Abstract

Heparanase activity plays a decisive role in cell dissemination associated with cancer metastasis. Cellular uptake of heparanase is considered a pre-requisite for the delivery of latent 65-kDa heparanase to lysosomes and its subsequent proteolytic processing and activation into 8- and 50-kDa protein subunits by cathepsin L. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans, and particularly syndecan, are instrumental for heparanase uptake and activation, through a process that has been shown to occur independent of rafts. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism underlying syndecan-mediated internalization outside of rafts is unclear. Here, we examined the role of syndecan-1 cytoplasmic domain in heparanase processing, utilizing deletion constructs lacking the entire cytoplasmic domain (Delta), the conserved (C1 or C2), or variable (V) regions. Heparanase processing was markedly increased following syndecan-1 over-expression; in contrast, heparanase was retained at the cell membrane and its processing was impaired in cells over-expressing syndecan-1 deleted for the entire cytoplasmic tail. We have next revealed that conserved domain 2 (C2) and variable (V) regions of syndecan-1 cytoplasmic tail mediate heparanase processing. Furthermore, we found that syntenin, known to interact with syndecan C2 domain, and α actinin are essential for heparanase processing.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-014-1629-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Heparanase, Uptake, Syndecan, Cytoplasmic tail, Processing

Introduction

Heparanase is the only functional endoglycosidase capable of cleaving heparan sulfate (HS) in mammals, activity that is highly implicated in cell dissemination associated with tumor metastasis, inflammation, and angiogenesis [1–3]. Similar to several other classes of enzymes, heparanase is first synthesized as a latent enzyme that appears as a ~65-kDa protein when analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The 65-kDa latent enzyme is directed to the ER by a 35-amino-acid signal peptide, and is readily detected in the culture medium of transfected cells [4]. The secreted latent heparanase does not accumulate extracellularly, however, due to efficient cellular uptake. A number of studies have shown that exogenously added heparanase rapidly interacts with primary (i.e., fibroblasts, endothelial cells) and tumor-derived cells, followed by internalization and processing into a highly active enzyme [4–8], collectively defined as heparanase uptake. Several approaches, including HS-deficient cells, addition of heparin or xylosides, and deletion of HS-binding domains of heparanase, provided compelling evidence for the involvement of HS in heparanase uptake [4, 9]. Heparanase uptake is considered a pre-requisite for the delivery of latent 65-kDa heparanase to lysosomes and its subsequent proteolytic processing and activation into 8- and 50-kDa protein subunits by cathepsin L. This notion is supported by the following considerations. Following uptake, heparanase was noted to reside primarily intracellularly within endocytic vesicles, assuming a polar, peri-nuclear localization and co-localizing with lysosomal marker [4, 6, 10]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that incubation with endosomal/lysosomal, but not membrane or cytosolic preparations, leads to heparanase processing and activation [11]. Likewise, heparanase processing was blocked by chloroquine and bafilomycin A1, which inhibit lysosomal proteases by raising the lysosome pH [8]. Subsequent studies employing site-directed mutagenesis, gene silencing, and pharmacological inhibitors have identified cathepsin L as the primary lysosomal protease responsible for heparanase processing and activation [12–14].

Efficient uptake of heparanase was evident also by GPI-deficient cells (i.e., lacking cell surface glypicans) [4], suggesting preferential involvement of syndecans in this process. Notably, syndecan-1 and 4 are internalized by cells following addition of exogenous heparanase, co-localizing with heparanase in endocytic vesicles [4, 15, 16]. The molecular mechanism underlying internalization of the heparanase–syndecan complex, leading to heparanase processing and activation, is incompletely understood.

Internalization of syndecan ligands has been reported to occur via lipid rafts and clathrin-coated pits. For example, atherogenic lipoproteins enriched in lipoprotein lipase (LpL) are internalized via lipid rafts [17, 18], while the Wnt modulator R-Spondin (Rspo) 3 binds syndecan-4 and induces syndecan-4-dependent, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, leading to increased Wnt signaling [19]. Similarly, heparanase seems to utilize coated pits rather than lipid rafts as the primary endocytosis route. This emerged from sucrose gradient studies in which heparanase appeared to reside predominantly in non-raft fractions following exogenous addition [20]. Very small yet detectable levels of heparanase could be identified in raft fractions before but not after treatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin, associated with increased Akt phosphorylation in the raft microdomain [20]. In addition, the kinetics of heparanase uptake appeared very fast, and processing was evident already 15 min following addition of heparanase to mouse embryonic fibroblasts [6], in agreement with the rapid events associated with coated pit-mediated endocytosis [21] compared with t1/2 of 1 h for internalization via lipid rafts [16, 17]. Importantly, syndecan ligands internalized via rafts (i.e., lipoproteins) are subjected to total destruction into individual amino acids [17, 18]. In contrast, the activity of at least some syndecan ligands that get internalized via clathrin coated pits is preserved and even increased (i.e., heparanase processing, Rspo3 and Wnt signaling) [19, 22]. Recently, it has been reported that cortactin mediates raft-dependent endocytosis of syndecan-1 and of a FcR-syndecan-1 chimera in hepatoma cell line, involving a new membrane-proximal motif (MKKK) within the C1 domain of syndecan-1 [23]. Given the notion that heparanase gets internalized via clathrin-coated pits, we suspected that the mechanism undelaying heparanase internalization might differ from the one utilized to internalize syndecan-1 ligands by lipid rafts [23].

Here, we examined the role of syndecan-1 cytoplasmic domain in heparanase processing. To this end, we transfected cells with full-length mouse syndecan-1 or deletion constructs lacking the entire cytoplasmic domain (Delta), the conserved (C1 or C2), or variable (V) regions. Heparanase binding, internalization, and processing were then evaluated by immunofluorescent staining, immunoblotting, and activity assays. Heparanase uptake was markedly increased following syndecan-1 over-expression, thus challenging the notion that the HS coat saturates available space on the cell membrane and is not a limiting factor for ligand binding. In contrast, heparanase was retained at the cell membrane and its processing was impaired in cells over-expressing syndecan-1 deleted for the entire cytoplasmic tail. We have next revealed that conserved domain 2 (C2) and variable (V) regions of syndecan-1 cytoplasmic tail mediate heparanase processing. Furthermore, we found that syntenin, known to interact with syndecan C2 domain, and α actinin are essential for heparanase processing.

Materials and methods

Syndeacn-1 gene constructs

Mouse syndecan-1 cDNA was kindly provided by Dr. Ralph D. Sanderson (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL). The following oligonucleotides were used to delete the entire cytoplasmic tail (Delta), the conserved (C1, C2), or variable (V) domains by PCR:

Delta: 5′-GTG GAT CCA GGG CAT AGA ATT CCT CC (forward) and 5′-CAC TCG AGC CAC CAT GAG GCG CGC (reverse);

C1: 5′-CTT TCA TGC TGT ACC GGA TGT CCT TGG AGG AGC CCA AAC (forward) and 5′-GTT TGG GCT CCT CCA AGG ACA TCC GGT ACA GCA TGA AAG (reverse);

C2: 5′-CCC ACC AAG CAG GAG TGA TGG GGA AAT AG (forward) and 5′-CTA TTT CCC CAT CAC TCC TGC TTG GTG GG (reverse);

V: 5′-GAC GAA GGC AGC TAC GAG TTC TAC GCC TG (forward) and 5′-CAG GCG TAG AAC TCG TAG CTG CCT TCG TC (reverse).

Cells, cell culture, and cell sorting

HEK-293 human embryonic kidney, U87-MG human glioma, and MDA-MB-231 human breast carcinoma cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Cells were passed in culture no more that 2 months after being thawed from authentic stocks.

