Abstract

Introduction

The efficacy and safety of the once-daily topical ophthalmic solutions, alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2%, in preventing ocular itching associated with allergic conjunctivitis were evaluated.

Methods

Pooled analysis was conducted of two double-masked, multicenter, active- and placebo-controlled studies using the conjunctival allergen challenge (CAC) model of allergic conjunctivitis. Subjects were randomized 1:1:1 to receive alcaftadine 0.25%, olopatadine 0.2%, or placebo. The primary efficacy measure was subject-evaluated mean ocular itching at 3 min post-CAC and 16 h after treatment instillation. Secondary measures included ocular itching at 5 and 7 min post-CAC. Ocular itch was determined over all time points measured (3, 5, and 7 min) post-CAC and the proportion of subjects with minimal itch (itch score <1) and zero itch (itch score = 0) was also assessed.

Results

A total of 284 subjects were enrolled in the two studies. At 3 min post-CAC and 16 h after treatment instillation, alcaftadine 0.25% achieved a significantly lower mean itch score compared with olopatadine 0.2% (0.50 vs. 0.87, respectively; P = 0.0006). Alcaftadine demonstrated a significantly lower mean itch score over all time points compared with olopatadine (0.68 vs. 0.92, respectively; P = 0.0390); both alcaftadine- and olopatadine-treated subjects achieved significantly lower overall mean ocular itching scores compared with placebo (2.10; P < 0.0001 for both actives). Minimal itch over all time points was reported by 76.1% of alcaftadine-treated subjects compared with 58.1% of olopatadine-treated subjects (P = 0.0121). Treatment with alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% was safe and well tolerated; no serious adverse events were reported.

Conclusion

Once-daily alcaftadine 0.25% ophthalmic solution demonstrated greater efficacy in prevention of ocular itching compared with olopatadine 0.2% at 3 min post-CAC (primary endpoint), and over all time points, 16 h post-treatment instillation. Alcaftadine and olopatadine both provided effective relief compared with placebo and were generally well tolerated.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-014-0155-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Alcaftadine, Allergic conjunctivitis, Antiallergic, Conjunctival allergen challenge model, Ocular itch, Olopatadine, Ophthalmology

Introduction

Allergic conjunctivitis is one of the most common conditions requiring treatment by ophthalmologists, optometrists, and allergists [1]. While prevalence studies of conjunctivitis alone are limited, epidemiologic data have been derived from studies of the commonly coexisting nasal symptoms or rhinoconjunctivitis and are wide ranging with large global variations [2, 3]. In the United States, the Allergies in America survey conducted in 2006 estimated that 14.2% of the adult population had been affected by allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, while a more recent analysis based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III data in a sample size of 20,010 adults found that 40% of participants were affected by allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in a 12-month period [2, 4, 5]. The International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood spanning 52 countries reported that allergic conjunctivitis affects 1.4–39.7% of children and adolescents [6].

Ocular itching, the hallmark symptom of allergic conjunctivitis, is often accompanied by tearing, conjunctival redness, eyelid swelling, and chemosis [7]. Allergic conjunctivitis is mediated by immunoglobulin E-activated degranulation of mast cells and the release of a cascade of inflammatory mediators, including histamine, in response to allergens [8, 9]. Histamine release and activation of histamine H1 receptors in the conjunctiva leads to ocular itching, while stimulation of H2 receptors on the ocular surface results in vasodilation and is associated with ocular redness, eyelid swelling, and chemosis [10, 11]. Recent evidence suggests that histamine binding to and activation of H4 receptors also play a role in allergic conjunctivitis [12, 13]. Topical ophthalmic antihistamines are the primary treatment options for allergic conjunctivitis. Currently, alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% are the only approved once-daily ophthalmic solutions for allergic conjunctivitis in the United States [14–19]. Both olopatadine and alcaftadine are classified as dual-action antiallergic agents, directly inhibiting histamine receptor activation and indirectly reducing allergic responses by stabilizing mast cells [20].

Clinical studies evaluating alcaftadine and olopatadine as treatment options for allergic conjunctivitis have used the conjunctival allergen challenge (CAC) model to assess clinical efficacy [21, 22]. The CAC model was designed to mimic the signs and symptoms of an ocular allergic response in a controlled setting, providing an alternative to environmental allergy trials that are subject to variable allergen exposures. The model has been established as the standard for demonstrating efficacy and safety of topical ophthalmic antiallergic solutions seeking approval from the United States Food and Drug Administration [21]. CAC testing consists of instillation of the study drug or comparator(s) into the eye followed by an allergen challenge at a predetermined time post-instillation. The effect is then graded using a standardized severity scale, allowing assessment of both the onset of action and duration of effect [15, 17, 22–26].

