The recruitment of inflammatory cells to the arterial wall and their critical role in increasing plaque size and complexity is now dogma in the field of atherosclerosis 1. Macrophages compose the majority of the inflammatory burden in plaques and incite many of the deleterious responses that exacerbate disease. Thus, the mechanisms by which macrophages are activated to secrete cytokines and other inflammatory mediators are of intense interest. The atherosclerotic milieu is replete with cellular stressors such as modified ApoB-containing lipoproteins (e.g. oxidized LDL) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) which can act as triggers of the inflammatory response. These Danger signals compose a repertoire of triggers of so-called “sterile inflammation” that characterizes atherosclerosis.

The prototypical mediator of sterile inflammation is the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β2. Due to its potent downstream effects, the production of mature, biologically active IL-1β is tightly regulated at two distinct steps 3. In the priming phase, activation of signaling pathways such as NF-κB by Toll-like receptors, other cytokines, or IL-1β itself, leads to the transcriptional induction of precursor IL-1β (pro-IL-1β). Generation of the mature form is then governed by activation of a complex of proteins known as the inflammasome. Although several distinct complexes with unique triggers have been described, the NLRP3 inflammasome composed of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor family member (NLRP3), apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC), and pro-Caspase-1 is the most relevant to metabolic diseases such as atherosclerosis. A variety of pathogen- or endogenously-derived danger signals (known as pathogen- or damage-associated molecular patterns, PAMPs and DAMPs) can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to proteolytic activation of Caspase-1 and consequent cleavage of pro-IL-1β to the mature form 3. The process of inflammasome activation and its contribution to atherogenesis has been the focus of significant recent investigation in the field. Cholesterol crystals, which were previously thought to be inert byproducts of aberrant lipid metabolism in the atherosclerotic plaque, have now been shown to be potent inducers of the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β secretion in macrophages, akin to other crystalline DAMPs 4-6. Even the pro-inflammatory action of oxidized LDL appears to occur in part through CD36-mediated uptake into lysosomes and conversion to cholesterol crystals 7.

Given the ability of IL-1β to further enhance the pro-inflammatory response and recruitment of immune cells, its critical role in exacerbating atherosclerotic progression has long been appreciated 8. Thus, the discovery of endogenous stressors found in the atherosclerotic milieu with profound effects on the macrophage IL-1β response is of significant interest. In this regard, the role of one such cellular stressor, hypoxia, on inflammatory signaling and atherosclerosis is intriguing. The presence of hypoxia, which is observed in both human atheroma and animal models of atherosclerosis, is consequential particularly in advanced plaques with increased hypercellularity and lesion complexity 9, 10. Local hypoxia is thought to arise from a combination of increased metabolic demand in macrophages and reduced oxygen supply stemming from increased diffusion distances across the complex lesion 11, 12. The role of hypoxia as a trigger for numerous atherogenic cellular responses is supported by a large body of literature 13. A universal feature of these responses appears to involve the stabilization and transcriptional activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) 14. At lower oxygen levels, cells are known to produce mitochondrial ROS, leading to the stabilization of HIF-1α15. HIF-1α induces proteolytic, pro-angiogenic, pro-apoptotic, and other destabilizing factors that increase plaque complexity 12, 13. Hypoxia also distinctly alters cellular metabolism, where a shift to anaerobic glycolysis occurs 13. This affects cellular energy balance and the availability of metabolic intermediates required for optimal cellular function. An important outcome is the alteration of macrophage lipid homeostasis toward a foam cell formation phenotype 16. Not surprisingly, hypoxia-induced cellular derangements in the plaque result in accelerated atherosclerosis in several pro-atherogenic animal models 17-19.

