Abstract

Peptic ulcer disease continues to be issue especially due to its high prevalence in the developing world. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection associated duodenal ulcers should undergo eradication therapy. There are many regimens offered for H. pylori eradication which include triple, quadruple, or sequential therapy regimens. The central aim of this systematic review is to evaluate the evidence for H. pylori therapy from a meta-analytical outlook. The consequence of the dose, type of proton-pump inhibitor, and the length of the treatment will be debated. The most important risk factor for eradication failure is resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazole.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Peptic ulcer disease, Systematic review, Proton-pump inhibitors

Core tip: This review will discuss the different traits of treatment regimens for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)and will also give an insight about some unconventional and novel treatment strategies from a meta-analytic viewpoint. This review summarizes the recommendations and level of evidence regarding the role of the dose, type of proton-pump inhibitor, and the length of the treatment. The review also discusses the various regimes for second line therapy, sequential therapy and new alternate/adjuvant therapies for H. pylori therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Marshall and Warren[1] identified and subsequently cultured the Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in 1982. This organism is associated with chronic gastritis[2], most peptic ulcers[3], and gastric adenocarcinoma[4] and lymphoma[5]. A meta-analysis that included seven controlled trials (all in areas with a high incidence of gastric cancer) found significantly lower rates of gastric cancer (1.1% vs 1.7%) in patients randomized to eradication (OR = 0.65, 95%CI: 0.43-0.98)[6].

There are numerous regimens recommended for H. pylori eradication which include triple, quadruple, or sequential therapy regimens. Currently regimens that use proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) in combination with several antibiotics such as clarithromycin, amoxycillin and metronidazole have been highly successful for H. pylori eradication[7,8]. Numerous treatments have been evaluated for H. pylori therapy in randomized controlled trials[9-11]. In spite of the numerous studies, the ideal schedule is still controversial. This review will discuss the different traits of treatment regimens for H. pylori and will also give an insight about some unconventional and novel treatment strategies from a meta-analytic viewpoint.

LITERATURE SEARCH

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses PRISMA guidelines where possible in performing our systematic review[12]. We performed a systematic search through MEDLINE (from 1950), PubMed (from 1946), EMBASE (from 1949), Current Contents Connect (from 1998), Cochrane library, Google scholar, Science Direct, and Web of Science to July 2013. The search terms included “Helicobacter pylori, gastric cancer, intestinal metaplasia, gastric atrophy, dysplasia, prevention, treatment, and eradication”. In addition, we identified relevant trials from the reference list of each selected article. Selection criteria were established. To be eligible, the studies have to be systematic reviews or meta-analyses about various eradication regimes and alternate remedies. No language restrictions were used in either the search or study selection. The reference lists of relevant articles were also searched for appropriate studies. A search for unpublished literature was not performed.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF THE DIFFERENT PPI DOSES IN H. PYLORI ERADICATION THERAPY?

A combination of a double dose of proton pump inhibitor plus two antibiotics is the standard regimen for H. pylori infection. A report also suggests that the use of single dose of proton pump inhibitor is similarly efficacious[13]. Unitat de Malalties Digestives[13] conducted a MEDLINE search for their meta-analysis comparing single and double dose of a proton pump inhibitor head to head in triple therapy for H. pylori eradication. As a result thirteen studies were included (double dose of proton pump inhibitor: 1211 patients, single dose of proton pump inhibitor: 1180 patients). Eradication rates with double doses of proton pump inhibitor (80 mg of pantaprazole, 60 mg of lansoprazloe, 40 mg of omeprazole) were greater in both the intention-to-treat analysis and per protocol analysis. To summarize, the use of high-dose (twice a day) PPI increases the effectiveness of triple therapy compared to a single dose PPI (level of evidence 1b, grade of recommendation A)[14].

DIFFERENT PPIS IN H. PYLORI ERADICATION THERAPY

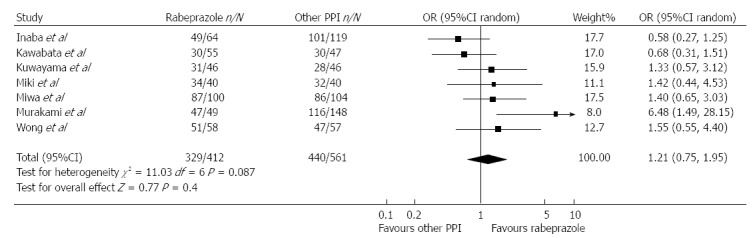

In a systematic review published by Gisbert et al[15] low doses of rabeprazole (10 mg bid), reached similar H. pylori eradication rates to omeprazole and lansoprazole (Figure 1). A systematic review regarding lansoprazole demonstrates a greater efficacy in eradicating H. pylori. 1076 patients were prescribed rabeprazole and 1150 with other PPIs. This efficacy is comparable to that of other PPIs[16]. Twelve studies equating pantoprazole and other PPIs were included in a meta-analysis by Gisbert et al[17] The average H. pylori eradication rate for using pantoprazole plus antibiotics was similar in the two cohorts. A sub-analysis was no different statistically which included only studies comparing pantoprazole with omeprazole, or pantoprazole with lansoprazole. The subgroup analysis of six studies administering equivalent doses of all PPIs established statistically homogeneous results with pantoprazole.

