Abstract

Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approaches stress the importance of building strong, cohesive collaborations between academic researchers and partnering communities; yet there is minimal research examining the actual quality of CBPR partnerships. The objective of the present paper is to describe and explore the quality of collaborative relationships across the first two years of the Healing of the Canoe project teams, comprised of researchers from the University of Washington and community partners from the Suquamish Tribe. Three quantitative/qualitative process measures were used to assess perceptions regarding collaborative processes and aspects of meeting effectiveness. Staff meetings were primarily viewed as cohesive, with clear agendas and shared communication. Collaborative processes were perceived as generally positive, with Tribal empowerment rated as especially important. Additionally, effective leadership and flexibility were highly rated while a need for a stronger community voice in decision-making was noted. Steady improvements were found in terms of trust between research teams, and both research teams reported a need for more intra-team project- and social-focused interaction. Overall, this data reveals a solid CBPR collaboration that is making effective strides in fostering a climate of respect, trust, and open communication between research partners.

Keywords: Community Based Participatory Research, American Indian/Alaska Native, Tribal Participatory Research, Process Measures, Healing of the Canoe, Research Partnership(s)

INTRODUCTION

Until recently most research focusing on American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) people and communities was conducted by researchers from academic institutions. These researchers were often “outsiders”; in other words they were not familiar with the community/participants under study nor did they spend time in the community or attend to important cultural differences. This generally resulted in studies with questionable findings (J.P. Gone, 2006) that had little or no benefit to the participants or their communities and, unfortunately, often resulted in harms of omission (for example, study findings were never shared with participating communities) or outright harms (Foulks, 1989; Hodge, 2012). In addition, such research practices sometimes led to interventions and practices that were not effective or acceptable to AIAN communities (Caldwell et al., 2005; Joseph P. Gone & Calf Looking, 2011; Wexler, 2011). Equally troubling, little attention was paid to the diversity of AIAN people and communities. With over 565 distinct federally recognized Tribes, many more unrecognized Tribes, and noting that approximately 60% of Native people live off reservations/in urban areas, while some generalizations are possible, it is critical that researchers be aware of the unique histories, belief systems, and current sociopolitical contexts of AIAN communities and use caution in generalizing results to the AIAN population at large (J.P. Gone & Trimble, 2012; Whitbeck, 2006).

Fortunately, the use of Community Based Participatory/Tribal Participatory Research approaches has dramatically improved the rigor and effectiveness of research with AIAN communities (Arviso et al., 2012; Christopher, 2005; Christopher et al., 2011; Lane & Simmons, 2011; LaVeaux & Christopher, 2009; Mohatt, Hazel, et al., 2004; Mohatt, Rasmus, et al., 2004; Thomas, Rosa, Forcehimes, & Donovan, 2011). True CBPR/TPR research partnerships require equitable distribution of power and decision making from determining the research question to appropriate analyses, interpretation, and dissemination of findings. In addition, when working with federally recognized Tribes, attention must be paid to the role of sovereignty including data ownership, use and sharing (Harding et al., 2012; Thomas, Rosa, et al., 2011). Because of the history of research abuses, and consistent with CBPR/TPR principles, the importance of respect, equity, trust, relationship, and collaboration is underscored. Many researchers who work in collaboration with AIAN communities have emphasized the importance of these values in their research partnerships (Burhansstipanov, Christopher, & Schumacher, 2005; Christopher, Watts, McCormick, & Young, 2008; Santiago-Rivera, Morse, & Hunt, 1998; Thomas, Donovan, Sigo, & Price, 2011). Recently, attention has turned to the role of community engagement and the research partnership in the research process. Although relatively sparse, the literature indicates that research partnerships are multi-dimensional, complex, related to research outcomes, and changing over time (Brodsky et al., 2004; Khodyakov et al., 2012). Increasingly, evidence indicates that the quality of the CBPR/TPR research partnership is important for the success of the project.

Community Based Participatory/Tribal Participatory Research approaches stress the importance of building strong, cohesive collaborations between academic researchers and partnering communities; yet there is minimal research examining the actual quality of CBPR partnerships. The Healing of the Canoe project1 (HOC), described below, is firmly guided by the CBPR/TPR framework and has been recognized nationally as an example for its application of the principles of community engagement (Duffy, Aguilar-Gaxiola, McCloskey, Ziegahn, & Silberberg, 2011). HOC project goals were not only to identify and prioritize behavioral health disparities of concern to the community, but also to build relationship and trust between the collaborative partners. It would be disingenuous to espouse the CBPR/TPR philosophy without actually investigating the working relationship between partners; we have made such inquiry a key priority and the results are described in this paper including a discussion section primarily authored by the community partners.

BACKGROUND

Healing of the Canoe: The Community Pulling Together

The Healing of the Canoe project (HOC: http://healingofthecanoe.org) is a collaborative effort between the University of Washington Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute (ADAI) and two federally recognized Tribes, the Suquamish Tribe (ST) and a second Tribe, both located in western Washington State. The second Tribe was not a partner in Phase I of the HOC project and therefore will not be named in this paper; we focus only on the partnership and project with the Suquamish Tribe1 during the first two years of the project.

HOC has used a CBPR/TPR approach from the inception of the partnership. It is important to note that the second author, who is Alaska Native, was known to the Suquamish community for a number of years prior to the research project. The Suquamish Wellness Program was aware of work that she had done previously (LaMarr & Marlatt, 2005) and invited her to meet with them to discuss a potential research project to prevent youth substance abuse and promote good health in a community based and culturally grounded manner. This provided the opportunity for her to serve in the role as “facilitator” from the beginning, one of the core principles of CBPR/TPR which facilitates a balance of power and to assist in translation between researchers (academic institutions) and community members (Tribes in this case). Formal permission to develop a partnership to seek funding was obtained from the Suquamish Tribal Council via a Tribal Resolution and the team was directed to work with the Suquamish Cultural Co-op as the Community Advisory Board. The Suquamish Cultural Co-op is formally charged by the Tribal Council to review and monitor any projects or activities with tribal members that include culture to ensure that they are consistent with Suquamish tribal values and practices. To ensure equity and true partnership, the team co-crafted a grant application, with a Suquamish tribal member as a co-investigator and the principal investigator of the subcontract to the Tribe; the application was successfully funded. The team moved forward with a commitment to work in partnership to plan, implement and evaluate a culturally grounded intervention to reduce health disparities and promote health with a focus on the youth. Through an in-depth community needs/strengths assessment, the Tribe identified youth substance abuse and the need for a sense of cultural belonging among youth as primary issues of community concern and their Elders, youth, and culture as their strengths and resources to address these issues. For a more thorough description of this phase see Thomas, et al, 2009 & 2010, which are co-authored by university and community partners (Thomas, Donovan, & Sigo, 2010; Thomas et al., 2009).

