Abstract

Purpose

To investigate whether parents’ previous physical aggression (PPA) exhibited during early adolescence is associated with adolescents’ subsequent parent-directed aggression even beyond parents’ concurrent physical aggression (CPA); to investigate whether adolescents’ emotion dysregulation and attitudes condoning child-to-parent aggression moderate associations.

Methods

Adolescents (N = 93) and their parents participated in a prospective, longitudinal study. Adolescents and parents reported at waves 1–3 on four types of parents’ PPA (mother-to-adolescent, father-to-adolescent, mother-to-father, father-to-mother). Wave 3 assessments also included adolescents’ emotion dysregulation, attitudes condoning aggression, and externalizing behaviors. At waves 4 and 5, adolescents and parents reported on adolescents’ parent-directed physical aggression, property damage, and verbal aggression, and on parents’ CPA

Results

Parents’ PPA emerged as a significant indicator of adolescents’ parent-directed physical aggression (odds ratio [OR]: 1.25, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.0–1.55; p = .047), property damage (OR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.1–1.5, p = .002), and verbal aggression (OR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.15–1.6, p < .001) even controlling for adolescents’ sex, externalizing behaviors, and family income. When controlling for parents’ CPA, previous mother-to-adolescent aggression still predicted adolescents’ parent-directed physical aggression (OR: 5.56, 95% CI: 1.82–17.0, p = .003), and father-to-mother aggression predicted adolescents’ parent-directed verbal aggression (OR: 1.86, 95% CI: 1.0–3.3, p = .036). Emotion dysregulation and attitudes condoning aggression did not produce direct or moderated effects.

Conclusions

Adolescents’ parent-directed aggression deserves greater attention in discourse about lasting, adverse effects of even minor forms of parents’ physical aggression. Future research should investigate parent-directed aggression as an early signal of aggression into adulthood.

Keywords: aggression, adolescence, families, parent-directed aggression, domestic violence, parent-to-child relationship

Child-to-parent aggression is vastly understudied relative to other forms of family aggression [1,2], yet can have serious ramifications, particularly when adolescents rather than younger children aggress against their parents. Whereas 35–40% of young children aggress against parents, often in a flailing, frustrated manner, parent-directed physical aggression becomes more atypical with age, occurring in approximately 10%–20% of adolescents [3–6]. Conflict between adolescents and parents is quite common. However, distinctions are necessary between everyday disagreements and adolescents who physically lash out against their parents. When adolescents’ size and strength rival that of their parents, there is risk of physical injury to parents, not just children. Adverse health consequences of adolescent-to-parent aggression also include the toll on individual family members’ psychological wellbeing and on family relations [1]. Parents’ embarrassment and confusion about their adolescents’ aggression, as well parents’ and health care workers’ ambiguity about who is responsible for the adolescents’ aggression, may account, in part, for the relative inattention to this topic by clinicians and researchers [7].

Theoretically, parent-directed aggression has been attributed to growing up in aggressive families and learning by example that family aggression is acceptable. Data supporting this explanation show positive links between children’s aggression toward parents and parents’ aggression that the child has directly experienced or witnessed [4–6,8–10]; however, this link is not always supported [9,11]. Previous findings have generally been limited due to cross-sectional or retrospective designs [3–5,12–14], thus making it difficult to rule out actual or perceived bidirectional aggression, or aggression as self-defense. Previous research also has focused on restricted samples of psychiatrically-referred children [11,12,14–16] or juvenile offenders [2,17], thereby promoting the idea that parent-directed aggression occurs in behaviorally-disordered rather than typically developing youth. Some studies also include only male children [18,19], or only mothers [5]. In the present study, we use a prospective multi-wave design with a non-treatment sample of community-based adolescents to provide in-depth analysis of the relative influence of four types of parents’ previous physical aggression—mother-to-child, father-to-child, mother-to-father and father-to-mother—on adolescents’ aggression toward parents.

Beyond parental influences, we investigate two adolescent characteristics—poor emotional regulation and attitudes condoning child-to-parent aggression—as indicators of adolescents’ parent-directed aggression. Parents’ aggression has been linked to children’s emotion dysregulation and attitudes condoning aggression [20–24]. Nonetheless, these characteristics vary widely in children exposed to parents’ aggression and may moderate the effects of such exposure. Adolescents who have not developed emotion regulation skills may be less tolerant of stress overall and may be highly reactive to anger-evoking situations with their parents [5,11]. Likewise, children and adolescents who espouse attitudes supporting aggressive strategies tend to behave more aggressively [21,14], although this association has not been tested with parent-directed aggression.

