Abstract

Power and organizational hierarchies are ubiquitous to social institutions that form the foundation of modern society. Power differentials may act to constrain or enhance people's ability to make good ethical decisions. However, little scholarly work has examined perceptions of this important topic. The present effort seeks to address this issue by interviewing academics about hypothetical ethical problems that involve power differences among those involved. Academics discussed what they would do in these scenarios, often drawing on their own experiences. Using a think-aloud protocol, participants were prompted to discuss their reasoning and thinking behind their ethical decisions. These interview data were content analyzed using a semantic analysis program that identified a number of distinct ways that academics think about power differences and abuses in ethical situations. Implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: ethics, ethical decision making, power, power differentials

Power has been an important feature of social interactions throughout recorded history. Classically defined as the ability to compel others to do what you want them to do (Dahl, 1957), the construct has been studied across many domains including philosophy, psychology, sociology, economics, gender studies, and marketing (e.g., Connell, 1987; Foucault, 1982; Gaski & Nevin, 1985; Mann, 1984; Olson, 2000; Yukl, 2012). Thanks to such scholarly interest, we have come to a better understanding of how power operates to shape the world around us.

Earlier scholars such as Marx and Weber (e.g., Gerth & Mills, 1991; Marx, 1978) framed history as a perpetual conflict between competing classes, a point still argued in more contemporary work (i.e., Priestland, 2012). Other scholars have argued that history has been written largely from the view of those in power, which has no doubt influenced our understanding of the past (e.g., Zinn, 2005). Underlying such thinking is the idea that power is a ubiquitous aspect of society and a common source of tension in how people have related to each other.

Dahl's definition of power implies the requirement that there must be a dyadic relationship for power to exist, that is, it requires at least two people: somebody who has power, and somebody over whom to have power. Focusing on power as it relates to interpersonal relationships, we see a wide literature illustrating how power impacts the lives and relationships of individuals (e.g., Dunbar & Burgoon, 2005; Oyamot, Fuglestad, & Snyder, 2010). Looking more specifically at power in the workplace, we find a very active literature examining how power relations operate in organizations and what this means for those seeking to understand power (e.g., Jermier, Knights, & Nord, 1994; Skarlicki & Folger, 1997). Unsurprisingly, those without power and in lower roles in organizational hierarchies are often those who experience the negative effects of power relationships such as bullying and oppressive supervision (Hodson, Roscigno, & Lopez, 2006; Jacoby, 2004; Lively, 2002). The purpose of the present effort is to look at power perceptions in a sample of academics to identify how they think about power relationships in ethical situations.

Although the negative effects of power have certainly been examined, work has also been done to understand and broadly classify the distinct types of power that operate in the workplace. French and Raven (1959) identified five bases of power: coercive, reward, legitimate, referent, and expert. Coercive power is the use of force (implied or otherwise) to achieve compliance. Reward power is associated with the ability to give somebody something they want. Legitimate power often comes from a role or position that has authority over other people Referent power is often used by role models or people who are respected. Finally, expert power comes from having large amounts of knowledge or expertise. Framing power in terms of these sources can help us understand how power can be used appropriately or abused.

Power Relationships in Organizations

The concept of power implies hierarchies in which some individuals possess more influence than others in a given situation. It is important to consider that power may act to influence or bias people that possess it. Accordingly, research has examined some of the underlying biases common to people in positions of power. For example, people in positions of power are likely to attend to information that confirms their beliefs (Copeland, 1994), stereotypes the powerless (Goodwin, Gubin, Fiske, & Yzerbyt, 2000), and distributes rewards in ways that favor their own powerful groups (Sachdev & Bourhis, 1985, 1991). Considering these biases, it is unsurprising that power has the potential to be used to negative ends. Business moguls like Bernard Ebbers and Ken Lay bankrupted once powerful companies. Power is also commonly used for positive ends (Mumford, 2006). Leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Franklin D. Roosevelt used their power to make many positive changes in society. Business leaders such as Lee Iacocca and Steve Jobs took companies on the brink of bankruptcy and turned them into empires.

These power differentials are especially common in organizations. Many organizations, including academic ones, are ordered in a hierarchical fashion, with some positions having authority over others, such as the relationship between supervisors and subordinates, professors over students, or senior professors over junior professors. In fact, some scholars have argued that organizations are a unique context regarding power differentials because the structure and role boundaries in organizations are more clear than in other situations (Lindsey, Dunbar, & Russell, 2011). This formalization serves to make power differentials more salient to involved parties.

