Preface

Purinergic signalling regulates a wide range of cellular processes. Stimulation of virtually any mammalian cell type leads to the release of cellular ATP and autocrine feedback through a diverse set of different purinergic receptors. Depending on the types of purinergic receptors that are involved, autocrine signalling can promote or inhibit cell activation and fine-tune functional responses. Recent work has shown that autocrine signalling is an important checkpoint in immune cell activation that allows cells to adjust their functional responses based on extracellular cues provided by their environment.

Introduction

Cellular ATP serves as an energy carrier that drives virtually all cell functions. Therefore the discovery that intact cells can release a portion of their cellular ATP came as a surprise to most researchers 1. Over the last two decades, a total of nineteen different purinergic receptor subtypes that can recognize extracellular ATP and adenosine have been cloned and characterized 2. These receptors include eight P2Y receptor subtypes, seven P2X receptor subtypes, and four P1 (adenosine) receptor subtypes. In addition, several families of ectonucleotidases that hydrolyze ATP to ADP, AMP, and adenosine have been found 3. Distinct sets of these purinergic receptors and ectonucleotidases are expressed on the cell surface of different mammalian cell types where they regulate cell activation through cell-type specific purinergic signalling systems 4, 5.

Controlled ATP release from intact cells was first discovered in neurons that release ATP into neuronal synapses. Since then many aspects of purinergic signalling in neuron have been elucidated 6. Additional work revealed that similar purinergic signalling processes regulate key aspects of many other physiological processes, including activation of the different cell types of the immune system 7. For example, T cell activation induces the release of ATP through pannexin 1 channels that translocate with P2X receptors to the immune synapse where they promote calcium influx and cell activation through autocrine purinergic signalling 8-11. Neutrophils release ATP in response to chemotactic mediators and autocrine signalling via purinergic receptors regulates chemotaxis 12. Activation of purinergic receptors in immune cells can elicit either positive or negative feedback responses and thus tightly regulate immune responses.

In addition to the autocrine feedback mechanisms that regulate the function of healthy immune cells, purinergic receptors allow immune cells to recognize ATP released from damaged or stressed host cells. Thus, purinergic signalling systems of immune cells serve an important function in the recognition of danger signals and phagocytes recognize ATP that is released by stressed cells as a ‘find-me signal’ that guides phagocytes to inflammatory sites and promotes clearance of damaged and apoptotic cells 13. Purinergic signalling is also critical for the activation of inflammasomes and the release of cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in response to damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) 14.

Several excellent review articles have been published that describe in detail the mechanisms by which mammalian cells release ATP 15, the pharmacological and structural properties of the different purinergic receptors 16-17 and ectonucleotidases 18, and the multiple roles for paracrine purinergic signalling in regulating a wide range of physiological processes including immune cell functions 5,7. This review will therefore focus mostly on autocrine purinergic signalling systems in immune cell activation (Fig. 1) and how these purinergic systems integrate extracellular cues such as danger signals emitted from inflamed tissues.

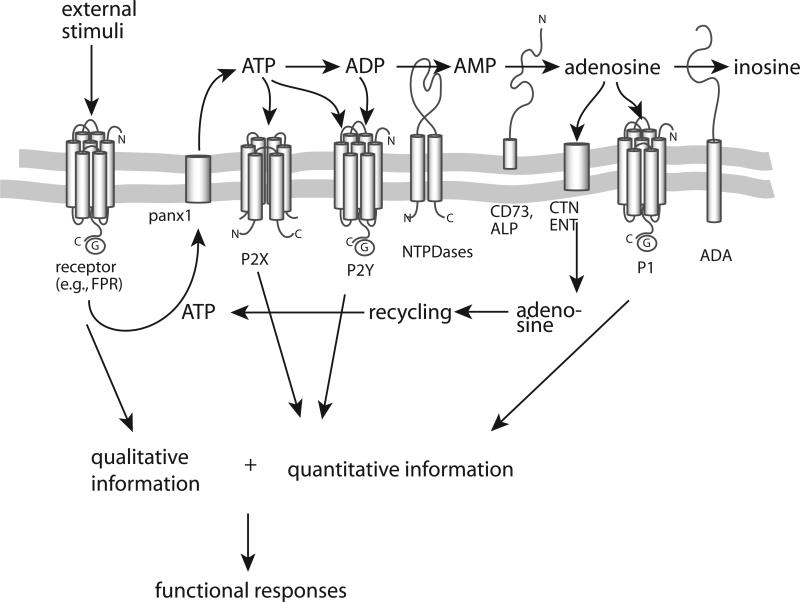

Figure 1. Components of autocrine purinergic signalling systems.

