Abstract

Adolescents exposed to interparental aggression are at increased risk for developing adjustment problems. The present study explored intervening variables in these pathways in a community sample that included 266 adolescents between 12 and 16 years old (M = 13.82; 52.5% boys, 47.5% girls). A moderated mediation model examined the moderating role of adrenocortical reactivity on the meditational capacity of their emotional insecurity in this context. Information from multiple reporters and adolescents’ adrenocortical response to conflict were obtained during laboratory sessions attended by mothers, fathers and their adolescent child. A direct relationship was found between marital aggression and adolescents’ internalizing behavior problems. Adolescents’ emotional insecurity mediated the relationship between marital aggression and adolescents’ depression and anxiety. Adrenocortical reactivity moderated the pathway between emotional insecurity and adolescent adjustment. The implications for further understanding the psychological and physiological effects of adolescents’ exposure to interparental aggression and violence are discussed.

Keywords: interparental aggression, adolescent adjustment, emotional insecurity, cortisol

Intimate partner violence is a societal problem with physical, emotional and economic costs for victims, perpetrators and witnesses (Perkins & Graham-Bermann, 2012; Howell, 2011; Levendosky & Graham-Bermann, 2001). Furthermore, these problems have implications for adolescents in their immediate family context, who may be impacted by these behaviors and carry the ramifications of their influence with them throughout their lives. Adolescents who are exposed to martial aggression are also at risk for internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (Evans, Davies, & DiLillo, 2008). Interparental aggression and violence is a salient threat for far too many families. Alarmingly, previous research may have dramatically underestimated the frequency of children’s and adolescents’ exposure to interparental aggression and violence. Although a common assumption has been that approximately 1 in every 8 American families experienced some form of aggression between parents, estimates as staggeringly high as 49% are reported more recently (Klostermann & Fals-Stewart, 2006; Smith Slep & O’Leary, 2005). The focus has been on fathers as perpetrators of violence. A growing body of research, however, illuminates the role of mothers as perpetrators of violence at a rate as high as or slightly higher than for men (Klostermann & Fals-Stewart, 2006; Fergusson & Horwood, 1998). Violent acts committed by mothers against fathers are also upsetting to children (Goeke-Morey, Cummings, Harold & Shelton, 2003), although the consequences of male-to-female aggression may be more severe (Klostermann & Fals-Stewart, 2006, Fergusson & Horwood, 1998). A similar impact on children of male-to-female and female-to-male aggression is reported in some recent studies (El-Sheikh, Cummings, Kouros, Elmore-Staton, & Buckhalt, 2008). Furthermore, studies of exposure to marital aggression and child adjustment support the notion that aggression against either parent threatens children’s emotional security (El-Sheikh, et al., 2008). Emotional insecurity resulting from exposure to marital aggression predicts increases in internalizing and externalizing problems over time (Cummings, Schermerhorn, Davies, Goeke-Morey & Cummings, 2006).

Links between destructive marital conflict and adolescent adjustment are well-established (Davies & Cummings, 1998; Kerig, 1998; Porter & O’Leary, 1980). Studies have shown associations between exposure to destructive marital conflict (e.g. hostility, stonewalling, threatening) and both internalizing and externalizing problems in children and adolescents. Having documented the relationship between marital conflict and adjustment, the focus of research is on the mechanisms through which marital discord affects children (Cummings & Davies, 2010).

Interparental aggression and violence (e.g. hitting, shoving, throwing objects) can be thought of as extreme instances of marital conflict (Moffitt and Caspi, 1998). Children of parents who engage in physically aggressive acts against each other are at increased risk for developing various forms of psychopathologies in relations to their peers who are not exposed to these behaviors (McDonald and Jouriles, 1991). Furthermore, exposing one’s child to physical aggression and violence between parents has been described as a form of psychological maltreatment (Margolin & Gordis, 2000). As such, adolescents’ exposure to aggression and violence during conflicts between their parents produces an environment of risk associated with negative ramifications for adolescents’ adjustment, including internalizing (e.g. anxiety, depression) and externalizing (e.g. delinquency, aggression) behavior problems (El-Sheikh, et al, 2008). In their meta-analysis of the relationships between exposure to interparental violence and adjustment, Evans, Davies and DiLillo (2008) reported moderate effects of exposure to domestic violence on internalizing and externalizing symptoms and large effects on trauma symptoms.

Although negative outcomes are the focus of research, the range of adjustment problems varies widely; some children exposed to intimate partner violence do not display any kind of psychopathology (Hughes & Graham-Bermann, 1999). The developmental psychopathology perspective highlights the need to understand the mechanisms through which associations between risk factors and outcomes occur, including for whom and when, and why and how, these risk factors are linked with children’s adjustment problems (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000). Furthermore, working within this framework, Rutter and Sroufe (2000) emphasized the need to understand protective mechanisms that can account for adaptive functioning in the face of extreme risk, like that presented by exposure in interparental aggression (Martinez-Torteya, Bogat, von Eye & Levendosky, 2009).