In many of these relationships, more powerful individuals influence the well-being of less powerful individuals, placing those less powerful individuals in vulnerable positions. The more powerful individual is sometimes tasked with supporting the well-being of the more dependent person, often in a mentoring capacity (Moberg & Velasquez, 2004). Ideally, the more powerful individual guides the person below him or her in terms of developing, training, or support. Research suggests these relationships are important, especially regarding ethical decision making (Gelman & Gibelman, 2002). Although power differentials serve a valuable role in society, they bring certain complications that should be recognized regarding ethical decision making.

Power Abuses in Organizations

Many ethical breaches in organizations can be traced to normal individuals following the orders of a more powerful figure. Many people in high-profile cases such as Enron Corporation and Arthur Anderson attempted to abdicate responsibility, with some juries explicitly noting that defendants lower in the organizational hierarchy were only following orders (Murphy, 2007). These events have two important implications relating to power differentials. First, they suggest that most people are capable of behaving unethically in response to authority, a finding recreated in the laboratory by Milgram (1963) and since replicated (Burger, 2009; Haney, Banks, & Zimbardo, 1973). In these studies, normal people performed actions they would not have believed themselves to be capable of, such as administering painful electrical shocks to other study participants. The second important implication is that the behavior of those in power is often unchecked by subordinates. For instance, if a supervisor commonly relies on coercive power, that individual's subordinates may rightfully fear that reporting ethical breaches by superiors will jeopardize their careers. If a manager relies primarily on expert power, subordinates may defer to their expertise on matters and assume the manager is not doing anything inappropriate. Although there exist other checks from peers or other sources, subordinates are often in the best position to observe their supervisors.

Perceptions of an environment influence behavior. Indvik and Johnson (2009) argued that lying will be a more common occurrence in a work environment than in the home because the workplace is viewed as more impersonal, a perception that would make unethical behavior more common in the workplace. In an impersonal environment we may feel less accountable for our actions, or may view the potential gains from unethical behavior as more salient. Perceptions also act as a powerful influence on behavior when power differentials are involved (Roloff & Cloven, 1990). The perceptions of power differentials are partly driving how people behavior in ethical situations, not solely the formal power differentials themselves. Recognizing that power hierarchies have a significant influence on how people behave in organizations, surprisingly little research has addressed this topic from the perspective of professional ethics.

Academia is one setting that can help us understand this important issue for organizations. Universities are organized to operate as if there were many small organizations embedded within a larger system. The opinions and perceptions of those in academic organizations can help us gain insight into how working professionals view power relationships. A first step to researching this topic is to gain a better understanding of how power differentials are actually viewed by such working professionals. Therefore, this study addresses the question of how academics view power relationships.

Method

To address this research question a diverse set of academics were interviewed in relation to their responses on a measure of ethical decision making in the sciences. The interview itself was part of a larger effort to better understand several issues related to research or scientific ethics. Using content analysis, interviews were reviewed to identify themes in participants' discussion of power relationships.

Sample

Sixty-four faculty members from the University of Oklahoma agreed to participate in our study. This sample consisted of 37 men and 27 women, including 15 assistant professors, 28 associate professors, 20 full professors, and one adjunct professor. The research professionals were grouped into six broad categories: biological sciences, physical sciences, social sciences, health sciences, performance (e.g., drama, music, poetry), and humanities (e.g., history, philosophy). Graduate liaisons from many departments were given a short presentation regarding the nature of the study. In turn, participants were nominated by their graduate liaison from each department to participate. Participants at this point would be asked via e-mail if they would agree to take part in the study.