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of studies comparing Helicobacter pylori eradication with rabeprazole 10 mg bid vs omeprazole 20 mg bid or lansoprazole 30 mg bid in triple therapies[15]. PPI: Proton pump inhibitor.

Shanghai Institute of Digestive Disease[18] screened 75 articles and included 11 RCTs (2159 subjects) in their meta-analysis of esomeprazole-based triple therapy. The mean H. pylori eradication rates (intention-to-treat, ITT) with esomeprazole + antibiotics were 6% higher than other PPI therapies with a statistically significant odd ratio of 1.38. A subgroup analysis of six selected high-quality studies produced statistically homogeneous results. In 2004, Gisbert et al[19] performed a similar meta-analysis and published analogous results. Vergara et al[20] performed a MEDLINE search for their meta-analysis of fourteen studies that compared the efficacy of different proton-pump inhibitors in triple therapy showed similar results. The effectiveness of different proton-pump inhibitors is comparable in standard triple therapy.

DURATION OF PPI-BASED TRIPLE THERAPIES

An extended period of therapy (2 wk against 1 wk) could be more efficacious in eradicating infection but this is contentious[21,22]. Fuccio et al[21] performed a meta-analysis with 21 studies. Diarrhea and dysgeusia were the most commonly described side effects (5%). They concluded that prolonging the period of PPI-clarithromycin-containing triple treatment from 7 to 10-14 d increases the eradication rate by about 5%. This is currently equates to level of evidence 1b and grade of recommendation A[14].

PPI-BASED TRIPLE REGIMENS AS OPPOSED TO QUADRUPLE THERAPY

The University of North Texas Health Science Center performed a meta-analysis with 93 studies (10178 participants)[23]. For triple therapies, clarithromycin resistance had a larger effect on treatment effectiveness than nitroimidazole resistance. Metronidazole resistance reduced effectiveness by a quarter in triple therapies containing a nitroimidazole, tetracycline and bismuth, while effectiveness was reduced by only 14% when a proton pump inhibitor was added to the regimen. The occurrence of nitroimidazole and clarithromycin resistance has increased considerably; standard triple therapies are inadequate to eradicate H. pylori. Quadruple regimens are usually used as second line; they should be considered as first-line, essentially in areas of high drug resistance however, it may not be effective in context of concomitant clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance. In regions of low clarithromycin resistance, clarithromycin- containing treatments are recommended for first-line empirical treatment. However, Bismuth-containing quadruple treatment is also an alternative. (level of evidence 1a, grade of recommendation A)[14]. In areas of high clarithromycin resistance, bismuth-containing quadruple treatments are recommended for first-line empirical treatment. If this regimen is not available a non-bismuth quadruple treatment is recommended (level of evidence 1a, grade of recommendation A)[14].

SEQUENTIAL THERAPY FOR HELICOBACTER PYLORI INFECTION

Multiple randomized trials have demonstrated that sequential therapy and concomitant quadruple therapy are equally effective for eradication of H. pylori in treatment-naïve patients. Sequential therapy for 14 d may be more effective in eradicating H. pylori as compared with triple therapy in regions where clarithromycin resistance is high and metronidazole resistance is low[24-27]. This difference in antimicrobial resistance patterns may explain the seemingly contradictory results in two randomized controlled trials conducted in Taiwan and Latin America[28,29]. In a randomized controlled trial in Taiwan, 900 adults with H. pylori were assigned to 14-d triple therapy (lansoprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin) or 14-d sequential therapy (lansoprazole and amoxicillin for seven days followed by lansoprazole, clarithromycin, and metronidazole for seven days) or 10-d sequential therapy (lansoprazole and amoxicillin for five days followed by lansoprazole, clarithromycin, and metronidazole for five days)[29]. In this study, 14-d sequential therapy was significantly more likely to eradicate H. pylori as compared with the 14-d triple therapy. In contrast, in a randomized trial of 1463 H. pylori infected patients in Latin America, 14-d triple therapy (lansoprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin) had higher eradication rates than five-day concomitant quadruple therapy (lansoprazole, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole) and 10-d clarithromycin containing sequential therapy (82%, 74% and 77%, respectively)[28]. However, among 1091 patients in whom H. pylori had been successfully eradicated, one-year recurrence rates were not significantly different based on the antibiotic regimen[30].

Horvath et al[31] ten RCTs involving a total of 857 children. This resulted in a statistically significant relative risk of 1.14 and with a number needed to treat of 15 for the eradication rate for sequential therapy. Sequential therapy had greater efficacy to 7-d standard triple therapy, however failed to statistical significant better results than 10-d or 14-d triple therapy. The risks of adverse effects were similar in the different groups.

In 2008 University of Louisville[32] concluded that sequential therapy is better than standard triple therapy for eradication of H. pylori infection. However, there was clear evidence of publication bias.

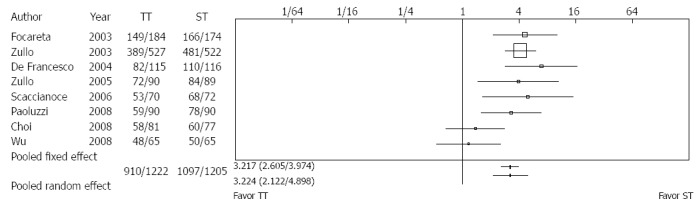

Gatta et al[33] included ten RCTs with 3006 adults. The eradication rate for H. pylori with sequential therapy (ST) compared with triple therapy (TT) produced a number needed to treat of 6. In patients with clarithromycin resistance, eradication with ST was clearly 10 times more superior to TT. However, the number of studies was small (Figure 2). In regions of high clarithromycin resistance, bismuth-containing quadruple treatments are suggested for first-line empirical treatment if this is unavailable, sequential treatment is the level of evidence 1a and with a grade A recommendation[14].

