Abstract

Background

Left ventricular pacing (LVP) in canine heart alters ventricular activation leading to reduced transient outward potassium current, Ito, loss of the epicardial action potential notch, and T wave vector displacement (TVD). These repolarization changes, referred to as cardiac memory, are initiated by locally increased angiotensin II (AngII) levels. In HEK293 cells in which Kv4.3 and KChIP2, the channel subunits contributing to Ito, are overexpressed with the AngII receptor 1 (AT1R), AngII induces a decrease in Ito as the result of internalization of a Kv4.3/KChIP2/AT1R macromolecular complex.

Objective

We tested the hypothesis that in canine heart in situ, 2h LVP-induced decreases in membrane KChIP2, AT1R and Ito are prevented by blocking subunit trafficking.

Methods

We used standard electrophysiologic, biophysical and biochemical methods to study 4 groups of dogs: 1) Sham, 2) 2h LVP, 3) LVP+colchicine (microtubule disrupting agent) and 4) LVP+losartan (AT1R blocker).

Results

TVD was significantly greater in LVP than Shams and was inhibited by colchicine or losartan. Epicardial biopsies showed significant decreases in membrane KChIP2 and AT1R protein after LVP but not after sham treatment, and these decreases were prevented by colchicine or losartan. Colchicine but not losartan significantly reduced microtubular polymerization. In isolated ventricular myocytes AngII-induced Ito reduction and loss of action potential notch were blocked by colchicine.

Conclusions

LVP-induced reduction of KChIP2 in plasma light membranes depends on an AngII-mediated pathway and intact microtubular status. Loss of Ito and the action potential notch appear to derive from AngII-initiated trafficking of channel subunits.

Keywords: Ventricular pacing, Angiotensin II, Angiotensin receptor, Ion channel, Microtubule

1. Introduction

Ventricular pacing-induced T wave vector displacement is a manifestation of cardiac memory and results from the altered myocardial stretch that is produced by altered ventricular activation.1 We have shown that the T wave vector displacement induced by 20 min – 2 hours of left ventricular pacing is prevented by agents which block the transient outward current, Ito,2 the angiotensin II receptor 1 (AT1R)3, 4 or the L-type Ca channel.5 Whereas long term pacing (which results in long-term cardiac memory) induces changes in gene transcription for the pore-forming and accessory subunits of the channel determining Ito, 4, 6 the mechanism for the T wave vector displacement following short-term pacing (and seen as short-term memory) has been more elusive.7 Recently Doronin et al demonstrated that the Kv4.3/KChIP2 channel subunits responsible for Ito form a macromolecular complex with the AT1R.8 When transfected into a cell line, this complex produces a typical Ito, which decreases to near 0 following angiotensin II addition to the superfusate.8 This results from internalization of the macromolecular complex following angiotensin II binding to the AT1R, and suggests that internalization of the channel complex explains the loss of Ito8 These observations have been validated in single ventricular myocytes.8

Microtubules are a major component of the cardiac myocyte cytoskeleton, and play a central role in the trafficking of channel subunits to and from the plasma membrane.9, 10 Microtubular network disruption induced by treating cells with depolymerizing agents decreases internalization and increases cell surface expression of channel subunits.11–13 The result is increased outward potassium current and/or shortened action potential duration in rat ventricular myocytes and/or in cells stably expressing Kv1.5, Kv4.2, Kv2.1 or Kv3.1. Microtubules also are critical to membrane receptor regulation in cardiac myocytes. For example, G protein-coupled receptor desensitization resulting from agonist binding-induced receptor internalization is inhibited by disrupting the microtubular network.14, 15

Whether microtubular-mediated trafficking is responsible for the changes in repolarization that occur soon after onset of ventricular pacing in situ has been hypothesized7 but not tested. Therefore, we used a 2-hour pacing protocol that induces cardiac memory16 to test the hypothesis that left ventricular pacing-induced decreases in KChIP2 and AT1R protein in plasma membranes of the intact canine heart are prevented by the microtubule disrupting agent, colchicine. Sham instrumented animals and those treated with the AT1R blocker, losartan, provided control groups. Because we previously have shown in both a cell line and in cardiac myocytes that KChIP2 and Kv4.3 form a macromolecular complex with the AT1R in the setting of angiotensin II treatment,8 in the present studies we considered only the receptor and KChIP2. Concurrent studies in isolated canine ventricular myocytes were performed to determine whether the pharmacological intervention does in fact impact on Ito and the transmembrane action potential.

2. Methods

Experiments were performed using protocols approved by Columbia University’s and Stony Brook University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees and conform to the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication NO. 85-23, revised 1996). All the chemicals, except those specified, are from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA.

2.1 Pacing Protocol

The pacing protocol was modified after one previously described.16 In brief, 2–3 year old adult male mongrel dogs weighing 22–25 kg (Chestnut Grove Kennels, Shippensburg, PA, USA) were anesthetized using propofol (10 mg/kg IV, APP Pharmaceuticals Inc., Schaumburg, IL, USA), intubated, and ventilated with isoflurane (2%, Baxter International, Deerfield, IL, USA). Depth of anesthesia was monitored by a veterinary anesthesia technician throughout all surgical procedures. Systemic arterial blood pressure and a body surface electrocardiogram were continuously monitored intra-operatively. Increases in heart rate and blood pressure greater than 20% of initial values were used to indicate the need for increases in isoflurane levels. In addition, palpebral or corneal reflexes were monitored. Using sterile technique a left thoracotomy was performed and the heart was suspended in a pericardial cradle. Epicardial bipolar pacing electrodes were sewn to the left atrium, and the anterior wall or posterior left ventricular wall.