Based on the results of the needs/resources assessment, a focus was placed on developing a culturally relevant intervention. The HOC team reviewed a number of AIAN programs and “best practices” and selected the prevention program “Canoe Journey/Life’s Journey: Life Skills Manual for At-Risk Native Youth” (LaMarr & Marlatt, 2005) developed by members of a UW research team and the Seattle Indian Health Board for use with American Indian/Alaska Native youth in urban settings. This manual was based on the traditional Coastal Salish canoe journey (Neel, 1995), and was adapted for use with the Suquamish community as a tribally specific, culturally tailored prevention program. Members of the ADAI and Suquamish research teams met weekly over the course of a few months with a curriculum development team composed of Suquamish Elders and community members. These meetings were open to all community members and were held immediately after the Elder’s Lunch to allow Elders to participate. This process resulted in a cognitive-behavioral life skills curriculum for tribal youth based on the metaphor of the canoe journey that incorporates Suquamish beliefs, values, traditions, practices, stories and history. Suquamish Elders named this adapted manual “Holding Up Our Youth”.

Regular HOC project meetings were held as follows: the Suquamish Research Team met (at least) weekly and the second author attended these meetings as well; the ADAI team met bi-weekly; and the entire combined team met monthly. The all-team meeting rotated location with one meeting held at the university and the next held in the Suquamish community. Chairmanship of each meeting was also rotated to share leadership roles. Regular community meetings were held to provide updates on the project and receive feedback and suggestions. We served food and gave formal and informal presentations and provided a number of mechanisms for community members to share thoughts, concerns, gratitude, etc. We also provided brief project updates in the monthly Suquamish tribal newsletter. This allowed us to better serve the community and also to be held accountable. Elders are a respected and revered part of the Suquamish community; therefore we also provided formal and informal updates and presentations to them during Elders Lunch.

In addition to these project activities, we committed to bi-directional training and capacity building. Suquamish team members as well as community members were provided training in research methods; the ADAI team was provided with cultural training to increase cultural knowledge, sensitivity, and humility. We also found it necessary to provide training to various university departments with regard to Tribal sovereignty and cultural sensitivity. This ongoing training process resulted in better communication and shared knowledge. The second and fourth authors also served as cultural facilitators, or a “bridge” between the community and the university, which helped with navigating the necessary processes needed to move forward with the project.

It is important to note that in addition to these formal project activities, ADAI committed to informal time spent in the community as well. All ADAI team members have spent time attending community meetings, cultural events, etc., and have volunteered to help prepare and serve meals in Suquamish during the annual Tribal Journey. In addition, the second author attended many additional community events as well as Elders Lunch on a weekly basis. This allowed time for the research team to get to know and better understand the community and, equally important, allowed community members to meet and develop a relationship with the university team. This kind of “face time” supports and nurtures the research partnership as well.

METHODS

Procedure

The majority of data described in this paper are drawn from three primarily quantitative process-related measures administered to both university and Tribal team members of the HOC project staff. The measures were administered at the end of regularly scheduled all-team monthly meetings and, in most cases, turned in anonymously to the Research Coordinator. Two of the questionnaires, Individual Perceptions of the Collaborative Process (IP) (Taylor-Powell, Rossing, & Geran, 1998) and the Meeting Effectiveness Inventory (MEI) (Goodman, Wandersman, Chinman, Imm, & Morrissey, 1996) were administered at each meeting (meetings occurred approximately once a month) and, because it is longer and more involved, the Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory (WCFI) (Mattessich, Murray-Close, & Monsey, 2001) was administered less often (about once every three months). Both the quantitative and qualitative data from measures completed by ADAI or Suquamish core project team members are included in the present analyses.

Measures

Three quantitative process measures were used to assess perceptions regarding collaborative processes and aspects of meeting effectiveness across time. Table 1 presents an overview of the process measure administration and contents.

Table 1. General Information for Individual Perceptions, Wilder, and Meeting Effectiveness Measures.

| Questionnaire | Citation | Total Items |

Response Choices |

Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

|

Individual

Perceptions of the Collaborative Process |

Lonczak, 2006, adapted from Taylor-Powell, E., Rossing, B., Geran, J. 1998 |

16 | Range from 1- 5 (Infrequently; Sometimes; All of the Time) |

12 with 1-5 Range. 3 Open-ended (assess Project Impact; Possible Improvements; and Ways to Do Differently in the Future). 1 with 1-4 Range indicating degree of benefit to community (not for UW staff). The following open-ended question was added the first 12 questions: “If you answered 1 or 2 above, could you please elaborate and let us know how we might improve?” |

|

| ||||

|

Wilder

Collaborative Factors Inventory |

Mattessich, Murray-Close and Monsey, 2001 | 40* | Range from 1 - 5 (Strongly Disagree; Disagree; Neutral, No Opinion; Agree; Strongly Agree) |

The following open-ended question was added to all 19 items (sub-categories): “If you answered 1 or 2 above, could you please elaborate on your thoughts and/or suggestions?” |

|

| ||||

|

Meeting

Effectiveness Inventory |

Goodman, Wandersman, Chinman, Imm, Morrisey, 1996 | 11 | Range from 1 - 5 (Poor; Fair; Satisfactory; Good; Excellent) Includes question- specific examples for extreme ends of scale. |

8 with 1-5 Range; Others assess meeting chair, balance of leadership, and meeting conflict. Spaces for comments are provided. |

40 Individual Questions; 19 Items after sub-category questions were combined

The Individual Perceptions of the Collaborative Process (IP) survey is a 12-item instrument that focuses primarily on one’s personal role in the collaboration. The IP was adapted from the Community Group Member Survey (Taylor-Powell, et al., 1998) in order to fit the specific needs of the HOC project; it was chosen for the present study as one of the few measures available to assess the collaborative processes. Likert response choices range from 1 (Infrequently) through 5 (All the Time), with three additional open-ended questions designed to assess project impact and areas for improvement in the collaborative process. The items of the IP are found in Table 2.