Figure 2.

Sequential vs triple therapy lasting 7 d[33]. ST: Sequential therapy; TT: Triple therapy.

PPIS AS OPPOSED TO RANITIDINE BISMUTH CITRATE-BASED REGIMENS

Gisbert et al[9] performed a meta-analysis using randomized controlled trials that compared PPI vs ranitidine bismuth citrate (RBC) plus two antibiotics for 1 wk. The mean H. pylori eradication with 7-d RBC-clarithromycin-amoxicillin, RBC-clarithromycin-nitroimidazole, and RBC-amoxicillin-nitroimidazole were 83%, 86%, and 71%, respectively. They concluded the effectiveness of ranitidine bismuth citrate and PPI-based triple regimens were similar. Nonetheless, equating PPI vs RBC plus clarithromycin and a nitroimidazole demonstrated superior cure rates with RBC than with PPI.

Two other meta-analyses published in Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics by the University Medical Centre St[34] and University Hospital of ‘La Princesa’[35] proposed similar conclusions. The effectiveness of RBC and PPI-based triple regimens are similar to the clarithromycin-amoxicillin or the amoxicillin-metronidazole combination. Nevertheless, RBC seems to have a greater effectiveness than PPI when clarithromycin and a nitroimidazole are the antibiotics administered.

H. PYLORI ERADICATION WHEN FIRST-LINE THERAPY FAILS: QUINOLONE-BASED RESCUE REGIMENS

Fluoroquinolones are inhibitors of bacterial DNA synthesis by inhibiting DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV[36]. The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University[37] in 2010 conducted a meta-analysis compare the efficacy and safety of clarithromycin and second-generation fluoroquinolone-based triple therapy vs bismuth-based quadruple therapy for the treatment of persistent H. pylori infection. Thirteen RCTs equated levofloxacin-based triple therapy to bismuth-based quadruple therapy; the eradication rates of the two regimens were similar. However, the eradication rates established greater efficacy for the 10-d levofloxacin-based triple therapy over 7-d bismuth-based quadruple therapy and was better accepted than bismuth-based quadruple therapy with lower incidence of adverse events and lower rates of cessation of therapy due to side effects.

Similar meta-analyses performed by University of Michigan Medical Center[38] and University Hospital of “La Princesa”[39] concluded that 10-d course Quinolone triple therapy has superior efficacy than 7-d bismuth-based quadruple therapy in the treatment of stubborn H. pylori infection. Evidence-Based Medicine Center of Lanzhou University[40] proved that moxifloxacin-based triple therapy is superior and does not rise the frequency of adverse events equated to clarithromycin-based triple therapy. Fluoroquinolone-based triple therapy is more active and does not increase the incidence of overall side effects compared to clarithromycin-based triple therapy in the treatment of H. pylori infection. H. pylori resistant to a PPI-clarithromycin containing therapy, either a bismuth containing quadruple therapy or levofloxacin containing triple therapy is suggested (level of evidence 1b, grade of recommendation A)[14]. The first-line regimens for H. pylori eradication have been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

First-line regimens for Helicobacter pylori eradication[88]

| Regimen | Standard dose PPI bid (esomeprazole is qid), clarithromycin 500 mg bid, amoxicillin 1000 mg bid for 10–14 d | Standard dose PPI bid, clarithromycin 500 mg bid metronidazole 500 mg bid for 10–14 d | Bismuth subsalicylate 525 mg po qid metronidazole 250 mg po qid, tetracycline 500 mg po qid, ranitidine 150 mg po bid or standard dose PPI qid to bid for 10–14 d | PPI + amoxicillin 1 g bid 5 d followed by PPI, clarithromycin 500 mg, tinidazole 500 mg bid for 5 d |

| Note | Consider in nonpenicillin allergic patients who have not previously received a macrolide | Consider in penicillin allergic patients who have not previously received a macrolide or are unable to tolerate bismuth quadruple therapy | Consider in penicillin allergic patients | Requires validation in North America |

PPI: Proton-pump inhibitors.

ADVERSE EFFECTS

The incidence of side effects is up to half of the individuals taking one of the triple therapies[41,42]. These are typically minor; fewer than 10 percent of individuals halt treatment due to side effects[42].

The most common adverse effect reported due to metronidazole or clarithromycin is a metallic taste[43]. Metronidazole can lead to a disulfiram-like reaction, peripheral neuropathy, and seizures[43]. Clarithromycin can cause taste alteration, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and rarely QT prolongation[43]. Doxycycline and tetracycline can lead to a photosensitivity reaction and it is contraindicated in pregnant women and young children. Amoxicillin can cause diarrhea or skin rash[43].

Levofloxacin has been linked with anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort[43]. In institutional settings with outbreaks of the epidemic fluoroquinolone-resistant strain of Clostridium difficile (C. difficile), use of fluoroquinolones has been a risk factor for development of C. difficile-associated diarrhea[44]. Central nervous system toxicities of levofloxacin including mild headache and dizziness have predominated, followed by insomnia and alterations in mood. Other adverse effects comprise of rashes and other allergic reactions, tendinitis and tendon rupture, QT prolongation, hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, and hematologic toxicity[43].