Three other variables—children’s overall aggressive dispositions, sex, and family economic status—have been associated with parent-directed aggression and are included here as control variables. Due to the conceptual and measurement overlap between aggressive, antisocial behavior and parent-directed aggression [7,11], we include overall externalizing behaviors in our models. Although the most common pattern of parent-directed aggression is male children to their mothers [2,6,17], some studies show no sex differences [4,5,25], and aggression to fathers is more common in older adolescents [19]. These mixed findings underscore the importance of examining adolescent sex for main effects and interactive effects with parent aggression variables. Previous research also indicates that children who aggress against parents tend to come from higher socioeconomic status families, a finding attributed to permissive parenting [3,11].

This prospective, longitudinal study is designed to provide a clearer understanding of longitudinal influences and underlying mechanisms in adolescent-to-parent aggression by testing the following hypotheses:

That parents’ previous physical aggression (PPA) increases the risk for adolescent-to-parent aggression even after controlling for overall adolescent externalizing behavior, sex, and family income. As the first investigation of mothers’ and fathers’ aggression in marital and parent-child family subsystems, we do not have hypotheses comparing the relative importance of different parent PPA variables.

That emotion dysregulation and attitudes condoning child-to-parent aggression have direct effects and moderate the effects of parental aggression on adolescent-to-parent aggression.

That parents’ concurrent physical aggression (CPA) attenuates the influence of parents’ PPA. To fully explore adolescent-to-parent aggression, we separately investigate adolescents’ physical aggression, property damage and verbal aggression toward parents.

METHODS

The study involved three initial data collections (Waves 1–3: mean ages 10.0 [SD = .62], 11.1 [SD = .68], 12.5 [SD = .74]) when we assessed four types of parents’ previous aggression, and two follow-ups (Waves 4–5: mean ages 15.2 [SD = .74], and 18.6 [SD = .80]) when we assessed adolescent-to-parent aggression and parents’ current physical aggression. Wave 3 also included measures of youth’s externalizing behaviors, emotion regulation, and attitudes condoning child-to-parent aggression. The Institutional Review Board approved the protocol for each data collection wave.

Participants

This non-clinical and non-court-referred sample of 93 adolescents (53 males) and their parents volunteered for a longitudinal study on family conflict (N = 119 in the original sample; See [26] for further details). Families were recruited in greater Los Angeles through community advertisements and announcements. Initial inclusion in the larger study required having a child aged 9–10 residing with two parents. Eligibility for the present study required families to complete Waves 1–3 (n = 98); of those eligible, 93 (94.9%) also participated in Wave 4 and/or Wave 5. The majority (n = 75; 80.6%) participated in both Waves 4 and 5; 5 participated only in wave 4, and 13 only in wave 5. Thirty-seven percent were Latino; race was 27% African-American/Black; 42% Caucasian; 14% Asian/Pacific-Islander and 17% multi-racial. Total family income at study entry was: 10% < $25,000; 23% $25,000–$50,000; 44% $50,000–$100,000; 23% >$100,000.

Measures

Adolescents’ Parent-Directed Aggression

Table 1 presents the items and percent endorsement for adolescent-to-parent physical aggression (4 items, α = .72), property damage (3 items, α = .54), and verbal aggression (4 items, α = .75). Adolescents reported on their aggression “when having an argument” with either the mother or father through separate questionnaires. Each parent similarly reported the aggression she or he received from the adolescent. To identify those adolescents who aggressed against one or both parents, we considered an item endorsed if either reporter (parent or child) affirmed its occurrence in either Wave 4 and/or Wave 5. Overall, 22% of adolescents aggressed physically—8% against both parents, 8% against mothers only and 6% against fathers only; 59% damaged property—26% involving property of both parents, 22% of mothers only, and 11% of fathers only; and 75% aggressed verbally—48% against both parents, 19% against mothers only, and 8% against fathers only.

TABLE 1.

Percent of Adolescents’ Physical Aggression, Property Damage, and Verbal Aggression Directed Toward Mothers and Fathers

| % of Females Who Are Aggressive to: | % of Males Who Are Aggressive to: | % of Total Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | ||

| Physical aggression | |||||

|

| |||||

| Pushed, grabbed or shoved your mom/dad | 17.5 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 11.3 | 15.1 |

| Threw something at mom/dad out of anger | 10.0 | 10.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 8.6 |

| Slapped your mom/dad | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 |

| Hit your mom/dad | 5.0 | 7.5 | 1.9 | 9.4 | 9.7 |

| Any Physical Aggression | 25.0 | 12.5 | 7.5 | 15.1 | 21.5 |

|

| |||||

| Property Damage | |||||

|

| |||||

| Damaged something in the house or something that belongs to your mom/dad | 17.5 | 17.5 | 15.0 | 20.8 | 32.3 |

| Threw something or slammed something out of anger toward your mom/dad | 37.5 | 25.0 | 34.0 | 26.4 | 44.1 |