The emotional security theory (EST, Davies & Cummings, 1994) may explain risk and protective mechanisms, providing a cogent theoretical framework for understanding the links between risky developmental contexts and adolescent adjustment. EST describes a primary goal of children as the preservation of security in the family; this goal motivates their actions and organizes their emotional and physiological responses, behaviors, and appraisals of themselves and others when that security is threatened. When their security is threatened by dysfunction in family processes, children may become vigilant, worried, distressed and more negative in their appraisals of people and situations, increasing vulnerability for the development of internalizing and externalizing problems. On the other hand, when emotional security remains intact, it serves a protective function against the negative effects of deficits in family functioning, supporting children’s capacity to cope with threatening situations. Emotional insecurity, then, mediates the effects of exposure to marital aggression on adjustment by shaping adolescents’ emotional, behavioral and cognitive reactions to it. As such, this theory predicts that emotionally secure adolescents will display fewer indicators of adjustment problems, even after having been exposed to destructive forms of conflict, whereas adolescents’ emotional insecurity may manifest in dysregulated emotions or behaviors, hostile representations of the family and overregulation of their exposure to marital conflict as they attempt to regain a sense of security (Cummings & Davies, 2010).

Despite the potential for negative developmental ramifications of exposure to environments characterized by interparental aggression and violence, the risk for adjustment problems is probabilistic, not certain; varying degrees of subsequent maladjustment and adaptive functioning are found among children and adolescents (Hughes & Graham-Bermann, 1999), underscoring the importance of identifying and understanding intervening constructs that may diminish or exacerbate these effects. The present study explores the processes through which maladaptive development occurs in these contexts of family adversity, that is, how interparental aggression predicts differences in adolescents’ adjustment. Specifically, the mediating role of emotional insecurity and the moderating role of adolescents’ adrenocortical activity are examined.

Davies, Winter and Cicchetti (2006) describe a theoretical explanation for the potential mediating role of emotional insecurity in instances of exposure to extreme adversity in the family context. Concerns about family security and the emotional and behavioral reactions to exposure to marital aggression that accompany those concerns may be adaptive in the short-run. In the long-run, however, these reactions may put children and adolescents at risk for developmental maladjustment. First, children exposed to marital violence may apply their interpretation of those experiences to other social situations, like interactions with peers, causing them to develop inaccurate expectations about the course and consequences of social interactions. Secondly, constant threats to adolescents’ security as a result of exposure to interparental violence may deplete adolescents’ coping resources, disrupting their physiological and neuropsychological systems. Thirdly, by diminishing their coping resources, emotional insecurity may make it difficult for adolescents to respond to stage-salient challenges they encounter, laying the groundwork for subsequent maladjustment. The present study seeks to empirically test theoretical assertions that emotional insecurity is a threat for adolescents’ adjustment when it occurs as a result of marital aggression.

Physiological reactivity has been shown to function as a vulnerability factor for adjustment problems when it interacts with other aspects of their environment. In particular, studies have indicated a link between adrenocortical activity and children’s reactivity to interparental conflict (Davies, Sturge-Apple, Cicchetti, & Cummings, 2008), and support has emerged for the moderating role of stress reactivity in the relationship between family adversity and children’s socioemotional and cognitive outcomes (Obradovic, Bush, Stamperdahl, Adler, & Boyce, 2010). Adrenocortical reactivity, commonly indicated by changes in cortisol, refers to a physiological stress response associated with activity in the limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (LHPA) system. A normal response to an acute stressor includes heightened cortisol concentrations several minutes after the stressful event, followed by an eventual return to baseline levels. Releasing cortisol in response to stress can be protective, but abnormally high and low cortisol responses have been linked to various indices of adjustment problems, including internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Chronic stress, like exposure to interparental aggression, has been shown to be particularly impactful on diurnal patterns (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2007), but over time variations in the diurnal rhythm because of chronic exposure to stress can also influence the pattern of the more immediate adrenocortical response to an acute stressor.

Links between adrenocortical reactivity and one’s ability to regulate the negative emotions elicited by psychologically stressful situations are reported (Stansbury & Gunnar, 1994). Emotional reactivity is an important component of emotional security, so it follows that deficits in physiological processes linked to adolescents’ abilities to regulate negative emotional responses could impact the magnitude of the relationship between their emotional security and behavior. The present study extends directions in the exploration of the role of physiological reactivity in children’s coping with marital conflict and aggression by including a test of moderated mediation, consistent with other evidence in the literature (Cummings, El-Sheikh, Kouros & Keller, 2007), adolescents’ adrenocortical activity was expected to function as a vulnerability factor, moderating the effect of adolescents’ emotional insecurity on their adjustment.