Antibodies and reagents

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies #1453 was prepared against purified latent 65-kDa heparanase [8]. Anti-heparanase monoclonal antibody was kindly provided by ImClone Systems (New York, NY, USA). Anti-heparanase-2 antibody (20C5) has been described [15]. Rat anti-mouse syndecan-1 monoclonal antibody (clone 281-2) was kindly provided by Dr. Ralph D. Sanderson (UAB). This antibody is directed against the ectodomain of mouse syndecan-1 and is suitable for flow cytometry, immune staining, and immunoblotting. Anti-vinculin and anti-actin monoclonal antibodies, phalloidin-TRITC, heparin, and methyl-β-cyclodextrin were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Anti-α-actinin, anti-cortactin, anti-Rab7, and anti-Rab9 antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA, USA). Anti-syntenin, anti-LAMP1, and anti-Myc Tag antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Latent 65-kDa heparanase was purified from medium conditioned by HEK-293 cells over-expressing heparanase essentially as described [24].

Cell lysates and immunoblotting

Cell extracts were prepared using a lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 % Triton X-100, supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche). Protein concentration was determined (Bradford reagent, Bio-Rad) and 30 µg of protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The membrane was probed with the appropriate antibody followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and a chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), as described [15].

Immunocytochemistry

For immunofluorescent staining, cells were fixed with cold methanol for 10 min, washed with PBS and subsequently incubated in PBS containing 10 % normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature, followed by 2-h incubation with the indicated primary antibody. Cells were then extensively washed with PBS and incubated with the relevant Cy2/Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h, washed and mounted (Vectashield, Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA). Staining was observed under a fluorescent confocal microscope. For actin staining, cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5 % Triton X-100 for 2 min, washed and incubated with TRITC-phalloidin (Sigma) for 30 min, and visualized by confocal microscopy, as described [25]. Images were visualized using confocal microscope (LSM 700) and Zen 2009 image-acquisition and analysis software (Carl Zeiss). The intensity and scattering of heparanase-positive endocytic vesicles staining was carried out using ZEN image processing software. Staining intensity was normalized to cell area.

Gene silencing and PCR analysis

Transfection and analysis of cells following siRNA transfection were carried out essentially as described [26]. Anti-syntenin, anti-α-actinin, anti-CASK, anti-Rab9, anti-cortactin, and control anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) siRNA oligonucleotides (siGENOME ON-TARGET plus SMART pool duplex) were purchased from Dharmacon (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) and transfection was carried out with DharmaFECT3 reagent according to the manufacturer’s (Dharmacon) instructions, as described [27]. Gene silencing was evaluated by immunoblotting as described above.

Heparanase activity assay

Preparation of Na352SO4-labeled ECM-coated 35-mm dishes and determination of heparanase activity were performed essentially as described in detail elsewhere [28]. Briefly, cells (2 × 106) were lysed by three cycles of freeze/thaw, and the resulting cell extracts were incubated (18 h, 37 °C) with 35S-labeled ECM. The incubation medium (1 ml) containing sulfate-labeled degradation fragments was subjected to gel filtration on a Sepharose CL-6B column. Fractions (0.2 ml) were eluted with PBS and their radioactivity was counted in a β-scintillation counter. Degradation fragments of HS side chains produced by heparanase are eluted at 0.5 < K av < 0.8 (peak II, fractions 12–22). Nearly intact HSPGs released from the ECM are eluted just after the V 0 (K av < 0.2, peak I, fractions 3–12) [28]. These high molecular weight products are released by proteases that cleave the HSPG core protein.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SE. Statistical significance was analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant. Data sets passed D’Agostino-Pearson normality (GraphPad Prism 5 utility software). All experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

Results

Heparanase uptake is mediated by syndecan-1 cytoplasmic domain

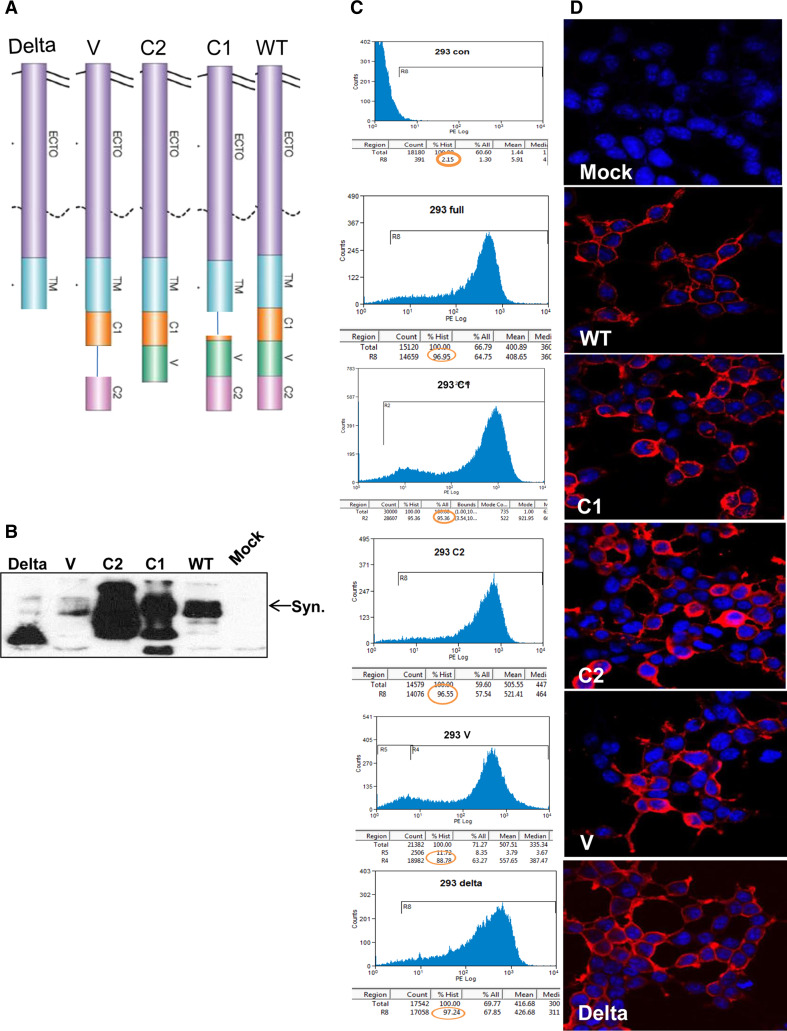

In order to appreciate the significance of syndecan-1 in heparanase uptake, we transfected 293 cells with wild-type (WT) mouse syndecan-1 or deletion constructs lacking the entire cytoplasmic domain (Delta), the conserved (C1, C2), or variable (V) regions (Fig. 1a). Since the expression levels of the syndecan-1 variants varied (Fig. 1b), cells were sorted to obtain homogenous populations of high-expressing cells. FACS analyses of the sorted cells revealed that all syndecan-1 variants are highly expressed by over 95 % of the cells (Fig. 1c), localizing at the cell surface (Fig. 1d), as expected. Similar transfection, sorting, and validation approaches were carried out with U87 glioma and MDA-231 breast carcinoma cells (not shown). In U87 glioma cells, over-expression of wild-type mouse syndecan-1 was associated with a twofold increase in focal adhesions evident by vinculin staining (Suppl. Fig. 1a, b; WT; p = 0.001), thus indicating the functionality of this molecule, in agreement with the role of syndecan-1 in cell adhesion [29, 30]. Over-expression of syndecan-1 lacking the entire cytoplasmic domain or the V region resulted in decreased vinculin staining (Suppl. Fig. 1a, b; Delta, V) (p = 0.05 and 0.01 for Mock vs. Delta and Mock vs. V region, respectively). Deletion of the C1 or C2 domains of syndecan-1 did not significantly alter the formation of focal contacts in U87 cells (Suppl. Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1.