| Punched through the wall | 5.0 | 5.0 | 9.4 | 1.9 | 9.7 |

| Any Property Damage | 45.0 | 37.5 | 50.9 | 35.8 | 59.1 |

|

| |||||

| Verbal Aggression | |||||

|

| |||||

| Swore at mom/dad | 47.5 | 40.0 | 32.1 | 20.8 | 48.4 |

| Insulted your mom/dad | 62.5 | 40.0 | 52.8 | 50.9 | 66.7 |

| Insulted or shamed your mom/dad in front of others | 37.5 | 25.0 | 30.2 | 17.0 | 41.9 |

| Called your mom/dad names | 37.5 | 35.0 | 24.5 | 32.1 | 41.9 |

| Any Verbal Aggression | 80.0 | 57.5 | 58.5 | 54.7 | 75.3 |

|

| |||||

| Total Aggression | |||||

|

| |||||

| Any Parent-Directed Aggression | 85.0 | 62.5 | 68.9 | 64.2 | 83.9 |

Differences in endorsement rates of mother- and father-directed aggression were examined separately for girls and boys using McNemar tests adjusted for small numbers of discordant pairs [27]. Girls were significantly more likely to show some form of aggression overall to mothers than to fathers, p = 0.022, and specifically to verbally aggress more against mothers, p = 0.012. Girls did not show a mother-father difference in physical aggression, p = 0.125, or property damage, p = 0.549. Boys, in contrast, did not direct more physical aggression, p = 0.219, property damage, p = 0.115, or verbal aggression, p = 0.791 toward mothers or fathers. Verbal aggression, more common in girls than boys, χ2(1) = 5.17, p = 0.023, was the only boy-girl difference.

Parents’ PPA

At Waves 1–3, both parents and the adolescent reported on mother-to-father and father-to-mother physical aggression over the past 12 months through five items for each parent (e.g., ‘pushed, grabbed, shoved’, ‘hit’, α = .87) from the Conflict Tactics Scales [28]. At Waves 1–3, mother-to-adolescent physical aggression (reported by mother and child) and father-to-adolescent aggression (reported by father and child) was assessed for the past 12 months through two items for each parent (i.e., ‘slapped on arm or leg’, ‘shook’, α = .57) from the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales [29]. Endorsement at different waves ranged from 50–64% for mother-to-child aggression; 40–62% for father-to-child aggression; 25–42% for mother-to-father aggression; and 21–32% for father-to-mother aggression.

At each wave, we created 0–4 scores by assigning a 0 (no physical aggression) or 1 (some physical aggression by ≥ 1 reporter) for each type of aggression. Following studies of dose-response aggression effects [30–32], we created a 0–12 cumulative score summing across the four aggression types and across the three waves (modal score = 4; 7.5% score 0; 3.2% score 12; 50% ≥ 5).

Parents’ CPA

To disentangle the impact of early adolescent exposure to parents’ PPA versus concurrent exposure, we also used the same parent aggression items to create a 0–4 CPA score summing across the four aggression types in Waves 4 and/or 5. To parallel the assessment of parent-directed aggression during Waves 4–5, we assigned a ‘1’ to each type of aggression if any reporter (child or parent) reported its occurrence in either wave. CPA had an actual range = 0–4; 25% ≥ 2).

Other Risks for Parent-Directed Aggression

At Wave 3, we assessed adolescents’ (a) emotion dysregulation through the average of parents’ reports on modified items from the Emotion Regulation Checklist [33] (3 items, α =.71, e.g. ‘goes to pieces under stress’); and (b) adolescents’ attitudes condoning child-to-parent aggression in response to parents’ confrontational behaviors (11 items written for this study, α =.87, e.g., ‘it is okay for a child to hit a parent if the parent hits the child first’).

Covariates

In addition to sex and parent-reported family income, we included Wave 3 externalizing, i.e., overall aggressive and anti-social behavior, through the average of parents’ and adolescents’ reports of the adolescents’ externalizing score on the Child Behavior Checklist (33 items; α =.92) [34–35].

Analyses

We tested all study variables for sex differences through independent samples t-tests and ran bi-variate correlations. Adolescent-to-parent aggression (whether physical aggression, property damage, or verbal aggression) was an ordinal variable in all models: 0 = no aggression; 1= aggression toward one parent; 2= aggression toward both parents. We ran two sets of ordinal logistic regressions: (a) to test parents’ cumulative PPA (0–12 score); and (b) to compare the four separate types of parents’ PPA (mother-to-adolescent, father-to-adolescent, mother-to-father, and father-to-mother). For each analysis, parent-directed aggression was regressed onto a set of covariates (adolescent sex, family income, externalizing behaviors), adolescent characteristics (emotional dysregulation and attitudes condoning child-to-parent aggression), and parents’ PPA. Diagnostic indices of multi-collinearity were acceptable in all models (Variance Inflation Factors ranging from 1.04–1.70).