Table 2. Individual Perceptions Survey: Overall Descriptive Statistics.

| Scale Item | Mean (Sd) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | My viewpoint is heard | 4.70 (.55) |

| 2 | I feel comfortable in the group | 4.49 (.69) |

| 3 | I am satisfied with the group’s progress | 4.17 (.53) |

| 4 | I feel there is good communication and respect between community and university collaborators |

4.62 (.57) |

| 5 | I have felt comfortable participating in group meetings and discussions |

4.58 (.63) |

| 6 | I feel that group meetings are productive | 4.35 (.51) |

| 7 | I am viewed as a valued member of the group | 4.56 (.63) |

| 8 | I am satisfied with the frequency of group meetings | 4.18 (.66) |

| 9 | I feel like my opinions have an effect on group decision- making |

4.48 (.65) |

| 10 | I am satisfied with the degree of community participation in the project |

4.01 (.69) |

| 11 | I feel trusting of both community and research collaborators | 4.48 (.63) |

| 12 | I am satisfied about the degree of community impact on project processes |

4.06 (.65) |

Scores range from 1 (Infrequently) to 5 (All of the time)

The Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory (WCFI) (Mattessich, et al., 2001) contains 40 questions that focus on many aspects of the collaborative process, with response choices again ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) through 5 (Strongly Agree). This measure was chosen because it has been used in a number of evaluations of community coalitions, since it provides indicators of the quality of coalition formation, researcher-community partnerships, and successful collaboration factors such as formalization of rules/procedures, leadership style, member participation, membership diversity, agency collaboration, and group cohesion (Zakocs & Edwards, 2006), and because it has been used across time to assess change in such dimensions (Ziff et al., 2010). Items are grouped into categories of factors associated with the collaborative process (e.g. “History of collaboration or cooperation in the community;” “Ability to compromise;” and “Mutual respect, understanding, and trust”). In order to better guide analysis and interpretation, questions were summed and averaged for each category, creating a reduced number of 19 total scale items. These categories are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory: Overall Descriptive Statistics.

| Collaborative factors | Mean (Sd) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Favorable political and social climate | 4.64 (.47) |

| 2 | Mutual respect, understanding, and trust | 4.14 (.58) |

| 3 | Appropriate cross section of members | 3.51 (.83) |

| 4 | Members share a stake in both process and outcome | 4.35 (.62) |

| 5 | Multiple layers of participation | 3.53 (.68) |

| 6 | Flexibility | 4.62 (.51) |

| 7 | Development of clear roles and policy guidelines | 3.98 (.57) |

| 8 | Adaptability | 4.25 (.53) |

| 9 | Appropriate pace of development | 3.83 (.68) |

| 10 | Open and frequent communication | 4.30 (.52) |

| 11 | Established informal relationships and communication links |

4.50 (.56) |

| 12 | Concrete, attainable goals and objectives | 4.46 (.42) |

| 13 | Shared vision | 4.57 (.48) |

| 14 | Unique purpose | 4.57 (.60) |

| 15 | Sufficient funds, staff, materials, and time | 4.03 (.63) |

| 16 | Collaborative group seen as a legitimate leader in the community |

3.95 (.59) |

| 17 | Members see collaboration as in their self-interest | 4.57 (.57) |

| 18 | Ability to compromise | 4.32 (.61) |

| 19 | Skilled leadership | 4.76 (.44) |

Scores range from 1 (Infrequently) to 5 (All of the time)

The Meeting Effectiveness Inventory (MEI) is a relatively brief measure consisting of 8 questions that evaluate work group and coalition meeting effectiveness and productivity adapted from the work of Goodman and colleagues (Goodman, et al., 1996). Given that much of the work between the university and tribal teams took place in the context of regularly scheduled meetings, it was felt important to have a measure of the perceived value of these meetings and to provide corrective feedback across time. The 8 items of the scale focus on various aspects of these team meetings (e.g., productivity, leadership, decision-making, etc.). Response choices ranged from 1 (Poor) through 5 (Excellent) on a Likert scale. The items included on the MEI are found in Table 4.

Table 4. MEI Scale: Overall Descriptive Statistics.

| Scale Item | Mean (Sd) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Clarity of goals for meeting | 4.5 (.532) |

| 2 | General level of participation in the meeting | 4.5 (.558) |

| 3 | Leadership during the meeting | 4.3 (.578) |

| 4 | Balance of leadership between chairperson and staff member | 3.6 (.769) |

| 5 | Quality of decision-making | 4.3 (.583) |

| 6 | Cohesiveness among meeting participants | 4.7 (.498) |

| 7 | Organization of meeting | 4.3 (.603) |

| 8 | Productivity of the meeting | 4.2 (.516) |

Scores range from 1 (Poor) to 5 (Excellent)

Both the WCFI and the MEI were adapted by providing a comment space for each question, thus allowing individuals to provide additional information and/or feedback. This provided qualitative information in addition to the quantitative scores on each of these measures.

