Abstract

Context:

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is an important gender-based, social, and public health problem, affecting women globally.

Aims:

The aim was to report the prevalence of IPV and describe the coping strategies of the victims.

Settings and Design:

It was conducted in the general outpatient clinic of a tertiary care hospital using a cross-sectional design.

Materials and Methods:

A random sample of consenting women living in an intimate partnership for a minimum of 1 year were served with a three part structured questionnaire which sought information on sociodemographic characteristics, the experience of IPV and the Brief COPE Inventory.

Statistical Analysis Used:

SPSS version 17.0 software, Microsoft word and Excel were used in data handling and analysis. Means, percentages, standard deviations, and Chi-square were calculated. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results:

Of the 384 participants, 161 (41.9%) were physically abused. IPV was significantly common among women ≤40 years of age, married couples (78.5%), unemployed and in Christians. It was precipitated by argument with husband (19.25%) and financial demands (44.10%). The employed coping strategy with the highest score was religion. The least score was found in substance abuse.

Conclusion:

There was significantly high prevalence of domestic violence against women in this study. Hence, routine screening is advocated by family physicians to elicit abuse in order to avoid the more devastating psychological consequences after the incidence so as to institute appropriate treatment as multiple episodes of abuse appears to be cumulative in effect. The reason for violence mainly borders around the argument with husband and finance issues. The coping strategies utilized by the participants minimally involve substance abuse, but more of a religion.

Keywords: Domestic violence, Nigeria, outpatient clinic, response strategies

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is an important social and public health problem, affecting women globally. It is a gender-based violence that involves people in intimate relationships and may be perpetrated by either men or women.[1] However, this paper concentrates on IPV by men against women because of its negative effects on women's health. It cuts across nations, cultures, religion, and class.[2,3]

From community-based studies, the lifetime prevalence of IPV ranges from 15% to 71% among women in marriage or current partnerships globally.[4] The reported lifetime prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa ranges from 11% to 52%, respectively.[5] In hospital based studies, prevalence figures recorded among women interviewed in outpatient emergency clinics were 14.6% in the United States,[6] 4% in a population of women attending a gynecology outpatient clinic in the United Kingdom[7] and 87% in Jordan.[8] The prevalence reported from various hospital based studies in Nigeria ranges from 28% in Zaria[9] to 46% in Nnewi.[1] These reported prevalence figures might only be the tip of the iceberg because of under-reporting, lack of standardization of methods[10] and beliefs that issues concerning families and intimate relationships should not be discussed as it is seen as a “private matter.”[11] Apart from the obvious physical injuries resulting from IPV, victims have increased risk of developing long-term negative mental health problems such as posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety.[12,13] Suicide attempts have been used as a way to escape from the abuse in some cultures.[14]

Violence in an intimate relationship is dysfunctional behavior in which the victim has to adopt coping strategies. These consist of cognitive and behavioral efforts adopted to master, reduce, or tolerate the internal and/or external demands that are created by the violence.[15] Though researchers have examined and documented the personal characteristics of the perpetrators or the victims of IPV, negative and long-term effects of IPV on women, yet there is limited information on how women cope with the abuse and violence they experience from intimate partners. Various coping strategies are adapted by different individuals confronted with these negative affective states and associated life problems.[16] Some of these strategies are beneficial for the individual while others, such as substance use, are maladaptive and may result in poorer health outcomes for the patient.[17]

By definition, the family physicians are primary care practitioners who provide continuing, comprehensive care in a personalized manner to patients of all ages, sex and to their families regardless of the presence of disease or the nature of the presenting complaint. By virtue of their ongoing therapeutic relationship with the whole family,[18] they are well positioned to encounter large numbers of victims of IPV in their practice. Despite the high prevalence of IPV in primary care, there is insufficient recognition by family physicians.[19] The two main reasons identified for insufficient recognition of IPV victims include time limitation in primary care practices and lack of professional knowledge.[20] Increasing the knowledge, training, skills and the capacity of physicians on IPV identification and management, remains a pressing gap. Consequently, this study is aimed to report the prevalence of IPV and describe the coping strategies of the victims attending the general outpatient clinic in the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital. This study will aid primary care physicians to identify victims of IPV and offer culturally sensitive and appropriate services to them. It will also aid practitioners to understand the ways women cope on their own and within their own belief systems.