Common side effects of Bismuth subcitrate are blackening of faeces, darkening of teeth and tongue. The infrequent adverse effects are nausea, vomiting, dizziness, headache and diarrhea[43].

The primary concern with bismuth compounds is bismuth intoxication; this was a problem primarily when bismuth subgallate was used for prolonged periods at high doses. Bismuth absorption varies with the specific form of bismuth; absorption is much greater with colloidal bismuth subcitrate than with bismuth subsalicylate[45]. Concurrent administration of H2 receptor antagonists increases bismuth absorption from CBS, but not from bismuth subsalicylate[46]. Nevertheless, significant clinical toxicity has not been reported in clinical trials with colloidal bismuth subcitrate or bismuth subsalicylate[47,48]. Bismuth should be avoided or serum bismuth concentrations monitored in patients with renal failure[49].

The subsalicylate moiety in bismuth subsalicylate is converted to salicylic acid and absorbed; however, salicylate in the absence of the acetyl group does not inhibit platelet function or appear to share the same high risk of aspirin for gastrointestinal bleeding[50,51]. However, the salicylate from bismuth subsalicylate will contribute to serum salicylate levels and cause salicylate toxicity, and combination with other salicylate products should therefore be avoided.

Proton pump inhibitors are usually well accepted. Common side effects include headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, constipation and flatulence. Uncommon adverse effects are rash, itch, dizziness, fatigue, drowsiness, insomnia and dry mouth[43]. There have been some concerns regarding long term use of proton pump inhibitors.

Recently, a meta-analysis of 42 observational studies that included 313000 patients found that PPI use was linked with an increased risk of both incident and recurrent C. difficile infection (OR = 1.7, 95%CI: 1.5-2.9 and 2.5, 95%CI: 1.2-5.4, respectively)[52]. A meta-analysis of 31 studies found that patients taking PPIs or H2 receptor antagonists were at increased risk for pneumonia, with an odds ratio of 1.27 (95%CI: 1.11-1.46) with PPIs and 1.22 (95%CI: 1.09-1.36) with H2 receptor antagonists[53]. Hypomagnesemia due to reduced intestinal absorption has been described[54]. Yu et al[55] included 11 studies to evaluate the relationship between proton pump inhibitor or H2 receptor antagonist use and fractures (1084560 patients with 62210 PPI users, 71339 patients with hip fractures, 161179 patients with any-site fractures, and 5728 patients with spine fractures). The risk of hip fracture was increased among PPI users compared with nonusers (RR = 1.30, 95%CI: 1.19-1.43). There was also an increased risk of spine fracture (RR = 1.56, 95%CI: 1.31-1.85) and any-site fracture (RR = 1.16, 95%CI: 1.02-1.32)[55].

ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Probiotics

The intestinal tract is host to a vast ecology of microbes, which are necessary for health, but also have the potential to contribute to the development of diseases by a variety of mechanisms. Perturbations in intestinal epithelial barrier function or innate immune bacterial killing, for example, can lead to an inflammatory response caused by increased uptake of bacterial and food antigens that stimulate the mucosal immune system[56,57]. The maximum understanding has been in the inflammatory bowel diseases, ulcerative colitis[58], Crohn’s disease[59], and pouchitis[60-62], although clinical trials are emerging in several other conditions.

Wang et al[63] proposed that regular consumption of yogurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus or Bifidobacterium lactis successfully curbed H. pylori infection in human beings. The Medical University of Warsaw[64] identified five RCTs that compared with placebo or no intervention, Saccharomyces boulardii given along with triple therapy. When S. boulardii was given along with triple therapy a significant increase in eradication rates was observed and lowered the rate of side effects principally of diarrhea.

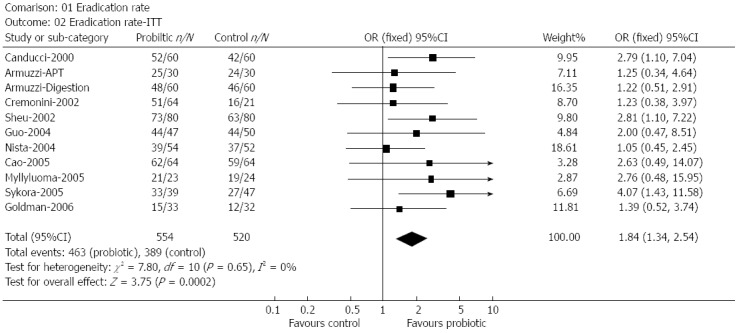

The Shanghai Institute of Digestive Disease[65] performed a meta-analysis using 14 randomized trials with 1671 subjects. The pooled H. pylori eradication rates improved significantly with an odds ratio of 1.84 the incidence of total side effects was reduced by almost 14% and reduced diarrhea significantly (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The effect of probiotics supplementation vs without probiotics on eradication rates by intention-to-treat analysis[65]. n: Number of successful eradication; N: Number of participants; ITT: Intention-to-treat.

Zou et al[66] identified nine randomized trials (n = 1343) in their meta-analysis that investigated the role of lactoferrin. The pooled H. pylori eradication rates improved significantly with an odds ratio of 2.26 and the rate of total side-effects reduced by half, particularly nausea.