Participants

As this is specifically a process-focused paper, participants are exclusively the project staff involved in the first two years of the project. Because of the natural course of staff hiring and turnover during the early years of the project, the number of participants is estimated. Over the course of the two-year time period, four ADAI project staff (the study PI, Project Director and Co-Investigator, Research Analyst, and Research Coordinator) and two Suquamish staff members (the Tribal Co-Investigator and the Tribal Peer Youth Educator) were involved in the project for the entirety of the time period; three additional core Suquamish staff members (Youth Liaison/Facilitators) came and went over the two-year period. Overall, 4 ADAI and 5 Suquamish team members contributed process data, although there is fluctuation in these numbers at any given time. In the case of both the MEI and IP Survey, between 2 and 7 (mean = 5) staff members completed surveys at each meeting over the course of 15 meetings (from 10/2006 to 6/2008). For the WCFI there is less data because it was administered only quarterly. The time-span for the WCFI is the same, as is the range of respondents per meeting (2 to 7); the average number of completed surveys per meetings is however slightly lower (4.2). There is more completed data for the ADAI team for all measures (e.g., 48 IP surveys for ADAI and 23 for Suquamish) because, during the first two study years, there was simply a consistently larger ADAI staff, and more regular attendance by ADAI staff members at team meetings

Analysis

To examine differences between the first two project years, process data were compared between Time 1 (10/2006 – 6/2007) and Time 2 (9/2007 – 6/2008). This comparison was only conducted for the MEI and the IP, as the WCFI was not administered frequently enough to allow it. For these comparative analyses, IP data are available for 7 meetings during Time 1, and 9 meetings during Time 2; MEI data are available for 8 meetings during Time 1, and 7 meetings during Time 2.

Differences in IP and WI responses were also compared between the two research groups: Suquamish Research Team (SRT) and the ADAI Research Team (ART). As noted, more process data are available for ART versus SRT staff because the former research team was larger. Qualitative process data were analyzed by careful and repeated investigation of themes and patterns. From such investigation, constructs were identified and then checked, modified, and ultimately approved by all members of the research team before continued analysis.

An essential caveat concerns the importance of respecting confidentiality in a CBPR-based study, despite potential methodological ramifications. In tribal communities, where many or most community members are at least minimally acquainted and word can travel quickly from person-to-person, failure of tribally-approved research teams to protect participant (including project staff member) confidentiality can potentially have negative consequences at the individual, familial, and community levels (Foulks, 1989). As such, these well-justified concerns regarding research confidentiality within tribal communities are common (Davis & Reid, 1999; Fisher & Ball, 2002), and the present study represents no exception. During the HOC project’s early days, tribal partners were not comfortable with the notion of linking SRT members’ identifiers (e.g., names, key demographic information, or study identification numbers) with process data. This consequent inability to assess which specific team members were present across meetings precludes the ability to adjust for nested data. Therefore, the present data are descriptive in nature. Notably, when a balancing act between issues of confidentiality and data quality exists during CBPR-based research, the importance of confidentiality takes precedence. Once trust between the two teams has been earned, more opportunities may be negotiated. Such is the case in the present HOC Phase 2 project, where a confidential participant coding system was subsequently devised, thereby enabling a more thorough, informative method of analysis with the ability to address key questions posed by the tribal community itself.

RESULTS

Quantitative Questionnaire Findings

Individual Perceptions of the Collaborative Process

Overall, responses on the IP survey’s 1 - 5 scale (Most Infrequently - All of the Time) indicated a generally positive perception of these indicators of group dynamics and productivity with all item means between 4 and 5. The scale items reported most frequently and, thus, favorably, include “My viewpoint is heard” (m = 4.7); “I feel there is good communication and respect between community and university collaborators” (m = 4.6); “I have felt comfortable participating in group meetings and discussions” (m = 4.6); and “I am viewed as a valued member of the group” (m = 4.6). Though still in a favorable range (means between 4.0 - 4.4), less positive responses centered around two general topic areas: 1) Tangible indicators of meeting effectiveness (three items pertaining to Progress, Frequency, and Productivity (combined mean = 4.23); and 2) Community-focused indicators (two items pertaining to Community Participation, and Community Impact (combined mean = 4.04). For the full list of IP items along with descriptive statistics, see Table 2).

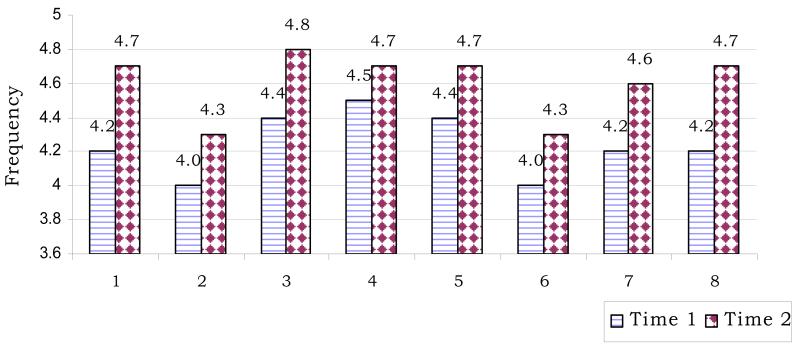

The responses on the IP survey indicated generally more positive perceptions about collaborative processes during the second period of the study as compared to the first. Small increases were evident for 5 items; and were largest for the 8 items displayed in Figure 1. The 4 scale items with the largest average differences, and thus improvements, between period one and two were as follows: Feeling Comfortable in the Group, Feeling Trusting of both Community and Research Collaborators, I feel like my opinions have an effect on group decision-making, and I feel there is good communication and respect between community and university collaborators. One scale item mean was the same across time-points: I am satisfied with the degree of community participation in the project (m = 4.0; sd’s for Time 1 and Time 2 = .71 and .68, respectively), therefore suggesting that while being relatively high at both points, there was no perceived change in terms of community involvement in the project.

Figure 1. Individual Perceptions Scale: Means for Scale Items with the Largest Differences between Time-points.