Materials and Methods

Study site

This was carried out at the General Outpatients Department (GOPD) of the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt in the south southern geopolitical zone of Nigeria.

Study design

This is a cross-sectional survey.

Sample size estimation

Using prevalence of 50%, adopted from the Nigerian Demographic and Health Survey report[21] and the formula: n = p (1 − p) q2/d2 for sample size determination,[22] the minimum calculated sample size was 384.

Subjects

The study population consisted of a random sample of all consenting adult women currently living in an intimate partnership for a minimum of 1 year and seeking medical care for whatever reason in the GOPD.

Inclusion criteria

Women aged ≥18 years in intimate partner relationship for at least 1 year.

Women who were willing to participate and gave verbal consent.

Exclusion criteria

Women who were very sick and could not be interviewed.

Women that were accompanied by an intimate partner.

Procedure

A three part structured questionnaire was designed. The first part sought information about the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics such as age, marital status, level of education and religion. The second part was designed based on literature review and information on IPV gathered from informal conversations with women attending the clinic. The experience of the participants on IPV was assessed using the question, “within the past 1 year, have you been hit, slapped, kicked, or otherwise physically hurt by your partner?” Those who gave an affirmative answer to any of the questions were chosen as having experienced IPV. They were further interviewed on the reasons for the action. These parts of the questionnaire were pretested on 30 women and all ambiguities corrected.

The third part consisted of the Brief COPE Inventory.[23] It is the abridged version of the original COPE inventory. The brief COPE scale is a 28-item self-report measure of problem-focused versus emotion-focused coping skills. The scale consists of 14 domains/sub-scales (self-distraction, active coping, denial, substance use, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, behavioral disengagement, venting, positive reframing, planning, humor, acceptance, religion, self-blame) of two items each. It was used to determine the coping strategies employed in the past 1 month by the participants screened as victims of IPV. Participants were asked to respond to each item on a four-point Likert scale, indicating what they generally do following the stress associated with IPV (1 = I have not been doing this at all - 4 = I have been doing this a lot). The scores (ranging from 2 to 8) and the means for each coping method were then calculated. The higher the score on each coping strategy, the greater use of the specific coping strategy. The brief COPE scale has good internal consistency and validity. The questionnaire was administered to consenting women by two nurses who were trained for a period of 1 week for the purpose of this study.

Data analysis

For the purpose of this study, age groups, educational status and occupational groups were collapsed into dichotomous measures to facilitate statistical calculations. The age groups were dichotomized into adolescents and young adults (≤40 years)[24] and older adults (>40 years). Educational status was grouped as ≤secondary education level and tertiary education level and occupation groups into unemployed and employed.

Data handling and analysis were carried out using SPSS 17.0 software, Microsoft word and Excel. Tables were constructed, and parameters such as means, percentages, standard deviations and Chi-square were calculated. P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Ethical clearance

The approval to undertake the study was sought and obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt. Informed consent was sought and received from all the study participants and confidentiality was assured.