To test moderators (emotion dysregulation, attitudes condoning aggression, and child sex), we used a procedure that combines Bayesian Information Criterion [36] with a bootstrapped re-sampling with replacement design [37] to handle the limitations of our sample size for simultaneously testing interactions and main effects. This method has been shown to be an effective procedure for comparing non-nested models, maximizing the likelihood that findings can be replicated in other samples, and producing stable parameter estimates when the number of possible predictors is large relative to the number of observations. To isolate the impact of early parental aggression, we re-ran the ordinal logistic regression models including parents’ CPA score (0–4) with (a) the cumulative 0–12 PPA score and (b) the four separate PPA variables.

RESULTS

Table 2 shows significant correlations among the three types of parent-directed aggression (range = .40–.47), and with parents’ PPA (range = .28–.47) and CPA (range = .32–.41). Adolescents’ physical aggression toward parents correlated with mother-to-adolescent aggression whereas adolescents’ property damage and verbal aggression correlated with all four separate types of parent PPA. Parents’ PPA and CPA were associated (.51) suggesting some consistency over time in family exposure to aggression. Adolescents’ externalizing correlated with parent-directed physical aggression and property damage, and with parents’ PPA and CPA. Emotion dysregulation correlated with adolescents’ parent-directed property damage and with parents’ CPA. Attitudes condoning child-to-parent aggression correlated with parents’ aggression but not with any of the adolescent-to-parent aggression variables. Family income was positively associated with attitudes condoning child-to-parent aggression and negatively with externalizing behaviors. All associations were in the expected directions.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Bi-variate Correlations for All Study Variables

| Variable | Mean | SD | Correlations

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |||

| 1. Parent-directed physical aggressionae | .23 | .59 | --- | |||||||||||

| 2. Parent-directed property damageae | .91 | .86 | .46*** | --- | ||||||||||

| 3. Parent-directed verbal aggressionae | 1.02 | .86 | .40*** | .47*** | --- | |||||||||

| 4. Family incomeb | 70.71 | 35.81 | −.06 | −.10 | .14 | --- | ||||||||

| 5. Adolescent externalizingc | 9.72 | 5.73 | .24* | .41** | .19 | −.22* | --- | |||||||

| 6. Emotion dysregulationc | 5.72 | 2.47 | .12 | .26* | .02 | −.02 | .36*** | --- | ||||||

| 7. Attitudes condoning aggressionc | 1.66 | 2.75 | .05 | .08 | .10 | .23* | −.02 | −.13 | --- | |||||

| 8. Parents’ total previous physical aggressionde | 4.83 | 3.02 | .28** | .47*** | .38*** | −.15 | .36*** | .16 | .25* | --- | ||||

| 9. Mother-to-adolescent physical aggressionde | 1.70 | 1.15 | .38*** | .43*** | .25* | −.09 | .22* | .11 | .23* | .72*** | --- | |||

| 10. Father-to-adolescent physical aggressionde | 1.48 | 1.17 | .19 | .36*** | .29** | −.11 | .37*** | .17 | .08 | .70*** | .52*** | --- | ||

| 11. Mother-to-father physical aggressionde | .94 | 1.14 | .13 | .25* | .22* | −.12 | .25* | .14 | .18 | .66*** | .18 | .15 | ||

| 12. Father-to-mother physical aggressionde | .71 | .98 | .05 | .22* | .30** | −.17 | .13 | −.01 | .25* | .57*** | .10 | .11 | .62*** | |

| 13. Parents’ concurrent physical aggressionae | .97 | 1.14 | .36*** | .41*** | .32** | .05 | .25* | .28** | .12 | .51*** | .44*** | .19 | .46*** | .26* |

Wave 4–5 data;

Wave 1 data;

Wave 3 data;

Wave 1–3 data;

Spearman rank-order correlations are presented for bi-variate associations involving adolescent aggression variables and family aggression variables; Pearson correlations are presented for bivariate associations not involving aggression variables.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Indicators of Parent-Directed Aggression

