Abstract

Tumor microenvironment is an essential element in prostate cancer (PCA), offering unique opportunities for its prevention. Tumor microenvironment includes naïve fibroblasts that are recruited by nascent neoplastic lesion and altered into ‘cancer-associated fibroblasts’ (CAFs) that promote PCA. A better understanding and targeting of interaction between PCA cells and fibroblasts and inhibiting CAF phenotype through non-toxic agents are novel approaches to prevent PCA progression. One well-studied cancer chemopreventive agent is silibinin, and thus, we examined its efficacy against PCA cells-mediated differentiation of naïve fibroblasts into a myofibroblastic-phenotype similar to that found in CAFs. Silibinin’s direct inhibitory effect on the phenotype of CAFs derived directly from PCA patients was also assessed. Human prostate stromal cells (PrSCs) exposed to control conditioned media (CCM) from human PCA PC3 cells showed more invasiveness, with increased α-SMA (alpha-smooth muscle actin) and vimentin expression, and differentiation into a phenotype we identified in CAFs. Importantly, silibinin (at physiologically-achievable concentrations) inhibited α-SMA expression and invasiveness in differentiated fibroblasts and prostate CAFs directly, as well as indirectly by targeting PCA cells. The observed increase in α-SMA and CAF-like phenotype was transforming growth factor (TGF) β2 dependent, which was strongly inhibited by silibinin. Furthermore, induction of ±-SMA and CAF phenotype by CCM were also strongly inhibited by a TGFβ2-neutralizing antibody. The inhibitory effect of silibinin on TGFβ2 expression and CAF-like biomarkers was also observed in PC3 tumors. Together, these findings highlight the potential usefulness of silibinin in PCA prevention through targeting the CAF phenotype in the prostate tumor microenvironment.

Keywords: Chemoprevention, Prostate cancer, Tumor microenvironment, Cancer-associated fibroblast, Silibinin

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is a heterogeneous disease encompassing myriad components: genetic susceptibility in the host, the degree and nature of exposure to environmental insults, the accumulation of these insults both systemically and locally at a developing tumor, and finally, the interactions of the otherwise normal cells and tissues in close contact with the cancerous lesion [1–11]. This last set of interactions include the tumor microenvironment (TM) or stroma, the total sum of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, soluble signaling factors, and neighboring noncancerous cells that interface with a tumor [10–14]. TM is now recognized as an integral component to carcinogenesis that directly contributes to the development of malignancy [13–15]. Thus, targeting this array of interactions, which if left unchecked, serves to support a progressive cancerous lesion, is considered a promising translational cancer preventive strategy. While the development of such a preventive strategy is of obvious importance in the case of all cancers, it is doubly so for prostate cancer (PCA) because of the high burden of this disease.

In the United States, the health care costs for PCA management in 2010 alone were an estimated 11.85 billion dollars [16]. In fact, PCA is the most common cancer diagnosed in men, and despite major investment in early detection, remains the second leading cause of cancer-associated mortality. In 2013, there will be an estimated 238,590 new cases of PCA and an estimated 29,720 deaths [17]. The high mortality results partially from the fact that 3/4ths of patients diagnosed with metastatic disease die within 5 years [16]. Furthermore, while the elimination of a tumor is of primary concern, even in the face of successful treatment, there is a significant probability for disrupting the quality of life for the patient, ranging from incontinence to impotence which may persist for years [18,19]. Thus the development of novel early preventive measures remains a high priority. In pursuit of developing such interventions, research and clinical efforts to date have focused on the dysfunctional activity of cancerous cells in a tumor. Only recently recognized is the contribution of otherwise normal healthy cells interfacing with a developing tumor. In this regard, neighboring fibroblasts have been suggested as a key cellular component of the PCA stroma, and their activity promotes tumor growth, invasiveness, metastasis, and angiogenesis [10–12]. In fact, recent findings suggest that developing lesions directly act on nearby noncancerous stromal cells in a positive feedback loop to promote tumor development [20]. A potential mechanism by which this phenomenon may be sustained is through PCA cell secretion of transforming growth factor β-2 (TGFβ2), which has numerous tissue specific roles, but most relevant in this milieu, it signals the differentiation of normal fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, capable of remodeling the extracellular matrix and allowing cancer cells to infiltrate nearby tissues [21–23].Therefore, targeting TGFβ2 expression in PCA cells as well as the differentiation of normal fibroblasts into CAFs using non-toxic agents could be an attractive approach to prevent PCA progression.

Silibinin is a component of milk thistle (Silybum marianum; Asteraceae) seeds extract and extensively used as a hepatoprotective intervention in both acute and chronic ailments [24]. More recently, silibinin has shown broad spectrum efficacy against PCA. It disrupts important signaling pathways necessary for PCA progression [25–27], inhibits proliferation while inducing apoptosis in PCA cells [26,28,29], inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) reducing PCA cell migration, invasion, and metastasis [30–32], as well as angiogenesis [29]. However, silibinin’s potential to abrogate the interactions of PCA cells with stromal cells remains to be determined. To address this possibility, we first developed in vitro protocols to recapitulate the activation/ transformation of naïve fibroblasts by aggressive PCA cells. For these studies, normal human prostate stromal cells (PrSCs) were used as a model for naïve fibroblasts. We generated PCA cell conditioned media capable of altering the phenotype of PrSCs into a myofibroblastic one. In the current study, this phenotype was found to be similar to that of cancer associated fibroblasts (CAF) isolated from a resection of clinically confirmed PCA and thus was labeled a CAF-like phenotype. Parallel to this effort, we also examined if silibinin, whether through direct action on stromal cells or through indirect action altering PCA cell-conditioned media, could ameliorate this PCA-mediated differentiation of fibroblasts, and thus halt an important step for carcinogenesis. Finally, we examined the direct effect of silibinin on CAF cells in an effort to determine if fibroblasts that have already become constitutively active in an aggressive phenotype can be rescued by silibinin intervention. Herein, our findings indicate that in addition to its widely reported anti-PCA properties, silibinin also inhibits a more recently acknowledged avenue for cancer progression, namely cancer cell-mediated recruitment of stromal fibroblasts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and reagents

Human PCA PC3, DU-145, LNCaP and 22Rv1 cells were from ATCC. C4-2B cells were from ViroMed Laboratories. PCA cell lines were tested and authenticated by DNA profiling for polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) markers at University of Colorado Cancer Center DNA Sequencing & Analysis Core. RPMI 1640 media, other cell culture materials, TGFβ1 ELISA kit, and CAS-Block were from Invitrogen. PrSCs, SCGM, and Bullet-kits were from Lonza. Prostate CAFs were from a prostatectomy specimen removed at Wake Forest University [13]. Pathology of specimen was verified by two board-certified pathologists (AC and JS). No patient identifiers were retained and use of discarded tissue was not considered human subjects research by Wake Forest University IRB. DAPI and silibinin were from Sigma, IL-6 from Cell Signaling, and TGFβ1, TGFβ2, and goat IgG isotype control antibody were obtained from Gibco. TGFβ2 ELISA kit and TGFβ2-neutralizing antibody were obtained from R&D, antibodies to IL-6, α-SMA and FAP (fibroblast activation protein) from Abcam, antibody to vimentin and HRP conjugated streptavidin from Santa Cruz, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) peroxidase substrate kit from Vector Labs, biotinylated antibodies and mouse IgG's from DAKO, and transwell invasion chambers from BD Biosciences.