Figure 1 shows the experimental protocol. The sham group was atrially paced throughout the experiment (n=9). The other groups were left ventricular pacing (anterior wall, n=7; posterior wall, n=5), left ventricular pacing + colchicine (anterior wall, n=5; posterior wall, n=9) and left ventricular pacing + losartan (anterior wall, n=2; posterior wall, n=6). Colchicine was infused as a 1 mg/Kg IV bolus 30 min before left ventricular pacing and infused at 16μg/kg/min throughout left ventricular pacing. For AT1R blockade, losartan was injected as a 1 mg/Kg IV bolus 30 min before left ventricular pacing and infused at 30 μg/kg/min throughout the remaining protocol. At the start and end of each protocol an epicardial biopsy, 6 mm in diameter and 2 mm deep was taken 1–2 cm away from the left ventricular pacing electrode and quick frozen in liquid nitrogen for biochemical analysis. Switching the pacing site did not have any influence on the outcome of our biochemical studies. Due to the small size of the biopsies, there was insufficient material in any one biopsy to permit all the biochemical studies to be conducted on each sample. Thus, correlations that relate biochemical results with T wave vector displacement include only the electrophysiological results obtained from the dogs that actually provided samples for the appropriate biochemical measurement.

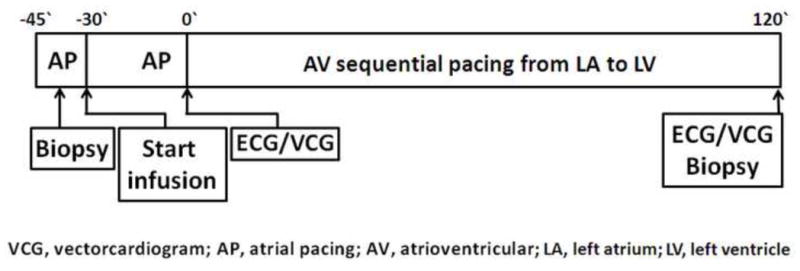

Figure 1.

Pacing and drug administration protocol. Atrial pacing was performed for 45 min. During the first 15 min, a reference biopsy was taken 1–2 cm away from the LV electrode. For dogs receiving drugs, colchicine or losartan bolus and infusion were started 30 min before LV pacing began and continued throughout the experiment. ECG and VCG were recorded at the times indicated. At the end of 2 h of pacing, another biopsy was taken 1–2 cm from the LV pacing electrode.

2.2 Preparation of whole cell lysates and extraction of light membrane fractions from biopsies

Whole cell lysates of cardiac biopsies were prepared with a lysate buffer containing 1x phosphate buffer saline, 1% triton X-100, 0.5% NaDoc, 0.1% Tween-20 and protease inhibitors (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). After biopsies were sonicated on ice they were rotated for 15 min at 4°C, and then centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm. The supernatants were used as whole cell lysates.