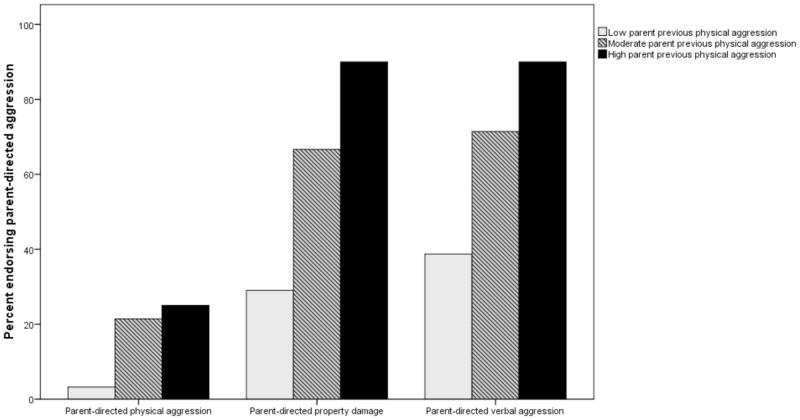

Total PPA emerged as a significant indicator of each form of adolescent-to-parent aggression: for parent-directed physical aggression, OR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.00–1.55, p = .047; for property damage, OR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.10–1.52, p = .002; for verbal aggression, OR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.15–1.58, p < .001. Figure 1 graphically displays these patterns of increasing percentages of adolescents engaging in parent-directed aggression across low (0–3), moderate (4–6), and high (7–12) levels of parents’ total PPA. With low PPA, adolescents were highly unlikely to engage in parent-reported physical aggression (3.2%) and reported modest levels of parent-directed property-damage (29.0%) and verbal aggression (38.7%). Combining those with moderate or high PPA, 22.6% reported parent-directed physical aggression, 74.2% property-damage, and 77.4% verbal aggression.

FIGURE 1.

Percent endorsement of adolescents’ wave 4–5 parent-directed aggression by low (0–3), moderate (4–6), and high (7–12) parent previous physical aggression during waves 1–3

Table 3 summarizes the results when we simultaneously examined the four types of parental aggression. Mother-to-adolescent aggression was the one significant parental indicator for adolescent-to-parent physical aggression and property damage; externalizing was also significant in those analyses. Father-to-mother aggression, along with family income and sex, predicted adolescent-to-parent verbal aggression.

TABLE 3.

Ordinal Logistic Regression Analyses for Parent-Directed Physical Aggression, Property Damage and Verbal Aggression with Separate Parent Previous Physical Aggression Variables

| Parameter | B | SE B | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-Directed Physical Aggression | |||

|

| |||

| Control Variables | |||

| Gender | −0.20 | 0.67 | 0.82 (0.22–3.05) |

| Income | 0.00 | 0.01 | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) |

| Externalizing | 0.14* | 0.07 | 1.15 (1.00–1.32) |

| Child Characteristics | |||

| Emotion Dysregulation | .23 | 0.17 | 1.26 (0.90–1.76) |

| Attitudes Condoning Child-to-Parent Aggression | −0.20 | 0.14 | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) |

| Parents’ Previous Physical Aggression | |||

| Mother-to-Adolescent Physical Aggression | 1.83** | 0.56 | 6.23 (2.07–18.77) |

| Father-to-Adolescent Physical Aggression | −0.25 | 0.34 | 0.78 (0.40–1.53) |

| Mother-to-Father Physical Aggression | 0.02 | 0.38 | 1.03 (0.49–2.16) |

| Father-to-Mother Physical Aggression | −0.13 | 0.42 | 0.88 (0.39–2.00) |

|

| |||

| Parent-Directed Property Damage | |||

|

| |||

| Control Variables | |||

| Gender | 0.16 | 0.45 | 1.18 (0.49–2.81) |

| Income | 0.00 | 0.01 | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) |

| Externalizing | 0.10* | 0.05 | 1.10 (1.01–1.21) |

| Child Characteristics | |||

| Emotion Dysregulation | 0.15 | 0.10 | 1.17 (0.96–1.42) |

| Attitudes Condoning Child-to-Parent Aggression | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.97 (0.83–1.14) |

| Parents’ Previous Physical Aggression | |||

| Mother-to-Adolescent Physical Aggression | 0.70** | 0.23 | 2.02 (1.27–3.20) |

| Father-to-Adolescent Physical Aggression | 0.13 | 0.22 | 1.14 (0.73–1.76) |

| Mother-to-Father Physical Aggression | −0.06 | 0.26 | 0.94 (0.58–1.54) |

| Father-to-Mother Physical Aggression | 0.31 | 0.28 | 1.36 (0.78–2.37) |

|

| |||

| Parent-Directed Verbal Aggression | |||

|

| |||

| Control Variables | |||

| Gender | −0.88* | 0.44 | 0.41 (0.18–0.97) |

| Income | 0.02** | 0.01 | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) |

| Externalizing | 0.09 | 0.05 | 1.09 (0.99–1.19) |

| Child Characteristics | |||

| Emotion Dysregulation | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.98 (0.82–1.18) |

| Attitudes Condoning Child-to-Parent Aggression | −0.09 | 0.08 | 0.92 (0.79–1.07) |

| Parents’ Previous Physical Aggression | |||

| Mother-to-Adolescent Physical Aggression | 0.29 | 0.23 | 1.34 (0.86–2.10) |

| Father-to-Adolescent Physical Aggression | 0.27 | 0.22 | 1.31 (0.84–2.03) |

| Mother-to-Father Physical Aggression | 0.06 | 0.23 | 1.06 (0.68–1.65) |

| Father-to-Mother Physical Aggression | 0.67* | 0.29 | 1.95 (1.10–3.44) |

B is an unstandardized regression coefficient and SE B is the standard error of the unstandardized regression coefficient.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Emotion regulation and attitudes condoning child-to-parent aggression were not significant main effects in these models. In addition, none of the two- or three-way interactions involving parental aggression with emotion regulation, attitudes, or sex emerged as significant or stable predictors.