Syndecan-1 gene constructs and expression. a Schematic diagram of syndecan-1 gene constructs utilized in this study. b–d Syndecan-1 expression. b 293 cells were stably transfected with the mouse syndecan-1 gene constructs and expression levels were evaluated by immunoblotting applying anti-mouse syndecan-1 monoclonal antibody. Cells were sorted to obtain homogenous cell populations exhibiting high levels of syndecan expression. Sorted cells were subjected to FACS analyses (c) and immunofluorescent staining (d) applying anti-mouse syndecan-1 monoclonal antibody. Note high expression of all syndecan-1 variants and their localization on the cell membrane

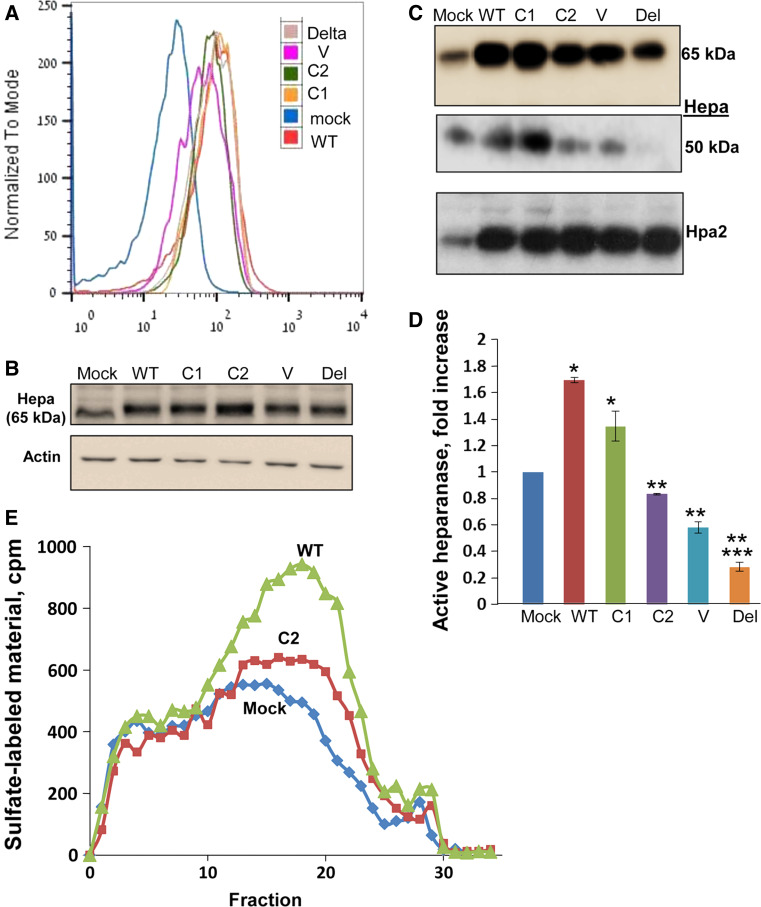

In order to examine the significance of the syndecan-1 variants in uptake, heparanase was added to cell cultures and binding, internalization, and processing were evaluated. We first examined the capacity of the syndecan variants to bind heparanase. To this end, heparanase was added to 293 cells expressing syndecan-1 variants for 1 h on ice, enabling binding but not internalization. FACS analysis indicated similar binding capacity of heparanase by all syndecan-1 variants that was increased compared with control mock transfected cells (Fig. 2a). Immunoblotting of corresponding cultures further confirmed that deleting the entire or selected domains of syndecan-1 cytoplasmic tail did not affect its capacity to bind heparanase (Fig. 2b). Similar experiments performed at 37 °C revealed, nonetheless, noticeable differences in heparanase binding, internalization, and processing. Over-expression of wild-type syndecan-1 resulted in a marked increase in binding of latent 65-kDa heparanase compared with control mock transfected cells (Fig. 2c, upper panel; WT). Accordingly, processing of latent heparanase and formation of the active 50-kDa subunit was increased nearly twofold in cells over-expressing wild-type syndecan-1 (Fig. 2c, middle panel; WT), increase that is statistically highly significant (Fig. 2d; p = 0.0009). In contrast, the levels of active (50-kDa) heparanase was markedly reduced in cells over-expressing syndecan-1 deleted of the entire cytoplasmic domain (Fig. 2c, del; Fig. 2d). In these cells, the level of active 50-kDa heparanase was threefold lower compared with control mock transfected cells (Fig. 2c, d; p = 0.0005), implying that heparanase processing requires intact syndecan-1 cytoplasmic tail. Moreover, heparanase processing was reduced to the level of control cells upon deletion of the variable (V) or conserved 2 (C2) domains, and exhibiting over twofold lower levels of 50-kDa active heparanase compared with cells over-expressing WT syndecan-1 or syndecan-1 lacking the conserved 1 (C1) domain (Fig. 2c; Fig. 2d; p = 0.001 and p = 0.0006 for WT/C1 vs. C2 and V, respectively), pointing to specific domains of syndecan-1 that mediate heparanase processing. Likewise, heparanase activity was increased in cells over-expressing wild-type syndecan-1 but not the C2 variant (Fig. 2e), further supporting a role for this region in heparanase activation. Binding of heparanase-2 (Hpa2), a close homolog of heparanase [31], was similarly increased substantially following syndecan-1 over-expression (Fig. 2c, lower panel, WT). Unlike heparanase, however, deletion of syndecan-1 cytoplasmic tail or specific domains did not affect Hpa2 binding at 37 °C (Fig. 2c, lower panel). This result implies that syndecan-1 cytoplasmic domain is required for the internalization of selected ligands, because Hpa2 binds HSPG (i.e., syndecans) with high affinity but does not get internalized [15].

Fig. 2.

Heparanase uptake. a Heparanase binding. Heparanase (1 μg/ml) was added to 293 cells over-expressing syndecan-1 variants for 1 h on ice. Cells were then washed twice with cold PBS and subjected to FACS analyses applying anti-Myc Tag antibody. Corresponding cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-heparanase (b, upper panel) and anti-actin (b, lower panel) antibodies. c, d Heparanase processing. Heparanase or heparanase-2 (1 μg/ml) were added to 293 cells over-expressing syndecan-1 variants for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and lysate samples were subjected to immunoblotting applying anti-heparanase (Hepa; upper and middle panels) and anti-heparanase-2 (Hpa2, lower panel) antibodies. The heparanase blot is shown at short (upper panel) and longer (middle panel) exposures depicting the latent (65-kDa) and processed (50-kDa) forms of heparanase. Densitometry quantification of the 50-kDa processed heparanase following uptake in five independent experiments is shown graphically in d. Note increased heparanase processing by cells over-expressing wild-type or C1 variant of syndecan, but reduced processing following over-expression of syndecan-1 deleted for the entire cytoplasmic tail (Del), the V region or C2 domain. *p = 0.0009 and 0.01 for Mock vs. WT and Mock vs. C1, respectively; **p = 0.001, 0.0006, and 0.0004 for WT vs. C2, WT vs. V, and WT vs. Delta, respectively; ***p = 0.0005 for Mock vs. Delta. e Heparanase enzymatic activity following heparanase addition to control (Mock) transfected cells, or cells over-expressing wild-type (WT) or the C2 variant of syndecan 1