Two recently completed similarly designed studies are the first to have compared the efficacy and duration of action of once-daily alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% and placebo using the CAC model. The first study demonstrated that alcaftadine 0.25% was safe and effective in preventing signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis at both 16 and 24 h after treatment instillation [26]. Differences in treatment effect between alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% were most pronounced at the earliest time point post-CAC, when alcaftadine 0.25% ophthalmic solution was statistically superior to olopatadine 0.2% ophthalmic solution. The second study further assessed treatment outcome and confirmed statistical superiority of treatment with alcaftadine 0.25% relative to olopatadine 0.2% in mean itch reduction at the same time point post-CAC, at 16 h after treatment instillation [27, 28]. A pooled analysis of the data collected from the two studies was completed to further characterize treatment differences between alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% ophthalmic solutions.

Methods

Study Design

Two multicenter, double-masked, randomized active- and placebo-controlled trials (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01470118 and #NCT01732757) were conducted between October 2011 and December 2012. Protocols and informed consent forms were approved by an independent review board (Alpha IRB, San Clemente, CA, USA). Studies were conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008, and International Conference of Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. Subjects provided written informed consent (or assent with a consent form signed by the subject’s legally authorized representative) and signed authorization for the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act before any study-related procedures or changes in treatment.

Study Eligibility Criteria

Subject eligibility was identical for both studies. Key inclusion criteria included subjects with a history of ocular allergies and at least one positive skin test within 24 months of the trial start date to one of the following: cat dander, grasses, ragweed, dog dander, cockroach, dust mites, and trees; a best-corrected visual acuity ≥0.6 on the logMAR scale (using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study chart). Subjects must have had a positive bilateral CAC reaction (defined as ≥2 itching and ≥2 redness in the conjunctival vessel bed) within 10 min of instillation of the last titration of allergen at visit 1 and in at least two of three time points at visit 2. All subjects agreed to avoid disallowed medications and to discontinue contact lens wear for the designated period.

Key exclusion criteria included subjects with any baseline itching or a redness score >1 in any vessel bed at each visit; any known allergy, contraindications, or sensitivity to the study medications; systemic or ocular condition in the opinion of the investigator that could affect safety or trial parameters; ocular surgery within 3 months or refractive surgery within 6 months; signs of active allergic conjunctivitis at the start of any visit; presence of an active ocular infection (bacterial, viral, or fungal); or history of herpetic ocular disease. Owing to the potential for randomization into a treatment arm with a pregnancy category C therapeutic [19], women who were pregnant or planning a pregnancy, lactating, or of child-bearing age and not using a medically acceptable form of birth control for the entire period of the trials were excluded. Subjects planning surgical procedures during the trial period or those with a history of retinal detachment, diabetic retinopathy, or progressive retinal disease also were ineligible.

Treatment and Assessments

Assessments from the three identical subject visits of both studies were included in the pooled analysis. At the first study visit (day −21 ± 3) or titration visit, allergens were instilled in each eye followed by the subject rating ocular itching severity at 10 min. Allergen concentrations were increased serially until the scores for both itching and conjunctival redness reached ≥2.0. The maximal allergen concentration used during this titration visit was utilized for all subsequent visits. Itching severity was graded using a five-point scale (0–4), which allowed for half measures [15, 17, 21, 23–26]. Conjunctival redness was scored by the investigator using a five-point ocular redness scale (0–4) [15, 17, 21, 23–26].

At the second study visit (day −14 ± 3) or confirmation visit, allergen challenge using the final concentration from the first visit was performed to provide baseline data for those subjects who continued to satisfy eligibility criteria. Subjects rated ocular itching at 3, 5, and 7 min after allergen instillation. Subjects who met the qualifying criteria of post-challenge bilateral itching ≥2 and who also had bilateral conjunctival redness ≥2 at two of the three time points (7, 15, and 20 min) continued to visit 3A approximately 2 weeks after visit 2.