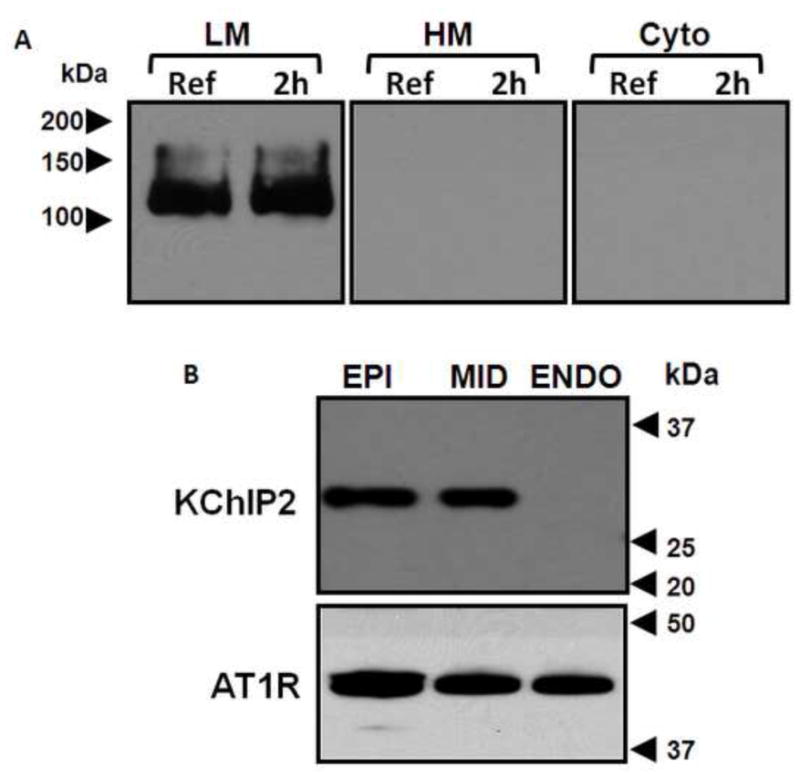

Preparation of light membrane fractions was modified from previous descriptions.17 Biopsies were rinsed with cold MT buffer (pH 7.4, 10 mM of Tris-MOPS, 1 mM EGTA, 250 mM sucrose and various protease inhibitors) and subjected to 20 strokes in a glass Dounce homogenizer (10 strokes with loose pestle and 10 strokes with tight pestle, Wheaton, Millville, NJ, USA). Debris which mainly includes connective tissue and non-broken cells was removed by a centrifugation at 2900 rpm for 5 min. The heavy membrane fraction, mainly including organelles, was removed by 10 min centrifugation at 9300 rpm. After additional high speed centrifugation at 53000 rpm for 1h, the pellet was used as the light membrane fraction and the supernatant was considered as the cytosolic fraction. To confirm the quality of the light membrane fractions, all fractions were subjected to Western blot for anti-adenylyl cyclase 6 antibody, which is used as a membrane marker (Figure 2A).18 We confirmed the specificity of the KChIP2 and AT1R antibodies by Western blot using whole cell lysates of left ventricular free wall epicardium, midmyocardium and endocardium. Consistent with the literature,19 KChIP2 protein was highly expressed in epicardium and midmyocardium and absent from endocardium. In contrast, AT1R protein (Figure 2B) and message (Supplementary Figure 1) were equivalent transmurally. Because prior research has shown the most prominent left ventricular pacing-induced changes in KChIP2 occur in epicardium,6 we focused on epicardial tissues in this study.

Figure 2.

Panel A: Light membrane fraction (LM), heavy membrane fraction (HM) and cytosolic fraction (Cyto) of biopsies taken before (Ref) and after 2 h of left ventricular pacing (2h) were Western blotted for adenylyl cyclase 6 (AC6) antibody. Note the presence of AC6 signal in the LM fraction but not in the HM or cytosolic fractions. Panel B: Whole cell lysates of epicardial (EPI), midmyocardial (MID) and endocardial (ENDO) tissues from control canine left ventricular free wall, Western blotted for KChIP2 and angiotensin II receptor 1 (AT1R) antibodies. KChIP2 is highly expressed in EPI and MID and absent from ENDO, whereas AT1R is equally expressed throughout the left ventricular free wall.

2.3 Extraction of total, non-polymerized and polymerized β-tubulin fractions from biopsies

Beta-tubulin fractions were extracted from biopsies using a method modified from Putnam et al.20 Briefly, biopsies were washed in microtubule stabilization buffer (MTSB, 0.1 M piperazine-N,N′-bis (2-ethanesulfonic acid) (Pipes, pH 6.75), 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgSO4, 2M glycerol, and protease inhibitor tablet (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) minced in Kontes Duall tissue grinder glass containing 1 ml of MTSB with 50 strokes (Kimble Kontes, Rochester, NY, USA). The lysates were centrifuged at 2900 rpm for 5 min to remove connective tissue and unbroken cells. The supernatant was centrifuged at 63,000 rpm for 45 min at room temperature and the supernatant was used as the non-polymerized tubulin fraction. After sonication in lysate buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.4 M NaCI, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate and protease inhibit tablets) for 30 sec the pellet were incubated on ice for 30 min and used as polymerized tubulin fraction.

2.4 Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously21 using anti-KChIP2 (UC Davis/NIH NeuroMab Facility, Davis, CA, USA), anti-AT1R (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-adenylate cyclase 6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and anti-β-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich St. Louis, MO, USA.) antibodies. Each image in each figure represents at least 4 independent experiments.

2.5 Patch clamp recording of calcium-insensitive transient outward potassium current

Myocytes were isolated from canine ventricular epicardium as previously described22 and incubated with AngII (2 uM) in the presence or absence of colchicine (150 uM) for 2 hours at room temperature and then stored at 4°C in angiotensin II or angiotensin II + colchicine prior to use (5–8 hours). Using a previously described patch clamp protocol21 cells were held at −65 mV, then briefly depolarized (5 ms) to −30 mV to inactivate INa and then depolarized to voltages from −30 to +50 mV for 300–500 ms. Currents were normalized to cell capacitance.

To record action potentials in these myocytes, the pipette solution contained 115 mM potassium aspartate, 35 mM KOH, 3 mM MgCl2, 3 mM MgATP, 10 mM HEPES, 11 mM EGTA and 5 mM glucose. The pH of the pipette solution was adjusted to 7.4 with KOH. The external solution contained 3 mM KCl, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES and 10 mM glucose. The pH of the external solution was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± S.E.M. Comparisons among group means were made by one way ANOVA. p<0.05 was considered significant.