Probiotics have reduced the incidence of total side effect H. pylori therapy-related side effects and could be an efficacious strategy in amplifying eradication rates of anti-H. pylori therapy and might be useful for patients with eradication failure. (level of evidence 5, grade of recommendation D)[14].

Chinese herbal therapy

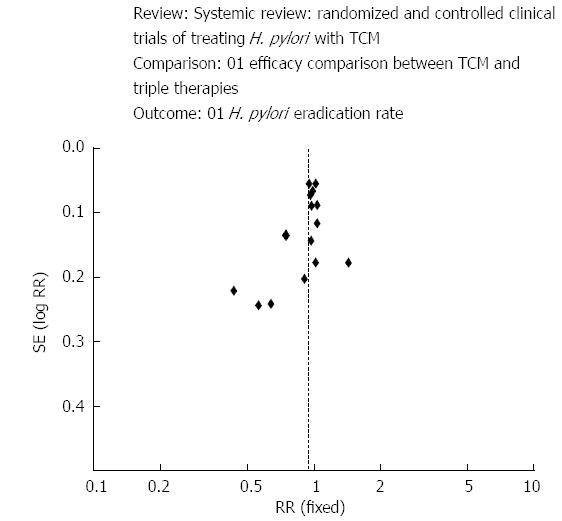

Herbs have been used conventionally for the management of a extensive variety of ailments, including gastrointestinal ailments[67]. Department of Gastroenterology at Shuguang Hospital[68] assessed the efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine by performing a systematic review with the help of sixteen trials. Large statistical heterogeneity was observed among the trials. The mean eradication rates subsequent traditional Chinese medicine and triple therapy were similar and the incidence of side effects was 15 times lower with Chinese medicine (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Clinical trials treating Helicobacter pylori with traditional Chinese medicine[68]. H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; TCM: Traditional Chinese medicine.

Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine[69] reported that oral administration with HZJW and ranitidine in rodent experimental models considerably reduced the ulcerative lesion index in a dose-dependent way.

Liu et al[70] investigated the bactericidal effects of Jinghua Weikang Capsule and its individual herb Chenopodium ambrosioides L. against antibiotic-resistant H. pylori. In vitro they are considered to be active against antibiotic-resistant H. pylori.

Many Brazilian medicinal plants like Davilla elliptica and Davilla nitida[71], Alchornea glandulosa[72], Mouririelliptica[73], Calophyllum brasiliense Camb[74-76], Hancornia speciosa[77], Strychnos species[78] and many more have been evaluated for their anti-H. pylori effect in vitro.

Honey

Honey is frequently utilized by numerous individuals with the trust due to its antimicrobial properties, cost effectiveness and accessibility. It is utilized as a wound antiseptic and cough syrup. University of Buea[79] assessed the antimicrobial potential of honeys (Manuka™, Capillano®, Eco- and Mountain) at diverse concentrations against of H. pylori, no statistically significant difference was eminent among the honeys at diverse concentrations. The antimicrobial properties of these honeys at diverse concentrations were highly analogous to clarithromycin. A prospective randomized trial would help in deciding its efficacy.

Green tea

Tea extracts for instance catechins deter the growth of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Staphylococcus epidermidis, Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae) O1, V. cholerae non-O1, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio mimicus, Campylobacter jejuni and Plesiomonas shigelloides in vitro[80] and have antimicrobial activity against meticillin-resistant S. aureus in vitro[81].

University of Massachusetts Medical School[82] assessed the antimicrobial activity of green tea against Helicobacter felis and H. pylori in vitro and assessed the consequence of green tea on the pathogenesis of Helicobacter-induced gastritis in an animal experimental model. This resulted in significant inhibition of Helicobacter and averts gastric mucosal inflammation if consumed before being infected with Helicobacter.

Similarly an Italian study[83] proposed that in H. pylori-infected mice, Ethanol-free red wine and green tea mixture considerably reduced gastritis, restricted the localization of bacteria and VacA to the gastric mucosa. Another study from Japan[84] concluded that H. pylori was significantly decreased by Green tea catechins-sucralfate in Mongolian gerbils.

Recently, Yonsei University[85] performed a meta-analysis regarding green tea consumption and stomach cancer risk. A total of 18 studies were incorporated in the publication which demonstrated a statistically significant of 14% reduction in the risk of stomach cancer with high green tea consumption. Some studies have suggested that Green tea has antimicrobial activity[86,87], which can extend to H. pylori. Natural remedies could be used in the future for inhibition and management of Helicobacter-induced gastritis in Homo sapiens however, further studies are required in this field.