At visit 3A (day 0), subjects were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive one drop of masked ophthalmic solution in both eyes: alcaftadine 0.25% ophthalmic solution (Lastacaft®, Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA), olopatadine 0.2% ophthalmic solution (Pataday®, Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA), and placebo: 0.3% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (Tears Naturale® II, Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA). Subjects returned approximately 15.5 h after treatment instillation (visit 3B) and were challenged 16 + 1 h after study drug instillation in both eyes using the same allergen and dose that had elicited a positive reaction at visits 1 and 2. The first study also had a fourth visit that was used to assess duration of action at 24 h post-treatment instillation.

Efficacy and Safety Parameters

The primary efficacy endpoint was ocular itching quantified by the subject at 3 min post-CAC. Secondary efficacy endpoints included ocular itching evaluated by the subject at 5 and 7 min post-CAC. Safety was assessed by monitoring adverse events (elicited and observed) throughout the studies, which were then coded to system organ class and preferred terms using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 13.1 [29].

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

Both eyes of each subject were used for statistical summaries and analyses. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics, including the number of observations, mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum values. Hypothesis testing, unless otherwise indicated, was performed at the 5% significance level of type I error for two-sided tests. The last observation carried forward method was used to handle missing and incomplete efficacy data for the primary measure. All secondary efficacy measures were analyzed using observed data only.

The intent-to-treat population, comprised of all subjects who were randomized, was used for the efficacy analyses. A subset of the intent-to-treat population, consisting of subjects who completed the study with no protocol violations, formed the per-protocol population. This population was analyzed as treated using observed data only and was used for confirmatory analyses. The safety population included all randomized subjects who received at least one dose of the study treatment.

The primary efficacy measure was summarized by visit, time point, and treatment group using descriptive statistics. The differences in the means between treatment groups were calculated, and mean ocular itching scores for each of the treatments were compared using two-sample t tests. In addition, the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test at each time point and repeated measures analysis of covariance model accounting for treatment and repeated time measurements within each visit were performed. Predefined analyses on the primary efficacy data, ocular itch, both at each time point and over all time points, included comparisons of the number of subjects in each group with minimal itch (defined as itch score <1), and the number of subjects with zero itch (defined as itch score = 0). Fisher’s exact test was conducted for comparisons at each time point and over all time points for each pair of treatments (alcaftadine versus placebo, olopatadine versus placebo, and alcaftadine versus olopatadine). Secondary ocular itch efficacy measures were summarized using descriptive statistics by visit, time point, and treatment group, and statistically analyzed in the same way as the primary measure. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Subject Demographics and Characteristics

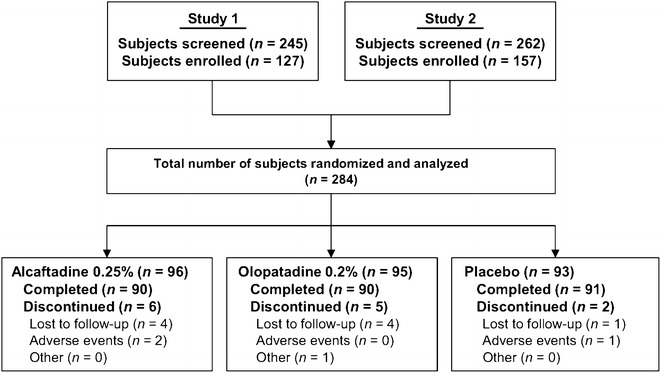

A total of 284 subjects were enrolled in the two clinical studies following screening visits 1 and 2; 96 subjects were randomized to receive alcaftadine 0.25% ophthalmic solution, 95 received olopatadine 0.2% ophthalmic solution, and 93 received placebo. Thirteen of the 284 randomized subjects (alcaftadine 0.25%, n = 6; olopatadine 0.2%, n = 5; placebo, n = 2) did not complete the studies. The most common reasons for treatment discontinuation across treatment arms were loss to follow-up and adverse events (Fig. 1). Subject demographics were well balanced among the three treatment groups with no significant differences with regard to age, gender, or race, while iris color differed significantly among groups (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Subject disposition

Table 1.

