Abstract

Introduction

The objective of this study was to compare the efficacy and safety of olopatadine versus epinastine in healthy Japanese adults with a history of allergic conjunctivitis to Japanese cedar pollen.

Methods

This Phase IV double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial comprised three clinical visits over 30 days. Screening tests were performed to identify subjects with a history of allergic conjunctivitis to Japanese cedar pollen in terms of skin sensitivity and positive bilateral reactions to a conjunctival allergen challenge (CAC) with Japanese cedar pollen at Visit 1, and confirmation by a positive bilateral CAC reaction at Visit 2. At Visit 3, the subjects were randomized to receive one drop of olopatadine HCl ophthalmic solution 0.1% (olopatadine) in the left or right eye (1:1 ratio). All subjects received one drop of epinastine HCl ophthalmic solution 0.05% (epinastine) in the contralateral eye as an active control. Five min later, the subjects underwent bilateral CAC tests with one drop of the allergen solution at the concentration that elicited positive reactions at Visits 1 and 2. Efficacy outcomes included the severity of ocular itching at 5, 7, and 15 min and the severity of conjunctival hyperemia at 7, 15, and 20 min after the CAC test, as graded by the investigator by biomicroscopy.

Results

Fifty people participated in this study (25 per group). Olopatadine significantly reduced ocular itching at 7 and 15 min (both p < 0.05) and conjunctival hyperemia at 7 and 20 min (p = 0.0010 and p < 0.05, respectively) after allergen exposure compared with epinastine. There were no adverse events for either treatment.

Conclusion

The results of this single-dose study suggest that olopatadine is superior to epinastine in terms of suppressing ocular itching and hyperemia induced by Japanese cedar pollen during CAC tests. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings in real-life settings.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-014-0156-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Allergic conjunctivitis, Conjunctival allergen challenge, CAC, Conjunctival hyperemia, Epinastine, Itching, Japanese cedar pollen, Olopatadine, Ophthalmology

Introduction

Seasonal allergic conjunctivitis (SAC) is the most common form of ocular allergy and is thought to affect 15–20% of people worldwide [1, 2]. SAC is associated with several transient symptoms, especially ocular itching, hyperemia, and chemosis. These symptoms typically occur during seasonal elevations in ambient pollen concentrations [1, 2]. The pathophysiology of SAC is primarily driven by the release of histamine from mast cells and the binding of histamine to topical H1 receptors [3]. Current treatments include multi-target drugs with anti-histamine and anti-inflammatory properties that typically suppress the symptoms of SAC and stabilize mast cell activity [4].

Japanese cedar pollinosis is a common disease with an age-adjusted estimated prevalence of 19.4% in Japan [5], and is considered to be a national affliction [6]. Japanese cedar pollen is released in early February and March, and is the most abundant type of pollen in early spring in Japan [5, 6]. Japanese cedar pollinosis is characterized by nasal symptoms such as sneezing and rhinorrhea, as well as severe ocular itching [6]. Several topical ophthalmic solutions with anti-histamine and anti-inflammatory activities that stabilize mast cell activity are now available in Japan, including ketotifen fumarate 0.05% (ketotifen), levocabastine hydrochloride 0.05% (levocabastine), epinastine hydrochloride 0.05% (epinastine), and olopatadine hydrochloride 0.1% (olopatadine) [7]. Oral preparations of epinastine and olopatadine have also been developed and provide systemic relief from allergic disease, although the ophthalmic effects of these preparations have not been extensively evaluated.

Prior studies have demonstrated that olopatadine is more effective than epinastine [8], levocabastine [9], and ketotifen [10] in terms of alleviating the symptoms after a conjunctival allergen challenge (CAC) test in humans. To our knowledge, however, no studies have compared the efficacy of these agents in terms of reducing allergic conjunctivitis symptoms caused by Japanese cedar pollen. Therefore, we performed a randomized controlled clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of olopatadine versus epinastine in healthy Japanese adults with a history of allergic conjunctivitis induced by Japanese cedar pollen using a version of the CAC model (Ora-CAC).

Methods

We performed a single-center (Biochemical Research Center, Kitasato Institute Hospital, Tokyo, Japan), double-blind, three-visit, randomized study to compare the efficacy and safety of olopatadine and epinastine for treating allergic conjunctivitis induced by Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica). This study was performed in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the Ethical Guideline for Clinical Studies stipulated by the Minister of Health, Labor and Welfare (Japan), and the guidelines of the Pharmaceutical and Medical Devices Agency (Japan). The study was approved by the institutional review board at Kitasato Institute Hospital. The study was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network clinical trial registry (identifier: UMIN000013943). An independent contract research organization (Ora, Inc, Boston, MA, USA, and Ora Japan KK, Osaka, Japan) designed the study and provided study oversight. Subject recruitment and study site coordination were performed by Kitasato Institute.