The key elements of purinergic signalling include 1) ATP release from cells in response to activation of a cell surface receptor, for example by the opening of pannexin 1 (panx1) hemichannels in response to stimulation of formyl peptide receptor (FPR); 2) autocrine activation of P2 receptors; 3) hydrolysis of ATP and formation of adenosine by ectonucleotidases; 4) activation of P1 receptors; and 5) removal and recycling of adenosine (shown in blue). Autocrine purinergic signalling provides cells with quantitative cues (shown in red) that define how and to what extent to respond to specific qualitative cues they perceive via surface receptors that detect pathogens, antigens, danger signals, chemokines, and cytokines (shown in green). Autocrine purinergic signalling allows localized stimulation because purinergic signalling can be confined to specific regions and different spatiotemporal combinations of signalling components can be arranged to suite specific functional requirements. Moreover, these autocrine feedback processes can be influenced in paracrine fashion by purinergic receptor ligands that are generated by other cells or infected or damaged tissues.

Components of purinergic signalling

ATP release

Immune cells recognize ATP that is released from damaged tissues and dying cells as danger signal that elicits a variety of inflammatory responses 19-21. In addition to damaged cells, intact cells including immune cells themselves can also release ATP under normal physiological conditions. ATP release from intact cells was first observed in neuronal cells that use vesicular transport to release ATP into the cleft of chemical synapses 22. Nonneuronal cell types can also release ATP through vesicular transport 5; however a number of additional mechanisms have been reported. These mechanisms include release through stretch-activated anion channels, voltage-dependent anion channels, P2X7 receptors (a purinergic receptor subtype involved in opening large pores in the cell surface), and connexin and pannexin hemichannels 15. Pannexin 1 hemichannels were recently found to promote ATP release from several different immune cell types. Like connexin hemichannels, pannexin hemichannels are thought to from gap junctions between adjacent cells, allowing rapid intercellular communication such as those of electrical synapses in neurons. In individual cells like immune cells, these hemichannels can release ATP. Pannexins are comprised of three members (pannexin 1-3) and are distant relatives of the larger connexin family with twenty-one members 23-25. In mouse neutrophils ATP appears to occur through connexin 43 hemichannels 26. Human neutrophils release ATP through pannexin 1 in response to stimulation of formyl-peptide receptors, Fcγ receptors, IL-8 receptors, C5a receptors and leukotriene B4 receptors 27. Pannexin 1 also facilitates ATP release from T cells after engagement of the T cell receptor (TCR) and CD28 co-receptor or exposure of T cells to osmotic stress 9, 11. The surface expression of pannexin 1 is highly dynamic and the stimulation of T cells and neutrophils causes translocation and accumulation of pannexin 1 at the immune synapse and leading edge of polarized neutrophils, respectively 11, 27.

Extracellular ATP metabolism

Upon its release into the extracellular space, ectonucleotidases rapidly hydrolyze ATP to ADP, AMP and adenosine in a step-by-step manner 18. This process terminates P2 receptor activation, prevents receptor desensitization and sets the stage for rapid and repeated signalling via purinergic inside-out signalling. Four families of ectonucleotidases that hydrolyze extracellular ATP have been identified in mammalian cells. These ectoenzymes include the ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (ENTPD) family, the ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (ENPP) family, alkaline phosphatase and ecto-5’-nucleotidase (also known as CD73) 3, 18, 28. The ENTPD family comprises seven different isoforms (ENTPD1-6 and ENTPD8) of which ENTPD1-3 and ENTPD8 are known to hydrolyze ATP or ADP to AMP with different substrate preferences. The three members of the ENPP family (ENPP1-3) hydrolyze ATP to AMP and pyrophosphate. Finally, the four members of the alkaline phosphatase family (intestinal, placental, germ cell and tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase) can hydrolyze ATP, ADP, and AMP to adenosine, while a single ecto-5’-nucleotidase isoform (CD73) converts AMP to adenosine 3, 18. Ectonucleotidases are found on the surfaces of virtually all mammalian cell types with distinct distribution patterns that define cell-specific local purinergic ligand environments.

Adenosine turnover and cellular reuptake

Extracellular adenosine, the ligand of P1 receptors, can be ‘neutralized’ by adenosine deaminase (ADA) that converts adenosine to inosine or by cellular reuptake via concentrative nucleoside transporters (CNTs) or equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENTs) 29, 30. In addition to these mechanisms, adenosine kinase can convert extracellular adenosine back to AMP 18. Two different members of ADA, ADA1 and ADA2, are found on the surface of many different cell types, including leukocytes 31-35. Both isoforms promote costimulatory signalling at the immune synapse, which results in increased production of T helper 1 (TH1)-type cytokines and increased T cell proliferation 36, 37. The importance of ADA is further underscored by the fact that a genetic disorder resulting in ADA deficiency causes severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), a condition characterized by impaired T and B cell development and an increased risk of infection due to excessive A2a adenosine receptor activation 36, 38, 39.