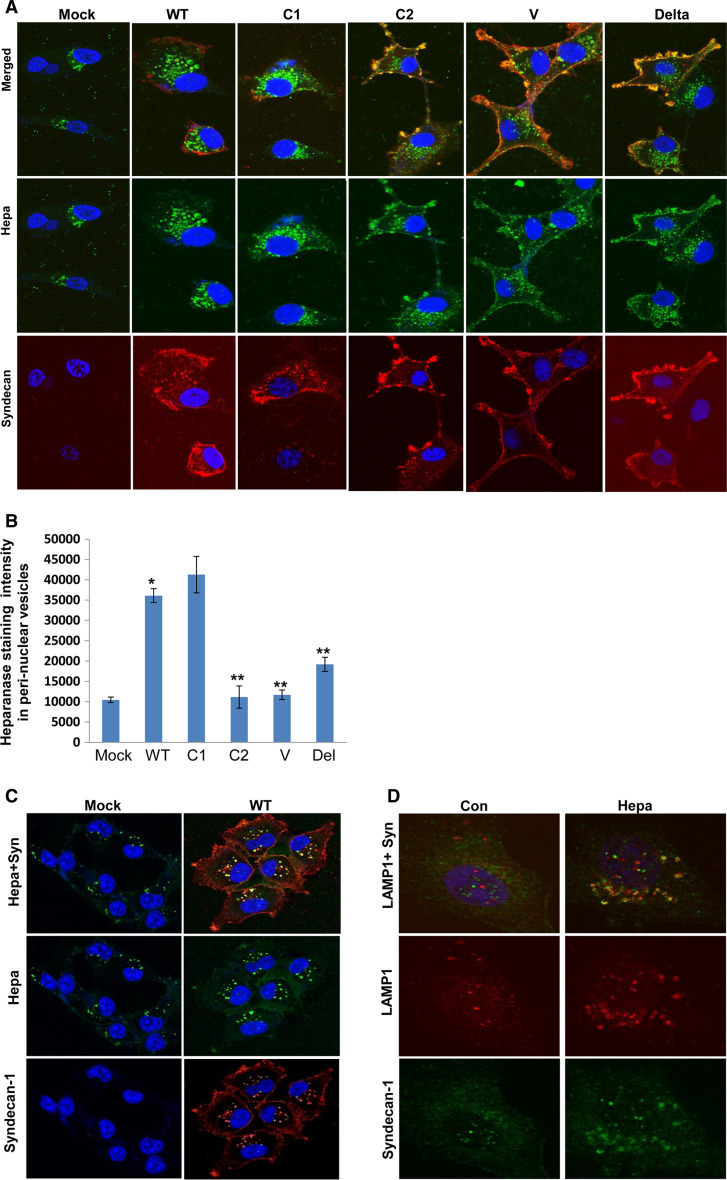

While processing of heparanase by cells lacking the entire cytoplasmic tail of syndecan-1 decreased below the levels of control mock transfected cells (Fig. 2c, middle panel), the levels of 65-kDa latent heparanase associated with these as well as all other syndecan variants was above the levels of control (Fig. 2c, upper panel), suggesting that heparanase internalization rather than binding was impaired. In order to better elucidate heparanase localization, U87 cells over-expressing the syndecan-1 variants were incubated with heparanase for 1 h at 37 °C, fixed, and subjected to immunofluorescent staining. Typical staining of heparanase in peri-nuclear vesicles was noted in control cells (Fig. 3, Hepa, Mock). Heparanase staining intensity and the number of peri-nuclear vesicles was increased nearly fourfold in cells over-expressing wild-type syndecan-1 (Fig. 3a, WT, upper and second panels) determined by quantification of heparanase-positive (green) peri-nuclear vesicles (Fig. 3b, WT), an increase that was statistically highly significant (p = 1.8 × 10−8). A similar increase of heparanase internalization was noted following the addition of heparanase to MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma cells over-expressing syndecan-1, co-localizing with syndecan in peri-nuclear vesicles (Fig. 3c, WT). The syndecan-1-positive vesicles observed following the addition of heparanase also co-localized with LAMP1 (Fig. 3d, Hepa), a marker for lysosomes. In striking contrast, heparanase was mostly retained at the cell membrane in cells over-expressing syndecan-1 deleted for the entire cytoplasmic tail, co-localizing with syndecan-1 (Fig. 3a, Delta, upper panel); likewise the formation of heparanase-positive peri-nuclear vesicles in these cells was markedly reduced compared with cells over-expressing WT or C1 variants of syndecan-1, approaching the level in control cells (Fig. 3b; Delta; p = 0.001 for WT vs. Delta). Similarly, heparanase resided predominantly at the cell membrane in cells over-expressing syndecan-1 deleted for the variable region (Fig. 3a, V, upper panel) or C2 domain (Fig. 3a, C2, upper panel), associating with marked decrease in heparanase-positive peri-nuclear vesicles (Fig. 3b; p = 0.95 × 10−8 and 1.3 × 10−6 for WT vs. V and WT vs. C2, respectively), while deletion of the C1 domain did not affect heparanase internalization (Fig. 3a, b, C1). These results closely mimic the FACS and immunoblotting results (Fig. 2a–d) and suggest that syndecan-1 V and C2 domains are required for internalization of heparanase and its delivery to endocytic vesicles and, subsequently, processing and activation.

Fig. 3.

a Immunofluorescent staining. Heparanase (1 μg/ml) was added to U87 glioma cells over-expressing syndecan-1 variants for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were then fixed with cold methanol and subjected to immunofluorescent staining applying anti-heparanase mouse monoclonal antibody (middle panels, green). Merged images with rat anti-syndecan staining (lower panels, red) are shown in the upper panels. Note retention of heparanase at the cell membrane, co-localizing with syndecan lacking the entire cytoplasmic tail (Delta), the V region or C2 domain and increased heparanase-positive endocytic vesicles in cells over-expressing wild-type (WT) or C1 variants of syndecan-1. Quantification of heparanase-positive (green) peri-nuclear endocytic vesicles is shown graphically in (b) as average of at least 12 representative cells. *p = 1.8 × 10−8 for Mock vs. WT; **p = 0.001, 0.95 × 10−8, and 1.3 × 10−6 for WT vs. Delta, WT vs. V and WT vs. C2, respectively. c MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma cells. Heparanase (1 μg/ml) was added to MDA-MB-231cells over-expressing wild-type syndecan-1 (WT), or control mock transfected cells for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were then fixed and subjected to immunofluorescent staining applying anti-heparanase (green; middle panels) and anti-syndecan-1 (lower panels, red) antibodies. Merged images are shown in the upper panels. Note co-localization of heparanase and syndecan in endocytic vesicles but not on the cell membrane. d Heparanase was similarly added to parental MDA-MB-231 cells expressing endogenous levels of syndecan-1 for 1 h; cells were fixed with methanol and subjected to immunofluorescent staining applying anti-LAMP1, a lysosomal marker (middle panels, red) and anti-syndecan-1 (lower panels, green) antibodies. Merged images are shown in the upper panels. Note co-localization of syndecan-1 with LAMP1

