Abstract

Introduction:

Due to globalization and changes in the health care delivery system, there has been a gradual change in the attitude of the medical community as well as the lay public toward greater acceptance of euthanasia as an option for terminally ill and dying patients. Physicians in developing countries come across situations where such issues are raised with increasing frequency. As euthanasia has gained world-wide prominence, the objectives of our study therefore were to explore the attitude of physicians and chronically ill patients toward euthanasia and related issues. Concomitantly, we wanted to ascertain the frequency of requests for assistance in active euthanasia.

Materials and Methods:

Questionnaire based survey among consenting patients and physicians.

Results:

The majority of our physicians and patients did not support active euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide (EAS), no matter what the circumstances may be P < 0.001. Both opposed to its legalization P < 0.001. Just 15% of physicians reported that they were asked by patients for assistance in dying. Both physicians 29.2% and patients 61.5% were in favor of withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining treatment to a patient with no chances of survival. Among patients no significant differences were observed for age, marital status, or underlying health status.

Conclusions:

A significant percentage of surveyed respondents were against EAS or its legalization. Patient views were primarily determined by religious beliefs rather than the disease severity. More debates on the matter are crucial in the ever-evolving world of clinical medicine.

Keywords: Attitude, euthanasia, legalization, multi-cultural, physician-assisted suicide

Introduction

Advances in medicine, medical technology and its ability to postpone death of a terminally ill patient with its economic ramifications have, led to the controversial issue of euthanasia which has received world-wide attention during recent years. Physicians in developing countries come across situations where such issues are raised with increasing frequency.[1] The issue of euthanasia has been debated all over the world and attempts to legalize it have been defeated most of the times.[2,3] Controversy continues regarding its practice on ethical, moral, social and religious grounds and the debate is made more complex by many forms of euthanasia, which can be interpreted differently. Euthanasia comes from the Greek words eu (good) and thanatos (death), a deliberate act of killing of hopelessly sick or injured individuals in a relatively painless way for reasons of mercy.[4] In active voluntary euthanasia (AVE), the physician takes the patient's life, such as by injecting a lethal substance, while in physician-assisted suicide (PAS), the physician provides the means (e.g. by supplying the lethal dose of a substance) to a patient, who then decides and takes the necessary action to end his own life.[5] The other forms of euthanasia are non-voluntary euthanasia (NVE), when the patient killed is either not capable of making the request or has not done so, such as severely deformed newborn, patients suffering from dementia, or persistent vegetative state[4] and involuntary euthanasia (IVE) which involves killing someone competent, but who has not expressed a wish to die, with the intent of relieving his suffering – which, in effect, amounts to murder.[5] Indirect euthanasia refers to administering opiates or high doses of painkillers that may endanger life, with the primary intention of alleviating pain.[6] This doctrine of double effect is regarded as ethical in most political jurisdictions and by most medical societies. Another, more widely debated, form of euthanasia is passive euthanasia (PE) which involves withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining treatment (LST) either at the request of the patient or when it is considered futile and “allow death” to occur.[7] This has become an established part of medical practice and therefore, cannot really be a form of euthanasia.[4,8,9] However, ambiguities of these terms only confuse public and make them unwilling to accept “do not resuscitate” decision or withdrawing of LST. Physicians also remain guarded about withdrawing LST due to the risk that their actions may be interpreted as intentional killing or murder.

From the physician's perspective, active euthanasia or PAS (EAS) is incompatible with their professional obligation to heal and at the very core, challenges the primary duty of physicians, which is that of saving lives, a position explicitly taken by the American Medical Association and World Medical Association representing the medical profession.[10,11]

At present EAS are illegal in most of the world, but a few countries have passed laws in its favor albeit with strict conditions. Oregon was the only US state that allowed PAS for several years, but states of Washington and Montana have taken steps toward permitting PAS in 2009.[12] Some other countries particularly in Europe have become more flexible in allowing PAS. These differences among countries toward EAS facilitate cross-cultural comparisons toward this complex ethical issue. In Asia the debate is on-going with attempts to legalize it in India and Japan.