Cell culture and conditioned media

DU-145 and PC3 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% heat inactivated FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin G and 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulfate under standard conditions. LNCaP, C4-2B, and 22Rv1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin G and 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulfate. PrSCs were cultured in SCGM with Bullet-kits. Prostate CAF cells were cultured in MCDB105 medium with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin G and 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulfate. Silibinin stock was in DMSO, with equal DMSO (not to exceed 0.1%, v/v) in each treatment. TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 were activated by citric acid prior to use. PCA cells were incubated in media for 72 hrs, washed twice, followed by media supplemented with 0.5% serum for 48 hrs. This media was then collected as respective cell line control conditioned media (CCM). Similarly, silibinin conditioned media (SBCM) was collected from PCA cells incubated with 30, 60 or 90 µM silibinin for 72 hrs, washed twice, followed by media supplemented with 0.5% serum (without silibinin) for 48 hrs and labeled as SBCM30, SBCM60 and SBCM90.

Cell viability and immunoblotting

PrSCs (3 × 104 cells per well) were seeded and treated as indicated, and then cell number and cell death determined by Trypan blue using a haemocytometer [33]. Total cell lysates were prepared in non-denaturing lysis buffer and immunoblotting performed as described earlier [33]. Bands were scanned with Adobe Photoshop 6.0 and the mean density of each band was analyzed by the Scion Image program.

Confocal imaging

PrSCs were grown on cover slips and incubated in basal media, CCM in presence or absence of silibinin (30–90 µM doses), SBCM, TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 (1–10 ng/mL), and control or TGFβ2 neutralizing antibodies (0.4 µg/mL). Except where noted, cells were treated for 24 hrs, then fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde overnight at 4° C, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min and thereafter blocking was done under 5% serum condition. Cells were washed with PBS containing 0.2% Tween and incubated with anti-α-SMA antibody and DAPI for 30 min. Cell images were captured at 1500× magnification on a Nikon inverted confocal microscope using 688/405 nm laser wavelengths to detect α-SMA (green) and DAPI (blue) emissions, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Paraffin-embedded PC3 tumor tissue sections from a PC3 xenograft study [34] were used to determine the in vivo effect of silibinin administration on the levels of TGFβ2, α-SMA, vimentin and FAP by IHC as described before [34,35]. Briefly, sections were incubated with anti-TGFβ2 (15 µg/mL dilutions), anti-α-SMA (1:75 dilutions), anti-vimentin (1:75 dilutions), and anti-FAP (1:50 dilutions) antibodies, followed by a specific biotinylated secondary antibody (1:250 dilutions), and then conjugated HRP streptavidin and DAB working solution, and counterstained with hematoxylin. Stained sections were analyzed by Zeiss Axioscope 2 microscope and images captured by AxioCam MrC5 camera at 400× magnifications. Immunoreactivity (represented by brown staining) was scored as 0+ (no staining), 1+ (weak staining), 2+ (moderate staining), 3+ (strong staining), 4+ (very strong staining).

ELISA assays

For the quantification of TGFβ1, CCM as well as SBCM 30, 60, 90 were collected from PC3 cells as previously described in Methods. These samples were then processed and assayed according to the provided protocols in a TGFβ1 ELISA kit. Regression curves from known standards were used to quantify the resultant O.D.’s as concentrations of TGFβ1. For the quantification of TGFβ2, CCM and SBCM30, 60 and 90 were collected from LNCaP, 22Rv1, C4-2B, DU-145, and PC3 cells as described in Methods. These samples were then processed and assayed according to the provided protocols in a TGFβ2 ELISA kit. Regression curves from known standards were used to quantify the resultant O.D.’s as concentrations of TGFβ2.

Invasion assay

Invasion assay was performed using invasion chambers as per vendor’s protocol. Bottom chambers of Transwell were filled with SCGM with 5% FBS and top chambers were seeded with 50,000 PrSCs (previously treated as per desired conditions) per well in SCGM (with 0.5% FBS). After 18 hrs of incubation, cells on top surface of membrane (non-invasive cells) were scraped with a cotton swab and cells spreading on bottom sides of membrane (invasive cells) were fixed, stained, and mounted. Images were captured using Cannon Power Shot A640 camera on Zeiss inverted microscope and total number of invasive cells was counted and percentage of cell invasion was calculated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism software. Data was analyzed using t-test, one-way or two-way ANOVA (where appropriate) followed by Newman-Keuls or Bonferroni post-hoc tests respectively, and a statistically significant difference was considered to be at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Media conditioned by PCA cells has the capacity to induce a CAF-like phenotype in PrSCs