Results

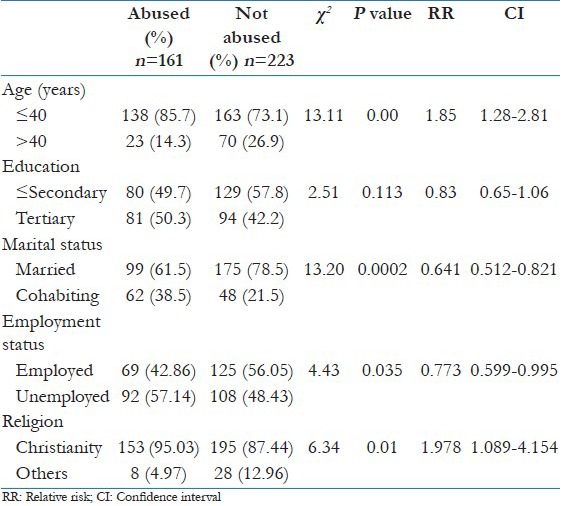

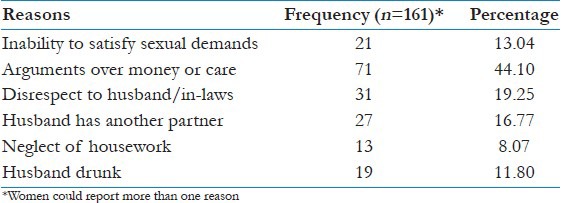

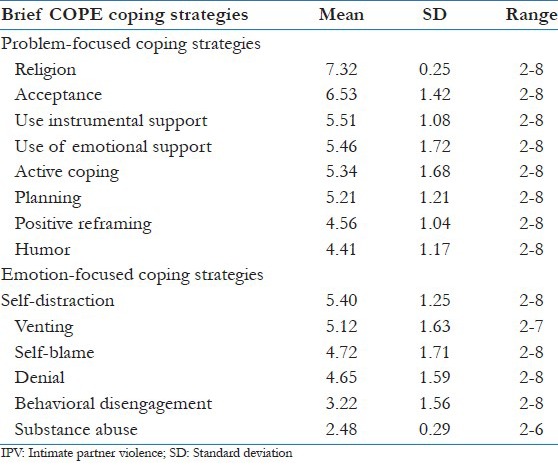

Three hundred and eighty four women with an age range of 18-59 years and a mean age of 31.31 ± 8.61 years were investigated. One hundred and sixty one (41.9%) of the women were physically abused. A significantly high percentage of the physically abused women was ≤40 years of age. They also stand a higher risk of being abused than those over 40 years of age (P = 0.001, relative risk [RR] =1.85, confidence interval [CI] =1.28-2.81). There was a significant association between IPV and marital status. The married couples are less likely to be abused than the cohabiting couples (P = 0.0002, RR = 0.641, CI = 0.512-0.821). IPV was significantly more (57.14%) among the unemployed. They are also more likely to suffer it (P = 0.035, RR = 0.773, CI = 0.599–0.995). The Christians significantly suffered more IPV (95.03%) than the believers of other religious groups. They are also more predisposed to IPV (P = 0.01, RR = 1.978, CI = 1.089-4.154) [Table 1]. The reasons for violence included mainly argument with husband (19.25%) and financial demands (44.10%). The least cause of violence was inadequate attention to children (8.07%) [Table 2]. The used coping strategy with the highest score was religion. The least score was found in substance abuse [Table 3].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of subjects

Table 2.

Reasons given by victims for violence

Table 3.

Brief coping style scores in victims of IPV

Discussion

Ideally, marital relationship should be a complimentarily peaceful and happy coexistence between two people. However, certain circumstances may cause misunderstanding and disharmony in a relationship where there should be no abuse especially physical abuse. Although Nigeria is a party to most of the instruments aimed at eradicating violence against women, such as the Beijing Declaration in 1995,[25] this antisocial behavior continues to be persistent in the country.

The prevalence of IPV in this study is comparable to 46% in Nnewi, South Eastern Nigeria,[2] but higher than 28% in Zaria in North central Nigeria.[10] A very high prevalence of 87% was reported in Jordan, a developing country.[8] Reported prevalence figures from clinics in the developed countries are14.6% in the United States[6] and 4% in the United Kingdom.[7] These are lower than the figures from the developing countries. The high prevalence in this study may be connected with the existence of some weird cultural norms. Beating of wives and children in many developing countries including Nigeria is widely sanctioned as a form of discipline and not a violent behavior.[26] Oyediran and Isiugo-Abanihe in their study reported high level of support expressed for wife beating by both males and females.[21] This is due to the fact that IPV functions as a means of enforcing conformity with the role of a woman within customary society. It is therefore not seen as a criminal offence; moreover, domestic violence may also be perceived as a sign of love in some societies.[27]

The significantly high percentage of the abused women below 40 years could be attributed to a lot of issues in the family life cycle. This period correspond to the launching years when the couple's functions and responsibilities expand especially with the arrival of children. There is associated financial strain with decrease in leisure activities. These younger couples are likely to have lower educational status with concomitant lower income and likely underemployment. These predispose to violence.[28] The resultant stress results in irritability and violence. The younger women are also more likely to have younger partners and these tend to be more violent than older men.[29]