Procedures

The Ora-CAC model, which is based on a method described by Abelson et al. [11], was used. In brief, Japanese cedar allergen was prepared by Ora staff using standard proprietary methods. Serial dilutions were made and tested on volunteers in an escalating dose fashion at Visit 1. Confirmatory CAC with the highest concentration of allergen determined previously at Visit 1 was done at Visit 2. This was the same concentration used at Visit 3. Following this standard protocol, the study comprised three clinical visits with approximately 15 days between each visit. At Visit 1 (Day −30 ± 3), potential subjects underwent screening tests to determine their eligibility. First, subjects were tested for skin sensitivity to Japanese cedar pollen by injecting a small amount of cedar pollen and saline as a control using a Bifurcated Needle™ (Tokyo M. I. Company, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Candidates with negative skin reactions to Japanese cedar pollen were excluded from the study. Candidates with positive skin reactions (wheal size ≥5 mm, erythema size ≥15 mm, or wheal diameter at least twice the diameter of the negative control) at Visit 1 underwent subsequent titration CAC tests. In these tests, the subjects were bilaterally administered with Japanese cedar pollen (serially diluted in buffered saline) into the conjunctival cul-de-sac. After each dose, the severity of the allergic reaction was assessed in terms of scores for itching and hyperemia in the conjunctival vessel bed. A positive CAC result was defined as scores of ≥2 for itching (using a 5-point scale with 0.5-unit increments, where 0 = none and 4 = incapacitating itching) and ≥2 for hyperemia (using a 5-point scale with 0.5-unit increments, where 0 = none and 4 = extremely severe hyperemia) in both eyes within 10 min of administration. If no response was observed at 10 min after administration, the subject was administered with a higher concentration of the solubilized allergen, which was repeated until a positive test result was observed (scores of ≥2 for itching and ≥2 for hyperemia). The subjects assessed and graded ocular itching before and after the CAC. The investigator used biomicroscopy to grade conjunctival hyperemia. The findings of these assessments were used to assess the subject’s eligibility. Subjects who did not satisfy the criteria for a positive CAC response to Japanese cedar pollen were excluded from the study.

At Visit 2 (Day −15 ± 3), the subjects underwent a bilateral CAC in which one drop of Japanese cedar pollen solution was administered at the concentration that elicited a positive reaction at Visit 1. The subjects assessed itching before and at 5, 7, and 15 min after the CAC, as well as eyelid swelling and tearing at 7, 15, and 20 min after the CAC. The investigator assessed conjunctival hyperemia at 7, 15, and 20 min after the CAC. Subjects with negative results were excluded from the study. At Visit 2, a positive CAC reaction was defined as (1) itching scores ≥2 at 5 min and at either 7 or 15 min after administration, and (2) hyperemia scores ≥2 in the conjunctival vessel bed at two or more times (5, 7, or 15 min).

At Visit 3 (Day 1), all of the subjects with positive allergen reactivity tests at Visit 1 and Visit 2 who satisfied the eligibility criteria returned to the clinic and were randomized to receive one drop of olopatadine (olopatadine HCl ophthalmic solution 0.1%, PATANOL® from Alcon Laboratories) in the left or right eye (1:1 ratio) according to the assignment schedule prepared by Ora Inc.; all subjects received one drop of epinastine (epinastine HCl ophthalmic solution 0.05%, ALESION from Santen Pharmaceutical Co.) in the contralateral eye as an active control. Both study drugs were used at their marketed concentrations. All study drugs were administered by a trained physician in a double-blind manner. To ensure successful blinding, Kitasato Institute purchased the study drugs and re-labeled them as A and B according to the treatment assignment. The investigator who administered the study drugs was not involved in the investigator-based assessments of hyperemia. Administration of the study drugs was confirmed by a second investigator. Five min after administration of the study drugs, the subjects underwent a bilateral CAC in which one drop of the allergen solution was administered to each eye at the concentration that elicited positive reactions at Visits 1 and 2. The subjects assessed itching at 5, 7, and 15 min after administration of the allergen, and an investigator blinded to the study group assessed conjunctival hyperemia at 7, 15, and 20 min.