3.1 Results

The T wave vector displacement induced by left ventricular pacing was significantly reduced by colchicine or losartan

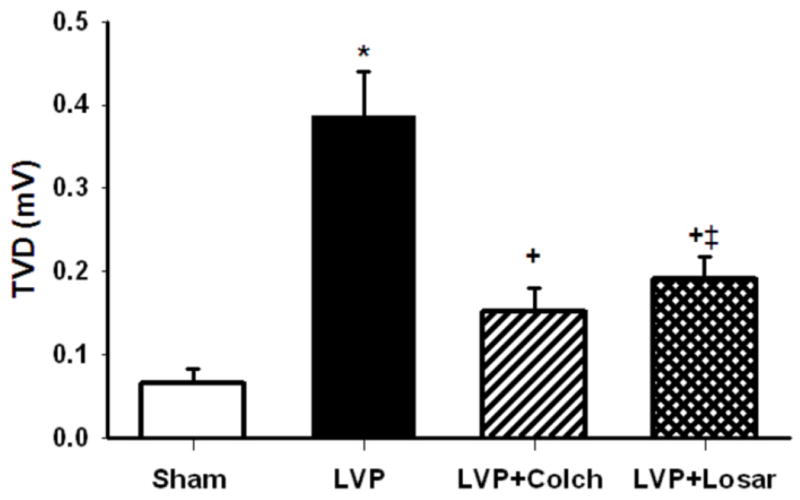

The T wave vector displacement, at the end of 2 hours pacing, was significantly higher in the left ventricular paced group than the sham group (Figure 3). In the colchicine and losartan groups the magnitude of the left ventricular pacing-induced T wave vector displacement was significantly reduced (Figure 3). Infusion of colchicine in the absence of ventricular pacing did not affect the T wave vector (0.091+/−0.027 mV for control group (n=6) and 0.088+/−0.033 mV for colchicine (n=3), p>0.05). We previously have reported there is no effect of AT1 receptor blockade or ACE inhibition on the T wave vector in the absence of ventricular pacing.3

Figure 3.

Summary data of T wave vector displacement (TVD). The TVD is significantly higher following 2h left ventricular pacing (LVP, n=5) compared to Sham (n=9, p<0.05). Colchicine (LVP + Colch, n=9) or losartan (LVP + Losar, n=6) infusion significantly reduced TVD compared to LVP (p<0.05). Because of the variability in T wave vector changes with left ventricular anterior and posterior wall pacing, we include here the analysis of posterior wall pacing only. *, P<0.05 vs Sham; +, P<0.05 vs LVP; ‡, P<0.05 vs Sham.

3.2 Left ventricular pacing resulted in loss of KChIP2 and AT1R from canine ventricular membrane fractions. This was blocked by colchicine or losartan

We previously showed that 3 weeks of ventricular pacing induced a significant decrease in the total expression level of KChIP2 in canine ventricular epicardium whole cell lysates.6 In contrast, 2 hours left of ventricular pacing induced no changes in total protein levels or mRNA levels of KChIP2 and AT1R (Figure 4A). This indicates that total KChIP2 and AT1R expression in the cell are constant at 2 hours. However, as shown in Figure 4B and C, KChIP2 and AT1R protein in the light membrane fraction were significantly decreased by left ventricular pacing but not by sham treatment, and these decreases were prevented by colchicine or losartan (p<0.05). To summarize, the total KChIP2 and AT1R protein in the cell (whole cell lysate) remain unchanged during pacing; both subunits are lost from the cell membrane during pacing; and this loss is prevented by colchicine or losartan.

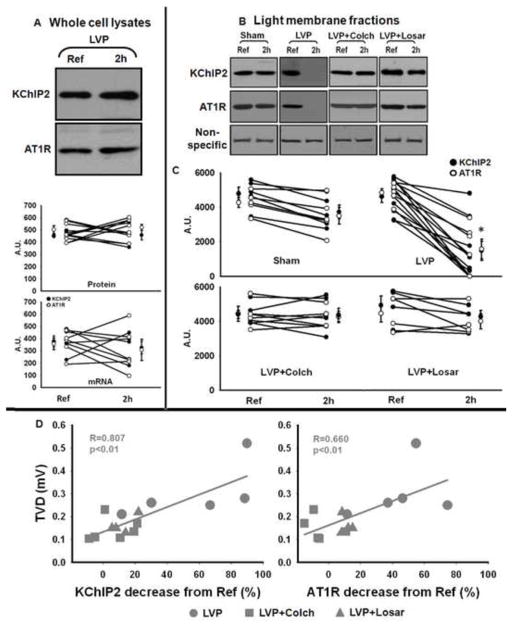

Figure 4.

Panel A (top): Representative Western blot images showing whole cell lysate expression of KChIP2 and AT1R in reference (Ref) and 2 hours of left ventricular pacing (LVP, 2h) biopsies. Panel A (bottom): Summary data of KChIP2 and AT1R protein level in whole cell lysate (n=6) and mRNA level (n=5). There are no significant changes in protein level or mRNA level after 2 hours of LVP.

Panel B: Representative Western blots of KChIP2 and AT1R in light membrane fractions. A non-specific band (around 80 kDa) from AT1R Western blot was used as a loading control. Panel C: Summary data for all experiments on light membranes (Sham, n=5; LVP, n=9 for KChIP2 and n=6 for AT1R; LVP + Colch, n=6 for KChIP2 and n=4 for AT1R; LVP + Losar, n=4; *, p<0.05 vs Ref).