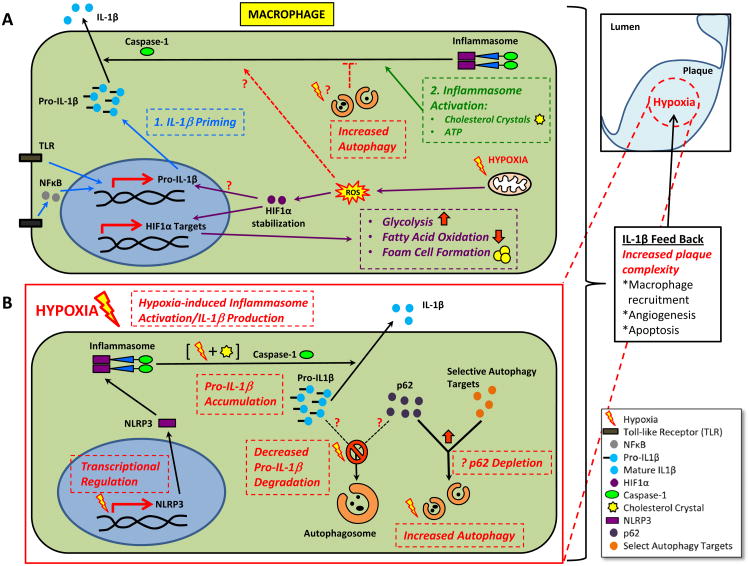

Despite the many parallels between hypoxic and pro-inflammatory effects on plaque progression, few direct links between hypoxia and pro-inflammatory signaling pathways (including IL-1β signaling) have been described 12, 13. Hypoxic conditions can activate the NF-κB pathway through as yet undefined mechanisms 20. Several reports have shown that hypoxia can induce the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines, especially IL-1β 21, 22. Most recently, work by Tannahill, et al detailed a novel mechanism by which lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulates IL-1β transcription through HIF-1α, a process that depends on succinate and metabolic switching of macrophages to glycolysis 23. Although the synergistic secretion of IL-1β upon exposure to both LPS and hypoxia was noted, the specific role of hypoxia in IL-1β transcription was not evaluated. An overview of the current understanding of the regulation of IL-1β production with links to hypoxia in atherosclerotic macrophages is shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1. Current and Proposed View of IL-1β Regulation in the Context of Hypoxia in Atherosclerotic Macrophages.

(A) IL-1β is generated by a 2-step process: 1) priming where pro-IL-1β can be transcriptionally induced by TLR ligands or cytokines, and 2) inflammasome activation where DAMPs such as cholesterol crystals can trigger inflammasome formation, caspase-1 activation, and cleavage of pro-IL-1β to mature/secretable IL-1β. Autophagy is known to be inhibitory to inflammasome activation. The relevant previously described roles of hypoxia are also depicted. Hypoxia can activate autophagy with unknown significance on inflammasome inhibition. Hypoxia can also induce mitochondrial ROS leading to HIF-1α stabilization with potential upregulation of pro-IL-1β transcripts. More characterized downstream effects of the hypoxia/HIF-1α axis are a metabolic shift to glycolysis and alterations in fatty acid metabolism favoring foam cell formation.

(B) The effects of hypoxia at various levels of IL-1β processing as proposed by Folco et al is depicted. Hypoxia can selectively prevent the degradation of pro-IL-1β by limiting its interaction with the p62 chaperone through as yet unclear mechanisms. A possibility is hypoxia-mediated induction of other p62-dependent autophagic degradation processes, limiting p62 availability. Hypoxia can lead to transcriptional induction of NLRP3, a key component of the inflammasome. The combination of hypoxia and known DAMPs such as cholesterol crystals can synergistically activate the inflammasome complex, caspase-1 activation, and cleavage of pro-IL-1β to mature/secretable IL-1β. It is unclear if this activation is solely dependent on increased NLRP3 levels or is further regulated in the cytoplasm.