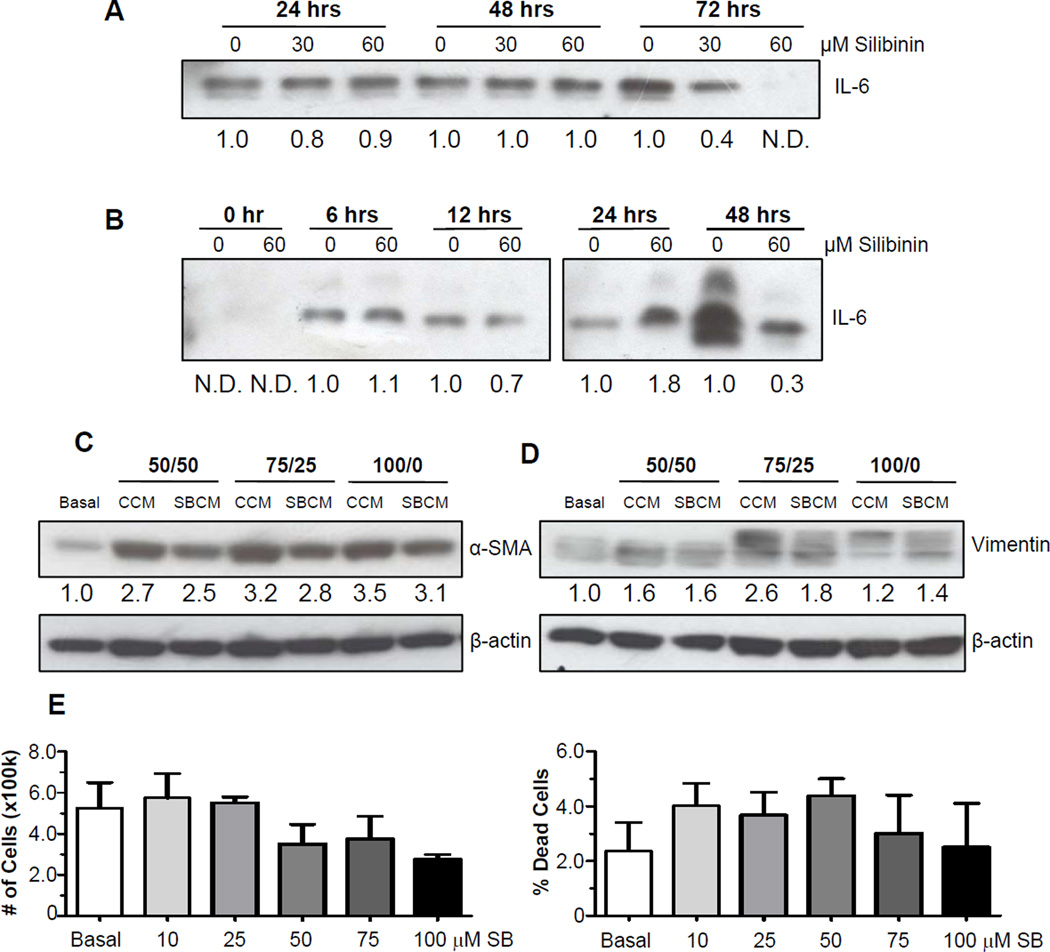

Experiments were undertaken to optimize both the protocols for conditioning media with PCA cells and for using this conditioned media to potently activate PrSCs. An additional criterion of interest was the capacity to assay the inhibition of this response by silibinin. Thus, media conditioned by PC3 cells in the absence and the presence of silibinin was denoted as control conditioned media (CCM) and silibinin conditioned media (SBCM), respectively. Based on the work of Giannoni et al [20], reporting that IL-6 secreted by PCA cells induces a CAF-like phenotype in naïve fibroblasts, we first focused on the accumulation of IL-6 in media as a measure of potency for conditioned media. Not surprisingly, data revealed that the concentration of IL-6 in media conditioned by PC3 cells increased over time (Figure 1A). It was also found that at 72 hrs, silibinin had the capacity to dose-dependently decrease IL-6 levels in PC3 conditioned media. Thus, future experiments were designed for 72 hrs incubation time (with or without silibinin) to produce conditioned media. Extensive reports have delineated the inhibitory effects of silibinin directly on PCA cells [25–32]. Thus, conditioned media collected from silibinin treated PC3 cells has the potential to directly inhibit the activation ofPrSCs. In addition, since high serum levels found in supplemented growth media may obfuscate both the activation and the inhibition of responses, we elected to follow the 72 hrs incubation period with multiple washes followed by incubation of PC3 cells with low serum (0.5%) growth media. This was designed to eliminate both contaminating silibinin as well as other activating agents found in growth media. Having identified the treatment time, we next sought to identify the time required for PC3 cells to effectively condition medium for further studies. IL-6 was not detectable in fresh low serum media, but was detectable after 6 hrs of conditioning (Figure 1B). PC3 cells treated with silibinin (60 µM) and then washed, exhibited a significant decrease in IL-6 levels by 48 hrs, and thus, this time was used in future studies as the time in which PC3 cells (treated or untreated with silibinin) would condition media to examine its effect on stromal cells. Having identified the parameters by which CCM/SBCM would be generated, we next sought to identify the concentration of CCM to PrSC media that would most potently activate PrSCs. We found that 100% CCM induced the expression of the CAF-like markers, α-smooth muscle actin (α–SMA) and vimentin, in PrSCs, which, compared to CCM, was reduced in SBCM-treated PrSCs (Figure 1C and 1D). Thus, 100% CCM and SBCM was used in all future experiments.

Figure 1.

Establishing the parameters for collecting PCA cell conditioned media and PrSC activation. (A) PC3 were treated with silibinin at the indicated concentration or DMSO vehicle for the indicated times. Media was collected, concentrated, and analyzed for IL-6 by Western blotting. (B) PC3 were treated with silibinin at the indicated concentrations or DMSO vehicle for 72 hrs, and then incubated in low serum growth media for the indicated times. Media was collected, concentrated, and analyzed for IL-6 expression. (C–D) PC3 control conditioned media (CCM) and silibinin treated-PC3 conditioned media (SBCM) were collected as detailed in the Methods. Subsequently, PrSCs were exposed to PrSC basal media (basal), CCM or SBCM and analyzed for α-SMA (C) and vimentin (D) expression after 24 hrs. 50/50, 75/25, 100/0 denotes percentage conditioned media/basal PrSC growth media, respectively. β-actin was used as a loading control. Densitometric data are listed below each band as a fold change over their respective controls, N.D. denotes not detected. (E) PrSCs were exposed to basal media (basal) in the presence or absence of silibinin at the indicated concentrations for 24 hrs. At the end, total cell number (left panel) and dead cell percentage (right panel) were determined. Data shown in bar diagram represent mean ± SEM of four samples for each group. SB, silibinin.

Next, we analyzed the effect of silibinin treatment on the viability of PrSCs. PrSCs were exposed to silibinin (up to 100 µM) for 24 hrs, which resulted in statistically insignificant decreases in cell counts and cell death (Figure 2E). Therefore, in subsequent experiments in PrSCs, less than 100 µM silibinin doses were used.

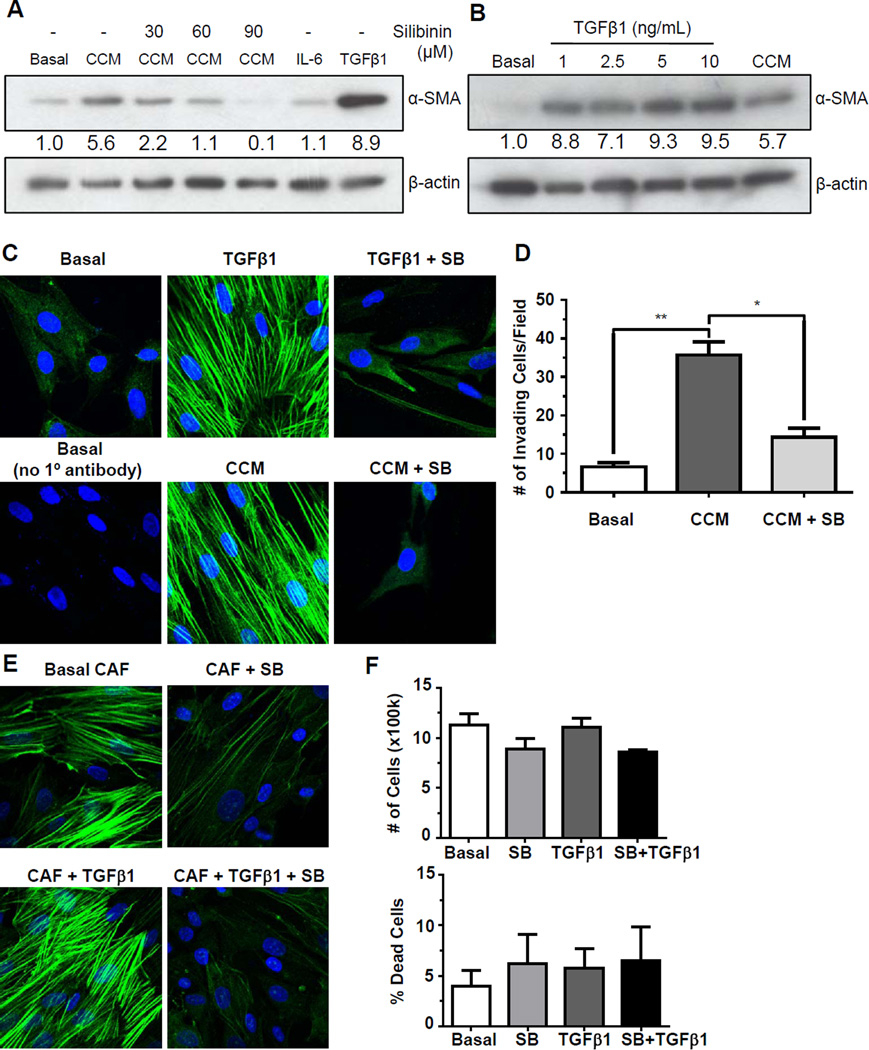

Figure 2.