CONCLUSION

The advancement of H. pylori treatment over the years has been admirable. Bismuth-containing quadruple regimens for 7-14 d are alternative first-line treatment option. Sequential therapy for 10 d has revealed potential. Bismuth quadruple therapy is the most commonly used rescue regimen in patients with persistent H. pylori. The first-line regimens for H. pylori eradication are listed in Table 1. Current facts propose that a PPI, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin for 10 d is superior to bismuth quadruple therapy for persistent H. pylori infection[88]. The current literature suggests that probiotics[64] and Chinese herbal therapy[68] might be beneficial in eradicating H. pylori. Further research in the area of alternative medicine might help us achieve higher rates of eradication and reduce side effects.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Alsolaiman MM, Figura N, Sugimoto M, Vyas D S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–1181. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciociola AA, McSorley DJ, Turner K, Sykes D, Palmer JB. Helicobacter pylori infection rates in duodenal ulcer patients in the United States may be lower than previously estimated. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1834–1840. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eslick GD, Lim LL, Byles JE, Xia HH, Talley NJ. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2373–2379. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zucca E, Bertoni F, Roggero E, Bosshard G, Cazzaniga G, Pedrinis E, Biondi A, Cavalli F. Molecular analysis of the progression from Helicobacter pylori-associated chronic gastritis to mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue lymphoma of the stomach. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:804–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803193381205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Laterza L, Cennamo V, Ceroni L, Grilli D, Bazzoli F. Meta-analysis: can Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment reduce the risk for gastric cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:121–128. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-2-200907210-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gisbert JP, González L, Calvet X, García N, López T, Roqué M, Gabriel R, Pajares JM. Proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin and either amoxycillin or nitroimidazole: a meta-analysis of eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1319–1328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laine L, Fennerty MB, Osato M, Sugg J, Suchower L, Probst P, Levine JG. Esomeprazole-based Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy and the effect of antibiotic resistance: results of three US multicenter, double-blind trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3393–3398. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gisbert JP, Gonzalez L, Calvet X. Systematic review and meta-analysis: proton pump inhibitor vs. ranitidine bismuth citrate plus two antibiotics in Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2005;10:157–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2005.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qasim A, Sebastian S, Thornton O, Dobson M, McLoughlin R, Buckley M, O’Connor H, O’Morain C. Rifabutin- and furazolidone-based Helicobacter pylori eradication therapies after failure of standard first- and second-line eradication attempts in dyspepsia patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:91–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatta L, Zullo A, Perna F, Ricci C, De Francesco V, Tampieri A, Bernabucci V, Cavina M, Hassan C, Ierardi E, et al. A 10-day levofloxacin-based triple therapy in patients who have failed two eradication courses. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:45–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vallve M, Vergara M, Gisbert JP, Calvet X. Single vs. double dose of a proton pump inhibitor in triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1149–1156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gisbert JP, Khorrami S, Calvet X, Pajares JM. Systematic review: Rabeprazole-based therapies in Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:751–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bazzoli F, Pozzato P, Zagari M, Fossi S, Ricciardiello L, Nicolini G, Berretti D, De Luca L. Efficacy of lansoprazole in eradicating Helicobacter pylori: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 1998;3:195–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1998.08029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gisbert JP, Khorrami S, Calvet X, Pajares JM. Pantoprazole based therapies in Helicobacter pylori eradication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:89–99. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200401000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Fang JY, Lu R, Sun DF. A meta-analysis: comparison of esomeprazole and other proton pump inhibitors in eradicating Helicobacter pylori. Digestion. 2006;73:178–186. doi: 10.1159/000094526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gisbert JP, Pajares JM. Esomeprazole-based therapy in Helicobacter pylori eradication: a meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vergara M, Vallve M, Gisbert JP, Calvet X. Meta-analysis: comparative efficacy of different proton-pump inhibitors in triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:647–654. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuccio L, Minardi ME, Zagari RM, Grilli D, Magrini N, Bazzoli F. Meta-analysis: duration of first-line proton-pump inhibitor based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:553–562. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vakil N, Connor J. Helicobacter pylori eradication: equivalence trials and the optimal duration of therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1702–1703. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischbach L, Evans EL. Meta-analysis: the effect of antibiotic resistance status on the efficacy of triple and quadruple first-line therapies for Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:343–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moayyedi P, Malfertheiner P. Editorial: Sequential therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a new guiding light or a false dawn? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3081–3083. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zullo A, De Francesco V, Hassan C, Morini S, Vaira D. The sequential therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a pooled-data analysis. Gut. 2007;56:1353–1357. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.125658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaira D, Zullo A, Vakil N, Gatta L, Ricci C, Perna F, Hassan C, Bernabucci V, Tampieri A, Morini S. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:556–563. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim YS, Kim SJ, Yoon JH, Suk KT, Kim JB, Kim DJ, Kim DY, Min HJ, Park SH, Shin WG, et al. Randomised clinical trial: the efficacy of a 10-day sequential therapy vs. a 14-day standard proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori in Korea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1098–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenberg ER, Anderson GL, Morgan DR, Torres J, Chey WD, Bravo LE, Dominguez RL, Ferreccio C, Herrero R, Lazcano-Ponce EC, et al. 14-day triple, 5-day concomitant, and 10-day sequential therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection in seven Latin American sites: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378:507–514. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liou JM, Chen CC, Chen MJ, Chen CC, Chang CY, Fang YJ, Lee JY, Hsu SJ, Luo JC, Chang WH, et al. Sequential versus triple therapy for the first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori: a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:205–213. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgan DR, Torres J, Sexton R, Herrero R, Salazar-Martínez E, Greenberg ER, Bravo LE, Dominguez RL, Ferreccio C, Lazcano-Ponce EC, et al. Risk of recurrent Helicobacter pylori infection 1 year after initial eradication therapy in 7 Latin American communities. JAMA. 2013;309:578–586. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horvath A, Dziechciarz P, Szajewska H. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:534–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923–931. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-12-200806170-00226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Vaira D. Sequential therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults and children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3069–379; quiz 1080. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janssen MJ, Van Oijen AH, Verbeek AL, Jansen JB, De Boer WA. A systematic comparison of triple therapies for treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection with proton pump inhibitor/ ranitidine bismuth citrate plus clarithromycin and either amoxicillin or a nitroimidazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:613–624. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gisbert JP, González L, Calvet X, Roqué M, Gabriel R, Pajares JM. Helicobacter pylori eradication: proton pump inhibitor vs. ranitidine bismuth citrate plus two antibiotics for 1 week-a meta-analysis of efficacy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1141–1150. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377–392. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.377-392.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Huang X, Yao L, Shi R, Zhang G. Advantages of Moxifloxacin and Levofloxacin-based triple therapy for second-line treatments of persistent Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta analysis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2010;122:413–422. doi: 10.1007/s00508-010-1404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saad RJ, Schoenfeld P, Kim HM, Chey WD. Levofloxacin-based triple therapy versus bismuth-based quadruple therapy for persistent Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:488–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gisbert JP, Morena F. Systematic review and meta-analysis: levofloxacin-based rescue regimens after Helicobacter pylori treatment failure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wenzhen Y, Kehu Y, Bin M, Yumin L, Quanlin G, Donghai W, Lijuan Y. Moxifloxacin-based triple therapy versus clarithromycin-based triple therapy for first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Intern Med. 2009;48:2069–2076. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischbach LA, van Zanten S, Dickason J. Meta-analysis: the efficacy, adverse events, and adherence related to first-line anti-Helicobacter pylori quadruple therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1071–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Boer WA, Tytgat GN. The best therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: should efficacy or side-effect profile determine our choice? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:401–407. doi: 10.3109/00365529509093298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Australian Medicines Handbook 2014 (online) Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd, 2014. Available from: http://www.amh.net.au.