The Present Study

Marital aggression impacts adolescent adjustment (McDonald & Jouriles, 1991; El-Sheikh & Flanagan, 2001). The mediating role of emotional insecurity is supported, with emerging evidence for the moderating role of adrenocorticol responding (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Obradovic, et al., 2010). Despite the links between each of these various constructs, however, relatively few studies have examined the combined influence of these specific risk and protective factors on adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors. The present study addresses this gap in three important ways. First, adolescents’ emotional insecurity was examined as an intervening variable in the path from interparental aggression to adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. It was hypothesized that aggression would impact adolescents’ adjustment, manifested in internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, through its effect on adolescents’ emotional security. That is, emotional insecurity was expected to mediate the relationship between interparental aggression and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. Second, a test of moderated mediation compared the impact of adrenocortical reactivity on the effect of adolescents’ emotional insecurity on their adjustment outcomes. It was hypothesized that adrenocortical reactivity would moderate the effect of adolescents’ emotional insecurity on their adjustment, such that emotional insecurity would have a greater effect on behavior for adolescents with heightened physiological responding to exposure to family conflict. That is, a conditional indirect effects model was proposed, advancing that the effect of interparental aggression on adolescents’ adjustment occurs via their emotional insecurity and depends on their level of adrenocortical activity. Finally, in each of these analyses, the effects of both mothers’ and fathers’ marital aggression are included, in contrast to a tendency in the literature to focus on the impact of only one parent (usually fathers).

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited as part of a larger, multisite study on family functioning and development. In mid-sized Midwestern and Northeastern cities, community families were recruited to participate.

Representative of the communities from which they were drawn, participants included 266 adolescents and their mother and father or primary adult caregivers. Adolescents ranged in age from 12–16 years (M=13.82, SD=0.697). Adolescents were approximately evenly split by gender (47.5% female). The median grade level for adolescents at the time of data collection was eighth. The majority of the sample identified themselves as European American (79.6%), fewer identified themselves as African-American (14.6%), Hispanic (3.8%), Multi-racial (2.3%), American Indian or Alaskan Native (1.5%), Asian-American (1.2%), or Other (0.8%). Median family income fell in a range between $55,000 and $74,999, but families reported yearly incomes in ranges as low as $6000 or less (5 families) and as high as $125,000 or more (26 families). The majority of couples were married (83.5%), with significantly fewer reporting that they were either cohabitating (13 families), single (7 families), divorced (14 families), separated (10 families) or widowed (4 families).

Fathers ranged in age from 23 to 77 years old (M=44.64, SD=6.94). The majority of fathers (80%) were the biological parent to their child. Twenty-seven step-fathers were also included in the sample, as were eight adoptive fathers, four live-in boyfriends, three legal guardians, two grandfathers and one uncle. The majority of fathers in the samples had completed at least some college (72.1%), although their educational experience ranged from completing 7th grade (one participant) to obtaining a doctoral degree (12 participants). The majority of fathers (80.9%) reported working full time.

Mothers ranged in age from 26 to 73 years old (M=43.14, SD=5.96). The majority of mothers (93.4%) were the biological parent to their child. Also included in the sample were six adoptive mothers, four grandmothers, three step-mothers, two legal guardians, one live-in girlfriend and 1 aunt. The majority of mothers in the samples had also completed at least some college (69.7%), but again they had a wide range of educational experiences from completing 6th grade (one participant) to obtaining a doctoral degree (three participants). Approximately half of the mothers in the sample (49.6%) reported working full-time.

Procedure

Once annually, mothers, fathers and adolescents participated in a laboratory visit as a family. Additionally, mothers and their adolescent child participated in a second laboratory visit each year. Each visit lasted approximately three hours. During each visit, participants completed electronic questionnaires independently which asked questions about marital conflict, interparental aggression and adolescents’ emotional security and adjustment. Families were compensated monetarily at the end of each laboratory visit. Adolescents also received compensation in the form of a gift card of their choice.

Measures

Interparental aggression

Both parents reported on incidents of aggression and violence in their relationship on the Conflicts and Problem-solving Scale (CPS; Kerig, 1996). On this scale, they had the opportunity to report on their own use of physical aggression against their partner, and also on their partner’s use of physical aggression against them. The CPS has six subscales that address various aspects of conflicts between partners. Interparental aggression and violence was measured using the Physical Aggression sub-scale of the CPS. This scale contains seven items that describe different forms of physical aggression that might be used during conflicts (e.g. “slap partner” and “strike, kick, bite partner”), and participants rate the frequency with which they and their partner use each strategy during conflicts on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from “0” meaning “never” to “3” meaning “often”. As such, scores on the physical aggression subscale of the CPS can range from 0 – 21, and items are summed so that high scores represent greater use of aggression. The CPS has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Kerig, 1996). In this sample, alpha reliabilities for mothers’ reports of their own use of physical aggression against their partners and for their partners’ use of physical aggression against them were good (Cronbach’s alpha = .76 and Cronbach’s alpha = .84, respectively). Alpha reliabilities for fathers’ reports of their own use of physical aggression against their partners and for their partners’ use of physical aggression against them were also good (Cronbach’s alpha = .78 and Cronbach’s alpha = .84, respectively).