Panel D: Correlation between the decrease in KChIP2 or AT1R in light membrane fractions and T wave vector displacement (TVD). Because in sham animals the T vector varied by up to 0.15 mV, we excluded all LVP animals that had a T vector displacement of less than 0.15 mV from the analysis in Panel D.

We also found a significant correlation between the reduction in KChIP2 or AT1R in the light membrane fractions and the increase in T wave vector displacement (Figure 4D). These data strongly suggest that left ventricular pacing-induced loss of the Ito channel constituents by trafficking from plasma membrane in vivo plays a significant role in the left ventricular pacing-induced changes in T wave vector displacement.

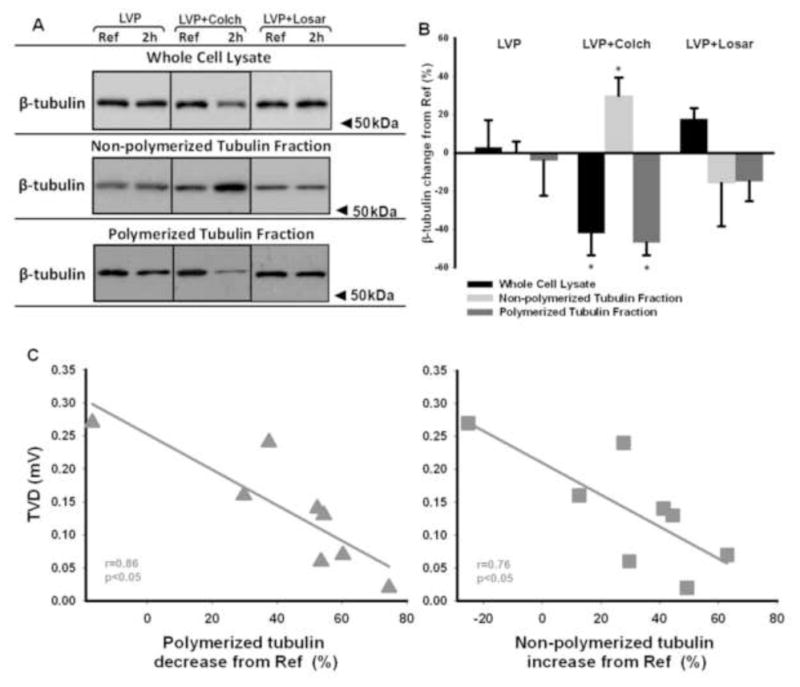

3.3 Colchicine but not losartan significantly reduces microtubular polymerization

To investigate the mechanism of the colchicine effect on left ventricular pacing-induced T wave vector displacement, we studied microtubule dynamics in the biopsies. The microtubular disrupting effect of colchicine in canine cardiomyocytes has been previously shown by others using immunofluorescence confocal microscopy23, 24. We employed β-tubulin fractionation and Western blot technique to determine the β-tubulin level in each fraction in each group. Figure 5A and B shows that with left ventricular pacing alone (left) or left ventricular pacing + losartan (right) there were no significant changes in total, non-polymerized or polymerized β-tubulin levels. In contrast, with left ventricular pacing + colchicine (center), the total and polymerized β-tubulin were significantly decreased and non-polymerized β-tubulin was significantly increased. Figure 5C shows that the dogs with the greatest reduction in polymerized tubulin and greatest increase in non-polymerized tubulin had the least T wave vector displacement. In contrast, the dogs with the least changes in polymerized and non-polymerized tubulin had the greatest T wave vector displacement. These results suggest that an intact microtubular network is critical for the left ventricular pacing-induced internalization of channel subunits and the induction of T wave vector displacement.

Figure 5.

Panel A: Whole cell lysate, non-polymerized and polymerized tubulin fractions of biopsies taken before (Ref) and after pacing (2h) were Western blotted for β-tubulin antibody. LVP, left ventricular pacing; Colch, colchicine; Losar, losartan. Panel B: Summary data for all experiments (*, p<0.05 vs LVP; LVP, n=5; LVP+Colch, n=8; LVP+Losar, n=4).

Panel C: In the presence of colchicine (n=8; why aren’t all 9 animals included? Because the tubulin fractionation was done only for 8 animals), the magnitude of T wave vector displacement (TVD) is strongly correlated to the decrease in polymerized tubulin and the increase in non-polymerized tubulin.

