Abstract

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a very common pathology. Its most common diagnosis is idiopathic. Although it is accepted that chronic increase in pressure within the carpal tunnel is responsible for median nerve neuropathy, the exact pathophysiology leading to this pressure increase remains unknown. All the histological studies of the carpal tunnel in the CTS find a noninflammatory thickening of the subsynovial connective tissue (SSCT), which seems to be a characteristic of this pathology. Numerous animal models have been developed to recreate CTS in vivo to develop and improve preventive strategies and effective conservative treatments by a better understanding of its pathophysiology. The creation of a shear injury of the SSCT in a rabbit model induced similar modifications to what is observed in CTS, suggesting that this could be a pathway leading to idiopathic CTS.

Keywords: carpal tunnel, subsynovial connective tissue, animal models

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a very common pathology that can be secondary to a great number of conditions.1 2 3 However, the most common diagnosis for CTS is idiopathic. It is accepted that chronic increase in pressure within the carpal tunnel is responsible for median nerve ischemia and subsequent segmental demyelination,4 5 but the exact pathophysiology leading to this pressure increase remains unknown.

When conservative treatment has failed, surgical division of the carpal transverse ligament (CTL) is considered. However surgical treatment gives excellent results in only 75% of the cases, leaving the remaining 25% with less satisfactory results.6

Understanding the exact pathway leading to CTS by creating accurate animal models could result in the development of new therapeutic and preventive strategies.

Carpal Tunnel SSCT

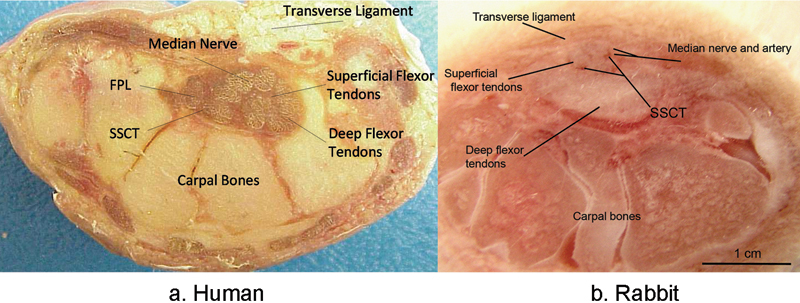

The carpal tunnel is a confined anatomic space bounded by the carpal bones on the dorsal, medial, and lateral sides and the flexor retinaculum on the palmar side, in which nine flexor tendons and the median nerve are enveloped by the subsynovial connective tissue (SSCT) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

(a) Carpal tunnel anatomy; (b) transverse cut section of the carpal tunnel through the hamate. (Fig. 1 right modified from Ettema et al, Clin Anat 2007;20(3):292–299.)

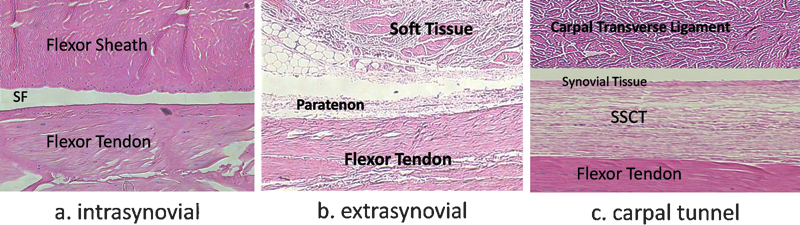

Flexor tendons can be separated in two different types: intra- or extrasynovial. These behave differently in regards to gliding and healing properties.7 Intrasynovial tendons lie in a synovial fluid environment limited by a parietal and visceral synovium layer.8 These tendons are therefore less vascularized, because only two vinculas supply the dorsal portion of the flexor tendons and because the volar side relies on synovial fluid diffusion for nutrient supplies.9 Extrasynovial tendons, on the other hand, are nourished by a surrounding and richly vascularized loose paratenon.7 However, inside the carpal tunnel the flexor tendons are neither totally intra- nor extrasynovial (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Structure of the flexor tendon; (a) zone II, (b) zone III, (c) zone IV; SF: synovial fluid, SSCT: subsynovial connective tissue. (H&E original magnification x 400; (Fig. 2c modified from Ettema et al, Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;118(6):1413–1422.)