Study Population

The subjects comprised healthy Japanese males or females aged ≥20 years living in Japan with a history of allergic conjunctivitis. Volunteers were recruited and registered as members. These volunteers received screening tests as described below. Key inclusion criteria included a positive skin test reaction to Japanese cedar pollen at Visit 1, and positive bilateral CAC reactions to Japanese cedar pollen at both Visits 1 and 2. The main exclusion criteria included clinically active allergic conjunctivitis (because CAC should be conducted during the season without the target pollens), active ocular infection, preauricular lymphadenopathy, any ocular condition that could affect the subject’s safety or study parameters (e.g., narrow angle glaucoma requiring medication or laser treatment, clinically significant blepharitis, follicular conjunctivitis, iritis, pterygium, or dry eye), or histories of vernal keratoconjunctivitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis, or recent ocular surgery and/or refractive surgery. All subjects provided written informed consent at Visit 1.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Efficacy Endpoints

The efficacy of the study drugs was assessed in terms of itching and hyperemia scores at pre-specified times after administering the allergen in the CAC on Visit 3. The primary efficacy outcome was ocular itching at 7 ± 1 min after administering the allergen. Ocular itching in both eyes was evaluated by the subject using a 5-point scale with 0.5-unit increments, where 0 = none and 4 = incapacitating itching. The main secondary efficacy outcome was conjunctival hyperemia at 20 ± 1 min. The investigator evaluated conjunctival hyperemia in both eyes using biomicroscopy and graded the severity of hyperemia using a 5-point scale with 0.5-unit increments, where 0 = none and 4 = extremely severe hyperemia (large, numerous, dilated blood vessels characterized by unusually severe deep red color regardless of chemosis and involving the entire vessel bed). An ophthalmologist evaluated redness and chemosis scores. The redness scale used was an Ora standard proprietary scale with photographs used in Ora-CAC studies [11]. The scale is not for widespread distribution. Ophthalmologists were trained by Ora and had scales available for reference when evaluating redness. The primary and secondary efficacy endpoints were chosen based on the physiological responses to allergen instillation [12]. For itching, which is caused by neuronal activation, the peak was reported to occur about 5 min after instillation, while for conjunctival hyperemia, clinically significant redness is found at about 7 min and the peak usually occurs between 15 and 20 min after instillation. The results of a previous study suggested that the responses to Japanese cedar pollen in Japanese subjects are delayed [12] compared with the responses to other allergens in non-Japanese subjects [8]. Therefore, we selected 7 min to determine the peak level of itching and, because the onset of redness shows a flatter time profile, we assessed conjunctival hyperemia at 20 min after instillation.

Supportive efficacy outcomes were ocular itching at 5 ± 1 and 15 ± 1 min and conjunctival hyperemia at 7 ± 1 and 15 ± 1 min; ciliary hyperemia, episcleral hyperemia, chemosis, and eyelid swelling scores at 7 ± 1, 15 ± 1, and 20 ± 1 min; and the proportions of subjects with self-reported tearing or mucous discharge at 7 ± 1, 15 ± 1, and 20 ± 1 min. Ciliary hyperemia and episcleral hyperemia in both eyes were evaluated by investigator via biomicroscopy using the same 5-point scale (0–4) used for conjunctival hyperemia (Table 1). Chemosis was evaluated by the investigator using a 5-point scale with 0.5-unit increments, where 0 = none and 4 = extremely severe. Eyelid swelling was assessed by the subjects at 7 ± 1, 15 ± 1, and 20 ± 1 min using a 4-point scale (without 0.5-unit increments), where 0 = none and 3 = severe. Subject-assessed tearing and investigator-assessed ocular mucous discharge at 7 ± 1, 15 ± 1, and 20 ± 1 min were reported as either absent or present in either eye. The investigator who assessed conjunctival hyperemia and supportive endpoints was unaware of the study group.

Table 1.

Results of the supportive efficacy endpoints

| Variable | Mean scores | Difference (olopatadine−epinastine) | p a | p b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olopatadine | Epinastine | ||||

| n | 50 | 50 | |||

| Ciliary hyperemia | |||||

| Before the CAC test | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 | – | – |

| 7 ± 1 min | 0.13 ± 0.28 | 0.19 ± 0.32 | −0.06 | 0.0916 | 0.0832 |

| 15 ± 1 min | 0.31 ± 0.45 | 0.39 ± 0.52 | −0.08 | 0.0978 | 0.0882 |

| 20 ± 1 min | 0.41 ± 0.53 | 0.49 ± 0.63 | −0.08 | 0.1720 | 0.1594 |

| Episcleral hyperemia | |||||

| Before the CAC test | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 | – | – |

| 7 ± 1 min | 0.14 ± 0.30 | 0.20 ± 0.32 | −0.06 | 0.0328 | 0.0324 |

| 15 ± 1 min | 0.48 ± 0.64 | 0.56 ± 0.67 | −0.08 | 0.1319 | 0.1319 |

| 20 ± 1 min | 0.60 ± 0.76 | 0.74 ± 0.80 | −0.14 | 0.0742 | 0.0751 |

| Chemosis | |||||

| Before the CAC test | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 | – | – |