Married women were significantly more battered than the cohabiting women in this study. This finding is surprisingly contrary to what is expected and disagrees with a report by Bachmann.[30] A possible reason for our finding could be the fact that the population of cohabiting women in the study group was small. Another reason is the fact that in Nigeria as in most African settings, a woman surrenders to her husband exclusive sexual rights and obedience on getting married. This invariably gives her husband the liberty to violate and batter her if he feels that she has not adequately fulfilled her obligations, or for any other reason.[21] Cohabitation is a common phenomenon among young people and could be due to the inability of the young men to raise money to marry the women formally. Men may also want to cohabit with the women to make sure they are fertile before paying their bride price. Men and women are likely to cohabit for about 3 years prior to becoming legally married.[31] Violence is more likely to occur among them as found in this study because of the weak bonding between them.[32]

Women without employment were more likely to be abused in this study. This corroborates with other researchers who reported that a significantly higher proportion of domestic violence victims were homemakers without paid employment.[11,33] Employment may reduce women's dependence on their husbands and enhance their power within households and relationships. This may reduce their vulnerability to domestic violence.[34] On the other hand, employed women may be at higher risk of experiencing violence because they may be more likely to challenge their husbands’ authority or because their husbands perceive them as a threat to their authority.[35]

The identified reasons for domestic violence in this study are similar to the findings by Salaudeen et al. in Kano metropolis in Nigeria.[36] It is curious to mention that in this study, the most common reasons given by respondents for violence include arguments over money or care and disrespect to husband/in-laws. Research has highlighted the challenges that men face in meeting their role as economic providers.[37,38] Men who fail to provide economically for their families in some societies are often criticized and humiliated by neighbors.[37] This leads to frustration, stress, marital discord and IPV. On the other hand, women whose husbands are in paid employment are significantly less likely to report physical violence when compared to women with unemployed husbands.[39] It may therefore be necessary to include entrepreneurial studies into the school curriculum so that men could learn to fend for their families in the event of no paid employment. This will improve the economy of the family and minimize the occurrence of IPV.

The significantly high prevalence of IPV among the practitioners of Christian religion in this study is a surprising finding. In the environment of this study, religious involvement often involves members of the immediate and extended family. This may mean that these relationships are actually being strengthened through religious involvement, minimizing the risk not only of domestic violence, but also of other forms of family violence as well.[40] The Christian teaching on love also seems to protect the adherents against abuse. On the other hand, the doctrine of female subordination to male authority appears to encourage domestic violence against women. This may be a reason for the significant association of domestic violence with the Christian religion in this study. The predominant Christian population in the location of this study could also have contributed to this finding.

The benefits of problem-focused coping, such as acceptance, positive reframing, and turning to religion or spirituality have been highlighted by some researchers.[23] In a study of the relationship between spirituality and coping, a positive correlation was identified between the increase in the spirituality of the patients and their psychological wellbeing and functions.[41] An increase in the functioning of religious coping strategy has been found to decrease anxiety, depression, hopelessness and stimulates psychological functions, adaptation to the illness process, life satisfaction, and quality of life in diabetic patients.[41] This study confirmed the findings by the previous researchers. The problem-focused coping strategy with the highest score in this study was religion. The activities in this coping strategy include praying, reading of the Bible and visit to the pastor for counseling and prayers. Other strategies include acceptance, using instrumental support and using emotional support. Among the emotion-focused strategies, the highest scores were found in self-distraction and venting and the lowest score in substance use (use of alcohol or other drugs to feel better or help the individual get through his/her symptoms). The low score in substance abuse is an encouraging finding. A probable explanation for low scores on substance abuse could be the fact that women generally are not known to abuse alcohol when compared to their male counterparts.[42] The restriction of sale of sedatives and hypnotics over the counter in Nigeria could have influenced the use of drugs.