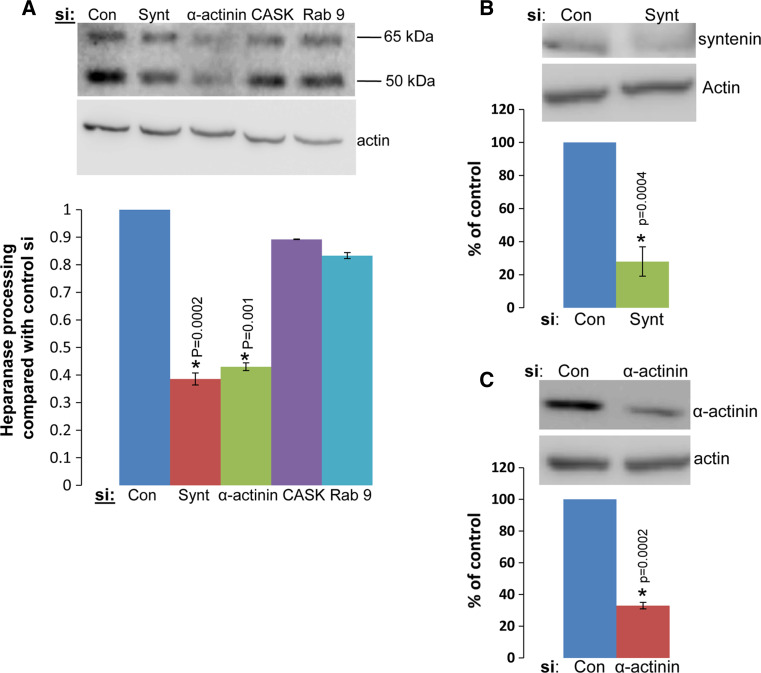

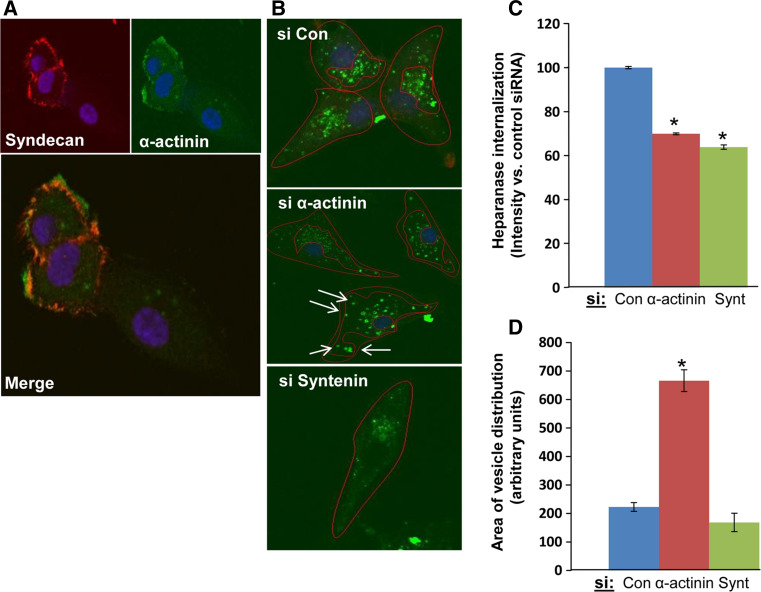

Heparanase internalization and processing are mediated by syntenin and α-actinin

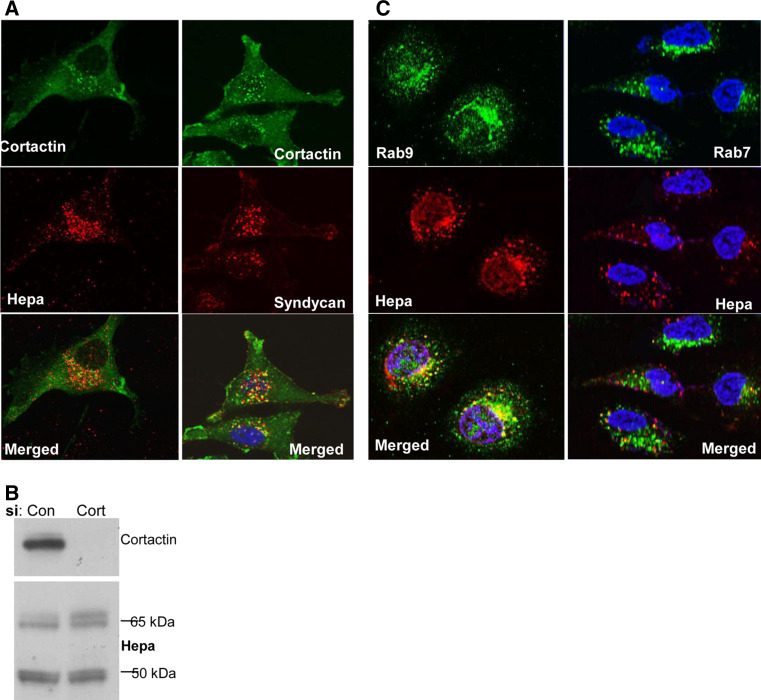

The requirement of syndecan-1 cytoplasmic tail for heparanase internalization noted above strongly suggests the involvement of adaptor proteins that mediate the fate (i.e., membrane-tethered vs. internalization) of the heparanase-syndecan-1 complex. We utilized immunofluorescent staining to examine whether known syndecan-1 adaptor proteins co-localize with syndecan and thus are potentially involved in heparanase uptake. We first examined the role of cortactin in heparanase uptake because Chen et al. [23] have recently shown a role for cortactin in syndecan-1-mediated endocytosis of large multivalent lipoproteins. We found that cortactin resides in peri-nuclear endocytic vesicles following addition of heparanase, co-localizing with heparanase (Fig. 4a, left panel) and syndecan-1 (Fig. 4a, right panel). Notably, however, heparanase processing appeared unchanged in cells treated with anti-cortactin siRNA (Fig. 4b, lower panel), in spite of a marked reduction of cortactin expression (Fig. 4b, upper panel). Similarly, we found that Rab9, and to a lesser extent Rab7, implicated in directing vesicles to the lysosome [32–34], co-localize with heparanase in endocytic vesicles (Fig. 4c), yet heparanase processing was not altered in cells treated with anti-Rab9 siRNA (Fig. 5a, Rab9). In contrast, heparanase processing was decreased over twofold in cells treated with anti-syntenin or anti-α-actinin siRNAs (Fig. 5a), in accordance with a 3–4-fold decrease in syntenin (Fig. 5b, upper panel) and α-actinin (Fig. 5c, upper panel) expression. Immunofluorescent staining revealed that α-actinin co-localizes with syndecan-1 at the cell membrane (Fig. 6a). Notably, heparanase-positive vesicles in cells treated with anti-α-actinin siRNA appeared fewer (Fig. 6b, second panel; Fig. 6c, upper panel, α-act.; p = 0.0002), smaller, and more scattered (i.e., dispersed in the cell cytoplasm, residing also at the cell periphery compared with peri-nuclear accumulation in control cells) than control siRNA (Fig. 6c, lower panel; p = 1 × 10−5). Similarly, decreased heparanase-positive vesicles was noted in cells treated with anti-syntenin siRNA (Fig. 6b, lower panel; Fig. 6c upper panel; p = 0.0001), thus implying that syndecan-1 binding proteins, syntenin and α-actinin, mediate heparanase processing.

Fig. 4.

Heparanase uptake is not mediated by cortactin. a Immunostaining. Heparanase (1 μg/ml) was added to parental U87 cells expressing endogenous levels of syndecan-1 for 2 h at 37 °C. Cells were then fixed in cold methanol and double stained for heparanase (left middle panel, red) or syndecan-1 (right middle panel, red) and cortactin (upper panels, green). Merged images are shown in the lower panels. Note co-localization of cortactin and heparanase or syndecan-1 in endocytic vesicles. b Immunoblotting. 293 cells were transfected with anti-cortactin (Cort) or control (Con) siRNA. Three days thereafter, heparanase (1 μg/ml) was added for 2 h at 37 °C and lysate samples were subjected to immunoblotting applying anti-cortactin (upper panel) and anti-heparanase (second panel) antibodies. c Heparanase (1 μg/ml) was similarly added to U87 cells for 2 h at 37 °C. Cells were then fixed and double stained with anti-heparanase (middle panels, red) and anti-Rab9 (left upper panel, green) or anti-Rab7 (right upper panel, green) antibodies

Fig. 5.