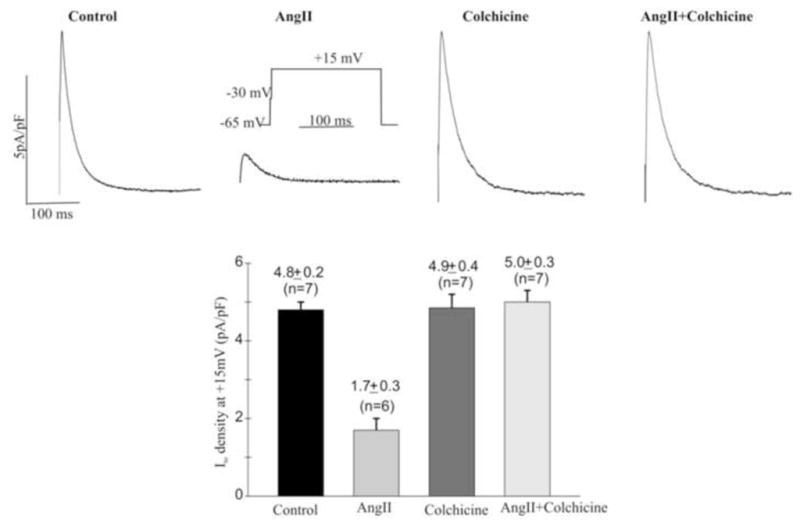

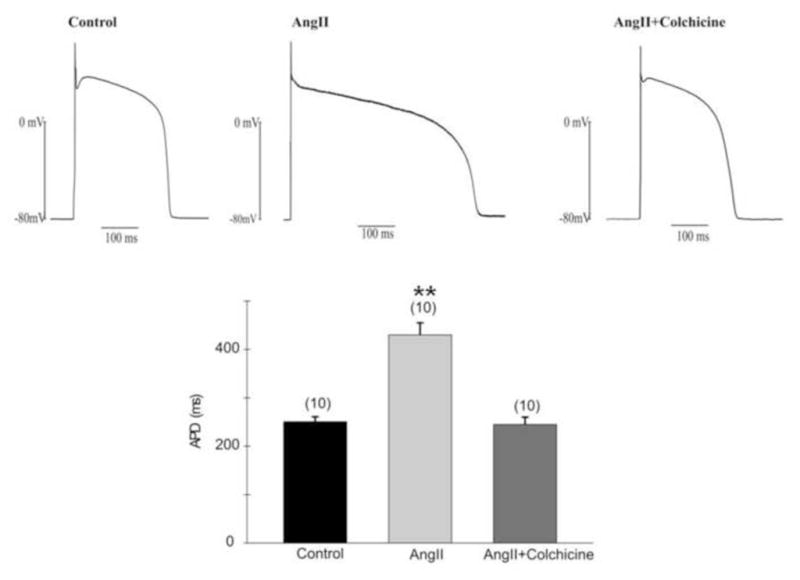

3.4 Colchicine reverses angiotensin II-induced reduction of Ito in isolated canine LV epicardial myocytes

We previously showed that 2 hours of left ventricular pacing significantly increase angiotensin II content in canine myocardium16 and that treating isolated canine ventricular epicardial myocytes with angiotensin II reduces Ito.22 The patch clamp experiments in Figure 6 confirm that angiotensin II reduces Ito. Importantly, Figure 6 also shows that colchicine alone has no effect on Ito, but it completely prevents the effect of angiotensin II to reduce the current. This outcome suggests that following microtubular disruption angiotensin II cannot internalize the Ito channel constituents, and the result is maintenance of the current. The impact of this on the action potential is shown in figure 7. As demonstrated by us previously 22 angiotensin II significantly reduces the phase 1 notch and prolongs action potential duration. Note that the effects on the notch and on duration are prevented by colchicine.

Figure 6.

Colchicine reverses the reduction of Ito induced by angiotensin II (AngII) in isolated canine ventricular myocytes. Top: Experimental traces of Ito in cardiomyocytes isolated from ventricular epicardium in the absence (Control) or presence of 2 uM angiotensin II (AngII), 150 uM colchicine, or AngII + colchicine (Colch). Bottom: Summary of Ito density in the conditions indicated. (**, P<0.01 vs Control, ANOVA).

Figure 7.

Colchicine reverses the action of angiotensin II to reduce the subepicardial action potential (AP) notch and prolong repolarization. Top: Representative AP in Control (left panel), Ang II (2uM, Middle panel) and Ang II with Colchicine (150uM, right panel), respectively. Cells were injected with a 180pA current for 10ms. APs were recorded under steady state conditions in current clamp. Bottom: Averaged AP durations in angiotensin II with or without colchicine. Note a significantly prolonged APD in the presence of angiotensin II which was reversed in the presence of angiotensin II and colchicine (P<01 vs. Control, ANOVA). A comparable result was seen for the phase 1 notch: this was 12.0 ±1.5mV in control, −11.1 ±1.4mV in angiotensin II plus colchicine and 5.5±1.1 mV in angiotensin II (P<01 vs. Control and angiotensin II + colchicine).

4. Discussion

The molecular mechanisms of ventricular pacing-induced cardiac memory have been studied extensively.1, 4–6, 16 Moreover, cardiac memory provides a useful framework for understanding the evolution of remodeling because the pacing used to induce memory initiates two different yet complimentary processes. While long-term cardiac memory is the result of transcriptional changes of ion channels and Cx43,4, 5, 25, 26 short-term memory has been proposed to result from ion channel trafficking initiated by altered myocardial stretch-induced synthesis and release of angiotensin II.7,8 In this study, we demonstrated in intact animals that the internalization of Ito channel subunits initiated by the binding of angiotensin II to the AT1R previously shown in single cell studies contributes to the induction of short-term cardiac memory and this internalization process uses a microtubule-mediated pathway.

Surface expression of ion channels is regulated by many factors including gene expression, post translational modification, and channel trafficking and insertion into the plasma membrane.9 Channels expressed at the cell surface are regularly internalized for recycling or degradation. Interference with recycling and degradation can alter the expression of functional ion channels in plasma membranes, and thereby, alter the electrical activity of cardiomyocytes.