Adolescent Emotional Insecurity

Adolescents’ emotional insecurity was measured by self-reports on the Security in the Interparental Subsystem questionnaire (SIS; Davies, Forman, Rasi & Stevens, 2002). The SIS examines emotional security processes though adolescents’ responses to 50 items about their reactions to witnessing disagreements between their parents. On the SIS, adolescents described how true statements were about them on a scale ranging from “1” meaning “not at all true of me” to “4” meaning “very true of me”. The statements described reactions to witnessing conflicts that fall into three categories: emotional reactivity (“I feel scared” and “I yell at or say unkind things to people in my family”), behavioral dysregulation (“I try to get away from them” and “I try to solve the problem for them”), and Destructive Internal Representations (“I worry about my family’s future”). The subscales can be combined to indicate an overall level of emotional insecurity, such that higher scores on the SIS correspond with increased emotional insecurity. This composite measure was used for the present analyses. The psychometric properties of the SIS are good (Davies, et al., 2002). Reliability for the composite measure was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = .94).

Adrenocortical Reactivity

Salivary cortisol was collected in the late afternoon and early evening to reduce the impact of the diurnal pattern of cortisol productions. Adolescents provided their samples using a passive drool technique before and after they were involved in a conflict between family members (for details on the method for the collection of cortisol, see Granger et al., 2007). In an effort to elicit a stress response from the adolescents that was similar to one they may have experienced at home, saliva collections were timed around a conflict task during which all three family members were asked to discuss for seven minutes a topic that was typically difficult or hard to handle in their relationship, in a manner that they normally would at home. A baseline cortisol sample was collected prior to the task, and three samples were collected in 10-minute increments following the task. The first of the three post-conflict saliva collections occurred approximately 10 minutes after the peak of the conflict. Adolescents’ pre- and post-conflict saliva samples were analyzed for cortisol concentrations by Salimetrics Inc. (State College, PA), using a highly sensitive immounassay. Samples were tested in duplicate form using 25 µl of saliva. The test sensitivity ranged from .007 µg/dl to 3.0 µg/dl. Based on these test results, baseline levels were subtracted from the first post-conflict assessment to represent reactivity.

Adolescent Adjustment

Adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behavior problems were assessed through both parents’ reports on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). The CBCL includes 56 statements for which parents rate how true each item is about their child on a scale ranging from “0” meaning “not true (as far as you know)” to “2” meaning “very true or often true”. Scores for the internalizing behavior problems include parents’ responses about their children’s withdrawal (e.g. “would rather be alone than with others”) and anxious/depressed (e.g. “worries” and “cries a lot”) behaviors and somatic complaints (e.g. “stomach aches or cramps”). Scores for externalizing behavior problems include parents’ responses to questions about their children’s aggressive (e.g. “physically attacks people”) and delinquent (e.g. “lying or cheating”) behaviors. Higher scores on the CBCL indicate more adjustment problems. The CBCL has excellent validity and reliability (Achenbach, 1991). Alpha reliabilities for this sample for mothers’ reports for internalizing and externalizing behaviors were good (Cronbach’s alpha = .85 and Cronbach’s alpha = .92, respectively). For fathers, respective alpha reliabilities were also good (Cronbach’s alpha = .84 and Cronbach’s alpha = .92).

Additional indicators of internalizing behavior problems included adolescents’ self-reports on the Revised Measure of Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds and Richmond, 1978) and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Adolescents (CES-D; Radloff, 1991). On the RCMAS, adolescents responded either “yes” or “no” about themselves to a series of 37 statements that described anxiety symptoms. Examples include “I worry a lot of the time” and “I get nervous when things do not go the right way for me”. The RCMAS contains a Lie Scale that checks for socially desirable responding. Answers to the lie scale were omitted, and remaining “yes” responses were summed to obtain a composite score so that higher scores represented more anxiety. Alpha reliability in this sample was good (Cronbach’s alpha = .87).

The CES-D contains 20 statements describing depressive symptoms about which adolescents described the frequency with which they had experienced each during the last week on a scale ranging from “0” meaning “less than a day” to “3” meaning “5–7 days”. Examples include statements like “I felt sad” and “I could not get going”. Scores were summed so that higher scores represented more depressive symptoms. Alpha reliability in this sample was good (Cronbach’s alpha = .86).

Results

Preliminary analyses included descriptive statistics of means and standard deviations in addition to correlations among the variables in the model. A series of one-way ANOVAs were also performed to test for differences between reporters, and correlations were performed on all study variables and several demographic variables to detect possible confounds related to SES, parental age, and level of education. Some significant patterns emerged from these correlations, but the strength of the relationships that were significant was consistently low. Specifically, mothers’ and fathers’ use of physical aggression was related to total family income (r = −.24 and −.26, p <.01), such that families with lower incomes tended to report greater use of physical aggression during conflicts. Significant correlations were similarly weak for family income and indices of adolescent adjustment (correlations ranged from −.18 to −.24, p < .01). Correlations were not significant between family income and alcohol use or children’s emotional insecurity. Additionally, fathers’ age was related to mothers’ use of physical aggression during conflict (r = −.18, p < .01), and parents’ level of education was related to indices of adolescent adjustment (significant correlations ranged from r = −.20 to −.14, p < .05). Although significant, the relationships were weak, confirming that the constructs of interest in this study were not marker variables for income level or parental age or education.