Parental PPA versus CPA

Parents’ concurrent aggression, when entered without prior aggression, predicted each of the three types of parent-directed aggression: for physical aggression, OR: 1.83, 95% CI: 1.11–3.02, p = .018; for property damage, OR: 2.07, 95% CI: 1.36–3.14, p = .001; and for verbal aggression, OR: 1.78, 95% CI: 1.20–2.65, p = .004. When concurrent parent aggression was entered along with the 0–12 PPA score, neither was significant for parent-directed physical aggression. For property damage, CPA was significant, OR: 1.69, 95% CI: 1.06–2.69, p = .026, and PPA remained close to significance, OR = 1.17, 95% CI: 0.98–1.41, p = .087. For verbal aggression, only PPA was significant, OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.06–1.53, p = .010.

In analyses examining the separate types of PPA, even controlling for CPA, wave 1–3 mother-to-adolescent aggression still predicted adolescents’ parent-directed physical aggression, OR: 5.56, 95% CI: 1.82–17.03, p = .003, and father-to-mother aggression predicted parent-directed verbal aggression, OR: 1.86, 95% CI: 1.04–3.33, p = .036; CPA was not significant in these models. For parent-directed property damage, CPA was significant, OR: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.04–2.78, p = .034, and mother-to-child aggression remained marginally significant, OR: 1.64, 95% CI: 1.00–2.69, p = .051.

DISCUSSION

These results put the spotlight on adolescents’ parent-directed aggression, which to date has been an under-reported and under-studied form of family violence. The findings here suggest strong links between parent-directed aggression and growing up with aggressive parents. Specifically, for each increase on the 0–12 parental aggression index, there was an increased odds of 24% for parent-directed physical aggression, 29% for property damage, and 35% for verbal aggression. These data advance the literature by demonstrating an elevated risk for parent-directed aggression related to prior parental aggression, even after controlling for concurrent parent aggression. Thus, parent-directed aggression is not merely adolescents’ response to ongoing or recent arguments. Our results also demonstrate that parents’ aggression is a significant indicator of parent-directed aggression beyond adolescents’ general propensities for externalizing behavior.

The previous literature generally focuses only on physical aggression toward parents. Three exceptions include: (a) police case reports showing a preponderance of physical assaults (41%) with a small number of verbal threats of assaults (16%) typically by females, and even fewer incidents of property damage (4%) exclusively by males [17]; (b) a Canadian community-based sample of 15–16 year olds’ aggression toward mothers, showing considerably more verbal aggression (64%) than physical aggression (13.8%)[5]; and (c) an Egyptian outpatient sample presenting with first-episode psychosis with the most common abuse being physical/financial abuse to mothers (83.3% of males’ 47.7% of females) compared verbal or psychological abuse [12].

Our community sample also showed non-trivial rates of parent-directed physical aggression (22%). Moreover, property damage (59%) and verbal aggression (75%) were quite pervasive. The commonality of these behaviors, even physical aggression, contradicts accepted ideas that adolescents’ aggression toward parents is rare or only occurs in psychiatric or adjudicated samples. The positive, though small, association between family income and adolescents’ verbal aggression supports previous findings of more parent-directed aggression in White, socially and educationally advantaged families [3,5,15,25]; this finding raises questions about possible economic, cultural, and parenting style influences on parent-directed aggression.

These results are the first to identify mother-to-child aggression as the strongest indicator of both parent-directed physical aggression and property damage; mother-to-child aggression also is significantly associated with attitudes condoning child-to-parent aggression. Further investigation is needed to explain why mothers’ aggression toward their children provides more influential models or shows greater disinhibiting influences on adolescents’ parent-directed aggression. It is possible that adolescents follow the mothers’ example of physical aggression if the consequences are less severe than those resulting from fathers’ physical aggression. It also is possible that adolescents have more contentious relationships overall with their mothers. Yet father-to-mother physical aggression contributed to parent-directed verbal aggression, perhaps reflecting an attitude of disrespect rather than aggression per se. Contrary to previous studies [6,12], our data do not support a pattern of males’ physical aggression primarily toward mothers. Instead, and perhaps indicating societal norms in this non-clinical sample, boys appear to aggress against mothers by damaging property (51%) rather than through physical aggression (8%). More generally, an important future direction for a data set with more power would be to directly compare patterns in adolescents’ aggression toward their mothers versus fathers.