| 7 ± 1 min | 0.11 ± 0.31 | 0.18 ± 0.35 | −0.07 | 0.0182 | 0.0180 |

| 15 ± 1 min | 0.43 ± 0.49 | 0.47 ± 0.49 | −0.04 | 0.4171 | 0.4197 |

| 20 ± 1 min | 0.52 ± 0.53 | 0.62 ± 0.58 | −0.10 | 0.0738 | 0.0768 |

| Eyelid swelling | |||||

| Before the CAC test | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 | – | – |

| 7 ± 1 min | 0.04 ± 0.20 | 0.02 ± 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.4024 | 0.3222 |

| 15 ± 1 min | 0.08 ± 0.27 | 0.12 ± 0.39 | −0.05 | 0.2400 | 0.3222 |

| 20 ± 1 min | 0.10 ± 0.30 | 0.22 ± 0.46 | −0.13 | 0.0421 | 0.0569 |

| Tearing, yes | |||||

| Before the CAC test | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | – | – |

| 7 ± 1 min | 2 (4.0) | 2 (4.0) | – | – | 1.000 |

| 15 ± 1 min | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | – | – | 1.000 |

| 20 ± 1 min | 1 (2.0) | 3 (6.0) | – | – | 0.1573 |

| Mucous discharge, yes | |||||

| Before the CAC test | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – | – | – |

| 7 ± 1 min | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | – | – | 1.000 |

| 15 ± 1 min | 3 (6.0) | 4 (8.0) | – | – | 0.5637 |

| 20 ± 1 min | 2 (4.0) | 4 (8.0) | – | – | 0.3173 |

Values are mean ± standard deviation or n (%) for the intent-to-treat population with observed data only

CAC conjunctival allergen challenge

aAnalysis of covariance

bPaired t test or McNemar test (tearing and mucous discharge)

Safety Endpoints

Conjunctival allergen challenge was intended to induce allergic conjunctivitis in volunteers. An adverse event can therefore be any unfavorable and unintended sign (e.g., an abnormal laboratory finding), symptom, or disease occurring after the patient has been administered any drug under this protocol, without any judgment about causality. Safety evaluations included best-corrected visual acuity before the CAC at Visits 1–3; slit lamp biomicroscopy before and after the CAC at all Visits 1–3; physical examination (auscultation and percussion); vital signs before the CAC at Visits 1 and 3; and undilated fundoscopy after the CAC at Visits 1 and Visit 3. Subjects were surveyed about adverse events after the CAC at Visit 1 and before and after the CACs at Visits 2 and 3.

Statistical Analyses

The sample size was calculated based on the itching scores reported in an earlier study that compared olopatadine with epinastine using the CAC test [8]. Fifty evaluable subjects were needed to achieve 86% power with two-sided α = 0.05 to show a statistically significant difference between the two treatments.

The primary efficacy analysis was conducted in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method to impute missing data. Analyses of secondary outcomes and sensitivity analyses were performed on the ITT population with observed data only (ODO). Symptom scores were summarized using descriptive statistics [mean, standard deviation (SD), sample number (n), median, and range] by treatment at each time point for primary and secondary endpoints. Treatment means and treatment differences (olopatadine−epinastine) were estimated with 95% confidence intervals using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with the mean score after the CAC at Visit 2 (Day −15 ± 3) for each eye as a covariate. This analysis was confirmed in supportive analysis using the paired t test. Hypothesis testing of the main secondary variable was to follow the primary analysis if the primary null hypothesis was rejected. Family-wise error was controlled at 2.5% (one-sided) between the primary and main secondary analyses. Secondary efficacy variables were analyzed using identical methods to the primary efficacy variable in the ITT population with ODO. Safety variables were analyzed descriptively in all randomized subjects according to the assigned treatment, when appropriate. No statistical comparisons were made for safety variables. Data were entered into Microsoft Excel version 14.0.7128.500 (64-bit), Redmond, WA, USA. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA, for all of our analyses.

Results

Study Subjects

Between December 2013 and January 2014, 103 subjects were initially screened of which 22 did not meet the eligibility criteria at Visit 1, 24 did not meet the eligibility at Visit 2, and 7 were withdrawn because of the stated enrollment capacity. Therefore, 50 subjects attended the clinic at Visit 3 and were included in the efficacy (ITT set) and safety analyses. There were 28 males and 22 females. The mean ± SD age was 33.3 ± 9.2 years (Table 2). The subjects were equally randomized into two groups and received olopatadine in the right or left eye (n = 25 per group); epinastine was administered into the contralateral eye. None of the subjects withdrew from the study at Visit 3. Therefore, all 50 subjects were included in the ITT, per protocol (PP), and safety populations. In all subjects, the study drugs were correctly administered in the assigned eyes. Table 3 shows the scores for ocular itching and conjunctival hyperemia at Visit 2.