Pooled analysis demographics (intent-to-treat population)

| Characteristica | Alcaftadine 0.25% (n = 96) | Olopatadine 0.2% (n = 95) | Placebo (n = 93) | All subjects (n = 284) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.601* | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 38.7 ± 13.1 | 37.9 ± 14.9 | 36.7 ± 12.6 | 37.8 ± 13.6 | |

| Min–max | 12–70 | 12–74 | 14–68 | 12–74 | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.488† | ||||

| Male | 33 (34.4) | 33 (34.7) | 39 (41.9) | 105 (37.0) | |

| Female | 63 (65.6) | 62 (65.3) | 54 (58.1) | 179 (63.0) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 1.000† | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (9.4) | 9 (9.5) | 9 (9.7) | 27 (9.5) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 87 (90.6) | 86 (90.5) | 84 (90.3) | 257 (90.5) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.912† | ||||

| African American | 12 (12.5) | 15 (15.8) | 16 (17.2) | 43 (15.1) | |

| Asian | 19 (19.8) | 20 (21.1) | 20 (21.5) | 59 (20.8) | |

| Caucasian | 56 (58.3) | 53 (55.8) | 53 (57.0) | 162 (57.0) | |

| Other | 9 (9.4) | 7 (7.4) | 4 (4.3) | 20 (7.0) | |

| Iris color, n (%) | <0.0001† | ||||

| Brown | 118 (61.5) | 118 (62.1) | 124 (66.7) | 360 (63.4) | |

| Blue | 38 (19.8) | 40 (21.1) | 22 (11.8) | 100 (17.6) | |

| Green | 28 (14.6) | 6 (3.2) | 22 (11.8) | 56 (9.9) | |

| Hazel | 4 (2.1) | 20 (10.5) | 14 (7.5) | 38 (6.7) | |

| Black | 4 (2.1) | 6 (3.2) | 2 (1.1) | 12 (2.1) | |

| Gray | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.4) |

Max maximum, Min minimum, SD standard deviation

*Analysis of variance, † Fisher’s exact test

aPercentages are based on the total number of subjects in each treatment group except for iris color, which is based on the total number of eyes in each treatment group

Efficacy Outcome Measures

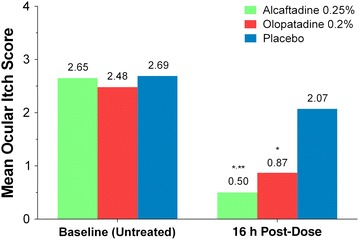

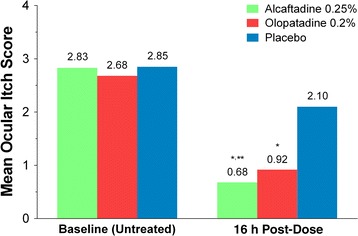

For the primary efficacy endpoint, ocular itching at 3 min post-CAC and 16 h after treatment instillation, alcaftadine 0.25% achieved a statistically significant lower mean itch score compared with olopatadine 0.2% (0.50 vs. 0.87, respectively; P = 0.0006; Fig. 2). Analysis over all the time points measured (3, 5, and 7 min) also demonstrated a statistically lower overall mean itch score with alcaftadine 0.25% compared with olopatadine 0.2% (0.68 vs. 0.92, respectively; P = 0.0390; Fig. 3). Both alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% were superior to placebo for achieving greater reductions in mean itch scores at 3, 5, and 7 min post-CAC and over all time points (P < 0.0001 for both alcaftadine and olopatadine versus placebo; Table 2). Alcaftadine 0.25%-treated subjects consistently demonstrated greater percentage reduction in itching from baseline at 3, 5, and 7 min post-CAC (−81.0%, −74.1%, and −70.6%, respectively) compared with olopatadine 0.2%-treated subjects (−63.2%, −65.7%, and −65.2%, respectively). For both actives, the percentage reduction in itching from baseline was superior over placebo at 3, 5, and 7 min (−23.7%, −24.1%, and −30.2%, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of mean itch scores at baseline and 16 h after treatment instillation at 3 min post-conjunctival allergen challenge (primary endpoint). Mean itch scores for alcaftadine 0.25%, olopatadine 0.2%, and placebo. *P < 0.0001 for alcaftadine and olopatadine versus placebo; **P = 0.0006 for alcaftadine versus olopatadine. P values calculated using the two-sample t test

Fig. 3.

Comparison of overall mean itch scores at baseline and 16 h after treatment instillation over all time points (3, 5, and 7 min) post-conjunctival allergen challenge. Mean itch scores for alcaftadine 0.25%, olopatadine 0.2%, and placebo. *P < 0.0001 for alcaftadine and olopatadine versus placebo; **P = 0.0390 for alcaftadine versus olopatadine. P values calculated using the repeated measures analysis of covariance model accounting for treatment and time points

Table 2.