Attitude toward EAS are more complicated than simply voicing an opinion in favor of or against it, due to various factors such as culture, religious beliefs, an individual's knowledge about the subject, depression, level of social support, age and gender. Several studies have evaluated the attitudes of health care professionals and the general public toward euthanasia.[13,14,15] Data from these studies show that internationally public opinion tends to favor its legalization more than medical opinion. There is a pressing need for more cross-cultural, international collaborative studies on the subject to explore the differences among countries and the reasons behind these differences. The preferences of chronically ill patients who are directly affected and share the experience of chronic disease, suffering and knowledge of their impending death have seldom been explored. This might make them reflect more on euthanasia. The objectives of our study therefore were to explore the attitude of physicians and chronically ill patients toward euthanasia and related issues. Concomitantly, we wanted to ascertain the frequency of requests for assistance in EAS. Our study has some promise since, it samples a population of patients and physicians who are multi-racial and multi-faith and will add value to the existing results.

Materials and Methods

This questionnaire based survey was conducted in Hospital Tengku Ampuan Afzan (HTAA), Kuantan Pahang, a tertiary care center affiliated to Faculty of Medicine, International Islamic University Malaysia, during 2010-2011. The questions were drawn from the literature used in different studies and modified from comments by members of the research team. The independent variables such as race, religious beliefs and gender were included to determine their influence on the participants’ attitude toward euthanasia. In this survey, euthanasia was defined as “deliberate action undertaken by a physician to end the patient's life at his or her request and with patient's full informed consent in order to relieve his/her pain and suffering.”

Ethics

This study was approved by relevant ethical committees as well as National Institute of Health.

The data among fully conscious adult patients (over 18 years of age) was collected by a clinically experienced and fully trained research assistant who individually approached them in person, during their admission or follow-up consultation in the respective clinics, provided with a brief description of the study and asked for their consent. The patient categories included cancer patients on palliative care, human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), end stage renal failure on chronic hemodialysis, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes with obvious medical complications and stroke victims. The face-to-face patient interview was conducted in privacy to ensure confidentiality. Participation in this study was on voluntary basis using convenience sampling. Consenting patients were given a brief description about the study and EAS, before their views were explored. Each patient was given an identification code and no names or any other personal information was recorded. A structured questionnaire in English or Malay was thus completed by 727 chronically ill patients. The questionnaire had two main sections. The first section composed of eight questions, covered the patient's demographic variables, marital status, education, religion, strength of religious beliefs, status of health and household income. The second section elicited their knowledge and views about EAS. Each question had various responses such as yes/no and agree/disagree depending on the context of the question and most questions could be answered with a tick.

Concurrently, a similar self-reported questionnaire based survey of physicians was conducted, who were approached personally during monthly faculty meetings as well as during annual medical update seminar organized by the Department of Medicine. They were requested to complete the questionnaire at their leisure, if they agreed to participate in the survey. The other physicians were contacted by E-mail. The physician's questionnaire also had two sections. The first section composed of eight items, covered the physician's characteristic, practice variables, religious affiliation and whether they had ever been asked for assistance in active euthanasia. The second section elicited their response toward EAS. The forms were collected again after contacting the respondents. The questionnaire was accompanied by a letter that explained the definition of euthanasia used in this survey, aims of the survey and confidentiality of the information provided and physician's names were not requested.

Data from 922 respondents (727 patients and 195 physicians) thus collected was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-square test was performed to compare the proportions between the physicians and patients and a P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