Table 2.

Subject characteristics

| Variable | Treatment (left eye/right eye) | All subjects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olopatadine/epinastine | Epinastine/olopatadine | ||

| n | 25 | 25 | 50 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 14 (56.0) | 14 (56.0) | 28 (56.0) |

| Female | 11 (44.0) | 11 (44.0) | 22 (44.0) |

| Age, years | |||

| Mean ± SD | 33.1 ± 9.5 | 33.5 ± 9.1 | 33.3 ± 9.2 |

| Range | 20–49 | 21–53 | 20–53 |

SD standard deviation

Table 3.

Ocular itching and conjunctival hyperemia scores at Visit 2

| Variable | Mean scores | |

|---|---|---|

| Olopatadine | Epinastine | |

| n | 50 | 50 |

| Ocular itching | ||

| Before the CAC test | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 5 ± 1 min | 2.52 ± 0.50 | 2.53 ± 0.49 |

| 7 ± 1 min | 2.71 ± 0.53 | 2.73 ± 0.50 |

| 15 ± 1 min | 2.75 ± 0.65 | 2.78 ± 0.60 |

| Conjunctival hyperemia | ||

| Before the CAC test | 0.03 ± 0.12 | 0.03 ± 0.12 |

| 7 ± 1 min | 2.19 ± 0.63 | 2.19 ± 0.64 |

| 15 ± 1 min | 2.79 ± 0.64 | 2.81 ± 0.67 |

| 20 ± 1 min | 2.83 ± 0.73 | 2.82 ± 0.73 |

Values are mean ± standard deviation for the intent-to-treat population with observed data only

CAC conjunctival allergen challenge

Primary Efficacy Endpoint

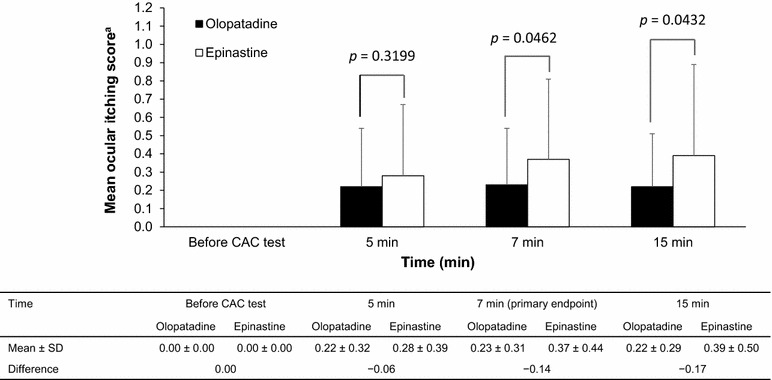

The primary efficacy endpoint was the mean itching score at 7 ± 1 min after allergen administration in the CAC at Visit 3. As shown in Fig. 1, the mean ± SD itching score in the ITT population was 0.23 ± 0.31 in olopatadine-treated eyes compared with 0.37 ± 0.44 in epinastine-treated eyes. The treatment difference of −0.14 in favor of olopatadine was statistically significant based on ANCOVA (p = 0.0462). The difference was also significant using the paired t test (p = 0.0377). Identical results were obtained when the ITT population was used with ODO.

Fig. 1.

Effects of olopatadine and epinastine on the mean ocular score at 5, 7, and 15 min after allergen administration (Japanese cedar pollen) in the conjunctival allergen challenge test. The primary efficacy outcome was the mean ocular itching score at 7 min. The analysis was not adjusted for multiplicity at 5 or 15 min. Values are mean ± standard deviation. Treatment differences and p values were calculated by analysis of covariance. aMean ocular score was assessed using a 5-point scale with 0.5-unit increments ranging from 0 to 4. CAC conjunctival allergen challenge, SD standard deviation