In the current issue of Circulation Research, Folco et al suggest a novel link between hypoxia, inflammasome activation, and induction of the macrophage IL-1β response 24. In order to gain a holistic understanding of IL-1β production under hypoxic conditions, Folco and colleagues interrogated the effect of moderate hypoxia in human macrophages and plaques at several levels of regulation, including transcription, pro-IL-1β processing, and inflammasome activation. First, they make the interesting observation that hypoxia synergistically elevates LPS-induced pro-IL-1β levels in a manner independent of transcription. Follow-up pulse-chase experiments confirmed slower pro-IL-1β degradation under hypoxia, an observation that implicates either proteosomal or autophagic dysfunction. Several prior reports have suggested a complex role for autophagy in IL-1β production. Autophagy can both facilitate the degradation of pro-IL-1β 25 as well as dampen the ability of the NLRP3 inflammasome to convert pro-IL-1β to its active form 6, 26, 27. Using the potent lysosomal (and by extension, autophagy) inhibitor Bafilomycin, Folco et al note that the profound difference in LPS-induced pro-IL-1β accumulation between hypoxic and normoxic conditions is abrogated. Buttressing their data with two markers of autophagy, p62 and LC3, they conclude that disruption of autophagic degradation is a prominent mechanism by which hypoxia increases pro-IL-1β levels.

At first pass, a hypoxia-mediated disruption of autophagic degradation is at odds with several previous reports demonstrating reduced oxygen levels in potent induction of autophagy, a process that is HIF-1α dependent 28. In agreement with this literature, when Folco et al compare the rate of autophagic flux in their experimental model, the protein levels of two well-known targets of autophagic degradation (p62 and LC3) are indeed reduced under hypoxic conditions, suggesting increased autophagy. How could it be possible that autophagic degradation of pro-IL-1β can have slower kinetics with hypoxia while autophagy pathways are induced? Folco and colleagues suggest that selective autophagy might be the answer. The discriminatory capacity of cells to target specific proteins or organelles for autophagic degradation is known as selective autophagy and a repertoire of proteins have been described to date that mediate this process 29, 30. A well-characterized mechanism for the selective targeting of proteins for autophagic degradation involves protein polyubiquitination, binding to the chaperone p62, and cargo delivery to autophagosomes via p62's LC3-binding domain 29, 30. As evidence for such a process occurring in macrophages, Folco et al use immunofluorescence microscopy to show a loss of p62 co-localization with pro-IL-1β in hypoxic conditions. This observation would imply that with hypoxia, p62's interaction with competing proteins/organelles is favored, thus limiting p62 availability for selective pro-IL-1β degradation. At present, it is unknown whether pro-IL-1β undergoes polyubiquitination and the degree to which it interacts with and is cleared by a p62-dependent process, but this interesting possibility can be further evaluated in vitro (e.g. reconstitution experiments where the ubiquitin-binding domain of p62 is manipulated). It is noteworthy that polyubiquitination of the inflammasome complex and p62-dependent autophagic degradation has also been proposed as an alternative mechanism of limiting IL-1β production 27.

Folco and colleagues go on to implicate hypoxia at another level of IL-1β production, the NLRP3 inflammasome. They show that induction of IL-1β secretion by LPS is synergistically activated only upon incubation of macrophages with the known inflammasome trigger, cholesterol crystals, under hypoxic conditions. They support this finding by demonstrating selectivity for IL-1β (i.e. no changes were noted in TNFα and IL-6), concomitant elevation of cleaved (i.e. activated) caspase-1, an abrogation of this activation by caspase-1 inhibition, and a similar synergistic relationship between hypoxia and another potent inflammasome activator Nigericin. They suggest that at least part of the hypoxia-induced inflammasome hyperactivation is related to transcriptional increases in NLRP3, an essential component of the inflammasome complex. Finally, as a link to the in vivo setting, they demonstrate that cholesterol crystals, IL-1β, activated caspase-1, and several markers of hypoxia such as HIF-1α are highly co-localized to the same macrophage-rich areas of human atherosclerotic plaques. Surprisingly, the IL-1β response of human macrophages to LPS and cholesterol crystals showed mild non-significant elevations, akin to LPS and hypoxia. Although this is distinctly different that the robust elevations of IL-1β when similar assays are conducted in murine macrophages 4, 6, 23, differences in experimental design as the authors suggest or inherent differences between human and murine macrophages might be an explanation. Also the precise mechanism by which hypoxia synergistically activates the inflammasome complex warrants further investigation. Is hypoxia-induced transcriptional upregulation of NLRP3 the predominant reason for enhanced inflammasome activity? Is hypoxia-induced NLRP3 transcription dependent on HIF-1α activation? An enticing alternative mechanism is hypoxia's role in more direct cytoplasmic activation of the inflammasome complex. Lower oxygen levels are a potent trigger for mitochondrial ROS 15 which in turn is one of the most potent triggers of the inflammasome complex 26. Furthermore, cholesterol crystals among other crystalline DAMPs are thought to activate the inflammasome by disrupting the membrane integrity of lysosomes 4. Thus, it would be interesting to evaluate whether hypoxia exacerbates crystalline-mediated lysosomal membrane integrity.