Adenosine reuptake is accomplished by two structurally unrelated families of nucleoside transporters, four equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT1–4) isoforms and the three concentrative nucleoside transporters (CNT1–3) 29, 30, 39. The best characterized ENT family members, ENT1 and ENT2, are inhibited by widely used drugs such as dipyridamole, dilazep and draflazine 40. ENTs are involved in the activation of T cells 41, B cells 42 and macrophages 43. While relationships between nucleoside transporters and lymphocyte proliferation have been established 44, little is known about the underlying mechanisms. The ubiquitous expression of nucleoside transporters in different tissues suggests however that they may recharge purinergic signalling systems by recycling adenosine.

Purinergic receptors

The most widely studied elements of purinergic signalling systems are the purinergic receptors that respond to extracellular ATP, adenosine, and related nucleotides. Purinergic receptors are divided into three major families based on their pharmacological and structural properties (Table 1) 2. P2X receptors function as ATP-gated ion channels that facilitate influx of extracellular cations, including calcium. Although all P2X receptors respond only to ATP, they do so with different ligand affinities and kinetics of ligand-induced receptor desensitization 45. Among P2X receptors, the P2X7 subtype has a special place, as micromolar ATP concentrations elicit its ion channel function, while higher ATP concentrations, in the millimolar range, induce P2X7 to form large conductance pores that are involved in apoptosis 45. P2Y receptors are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that recognize ATP and a number of other nucleotides, including ADP, UTP, UDP and UDP-glucose. These receptors can bind to a number of different G proteins (Table 1). P1 receptors are also GPCRs and recognize adenosine. A2a and A2b receptors couple to stimulatory G proteins (Gs) and typically suppress cell responses by upregulating intracellular cAMP levels. By contrast, A1 and A3 receptors couple to Gi/o or Gq/11 proteins and promote cell activation.

Table 1.

Purinergic receptors and downstream signalling

| Receptor | Ligands5,7 | Ligand binding affinities EC50 (μM)7 | Desensitization, G protein coupling16,45 | Main downstream signaling events16 | Expression in different immune cell types7 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMN | Mo | MΦ | DC | B cells | B cells | NK cells | |||||

| P2X ATP receptors | |||||||||||

| P2X1 | ATP | 0.05-1 | <1 s | Ca2+ and Na+ influx | + | + | + | + | + | +92 | + |

| P2X2 | ATP | 1-30 | >20 s | Ca2+ influx | nd11 | nd | nd | nd | nd | +92 | nd |

| P2X3 | ATP | 0.3-1 | <1 s | cation influx | nd11 | nd | nd | nd | nd | +92 | +93 |

| P2X4 | ATP | 1-10 | >20 s | Ca2+ influx | + | + | + | + | + | +92 | + |

| P2X5 | ATP | 1-10 | >20 s | ion influx | + | + | + | + | + | +92 | nd |

| P2X6 | ATP | 1-12 | - | ion influx | nd11 | nd | nd | nd | nd | +92 | +93 |

| P2X7 | ATP | >100 | >20 s | cation influx and pore formation | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| P2Y nucleotide receptors | |||||||||||

| P2Y | G-protein | ||||||||||

| P2Y1 | ADP | 8 | Gq/11 | PLCβ | + | + | + | + | + | +92 | +93 |

| P2Y2 | ATP, UTP | 0.1, 0.2 | Gq/11, Gi/o | PLCβ, cAMP inhibition | + | + | + | + | + | +92 | +93 |

| P2Y4 | UTP (ATP, UDP) | 2.5 | Gq/11, Gi/o | PLCβ, cAMP inhibition | nd11 | + | + | + | + | +92 | nd |

| P2Y6 | UDP, UTP | 0.3, 6 | Gq/11 | PLCβ | + | + | + | + | + | +92 | nd |

| P2Y11 | ATP | 17 | Gs, Gq/11 | cAMP, PLCβ | nd11 | + | + | + | + | + | nd |

| P2Y12 | ADP | 0.07 | Gi/o | cAMP inhibition | +11 | + | + | + | +92 | nd | |

| P2Y13 | ADP, ATP | 0.06, 0.26 | Gi/o | cAMP inhibition | +11 | + | nd | + | + | +92 | nd |

| P2Y14 | UDP-glucose | 0.1-0.5 | Gq/11 | PLCβ | + | nd | nd | + | + | +92 | +93 |

| P1 adenosine receptors | |||||||||||

| A1 | ADO | 0.2-0.5 | Gi/o | cAMP inhibition | + | + | + | + | nd | nd | nd |

| A2a | ADO | 0.6-0.9 | Gs | cAMP | + | + | + | + | + | + | +93 |

| A2b | ADO | 16-64 | Gs | cAMP | + | + | + | + | + | nd | +93 |

| A3 | ADO | 0.2-0.5 | Gi/o, Gq/11 | cAMP inhibition, IP3 | + | + | + | + | + | nd | +93 |