Mean differences in ocular itch scores post-CAC at 16 h after treatment instillation

| Time point post-CAC | Difference in mean itch scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcaftadine versus placebo | Olopatadine versus placebo | Alcaftadine versus olopatadine | |

| 3 min | −1.57; P < 0.0001* | −1.20; P < 0.0001* | −0.37; P = 0.0006* |

| 5 min | −1.45; P < 0.0001* | −1.26; P < 0.0001* | −0.19; P = 0.0873* |

| 7 min | −1.17; P < 0.0001* | −1.14; P < 0.0001* | −0.03; P = 0.7751* |

| Over all time points | −1.42; P < 0.0001† | −1.19; P < 0.0001† | −0.24; P = 0.0390† |

CAC conjunctival allergen challenge

* P values calculated using two-sample t test. † P values calculated using repeated measures analysis of covariance model accounting for treatment and time

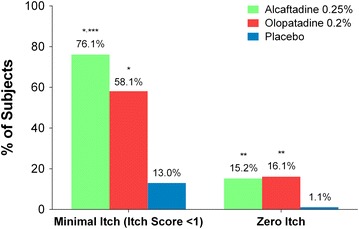

The ocular itching primary efficacy measure was further assessed by comparing the proportion of subjects in each group with minimal itch (itch score <1) and zero itch (itch score = 0). For subjects who met the criteria for minimal itch or zero itch at all three time points (3, 5, and 7 min), significantly higher proportions of subjects achieved overall minimal itch and zero itch in the alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% groups compared with the placebo group (minimal itch, P < 0.0001; zero itch, P ≤ 0.0006, for both actives versus placebo; Fig. 4). A significantly greater proportion of alcaftadine 0.25%-treated subjects achieved an itch score <1 compared with olopatadine 0.2%-treated subjects over all time points (76.1% vs. 58.1%; P = 0.0121); no significant differences were observed in the proportion of subjects achieving zero itch between the two actives (15.2% vs. 16.1%; P = 1.00; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of overall percentage of subjects with minimal itch and zero itch scores at 16 h after treatment instillation. Percentage of subjects with minimal itch (itch score <1) and zero itch for alcaftadine 0.25%, olopatadine 0.2%, and placebo at all time points post-conjunctival allergen challenge. Subjects had to meet the itch score criteria (<1 or 0) at 3, 5, and 7 min post-conjunctival allergen challenge. *P < 0.0001 for alcaftadine and olopatadine versus placebo; **P ≤ 0.0006 for alcaftadine and olopatadine versus placebo; ***P = 0.0121 for alcaftadine versus olopatadine. P values calculated using Fisher’s exact test