Effect of silibinin on PC3 conditioned media induced transformation of PrSCs, and on constitutive and TGFβ1-induced α-SMA expression in CAFs. (A) PrSCs were exposed to basal media (basal), CCM ± silibinin (0, 30, 60, 90 µM), IL-6 (50 ng/mL), or TGFβ1 (10 ng/mL) and analyzed for α-SMA after 24 hrs. (B) PrSCs were exposed to basal media (basal), TGFβ1 at indicated concentrations, or CCM, and analyzed for α-SMA after 24 hrs. β-actin was used as a loading control. Densitometric data are listed below each band as a fold change over their respective controls. (C) PrSCs were exposed to basal media (basal), CCM ± silibinin (SB, 90 µM), or TGFβ1 (10 ng/mL) ± silibinin (90 µM) for 24 hrs, and probed for α-SMA (green) with α-SMA antibody and nuclei with DAPI (blue). (D) PrSCs were exposed to basal media (basal) or CCM ± silibinin (90 µM) and then seeded on Transwells after 24 hrs. PrSCs were allowed to invade through matrigel for 18 hrs and then invasive cells were counted. Data shown in bar diagram represent mean ± SEM of three samples for each group (**, p<0.01, *, p<0.05). (E) Prostate CAF cells were exposed to CAF basal media (basal) ± silibinin (90 µM) or TGFβ1 (10 ng/mL) ± silibinin (90 µM) for 24 hrs and probed for α-SMA (green) with α-SMA antibody and nuclei with DAPI (blue). (F) Prostate CAF cells were incubated in CAF basal media (basal) ± silibinin (90 µM) or treated with TGFβ1 (10 ng/mL) ± silibinin (90 µM) for 24 hrs. At the end, total cell number and dead cell percentage was determined. Data shown in bar diagram represent mean ± SEM of three samples for each group.

Silibinin directly inhibits CCM-mediated activation of PrSCs

Following the above described findings, we next sought to identify if silibinin could directly inhibit PrSC activation by CCM, and found that indeed silibinin (30–90 µM) dose-dependently inhibits CCM-induced α-SMA expression in PrSCs (Figure 2A). Interestingly, we also found that even high levels of recombinant IL-6 could not replicate the degree of α-SMA induction which was found in CCM-treated PrSCs, but TGFβ1 could (Figure 2A). This is consistent with the capacity of TGFβ1 to induce differentiation and α-SMA expression in fibroblasts [36]. Thus, we next attempted to replicate α-SMA expression induced by CCM with increasing concentrations of TGFβ1. This was found to roughly correspond to slightly less than 2.5 ng/mL TGFβ1 (Figure 2B).

While Western blot analysis identified CCM-mediated upregulation of α-SMA expression in PrSCs, immunofluorescent analysis confirmed an increase in the organization of α-SMA in both CCM- as well as TGFβ1-treated PrSCs (Figure 2C). Consistent with Western analysis, silibinin abrogated both CCM- and TGFβ1-mediated activation of α-SMA to baseline levels (Figure 2C). A sample with no primary antibody was used as a control for potential autofluorescence (Figure 2C). To determine if the reduction in α-SMA translated to a reduction in cell motility of PrSCs, an invasion assay was performed. PrSCs were incubated for 24 hrs in either low serum growth media or CCM in the presence or absence of silibinin. Following incubation, cells were seeded onto invasion chambers and allowed to migrate. As shown in Figure 2D, the presence of CCM induced migration of PrSCs which was significantly decreased by silibinin.

We next examined the direct effect of silibinin on human prostate fibroblasts isolated from clinical resections of PCA, and thus, are an excellent model to assay interventions on activated, cancer-associated fibroblasts. These prostate CAFs exhibited strong baseline expression and organization of α-SMA that was further enhanced by TGFβ1, and both constitutive and TGFβ1-induced α-SMA expression was abrogated by silibinin (Figure 2E). To confirm that this silibinin-mediated α-SMA inhibition was not a consequence of cellular death, we performed a cell viability assay where silibinin (90 µM) treatment resulted in only a slightly lower cell count and higher cell death, though these were not found to be statistically significant (Figure 2F).