Purinergic receptors are divided into the P1, P2X, and P2Y subfamilies that respond to different nucleotide/nucleoside ligands with a range of binding affinities2, 7, 16, 45. In addition to the P2Y receptors shown in this table, genes of related receptors p2y3, p2y5, p2y7, p2y8, p2y9, p2y10 were cloned but found not to respond to purinergic ligands, except for P2Y3, which is an avian analogue of the mammalian P2Y6 receptor.

Purinergic signalling systems

Different cell types express distinct sets of the purinergic signalling components described above, which allows the formation of customized purinergic signalling complexes (Fig. 1). These complexes permit immune cells to mount unique responses to ATP, adenosine and the other ligands described in Table 1. The role of purinergic signalling as paracrine mechanism of intercellular communication among immune cells has been widely recognized 7. However, recent findings show that purinergic signalling in immune cells has additional roles that are less well known. ATP release from damaged or stressed cells serves as an important danger signal that induces specific immune responses and ATP can be released from immune cells themselves in response to normal cell stimulation. This triggers autocrine purinergic feedback mechanisms that are essential regulators of immune cell responses. Crosstalk of paracrine signals with autocrine purinergic signalling mechanisms makes it possible for immune cells to adapt their responses to extracellular cues generated by surrounding cells in different tissues.

Purinergic activation of immune cell responses

Immune cells have developed highly sensitive receptor systems that allow them to execute their many roles in immune surveillance and host defence. To perform these tasks effectively, neutrophils, for example, must detect trace amounts of chemoattractants that help them locate and migrate to sites of infection and inflammation 46. T cells are able to perform the astonishingly difficult task of recognizing single antigen molecules with great selectivity and sensitivity 47. Although it is clear that these extraordinary feats require sophisticated signal amplification systems, the nature of these amplification mechanisms has remained unclear. Recent findings have shown that stimulation of neutrophils and T cells leads to the rapid release of ATP that triggers autocrine purinergic feedback loops that amplify weak extracellular stimuli the cells receive from their extracellular environment.

Regulation of neutrophil and macrophage chemotaxis

Stimulation of chemotaxis receptors induces rapid ATP release from neutrophils, which is required to recognize chemotactic gradients that guide neutrophils to the source of chemotactic stimuli released by invading microorganisms or inflamed tissues 12. A new method that allows direct imaging of ATP release from live cells has revealed that ATP is released in a polarized fashion, resulting in the accumulation of extracellular ATP near the cell surface closest to the source of chemoattractants. The released ATP can activate multiple adjacent P2Y2 receptors that provide autocrine signal amplification, which greatly increases the intracellular signals generated by chemotactic stimuli (Fig. 2). Inhibiting purinergic signalling by blocking ATP release or P2Y2 receptors or by hastening the removal of extracellular ATP impairs chemotaxis. Similarly, overwhelming the endogenous autocrine purinergic systems by adding excessive exogenous ATP also blocks chemotaxis 12. This shows that altered ATP concentrations in the extracellular environment can modulate chemotaxis by interference with the autocrine signalling systems of neutrophils.

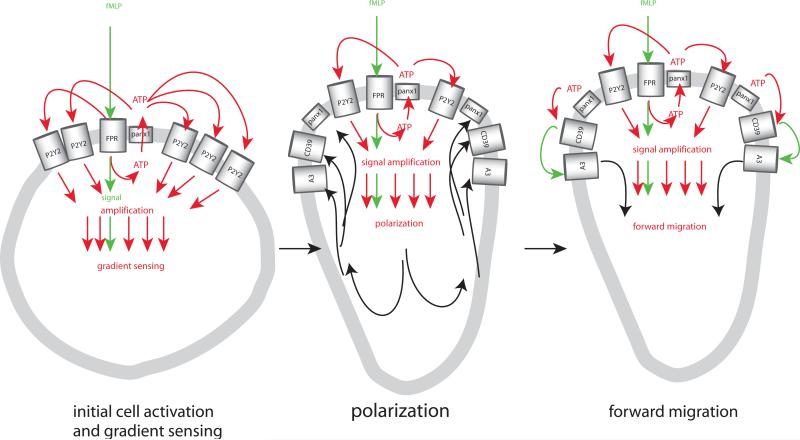

Figure 2. Purinergic signal amplification regulates neutrophil chemotaxis.