We previously reported that Ito is critically involved in the induction of cardiac memory,2, 4, 6, 27, 28 and now have studied the molecular mechanism for rapid change following 2 hours of ventricular pacing. In this study, pacing did not alter the total protein level of KChIP2 or the AT1R in whole cell lysates (Figure 4A). Moreover, there is no change in mRNA for KChIP2 or the AT1R (Figure 4A). This excludes the occurrence of pacing-induced transcriptional remodeling contributing to the physiological outcomes at 2 hour. However, the KChIP2 and AT1R protein in the membrane fraction are significantly decreased after left ventricular pacing (Figure 4B and C), and the loss of protein from the membrane correlates with the magnitude of the T wave vector displacement change. That is, those dogs having greater decreases in KChIP2 and AT1R had greater T wave vector displacements (Figure 4D). In addition, the AT1R blocker, losartan, not only inhibited the induction of T wave vector displacement but it also prevented the loss of KChIP2 and AT1R from the membrane fractions. Together these findings strongly support our hypothesis that left ventricular pacing-induced T wave vector displacement is at least in part the result of the reduction of KChIP2 in plasma membranes through an internalization process which is mediated by an angiotensin II-AT1R-pathway.

There are multiple routes via which ion channels might be internalized and eventually recycled or degraded.29 In this study, disruption of the microtubular network by colchicine not only inhibited pacing-induced T wave vector displacement (Figure 3), it also prevented the loss of KChIP2 and AT1R from the membrane fraction (Figures 4B and C), and prevented the effect of angiotensin II to reduce Ito or the action potential notch (Figures 6,7). This suggests the microtubular network is important to the pacing-induced ion channel internalization. Although losartan inhibited the induction of T wave vector displacement and also prevented the loss of KChIP2 and AT1R from the membrane fraction, it did not affect microtubular dynamics. These results suggest that colchicine and losartan inhibit pacing-induced T wave vector displacement by completely different mechanisms: colchicine disrupts the microtubular network, thereby preventing internalization of the Kv4.3/KChIP2/AT1R macromolecular complex, while losartan inhibits the action of angiotensin II by blocking the AT1R. This is consistent with our previous in vitro experiments in which a stable Kv4.3/KChIP2/AT1R macromolecular complex in a cell line or myocyte delivers a robust Ito and angiotensin II binding to the AT1R in the macromolecular complex is essential for its internalization.8

The results in Figure 5A and B show that exposure to colchicine not only disrupted the microtubular network, but it induced a significant decrease in the total β-tubulin protein level. This finding is consistent with studies showing that in mammalian cells the production of tubulin mRNA is controlled by the concentration of non-polymerized tubulin, via autoregulation of tubulin synthesis.30, 31 Disruption of microtubules by colchicine and the concomitant increase in non-polymerized tubulin concentrations result in cessation of tubulin mRNA production. Tubulin mRNA has a half-life of only 2 hours and colchicine-induced microtubulin disruption has been shown to result in a decrease in total tubulin protein levels,30 a phenomenon we observed as well in our study.

In conclusion, our results suggest that left ventricular pacing-induced reduction of KChIP2 in plasma membranes depends on an angiotensin II-AT1R-mediated pathway and intact microtubular status. By implication, loss of Ito and the action potential notch in heart in situ appear to derive from angiotensin II -AT1R-induced trafficking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [HL67101]. Gerard Boink received grant support from the Netherlands Heart Foundation; the Netherlands Foundation for Cardiovascular Excellence; the Dr. Saal van Zwanenberg foundation; and the Interuniversity Cardiology Institute of the Netherlands.

We thank Joan Zuckerman for her technical assistance with canine cardiac myocytes dissociation.