The lack of direct effects and moderation effects for emotion dysregulation and attitudes condoning parent-directed aggression was unanticipated. Emotion dysregulation correlated with adolescents’ property damage but did not account for unique variance in the regression analyses. Moreover, adolescents with more aggression exposure in their history (although not concurrently) were more likely to rate child-to-parent aggression as justifiable. Those attitudes, however, did not translate into actual adolescent-to-parent aggression. Perhaps assessing these variables concurrently with the parent-directed aggression would better test their explanatory influences. Relatedly, better information is needed about what contextual and emotional triggers for parent-directed aggression interact with a family history of aggression exposure.

Limitations and Strengths

First, as is common with family aggression measurements, we have limited information about the immediate events surrounding adolescents’ parent-directed aggression: Who was the initiator? Was substance use a factor [2,5,38]? How did parents respond to adolescents’ aggression? Second, our sample size precluded examining parents’ sex or ethnicity/race as main effects or moderators. Third, it is possible that our dichotomous ‘presence vs. absence’ of each type of parents’ aggression for each wave underestimates the variability and seriousness of certain aggressive patterns. Nonetheless, with overlap among types of family aggression [8,26] and no standard metrics for summing across varying frequencies and intensities associated with different types of aggression, cumulative indices based on dichotomous distinctions are becoming increasing common. Such indices show approximately normal statistical distributions in community samples (i.e., high percentages reporting low-to-moderate aggression) and are related to important outcomes [26,30–32]. Finally, we intentionally designed this study to prioritize two-parent families to assess parent-to-parent aggression, each parent’s aggression toward the adolescent, and aggression directed to both mothers and fathers. Thus, these results do not necessarily generalize to single-parent families where family dynamics may differ.

Despite these limitations, strengths of the study include the prospective design that allows us to compare parents’ prior versus concurrent aggression. With strong associations between previous and current parental aggression, this design ensures that prior aggression is not just a proxy for current aggression. The study also uses multiple reporters to deal with adolescents’ tendencies to underreport aggression and the often-stated concern that parents deny parent-directed aggression due to their own embarrassment [2,5]. This study also offers comprehensiveness and precision about different types of parental aggression as well as different types of parent-directed aggression.

Conclusions

Although instances when young children hit or kick a parent are common and often public occurrences, adolescents’ acts of physical aggression against parents typically occur behind closed doors. Such occurrences may not be disclosed to others if parents believe that they somehow are responsible for their adolescent’s aggressive behavior. Although there is no set age when minor children can be charged with assault of a parent, adolescents’ aggression toward parents may constitute illegal behavior, may cause injury, and may produce fear. Clearly there are complicated questions about culpability given the implicated role of parents’ previous aggression coupled with adolescents’ level of cognitive and psychosocial maturity.

Despite a large available literature on reasons why parents should avoid using physical aggression [39], the risk in-kind of adolescents’ turning aggression directly on their parents deserves greater emphasis. Parent-directed aggression—be it verbal aggression, property-damage, or physical aggression—can have serious implications for parent-adolescent relationships and should be prominent in forthcoming discourse on adverse outcomes associated with parents’ aggression. Beyond links to other forms of family aggression, adolescent-to-parent aggression poses a health risk to both adolescents and parents due to the potential for intentional or inadvertent injury. Long-term consequences of aggressing against one’s parents are as yet unknown but could be noteworthy, particularly if adolescents’ parent-directed aggression is an early warning of future aggression perpetration with intimate partners or their own children.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This study was supported by NIH NICHD grants R01 HD046807, R21 HD072170-A1, F32 HD060410, and the David & Lucile Packard Foundation Grant 00-12802.

The USC Family Studies Project has been funded by NIH Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grants R01 HD046807, R21 HD072170-A1, F32 HD060410) and by funds from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the funders. The authors are grateful to the study families for participation and to the members of the Family Studies Project for their dedication and wisdom.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- CPA

concurrent physical aggression

- OR

odds ratio

- PPA

previous physical aggression

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this manuscript to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Implications and Contribution

Parents’ aggression during early adolescence increases adolescents’ subsequent risk for parent-directed aggression beyond adolescents’ general aggressive tendencies. As an understudied consequence of aggressive parenting, parent-directed aggression may have repercussions for adolescents, parents, and families and may be an early indication of which adolescents are likely to aggress in future relationships.