An overview of the role of hypoxia in atherosclerotic macrophage IL-1β production as proposed by Folco and colleagues is shown in Figure 1B. Taken together, these data support the notion that hypoxia imparts similar effects as other DAMPs and relevant inflammasome activators such as cholesterol crystals and implicates hypoxia as a previously unrecognized danger signal in atherosclerosis. In order to control the indiscriminate activation of IL-1β, nature has placed multiple regulatory steps in the processing of this potent pro-inflammatory cytokine. Hypoxia now adds a fascinating twist to the ever-increasing complexity of IL-1β regulation, the mastery of which will expand our understanding of clinically important chronic inflammatory conditions such as atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grant K08HL098559.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Hansson GK, Libby P. The immune response in atherosclerosis: A double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:508–519. doi: 10.1038/nri1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen GY, Nunez G. Sterile inflammation: Sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:826–837. doi: 10.1038/nri2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schroder K, Zhou R, Tschopp J. The nlrp3 inflammasome: A sensor for metabolic danger? Science. 2010;327:296–300. doi: 10.1126/science.1184003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM, Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nunez G, Schnurr M, Espevik T, Lien E, Fitzgerald KA, Rock KL, Moore KJ, Wright SD, Hornung V, Latz E. Nlrp3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajamaki K, Lappalainen J, Oorni K, Valimaki E, Matikainen S, Kovanen PT, Eklund KK. Cholesterol crystals activate the nlrp3 inflammasome in human macrophages: A novel link between cholesterol metabolism and inflammation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razani B, Feng C, Coleman T, Emanuel R, Wen H, Hwang S, Ting JP, Virgin HW, Kastan MB, Semenkovich CF. Autophagy links inflammasomes to atherosclerotic progression. Cell Metab. 2012;15:534–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheedy FJ, Grebe A, Rayner KJ, Kalantari P, Ramkhelawon B, Carpenter SB, Becker CE, Ediriweera HN, Mullick AE, Golenbock DT, Stuart LM, Latz E, Fitzgerald KA, Moore KJ. Cd36 coordinates nlrp3 inflammasome activation by facilitating intracellular nucleation of soluble ligands into particulate ligands in sterile inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:812–820. doi: 10.1038/ni.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masters SL, Latz E, O'Neill LA. The inflammasome in atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:81ps17. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjornheden T, Levin M, Evaldsson M, Wiklund O. Evidence of hypoxic areas within the arterial wall in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:870–876. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.4.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sluimer JC, Gasc JM, van Wanroij JL, Kisters N, Groeneweg M, Sollewijn Gelpke MD, Cleutjens JP, van den Akker LH, Corvol P, Wouters BG, Daemen MJ, Bijnens AP. Hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible transcription factor, and macrophages in human atherosclerotic plaques are correlated with intraplaque angiogenesis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1258–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sluimer JC, Daemen MJ. Novel concepts in atherogenesis: Angiogenesis and hypoxia in atherosclerosis. J Pathol. 2009;218:7–29. doi: 10.1002/path.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulten LM, Levin M. The role of hypoxia in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2009;20:409–414. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283307be8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marsch E, Sluimer JC, Daemen MJ. Hypoxia in atherosclerosis and inflammation. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24:393–400. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32836484a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang HY, Hughes R, Murdoch C, Coffelt SB, Biswas SK, Harris AL, Johnson RS, Imityaz HZ, Simon MC, Fredlund E, Greten FR, Rius J, Lewis CE. Hypoxia-inducible factors 1 and 2 are important transcriptional effectors in primary macrophages experiencing hypoxia. Blood. 2009;114:844–859. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandel NS, Maltepe E, Goldwasser E, Mathieu CE, Simon MC, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11715–11720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parathath S, Yang Y, Mick S, Fisher EA. Hypoxia in murine atherosclerotic plaques and its adverse effects on macrophages. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2013;23:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakano D, Hayashi T, Tazawa N, Yamashita C, Inamoto S, Okuda N, Mori T, Sohmiya K, Kitaura Y, Okada Y, Matsumura Y. Chronic hypoxia accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein e-knockout mice. Hypertens Res. 2005;28:837–845. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savransky V, Nanayakkara A, Li J, Bevans S, Smith PL, Rodriguez A, Polotsky VY. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces atherosclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1290–1297. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1771OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jun J, Reinke C, Bedja D, Berkowitz D, Bevans-Fonti S, Li J, Barouch LA, Gabrielson K, Polotsky VY. Effect of intermittent hypoxia on atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song D, Fang G, Mao SZ, Ye X, Liu G, Gong Y, Liu SF. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces atherosclerosis by nf-kappab-dependent mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:1650–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghezzi P, Dinarello CA, Bianchi M, Rosandich ME, Repine JE, White CW. Hypoxia increases production of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor by human mononuclear cells. Cytokine. 1991;3:189–194. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(91)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carmi Y, Voronov E, Dotan S, Lahat N, Rahat MA, Fogel M, Huszar M, White MR, Dinarello CA, Apte RN. The role of macrophage-derived il-1 in induction and maintenance of angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2009;183:4705–4714. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, Frezza C, Bernard NJ, Kelly B, Foley NH, Zheng L, Gardet A, Tong Z, Jany SS, Corr SC, Haneklaus M, Caffrey BE, Pierce K, Walmsley S, Beasley FC, Cummins E, Nizet V, Whyte M, Taylor CT, Lin H, Masters SL, Gottlieb E, Kelly VP, Clish C, Auron PE, Xavier RJ, O'Neill LA. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces il-1beta through hif-1alpha. Nature. 2013;496:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folco EJ, Sukhova GK, Quillard T, Libby P. Moderate hypoxia potentiates interleukin-1β production in activated human macrophages. Circ Res. 2014;115:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304437. in this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris J, Hartman M, Roche C, Zeng SG, O'Shea A, Sharp FA, Lambe EM, Creagh EM, Golenbock DT, Tschopp J, Kornfeld H, Fitzgerald KA, Lavelle EC. Autophagy controls il-1beta secretion by targeting pro-il-1beta for degradation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9587–9597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2011;469:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi CS, Shenderov K, Huang NN, Kabat J, Abu-Asab M, Fitzgerald KA, Sher A, Kehrl JH. Activation of autophagy by inflammatory signals limits il-1beta production by targeting ubiquitinated inflammasomes for destruction. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazure NM, Pouyssegur J. Hypoxia-induced autophagy: Cell death or cell survival? Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:177–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kraft C, Peter M, Hofmann K. Selective autophagy: Ubiquitin-mediated recognition and beyond. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:836–841. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sergin I, Razani B. Self-eating in the plaque: What macrophage autophagy reveals about atherosclerosis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]