Scale Constructs included in Figure 1:

#1: I feel comfortable in the group

#2: I am satisfied with the group’s progress

#3: I feel there is good communication and respect between community and university collaborators

#4: I have felt comfortable participating in group meetings and discussions

#5: I am viewed as a valued member of the group

#6: I am satisfied with the frequency of group meetings

#7: I feel like my opinions have an effect on group decision-making

#8: I feel trusting of both community and research collaborators

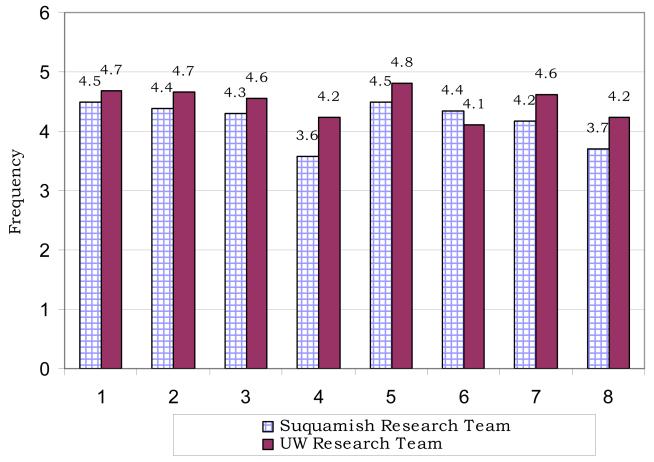

In terms of research team differences, the ART generally tended to perceive the collaboration more favorably relative to the SRT. However, most group differences were not dramatic, with the largest differences between teams occurring for the following three items: 1) I am satisfied with the Degree of Community Participation; 2) I am Satisfied with the Degree of Community Impact on the Project; and 3) I Feel Trusting of both Community and Research Collaborators; notably, the UW responded more favorably across all three items. The largest difference where the SRT scored higher was for Frequency of Group Meetings, thus indicating relatively greater approval by the SRT with respect to how often HOC research meetings were conducted. The 8 items with the largest research team differences on the IP measure are displayed in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Individual Perceptions Scale: Means Across Research Teams.

Scale Constructs included in Figure 2:

1: I feel there is good communication and respect between community and university collaborators

2: I am viewed as a valued member of the group

3: I feel like my opinions have an effect on group decision-making

4: I am satisfied with the degree of community participation in the project

5: My viewpoint is heard

6: I am satisfied with the frequency of group meetings

7: I feel trusting of both community and research collaborators

8: I am satisfied about the degree of community impact on project processes

Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory

The Wilder responses ranged from 3.51 to 4.76 (on an agreement scale from 1 through 5), with an overall mean of 4.26. These responses indicate that research team members generally are between Agreement and Strong Agreement as far as most of these positive indicators of collaborative effectiveness. The weakest reported areas regarding the collaboration include: “Appropriate Cross Section of Members;” “Multiple Layers of Participation”; and “Appropriate pace of development” (means range from 3.51 to 3.83); whereas, those with the highest means include: “Flexibility,” “Favorable Political and Social Climate,” and “Skilled Leadership” (means range from 4.62 to 4.76; See Table 3).

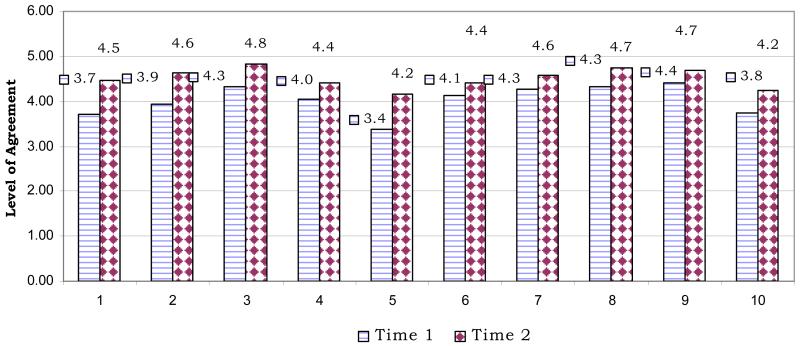

Comparing time periods, there was an increase in desirable perceptions regarding the collaboration between Year One and Year Two for all but one question (Members see collaboration as in their self-interest), but only a small decrease from 4.67 to 4.50 is noted for this item. Many mean differences, while positive, are small (less than .5) and, those with the largest increases in the latter part of the study include Mutual Respect, Understanding, and Trust (Time 1 = 3.7; Time 2 = 4.5); Appropriate Pace of Development (Time 1 = 3.4; Time 2 = 4.2); Members share a stake in both process and outcome (Time 1 = 3.9; Time 2 = 4.6), Flexibility (Time 1 = 4.3; Time 2 = 4.8); and Sufficient funds, staff, materials, and time (Time 1 = 3.8; Time 2 = 4.2). The ten factors with the largest differences between time-points are displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory: Comparison of Means between Time Periods.

Scale Constructs included in Figure 3:

1= Mutual respect, understanding, and trust 6= Open and frequent communication

2= Members share a stake in both process and outcome 7= Concrete, attainable goals and objectives

3= Flexibility 8 = Shared vision

4= Adaptability 9 = Unique purpose

5= Appropriate pace of development 10 = Sufficient funds, staff, materials, and time

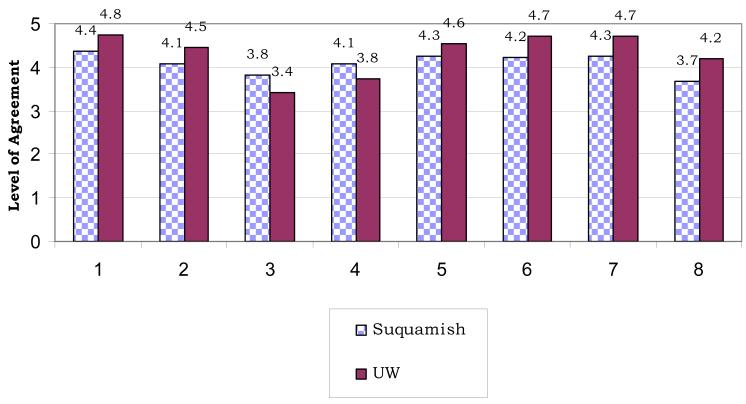

Analyses of differences between research teams on the WCFI indicate that, on average, the ADAI Team again tended to respond more favorably, with the latter group responding with higher averages for 15 out of 19 (79%) collaborative factors. The largest mean differences between teams occurred for the following factors: Sufficient Funds, Staff, Materials, and Time (SRT = 3.67; ART = 4.20); Shared Vision (SRT = 4.22; ART = 4.72); Unique Purpose (SRT = 4.25; ART = 4.70); Multiple Layers of Participation (SRT = 3.81; ART = 3.43); and Appropriate Pace of Development (SRT = 4.07; ART = 3.75). As indicated here, for the last two scale factors the Suquamish Team provided higher average responses relative to the ADAI Team. The SRT also reported higher averages for Members see collaboration as in their self-interest (SRT = 4.62; ART = 4.55), and Development of clear roles and policy guidelines (SRT = 4.00; ART = 3.97), though these differences were small. The 8 factors with the largest differences between means across research teams are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory: Means Across Research Teams.