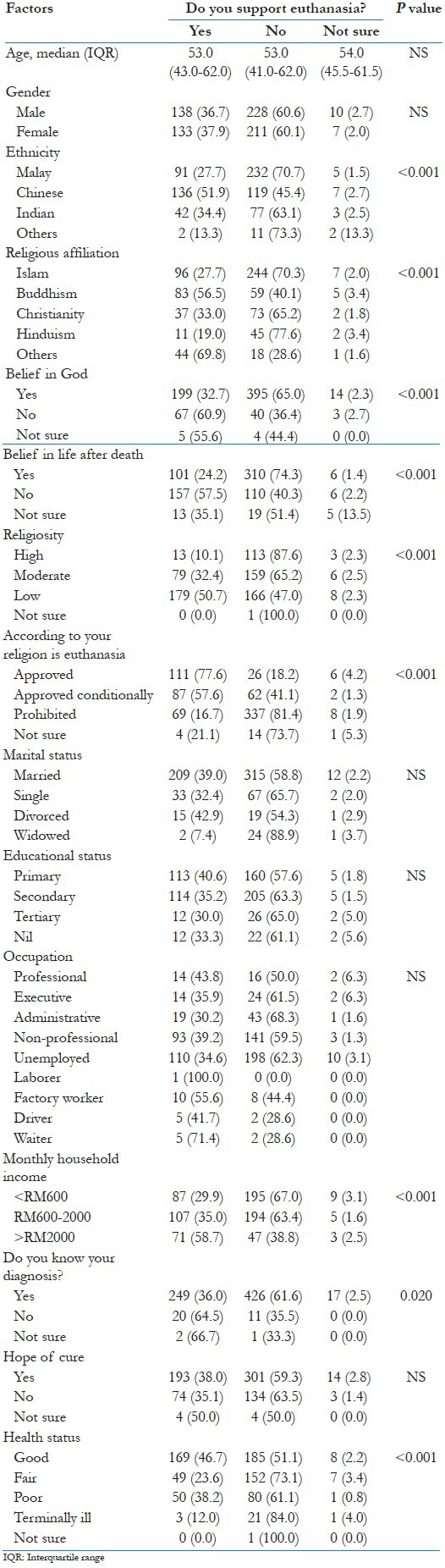

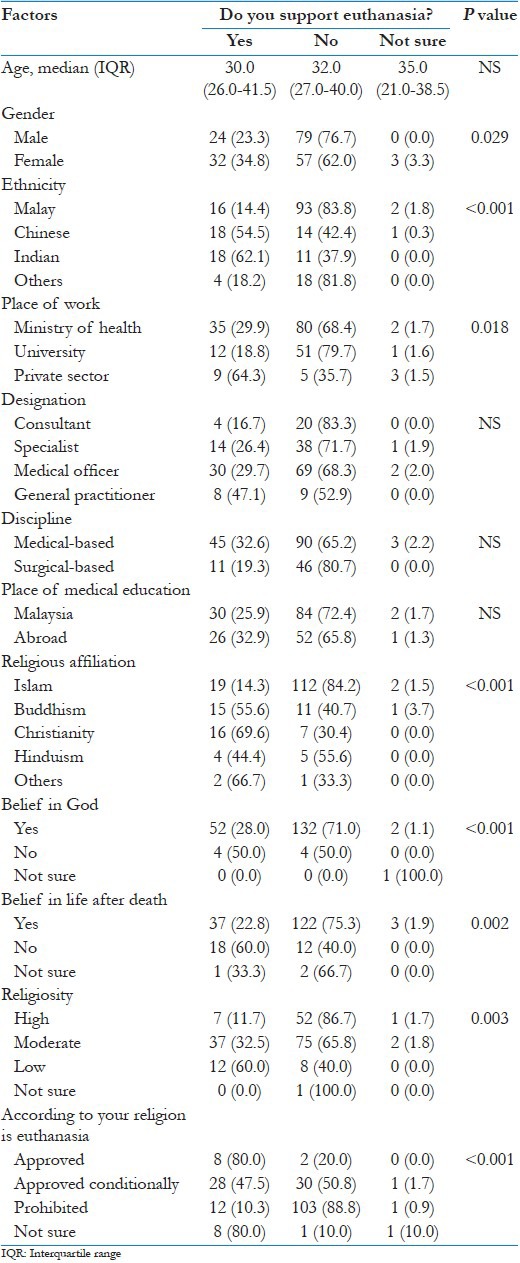

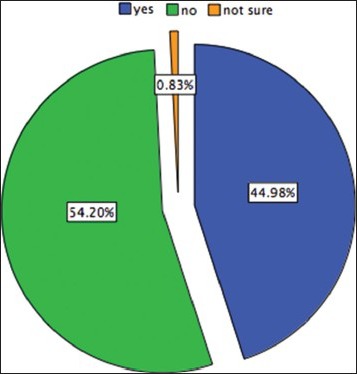

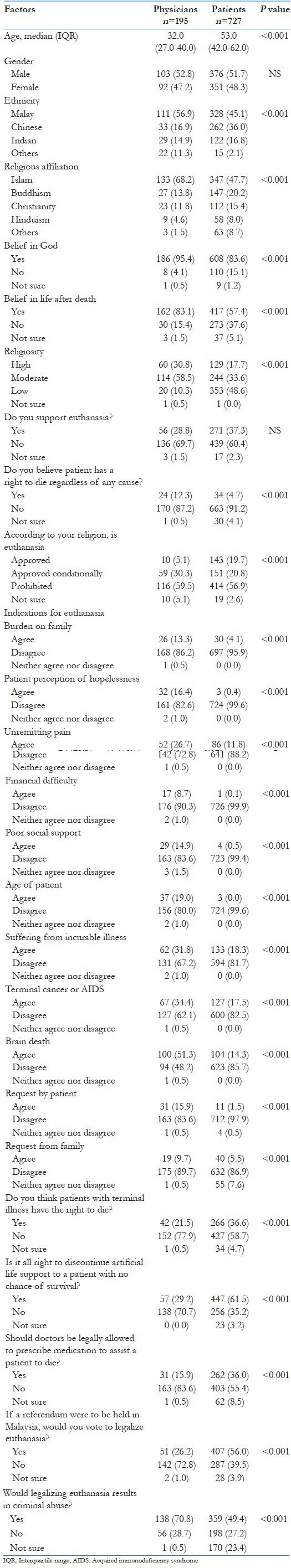

Of the 250 physicians approached in person, 192 completed and returned the questionnaire, yielding a high response rate of 77%. The response through E-mail was very low, only 3 out of 70 responded despite repeated reminders. The overall response rate was therefore 61%. Out of 812 patients approached, 727 responded giving a response rate of 90%. Characteristics of the patient and physician respondents and variables predicting their attitude toward euthanasia are depicted in Tables 1 and 2 respectively. Among responding patients, 73.7% were married, (46.9%) spoke Malay, (44.6%) had completed secondary education, (32.6%) were non-professional and (43.7%) were unemployed. Majority (95.3%) of patients knew their diagnosis, 70% had a hope of cure while 30% knew their condition was incurable. More than half of patients (54.2%) did not know about euthanasia as depicted in Figure 1. Among responding physicians, 60% were working with the Ministry of Health, 32.8% with the university and 7.2% were from the private sector. Majority of respondents were medical officers and more than half (50.8%) were from the internal medicine specialty. Significant proportions of respondents were trained in Malaysia. Physicians’ and patients’ responses compared on individual items are shown in Table 3. Most of the physicians had managed chronically ill patients, but only 30 (15.4%) physicians reported that they had been asked for assistance in dying. Among respondent physicians, more males opted against euthanasia compared with females (P = 0.029). Majority of physicians working in the Ministry of Health were against euthanasia, than those working in the private sector (P = 0.018). There were no significant differences among physicians as per designation or place of medical education (P value of 0.479 and 0.557, respectively). Physicians were significantly younger compared to patients (median [interquartile range]: 32.0 (27.0-40.0) vs. 53.0 (42.0-62.0) years respectively P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in terms of gender between the two groups (P = 0.785).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and variables predicting attitude toward euthanasia (n=727)

Table 2.

Characteristics of physicians and variables predicting attitude toward euthanasia (n=195)

Figure 1.

Patients response: Do you know about Mercy killing/ euthanasia?

Table 3.

