH–National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) Grant P30-DC05409 (Center for Navigation and Communication Sciences), NIH-NIAID grant R01 AI 087135, and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01 HD071779-01A1.

References

- Bai U, Seidman MD, Hinojosa R, et al. Mitochondrial DNA deletions associated with aging and possibly presbycusis: a human archival temporal bone study. Am J Otol. 1997 Jul;18(4):449–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeyer, Gregory Au.D., OSHA [Accessed September 2009];Recordable Questionnaire from the Adventist Medical Center at Portland, OR. http://www.adventisthealthnw.com/services-and-programs/audiology-forms.

- Dai P, Yang W, Jiang S, et al. Correlation of cochlear blood supply with mitochondrial DNA common deletion in presbyacusis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004 Mar;124(2):130–6. doi: 10.1080/00016480410016586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks SG, Verdin E, McCune JM. Immunosenescence and HIV. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012 Aug;24(4):501–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Landay A. Early immune senescence in HIV disease. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010 Feb;7(1):4–10. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0038-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GA, Mills JH. Presbycusis. Lancet. 2005 Sep 24-30;366(9491):1111–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CW, Cokely CG, Schupbach J, et al. Neurootologic findings of a patient with Acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Case Report. Ear and Hearing. 1989;10(1):68–76. doi: 10.1097/00003446-198902000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy RM, Bredesen DE, Rosenblum ML. Neurological manifestations of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): experience at UCSF and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1985 Apr;62(4):475–95. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.4.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H, et al. Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Morbidity and aging in HIV-infected persons: the Swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Dec;53(11):1130–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujoth GC, Hiona A, Pugh TD, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science. 2005 Jul 15;309(5733):481–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1112125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis W, Dalakas MC. Mitochondrial toxicity of antiviral drugs. Nat Med. 1995;1:417–422. doi: 10.1038/nm0595-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin FR. Hearing Loss in Older Adults. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1147–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markaryan A, Nelson EG, Hinojosa R. Quantification of the mitochondrial DNA common deletion in presbycusis. Laryngoscope. 2009 Jun;119(6):1184–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.20218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra CM, Wechkin HA, Longstreth WT, Jr, et al. Hearing loss and ARVT in patients infected with HIV-1. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:407–410. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160049015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez OP, French MA. Acoustic neuropathy associated with zalcitabine-induced peripheral neuropathy. AIDS. 1993;7(6):901–2. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199306000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata Castro N, Yebra Bango M, Tutor de Ureta P, et al. Hipoacusia e infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana. Estudio de 30 pacientes. Rev Clin Esp. 2000;200:271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte S, Fenwick JD, Monteiro EF. Irreversible ototoxicity associated with zalcitabine. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8(3):201–2. doi: 10.1258/0956462971919723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash SD, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein R, et al. The prevalence of hearing Impairment and associated risk factors: The Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Arch Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg. 2011:137–432. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) NIH [Accessed September 10, 2012];1997 Oct; http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/hearing/pages/presbycusis.aspx. NIH Pub. No. 97-4235.

- Pacala J, Yueh B. Hearing Deficits in the Older Patient “I Didn’t Notice Anything.”. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1185–1194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles JO. Mutation in mitochondrial DNA as a cause of presbyacusis. Audiol Neurootol. 2004 Jan-Feb;9(1):23–33. doi: 10.1159/000074184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucek S, Michaels L. the ear in the Acquired immune deficiency syndrome: II. Clinical and Audiologic investigation. The American Journal of Otology. 1996;17:35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]