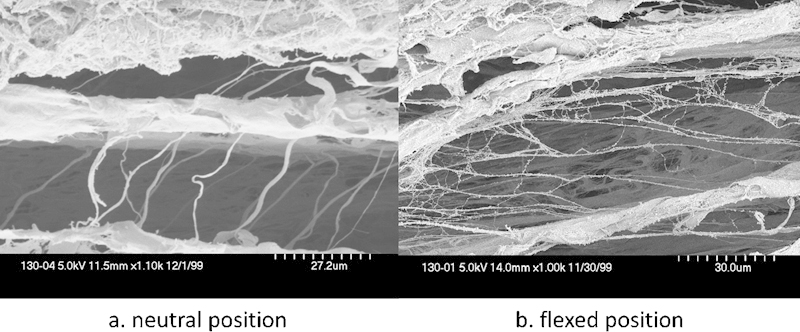

The carpal tunnel contains two bursae: radial and ulnar. The radial bursa envelopes only the flexor pollicis longus. All the other flexor tendons are enveloped by the ulnar bursa. The visceral synovium of this bursa is separated from the flexor tendons by a loose areolar tissue called the microvacuolar collagenous dynamic absorbing system, abbreviated MVCAS. This tissue was described in 2001 by Guimberteau10 based on endoscopic, microscopic, and macroscopic findings both in vitro and in vivo. The MVCAS is a continuous organized collagenous structure that surrounds the flexor tendons in zones III, IV and V, facilitating their sliding and providing a scaffold for the surrounding vascular elements (Fig. 3). It also has a biomechanical function in absorbing and transmitting stress.11 It is mainly composed of type VI collagen fibers (Fig. 4).12 Because the MVCAS in the carpal tunnel is surrounded by the visceral synovium of the ulnar bursa, it is known as the subsynovial connective tissue (SSCT). This hybrid combination of intrasynovial and MVCAS surrounding makes the flexor tendons inside the carpal tunnel unique, allowing them to have gliding properties with both a viscoelastic and a synovial fluid lubrication component.13

Fig. 3.

Vertical fibers between different layers in the SSCT are loose (a) in neutral position and (b) become stretched as the tendon slides. (SEM original magnification, a: x1.10k b: x1.00k.) (Both images are from Ettema et al, Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;118(6):1413–1422.)

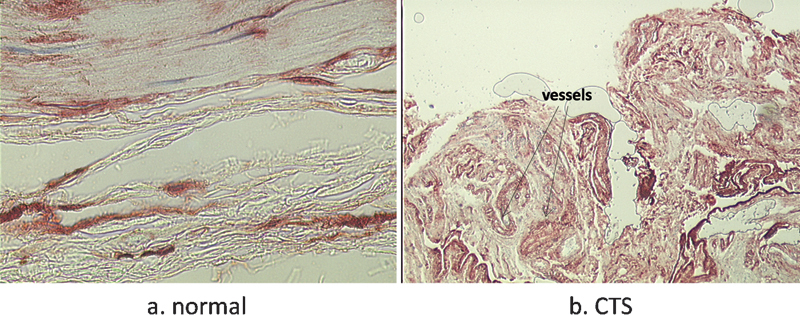

Fig. 4.

Collagen type VI staining (a) in normal and (b) CTS SSCT. Fibrosis and increased vascularization are observed in CTS.

Pathological Changes in the Carpal Tunnel SSCT

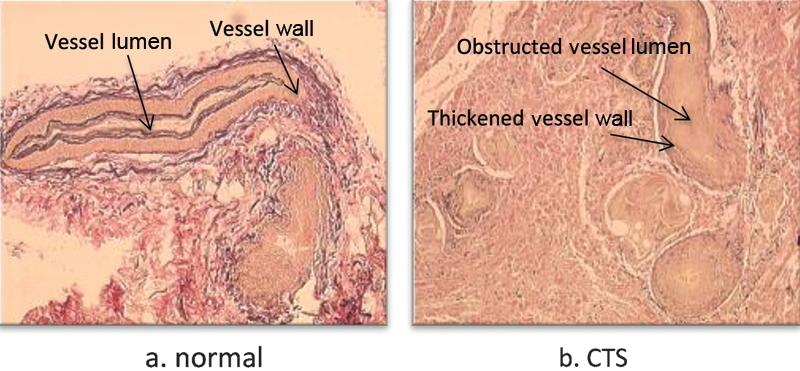

All the histological studies of the carpal tunnel in the CTS find a noninflammatory thickening of the SSCT which seems to be a characteristic of this pathology.12 14 15 16 This thickening might increase the volume and pressure in the carpal tunnel and also decrease the SSCT permeability, resulting in a tenosynovial ischemia and reperfusion (Fig. 5).17 But whether this fibrosis is the cause or the consequence of the CTS is unknown, and so is its exact progression. More thorough studies of the SSCT have been performed to find elements that would help answering this question.