Physicians’ and patients’ responses compared on individual items

Attitudes to EAS

The patients in our study were chronically ill with co-morbidities. Nevertheless, we were unable to find a strong relationship between symptom severity and desire for EAS. However, when their views were further explored about issues of unremitting pain, financial difficulty, poor social support and belief that they were a burden on their families, an inclination toward euthanasia was noted. There was no significant difference in terms of education, occupation or marital status. Most of the respondents were believers. Malay physicians opted against euthanasia when compared with Buddhist or Christian physicians. The strongest predictor of unwillingness to EAS was religiosity, those with stronger religious beliefs tended to disapprove AVE < 0.001 [Table 3]. Among physicians 70% and patients 60% opposed EAS, no matter what the circumstances may be. When evaluating the end-of-life issues, 29.2% of physicians and 61% of patients were in favor of withholding or discontinuing LST to a patient with no chances of survival. About 64% of physicians agreed that pain medication should be given to relieve suffering even if it would hasten the patient's death, P < 0.001 and 62% agreed that providing comfort was the primary objective rather than prolonging the life of a terminally ill patient. Majority of patients (91.2%) and physicians (87%) were of the opinion that patients have no right to die regardless of any cause; nor physicians should help a patient to die to relieve his suffering. In response to three hypothetical situations presented, about 16% of the physicians supported active euthanasia while 23% said that they might comply with a request for euthanasia.

Discussion

In western societies “active” euthanasia is the focus of public concern while in Malaysia PE presents more of a dilemma. Dilemmas are expected to intensify as societies become better informed and more complex with conflicting beliefs and values. Our results show that majority of respondents disapproved EAS and opposed its legalization, no matter what the circumstances may be. In other words, having a serious life-threatening illness did not alter their attitude toward the permissibility of EAS. It was not surprising to find that only a small percentage of physicians acknowledged the practice of EAS and that too under restricted conditions. Among patients who supported the idea of EAS were more likely to mention “suffering” in their own definition.

Our research has revealed that religious individuals opposed euthanasia more than those who do not consider themselves religious. Studies reveal religious people and people living in religious countries are more likely to oppose EAS than people living in secular countries.[16,17] Most religions condemn the practice of euthanasia, some strictly so. Malaysia being a multi-faith and multi-cultural country- religious, moral and family values are an integral part of any decision on end-of-life issues. The practice of EAS is illegal and to the best of our knowledge, there is no pro-euthanasia organization at present in the country. When it comes to questions about EAS therefore, there is a tendency to fall back on traditional religious or cultural values pertaining to the sanctity and preservation of life. A well conducted study among nurses from seven countries (Australia, Canada, People's Republic of China, Finland, Israel, Sweden and the US) on AVE in cancer and dementia patients’ revealed opposition by the majority of them.[18] Both our physicians and patients agreed withholding or discontinuing LST to a patient with no chances of survival. Our results were in agreement to other similar studies on the subject.[3,18,19]

Studies have shown that highly educated individuals are less likely to oppose euthanasia than individuals with lower education levels.[20] However in our survey, no such significant difference was noted in terms of education of responding patients. Physicians in our study were significantly younger compared to patients, an unavoidable fact because chronically ill patients will always be old. However, we tested knowledge and practice on the basis of them as physicians and patients by the inclusion criteria, not by age. When the issue was hypothetically explored further, about a sixth of physicians supported euthanasia and a fifth said that they might comply with a request. Hence, there were situations in which our physicians believed that euthanasia was sometimes justifiable and were willing to practice it under such circumstances.

Advocates of EAS argue that people have a right to make their own decisions regarding death and patient autonomy is used as a main argument. Autonomy is important in the decision-making process if patients are able to understand and make intelligent decisions. It is never certain that a patient can voluntarily consent to death. Our groups of patients were chronically ill with co-morbidities, but we were unable to find a strong relationship between symptom severity and desire for EAS. Majority of our respondents were of the opinion that patients have no right to die regardless of any cause; nor should physicians help patients to die, to relieve their suffering. Elderly people may request for EAS due to depression, hopelessness and other related symptoms.[21] This desire frequently changes over time, with appropriate treatment and social support.[21,22,23] EAS is not primarily an individual issue; rather a societal one. Hence, it would be morally justifiable for physicians to apply guided paternalism and prevent them from harm under the principle of beneficence and non-malfeasance. Selecting comfort and dignity is not about giving up; but shifting from cure to care.