Neutrophil activation by bacterial formylated peptides such as fMLP requires stimulation of formyl peptide receptors (FPRs) that induce qualitative signals allowing the cells to recognize chemotactic cues (shown in green) that induce the release of ATP via pannexin 1, resulting in activation of adjacent P2Y2 receptors that provide signal amplification (shown in red) and facilitate gradients sensing (left), allowing cells to polarize within the chemotactic gradient filed (centre), which results in the translocation (shown in back) of pannexin 1, ENTPD1 (CD39), and A3 receptors to the leading edge. Accumulation of these purinergic signalling components facilitates focused ATP release and formation of adenosine at the leading edge, which leads to autocrine activation of A3 receptors that promote cell migration towards the source of fMLP (right). Unpublished work suggests that negative autocrine feedback via A2a adenosine receptors that block cell activation and remain uniformly distributed across the cell surface support chemotaxis by promote retraction of the receding edge (not depicted).

Chemotaxis is a complex process that involves gradient sensing, cell polarization and directed migration. Gradient sensing is the process by which a cell detects chemoattractants and recognizes differences in chemoattractant concentrations in its extracellular environment. During cell polarization, a cell assumes an elongated shape that aligns within the chemotactic gradient field. At the same time, specific receptors and signalling molecules translocate to the leading and receding edges. Finally, directed migration is the actual forward movement of a cell within a chemoattractant gradient field. Recent studies have shown that autocrine purinergic feedback mechanisms control several aspects of these different processes. Initially, stimulation of chemotaxis receptor induces ATP release and activation of multiple adjacent P2Y2 receptors. This process can be thought of as an inside-out signalling event, where ATP serves as a second messenger that amplifies chemotaxis signals through nearby P2Y2 receptors. During cell polarization, purinergic signalling molecules such as pannexin 1, ENTPD1 and A3 adenosine receptors translocate to the leading edge, where membrane ruffling and pseudopod protrusion release additional ATP that is converted to adenosine by ENTPD1 12, 27, 48. Finally, adenosine activates A3 receptors that are concentrated at the leading edge and this additional purinergic feedback loop promotes migration and forward movement of neutrophils towards the source of chemoattractants (Fig. 2) 49. Exogenous ATP and adenosine have long been known to modulate neutrophil responses 50-56. The discovery of the autocrine purinergic signalling systems described above sheds light on the underlying mechanisms by which these compounds regulate chemotaxis. Similar autocrine signalling systems were recently identified in macrophages that regulate chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors as well as P2Y12, A2a, and A2b receptors 57. Interestingly, A2a receptors play also a role in chemotaxis of microglia where these receptors control uropod retraction 58. In addition to the GPCR-type purinergic receptors involved in these mechanisms 12, 57, 59, recent work by Lecut et al. has shown that the structurally different P2X1 receptor can regulate chemotaxis of neutrophils via Rho kinase activation 60.

Regulation of chemotaxis of other cell types

Purinergic signalling may also be involved in chemotaxis of other immune cell types. ATP itself, when released from injured cells, has been reported to induce chemotaxis as well as phagocytosis of microglia through P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptors and P2Y6 receptors, respectively 61-66. Similar observations were reported for mast cells, monocytic cells, dendritic cells, and eosinophils 67-70. A drawback of many of these studies is however that chemotaxis was not observed directly, i.e. under a microscope, but rather indirectly using transwell assay systems which do not differentiate between chemotaxis and chemokinesis. Thus it is possible that ATP increases random migration of some of these cell types rather than promoting chemotaxis. Similarly, purinergic receptor knockout or silencing experiments, although extremely useful, can yield ambiguous results that must be carefully considered because loss of chemotaxis does not necessarily indicate that a specific purinergic receptor is a true chemotaxis receptor. Instead, the receptor may be required for autocrine purinergic signalling systems that regulate chemotaxis to other stimuli, for example DAMPs or PAMPs released at inflammatory sites. ATP and danger signals may also induce sentinel cells to secrete interleukin-8 (IL-8) and other chemokines that recruit cells of interest to inflammatory sites 71-74.