- 44.McCusker ME, Harris AD, Perencevich E, Roghmann MC. Fluoroquinolone use and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:730–733. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.020385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nwokolo CU, Gavey CJ, Smith JT, Pounder RE. The absorption of bismuth from oral doses of tripotassium dicitrato bismuthate. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1989;3:29–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1989.tb00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nwokolo CU, Prewett EJ, Sawyerr AM, Hudson M, Pounder RE. The effect of histamine H2-receptor blockade on bismuth absorption from three ulcer-healing compounds. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:889–894. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90712-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagstaff AJ, Benfield P, Monk JP. Colloidal bismuth subcitrate. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and its therapeutic use in peptic ulcer disease. Drugs. 1988;36:132–157. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198836020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gorbach SL. Bismuth therapy in gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:863–875. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90983-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gladziwa U, Koltz U. Pharmacokinetic optimisation of the treatment of peptic ulcer in patients with renal failure. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1994;27:393–408. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199427050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Danesh BJ, McLaren M, Russell RI, Lowe GD, Forbes CD. Comparison of the effect of aspirin and choline magnesium trisalicylate on thromboxane biosynthesis in human platelets: role of the acetyl moiety. Haemostasis. 1989;19:169–173. doi: 10.1159/000215911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sweeney JD, Hoernig LA. Hemostatic effects of salsalate in normal subjects and patients with hemophilia A. Thromb Res. 1991;61:23–27. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(91)90165-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kwok CS, Arthur AK, Anibueze CI, Singh S, Cavallazzi R, Loke YK. Risk of Clostridium difficile infection with acid suppressing drugs and antibiotics: meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1011–1019. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eom CS, Jeon CY, Lim JW, Cho EG, Park SM, Lee KS. Use of acid-suppressive drugs and risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2011;183:310–319. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.092129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hess MW, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, Drenth JP. Systematic review: hypomagnesaemia induced by proton pump inhibition. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:405–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu EW, Bauer SR, Bain PA, Bauer DC. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis of 11 international studies. Am J Med. 2011;124:519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Packey CD, Sartor RB. Commensal bacteria, traditional and opportunistic pathogens, dysbiosis and bacterial killing in inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:292–301. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32832a8a5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:577–594. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Naidoo K, Gordon M, Fagbemi AO, Thomas AG, Akobeng AK. Probiotics for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD007443. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007443.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steed H, Macfarlane GT, Blackett KL, Bahrami B, Reynolds N, Walsh SV, Cummings JH, Macfarlane S. Clinical trial: the microbiological and immunological effects of synbiotic consumption - a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study in active Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:872–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Helwig U, Venturi A, Lammers KM, Brigidi P, Vitali B, Poggioli G, Miglioli M, Campieri M. Prophylaxis of pouchitis onset with probiotic therapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1202–1209. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Venturi A, Brigidi P, Matteuzzi D, Bazzocchi G, Poggioli G, Miglioli M, Campieri M. Oral bacteriotherapy as maintenance treatment in patients with chronic pouchitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:305–309. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mimura T, Rizzello F, Helwig U, Poggioli G, Schreiber S, Talbot IC, Nicholls RJ, Gionchetti P, Campieri M, Kamm MA. Once daily high dose probiotic therapy (VSL#3) for maintaining remission in recurrent or refractory pouchitis. Gut. 2004;53:108–114. doi: 10.1136/gut.53.1.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang KY, Li SN, Liu CS, Perng DS, Su YC, Wu DC, Jan CM, Lai CH, Wang TN, Wang WM. Effects of ingesting Lactobacillus- and Bifidobacterium-containing yogurt in subjects with colonized Helicobacter pylori. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:737–741. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Szajewska H, Horvath A, Piwowarczyk A. Meta-analysis: the effects of Saccharomyces boulardii supplementation on Helicobacter pylori eradication rates and side effects during treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1069–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tong JL, Ran ZH, Shen J, Zhang CX, Xiao SD. Meta-analysis: the effect of supplementation with probiotics on eradication rates and adverse events during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:155–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zou J, Dong J, Yu XF. Meta-analysis: the effect of supplementation with lactoferrin on eradication rates and adverse events during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Helicobacter. 