Both our physicians and patients opposed to legalization of EAS, as legitimate concerns exist about its potential abuse. In all jurisdictions where EAS is allowed, despite laws and safeguards against its abuse, guidelines are frequently ignored and people have been euthanized without consent or without being terminally ill and transgressors were not prosecuted.[24] According to an Indian study among elderly people, about 61.5% supported euthanasia, but expressed concern that it might be misused as a means of getting rid of invalid elderly persons and avoiding the responsibility of caring for them.[25] Legalization of EAS through referendums may lead to potential social consequences. This may include what is termed by many scholars as the “slippery slope phenomenon,” which suggests that if EAS is legalized, then physicians may also engage in IVE and NVE. It may involve the killing of those who are mentally ill, a burden to society or the health system, AIDS and cancer patients and even children and newborn with disabilities, as suggested in two Netherland studies.[24] It will ultimately undermine medical care and violate the social contract the profession has with the society.

With the economic reality that exists in most third world countries, physicians are caught by the divide between what they ought to do and what they can do. In a study of physicians who worked in two neonatal clinics in India, physicians disagreed among themselves whether parents of seriously ill new born should be involved in decisions about withdrawal of LST from their children. Due to poverty and low levels of education, parents often accept whatever the physician recommends.[26] Further individuals may request for EAS as medical treatment at the end-of-life becomes more than ever expensive.

Under current prevailing conditions the practice of medicine must not be guided by economic and political forces, but by ethics that is internal to the medicine. It entrusts and obligates the physicians to do what is the best for the patient by caring, compassion and comfort, which they need and deserve. In terminally ill patients, physicians must share all aspects of the illness with the family so that inappropriate interventions are avoided and palliative care, focused on relieving symptoms is provided.[27] This may be carried out at home or in an institution, as the case warrants. The term “PE” is misleading and ambiguous term, which causes much confusion and anxiety both in general public and among physicians. We need to introduce community education programs to enhance the public's awareness about end-of-life issues and distinguish between euthanasia and withholding or discontinuing of futile life-prolonging treatments.

The strength of our study lies in our patient selection that included only patients with long-standing chronic illnesses and all of them were mentally alert and able to answer the questionnaire. There are some limitations which need to be mentioned. Although, the data was collected from Kuantan, Pahang only, it may not be reflective of the prevalent clinical practice in the whole of Malaysia. Measurement on religiosity was highly subjective, which needs careful consideration with regard to its interpretation. Finally, opinions may not necessarily predict behaviors.

Conclusion

The findings of our survey indicate that majority of respondents were against EAS and its legalization. Religion was recognized as an important variable against EAS. Our results serve as a background to the current debate on euthanasia in end-of-life care. More research on the matter is needed periodically to document the wishes of chronically ill and suffering patients and medical professionals working closely with them, as restructuring continues.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by research management center, International Islamic University Malaysia (EWD B 0905-279). The authors would like to thank Dato Dr. Sapari Satwi, head Department of Medicine, HTAA for his strong support and allowing us to conduct this survey.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was funded by research management center International Islamic University Malaysia (EWD B 0905.279).