Such interconnected mechanisms including ATP release, inflammasome activation, IL-8 secretion and FPR-mediated chemotaxis were recently shown to regulate recruitment of neutrophils to sites of inflammation 75. The authors concluded that ATP release from inflammatory sites does however not serve as a chemoattractant. This is in contrast to other reports suggesting that apoptotic cells release ATP via pannexin 1 and that ATP itself serves as powerful find-me signals that recruits monocytes 13, 76. It remains to be seen whether this response involves additional chemotactic mediators that are released from apoptotic cells along with ATP. Given the ubiquitous nature of ATP release by healthy cells, chemotaxis towards ATP would seem counterproductive under most physiological circumstances and it seems more likely that released ATP regulates chemotaxis rather than inducing it (Fig. 3).

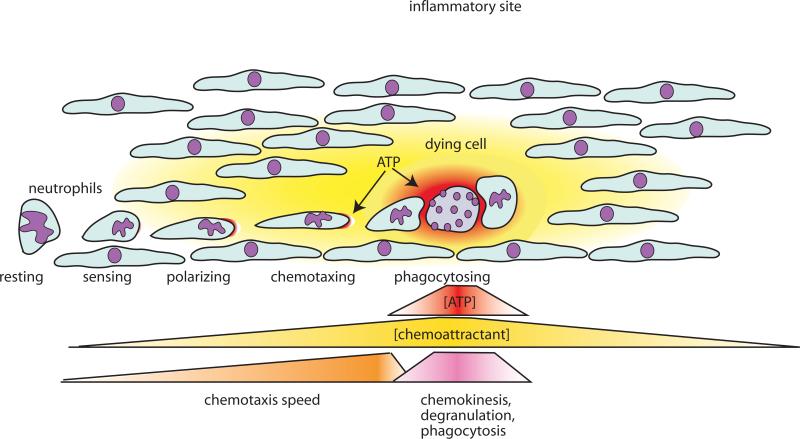

Figure 3. Regulation of phagocyte chemotaxis by autocrine and paracrine purinergic signalling mechanisms.

Phagocytes such as neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages require autocrine purinergic signalling and chemoattractants (danger signals) issuing from inflamed and infected sites to detect and migrate to such danger signals. Long-range signals such as fMLP, IL-8 and other chemoattractants promote the recruitment of phagocytes to affected tissues. ATP that is released from target cells is short lived and can thus only serves as a short-range signal that regulates the final encounter of phagocytes with the target cells. At this stage, ATP released from target cells entraps phagocytes by interfering with the autocrine purinergic signalling mechanisms (see Fig. 3), by promoting random migration, and by upregulating phagocytosis and other phagocyte killing mechanisms that result in effective clearance of target cells.

Signal amplification in T cells

T cells recognize antigen through TCRs that localize to the immune synapse and physically interact with peptides presented on MHC molecules by antigen-presenting cells (APCs). A surprisingly low number of peptide–MHC complexes are required for T cell activation 77 and it is unclear how such weak signals are able to provide sufficiently strong stimulatory signals to activate T cells during their brief encounter with APCs. In order to respond with high sensitivity and selectivity to their antigens, it is clear that T cells must possess mechanisms that permit signal amplification 78. Several models of TCR signalling have been proposed 47, 78. The serial triggering model assumes that a single peptide–MHC complex can activate multiple TCRs in fast succession. Kinetic proof-reading models may explain how T cells can be either activated or remain at a resting state based on the often very small differences in antigen binding affinities of their TCR to different antigens they encounter. Cooperative models propose that multiple TCR complexes cooperate through physical contact or second messengers, allowing T cells to distinguish rare high-affinity antigens from the high background signal generated by the abundance of low affinity binding events. It was proposed that mechanical forces exerted on T cells and accessory cells as a result of TCR engagement are critical for T cell activation and antigen recognition 79. Recent evidence suggests that purinergic signalling at the immune synapse could provide the elusive signal amplification mechanism needed for antigen recognition.