Ethical Decision-Making Measure

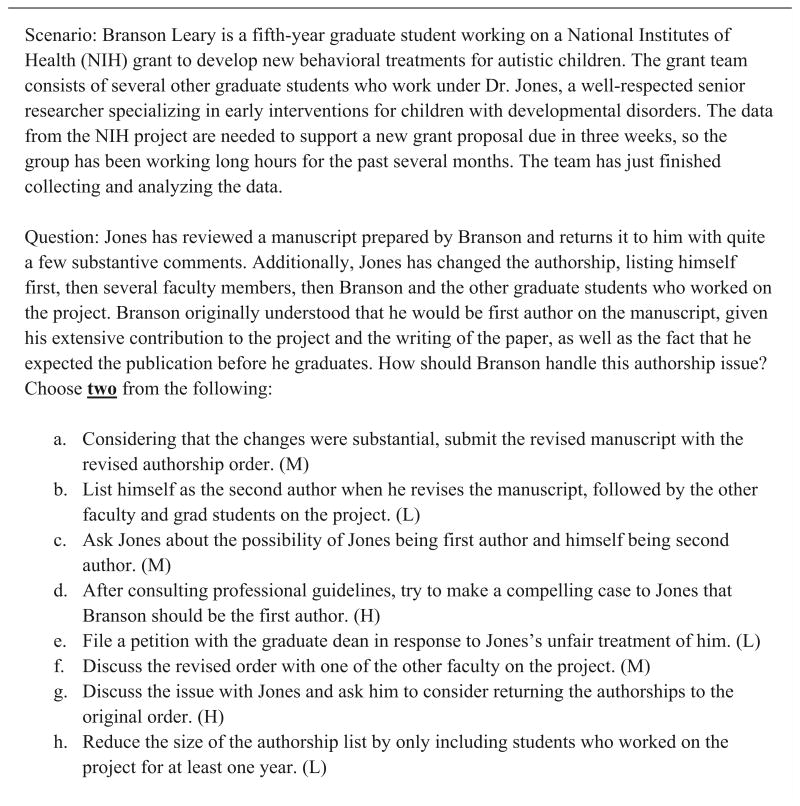

In this study, power differentials were examined in the context of ethical decision making in order to understand the unique effects of power on the ethical dilemmas faced by academics. To prime participants to discuss ethical issues, participants were asked to complete an ethical decision-making instrument developed by Mumford et al. (2006), addressing four general dimensions of professional ethical behavior—data management, study content, professional practices, and business practices. The previously written instrument presented scenarios involving ethical dilemmas in each of these general dimensions for each of the broad areas. Contextual material was adjusted for each of the professional areas in our sample, but the ethical issues embedded in the dilemmas presented were the same. Each of the six instruments presented between four and seven scenarios, each with three to five corresponding questions. An example item is shown in Figure 1. Each participant selected two out of eight responses, all of which reflected responses to the ethical dilemma described in the item. Construct validity evidence, including convergent and discriminant validity, as well as correlations with expected causes and outcomes of ethical decisions, can be found in Mumford et al. (2006) and Antes et al. (2007).

Figure 1.

Sample scenario and question from the social science ethical decision-making measure.

Note. H, M, and L refer to ratings of high, medium, and low ethicality. The ratings were not visible to participants.

Participants completed their field-specific ethical decision-making task through an online survey tool, Qualtics. Upon the completion, tests were scored by totaling the responses to each question into an average score for each scenario. During the validation of this measure, each potential response was rated by subject-matter experts as displaying high, medium, or low ethicality, which corresponded to 1, 2, or 3 points, for scoring purposes. A mean scenario score was calculated by averaging all of the response scores from each scenario. Scenarios on which participants scored significantly higher or significantly lower than their average ethicality score (calculated as a half standard deviation above their mean or a half standard deviation below their mean ethicality score) were selected for inclusion in the interview. The half standard deviation cutoff was practically, and not theoretically, based. Using this cutoff ensured that each participant would have one or two scenarios that qualified for significantly above or below their personal means. Scenarios on which a participant performed especially high or especially low were expected to elicit especially rich discussion, as described next. The purpose of using these critical incidents was to obtain a wide range of responses to explore power perceptions across a range of ethical decision making (i.e., low to high).

Think-Aloud Interviews

Approximately one week following the completion of the online instrument, participants were interviewed regarding the thinking behind the solutions they had selected for the various dilemmas presented in the scenarios for which they scored above or below their overall average. Interviewers were blind as to whether a scenario being discussed was solved well or poorly. Talking through their reasoning served as a springboard for more wide-ranging discussion by participants about the issue at hand. To encourage more thorough and thoughtful responses, interviewers used several probe questions. These probe questions were grouped into two categories: general questions and deep questions. A comprehensive list of probe questions can be found in Table 1. General questions were broad queries that were asked with the intention of letting the participants explain their reasoning and thinking with as little structure as possible. Examples of a general probe question would be, “How did you arrive at those answers?” and “What were your thoughts when you chose this answer?” Deep questions were asked to help more reticent or concise interviewees elaborate on their original explanations. Examples of a deep probe question would be something along the lines of “What dilemma did you see with these answers?” and “When have you seen someone in a similar scenario make poor decisions? What did they do or not do?” No direct questions related to power and power relationships were asked to avoid unnecessarily priming participants. Instead, power was often an important aspect of the scenarios and participants would raise the issue organically, without any prompting by interviewers.