Heparanase uptake is mediated by syntenin and α-actinin. a Immunoblotting. 293 cells were transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides against the gene indicated or control siRNA. After 3 days, heparanase (1 μg/ml) was added at 37 °C for 2 h and cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting applying anti-heparanase (upper panel) or anti-actin (second panel) antibodies. Densitometry analysis of the 50-kDa processed heparanase band in five independent experiments is shown graphically in the lower panel. Gene silencing of syntenin (Synt) and α-actinin (α-act) resulted in a 2.5-fold decrease in heparanase processing (p = 0.0002 and p = 0.001 for siCon vs. siSyntenin and siCon vs. siα-actinin, respectively). b, c 293 cells were similarly transfected with anti-syntenin (b) or anti-α-actinin (c) siRNAs and lysate samples were subjected to immunoblotting applying anti- syntenin (b, upper panel), anti-α-actinin (c, upper panel), and anti-actin (lower panels) antibodies. Attenuation of heparanase processing (a) correlates with a comparable decrease of syntenin and α-actinin expression levels (p = 0.0004 and p = 0.0002 for siCon vs. siSyntenin and siCon vs. siα-actinin, respectively; b, c, lower panels)

Fig. 6.

a α-actinin immunostaining. U87 glioma cells were subjected to immunofluorescent staining applying anti-syndecan-1 (Synd; upper left panel, red) and anti-α-actinin (upper right panel, green) antibodies. A merged image is shown in the lower panel. Note co-localization of α-actinin and syndecan-1 at the cell membrane. b Heparanase immunostaining. U87 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNA oligonucleotides. Heparanase (1 μg/ml) was added 3 days later for 2 h at 37 °C. Cells were fixed with cold methanol and subjected to immunofluorescent staining applying anti-heparanase monoclonal antibody. The intensity and scattering (i.e., distribution of the vesicles within the cell) of heparanase-positive endocytic vesicles were quantified and presented graphically in panels c and d, respectively. Heparanase-positive endocytic vesicles are significantly decreased following α-actinin and syntenin gene silencing (p = 0.0002 and p = 0.0001 for siCon vs. siα-actinin and siCon vs. siSyntenin, respectively; c). α-actinin silencing is also associated with more diffused (scattered) heparanase-positive vesicles (arrows) compared with peri-nuclear accumulation in control cells (p = 1 × 10−5) (d)

Discussion

Syndecans are a family of four transmembrane proteins capable of carrying chondroitin sulfate (CS) and HS chains. The presence of HS chains allows interactions with a large number of proteins including, among others, heparin-binding growth factors, plasma proteins such as antithrombin and atherogenic lipoproteins, extracellular matrix proteins including fibronectin, and pathogens such as viruses and bacteria [35–38]. Binding of many of the above ligands leads to syndecan-mediated endocytosis and catabolism, or orchestration of signaling cascades [39]. Structurally, all syndecans are composed of an extracellular domain, membrane domain, and a conserved short C-terminal cytoplasmic domain divided into the first conserved region (C1), the variable domain (V), and the second conserved region (C2). Each of these cytoplasmic domains has been shown to interact with specific adaptor molecules and to mediate cellular function [29, 30, 40, 41], yet none of these functions had been directly linked to the process of endocytosis until recently [23]. Here, we describe for the first time a role of syntenin and α-actinin in syndecan-mediated endocytosis, leading to heparanase processing and activation. Such a mechanism may be held responsible for the uptake of other syndecan ligands, including harmful pathogens, possibly enabling intervention.

Heparanase interacts with syndecans by virtue of their HS content and the typical high affinity that exists between an enzyme and its substrate. This high-affinity interaction directs rapid and efficient cellular uptake of the heparanase-syndecan complex [4, 22]. Peptide corresponding to the heparin/HS binding domain of heparanase (termed KKDC) similarly associates with the plasma membrane and induces clustering of syndecans, resulting in Rac1 activation and improved cell spreading [9, 16, 25]. Notably, syndecan clusters formed by the KKDC peptide were exceptionally large and failed to be internalized [19, 25]. Likewise, heparanase-2 (Hpa2), a close homolog of heparanase, binds HS with high affinity but fails to get internalized [15], implying that interaction and clustering per se are not sufficient for the internalization of syndecan and this cargo.

Over-expression of syndecan-1 resulted in a marked increase in heparanase binding (Fig. 2c, upper panel, WT), internalization (Fig. 3a, WT), processing (Fig. 2c, middle panel, WT), and enzymatic activity (Fig. 2e), suggesting that the level of cell membrane HS is a rate-limiting step for ligand binding. This stands in contrast to early observations in which internalization of bFGF appeared nonsaturable in the absence of heparin but became saturable in its presence (i.e., upon binding to bFGF high-affinity receptors) [42]. The magnitude of heparanase activation as reflected by syndecan levels may turn important in conditions where syndecan expression is altered. For example, over-expression of syndecan-1 has been observed in pancreatic, gastric, and breast carcinomas, correlating with increased tumor aggressiveness and poor clinical prognosis; syndecan-2 is often over-expressed in colon carcinoma, and syndecan-4 is up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma [29], possibly leading to increased heparanase uptake and activation. Indeed, heparanase expression in these carcinomas most often coincides with disease progression and reduced patient survival [22, 43, 44]. In other cases (i.e., head and neck and lung carcinomas, laryngeal cancer, malignant mesothelioma), however, loss of syndecan-1 expression was associated with disease progression [29, 39], thus illustrating the complexity of HS function in cancer and possibly a redundancy among HSPGs.

While heparanase binds all the syndecan-1 variants to comparable extent when incubated on ice (Fig. 2a, b), internalization of the heparanase-syndecan-1 complex appears to require specific domains of the syndecan-1 cytoplasmic tail. A marked increase in heparanase-positive endocytic vesicles is observed in cells over-expressing wild-type syndecan-1 (Fig. 3a, b, WT) compared with control cells (Fig. 3a, b, Mock). In striking contrast, heparanase is retained on the cell membrane, co-localizing with syndecan-1 lacking the cytoplasmic tail (Fig. 3a, Delta). The low level of heparanase-positive peri-nuclear vesicles observed in these and control (Mock) cells is due to endogenous syndecans [8]. Interestingly, the membrane-tethered 65-kDa heparanase appears unstable because its level is reduced substantially compared with cells over-expressing wild-type syndecan-1 (Fig. 2c, upper panel, WT vs. del), in contrast with comparable binding capacity at conditions (4 °C) that prevent internalization (Fig. 2a, b). A similar decrease was noted for membrane-tethered hparanase-2 [15], suggesting that syndecan ligands that fail to get internalized are removed by extracellular proteases or sheddases. Studies aimed to identify such a protease/sheddase are currently in progress.

Importantly, heparanase was retained at the cell membrane and its internalization was impaired upon deletion of the V region or C2 domain of syndecan-1(Fig. 3, C2, V), accompanied by reduced heparanase-positive peri-nuclear endocytic vesicles (Fig. 3b) and heparanase processing into 50-kDa active enzyme (Fig. 2c, d). These results thus suggest that the C2 and V regions of syndecan-1 play a role in heparanase endocytosis and activation (Fig. 2d) and led us to search for adaptor proteins that mediate syndecan-1 endocytosis.