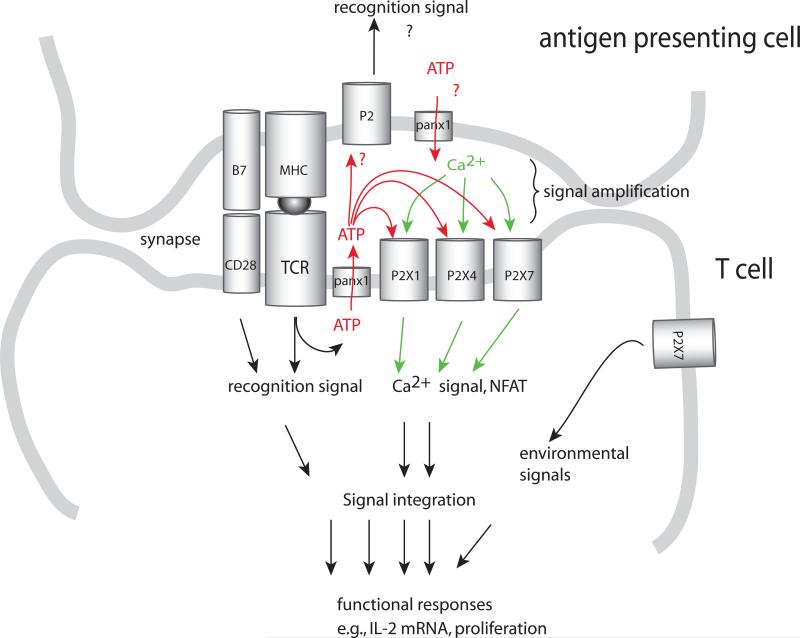

A number of studies have shown that T cells can release ATP in response to various extracellular stimuli, suggesting that purinergic signalling may indeed play an active role in T cell activation 8, 80, 81. T cells express many members of the P2X, P2Y, and P1 receptor families as well as ENTPD182-84. Recent findings by Schenk et al. have revealed that TCR stimulation triggers the release of cellular ATP through pannexin 1 9. Pannexin 1 translocates to the immune synapse where it releases ATP and promotes T cell activation, suggesting that autocrine purinergic feedback processes similar to those identified in neutrophils also regulate T cell activation 9-11. However, while neutrophils seem to amplify stimulatory signals via P2Y2 receptors, purinergic signal amplification in T cells occurs via P2X1, P2X4 and P2X7 receptors. P2X receptors can function as calcium channels and autocrine activation of these receptors facilitates calcium influx and downstream signalling leading to IL-2 transcription 11. Interestingly, two of the three P2X receptor subtypes involved in this autocrine signalling process, P2X1 and P2X4, translocate along with pannexin 1 to the immune synapse within minutes after TCR stimulation 11. This increases the effectiveness of purinergic signalling by concentrating key signalling elements within the immune synapse. Although P2X7 receptors are found at the immune synapse, they do not translocate in response to TRC stimulation and the majority of P2X7 receptors remains uniformly distributed across the cell surface. This suggests that different P2X receptor subtypes have different functions in the different steps involved in T cell activation and that P2X7 receptors may allow T cells to remain responsive to ATP generated by surrounding tissues and cells not directly involved in antigen presentation.

Like with polarized neutrophils, the translocation of pannexin 1 and P2X receptors to the immune synapse allows for strong positive purinergic feedback mechanisms that are further amplified in the confined space of the synaptic cleft (Fig. 4). Under such conditions, it is feasible to propose that ATP release in response to engagement of a single TCR complex could indeed result in the activation of a sufficiently large number of P2X receptors that would elicit powerful and selective T cell responses.

Figure 4. Purinergic signalling in T cell activation.

Antigen recognition requires stimulation of the T cells via the immune synapse that froms between T cells and antigen-presenting cells (APCs). The immune synapse contains a large number of signalling molecules that are required for T cell activation, including TCRs, MHC molecules, costimulatory receptors and the purinergic signalling receptors P2X1, P2X4 and P2X7. In response to TCR and CD28 stimulation, pannexin 1 (panx1), P2X1 receptors, and P2X4 receptors translocate to the immune synapse. ATP released through pannexin 1 promotes autocrine signalling via the P2X receptors. Confinement of ATP in the immune synapse provides a powerful autocrine feedback mechanism that facilitates signal amplification required fro antigen recognition. P2 receptors and ATP release by APCs may play additional important roles in regulating the antigen recognition process.

Purinergic regulation of other immune cells

Although there is no direct proof, ample indirect evidence suggests that autocrine purinergic signalling could regulate the activation of many other immune cell types in addition to those discussed above. Most immune cells express at least some of the different P1 and P2 receptors and are able to release ATP 7, 85-88. B cells, for example, release ATP and extracellular ATP increases B cell proliferation 87, 88. In addition to dendritic cells, monocytes, macrophages and eosinophils, extracellular ATP has been shown to also regulate migration of NK cells 89. Because virtually all mammalian cell types possess purinergic receptors and most, if not all cells, release ATP in response to cell stimulation, there is little doubt that autocrine purinergic signalling regulates functional responses of many of these cell types. Thus autocrine purinergic signalling seems to be are recurring theme in mammalian cell activation. In support of this conclusion, recent work with HEK cells has revealed that stimulation of non-immune cells via different adrenergic receptor subtypes also involves autocrine purinergic signalling via P1 and P2 receptors 90. Future work in this area will undoubtedly provide exiting new insights regarding the multitude of roles of autocrine purinergic signalling in immune cell activation.