Secondary Efficacy Endpoint

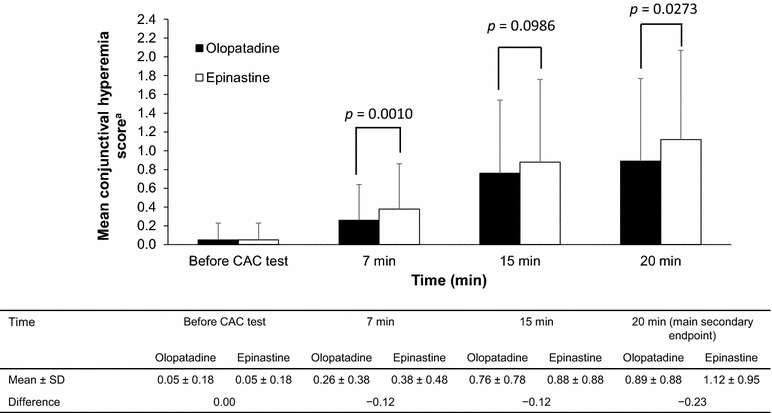

The secondary efficacy endpoint was conjunctival hyperemia at 20 ± 1 min after allergen administration in the CAC at Visit 3. As shown in Fig. 2, the mean ± SD conjunctival hyperemia scores were 0.89 ± 0.88 and 1.12 ± 0.95 for olopatadine and epinastine, respectively. The treatment difference of −0.23 units in favor of olopatadine was statistically significant based on ANCOVA (p = 0.0273). The difference was also significant with the paired t test (p = 0.026). Identical results were obtained when the ITT population was used with ODO.

Fig. 2.

Effects of olopatadine and epinastine on the conjunctival hyperemia scores at 7, 15, and 20 min after allergen administration (Japanese cedar pollen) in the conjunctival allergen challenge test. Hypothesis testing of the main secondary variable (conjunctival hyperemia at 20 min) followed the primary analysis because the primary null hypothesis (ocular itching at 7 min) was rejected. Family-wise error was controlled at 2.5% (one-sided) between the primary and main secondary analyses. The analysis was not adjusted for multiplicity at 7 or 15 min. Values are mean ± standard deviation. Treatment differences and p values were calculated by analysis of covariance. aThe conjunctival hyperemia score was assessed using a 5-point scale with 0.5-unit increments ranging from 0 to 4. CAC conjunctival allergen challenge, SD standard deviation

Supportive Efficacy Outcomes

In terms of supportive efficacy endpoints, the mean ± SD ocular itching scores in the olopatadine- and epinastine-treated eyes (ITT population with ODO) were 0.22 ± 0.32 and 0.28 ± 0.39, respectively, at 5 ± 1 min, and were 0.22 ± 0.29 and 0.39 ± 0.50, respectively, at 15 ± 1 min. The treatment difference was −0.06 at 5 ± 1 min based on ANCOVA (p = 0.3199) or the paired t test (p = 0.2934). However, the treatment difference was −0.17 in favor of olopatadine at 15 ± 1 min based on ANCOVA (p = 0.0432) and the paired t test (p = 0.0394).

The mean ± SD conjunctival hyperemia scores in the olopatadine- and epinastine-treated eyes (ITT population with ODO) were 0.26 ± 0.38 and 0.38 ± 0.48, respectively, at 7 ± 1 min, and were 0.76 ± 0.78 and 0.88 ± 0.88, respectively, at 15 ± 1 min. The treatment difference was −0.12 at 7 ± 1 min based on ANCOVA (p = 0.0010) and the paired t test (p = 0.0008). The treatment difference was −0.12 at 15 ± 1 min based on ANCOVA (p = 0.0986) and the paired t test (p = 0.0008).

The mean ± SD episcleral hyperemia scores in the olopatadine- and epinastine-treated eyes (ITT population with ODO) were 0.14 ± 0.30 and 0.20 ± 0.32, respectively, at 7 ± 1 min. The treatment difference was −0.06 at 7 ± 1 min based on ANCOVA (p = 0.0328) and the paired t test (p = 0.0324).

The mean ± SD chemosis scores in the olopatadine- and epinastine-treated eyes (ITT population with ODO) were 0.11 ± 0.31 and 0.18 ± 0.35, respectively, at 7 ± 1 min. The treatment difference was −0.07 at 7 ± 1 min based on ANCOVA (p = 0.0182) and the paired t test (p = 0.018).

There were no differences in ciliary hyperemia or the proportions of subjects with self-reported tearing or mucous discharge between the two treatments at any of the measurement times

Safety

There were no adverse events during the study. Furthermore, there were no abnormal findings in slit lamp biomicroscopy, undilated fundoscopy, or physical examination at any visit. There were no significant changes in visual acuity or vital signs between Visits 1 and 3. None of the subjects withdrew from the study because of adverse events.

Discussion

In this study, Japanese patients with a history of allergic conjunctivitis to Japanese cedar pollen underwent a single CAC test with exposure to Japanese cedar pollen as the allergen. We found that administration of olopatadine significantly reduced self-assessed ocular itching at 7 min (the primary endpoint) and investigator-assessed conjunctival hyperemia at 20 min (the main secondary endpoint) compared with epinastine without apparent safety concerns. These results support the use of olopatadine for the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis caused by Japanese cedar pollen. In a similarly designed study, Abelson and Greiner [9] performed CAC tests in 68 subjects and reported that olopatadine 0.1% significantly reduced itching and redness compared with levocabastine 0.05%. The authors also reported that olopatadine was more tolerable than levocabastine in terms of reduced discomfort following administration. In another study in which 32 subjects underwent CAC tests, Berdy et al. [10] reported that olopatadine 0.1% was more effective in reducing ocular itching than ketotifen fumarate 0.025% while causing less ocular discomfort. They also found that olopatadine was preferred over ketotifen by approximately three times as many patients. In addition, Lanier et al. [8] reported that olopatadine 0.1% was more effective than epinastine 0.05% in controlling allergic symptoms induced by a CAC test. Taken together, the results of these studies support the use of olopatadine 0.1% as an effective treatment for preventing allergic conjunctivitis and other ocular allergic symptoms. However, data should be interpreted with caution because there was no negative control group treated with physiological saline.