Fig. 5.

Elastin staining (Verhoeff-Van Gieson method) (a) of normal and (b) pathologic SSCT, shows an increased number of vessels, with an obstructed lumen and a thickened wall in CTS. (Fig. 5b modified from Oh et al, J Orthop Res 2004;22(6):1310–1315.)

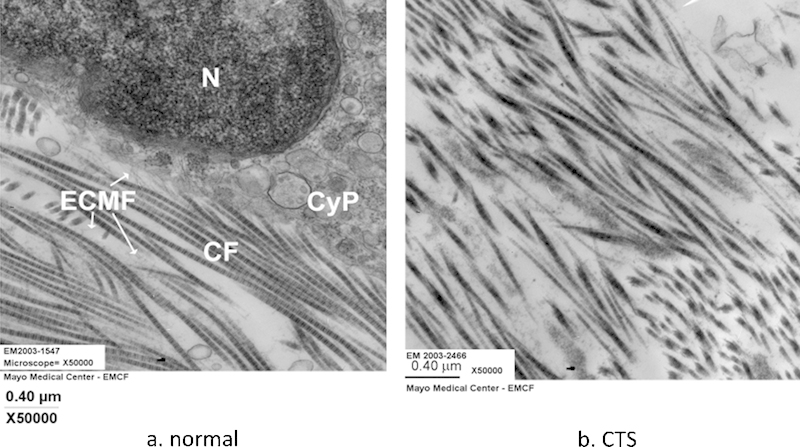

In 2004, Ettema et al12 found a modification in the distribution and size of collagen fibers in pathologic carpal tunnel SSCT, with an increased quantity of type III collagen fibers and an increased diameter of those fibers. This was confirmed by Oh et al18 who found using transmission electron microscopy not only that the collagen fibrils were thickened in SSCT but also that their ultrastructural morphology was modified compared with normal SSCT collagen fibrils.

Fibrosis Models

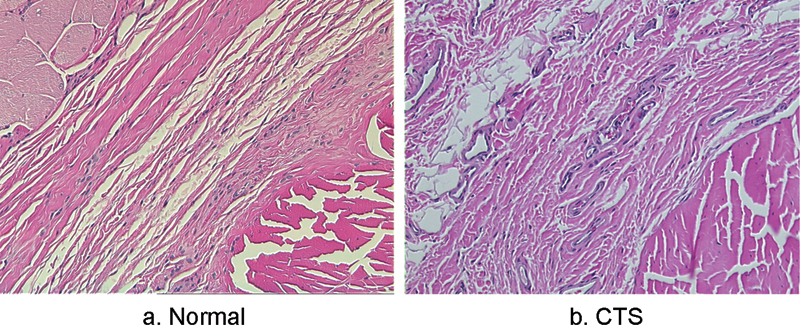

Plenty of models have been developed to study the effect of the increase in pressure on the median nerve by increasing the volume of carpal tunnel contents using saline19 or angioplasty catheters5; others have tried to decrease the size of the carpal tunnel by tightening the carpal transverse ligament.20 Although these animal models provide knowledge of the association of median nerve tolerance to the pressure, they do not mimic the true pathological condition of the CTS and do not explain how this compression is generated or maintained. Because the carpal tunnel SSCT appears to play a major role in the pathophysiology of the CTS, it is important to develop a model that would take into account the pathological changes observed in the SSCT in the CTS. Ettema et al studied several animal carpal tunnels, focusing on the structure of the SSCT compared with humans. They found that rabbit SSCT had a similar micro- and macrostructure compared with human SSCT (Fig. 6).21 However, Tung et al found the compliance of rabbit carpal tunnel to be much higher than that of human carpal tunnel.22 Yamaguchi et al23 described a way to measure SSCT material properties in rabbits, making rabbits a good option as an animal model of CTS. To understand the gradual pathway leading to median nerve neuropathy in CTS, the authors attempted to recreate experimentally a noninflammatory fibrosis of the SSCT on an in vivo rabbit model. This has been done successfully by repeated glucose injections in rabbits' carpal tunnels (Fig. 7).24 25 26 27 28 Multiple glucose injections indeed led to SSCT fibrosis and nerve histological and electrophysiological changes consistent with neuropathy. However, it is impossible to know whether these changes were caused by the fibrosis or by the osmotic effect on the median nerve of the hypertonic glucose. To improve this model, new solutions have been tried, based on the microtear hypothesis.