Correlations for continuous study variables are presented in Table I. With the exception of the correlation between mothers’ and fathers’ use of physical aggression (r = .68, p < .01), most significant correlations between study variables were low. Noteworthy among the patterns that emerged, adolescent self-reports of depression and anxiety were not highly correlated with parental reports of internalizing behavior problems (r = .09, n.s. and r = .18, p < .05). This speaks to the importance of including reports from multiple informants, particularly on measures of internalizing behaviors, as different measures may capture different manifestations of disorder. Also of note, fathers’ but not mothers’ use of physical aggression was positively related to adolescents’ emotional insecurity and anxiety. Both parents’ physical aggression was related to their reports of adolescents’ internalizing behaviors. [Insert Table I]

Table I.

Correlations of Key Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Physical aggression (mothers) | ---- | |||||||

| 2. Physical aggression (fathers) | .68** | ---- | ||||||

| 3. Physical aggression (overall) | .91** | .92** | ---- | |||||

| 4. Emotional insecurity (adolescent) | .10 | .24** | .19** | ---- | ||||

| 5. Adolescent internalizing (parent) | .22** | .24** | .25** | −.02 | ---- | |||

| 6. Adolescent externalizing (parent) | .08 | .11 | .10 | −.06 | .62** | ---- | ||

| 7. Adolescent depression (self-report) | −.01 | .07 | .04 | .31** | .05 | .06 | ---- | |

| 8. Adolescent anxiety (self-report) | .03 | .19** | .12 | .38** | .14* | .07 | .6** | ---- |

Notes:

p < .05,

p < .01

Means and standard deviations for interparental aggression are displayed in Table II. No significant differences between parents’ use of physical aggression were found (t (246) = −.183, p = .855). Scores on the CPS ranged from 0 – 16 for mothers and 0 – 20 for fathers. Reports on the CPS revealed the use of at least some physical aggression in 119 mothers (48.0%) and 112 fathers (45.3%). To assess the degree of adolescents’ overall exposure to interparental aggression, scores were created for each construct by summing reports for mothers and fathers; composite scores were used for subsequent analyses.

Table II.

Descriptive Statistics

| N | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Aggression (CPS; mothers) | 248 | 1.98 | 3.35 |

| Physical Aggression (CPS; fathers) | 247 | 2.02 | 3.54 |

| Emotional Insecurity (SIS; adolescents) | 244 | 90.12 | 22.09 |

| Internalizing (CBCL; adolescents) | 260 | 5.19 | 4.67 |

| Externalizing (CBCL; adoelscents) | 260 | 6.68 | 7.18 |

| Depression (CES-D; adolescents) | 254 | 30.40 | 8.65 |

| Anxiety (RCMAS; adolescents) | 253 | 8.34 | 5.85 |

Means and standard deviations for adolescents’ emotional insecurity and adjustment measures are displayed in Table II. Parents did not differ significantly in their reports of adolescents’ internalizing or externalizing behavior problems, (t (223) = 1.67, p = .097; t (223) = .291, p = .771, respectively); the average of mothers’ and fathers’ reports on the internalizing and externalizing scales was used in subsequent analyses. One hundred twenty-four adolescents (48.8%) reported scores on the CES-D at or above the clinical cut-off. Sixteen adolescents (6.3%) reported scores on the RCMAS that were at or above the clinical cut-off. [Insert Table II]

Preliminary analyses also established direct relationships between overall exposure to interparental aggression such that greater use of interparental aggression was significantly related to parental report of adolescents’ internalizing behavior problems (t (247) = 3.90, p < .001), and adolescents’ self-reports of anxiety (t (237) = 1.99, p = .048). Interparental aggression was not related to adolescents’ externalizing behaviors or depression.

Primary Analyses

Primary analyses were carried out in the SPSS statistical package. They included regression analyses to tests for direct effects, mediation, and moderated mediation, according to the guidelines set forth by Preacher and Hayes (2004), Preacher, Rucker and Hayes (2007), and Muller, Judd and Yzerbyt (2005). In the direct effects model, marital aggression impacts adolescent adjustment, such that higher levels of marital aggression were associated with greater adjustment problems. The mediation analyses empirically tested the supposition that emotional insecurity acts as a mechanism through which marital aggression effects adolescent adjustment, such that increased emotional insecurity is associated with higher levels of maladaptive behaviors in adolescents. The moderated mediation combines the mediator model with the added dimension of adolescents’ adrenocortical activity as an intervening variable such that adrenocortical reactivity affects the magnitude of the effect of emotional insecurity on adolescent adjustment. This model would suggest that the magnitude of the effect of interparental aggression on adolescents’ adjustment, which occurs through its effect on adolescents’ emotional security, depends on adolescents’ adrenocortical activity.