2009;14:119–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Borrelli F, Izzo AA. The plant kingdom as a source of anti-ulcer remedies. Phytother Res. 2000;14:581–591. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200012)14:8<581::aid-ptr776>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin J, Huang WW. A systematic review of treating Helicobacter pylori infection with Traditional Chinese Medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4715–4719. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xie JH, Chen YL, Wu QH, Wu J, Su JY, Cao HY, Li YC, Li YS, Liao JB, Lai XP, et al. Gastroprotective and anti-Helicobacter pylori potential of herbal formula HZJW: safety and efficacy assessment. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:119. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu W, Liu Y, Zhang XZ, Li N, Cheng H. In vitro bactericidal activity of Jinghua Weikang Capsule and its individual herb Chenopodium ambrosioides L. against antibiotic-resistant Helicobacter pylori. Chin J Integr Med. 2013;19:54–57. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1248-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kushima H, Nishijima CM, Rodrigues CM, Rinaldo D, Sassá MF, Bauab TM, Stasi LC, Carlos IZ, Brito AR, Vilegas W, et al. Davilla elliptica and Davilla nitida: gastroprotective, anti-inflammatory immunomodulatory and anti-Helicobacter pylori action. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;123:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Calvo TR, Lima ZP, Silva JS, Ballesteros KV, Pellizzon CH, Hiruma-Lima CA, Tamashiro J, Brito AR, Takahira RK, Vilegas W. Constituents and antiulcer effect of Alchornea glandulosa: activation of cell proliferation in gastric mucosa during the healing process. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:451–459. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moleiro FC, Andreo MA, Santos Rde C, Moraes Tde M, Rodrigues CM, Carli CB, Lopes FC, Pellizzon CH, Carlos IZ, Bauab TM, et al. Mouririelliptica: validation of gastroprotective, healing and anti-Helicobacter pylori effects. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;123:359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lemos LM, Martins TB, Tanajura GH, Gazoni VF, Bonaldo J, Strada CL, Silva MG, Dall’oglio EL, de Sousa Júnior PT, Martins DT. Evaluation of antiulcer activity of chromanone fraction from Calophyllum brasiliesnse Camb. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;141:432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sartori NT, Canepelle D, de Sousa PT, Martins DT. Gastroprotective effect from Calophyllum brasiliense Camb. bark on experimental gastric lesions in rats and mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;67:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Souza Mdo C, Beserra AM, Martins DC, Real VV, Santos RA, Rao VS, Silva RM, Martins DT. In vitro and in vivo anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of Calophyllum brasiliense Camb. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;123:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moraes Tde M, Rodrigues CM, Kushima H, Bauab TM, Villegas W, Pellizzon CH, Brito AR, Hiruma-Lima CA. Hancornia speciosa: indications of gastroprotective, healing and anti-Helicobacter pylori actions. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bonamin F, Moraes TM, Kushima H, Silva MA, Rozza AL, Pellizzon CH, Bauab TM, Rocha LR, Vilegas W, Hiruma-Lima CA. Can a Strychnos species be used as antiulcer agent? Ulcer healing action from alkaloid fraction of Strychnos pseudoquina St. Hil. (Loganiaceae) J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;138:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ndip RN, Malange Takang AE, Echakachi CM, Malongue A, Akoachere JF, Ndip LM, Luma HN. In-vitro antimicrobial activity of selected honeys on clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori. Afr Health Sci. 2007;7:228–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Toda M, Okubo S, Ohnishi R, Shimamura T. [Antibacterial and bactericidal activities of Japanese green tea] Nihon Saikingaku Zasshi. 1989;44:669–672. doi: 10.3412/jsb.44.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Toda M, Okubo S, Hara Y, Shimamura T. [Antibacterial and bactericidal activities of tea extracts and catechins against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus] Nihon Saikingaku Zasshi. 1991;46:839–845. doi: 10.3412/jsb.46.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stoicov C, Saffari R, Houghton J. Green tea inhibits Helicobacter growth in vivo and in vitro. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33:473–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ruggiero P, Rossi G, Tombola F, Pancotto L, Lauretti L, Del Giudice G, Zoratti M. Red wine and green tea reduce H pylori- or VacA-induced gastritis in a mouse model. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:349–354. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Takabayashi F, Harada N, Yamada M, Murohisa B, Oguni I. Inhibitory effect of green tea catechins in combination with sucralfate on Helicobacter pylori infection in Mongolian gerbils. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:61–63. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kang H, Rha SY, Oh KW, Nam CM. Green tea consumption and stomach cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol Health. 2010;32:e2010001. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yam TS, Shah S, Hamilton-Miller JM. Microbiological activity of whole and fractionated crude extracts of tea (Camellia sinensis), and of tea components. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;152:169–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Horiba N, Maekawa Y, Ito M, Matsumoto T, Nakamura H. A pilot study of Japanese green tea as a medicament: antibacterial and bactericidal effects. J Endod. 1991;17:122–124. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]