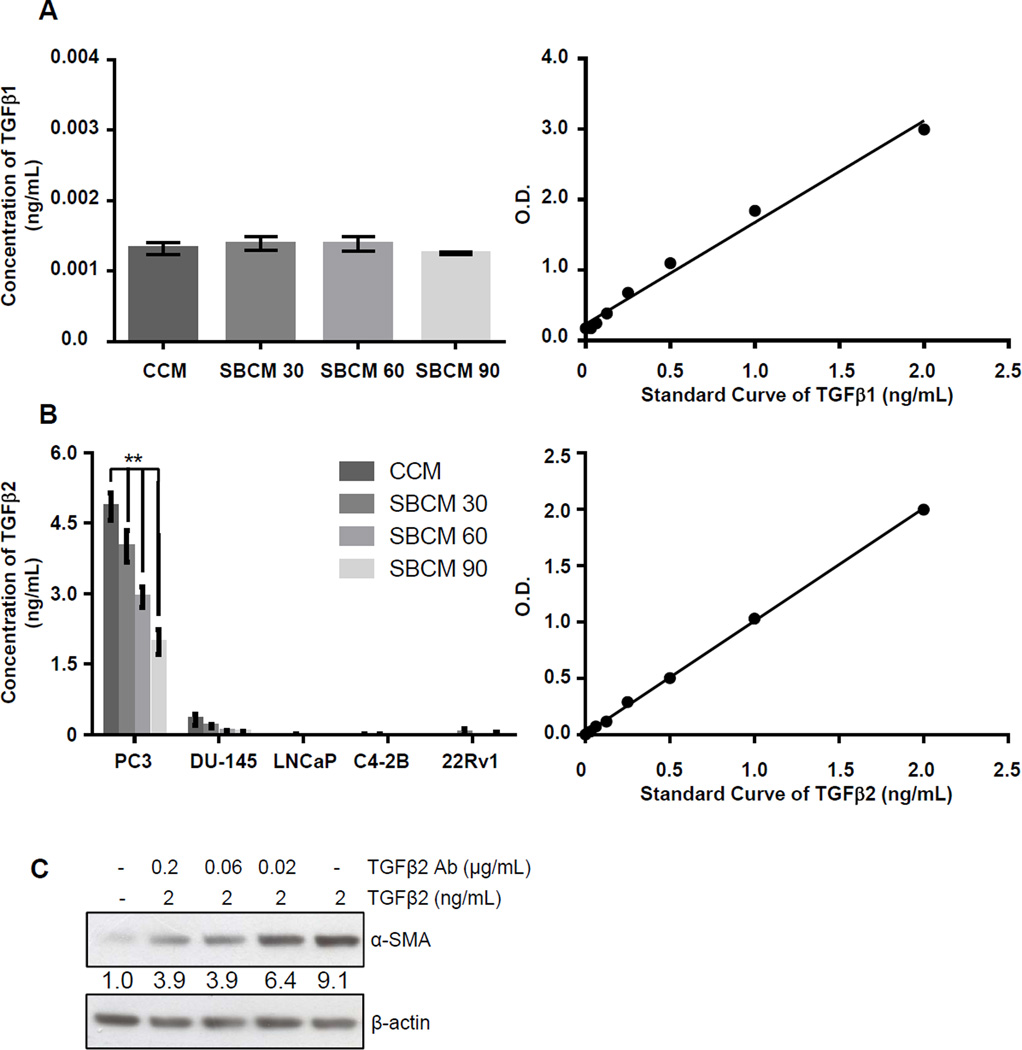

TGFβ2 is a major component of CCM

To more precisely determine the concentration of TGFβ1 in CCM as well as to determine if the inhibition seen in ±-SMA and vimentin expression by SBCM was a consequence of a direct reduction in TGFβ1 secretion by PCA cells following silibinin treatment, we assayed conditioned media with a TGFβ1 ELISA. Surprisingly, we found that in CCM as well as in SBCM 30, 60 and 90, the expression of TGFβ1 was very low (roughly 1 pg/mL), in fact near the detection limit of the assay (Figure 3A). Based on the robust activation of PrSCs elicited by CCM despite the minimal levels of detected TGFβ1, we next assayed for another TGFβ isoform i.e. TGFβ2 in CCM. Here we detected more than 4 ng/mL of TGFβ2 in CCM which was dose-dependently decreased by silibinin (Figure 3B). Another PCA cell line, DU-145, also secreted substantial amounts of TGFβ2, though to a lower degree as compared to PC3 cells, which was also dose-dependently decreased by silibinin (Figure 3B). In other PCA cell lines LNCaP, C4-2B and 22Rv1, TGFβ2 expression measured by ELISA was either undetectable or extremely low (Figure 3B). As a control for further studies, we also confirmed that the TGFβ2-mediated increase in the expression of α-SMA in PrSCs could be inhibited by TGFβ2 specific antibody (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

TGFβ isotypes expression in PCA cells, and TGFβ2 role in inducing α-SMA in prostate fibroblasts. (A) TGFβ1 expression was analyzed by ELISA in CCM and SBCM 30, 60, and 90 from human PCA PC3 cells as detailed in Methods. Regression curve used to quantify results is also shown. Data shown in the bar diagram represent mean ± SEM of three samples for each group. (B) TGFβ2 expression was analyzed by ELISA in CCM and SBCM 30, 60, and 90 from the listed human PCA cell lines. Regression curve used to quantify results is also shown. Data shown in bar diagram represent mean ± SEM of three samples for each group, (**, p<0.001) (C) PrSCs were incubated in the presence or the absence of TGFβ2 and TGFβ2 neutralizing antibody at indicated concentrations for 24 hrs. Thereafter, PrSCs were collected and analyzed for α-SMA expression by Western blotting. β-actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry data are listed below each band as a fold change over their respective controls.

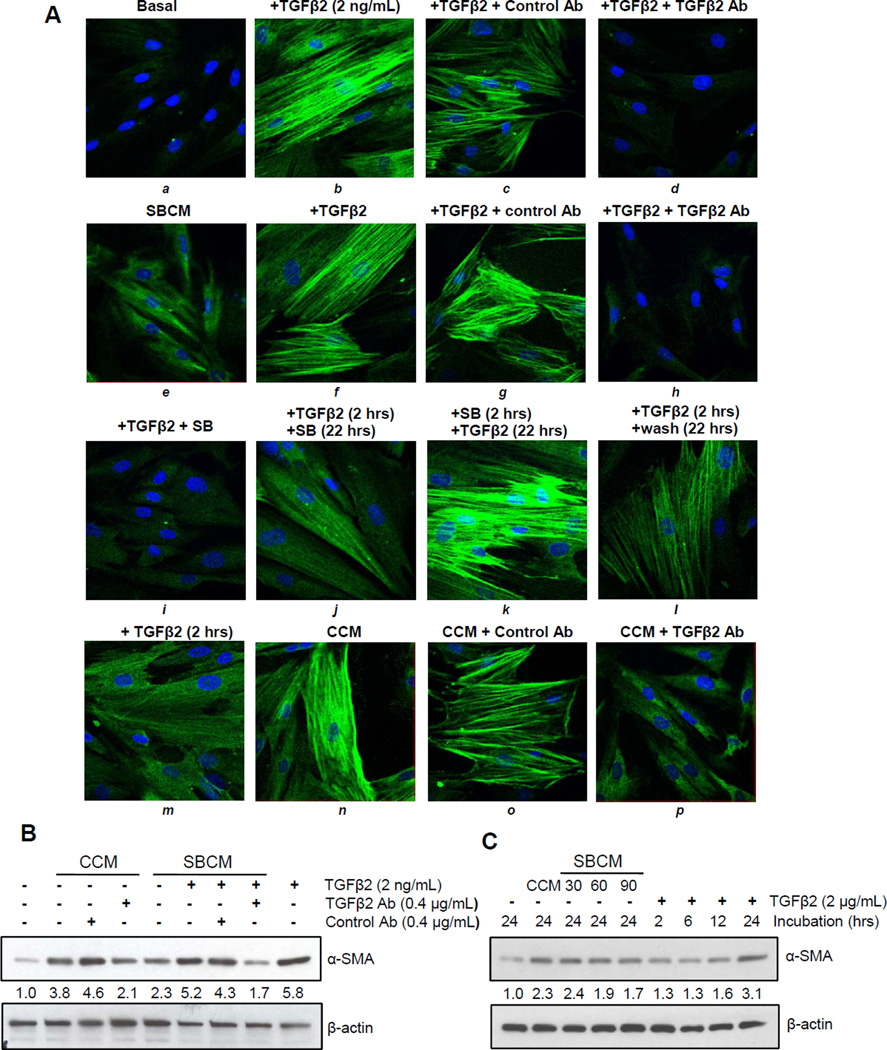

Both silibinin and TGFβ2 neutralizing antibody inhibit TGFβ2- as well as CCM-mediated expression of α-SMA in PrSCs