Unlike large, multivalent lipoproteins [23], heparanase seems to utilize coated pits rather than rafts as the primary endocytosis route. This was concluded from sucrose gradient studies following heparanase uptake, where heparanase appeared to reside predominantly in non-raft fractions [20]. Similarly, we have found that heparanase uptake is decreased following potassium or sucrose depletion, conditions that disrupt coated pits [45], while treatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin that depletes cholesterol and disrupts rafts formation did not significantly reduce heparanase uptake (data not shown).

In Xenopus, syndecan-4 was reported to utilize clathrin-coated pits-mediated endocytosis of Wnt ligand, Rspo3, to promote Wnt activation and signaling [19]. In this system, blocking clathrin-mediated endocytosis was also associated with accumulation of the Rspo3 on the cell surface and reduced Wnt signaling (i.e., JNK activation [19]), closely resembling the accumulation of heparanase on the surface of Delta, C2, and V syndecan mutant cells (Fig. 3a). Thus, syndecans gets internalized via diverse routes depending on their ligand cargo, utilizing different syndecan-1 domains and adaptor molecule. Clearly, large multivalent ligands such as certain lipoproteins elicit syndecan-1 internalization via rafts that involves Erk and Src signaling because inhibitor of these kinases attenuated the internalization while ligand binding was not changed [23]. Most importantly, alanine scanning mutagenesis of the syndecan-1 cytoplasmic tail identified a novel juxtamembrane motif within the C1 domain, MKKK, that was the only region required for efficient endocytosis after clustering [23]. The mechanism by which the MKKK motif elicits endocytosis of syndecan following clustering was elucidated to high resolution and involves two stages. In the initial phase, ligands trigger rapid MKKK-dependent activation of Erk and the localization of syndecan-1 into rafts; in the second phase, syndecan-1 gets phosphorylated by Src kinase in a manner that also requires the MKKK motif [23]. These signaling events are accompanied by dissociation of syndecan-1 from α-tubulin and subsequently the recruitment of cortactin that was found to be an essential mediator of efficient actin-mediated endocytosis [23].

Although our current studies co-localized cortactin with heparanase and with syndecan-1 in endocytic vesicles, cortactin did not appear to be involved in syndecan-mediated endocytosis of heparanase because processing of the enzyme was indistinguishable in magnitude following cortactin gene silencing (Fig. 4a, b). Thus, co-localization with cortactin is consistent with prior literature [23], and the lack of an effect of cortactin knock-down on heparanase processing is consistent with the lack of a role for the C1 domain (where the cortactin-binding sequence, MKKK, is found) in our experimental setting (Figs. 2, 3). Similarly, gene silencing of Rab9 that co-localized with heparanase in endocytic vesicles (Fig. 4c) and of CASK, known to bind the C2 domain of syndecan, had no effect on heparanase uptake (Fig. 5a). In contrast, heparanase processing was found to be mediated by the syndecan-1 adaptor molecule syntenin and α-actinin (Fig. 5a). α-actinin was co-localized with syndecan-1 at the cell membrane (Fig. 6a). Importantly, α-actinin gene silencing was associated with reduced and more diffused heparanase-positive endocytic vesicles (Fig. 6b, c), possibly due to disruption of syndecan-1 interaction with the actin cytoskeleton. This complies with previous results in which heparanase uptake was significantly reduced following disruption of the actin, but not microtubules, cytoskeleton [6]. Syntenin is a PDZ-domain-containing protein that was originally identified as a melanoma differentiation-associated gene (mda-9). Subsequently, syntenin has been shown to interact with a plethora of proteins including the C2 domain of syndecans [46]. This interaction appears not to be responsible for syndecan internalization but rather syndecan recycling back to the plasma membrane [47]. Reduced heparanase uptake following syntenin gene silencing (Fig. 6b, c) suggests that this adaptor molecule is more directly involved in syndecan-mediated endocytosis, in agreement with the necessity of the C2 domain of syndecan-1 for heparanase uptake (Figs. 2, 3). Notably, the decreases in heparanase processing following syntenin or α-actinin gene silencing exceeded the reduction of internalization (Fig. 5a vs. Fig. 6c), suggesting that syntenin and α-actinin may direct heparanase to the lysosome. This is supported by the scattered appearance of heparanase-positive vesicles following α-actinin gene silencing (Fig. 6d). Interestingly, syntenin expression is increased in metastatic cell lines. Furthermore, over-expression of syntenin in non-metastatic cells resulted in increased cell motility, anchorage-independent growth, and spontaneous melanoma metastasis to the lungs [46, 48], closely resembling the role of heparanase in tumor progression [32, 34, 35]. This may imply that like syndecan, syntenin levels may promote tumor progression by modulating heparanase uptake, activation, and extracellular retention.

These results suggest that heparanase utilizes a raft-independent route for internalization by syndecan-1 that leads to processing rather than total destruction in lysosomes. Thus, at least two different syndecan-1-mediated endocytic pathways exists, one that relies on the C1 domain and utilizes a rafts-MKKK-cortactin axis [23] and a second, raft-independent, route that is mediated by the C2 and V domains of syndecan-1 and involves α-actinin and syntenin, leading to heparanase processing and activation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

U87 glioma cells over-expressing the syndecan-1 variants were plated on glass coverslips for 24 h. Cells were then fixed and subjected to immunofluorescent staining applying anti-vinculin antibody (A, lower panels, green) and TRITC-phalloidin (A, upper panels, red). The number of vinculin-positive focal contacts, counted in at least 12 cells, is shown graphically in panel (B). Note increased vinculin staining in cells over-expressing wild-type syndecan-1 and decreased staining following deletion of the entire cytoplasmic tail (Delta) or the V region (V). p = 0.001, 0.01, and 0.05 for Mock vs. WT, Mock vs. V, and Mock vs. Delta, respectively (TIFF 1426 kb)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation (Grant 593/10); National Cancer Institute, NIH (Grant CA106456); the Israel Cancer Research Fund (ICRF); the German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development (GIF), and the Rappaport Family Institute Fund to I. Vlodavsky. I. Vlodavsky is a Research Professor of the ICRF.