In these earlier studies, the authors tested the efficacy of ocular solutions using standardized allergens in CAC tests, but did not include Japanese cedar. Japanese cedar pollinosis is thought to affect more than 19.4% of the Japanese population [5], and may have significant clinical and economic effects. It presents with nasal symptoms such as sneezing and rhinorrhea, as well as severe ocular itching. So far, however, very few studies have sought to identify options for treating this allergic condition. Based on prior studies, we hypothesized that olopatadine would alleviate the severe symptoms of Japanese cedar pollinosis, especially itching. Indeed, the results of this study revealed that olopatadine was associated with significantly weaker allergic reactions in terms of itching and conjunctival hyperemia compared with an alternative active control (epinastine).

Olopatadine is also available as an oral drug for treating systemic and non-ocular allergic conditions. An earlier study compared the efficacy and safety of oral olopatadine and fexofenadine for treating the nasal symptoms of Japanese cedar pollinosis [13]. The authors reported that that olopatadine significantly improved nasal symptoms (nasal congestion, sneezing, and nasal discharge) and activity impairment compared with fexofenadine after exposure to Japanese cedar pollen in an environmental exposure unit. The results of that study and of our study highlight that olopatadine is an effective treatment for the nasal and ocular symptoms of Japanese cedar pollinosis, although a combination of oral and ophthalmic treatment may be required to target all of the symptoms.

The reasons why olopatadine showed superior efficacy (itching and redness relief) to epinastine in this study and earlier studies remain to be elucidated. One possible explanation is that the two drugs show different affinities for histamine receptors in the conjunctiva, important targets for treating allergic conjunctivitis and related allergic ocular diseases [14]. Olopatadine was reported to have a mixed antagonistic profile (competitive and noncompetitive inhibition) against histamine H1 receptors [15], whereas epinastine is a competitive inhibitor. Accordingly, olopatadine exhibited the greatest inhibitory effects among the anti-histamines tested in that study, acting in a concentration-dependent manner. Another possibility is that olopatadine also has anti-inflammatory effects, which include suppression of interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 production by conjunctival epithelial cells, by inhibiting a variety of histamine-related signaling pathways [16]. Olopatadine also has greater effects on mast cell stabilization than epinastine [17, 18].

Some limitations of this study must be mentioned. In particular, the efficacy of the study drugs was assessed at a single visit after a single exposure to Japanese cedar pollen in a CAC test. Although the procedure is useful for examining the efficacy of drugs against allergic reactions induced by a specific allergen, the results of this study may differ if exposure occurs for a longer time or if the drug is administered at different effective concentrations relative to the allergen concentration used in the CAC. In addition, because of the approach used in the present study, we could not examine the cumulative effects of exposure to the allergen or the effects of treatment for several consecutive days or weeks, which might be required in real-life settings. It is also important to consider that the results may not apply to allergic conjunctivitis caused by other common allergens. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the concentrations of the olopatadine (0.1%) and epinastine (0.05%) solutions differed. Although these are the marketed solutions, the lower concentration of epinastine may have led to lower concentrations in the conjunctiva, limiting its efficacy. Therefore, to directly compare the pharmacologic activities of ophthalmic solutions, future studies could use solutions containing equivalent concentrations of the active drugs to avoid this confounding factor. Nevertheless, the current study allowed us to compare the efficacies of the marketed products themselves.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that olopatadine 0.1% is more effective than epinastine 0.05% at reducing the symptoms of Japanese cedar pollen-induced allergic conjunctivitis in CAC tests, a short-term efficacy evaluation system. Prospective randomized controlled trials in real-life settings are needed to confirm these results and the efficacy and safety of longer term administration of olopatadine.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study were provided by Alcon Japan Ltd. Ora, Inc. developed the protocol, prepared the allergens, provided study oversight, monitored the patients, conducted data analysis and interpretation, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. The authors would like to thank Springer Healthcare and ND Smith for providing English-language editing, which was funded by Alcon Japan Ltd. All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