We next sought to confirm the role of TGFβ2 in CCM-mediated activation of PrSCs. We found that neutralizing antibody to TGFβ2 could abrogate TGFβ2-mediated upregulation of α-SMA as detected by immunofluorescence (Figure 4A, a–d). This effect was also found in the relatively modest activation by SBCM, as well as the more robust α-SMA activation induced in SBCM fortified with exogenous TGFβ2, which was also abrogated by TGFβ2 neutralizing antibody (Figure 4A, e–h). Importantly, we found that simultaneous silibinin treatment with TGFβ2 abrogates α-SMA activation, but could only modestly do so if applied 2 hrs after TGFβ2 treatment; however, silibinin failed to inhibit α-SMA activation if it is removed 2 hrs after its treatment followed by TGFβ2 stimulation for 22 hrs (Figure 4A, i–k). A stimulation of PrSCs with TGFβ2 for 2 hrs followed by wash out for 22 hrs or only 2 hrs TGFβ2 stimulation of PrSCs produced only marginal activation of α-SMA which was comparable to that observed with SBCM (Figure 4A, j–m). Next, we also confirmed the inhibitory effect of TGFβ2 neutralizing antibody on CCM-induced activation of α-SMA in PrSCs by immunofluorescence (Figure 4A, n–p) and western blotting (Figure 4B), where neutralizing antibody inhibited α-SMA expression induced by CCM as well as that by SBCM fortified with TGFβ2 (Figure 4B). In light of our results showing a temporal sensitivity to silibinin-mediated inhibition of α-SMA activation in PrSCs (Figures 4A), we also examined the time course of TGFβ2–mediated increase of α-SMA expression. As expected, α-SMA expression increased in PrSCs with treatment time, and we further confirmed that increasing concentration of silibinin treatment reduced the capacity of PC3 to potently condition media to activate PrSCs (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Contribution of TGFβ2 to PC3 conditioned media-caused induction of α-SMA in PrSCs. (A) PrSCs were exposed to basal media (basal), CCM, or SBCM, in presence or absence of silibinin and/or TGFβ2 at indicated concentrations. In specific cases, 2 hrs treated PrSCs were analyzed or washed and then incubated with basal media or media supplemented with silibinin or TGFβ2 for an additional 22 hrs. After a total of 24 hrs, cells were analyzed for α-SMA either by (A) immunofluorescence or (B–C) Western blot analysis. β-actin was used as a loading control. Densitometric data are listed below each band as a fold change over their respective controls.

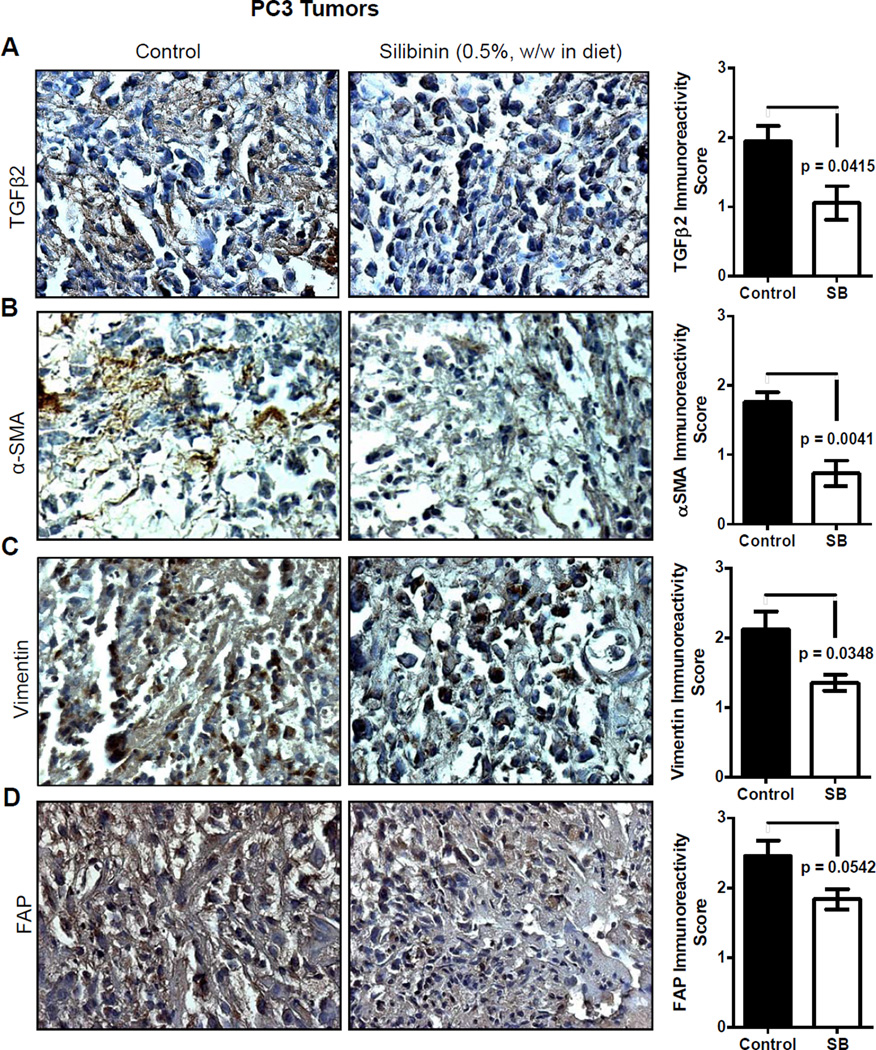

Silibinin inhibits TGFβ2 expression in vivo, corresponding to a reduction in activated fibroblast biomarkers

While promising, our studies to this point were conducted in cell culture, and it remained to be determined if silibinin' effects could be replicated in a milieu closer to a clinical setting. To this end, PC3 tumor tissues from a recently completed study by us were employed to address this next avenue of investigation; notably, we have reported that silibinin feeding (0.5%, w/w in diet) strongly inhibits the growth of PC3 tumors in nude mice [34]. Consistent with our model highlighting the relevance of otherwise normal tissues that happen to interface with an incipient lesion, we report that immunohistochemical staining for TGFβ2 and CAF-like biomarkers (α-SMA, vimentin, and FAP) exhibited strong localization to the periphery of tumor sections. Also importantly, PC3 tumor tissues from silibinin-fed mice exhibited significantly reduced TGFβ2 expression (Figure 5A) and this phenomenon also corroborated with a decrease in α-SMA, vimentin and FAP expression (Figure 5B–D).

Figure 5.

Effect of silibinin feeding on the expression of TGFβ2 and CAF-like biomarkers in PC3 tumors. PC3 tumor tissues were analyzed by IHC to determine silibinin’s effects on the expression of (A) TGFβ2, (B) α-SMA, (C) vimentin, and (D) FAP. Immunoreactivity (represented by brown staining) of these biomarkers was scored as 0+ (no staining), 1+ (weak staining), 2+ (moderate staining), 3+ (strong staining), and 4+ (very strong staining). Data shown in bar diagram represent mean ± SEM of three to five samples for each group. SB, silibinin.