References

- 1.Dempsey LA, Brunn GJ, Platt JL. Heparanase, a potential regulator of cell-matrix interactions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:349–351. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01619-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parish CR, Freeman C, Hulett MD. Heparanase: a key enzyme involved in cell invasion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1471:M99–M108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(01)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vlodavsky I, Friedmann Y. Molecular properties and involvement of heparanase in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(3):341–347. doi: 10.1172/JCI13662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gingis-Velitski S, Zetser A, Kaplan V, Ben-Zaken O, Cohen E, Levy-Adam F, Bashenko Y, Flugelman MY, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Heparanase uptake is mediated by cell membrane heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44084–44092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402131200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gingis-Velitski S, Zetser A, Flugelman MY, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Heparanase induces endothelial cell migration via protein kinase B/Akt activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23536–23541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nadav L, Eldor A, Yacoby-Zeevi O, Zamir E, Pecker I, Ilan N, Geiger B, Vlodavsky I, Katz BZ. Activation, processing and trafficking of extracellular heparanase by primary human fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2179–2187. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.10.2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vreys V, Delande N, Zhang Z, Coomans C, Roebroek A, Durr J, David G. Cellular uptake of mammalian heparanase precursor involves low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins, mannose 6-phosphate receptors, and heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33141–33148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zetser A, Levy-Adam F, Kaplan V, Gingis-Velitski S, Bashenko Y, Schubert S, Flugelman MY, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Processing and activation of latent heparanase occurs in lysosomes. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2249–2258. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy-Adam F, Abboud-Jarrous G, Guerrini M, Beccati D, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Identification and characterization of heparin/heparan sulfate binding domains of the endoglycosidase heparanase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20457–20466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414546200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldshmidt O, Nadav L, Aingorn H, Irit C, Feinstein N, Ilan N, Zamir E, Geiger B, Vlodavsky I, Katz BZ. Human heparanase is localized within lysosomes in a stable form. Exp Cell Res. 2002;281:50–62. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen E, Atzmon R, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Heparanase processing by lysosomal/endosomal protein preparation. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2334–2338. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abboud-Jarrous G, Atzmon R, Peretz T, Palermo C, Gadea BB, Joyce JA, Vlodavsky I. Cathepsin L is responsible for processing and activation of proheparanase through multiple cleavages of a linker segment. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18167–18176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801327200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abboud-Jarrous G, Rangini-Guetta Z, Aingorn H, Atzmon R, Elgavish S, Peretz T, Vlodavsky I. Site-directed mutagenesis, proteolytic cleavage, and activation of human proheparanase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13568–13575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arvatz G, Shafat I, Levy-Adam F, Ilan N, Vlodavsky I. The heparanase system and tumor metastasis: is heparanase the seed and soil? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30:253–268. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy-Adam F, Feld S, Cohen-Kaplan V, Shteingauz A, Gross M, Arvatz G, Naroditsky I, Ilan N, Doweck I, Vlodavsky I. Heparanase 2 interacts with heparan sulfate with high affinity and inhibits heparanase activity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28010–28019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fux L, Ilan N, Sanderson RD, Vlodavsky I. Heparanase: busy at the cell surface. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuki IV, Kuhn KM, Lomazov IR, Rothman VL, Tuszynski GP, Iozzo RV, Swenson TL, Fisher EA, Williams KJ. The syndecan family of proteoglycans. Novel receptors mediating internalization of atherogenic lipoproteins in vitro. J Clin Invst. 1997;100:1611–1622. doi: 10.1172/JCI119685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuki IV, Meyer ME, Williams KJ. Transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of syndecan mediate a multi-step endocytic pathway involving detergent-insoluble membrane rafts. Biochem J. 2000;351:607–612. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohkawara B, Glinka A, Niehrs C. Rspo3 binds syndecan 4 and induces Wnt/PCP signaling via clathrin-mediated endocytosis to promote morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2011;20:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-Zaken O, Gingis-Velitski S, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Heparanase induces Akt phosphorylation via a lipid raft receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:829–834. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Anderson RG, Russell DW, Schneider WJ. Receptor-mediated endocytosis: concepts emerging from the LDL receptor system. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1985;1:1–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.01.110185.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ilan N, Elkin M, Vlodavsky I. Regulation, function and clinical significance of heparanase in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis. Intl J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:2018–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen K, Williams KJ. Molecular mediators for raft-dependent endocytosis of syndecan-1, a highly conserved, multifunctional receptor. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:13988–13999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.444737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zetser A, Bashenko Y, Edovitsky E, Levy-Adam F, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Heparanase induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression: correlation with p38 phosphorylation levels and Src activation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1455–1463. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy-Adam F, Feld S, Suss-Toby E, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Heparanase facilitates cell adhesion and spreading by clustering of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen-Kaplan V, Doweck I, Naroditsky I, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Heparanase augments epidermal growth factor receptor phosphorylation: correlation with head and neck tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10077–10085. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen-Kaplan V, Jrbashyan J, Yanir Y, Naroditsky I, Ben-Izhak O, Ilan N, Doweck I, Vlodavsky I. Heparanase induces signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) protein phosphorylation: preclinical and clinical significance in head and neck cancer. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:6668–6678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.271346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vlodavsky I (2001) Preparation of extracellular matrices produced by cultured corneal endothelial and PF-HR9 endodermal cells. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. doi:10.1002/0471143030.cb1004s01 (chap 10, unit 10.4) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Beauvais DM, Rapraeger AC. Syndecans in tumor cell adhesion and signaling. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tkachenko E, Rhodes JM, Simons M. Syndecans: new kids on the signaling block. Circulation Res. 2005;96:488–500. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000159708.71142.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKenzie E, Tyson K, Stamps A, Smith P, Turner P, Barry R, Hircock M, Patel S, Barry E, Stubberfield C, Terrett J, Page M. Cloning and expression profiling of Hpa2, a novel mammalian heparanase family member. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:1170–1177. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agola JO, Jim PA, Ward HH, Basuray S, Wandinger-Ness A. Rab GTPases as regulators of endocytosis, targets of disease and therapeutic opportunities. Clin Genet. 2011;80:305–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01724.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zerial M, McBride H. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:107–117. doi: 10.1038/35052055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stenmark H. Rab GTPase as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernfield M, Gotte M, Park PW, Reizes O, Fitzgerald ML, Lincecum J, Zako M. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. An Rev Biochem. 1999;68:729–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Capila I, Linhardt RJ. Heparin–protein interactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:391–412. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020201)41:3<390::AID-ANIE390>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cardin AD, Weintraub HJ. Molecular modeling of protein-glycosaminoglycan interactions. Arteriosclerosis. 1989;9:21–32. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.9.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L. Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) biosynthesis and GAG-binding proteins. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2010;93:1–17. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(10)93001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuster MM, Esko JD. The sweet and sour of cancer: glycans as novel therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:526–542. doi: 10.1038/nrc1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Multhaupt HA, Yoneda A, Whiteford JR, Oh ES, Lee W, Couchman JR. Syndecan signaling: when, where and why? J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60:31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zimmermann P, David G. The syndecans, tuners of transmembrane signaling. Faseb J. 1999;13(Suppl):S91–S100. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9001.s91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roghani M, Moscatelli D. Basic fibroblast growth factor is internalized through both receptor-mediated and heparan sulfate-mediated mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22156–22162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vlodavsky I, Beckhove P, Lerner I, Pisano C, Meirovitz A, Ilan N, Elkin M. Significance of heparanase in cancer and inflammation. Cancer Microenviron. 2012;5:115–132. doi: 10.1007/s12307-011-0082-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vreys V, David G. Mammalian heparanase: what is the message? J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:427–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding Q, Wang Z, Chen Y. Endocytosis of adiponectin receptor 1 through a clathrin- and Rab5-dependent pathway. Cell Res. 2009;19:317–327. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beekman JM, Coffer PJ. The ins and outs of syntenin, a multifunctional intracellular adaptor protein. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1349–1355. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zimmermann P, Zhang Z, Degeest G, Mortier E, Leenaerts I, Coomans C, Schulz J, N’Kuli F, Courtoy PJ, David G. Syndecan recycling is controlled by syntenin-PIP2 interaction and Arf6. Dev Cell. 2005;9:377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boukerche H, Su ZZ, Emdad L, Baril P, Balme B, Thomas L, Randolph A, Valerie K, Sarkar D, Fisher PB. mda-9/Syntenin: a positive regulator of melanoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10901–10911. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

U87 glioma cells over-expressing the syndecan-1 variants were plated on glass coverslips for 24 h. Cells were then fixed and subjected to immunofluorescent staining applying anti-vinculin antibody (A, lower panels, green) and TRITC-phalloidin (A, upper panels, red). The number of vinculin-positive focal contacts, counted in at least 12 cells, is shown graphically in panel (B). Note increased vinculin staining in cells over-expressing wild-type syndecan-1 and decreased staining following deletion of the entire cytoplasmic tail (Delta) or the V region (V). p = 0.001, 0.01, and 0.05 for Mock vs. WT, Mock vs. V, and Mock vs. Delta, respectively (TIFF 1426 kb)