Hypothesis 1: Emotional Insecurity as Mediating Process

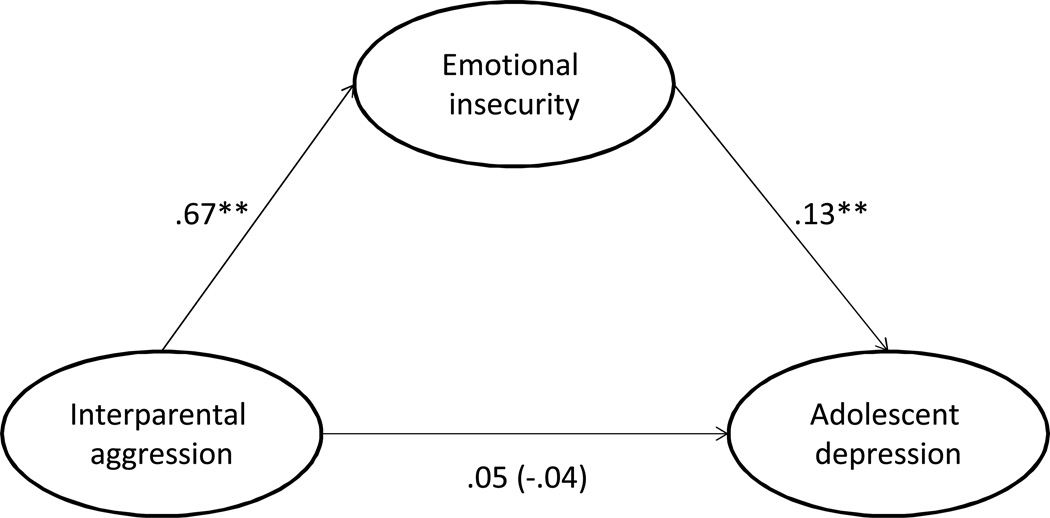

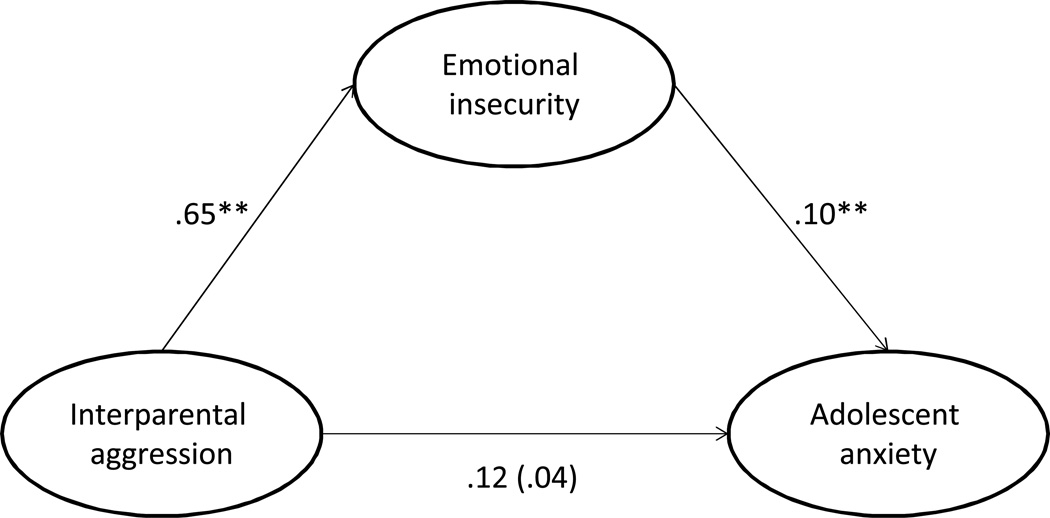

Tests of the mediating role of emotional insecurity in the relationships between exposure to marital aggression and adolescent adjustment were carried out according the recommendations of Preacher and Hayes (2004) using an SPSS macro they developed. Significant Sobel test statistics and non-zero confidence intervals generated by bootstrapping indicated significant mediation by a dolescents’ emotional insecurity in the relationship between exposure to interparental aggression and adolescent depression (z = 2.57, p = .01; 99% CI [.02, 21]), and anxiety (z = 2.59, p = .01; 99% CI [.02, .15]). Models of these relationships are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2 below. These results suggest that emotional insecurity is a mechanism through which exposure to marital aggression impacts adolescents’ adjustment. [Insert Figures 1 and 2]

Figure 1.

Unstandardized path coefficients for the relationship between interparental aggression and adolescent depression as mediated by emotional insecurity. The unstandardized coefficient for interparental aggression and adolescent depression controlling for emotional insecurity is in parentheses.

** p < .01.

Figure 2.

Unstandardized path coefficients for the relationship between interparental aggression and adolescent anxiety as mediated by emotional insecurity. The unstandardized regression coefficient for interparental aggression and adolescent anxiety controlling for emotional insecurity is in parentheses.