DISCUSSION

Studies focused on elucidating the cellular dysfunction and disrupted signaling pathways involved in carcinogenesis have done much to identify and characterize novel avenues for the detection, management, and treatment of various cancers. These efforts have also enumerated a host of agents both exogenous and endogenous that lend momentum to the progression of these diseases. They have to date generally focused on the gain or loss of gene function within cancer cells that provide the tumor as a whole the means to escape growth regulation and host immunity [1–5,7–9]. The potential for contribution by tissues adjacent to the developing tumor has only recently emerged, but has gained a great deal of interest. In regards to this latter aspect, the series of reciprocal interactions in a developing cancerous lesion and the stroma surrounding it have become recognized as a major component for malignancy. This becomes more obviously relevant with the interpretation of a tumor as a chronically persistent wound. This injury then drives inflammation, which has been well-documented as associated with cancers in general and PCA particularly [37–39]. This inflammation in turn drives a runaway wound healing program, chronically recruiting and activating nearby fibroblasts, altering them into a myofibroblastic or CAF-like phenotype competent to remodel the ECM and allow for cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis, as well as angiogenesis [10–14]. This is as a consequence of the physiological properties of myofibroblasts and their primary role in wound healing. Through extensive expression and organization of α-SMA, they exhibit potent contractile properties allowing for the gross manipulation of ECM microstructure to close a wound, or in the case of a tumor, to inadvertently disrupt the ECM to facilitate cancer cell EMT [40,41]. This phenomenon was confirmed in our study where exposure to PCA conditioned media amplified both the expression and organization of α-SMA in what were initially human prostate fibroblasts. This translated to a marked induction of invasiveness in PrSCs as a consequence of exposure to CCM.

As a result of this chronic inflammation and the interplay of several different cell types, a host of signaling molecules have been presented as potential contributors to this effect. We first assayed for the effect of IL-6, a well-established inflammatory mediator [20], and then of TGFβ1, reported to contribute to carcinogenesis in several tumor models, including PCA [36,42–44]. However, we conducted the majority of our work focusing on TGFβ2, on the basis of its capacity to induce α-SMA as well as analysis of conditioned media by ELISA. The specific role of TGFβ2 in mediating the effects of conditioned media on PrSCs was confirmed by specific neutralizing antibody. As mentioned, TGFβ family expression is found to be elevated in many hyperplastic disorders, among them carcinomas [21]. Yet, in normal epithelial tissues, it is associated with promoting apoptosis and inhibiting proliferation. This property reverses as cancer advances, TGFβ appearing to lose the capacity to maintain homeostasis and instead promoting proliferation and EMT [21–23]. This may be a consequence of interplay between TGFβ and other signaling factors within the stroma. Here we show that the addition of TGFβ (1 or 2) elicited a similar effect as that elicited by CCM, both serving to increase the expression and organization of α–SMA in PrSCs. Interestingly, PCA cells in culture expressed significantly higher amounts of TGFβ2 compared to TGFβ1, which was strongly decreased by silibinin treatment. In future studies, we will further analyze the mechanism through which silibinin targets TGFβ expression in PCA cells.

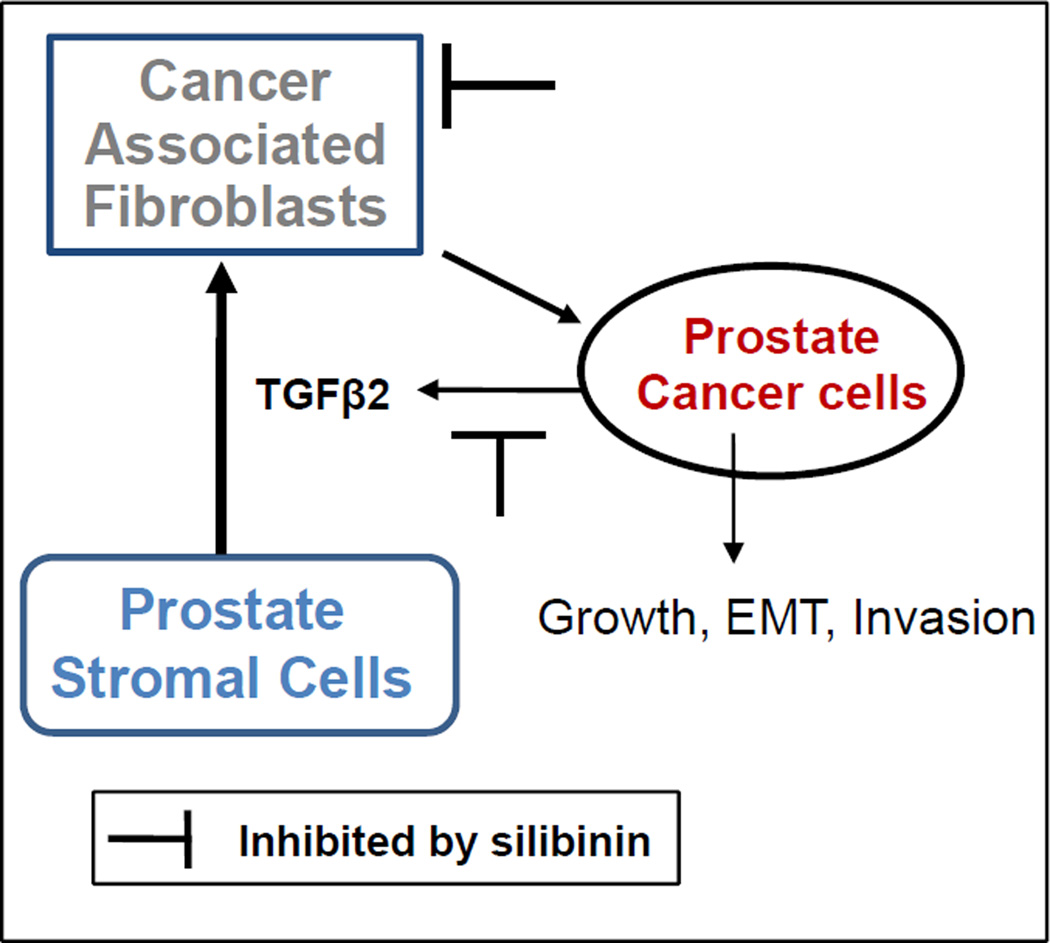

Overall, we report here that silibinin inhibits the capacity of PCA cells to induce a CAF-like phenotype in PrSCs both by direct intervention of PrSCs but also indirectly by acting on PCA cells' capacity to secrete TGFβ2 as summarized in Figure 6. This direct intervention was found in cases where TGFβ2 was exogenously added as a positive control, consistent with a report where silibinin treatment inhibited trans-differentiation of human tenon fibroblasts by TGFβ1 [45], as well as in CAF cells that constitutively expressed markers for activated fibroblasts (summarized in Figure 6). This is further in line with extensive data supporting silibinin's potent inhibition of an array of PCA properties: altering deregulated cell signaling [25–27], inhibiting proliferation [26,28,29], EMT [30–32], and angiogenesis [29]. Our findings lend support to the notion that in addition to these well-established features, silibinin might also target the newly characterized interaction between PCA cells and their surrounding microenvironment, critical for the development and progression of a malignant tumor and as such opens the possibility for use of this agent as more than a potential therapeutic but also a prophylaxis, preventing an incipient lesion from gaining the foothold required to expand beyond its current microenvironment. In this regard, it is important to highlight that silibinin has entered phase I/II clinical trial in PCA patients, and completed dose-escalation studies show that the concentrations of silibinin employed in our present cell culture studies are those which are physiologically achievable in the serum of PCA patients [46], which further signifies the translational potential of our findings in the present study to prevent and manage PCA clinically.

Figure 6.