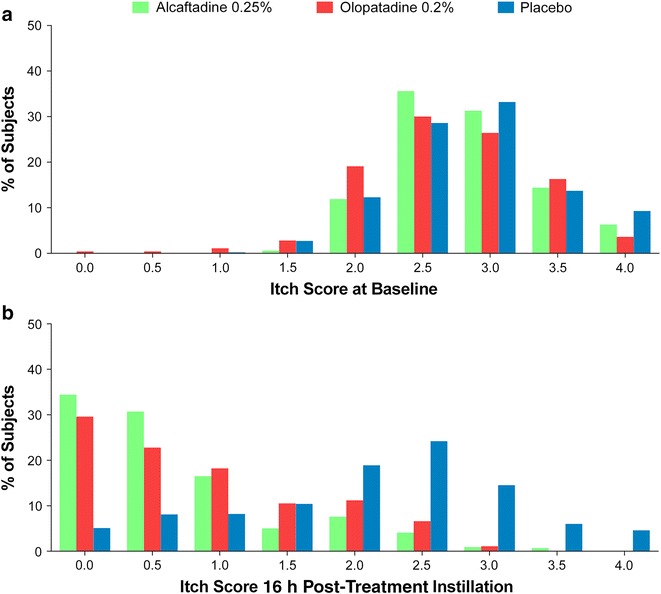

The distribution of the raw subject-reported itch scores at baseline and 16 h post-treatment instillation also was analyzed in which all itch scores of each eye were included in the analysis for all time points (3, 5, and 7 min; Fig. 5). A shift to the left in the frequencies of scores indicated improvement in both the magnitude of relief and proportion of subjects whose symptoms were alleviated. Subjects in all three treatment groups (alcaftadine 0.25%, olopatadine 0.2%, and placebo) showed a similar distribution of itch scores at baseline, with the majority of subjects reporting scores between 2.0 and 3.5 over all time points post-CAC (Fig. 5a). A significantly larger proportion of subjects who received treatment with alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% reported lower itch scores between 0 and 1.0 post-CAC compared with placebo-treated subjects 16 h post-treatment instillation. A greater leftward shift was observed in the alcaftadine group than in the olopatadine group; more subjects receiving alcaftadine 0.25% reported itch scores of 0 and 0.5 (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Distribution of itch scores at baseline (a) and 16 h after treatment instillation (b). Itch scores of each eye at baseline (untreated) and 16 h after treatment with alcaftadine 0.25%, olopatadine 0.2%, and placebo at all time points measured (3, 5, and 7 min) post-conjunctival allergen challenge

Safety

Sixteen adverse events were reported among 283 subjects comprising the safety population. A total of 11 (3.9%) subjects, four treated with alcaftadine 0.25%, five treated with olopatadine 0.2%, and two receiving placebo experienced at least one adverse event. No adverse events were considered to be related to study treatment, and no serious adverse events were reported during the course of the studies.

Discussion

Two similarly designed multicenter studies were conducted to compare the efficacy and safety of alcaftadine 0.25%, olopatadine 0.2%, and placebo in relieving ocular itch and symptoms related to allergic conjunctivitis. These are the first studies to compare the two agents approved for once-daily use for the prevention of itching associated with allergic conjunctivitis. The first study by Ackerman et al. [26] showed differences in relief of itch between alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% at the earliest time point measured post-CAC (3 min) [26]. The second study confirmed the treatment outcome differences between alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% in preventing signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis at 16 h post-treatment instillation [27, 28]. The present analysis pools these findings in a large data set and identified additional differentiation over the 3, 5, and 7 min time points.

In the pooled analysis, alcaftadine 0.25%-treated subjects experienced significantly lower mean ocular itch scores than olopatadine 0.2%-treated subjects at 3 min post-CAC (P = 0.0006). In addition, alcaftadine 0.25% ophthalmic solution also was superior to olopatadine 0.2% ophthalmic solution in reducing mean itch scores over all time points measured (3, 5, and 7 min; P = 0.0390). A significantly greater proportion of alcaftadine 0.25%-treated subjects achieved minimal itch (itch score <1) compared with olopatadine 0.2%-treated subjects over all time points (P = 0.0121). There were no statistically significant differences in the proportion of subjects with zero itch (itch score = 0). Both alcaftadine and olopatadine were superior to placebo at relieving ocular itch associated with allergic conjunctivitis in the pooled analysis.

Alcaftadine is unique among ocular antihistamines in that it exhibits antagonistic activity against H1, H2, and H4 receptors (although with lower affinity than H1 and H2) [20, 30]. The role of H4 receptors in allergic conjunctivitis has not been fully elucidated; in vitro studies suggest that histamine binding to H4 receptors mediates eosinophil chemotaxis [31]. In this pooled analysis, the distribution of subject-reported itch scores at 16 h post-treatment instillation over all time points showed an improvement with alcaftadine 0.25% relative to olopatadine in the degree of relief and the proportion of subjects whose symptoms are alleviated following allergen challenge, achieving a statistically significant greater percentage of subjects with scores of 0 or 0.5 relative to olopatadine 0.2% on a five-point scale. In addition to this greater magnitude of effect, in a previous study, alcaftadine 0.25% had a rapid onset of action as measured at 15 min post-treatment instillation, which was superior to that of olopatadine 0.1%, and sustained duration of action up to 16 h post-treatment instillation [14]. In a murine model of allergic conjunctivitis, alcaftadine demonstrated a greater effect than olopatadine on eosinophil recruitment and stability of the epithelial junctional protein, zonula occludens-1 [32]. Overall, these in vivo results suggest that differences observed clinically between alcaftadine and olopatadine may reflect a greater ability of alcaftadine to prevent allergen-activated disruption of the epithelial barriers [33].

Similar to other reports of alcaftadine and olopatadine [14, 15, 17, 26], treatment with alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% was found to be generally well tolerated. While eleven (3.9%) subjects experienced at least one adverse event, none of the adverse events were related to study treatment. In addition, there were no serious adverse events reported at any time during either study.

Limitations are inherent in any pooled analysis, though the two studies pooled in the present analysis demonstrated consistent findings across measures evaluating relief of ocular itching. In addition, both studies were conducted employing the CAC model. Additional long-term studies comparing alcaftadine and olopatadine may further elucidate differences identified in these two studies in the CAC model for allergic conjunctivitis.