Fig. 6.

Cross section of the carpal tunnel (a) in the human and (b) the rabbit. (Both images are from Ettema et al, Hand (N Y) 2006;1(2):78–84.)

Fig. 7.

Histology slides (H&E) of SSCT (a) in normal carpal tunnel and (b) after repeated glucose injections. After glucose injection the connective tissue proliferated and the SSCT fibers became thicker and irregular.

Microtear Hypothesis

It is widely accepted that repetitive motion of the wrist, hand, and fingers can lead to idiopathic CTS, but again, the precise chain of events between these two conditions in not well established, and numerous studies have tried to clarify this pathway. Ettema et al15 found that the more severe changes in the SSCT in the CTS were observed around the flexor tendons, suggesting that repetitive motion of the tendons could lead to a modification of their surrounding SSCT. This seems to be confirmed by the findings of Zhao et al,13 who found on cadaveric specimens that finger motion created important friction forces on the SSCT, especially when the wrist was flexed. Moreover, they proved that differential finger motion led to an increase in gliding resistance. This could result in a shear injury of the SSCT,29 because the normal SSCT has been proved to be able to withstand only relatively low loads before failure.30 Therefore, differential digit flexion could result in a shear strain sufficient to injure the SSCT, triggering a wound-healing process as the increased amount of TGF-β found in CTS SSCTs would tend to indicate (Fig. 8).12 These results were corroborated by a rabbit in vivo study in which physiological excursion of the third flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) tendon provoked collagen fibril ruptures in the SSCT.31

Fig. 8.

Immunohistochemistry staining of the SSCT (a) in a normal and (b) pathologic carpal tunnel. The expression of TGF-β receptor is increased in patients with CTS. (Arrows show positive staining.)

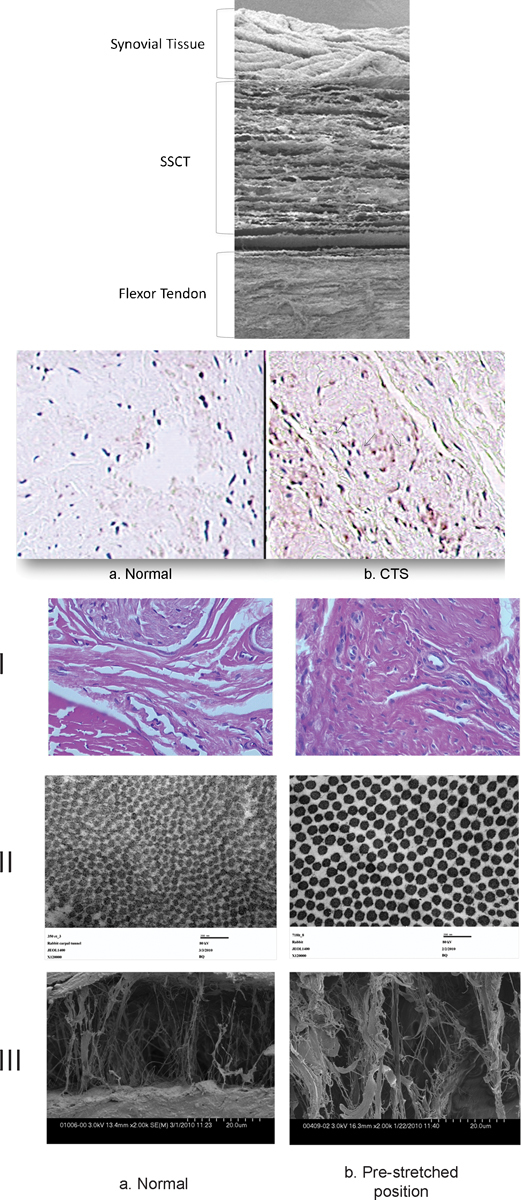

Based on this hypothesis, a rabbit in vivo model was developed.32 The goal of this model was to fix the FDS tendon in a stretched position, which would in turn stretch the surrounding SSCT, predisposing it to shear injuries. Twelve weeks after the surgery, histological and eletrophysiological findings of the SSCT and of the median nerve proved themselves to be similar to what is observed in CTS (Fig. 9). The success of this animal model strengthens the hypothesis that SSCT shear injury is the first event leading ultimately to CTS.