** p < .01.

Hypothesis 2: Moderated Mediation by Cortisol Responding

Moderated mediation occurs when the effect of the mediator on the outcome is moderated (Muller, et al., 2005). Analyses were carried out using an SPSS macro designed by Preacher, et al., (2007). Syntax was specified to use the multiplicative interaction term between emotional insecurity and cortisol reactivity in the b path of the standard mediation model. That is, interparental aggression was the predictor, mediated by emotional insecurity, and the effect of emotional insecurity on adolescent adjustment was moderated by their adrenocortical stress reactivity. Caution has been advised in interpreting significance tests that assume the normality of distributions for this kind of analysis (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). Because the sampling distribution of the conditional indirect effect is not normally distributed, a nonparametric approach, that is, bootstrapping, was used to confirm the conditional indirect effect. This approach has been increasingly advanced in the literature as a preferable alternative to normal-theory tests (Preacher, et al., 2007). Accordingly, bias corrected confidence intervals are reported for levels of the moderator that fall one standard deviation below the mean, at the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean. Supporting the second hypothesis, tests of the moderated mediation model revealed significant effects of adrenocortical reactivity in the relationship between emotional insecurity and adolescents’ adjustment, that is, bootstrapping procedures confirmed that in the context of the conditional indirect effects model for exposure to marital aggression, cortisol reactivity moderated the association between adolescents’ emotional insecurity and internalizing problems. For low levels of cortisol reactivity, bootstrapping with 5000 resamples yielded a 95% BCa CI of [.008, .116] for anxiety and [.012, 167] for depression. At intermediate levels of cortisol reactivity, 95% BCa CIs were [.009, .108] for anxiety and [.016, .156] for depression, and for high levels of cortisol reactivity 95% BCa CIs were [.008, .125] for anxiety and [.015, 166] for depression. Confidence intervals not containing zero indicate the significance of the conditional indirect effect, as such it can be concluded that the indirect effect of exposure to marital aggression on adolescents’ anxiety and depression through their emotional insecurity was conditional on their level of cortisol reactivity.

Discussion

The present study examined the mechanisms through which interparental aggression effects adolescent adjustment. Specifically, this study explored the role of adolescents’ emotional insecurity and adrenocortical reactivity in the relationship between these variables. Overall, results indicated that adolescents’ emotional insecurity mediates the relationship between marital aggression and adolescents’ depression and anxiety, and adrenocortical reactivity moderates this effect.

The first hypothesis predicted that the impact of marital aggression on adolescents’ adjustment would be mediated by their emotional insecurity. Analyses revealed that emotional insecurity significantly mediated the relationship between interparental aggression and adolescents’ self-reports of depression and anxiety. Results support the assertion presented by Davies, Winter and Cicchetti (2006) that emotional security is an important intervening construct in instances of extreme adversity in the family context, such as interparental aggression. In addition, these results contribute to the literature by examining these pathways in adolescents, an understudied group in this context with a known vulnerability to the effects of emotional insecurity (Cummings & Davies, 2010).

The second hypothesis required a test of moderated mediation to determine the effect of adolescents’ adrenocortical reactivity on the mediating role of emotional insecurity in the relationship between exposure to interparental aggression and adolescent adjustment. Consistent with other evidence in the literature, differences in patterns of physiological reactivity to exposure to family conflict related to vulnerability to the effect of emotional insecurity on adjustment outcomes (Davies, et al., 2008). These results furthermore lend support to the notion that there may be an important association between adrenocortical reactivity and regulatory responses associated with emotional security, suggesting that the presence of both atypical patterns of adrenocortical activity in the context of family conflict may signal increased vulnerability to the negative ramifications of emotional insecurity on adolescents. This conclusion also supports the contention that adolescence is a time of particular vulnerability to the negative consequences of exposure to interparental aggression and violence (Cummings & Davies, 1994).

Results from this study cannot generalize to clinical populations, but there are implications for members of the community who fall both above and below clinical cut-off points but still expose their children to problematic behaviors. However, given evidence for the high likelihood that adolescents will become involved in interparental conflicts that involve physical aggression, it is possible that the patterns of maladjustment indicated in this study may be the result of adolescents’ participation in physically aggressive conflicts rather than simply witnessing physical aggression between their parents, that is, witnessing and participating may both be factors in adjustment outcomes. This could not be controlled for in the current study; however, in studies that do control for child abuse, exposure to interparental violence has been associated with internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (Holt, Buckley, & Whelan, 2008).

Despite its limitations, the present study makes several important contributions. The current study extends research on the role of emotional insecurity in the literature on marital conflict more generally to examine its meditational capacity in extreme cases of marital conflict, that is, interparental aggression and violence. In spite of the inability to make causal inferences based on these cross-sectional data, results of the present study contribute to a limited body of literature on the relationship between interparental aggression and adolescent adjustment in particular, and can inform theory moving forward. The present study also highlights the potential for adolescents’ adrenocortical reactivity in this context to signal a vulnerability to the negative consequences of emotional insecurity. Furthermore, the current study extends this to clarify the impact of exposure to violence that is perpetrated by mothers as well as fathers. There are also implications for identifying and intervening in individuals at risk for maladjustment because of these specific kinds of deficits in their family environments.

Finally, the present study lends itself well to interesting extensions in future research with regard to adolescents’ development. First, the focus of the current study is on maladaptive developmental patterns in adolescence. Future research should explore emotional security and adrenocortical reactivity as an explanatory mechanism for the cases in which adolescents develop adaptively despite adverse family environments; in the same way that emotional insecurity acts as a mechanism through which exposure to interparental aggression impacts maladaptation, emotional security may serve as a protective mechanism that fosters adaptive functioning in the face of exposure to threatening aspects of the family environment. This work could also be extended to explore the impact of exposure to interparental aggression on adolescents’ own relationships as early adolescents are beginning to wrestle with the stage-salient task of establishing romantic relationships for the first time. Another interesting extension of this work for future research would be to track the role of emotional insecurity in the intergenerational transmission of aggressive and violent behaviors.