Table 1. Interview Questions.

| General Questions | Deep Questions |

|---|---|

|

|

The interviewers were doctoral students familiar with the ethical decision-making literature. Training for these individuals was conducted over a 2-month period before any actual interviews took place. Interviewers first practiced interviewing each other and recorded these interviews for review. After sufficient practice with each other, the four interviewers practiced interviewing two volunteer faculty otherwise uninvolved with the research project. All actual interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed.

Content Analysis

Interview transcripts were content analyzed using semantic analysis software, NVivo 10, to identify the presence of discussions relating to power differentials. To facilitate this processes, keywords were generated that would help in the identification of such discussions (Fielding & Lee, 1998). A preliminary list of keywords related to power differentials were written and run through NVivo. This process identified where a participant discussed power differentials and helped discover new keywords for future searches. After this process, a list of keywords was reviewed by subject-matter experts in the area of ethical decision making and altered according to their suggestions. This panel of subject-matter experts was composed of a chaired professor, a full professor, and an associate professor. A list of these keywords can be found in Table 2. Keywords would include searches for terms such as “coercive” or “power differential.” Qualitative analysis software, NVivo 10, was used to search interview text. Sections where the keywords were found were exported from NVivo and assessed for relevance. Relevance was determined through a review of the context in all instances where keywords were used by interviewees. The paragraph containing the keyword was read and, if there was ambiguity as to whether the quote was relevant, surrounding paragraphs were examined. Excerpts relating to power differentials were sorted into tentative categories based on common perspectives or framing and themes within each perspective. Overarching themes were subsequently presented to the same group of subject-matter experts that reviewed the original list of keywords. These themes were reviewed to confirm the interpretations and thematic groupings.

Table 2. Power Relationships Keywords.

| Pressure |

|---|

|

Results

Nvivo identified 45 text excerpts relevant to power differentials. Of the 64 total participants, 27 participants returned no hits, 30 returned one hit, six returned two hits, and one returned three hits. These 45 excerpts were arranged into three general types of framing, which were further classified into subcategories. The three frames and seven subcategories can be viewed in Table 3. It was possible for participants to speak from multiple frames of reference (e.g., talk about power differentials from perspective of subordinate in one situation and as an authority figure in another) in their interviews, though this was rare and only occurred in a couple of cases.

Table 3. Text Findings.

| Frame 1: Authority Framing (10 participants total) |

|

| Frame 2: Subordinate Framing (28 participants total) |

|

| Frame 3: Peer Framing (7 participants) |

|

When discussing ethical dilemmas involving power differentials, each participant implicitly took a specific view of the situation as either a superior, peer, or subordinate. That is, interviewees would not say that they were going to discuss a topic as if they were a subordinate, but it could be understood from their explanations. These implicit frames of reference influenced the ways in which power differentials were discussed. Although several themes were identified, they were embedded in the perspectives from which participants viewed the situation. As such, themes were grouped according to the three possible frames of reference they could take in a situation. Passages used to illustrate the themes were rendered as paraphrases to protect participant identify (i.e., there are no direct quotes of participants in this article), while accurately reflecting the thoughts and tone of the interviewees.

Authority Framing

Some participants responded to these questions from an authority-figure perspective. One view expressed by these participants in the context of ethical scenarios involving power differentials is that authority places an obligation on the person in charge. Positions of power are viewed as a responsibility and often discussed in the context of protecting or mentoring subordinates. In addition to whatever other responsibilities they may have, those with authority must constantly be thinking about their subordinates. The relationship that a person in power has with a subordinate is viewed as especially important in ethical situations because people using this perspective believe that their positions give them an ethical responsibility to protect those with less power. This protective view can be seen in remarks such as, “We have a responsibility as educators and mentors to help them make good decisions. We can't make the decisions for them, but we can help them make informed choices” or “When I started my career, I didn't realize how much influence an advisor has on their graduate students. I was lucky that I had such a good mentor but oftentimes people don't realize if somebody is taking advantage of them [graduate students].” These paraphrases demonstrate an understanding that authority figures have both significant power over subordinate and insight and wisdom that the subordinate may not possess.