Fig. 9.

Light microscopy, H&E staining (line I), transmission electron microscopy (line II) and scanning electron microscopy (line III) of the SSCT in normal rabbit carpal tunnel (a column) and in the prestretched model (b column) show similar modifications in the prestretched group (higher fibroblast density (bI), thicker collagen fibers (bII), and thicker collagen bundles (bIII)) to what is observed in CTS. (Figure 9 row 1, row 2, and row 3 modified from Moriya et al, Hand (N Y) 2011;6(4):399–407.)

Conclusion

Carpal tunnel syndrome is a significant clinical problem. It is the most common compression neuropathy, with an incidence of 3.8% in the general population.33 This incidence is increasing at an accelerating rate, and more severe forms are found in older patients, which could be a concern as the population is aging.34 However, the precise etiology of CTS remains unknown, but a better understanding of the causes of this entrapment neuropathy appears to be crucial to develop new therapies. Indeed, although many hypotheses have been put forward, no preventive strategy has proven to be efficient, and conservative treatments such as local corticosteroid injections or splinting do not provide a clinical improvement lasting more than a month.35 Developing new animal models that could accurately mimic the pathway leading to CTS could enable development and improvement of preventive strategies and effective conservative treatments.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by a grant from NIH/NIAMS (AR49823).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None