Conclusion

Evidence supports the use of alcaftadine 0.25% for the prevention of itching associated with allergic conjunctivitis, a condition affecting a significant number of individuals worldwide. Compared with olopatadine 0.2% ophthalmic solution, treatment with alcaftadine 0.25% ophthalmic solution provided greater relief of ocular itching at 16 h post-administration with a similar safety profile. Additional studies are warranted to fully elucidate the underlying mechanisms responsible for the observed differences in treatment outcomes between the alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% once-daily ophthalmic solutions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA. Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Kakuri M. Omari, PhD, of Evidence Scientific Solutions, Philadelphia, PA, and funded by Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study when requested and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. The authors received no compensation related to the development of the manuscript. Article processing charges were funded by Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA. The data were presented in part at the 2014 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Annual Meeting, February 28–March 4, San Diego, CA, 2014, and the 2014 American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery Annual Symposium, April 24–29, 2014, Boston, MA.

Conflict of interest

Eugene B. McLaurin has received research support from Aciex, Acucela, Alcon, Allergan, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bausch & Lomb, Inotek Pharmaceuticals, InSite Vision, and Lexicon Pharmaceuticals. Stacey L. Ackerman has received research support from Aciex, Alcon, Allergan, and Bausch & Lomb. Joseph B. Ciolino is supported by a Career Development Award from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. and the National Eye Institute. Julia M. Williams is an employee of Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA. Linda Villanueva is an employee of Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA. David A. Hollander is an employee of Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA. Nicholas P. Marsico has no conflict to disclose related to this work.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Protocols and informed consent forms were approved by an independent review board (Alpha IRB, San Clemente, CA, USA). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Footnotes

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01470118 and #NCT01732757.