The second view is more authoritarian, that is, authority gives us power over people. In this view, authority is a reward for building up expertise and experience in a field. Responsibility will gradually be increased over the course of a successful career, and individuals over whom one has power exist to help one's career. The following paraphrase illustrates this view of power: “I'm in charge in this situation, so basically I can say, this is my decision, and this is the way that it is going to be. And my decision is final. You can complain about it, but ultimately, I'm the boss.” Another illustrative remark would be, “We are in a position where we have control over the careers of other people. And it's a powerful position. And if we don't like somebody, it can be detrimental to someone's career.” Like participants exhibiting the perspective that authority is a responsibility, participants with the more authoritarian view recognize that they have significant power over subordinates. Where they differ is in their view of power. The authoritarian view sees power as having control and the final word over the careers of subordinates.

Subordinate Framing

In the subordinate framing, participants took the perspective of a subordinate figure. The first common theme was to defer to existing channels to deal with abuse and violations of policy. In this framing, abuse and violations of policy would originate with those in positions of power over the participant. People expressing this opinion would say something like, “You need to remove yourself from such [ethically loaded] situations as quickly as possible. I would just report it to my department chair and let him deal with it. Explain the situation and hopefully he can take care of it” or “The solution is to take the problem to somebody in a position of authority. Report it [ethical misconduct] to the IRB. The important thing is to report it to the appropriate authority.” The underlying thinking across this theme was to remove oneself from the situation as quickly as possible, often passing responsibility to people in positions to deal with the situation, that is, other people with legitimate power relevant to the ethical situation at hand. There would be recognition of an ethical dilemma, as well as an understanding that although one may not personally be in a position to deal with an abuse of power, they should report it to somebody that could.

The second theme was to, as a subordinate, submit to authority. This method for dealing with ethical dilemmas involving power differentials basically related to keeping one's head down if one receives pressure to do something unethical. These excerpts are representative: “The cost of angering my advisor would be too great. If what he was asking was not too bad I would probably just go through with it. I mean, it's important that he trusts me and I would not want to jeopardize that over little disputes” or “If a higher-up was pressuring me to change a grade for a student or something I would just do it. Honestly, it's just not a battle worth fighting. There's probably a good reason they're asking me to do it and it's not like it costs me anything.” This rather cynical, or perhaps pragmatic, view of power differentials suggests that some individuals are consciously aware of the fact that they will submit to performing unethical behaviors if it protects their self-interests. This finding is potentially of great importance because it suggests a bias toward maintaining the status quo or perhaps an overly pragmatic method of solving ethical dilemmas. Rather than seeing abuses of power as something to be confronted, this perspective suggests that some people are consciously aware of the fact that they would turn a blind eye to ethical breaches in the workplace.

The distinction between somebody submitting to authority and one deferring to existing channels is potentially subtle. It could be argued that deferring to existing channels is another form of submitting to authority. Both framings are an attempt to deal with a conflict in which power differentials are an issue, but the way of addressing the issue appears to be quite different. In the submitting to authority framing, an individual submits to the authority figure that is causing the problem. Deferring to existing channels, on the other hand, often entails contacting an authority figure or institution outside of the current situation, almost as if to recruiting another authority to help address the issue.

The third theme was that of resisting power and standing your ground. This theme is the opposite of the second theme of submitting to authority. A person espousing this view might say something like, “I would never put my career in front of my values. I don't think everybody feels this way, but in general even if somebody has power over me I'll still do what I believe is right, even if it might hurt me” or “Sometimes you just have to do what you think is right. It might anger some people when you do it, but most of them will respect you for it in the future. You will find yourself placed in fewer compromising situations in the future when you stand your ground. If you compromise your beliefs people will walk all over you.” This perspective is almost the opposite of those who would simply submit to authority. Somebody taking this perspective believes that they would actively stand up against somebody if they recognized somebody abusing their power.