Primary care is an important early intervention site for IPV, because family physicians/general practitioners, who manage these centers, have an ongoing therapeutic relationship with the whole family.[18] Although the family physician by virtue of his training is knowledgeable in communication skills, use of eco map, family APGAR, and patient centered consultation skills, his ability to recognize victims of IPV is poor.[19] This has been attributed to time limitation in primary care practices and lack of professional knowledge.[20] This finding is a source of concern for the profession and suggests there is some urgency in establishing an IPV curriculum to provide physicians with the essential knowledge and skills necessary to increase their comfort levels in identifying and managing victims of IPV.

Globally, training of doctors has been found to be deficient on the emerging demands for IPV. In Nigeria, the challenge is even greater as there are no formal opportunities of undergraduate, postgraduate or continuous education on IPV. Although some medical schools have started expanding their curriculums to include IPV education in some countries,[43] this early training has been frequently shown to be inadequate to address the problem since the effect of training tends to diminish with time.[44] Reinforcement of knowledge acquired during the undergraduate training is therefore very important during family medicine residency training and the mandatory continuous professional development organized by the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria for medical practitioners.

Methodological considerations

This study is not without limitations, as usual to this type of research topic. First, the topic is very sensitive and respondents may be shy to express their views openly, as they may think that their responses may damage the reputation of themselves and their families. Second, like any study based on the self-reporting, there might be recall bias in disclosing the violent episodes. Third, the cross-sectional design itself does not allow for making conclusions focused on associations. It is difficult to make causal inferences. Despite these limitations, the study had methodological strengths including use of standardized pretested questionnaire, inclusion of all groups of population and training given to research nurses to interview the respondents.

Conclusion

The study confirms the high prevalence of domestic violence against women irrespective of age, marital status, employment status and religion. The reason for violence mainly borders around argument with husband and finance issues. The coping strategies utilized by the participants minimally involve substance abuse but more of religion. In light of these findings, family physicians must be trained to assess for IPV as a means of promoting the health status of women. The results of such assessment will provide vital information to appraise the situations, develop interventions as well as policies and programs towards preventing IPV against women.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Johnson MP, Leonne JM. The differential effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence: Findings from the national violence against women survey. Fam Issues. 2005;26:322–49. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ilika AL, Okonkwo PI, Adogu P. Intimate partner violence among women of childbearing age in a primary health care centre in Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2002;6:53–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Dill L, Schroeder AF, DeChant HK, et al. The “battering syndrome”: Prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:737–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C WHO. Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: An observational study. Lancet. 2008;371:1165–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okenwa LE, Lawoko S, Jansson B. Exposure to intimate partner violence amongst women of reproductive age in Lagos, Nigeria: Prevalence and predictors. J Fam Violence. 2009;24:517–30. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dearwater SR, Coben JH, Campbell JC, Nah G, Glass N, McLoughlin E, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner abuse in women treated at community hospital emergency departments. JAMA. 1998;280:433–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.John R, Johnson JK, Kukreja S, Found M, Lindow SW. Domestic violence: Prevalence and association with gynaecological symptoms. BJOG. 2004;111:1128–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Nsour M, Khawaja M, Al-Kayyali G. Domestic violence against women in Jordan: Evidence from health clinics. J Fam Violence. 2009;24:569–79. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ameh N, Kene TS, Onuh SO, Okohue JE, Umeora OU, Anozie OB. Burden of domestic violence amongst infertile women attending infertility clinics in Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2007;16:375–7. doi: 10.4314/njm.v16i4.37342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO/WHD. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. World Report on Violence. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yusuf OB, Arulogun OS, Oladepo O, Olowokeere F. Physical violence among intimate partners in Nigeria: A multi level analysis. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2011;3:240–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvete E, Corral S, Estévez A. Coping as a mediator and moderator between intimate partner violence and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Violence Against Women. 2008;14:886–904. doi: 10.1177/1077801208320907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krause ED, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, Dutton MA. Avoidant coping and PTSD symptoms related to domestic violence exposure: A longitudinal study. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:83–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasan A, Danis R, Tamam L, Ozmen S, Ozkan M. Socio-cultural features and sex profile of the individuals with serious suicide attempts in South Eastern Turkey: A one-year survey. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38:467–80. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller L, Spitz E. Multidimensional assessment of coping: Validation of the Brief COPE among French population. Encephale. 2003;29:507–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasi PM, Kassi M, Khawar T. Excessive work hours of physicians in training: Maladaptive coping strategies. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vosvick M, Koopman C, Gore-Felton C, Thoresen C, Krumboltz J, Spiegel D. Relationship of functional quality of life to strategies for coping with the stress of living with HIV/AIDS. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:51–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ansara DL, Hindin MJ. Formal and informal help-seeking associated with women's and men's experiences of intimate partner violence in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1011–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shefet D, Dascal-Weichhendler H, Rubin O, Pessach N, Itzik D, Benita S, et al. Domestic violence: A national simulation-based educational program to improve physicians’ knowledge, skills and detection rates. Med Teach. 2007;29:e133–8. doi: 10.1080/01421590701452780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selic P. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and related interventions in family medicine: A review with special emphasis on the state of affairs in Slovenia. OA Fam Med. 2013;1:3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oyediran KA, Isiugo-Abanihe U. Perceptions of Nigerian women on domestic violence: Evidence from 2003 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey. Afr J Reprod Health. 2005;9:38–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Araoye MO. Ilorin, Nigeria: Nathadex Publishers; 2003. Research Methodology with Statistics for Health and Social Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: Consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erikson E. Erikson's stages of psychosocial development. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 05]. Available from: http://www.psychology.about.com/library/bl_psychosocial_summary.htm .