The current study addresses a societal issue of grave concern: intimate partner violence, and the environment of threat that those maladaptive patterns of behavior create for a developing adolescent. Results of this study support the notion that exposure to this kind of family adversity has deleterious effects for adolescents’ development, and also that emotional insecurity plays an important role in this relationship, the magnitude of which is impacted by physiological reactivity. The current study highlights several critical processes that are involved in instances of extreme family adversity and also lays the ground work for several directions of future research related to these exceedingly consequential issues.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01 MH57318 from the National Institute of Mental Health awarded to Patrick T. Davies and E. Mark Cummings.

References

- Achenbach TM, Howell CT, Quay HC, Connors CK. National survey of problems and competencies among four to sixteen-year-olds. Monographs for the Society for Research in Child Development. 1991;56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Personality, adrenal steroid hormones, and resilience in maltreated children: A multilevel perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:787–809. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. New York and London: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research and clinical implications. NY: Guilford Publications, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, El-Sheikh M, Kouros CD, Keller PS. Children’s skin conductance reactivity as a mechanism of risk in the context of parental depressive symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(5):436–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E, Schermerhorn A, Davies P, Goeke-Morey M, Cummings J. Interparental discord and child adjustment: Prospective investigations of emotional security as an explanatory mechanism. Child Development. 2006;77(1):132–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital Conflict and Child Adjustment: An Emotional Security Hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116(3):387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Exploring children’s emotional security as a mediator of the link between marital relations and child adjustment. Child Development. 1998;69(1):124–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Forman EM, Rasi JA, Stevens KI. Assessing children’s emotional security in the interparental relationship: The security in the interparental subsystem scales. Child Development. 2002;73:544–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM. Adrenocorticol underpinnings of children’s psychological reactivity to interparental conflict. Child Development. 2008;79(6):1693–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P, Winter M, Cicchetti D. The implications of emotional security theory for understanding and treating childhood psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18(3):707–735. doi: 10.1017/s0954579406060354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Cummings EM, Kouros CD, Elmore-Staton L, Buckhalt J. Marital psychological and physical aggression and children’s mental and physical health: Direct, mediated, and moderated effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:138–148. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Flanagan E. Parental problem drinking and children's adjustment: Family conflict and parental depression as mediators and moderators of risk. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29(5):417–432. doi: 10.1023/a:1010447503252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SE, Davies C, DiLillo D. Exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent outcomes. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to interparental violence in childhood and psychosocial adjustment in young adulthood. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22(5):339–357. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeke-Morey M, Cummings E, Harold G, Shelton K. Categories and continua of destructive and constructive marital conflict tactics from the perspective of U.S. Welsh children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(3):327–338. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger D, Kivlighan K, Fortunato C, Harmon A, Hibel L, et al. Integration of salivary biomarkers into developmental and behaviorally-oriented research: Problems and solutions for collecting specimens. Physiology & Behavior. 2007;92(4):583–590. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2008;32(8):797. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell K. Resilience and psychopathology in children exposed to family violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2011;16(6):562–569. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes H, Graham-Bermann S. Children of battered women: Impact of emotional abuse on adjustment and development. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 1999;1(2):23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK. Moderators and mediators of the effects of interparental conflict on children’s adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26(3):199–212. doi: 10.1023/a:1022672201957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK. Assessing the links between interparental conflicts and child adjustment: The Conflicts and Problem-solving Scales. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10(4):454–473. [Google Scholar]

- Klostermann KC, Fals-Stewart W. Intimate partner violence and alcohol use: Exploring the role of drinking in partner violence and its implications for intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:587–597. [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Graham-Bermann S. Parenting in battered women: The effects of domestic violence on women and their children. Journal of Family Violence. 2001;16(2):171–192. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Torteya C, Bogat GA, von Eye A, Levendosky AA. Resilience among children exposed to domestic violence: The role of risk and protective factors. Child Development. 2009;80(2):562–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Jouriles EN. Marital aggression and child behavior problems: Research findings, mechanisms, and intervention strategies. The Behavior Therapist. 1991;14:189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt T, Caspi A. Annotation: Implications of violence between intimate partners for child psychologists and psychiatrists. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1998;39(2):137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89(6):852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradovic J, Bush N, Stamperdahl J, Adler N, Boyce W. Biological sensitivity to context: The interactive effects of stress reactivity and family adversity on socioemotional behavior and school readiness. Child Development. 2010;81(1):270–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins S, Graham-Bermann S. Violence exposure and the development of school-related functioning: Mental health, neurocognition, and learning. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2012;17(1):89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter B, O'Leary KD. Marital discord and childhood behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1980;8(3):287–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00916376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scales in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20(2):149–165. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. What I think and feel: A revised measure of children's manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6(2):271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Sroufe LA. Developmental psychopathology: Concepts and challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:265–296. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Slep A, O'Leary S. Parent and partner violence in families with young children: Rates, patterns, and connections. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(3):435–444. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansbury K, Gunnar MR. Adrenocortical activity and emotion regulation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:108–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]