References

- 1.Hong JS, Kral MJ, Espelage DL, Allen-Meares P. The social ecology of adolescent-initiated parent-abuse: A review of the literature. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43(3):431–54. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0273-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh JA, Krienert JL. Child-parent violence: An empirical analysis of offender, victim, and event characteristics in a national sample of reported incidents. J Fam Violence. 2007;22(7):563–574. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9108-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agnew R, Huguley S. Adolescent violence toward parents. J Marriage Fam. 1989;51(3):699–711. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown KD, Hamilton CE. Physical violence between young adults and their parents: Associations with a history of child maltreatment. J Fam Violence. 1998;13(1):59–79. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pagani LS, Tremblay RE, Nagin D, Zoccolillo M, Vitaro F, McDuff P. Risk factor models for adolescent verbal and physical aggression toward mothers. Int J Behav Dev. 2004;28(6):528–537. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ulman A, Straus MA. Violence by children against mothers in relation to violence between parents and corporal punishment by parents. J Comp Fam Stud. 2003;34(1):41–60. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennair N, Mellor D. Parent abuse: A review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2007;38:203–219. doi: 10.1007/s10578-007-0061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hotaling GT, Straus MA, Lincoln AJ. Intrafamily violence and crime and violence outside the family. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical Violence in American Families. New Brunswick: Transaction; 1990. pp. 431–470. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Neidig P. Disadvantaged youth: Risk factors for perpetrating violence? J Fam Violence. 1995;10(4):379–397. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCloskey LA, Lichter EL. The contribution of marital violence to adolescent aggression across different relationships. J Interpers Violence. 2003;18(4):390–412. doi: 10.1177/0886260503251179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nock MK, Kazdin AE. Parent-directed physical aggression by clinic-referred youths. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;31(2):193–205. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3102_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fawzi MH, Fawzi MM, Fouad AA. Parent abuse by adolescents with first-episode psychosis in Egypt. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(6):730–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kratcoski PC. Youth violence directed toward significant others. J Adolesc. 1985;8(2):145–157. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(85)80043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laurent A, Derry A. Violence of French adolescents toward their parents: Characteristics and contexts. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25(1):21–26. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charles AV. Physically abused parents. J Fam Violence. 1986;1(4):343–355. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harbin HT, Madden DJ. Battered parents: A new syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(10):1288–1291. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.10.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans ED, Warren-Sohlberg L. A pattern analysis of adolescent abusive behavior toward parents. J Adolesc Res. 1988;3(2):201–16. doi: 10.1177/074355488832007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brezina T. Teenage violence toward parents as an adaptation to family strain: Evidence from a national survey of male adolescents. Youth Soc. 1999;30(4):416–444. doi: 10.1177/0044118X99030004002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peek CW, Fischer JL, Kidwell JS. Teenage violence toward parents: A neglected dimension of family violence. J Marriage Fam. 1985;47(4):1051–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deater-Deckard K, Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. The development of attitudes about physical punishment: An 8-year longitudinal study. J Fam Psychol. 2003;17(3):351–360. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Mueller V, Grych JH. Youth experiences of family violence and teen dating violence perpetration: Cognitive and emotional mediators. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2012;15(1):58–68. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kingsfogel KM, Grych JH. Interparental conflict and adolescent dating relationshps: Integrating cognitive, emotional, and peer influences. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18(3):505–515. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.505. DOI: 101037/0893-3200.18.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maughan A, Cicchetti D. Impact of child maltreatment and interadult violence on children’s emotion regulation abilities and socioemotional adjustment. Child Dev. 2002;73(5):1525–1542. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simons DA, Wurtele SK. Relationships between parents’ use of corporal punishment and their children’s endorsement of spanking and hitting other children. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(9):639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paulson MJ, Coombs RH, Landsverk J. Youth who physically assault their parents. J Fam Violence. 1990;5(2):121–133. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Margolin G, Vickerman KA, Oliver PH, Gordis EB. Violence exposure in multiple interpersonal domains: Cumulative and differential effects. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(2):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Straus MA. Measures of intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. J Marriage Fam. 1979;41(1):75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the parent child conflict tactics scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22(4):249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dube SR, Anda RF, Relitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Stud. JAMA. 2001;286(24):3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, Borowsky IW. Adolescent violence perpetration: Associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e778–e786. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mrug S, Loosier PS, Windle M. Violence exposure across multiple contexts: Individual and joint effects on adjustment. Am J Orthopsychiat. 2008;78(1):70–84. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shields A, Cicchetti D. Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Dev Psychol. 1997;33(6):906–16. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Achenbach TM. Manual for Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rafferty AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociol Methodol. 1995;25:111–163. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Austin PC, Tu JV. Automated variable selection methods for logistic regression produced unstable models for predicting acute myocardial infarction mortality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(11):1138–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cotrell B, Monk P. Adolescent-to-parent abuse: A qualitative overview of common themes. J Fam Issues. 2004;25(8):1072–1095. doi: 10.1177/0192513X03261330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gersoff ET. Report on Physical Punishment in the United States: What Research Tells Us About Its Effects on Children. Columbus, OH: Center for Effective Discipline; [Accessed June 8, 2012]. Available at: http://www.phoenixchildrens.com/PDFs/principles_and_practices-of_effective_discipline.pdf. Published 2008. [Google Scholar]