Scale Constructs included in Figure 4:

1 = Favorable political and social climate

2 = Members share a stake in both process and outcome

3 = Multiple layers of participation

4 = Appropriate pace of development

5 = Concrete, attainable goals and objectives

6 = Shared vision

7 = Unique purpose

8 = Sufficient funds, staff, materials and time

Meeting Effectiveness Inventory

Overall, descriptive analyses suggest that the HOC team regard research meetings in a generally positive light, as all items using the 1 through 5 (Poor through Excellent) scale had means greater than 4.0 (Good). On average, Leadership was reported as between Good and Excellent (mean = 4.3), with the Balance of Leadership between the Chairperson and Staff Members about midway (mean = 3.6) between 50/50 and 25/75 (chair/staff ratio). As noted earlier, chairmanship of meetings was rotated between partners. The highest average rating was evident for Meeting Cohesiveness (4.7), indicating that team members work well together and have achieved a sense of trust among one another. The other areas with the highest ratings include Clarity of Goals for Meeting (mean = 4.5) and General Level of Participation in the Meeting (mean = 4.5) – both halfway between Good and Excellent (see Table 4). As a reminder, MEI analyses cannot be conducted across research teams because this descriptor was not recorded on this instrument. There were no notable differences between time periods for the MEI.

Qualitative Findings

Individual Perceptions of the Collaborative Process

As previously noted, the IP survey contains 3 open-ended questions assessing group processes. Responses to first of these questions (What do you think is the greatest Impact that this collaborative effort has had on the community to date?) were categorized into the following constructs: Tribal Empowerment/Ownership (13 responses); Community Involvement (10 responses); Community Support (7 responses); Youth Impact (6 responses); Trust/Relationship Building (6 responses); and Research-Related Impact (5 responses).

Clearly, the area in which team members feel the project has had the greatest impact is the Promotion of Tribal Empowerment and/or Ownership. The following quotations represent examples of such responses: 1) “Empowering [the community] and gaining interest and trust in the project” (ART); 2) “It has helped to empower community members to take on some of the challenges they have identified” (ART); 3) “Feeling ownership in the project by the Tribe as a whole” (SRT); and 4) “The satisfaction of knowing that [the community] had the opportunity to design and participate in the project” (SRT).

Another key area of focus concerned Getting the Community More Involved both in the Project and With Each Other. Responses indicating a focus on this construct include the following: 1) “Increasing [community] involvement in identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the community, and methods for increasing well-being. Basically involving, respecting and empowering the community” (ART); 2) “Facilitation of community involvement in the project and more interaction with each other” (ART); 3) “Bringing the community together to discuss priority issues to address” (SRT); and 4) “The Suquamish community has been supportive of the project and have taken a real interest in it. Many have participated in the curriculum review meetings and retreat” (SRT). The latter of these quotes also emphasizes the importance of Community Support for the project, as do the following: 1) “The project evaluation indicates that it is viewed positively and particularly likes the blending of culture and substance abuse. They see positive changes in the youth” (ART); and 2) “We have had great meetings with the community about the project. A lot of people are interested and that’s great” (SRT). This data also indicated a specific focus on how the youth are impacted by the project, as exemplified by the following comments: 1) “Chance to demonstrate commitment to youth” (ART); and 2) “The effect we have at community meetings and our effect on the youth” (SRT).

Examples of comments related to Trust-building are as follows: 1) “Building a relationship based on trust and respect with community members, and between the [Suquamish Team] and the [UW Team]” (ART); and 2) “Suquamish communities trust of the University of Washington” (SRT). The final prominent category concerned the project’s impact on research itself, although this was only expressed by members of the UW team. For example, one ADAI team member noted “Increased capacity as consumers of research” as a key impact of the HOC project.

The second open-ended IP question: “In your opinion, what could be done to improve the collaborative group’s effectiveness?” indicated that, by far, both research teams felt that this end could best be met by both research teams Spending More Time Together (20 total responses). For example, team members expressed the need to 1) “Continue to have more time for social interaction and building and maintaining trust” (ART); and 2) “Continue to have [the Suquamish Team] and [the UW Team] meet regularly - face to face time is so important” (SRT). The priority for more time shared between the two research teams included both work-related, more formal types of gatherings, as well as informal social gatherings. Other suggested improvements included More Community outreach (6 responses); Trust building (3 responses); and Focus on the Curriculum (3 responses). Importantly, satisfaction with how things were going was also common. Team members either wrote that “nothing [needs to be done]” (3 responses) or that the project is on the right track and should continue what it’s doing (6 responses).

Similarly, in response to the IP’s final qualitative question: “Is there anything you would do differently if you participated in a collaborative effort in the future?” the most common response was not to do anything differently. On the other hand, suggested improvements were as follows: Authority/Role-Related Improvements, for example 1) “Better clarification of roles;” and 2)“ More clearly specify leadership roles at the outset”, though this was only reported by ADAI team members. Greater care in hiring decisions was another key concern for both teams (4 responses); and, a specific desire for a male to be hired on the Suquamish Team was noted by members from both teams. Several other responses pertained to improvements in the relationship between Suquamish and ADAI research group members, with emphasis on Improved Communication, More Time Together, Relationship Building, and more Cross-Cultural Training. Overall, though, responses to this question suggest general satisfaction in the project, or, as stated by one member of the SRT: “No! This project is going great and I am very satisfied with it”.

Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory

While the WCFI does not contain open-ended questions, the HOC project revised the measure to allow space for comments. Among the 13 comments provided by the research team, the majority (all but two) were made by the ADAI team, thus such comments are biased toward the perceptions of this group. The most recurring theme was Trust. Trust was mentioned in 6 of the comments, for example, “There have been some issues with trust on both sides” (ART); and “Most problems are solved top-down. There have been some personality conflicts that contribute to lack of trust” (SRT). The requirement of Time for the Development of Trust was also noted, for example, “The SRT does not always trust the university team. This is OK, it takes time” (ART); and trust was generally viewed as being more problematic early on in the project and improving over time, for example: 1) “Not sure how trusting the relationship was early on. I think it has gotten better” (ART); 2) “I feel a sense of trust and ease between the UW and Suquamish teams that has steadily increased over time” (ART); and 3) “Trust is still being developed” (ART). The need for increased Community Involvement, particularly Elders and Youth, was noted on 3 occasions by ADAI colleagues. Overall, the ADAI comments were generally optimistic about the future of the project, for example: “It has been such a pleasure to be part of Phase I of this project! Looking forward to all the new developments that will happen in Phase II.”

Meeting Effectiveness Inventory

The MEI was also adapted to provide space for ideas and comments. Among the 13 total comments, there was a focus on Productivity, Use of Time, and Digression from the Agenda. Several team members felt that the meetings veered off-topic, for example: “A little tangential at times” and “Did digress at times!” Example of comments indicating that productivity could have been better include “We could have gotten through agenda more quickly” and “Need to better monitor time”. Therefore, the research team could likely increase perceived effectiveness by more closely monitoring time and content. However, the circumstantial nature of discussion was not always construed as negative, for example: “We digressed but it led to some good problem solving and brainstorming.” This comment suggests that allowing a more social aspect of project meetings also may be important for building rapport, generating new ideas, and simply enjoying each other’s company. Finally, meetings were also considered Productive and Positive, for example: “Well prepared agenda. A lot of input from many perspectives;” and “I thought this was an excellent, productive and fun meeting!2”

DISCUSSION

The research team felt the discussion would be most powerful presented in two distinct but related sections. This first section summarizes and discusses the overall findings. The second section provides reflections on the collaborative process from the perspective of the community partners.

This study provides key insights into the quality of relationships across and between research teams in a university and Tribal partnership grounded in CBPR and TPR. Although preliminary, these process findings illuminate a project with a uniform dedication to its objectives and generally congenial relationships overall between research teams. This view is consistent with the project having been identified as an exemplar of community engagement principles (Duffy, et al., 2011). It demonstrates the evolution over time from different perspectives and two distinct research groups to a common vision, shared goals, and truly collaborative partnership based on the development of trust and community involvement and project ownership.

From the perspective of the tribal partner, for many AIAN tribes, communities and individuals science is just another wave of groups wanting to “help” the Indians similar to the government, the army/military, the churches, etc. Historically this meant that these non-Native entities imposed their own values of what type of “help” is needed rather than what the tribe/community wanted or may have needed. Unfortunately, this scenario has played out with regard to research. Many AIAN communities have experienced researchers “swooping” in with studies that are often irrelevant, at best, and harmful, at worst. AIAN communities consider this “helicopter research”; the data is extracted from a community and the researcher and findings are never seen again. In the course of the current project, Elders in the Suquamish community remembered earlier experiences of being interviewed years ago by “someone from some university somewhere” and never saw the interviewers or data again. Fortunately, the Healing of the Canoe project team was committed to the importance of cultural humility and research that was guided by the Suquamish Tribe and was respectful, ethical, and effective.

This collaboration has been a learning process for the full research team because we come at our work from different perspectives. The Suquamish Tribe as a government implores us as staff to put the tribal members first; this is in line with what we are taught as tribal members so we have a tendency to drop everything when someone comes to our office or if there is a community event or meeting. This has at times been a point of irritation on “both sides of the water” (for community and academic partners). Fortunately, we are all forthright about this issue so that it can be worked out and priorities can be negotiated and revised. This is a terrific example of how we listen to each to each other and how deeply we respect each other and one reason why this partnership is working. We respect our differences, value and utilize our strengths, and allow for our difficulties, be they personal, physical or professional. We have always been able to deal with issues that emerged because we as individuals and as a team are able to be humble as opposed to arrogant. We have committed ourselves to a true partnership based on trust and respect.

Our partnership allows for a different timeline – it is community-driven rather than grant- or IRB-driven. While those things are important and we certainly have to make room for them, they do not take precedence over community timelines. We needed time to build trust and show what we can offer, and the Tribe needed time to think about what the implications of this relationship/partnership would mean and decide if it is a path they want to take and if it is the right time. Then we were able to begin discussions about what type of research, what we should research, and who should research. After this process, we were able to map out a path to reach the Tribe’s goals as well as the aims of the proposed study. An important part of that map included increasing the capacity for research in the community, including processes like obtaining NIH grants and the need for IRB approvals. This provided opportunities to teach our Community Advisory Board (Suquamish Cultural Co-op) about these processes; now the Cultural Co-op asks “Will this change need Human Subjects approval?” or “What will be needed to secure our next grant?” This indicates that the Tribe sees these as important steps in meeting its goal rather than just having more processes imposed on them.

CBPR and TPR allow our community to be in the driver’s seat of how (and if) research is conducted within our reservation with our people. This provides us the opportunity to decide what we would like to see researched so that we may view it from another perspective (rather than only from the perspective of the academy). We as a Tribe may know that a traditional practice works because of the hundreds of years it has been in practice. By partnering in research, we have the opportunity to conduct a community-based culturally grounded study with the hopes of collecting data that supports our practice as a “Best Practice”, affording it all of the prestige and funding it deserves.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by Grant Number R24MD001764 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, U.S. National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health. We would also like to acknowledge the Suquamish Tribe, its Elders, its members, the Suquamish Cultural Co-op, and the Tribal Council for inviting us into the community and being full partners in the research process.

Footnotes

The Suquamish Tribe has approved being named in this paper.

MEI data did not indicate research group.