- 25.Beijing, China, New York: United Nations; 1995. United Nations. The Fourth World Conference on Women. [Google Scholar]

- 26.UNICEF/FMOH. New York: UNICEF; 2001. Children's and Wome's Rights in Nigeria. A Wake-up Call. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jewkes R, Levin J, Penn-Kekana L. Risk factors for domestic violence: Findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:1603–17. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heise LL. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4:262–90. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burge SK. How do you define abuse? Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:31–2. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachmann R. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 1995. Violence against Woman: Estimates from the Redesigned Survey Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. Publication no. NCJ-145325. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodwin PY, Mosher WD, Chandra A. Marriage and cohabitation in the United States: A statistical portrait based on cycle 6 (2002) of the National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat. 2010;23:1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kenney CT, McLanahan SS. Why are cohabiting relationships more violent than marriages? Demography. 2006;43:127–40. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsui KL, Chan AY, So FL, Kam CW. Risk factors for injury to married women from domestic violence in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2006;12:289–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vyas S, Watts C. How does economic empowerment affect women's risk of intimate partner violence in low and middle income countries?: A systematic review of published evidence. J Int Dev. 2008;21:577–602. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rocca CH, Rathod S, Falle T, Pande RP, Krishnan S. Challenging assumptions about women's empowerment: Social and economic resources and domestic violence among young married women in urban South India. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:577–85. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salaudeen AG, Akande TM, Musa OI, Bamidele JO, Oluwole FA. Assessment of violence against women in Kano metropolis, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2010;17:218–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.George A. Reinventing honorable masculinity-discourses from a working-class Indian community. Men Masc. 2006;9:35–52. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sivaram S, Latkin CA, Solomon S, Celentano DD. HIV prevention in India: Focus on men, alcohol use and social networks. Harvard Health Policy Rev. 2006;7:125–34. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panda P, Agarwal B. Marital violence, human development and women's property status in India. World Dev. 2005;33:823–50. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ellison CG, Trinitapoli JA, Anderson KL, Johnson BR. Race/ethnicity, religious involvement, and domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:1094–112. doi: 10.1177/1077801207308259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowe MM, Allen RG. Spirituality as a means of coping. Am J Health Stud. 2004;19:62–7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brisibe S, Ordinioha B, Dienye PO. Intersection between alcohol abuse and intimate partner's violence in a rural Ijaw community in Bayelsa State, South-South Nigeria. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27:513–22. doi: 10.1177/0886260511421676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moskovic C, Wyatt L, Chirra A, Guiton G, Sachs CJ, Schubmehl H, et al. Intimate partner violence in the medical school curriculum: Approaches and lessons learned. Virtual Mentor. 2009;11:130–6. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2009.11.2.medu2-0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramsay J, Richardson J, Carter YH, Davidson LL, Feder G. Should health professionals screen women for domestic violence? Systematic review. BMJ. 2002:325. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7359.314. 314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]