The fourth and final theme emerging under the subordinate framing was recognizing complexity in power relationships. This view of power differentials is something of a middle ground between submitting to power and standing your ground. Remarks along these lines are, “You could just go and report the behavior, but this would be damaging to a lot of people. I would probably sit down and have a talk with a few people and see if we can work things out. There are official channels but those are something of a last resort. If I can solve the issue without drawing attention to it, I think that's a preferable outcome” or “Sometimes you see things that you don't personally agree with, but you have to weigh the cost of taking action along with the risk of not doing anything. I hate to say it, but from a career standpoint, there is some value in overlooking some minor infractions.” This perspective emphasizes a sort of contingency approach for which the response must be in accordance with the ethical dilemma.

Overall, those discussing ethical dilemmas from the perspective of a subordinate viewing an abusive authority figure had the most different perspectives with regard to how to manage the situation as compared to the other two types of framing. The diversity of opinions may reflect a lack of consensus for how to view power differentials. This finding may be indicative of a lack of understanding for how best to proceed in ethical situations. Although there may be guidelines or training that exist to help educate or inform people of the proper methods and approaches, the point remains that academics have a wide range of views on how best to proceed in such situations. This could also potentially reflect differences in prior exposure to, and dealing with, unethical behavior and individual differences influencing perception (e.g., moral sensitivity).

Peer Framing

One theme emerged when the interviewee took the perspective of a peer: living with peers in spite of their perceived flaws. Participants who took the perspective of a peer primarily noted difficulties in bringing up ethical issues when they noticed peers engaging in unethical behavior. Sample remarks to illustrate this theme are as follows: “Most of these situations appear to be between a graduate student and a faculty member, but what about when you're a faculty member and you see other faculty doing fraudulent things? It goes on a lot, and even if there isn't a power differential between the two faculty, it's still not easy to report” or “I see power differentials all the time in my career. Faculty ask their graduate students to volunteer for lots of things they would not otherwise do. What is the student supposed to do? It's a common problem but I don't think it's something we like to talk about.” Being a peer to somebody committing an ethical violation is a notable perspective because one may be more likely to have the expertise and knowledge to recognize when an abuse is occurring. People with this perspective understand that power differentials are at the root of some problems but mostly would rather avoid addressing the issue when it does not directly involve them. That is, they will stay out of an ethically loaded situation when it does not explicitly concern them. This perspective is perhaps a common view but not the most beneficial for maintaining high ethical standards in a large institution.

Discussion

Implications

Academics have many different views and perspectives on power relationships. Regarding our research question, there are several key findings in the present study. First, participants were able to recognize that power differentials can result in power abuses in ethical situations. Regardless of the perspective taken, participants often expressed an internal tension regarding how to handle these problems. The power of academics comes from many sources; for example, they are often experts in their field, that is, they have expert power. Their positions give them power over both undergraduate and graduate students, so they have legitimate power. Through committees, they often have some limited influence over their peers, especially younger peers, through reward power, and many successful academics have some referent power that can help them in collaborations with other academics. With so many potential sources of power it should be clear that who has power in a given situation can often be a gray area among academics.

A second notable finding is that power differentials operate differently depending on how one frames power relationships. Discussions of power differentials in this sample took three perspectives: the senior person in a power hierarchy, the junior person in a power hierarchy, and a peer. Power differentials are viewed as more of a concern from the view of a subordinate as compared to the person with power. This finding is perhaps best illustrated by participants taking the perspective of a peer to somebody with power—that is, people tend to trust themselves with power, but they do not as easily trust other people.

There appears to be a lot of diversity in perceptions of how subordinates should handle these situations. When there is conflict in a power hierarchy, how should situations be resolved? Should people defer to existing channels? Stand up for what they think is right? Submit to power? These different options are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but they may bring about different outcomes for individuals and institutions. The diversity of responses to this issue may reflect some type of contingency approach. That is, different actions may be appropriate or successful in any given situation. People are likely to behave in ways that have been successful in the past; thus, different frames of reference may simply reflect historical strategies that have previously proven beneficial. Regardless of this fact, the ambiguity of many ethically loaded situations presents challenges to people in situations involving power differentials.

Although people often trust themselves to be ethical in situations in which they have power, they are less trusting of their peers. People may be suffering from the illusory superiority bias (Hoorens, 1995). People have an inflated view of their projected selves (Brown, 2005). They believe they would act ethically in a hypothetical situation while being more pessimistic about how their peers may behave. No participants expressed a fear that they were abusing their power, though it was very common for participants to make the point that they had seen abuses of power throughout their careers (i.e., while they were earlier in their careers as well as to the present day), a finding consistent with attribution theory (Kelley, 1967). People may have been making internal attributions when thinking about the behavior of others while not acknowledging the role of external influences. The point that participants believed themselves to be above reproach on ethical issues may reflect a sort of impression management on the part of participants, that is, they may not want to detail any misconduct of their own in an interview. A more plausible explanation is that our participants believe themselves to be above average at making ethical decisions.