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Abbas SQ, Abbas Z, Macaden S. Attitudes towards euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among Pakistani and Indian doctors: A survey. Indian J Palliat Care. 2008;14:71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snyder L, Sulmasy DP. Physician-assisted suicide. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:209–2016. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-3-200108070-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keown J. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2002. Euthanasia, Ethics and Public Policy: An Argument against Legalization. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartels L, Otlowski M. A right to die? Euthanasia and the law in Australia. J Law Med. 2010;17:532–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman L, Schafer AI. Goldman's Cecil Medicine. 23rd ed. Ch. 2. USA: Saunders; 2008. Bioethics in the practice of medicine; pp. 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norval D, Gwyther E. Ethical decisions in end-of-life care. CME. 2003;21:267–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh D, Caraceni AT, Fainsinger R, Foley K, Glare P, Goh C, et al. 1st ed. Ch. 22. Canada: Saunders; 2009. Palliative medicine. Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide; pp. 110–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warnock M, Macdonald E. Easeful Death. 1st ed. USA: Oxford University Press; 2008. Is there a case for assisted dying; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrard E, Wilkinson S. Passive euthanasia. J Med Ethics. 2005;31:64–8. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.005777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Medical Association 1996. Openion 2.211: Physician assisted suicide. [Last accessed on 2013 May 18]. Available from: http://www.ama.assn.org/ama/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/openion2211page .

- 11.World Medical Association. WMA Statement on Physician-Assisted Suicide. 2005. May, [Last accessed on 2013 Feb 15]. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/p13/index.html .

- 12.Yardley W. First death for Washington assisted-suicide law. New York Times. 2009. May 22, [Last accessed on 2013 Feb 25]. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/23/us/23suicide.html .

- 13.Seale C. Legalisation of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide: Survey of doctors’ attitudes. Palliat Med. 2009;23:205–12. doi: 10.1177/0269216308102041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patelarou E, Vardavas CI, Fioraki I, Alegakis T, Dafermou M, Ntzilepi P. Euthanasia in Greece: Greek nurses’ involvement and beliefs. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2009;15:242–8. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2009.15.5.42350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inghelbrecht E, Bilsen J, Mortier F, Deliens L. Nurses’ attitudes towards end-of-life decisions in medical practice: A nationwide study in Flanders, Belgium. Palliat Med. 2009;23:649–58. doi: 10.1177/0269216309106810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeCesare MA. Public attitudes toward euthanasia and suicide for terminally ill persons: 1977 and 1996. Soc Biol. 2000;47:264–76. doi: 10.1080/19485565.2000.9989022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moulton BE, Hill TD, Burdette A. Religion and trends in Euthanasia attitudes among US adults, 1977-2004. Sociol Forum. 2006;21:249–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis AJ, Davidson B, Hirschfield M, Lauri S, Lin JY, Norberg A, et al. An international perspective of active euthanasia: Attitudes of nurses in seven countries. Int J Nurs Stud. 1993;30:301–10. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(93)90102-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rydvall A, Lynöe N. Withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment: A comparative study of the ethical reasoning of physicians and the general public. Crit Care. 2008;12:R13. doi: 10.1186/cc6786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verbakel E, Jaspers E. A comparative study on permissiveness toward Euthanasia: Religiosity, slippery slope, autonomy, and death with dignity. Public Opin Q. 2010;74:109–39. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson KG, Scott JF, Graham ID, Kozak JF, Chater S, Viola RA, et al. Attitudes of terminally ill patients toward euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2454–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.16.2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blank K, Robison J, Doherty E, Prigerson H, Duffy J, Schwartz HI. Life-sustaining treatment and assisted death choices in depressed older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:153–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Emanuel LL. Attitudes and desires related to euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among terminally ill patients and their caregivers. JAMA. 2000;284:2460–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereira J. Legalizing euthanasia or assisted suicide: the illusion of safeguards and controls. [Last accessed on 2012 Feb 25];Curr Oncol. 2011 18:e38–45. doi: 10.3747/co.v18i2.883. Available from: http://www.current-oncology.com/index.php/oncology/article/view . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sueela M. Elderly's attitude towards death and the concept of euthanasia. Nimhans J. 1998;16:43–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miljeteig I, Norheim OF. My job is to keep him alive, but what about his brother and sister? How Indian doctors experience ethical dilemmas in neonatal medicine. Dev World Bioeth. 2006;6:23–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2006.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens LM, Lynm C, Glass RM. JAMA patient page. Palliative care. JAMA. 2006;296:1428. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.11.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]