References

- 1.Mortemousque B, Fauquert JL, Chiambaretta F, Demoly P, Helleboid L, Creuzot-Garcher C, et al. Conjunctival provocation test: recommendations. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2006;29:837–846. doi: 10.1016/S0181-5512(06)73857-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leonardi A, Bogacka E, Fauquert JL, Kowalski ML, Groblewska A, Jedrzejczak-Czechowicz M, et al. Ocular allergy: recognizing and diagnosing hypersensitivity disorders of the ocular surface. Allergy. 2012;67:1327–1337. doi: 10.1111/all.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosario N, Bielory L. Epidemiology of allergic conjunctivitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11:471–476. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834a9676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaiss MS. Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: burden of disease. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007;28:393–397. doi: 10.2500/aap.2007.28.3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh K, Axelrod S, Bielory L. The epidemiology of ocular and nasal allergy in the United States, 1988–1994. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:778.e6–783.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Björksten B, Clayton T, Ellwood P, Stewart A, Strachan D, ISAAC Phase III Study Group Worldwide time trends for symptoms of rhinitis and conjunctivitis: phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:110–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collum L, Kilmartin DJ. Acute Allergic Conjunctivitis. In: Abelson MB, editor. Allergic diseases of the eye. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co; 2000. pp. 108–132. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonardi A, De Dominicis C, Motterle L. Immunopathogenesis of ocular allergy: a schematic approach to different clinical entities. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7:429–435. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3282ef8674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ono SJ, Abelson MB. Allergic conjunctivitis: update on pathophysiology and prospects for future treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abelson MB, Udell IJ. H2-receptors in the human ocular surface. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:302–304. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010304018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bielory L, Ghafoor S. Histamine receptors and the conjunctiva. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:437–440. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000183113.63311.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakano Y, Takahashi Y, Ono R, Kurata Y, Kagawa Y, Kamei C. Role of histamine H4 receptor in allergic conjunctivitis in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;608:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zampeli E, Thurmond RL, Tiligada E. The histamine H4 receptor antagonist JNJ7777120 induces increases in the histamine content of the rat conjunctiva. Inflamm Res. 2009;58:285–291. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-8245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greiner JV, Edwards-Swanson K, Ingerman A. Evaluation of alcaftadine 0.25% ophthalmic solution in acute allergic conjunctivitis at 15 minutes and 16 hours after instillation versus placebo and olopatadine 0.1% Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:87–93. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S15379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torkildsen G, Shedden A. The safety and efficacy of alcaftadine 0.25% ophthalmic solution for the prevention of itching associated with allergic conjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:623–631. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.548797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lastacaft® (alcaftadine ophthalmic solution) 0.25% Prescribing Information, Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA. 2011. URL: http://www.allergan.com/assets/pdf/lastacaft_pi.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- 17.Abelson MB, Spangler DL, Epstein AB, Mah FS, Crampton HJ. Efficacy of once-daily olopatadine 0.2% ophthalmic solution compared to twice-daily olopatadine 0.1% ophthalmic solution for the treatment of ocular itching induced by conjunctival allergen challenge. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32:1017–1022. doi: 10.1080/02713680701736558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scoper SV, Berdy GJ, Lichtenstein SJ, Rubin JM, Bloomenstein M, Prouty RE, et al. Perception and quality of life associated with the use of olopatadine 0.2% (Pataday) in patients with active allergic conjunctivitis. Adv Ther. 2007;24:1221–1232. doi: 10.1007/BF02877768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pataday® (olopatadine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution) 0.2% Prescribing Information, Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX. 2010. URL: http://ecatalog.alcon.com/PI/Pataday_us_en.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- 20.Wade L, Bielory L, Rudner S. Ophthalmic antihistamines and H1–H4 receptors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:510–516. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328357d3ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abelson MB, Chambers WA, Smith LM. Conjunctival allergen challenge. A clinical approach to studying allergic conjunctivitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:84–88. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070030090035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abelson MB, Loeffler O. Conjunctival allergen challenge: models in the investigation of ocular allergy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2003;3:363–368. doi: 10.1007/s11882-003-0100-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abelson MB. Evaluation of olopatadine, a new ophthalmic antiallergic agent with dual activity, using the conjunctival allergen challenge model. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81:211–218. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62814-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abelson MB, Gomes P, Crampton HJ, Schiffman RM, Bradford RR, Whitcup SM. Efficacy and tolerability of ophthalmic epinastine assessed using the conjunctival antigen challenge model in patients with a history of allergic conjunctivitis. Clin Ther. 2004;26:35–47. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(04)90004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abelson MB, Torkildsen GL, Williams JI, Gow JA, Gomes PJ. McNamara TR; Bepotastine Besilate Ophthalmic Solutions Clinical Study Group. Time to onset and duration of action of the antihistamine bepotastine besilate ophthalmic solutions 1.0% and 1.5% in allergic conjunctivitis: a phase III, single-center, prospective, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, conjunctival allergen challenge assessment in adults and children. Clin Ther. 2009;31:1908–1921. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ackerman S, D’Ambrosio F., Jr Greiner JV, Villanueva L, Ciolino JB, Hollander DA. A multicenter evaluation of the efficacy and duration of action of alcaftadine 0.25% and olopatadine 0.2% in the conjunctival allergen challenge model. J Asthma Allergy. 2013;6:43–52. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S38671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLaurin EB, Marsico NP, Ciolino JB, Williams JM, Hollander DA. Alcaftadine 0.25% versus olopatadine 0.2% in the prevention of ocular itching in allergic conjunctivitis. Presented at: American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 2013 Annual Scientific Meeting; November 7–11, 2013; Baltimore, MD.

- 28.McLaurin EB, Marsico NP, Ciolino JB, Williams JM, Hollander DA. Alcaftadine 0.25% versus olopatadine 0.2% in prevention of ocular itching due to allergic conjunctivitis in a CAC™ model. Presented at: American Academy of Ophthalmology 2013 Annual Meeting; November 16–19, 2013; New Orleans, LA.

- 29.Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, MedDRA MSSO, McLean, VA. 2013. URL: http://www.meddra.org/. Accessed February 28, 2013.

- 30.Namdar R, Valdez C. Alcaftadine: a topical antihistamine for use in allergic conjunctivitis. Drugs Today (Barc). 2011;47:883–890. doi: 10.1358/dot.2011.47.12.1709243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ling P, Ngo K, Nguyen S, Thurmond RL, Edwards JP, Karlsson L, et al. Histamine H4 receptor mediates eosinophil chemotaxis with cell shape change and adhesion molecule upregulation. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:161–171. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ono SJ, Lane K. Comparison of effects of alcaftadine and olopatadine on conjunctival epithelium and eosinophil recruitment in a murine model of allergic conjunctivitis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2011;5:77–84. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S15788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Contreras-Ruiz L, Schulze U, García-Posadas L, Arranz-Valsero I, Lopez-Garcia A, Paulsen F, et al. Structural and functional alteration of corneal epithelial barrier under inflammatory conditions. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:971–981. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.700756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.