Those in positions of authority may not be fully aware of how power differentials and potential abuses are viewed by subordinates. Also, subordinates may not know how to handle ethical dilemmas involving those with more power than themselves, in part because they don't always grasp the complexities of power relationships in ethical situations. Both of these potential issues can be addressed through integration of discussion of power perceptions and potential abuses and how to deal with them into formal and informal training. From the perspective of formal training, ethics training programs may benefit from sections dedicated to explaining the influences of authority figures and power differentials and how they constrain effective ethical decision making. Gunsalus (1998) gave similar advice, recommending that orientation programs be implemented to help make people aware of the power they may wield. He also made the point that formal processes become more important as the power differential involved in a situation is increased (e.g., an undergraduate raising concerns about a star faculty member). This type of intervention focusing on power differentials could be implemented through training on the types of protection and resources available to people reporting ethical breaches or even information gathering techniques focused on helping people more fully understand all aspects of a situation.

Informally, we should not solely rely on mentors to pass on this information, but it could potentially be integrated into the professional norms and standards in a discipline. Most disciplines already have codes of conduct and ethical guidelines (Center for Business Ethics, 1992), so it is not a large step to say that these could address issues relating to power differentials beyond the specific domains of sexual harassment and bullying in the workplace, both of which may already address power differentials to some degree.

Limitations and Future Research

A number of limitations should be noted. First, there may have been response biases in the types of thoughts and stories participants were willing to share. It is possible that interviewees felt pressure to respond in a way that portrayed themselves in a positive manner, though this limitation did not seem evident. Many participants expressed rather open or blunt perspectives on power differentials. Second, participants' discussions may have been constrained by the use of preexisting scenarios, that is, discussions may not have been fully representative of their own personal experiences with power abuses in academia. We believe this limitation to not be a significant problem, because the scenarios often led to deeper discussions of personal experiences similar to the scenarios. Along these lines, limitations should be noted in that 27 participants did not discuss anything that related to power differentials. The scenarios may have been too subtle if so much of the sample did not find it relevant to discuss power differentials. Another limitation is that this study does not shed light on which power perspectives and themes are more ethical than others. Answering this question requires more empirical research.

Although the present study may provide some better understanding of the types of ways academics understand power relationships in ethical decision situations, more work needs to be done in this area. One potential area would be to use alternative methods to examine the same issue. Whereas think-aloud protocols may provide rich and descriptive information about what academics think about the issue, they do not necessarily provide information regarding the prevalence of each theme. Also, this method is inherently retrospective and can describe only what is, not what should be. Thus, future research could seek to answer the question of what type of thinking regarding power could be more effective in coming to good ethical decisions. Last, efforts should be made to more explicitly understand how the different bases of power (French & Raven, 1959) influence ethical decision making. For example, does the specific source of power a leader uses most often influence the likelihood of a subordinate to report unethical behavior? How should an individual go about understanding whether a leader relying on expert power is behaving ethically?

Conclusions

The goal of the present effort was to gain a better understanding of how academics view power differentials in ethical situations. Using qualitative analysis, several important themes were identified that provide initial evidence for the differing views on this complicated relationship. Notably, views on this topic are surprisingly diverse. This reflects the complicated nature of power perceptions and suggests that there may be a need for more professional discussion and training to better understand the impact of power differentials in ethical situations. In addition, future research is needed to better understand causal relationships of power perceptions to actual ethical behavior.

Acknowledgments

Parts of this work were sponsored by Grant No. R21 ES021075-01 from the National Institutes of Health. We thank T. H. Lee Williams for his contributions to this effort.