References

- 1.Katz J N, Simmons B P. Clinical practice. Carpal tunnel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(23):1807–1812. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp013018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka S, Wild D K, Seligman P J, Behrens V, Cameron L, Putz-Anderson V. The US prevalence of self-reported carpal tunnel syndrome: 1988 National Health Interview Survey data. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(11):1846–1848. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Krom M C, Kester A D, Knipschild P G, Spaans F. Risk factors for carpal tunnel syndrome. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(6):1102–1110. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelberman R H, Rydevik B L, Pess G M, Szabo R M, Lundborg G. Carpal tunnel syndrome. A scientific basis for clinical care. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19(1):115–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diao E, Shao F, Liebenberg E, Rempel D, Lotz J C. Carpal tunnel pressure alters median nerve function in a dose-dependent manner: a rabbit model for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Orthop Res. 2005;23(1):218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bland J DP. Carpal tunnel syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18(5):581–585. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000173142.58068.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelberman R H, Seiler J G III, Rosenberg A E, Heyman P, Amiel D. Intercalary flexor tendon grafts. A morphological study of intrasynovial and extrasynovial donor tendons. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1992;26(3):257–264. doi: 10.3109/02844319209015268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen M J, Kaplan L. Histology and ultrastructure of the human flexor tendon sheath. J Hand Surg Am. 1987;12(1):25–29. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(87)80155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundborg G, Rank F. Experimental intrinsic healing of flexor tendons based upon synovial fluid nutrition. J Hand Surg Am. 1978;3(1):21–31. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(78)80114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guimberteau J C. Pessac, France: Aquitaine Domaine Forestier; 2001. How is the anatomy adopted for tendon sliding? In New Ideas in Hand Flexor Tendon Surgery: The Sliding System, Vascularized Flexor Tendon Transfers; pp. 47–90. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guimberteau J C, Delage J P, Wong J. The role and mechanical behavior of the connective tissue in tendon sliding. Chir Main. 2010;29(3):155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ettema A M, Amadio P C, Zhao C, Wold L E, An K N. A histological and immunohistochemical study of the subsynovial connective tissue in idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(7):1458–1466. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao C, Ettema A M, Osamura N, Berglund L J, An K-N, Amadio P C. Gliding characteristics between flexor tendons and surrounding tissues in the carpal tunnel: a biomechanical cadaver study. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(2):185–190. doi: 10.1002/jor.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr C D, Sybert D R, Albarracin N S. An analysis of the flexor synovium in idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome: report of 625 cases. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(6):1028–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(09)91053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ettema A M, Amadio P C, Zhao C. et al. Changes in the functional structure of the tenosynovium in idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome: a scanning electron microscope study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(6):1413–1422. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000239593.55293.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neal N C, McManners J, Stirling G A. Pathology of the flexor tendon sheath in the spontaneous carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg [Br] 1987;12(2):229–232. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681_87_90020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jinrok O, Zhao C, Amadio P C, An K N, Zobitz M E, Wold L E. Vascular pathologic changes in the flexor tenosynovium (subsynovial connective tissue) in idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome. J Orthop Res. 2004;22(6):1310–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh J, Zhao C, Zobitz M E, Wold L E, An K N, Amadio P C. Morphological changes of collagen fibrils in the subsynovial connective tissue in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(4):824–831. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim J Y, Cho S H, Han T R, Paik N J. Dose-responsiveness of electrophysiologic change in a new model of acute carpal tunnel syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(427):120–126. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000142352.88039.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lluch A L. Thickening of the synovium of the digital flexor tendons: cause or consequence of the carpal tunnel syndrome? J Hand Surg [Br] 1992;17(2):209–212. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(92)90091-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ettema A M, Zhao C, An K-N, Amadio P C. Comparative anatomy of the subsynovial connective tissue in the carpal tunnel of the rat, rabbit, dog, baboon, and human. Hand (NY) 2006;1(2):78–84. doi: 10.1007/s11552-006-9009-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tung W-L, Zhao C, Yoshii Y, Su F-C, An K-N, Amadio P C. Comparative study of carpal tunnel compliance in the human, dog, rabbit, and rat. J Orthop Res. 2010;28(5):652–656. doi: 10.1002/jor.21037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi T, Osamura N, Zhao C, Zobitz M E, An K-N, Amadio P C. The mechanical properties of the rabbit carpal tunnel subsynovial connective tissue. J Biomech. 2008;41(16):3519–3522. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oh S, Ettema A M, Zhao C. et al. Dextrose-induced subsynovial connective tissue fibrosis in the rabbit carpal tunnel: A potential model to study carpal tunnel syndrome? Hand (NY) 2008;3(1):34–40. doi: 10.1007/s11552-007-9058-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshii Y, Zhao C, Zhao K D, Zobitz M E, An K-N, Amadio P C. The effect of wrist position on the relative motion of tendon, nerve, and subsynovial connective tissue within the carpal tunnel in a human cadaver model. J Orthop Res. 2008;26(8):1153–1158. doi: 10.1002/jor.20640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshii Y, Zhao C, Schmelzer J D, Low P A, An K-N, Amadio P C. The effects of hypertonic dextrose injection on connective tissue and nerve conduction through the rabbit carpal tunnel. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(2):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshii Y, Zhao C, Schmelzer J D, Low P A, An K-N, Amadio P C. Effects of hypertonic dextrose injections in the rabbit carpal tunnel. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(7):1022–1027. doi: 10.1002/jor.21297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshii Y, Zhao C, Schmelzer J D, Low P A, An K-N, Amadio P C. Effects of multiple injections of hypertonic dextrose in the rabbit carpal tunnel: a potential model of carpal tunnel syndrome development. Hand (NY) 2014;9(1):52–57. doi: 10.1007/s11552-013-9599-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshii Y, Zhao C, Henderson J, Zhao K D, An K N, Amadio P C. Shear strain and motion of the subsynovial connective tissue and median nerve during single-digit motion. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osamura N, Zhao C, Zobitz M E, An K-N, Amadio P C. Evaluation of the material properties of the subsynovial connective tissue in carpal tunnel syndrome. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2007;22(9):999–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morizaki Y, Vanhees M, Thoreson A R. et al. The response of the rabbit subsynovial connective tissue to a stress-relaxation test. J Orthop Res. 2012;30(3):443–447. doi: 10.1002/jor.21547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moriya T, Zhao C, Cha S S. et al. Tendon injury produces changes in SSCT and nerve physiology similar to carpal tunnel syndrome in an in vivo rabbit model. Hand (NY) 2011;6(4):399–407. doi: 10.1007/s11552-011-9356-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, Ornstein E, Ranstam J, Rosén I. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. JAMA. 1999;282(2):153–158. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gelfman R, Melton L J III, Yawn B P, Wollan P C, Amadio P C, Stevens J C. Long-term trends in carpal tunnel syndrome. Neurology. 2009;72(1):33–41. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000338533.88960.b9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall S, Tardif G, Ashworth N. Local corticosteroid injection for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD001554. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001554.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]