REFERENCES

- Arviso V, Welle D, Todacheene G, Chee JS, Hale-Showalter G, Waterhouse S, et al. Tools for Iina (Life): The journey of the Iina Curriculum to the Glittering World. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2012;19(1):124–139. doi: 10.5820/aian.1901.2012.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky AE, Senuta KR, Weiss CLA, Marx CM, Loomis C, Arteaga SS, et al. When one plus one equals three: The role of relationships and context in community research. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33(3/4):229–241. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027008.73678.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burhansstipanov L, Christopher S, Schumacher SA. Lessons learned from community-based participatory research in Indian country. Cancer Control. 2005;12(Suppl 2):70–76. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004s10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JY, Davis JD, DuBois B, Echo-Hawk H, Erickson JS, Goins RT, et al. Culturally competent research with American Indians and Alaska Natives: Findings and recommendations of the first symposium of the work group on American Indian research and program evaluation methodology. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2005;12(1):1–21. doi: 10.5820/aian.1201.2005.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher S. Recommendations for conducting successful research with Native Americans. Journal of Cancer Education. 2005;20(1 Suppl):47–51. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001s_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher S, Saha R, Lachapelle P, Jennings D, Colclough Y, Cooper C, et al. Applying Indigenous community-based participatory research principles to partnership development in health disparities research. Family & Community Health. 2011;34(3):246–255. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318219606f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AK, Young S. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(8):1398–1406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SM, Reid R. Practicing participatory research in American Indian communities. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999;69(4 Suppl):755S–759S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.755S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy R, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, McCloskey DJ, Ziegahn L, Silberberg M. Successful examples in the field. In: Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, editor. Principles of Community Engagment. 2nd edition National Institutes on Health; Bethesda, MD: 2011. pp. 57–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Ball TJ. The Indian Family Wellness project: an application of the tribal participatory research model. Prevention Science. 2002;3(3):235–240. doi: 10.1023/a:1019950818048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulks EF. Misalliances in the Barrow Alcohol Study. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1989;2(3):7–17. doi: 10.5820/aian.0203.1989.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP. Research reservations: Response and responsibility in an American Indian community. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, Calf Looking PE. American Indian culture as substance abuse treatment: Pursuing evidence for local intervention. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):291–296. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.628915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, Trimble JE. American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse persepctives on enduring disparities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:11.11–11. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RM, Wandersman A, Chinman M, Imm P, Morrissey E. An ecological assessment of community-based interventions for prevention and health promotion: Approaches to measuring community coalitions. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24(1):33–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02511882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding A, Harper B, Stone D, O’Neill CO, Berger P, Harris S. Conducting research with Tribal communities: Sovereignty, ethics, and data-sharing issues. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012;120(1):6–10. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge F. No meaningful apology for American Indian Unethical Research. Journal of Ethics and Behavior. 2012;22(6):431–444. [Google Scholar]

- Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones A, Mango J, Jones F, Lizaola E. On measuring community participation in research. Health Education & Behavior. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1090198112459050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMarr J, Marlatt GA. Canoe Journey Life’s Journey: A Life Skills Manual for Native Adolescents. Hazelden Publishing and Educational Services; Center City, MN: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lane DC, Simmons J. American Indian youth substance abuse: community-driven interventions. Mt. Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2011;78(3):362–372. doi: 10.1002/msj.20262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeaux D, Christopher S. Contextualizing CBPR: Key principles of CBPR meet the Indigenous research context. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health. 2009;7(1):1–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattessich PW, Murray-Close M, Monsey BR. Collaboration: What makes it work. Amherst H. Wilder Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt GV, Hazel KL, Allen J, Stachelrodt M, Hensel C, Fath R. Unheard Alaska: culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33(3-4):263–273. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027011.12346.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt GV, Rasmus SM, Thomas L, Allen J, Hazel K, Hensel C. “Tied together like a woven hat:” Protective pathways to Alaska native sobriety. Harm Reduction Journal. 2004;1(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neel D. The Great Canoes: Reviving a Northwest Coast Tradition. Douglas & McIntyre Ltd.; Vancouver, BC.: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Rivera A, Morse G, Hunt A. Building a community-based research partnership: Lessons from the Mohawk nation of Akwesasne. Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26(2):163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Powell E, Rossing B, Geran J. Evaluating collaboratives: Reaching the potential. 1998 Available from http://www.uwex.edu/ces/pdande/evaluation/index.html.

- Thomas LR, Donovan DM, Sigo RLW. Identifying community needs and resources in a Native community: A research partnership in the Pacific Northwest. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2010;(8):362–373. doi: 10.1007/s11469-009-9233-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LR, Donovan DM, Sigo RLW, Austin L, Marlatt GA, The Suquamish T. The community pulling together: A Tribal community-university partnership project to reduce substance abuse and promote good health in a reservation Tribal community. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2009;8(3):283. doi: 10.1080/15332640903110476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LR, Donovan DM, Sigo RLW, Price L. Community based participatory research in Indian Country: Definitions, theory, rationale, examples, and principles. In: Sarche MC, Spicer P, Farrell P, Fitzgerald HE, editors. American Indian children and mental health: Development, context, prevention, and treatment. ABC-CLIO, LLC; Santa Barbara, CA: 2011. pp. 165–187. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LR, Rosa C, Forcehimes A, Donovan DM. Research partnerships between academic institutions and American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes and Organizations: Effective strategies and lessons learned in a multisite CTN study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37(5):333–338. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.596976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler L. Behavioral health services “Don’t Work for Us”: Cultural incongruities in human service systems for Alaska Native communities. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47:157–169. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB. Some guiding assumptions and a theoretical model for developing culturally specific preventions with Native American people. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34(2):183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Zakocs RC, Edwards EM. What explains community coalition effectiveness?: A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30(4):351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziff MA, Willard N, Harper GW, Bangi AK, Johnson J, Ellen JE, et al. Connect to Protect® researcher-community partnerships: Assessing change in successful collaboration factors over time. Global Journal of Community Pscychology Practice. 2010;1(1):32–39. doi: 10.7728/0101201004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]