Schematic for the induction of a CAF-like phenotype by PCA cells and potential target for intervention by silibinin. Silibinin treatment inhibited PCA cells induced transformation of prostate stromal cells into a CAF-like phenotype via targeting TGFβ2 expression. Silibinin treatment also directly decreased α-SMA expression in CAF cells.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported by NCI RO1 grant CA102514.

List of Abbreviations

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- α-SMA

Alpha-smooth muscle actin

- CAF

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

- CCM

Control conditioned media

- DAB

3,3’-diaminobenzidine

- DAPI

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FAP

Fibroblast activation protein

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IL6

Interleukin 6

- PCA

Prostate cancer

- PrSCs

Prostate stromal cells

- SBCM

Silibinin conditioned media

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- STR

Short tandem repeat

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- TM

Tumor microenvironment

REFERENCES

- 1.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:3030–3044. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belpomme D, Irigaray P, Hardell L, et al. The multitude and diversity of environmental carcinogens. Environ Res. 2007;105:414–429. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer--analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:78–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loeb KR, Loeb LA. Significance of multiple mutations in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:379–385. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mucci LA, Wedren S, Tamimi RM, Trichopoulos D, Adami HO. The role of gene-environment interaction in the aetiology of human cancer: examples from cancers of the large bowel, lung and breast. J Intern Med. 2001;249:477–493. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irigaray P, Newby JA, Clapp R, et al. Lifestyle-related factors and environmental agents causing cancer: an overview. Biomed Pharmacother. 2007;61:640–658. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willett WC. Diet and cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5:393–404. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez C, McCullough ML, Mondul AM, et al. Meat consumption among Black and White men and risk of prostate cancer in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:211–216. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, Fan X, Houghton J. Tumor microenvironment: the role of the tumor stroma in cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:805–815. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tlsty TD, Coussens LM. Tumor stroma and regulation of cancer development. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:119–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhowmick NA, Moses HL. Tumor-stroma interactions. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barclay WW, Woodruff RD, Hall MC, Cramer SD. A system for studying epithelial-stromal interactions reveals distinct inductive abilities of stromal cells from benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Endocrinology. 2005;146:13–18. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olumi AF, Grossfeld GD, Hayward SW, Carroll PR, Tlsty TD, Cunha GR. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deep G, Agarwal R. Targeting Tumor Micro environment with Silibinin: Promise and Potential for a Translational Cancer Chemopreventive Strategy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2013 doi: 10.2174/15680096113139990041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen RC, Clark JA, Talcott JA. Individualizing quality-of-life outcomes reporting: how localized prostate cancer treatments affect patients with different levels of baseline urinary, bowel, and sexual function. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3916–3922. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanford JL, Feng Z, Hamilton AS, et al. Urinary and sexual function after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. JAMA. 2000;283:354–360. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giannoni E, Bianchini F, Masieri L, et al. Reciprocal activation of prostate cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts stimulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stemness. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6945–6956. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santibanez JF, Quintanilla M, Bernabeu C. TGF-beta/TGF-beta receptor system and its role in physiological and pathological conditions. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011;121:233–251. doi: 10.1042/CS20110086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikushima H, Miyazono K. TGF-beta signal transduction spreading to a wider field: a broad variety of mechanisms for context-dependent effects of TGF-beta. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:37–49. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bierie B, Moses HL. Tumour microenvironment: TGFbeta: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:506–520. doi: 10.1038/nrc1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pradhan SC, Girish C. Hepatoprotective herbal drug, silymarin from experimental pharmacology to clinical medicine. Indian J Med Res. 2006;124:491–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhanalakshmi S, Singh RP, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits constitutive and TNF alpha-induced activation of NF-kappaB and sensitizes human prostate carcinoma DU145 cells to TNF alpha-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:1759–1767. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agarwal C, Tyagi A, Kaur M, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits constitutive activation of Stat3, and causes caspase activation and apoptotic death of human prostate carcinoma DU145 cells. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1463–1470. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyagi A, Sharma Y, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Silibinin impairs constitutively active TGF alpha-EGFR autocrine loop in advanced human prostate carcinoma cells. Pharm Res. 2008;25:2143–2150. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9545-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyagi A, Bhatia N, Condon MS, Bosland MC, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of silibinin in rat prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2002;53:211–217. doi: 10.1002/pros.10146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh RP, Sharma G, Dhanalakshmi S, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Suppression of advanced human prostate tumor growth in athymic mice by silibinin feeding is associated with reduced cell proliferation, increased apoptosis, and inhibition of angiogenesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:933–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deep G, Gangar SC, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Role of E-cadherin in antimigratory and anti invasive efficacy of silibinin in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1222–1232. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu K, Zeng J, Li L, et al. Silibinin reverses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in metastatic prostate cancer cells by targeting transcription factors. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:1545–1552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raina K, Rajamanickam S, Singh RP, Deep G, Chittezhath M, Agarwal R. Stage-specific inhibitory effects and associated mechanisms of silibinin on tumor progression and metastasis in transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate model. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6822–6830. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zi X, Feyes DK, Agarwal R. Anticarcinogenic effect of a flavonoid antioxidant, silymarin, in human breast cancer cells MDA-MB 468: induction of G1 arrest through an increase in Cip1/p21 concomitant with a decrease in kinase activity of cyclin-dependent kinases and associated cyclins. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1055–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh RP, Deep G, Blouin MJ, Pollak MN, Agarwal R. Silibinin suppresses in vivo growth of human prostate carcinoma PC-3 tumor xenograft. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2567–2574. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deep G, Raina K, Singh RP, Oberlies NH, Kroll DJ, Agarwal R. Isosilibinin inhibits advanced human prostate cancer growth in athymic nude mice: comparison with silymarin and silibinin. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2750–2758. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bremnes RM, Donnem T, Al-Saad S, et al. The role of tumor stroma in cancer progression and prognosis: emphasis on carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:209–217. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f8a1bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Marzo AM, Platz EA, Sutcliffe S, et al. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:256–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sfanos KS, De Marzo AM. Prostate cancer and inflammation: the evidence. Histopathology. 2012;60:199–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hinz B, Mastrangelo D, Iselin CE, Chaponnier C, Gabbiani G. Mechanical tension controls granulation tissue contractile activity and myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1009–1020. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61776-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grinnell F. Fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and wound contraction. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:401–404. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andreassen CN, Alsner J, Overgaard J, et al. TGFB1 polymorphisms are associated with risk of late normal tissue complications in the breast after radiotherapy for early breast cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2005;75:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ewart-Toland A, Chan JM, Yuan J, Balmain A, Ma J. A gain of function TGFB1 polymorphism may be associated with late stage prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:759–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soulitzis N, Karyotis I, Delakas D, Spandidos DA. Expression analysis of peptide growth factors VEGF, FGF2, TGFB1, EGF and IGF1 in prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:305–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen YH, Liang CM, Chen CL, et al. Silibinin inhibits myofibroblast transdifferentiation in human tenon fibroblasts and reduces fibrosis in a rabbit trabeculectomy model. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/aos.12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flaig TW, Gustafson DL, Su LJ, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of silybin-phytosome in prostate cancer patients. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25:139–146. doi: 10.1007/s10637-006-9019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]