References

- Antes AL, Brown RP, Murphy ST, Waples EP, Mumford MD, Connelly S, Devenport LD. Personality and ethical decision-making in research: The role of perceptions of self and others. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics: An International Journal. 2007;2:15–34. doi: 10.1525/jer.2007.2.4.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RP. Ethical decision study. University of Oklahoma; Norman: 2005. Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- Burger JM. Replicating Milgram. American Psychologist. 2009;64:1–11. doi: 10.1037/a0010932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Business Ethics. Instilling ethical values in large corporations. The Journal of Business Ethics. 1992;11:863–867. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Gender and power: Society, the person, and sexual politics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland JT. Prophecies of power: Motivational implications of social power for behavioral confirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:264–277. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl R. The concept of power. Behavioral Science. 1957;2:201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar NE, Burgoon JK. Perceptions of power and interactional dominance in interpersonal relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22:207–233. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding NG, Lee RM. Computer analysis and qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. Mew York, NY: Pantheon; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- French JRP, Raven B. The base of social power. In: Cartwright D, editor. Studies in social power. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 1959. pp. 150–167. [Google Scholar]

- Gaski JF, Nevin JR. The differential effects of exercised and unexercised power sources in a marketing channel. Journal of Marketing Research. 1985;22:130–142. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman S, Gibelman M. Plagiarism in academia: Are students emulating (bad) faculty role models?. 2002, November; Paper presented at the second research conference on research integrity of the Office of Research Integrity; Potomac, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Gerth HH, Mills CW. From Max Weber: Essays in sociology. London, UK: Routledge; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SA, Gubin A, Fiske ST, Yzerbyt VY. Power can bias impression processes: Stereotyping subordinates by default and by design. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. 2000;3:227–256. [Google Scholar]

- Gunsalus CK. Preventing the need for whistleblowing: Practical advice for university administrators. Science and Engineering Ethics. 1998;4:75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Haney C, Banks WC, Zimbardo PG. A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Review. 1973;30:4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson R, Roscigno VJ, Lopez SH. Chaos and the abuse of power: Workplace bullying in organizational and interactional context. Work and Occupations. 2006;33:382–416. [Google Scholar]

- Hoorens V. Self-favoring biases, self-presentation, and the self-other asymmetry in social comparison. Journal of Personality. 1995;4:793–817. [Google Scholar]

- Indvik J, Johnson P. Liar! Liar! Your pants are on fire: Deceptive communication in the workplace. Journal of Organizational Culture, Communication and Conflict. 2009;13:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby S. Employing bureaucracy: Managers, unions, and the transformation of work in the 20th century. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jermier JM, Knights D, Nord W. Resistance and power in organizations. London, UK: Routledge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH. Attribution theory in social psychology. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. 1967;15:192–238. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey LLM, Dunbar NE, Russell J. Risky business or managed event? Power and deception in the workplace. Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications, and Conflict. 2011;15:55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lively KJ. Client contact and emotional labor: Upsetting the balance and evening the field. Work and Occupations. 2002;29:198–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mann M. The autonomous power of the state: Its origins, mechanisms and results. European Journal of Sociology. 1984;25:185–213. [Google Scholar]

- Marx K. Capital, volume one. In: Tucker RC, editor. The Marx-Engels Reader. 2nd. New York, NY: Norton; 1978. pp. 294–438. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram S. Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1963;67:371–378. doi: 10.1037/h0040525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg DJ, Velasquez M. The ethics of mentoring. Business Ethics Quarterly. 2004;14:95–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford MD. Pathways to outstanding leadership: A comparative analysis of charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leadership. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford MD, Devenport LD, Brown RP, Connelly S, Murphy ST, Hill JH, Antes AL. Validation of ethical decision making measures: Evidence for a new set of measures. Ethics & Behavior. 2006;16:319–345. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K. Judge throws out conviction in Enron case. The New York Times. 2007 Feb 31; Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/

- Olson M. Power and prosperity: Outgrowing communist and capitalist dictatorships. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Oyamot CM, Fuglestad PT, Snyder M. Balance of power and influence in relationships: The role of self-monitoring. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2010;27:23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Priestland D. Merchant, soldier, sage: A new history of power. London, UK: Allen Lane; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roloff ME, Cloven DH. The chilling effect in interpersonal relationships: The reluctance to speak one's mind. In: Cahn DD, editor. Intimates in conflict: A communication perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev I, Bourhis RY. Social categorization and power differentials in group relations. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1985;15:415–434. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev I, Bourhis RY. Power and status differentials in minority and majority group relations. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1991;21:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Skarlicki DP, Folger R. Retaliation in the workplace: The roles of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1997;82:434–443. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl G. Leadership in organizations. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zinn H. A people's history of the United States: 1492 to present. New York, NY: Harper Perennial; 2005. [Google Scholar]