Glossary of abbreviations

- AT1R

angiotensin II receptor 1

- KChIP2

K+ channel interacting protein 2

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sosunov EA, Anyukhovsky EP, Rosen MR. Altered ventricular stretch contributes to initiation of cardiac memory. Heart Rhythm. 2008 Jan;5:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.del Balzo U, Rosen MR. T wave changes persisting after ventricular pacing in canine heart are altered by 4-aminopyridine but not by lidocaine. Implications with respect to phenomenon of cardiac ‘memory’. Circulation. 1992 Apr;85:1464–1472. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.4.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ricard P, Danilo P, Jr, Cohen IS, Burkhoff D, Rosen MR. A role for the renin-angiotensin system in the evolution of cardiac memory. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999 Apr;10:545–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patberg KW, Plotnikov AN, Quamina A, et al. Cardiac memory is associated with decreased levels of the transcriptional factor CREB modulated by angiotensin II and calcium. Circ Res. 2003 Sep 5;93:472–478. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000088785.24381.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plotnikov AN, Yu H, Geller JC, et al. Role of L-type calcium channels in pacing-induced short-term and long-term cardiac memory in canine heart. Circulation. 2003 Jun 10;107:2844–2849. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000068376.88600.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patberg KW, Obreztchikova MN, Giardina SF, et al. The cAMP response element binding protein modulates expression of the transient outward current: implications for cardiac memory. Cardiovasc Res. 2005 Nov 1;68:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozgen N, Rosen MR. Cardiac memory: a work in progress. Heart Rhythm. 2009 Apr;6:564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doronin SV, Potapova IA, Lu Z, Cohen IS. Angiotensin receptor type 1 forms a complex with the transient outward potassium channel Kv4. 3 and regulates its gating properties and intracellular localization. J Biol Chem. 2004 Nov 12;279:48231–48237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steele DF, Zadeh AD, Loewen ME, Fedida D. Localization and trafficking of cardiac voltage-gated potassium channels. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007 Nov;35:1069–1073. doi: 10.1042/BST0351069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caviston JP, Holzbaur EL. Microtubule motors at the intersection of trafficking and transport. Trends Cell Biol. 2006 Oct;16:530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loewen ME, Wang Z, Eldstrom J, et al. Shared requirement for dynein function and intact microtubule cytoskeleton for normal surface expression of cardiac potassium channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009 Jan;296:H71–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00260.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi WS, Khurana A, Mathur R, Viswanathan V, Steele DF, Fedida D. Kv1. 5 surface expression is modulated by retrograde trafficking of newly endocytosed channels by the dynein motor. Circ Res. 2005 Aug 19;97:363–371. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000179535.06458.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White E. Mechanical modulation of cardiac microtubules. Pflugers Arch. Jul;462:177–184. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0963-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Limas CJ, Limas C. Involvement of microtubules in the isoproterenol-induced ‘down’-regulation of myocardial beta-adrenergic receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983 Oct 26;735:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(83)90273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marsh JD, Lachance D, Kim D. Mechanisms of beta-adrenergic receptor regulation in cultured chick heart cells. Role of cytoskeleton function and protein synthesis. Circ Res. 1985 Jul;57:171–181. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozgen N, Lau DH, Shlapakova IN, et al. Determinants of CREB degradation and KChIP2 gene transcription in cardiac memory. Heart Rhythm. 2010 Jul;7:964–970. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ventura A, Maccarana M, Raker VA, Pelicci PG. A cryptic targeting signal induces isoform-specific localization of p46Shc to mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004 Jan 16;279:2299–2306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao T, Puri TS, Gerhardstein BL, Chien AJ, Green RD, Hosey MM. Identification and subcellular localization of the subunits of L-type calcium channels and adenylyl cyclase in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997 Aug 1;272:19401–19407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosati B, Pan Z, Lypen S, et al. Regulation of KChIP2 potassium channel beta subunit gene expression underlies the gradient of transient outward current in canine and human ventricle. J Physiol. 2001 May 15;533:119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0119b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Putnam AJ, Cunningham JJ, Dennis RG, Linderman JJ, Mooney DJ. Microtubule assembly is regulated by externally applied strain in cultured smooth muscle cells. J Cell Sci. 1998 Nov;111 (Pt 22):3379–3387. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.22.3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozgen N, Guo J, Gertsberg Z, Danilo P, Jr, Rosen MR, Steinberg SF. Reactive oxygen species decrease cAMP response element binding protein expression in cardiomyocytes via a protein kinase D1-dependent mechanism that does not require Ser133 phosphorylation. Mol Pharmacol. 2009 Oct;76:896–902. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.056473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu H, Gao J, Wang H, et al. Effects of the renin-angiotensin system on the current I(to) in epicardial and endocardial ventricular myocytes from the canine heart. Circ Res. 2000 May 26;86:1062–1068. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.10.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koide M, Hamawaki M, Narishige T, et al. Microtubule depolymerization normalizes in vivo myocardial contractile function in dogs with pressure-overload left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 2000 Aug 29;102:1045–1052. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsutsui H, Tagawa H, Kent RL, et al. Role of microtubules in contractile dysfunction of hypertrophied cardiocytes. Circulation. 1994 Jul;90:533–555. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obreztchikova MN, Patberg KW, Plotnikov AN, et al. I(Kr) contributes to the altered ventricular repolarization that determines long-term cardiac memory. Cardiovasc Res. 2006 Jul 1;71:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel PM, Plotnikov A, Kanagaratnam P, et al. Altering ventricular activation remodels gap junction distribution in canine heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001 May;12:570–577. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geller JC, Rosen MR. Persistent T-wave changes after alteration of the ventricular activation sequence. New insights into cellular mechanisms of ‘cardiac memory’. Circulation. 1993 Oct;88:1811–1819. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plotnikov AN, Sosunov EA, Patberg KW, et al. Cardiac memory evolves with age in association with development of the transient outward current. Circulation. 2004 Aug 3;110:489–495. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000137823.64947.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steele DF, Eldstrom J, Fedida D. Mechanisms of cardiac potassium channel trafficking. J Physiol. 2007 Jul 1;582:17–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.130245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ben-Ze’ev A, Farmer SR, Penman S. Mechanisms of regulating tubulin synthesis in cultured mammalian cells. Cell. 1979 Jun;17:319–325. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleveland DW, Lopata MA, Sherline P, Kirschner MW. Unpolymerized tubulin modulates the level of tubulin mRNAs. Cell. 1981 Aug;25:537–546. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.