Atsuki Fukushima has received compensation from Alcon Japan for his work drafting and reviewing the manuscript. Atsuki Fukushima has also received lecture fees from Alcon Japan, Santen Pharmaceutical, Senju Pharmaceutical, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Kissei Pharmaceuticals, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin. Nobuyuki Ebihara has received lecture fees from Alcon Japan, Santen Pharmaceutical, Senju Pharmaceutical, Kissei Pharmaceuticals, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

List of investigators

Yoshinori Yamada (Bio Medical Research Center, Kitasato University, Kitasato Institute Hospital, Tokyo, Japan), Hiroshi Fujishima (Department of Ophthalmology, Tsurumi University School of Dental Medicine, Yokohama, Japan), Murat Dogru (Department Ophthalmology, Ichikawa Hospital, Ichikawa, Japan and Department Ophthalmology, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan), Junko Ogawa (Department Ophthalmology, Kitasato University, Kitasato Institute Hospital, Tokyo, Japan), Masatora Ogata (Department Ophthalmology, Kitasato University, Kitasato Institute Hospital, Tokyo, Japan), Motoko Kawashima (Department Ophthalmology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan), and Mariko Sasaki (Department Ophthalmology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: University Hospital Medical Information Network clinical trial registry identifier: UMIN000013943.

References

- 1.Abelson MB, George MA, Garofalo C. Differential diagnosis of ocular allergic disorders. Ann Allergy. 1993;70:95–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abelson MB, Schaefer K. Conjunctivitis of allergic origin: immunologic mechanisms and current approaches to therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;38(Suppl):115–132. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(93)90036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abelson MB, Smith L, Chapin M. Ocular allergic disease: mechanisms, disease sub-types, treatment. Ocul Surf. 2003;1:127–149. doi: 10.1016/S1542-0124(12)70140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien TP. Allergic conjunctivitis: an update on diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13:543–549. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328364ec3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okuda M. Epidemiology of Japanese cedar pollinosis throughout Japan. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:288–296. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63532-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada T, Saito H, Fujieda S. Present state of Japanese cedar pollinosis: the national affliction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(632–9):e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uchio E. Treatment of allergic conjunctivitis with olopatadine hydrochloride eye drops. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2:525–531. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanier BQ, Finegold I, D’Arienzo P, Granet D, Epstein AB, Ledgerwood GL. Clinical efficacy of olopatadine vs epinastine ophthalmic solution in the conjunctival allergen challenge model. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:1227–1233. doi: 10.1185/030079904125004330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abelson MB, Greiner JV. Comparative efficacy of olopatadine 0.1% ophthalmic solution versus levocabastine 0.05% ophthalmic suspension using the conjunctival allergen challenge model. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:1953–1958. doi: 10.1185/030079904X5724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berdy GJ, Spangler DL, Bensch G, Berdy SS, Brusatti RC. A comparison of the relative efficacy and clinical performance of olopatadine hydrochloride 0.1% ophthalmic solution and ketotifen fumarate 0.025% ophthalmic solution in the conjunctival antigen challenge model. Clin Ther. 2000;22:826–833. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)80055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abelson MB, Chambers WA, Smith LM. Conjunctival allergen challenge. A clinical approach to studying allergic conjunctivitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:84–88. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070030090035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takamura E, Nomura K, Fujishima H, et al. Efficacy of levocabastine hydrochloride ophthalmic suspension in the conjunctival allergen challenge test in Japanese subjects with seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Allergol Int. 2006;55:157–165. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.55.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enomoto T, Lu HQ, Yin M, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of olopatadine and fexofenadine compared with placebo in Japanese cedar pollinosis using an environmental exposure unit. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2009;19:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bielory L, Ghafoor S. Histamine receptors and the conjunctiva. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:437–440. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000183113.63311.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto Y, Funahashi J, Mori K, Hayashi K, Yano H. The noncompetitive antagonism of histamine H1 receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells by olopatadine hydrochloride: its potency and molecular mechanism. Pharmacology. 2008;81:266–274. doi: 10.1159/000115970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsubara M, Tamura T, Ohmori K, Hasegawa K. Histamine H1 receptor antagonist blocks histamine-induced proinflammatory cytokine production through inhibition of Ca2+-dependent protein kinase C, Raf/MEK/ERK and IKK/I kappa B/NF-kappa B signal cascades. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:433–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yanni JM, Stephens DJ, Miller ST, et al. The in vitro and in vivo ocular pharmacology of olopatadine (AL-4943A), an effective anti-allergic/antihistaminic agent. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1996;12:389–400. doi: 10.1089/jop.1996.12.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanni JM, Weimer LK, Sharif NA, Xu SX, Gamache DA, Spellman JM. Inhibition of histamine-induced human conjunctival epithelial cell responses by ocular allergy drugs. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:643–647. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.