ATP as a danger signal

Necrotic and apoptotic cells release ATP, which can serve as a find-me signal that attracts monocytes whose task it is to phagocytose and remove dead or dying cells 13, 20. This process involves the activation of P2Y2 receptors on monocytes that are thought to follow ATP gradients to find their way to apoptotic cells. However, because of the short half-life of ATP in most tissues it is uncertain whether this process alone could attract phagocytes over long distances 20, 82. It is more likely that damaged and stressed cells release additional find-me signals that could be involve in the recruitment of phagocytes 75, 91. Recently, formylated peptides released from the mitochondria of damaged cells have been shown to induce inflammation and neutrophil activation and chemotaxis in response to severe trauma and sterile inflammation 75, 92. Such chemotactic mediators together with chemokines and ATP likely orchestrate the complex processes that guide phagocytes during their long-range approach to and their final encounter with target cells at inflammatory foci 75. This may also be true for pathological situations such as those after severe trauma or cancer therapy, where ATP release and danger signals emitted by damaged cells stimulate host immune responses via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs). Interestingly, recent work has shown that NLRs, which form multi-protein complexes referred to as inflammasomes can be activated by extracellular ATP. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes (also known as NALP3) has been shown to involve ATP release via pannexin 1 and purinergic signalling that involves P2X7 receptors. NLRP3 inflammasome activation triggers innate immune defences by inducing the maturation of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β in a caspase-1 dependent fashion 21, 71, 93. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes has also been observed in response to tumour cell destruction after cancer therapy 20. This process releases DAMPs and ATP that stimulate P2X7 receptors and the NLRP3–ASC–caspase-1 inflammasome of dendritic cells, facilitating IL-1β production and promoting immunity against tumours 94. The exact mechanism how purinergic signalling is linked to NLRP3 inflammasome activation remains to be determined. However, it is intriguing to speculate that autocrine purinergic signalling events could be involved in this and other immune cell responses to DAMPs and PAMPs.

Purinergic inhibition of immune responses

Through the different mechanisms described above, extracellular ATP promotes immune cell activation and pro-inflammatory responses, particularly when ATP is released acutely, for example, in response to cell stimulation, stress and tissue damage, and when extracellular ATP is present at high concentrations. However, ATP can also have anti-inflammatory effects, particularly when extracellular ATP is generated chronically and at low concentrations 19, 95, 96. Such dual effects of released ATP were observed with dendritic cells, monocytes, CD4+ T cells and neutrophils 69, 97-101. Which of these effects are elicited in different cell types depends on the particular P2 receptor subtypes that are stimulated on the cell surface. P2 receptor desensitization and internalization in response to chronic or high extracellular ATP concentrations and the activation of suppressive P1 and P2 receptors (e.g. A2a or P2Y11) are additional mechanisms that may affect the responses of different immune cell types to ATP.

T cell suppression

A2 type adenosine receptors have a major role in suppressing immune responses. The complex network of ectonucleotidases that regulates the ligand availability for P1 and P2 receptors in different tissues have a central role in defining immune responses in these tissues 7, 18. ENTPD1 (CD39), which converts ATP to AMP, the precursor of adenosine and 5’-ectonuleotidase (CD73) that forms adenosine from AMP are particularly important for the balance between the pro- and anti-inflammatory effects of released cellular ATP 28. This can be observed in ENTPD1-deficient mice that develop more severe injury-induced inflammation than wild-type mice, apparently due to the reduced ATP hydrolysis, adenosine formation and A2a receptor activation 102. The other key enzyme involved in adenosine formation, 5’-ectonuleotidase has been shown to play an important role in cancer immunity. Several recent papers have demonstrated that cancer cells express high levels of 5’-ectonuleotidase and that this ectoenzymes is responsible for the production of adenosine in the tumour microenvironment 103, which suppresses tumour immune surveillance by impairing the function of anti-tumour CD8+ T cells via A2a receptors 104. Similar A2a receptor-driven purinergic signalling events attenuate allograft rejection in different animal models by impairing T cell responses 105-106. ENTPD1 and 5’-ectonuleotidase are expressed on the surface of T regulatory cells which allows these cells to convert extracellular ATP to adenosine that suppresses effector cells via A2a receptors 107. ENTPD1 expression of T regulatory cells has been recently shown to play an important role in the impairment of NK activity which leads to metastatic growth in mouse tumour model 108. Thus, the functions of T cells can be suppressed by autocrine or paracrine purinergic signalling loops that involve hydrolysis of extracellular ATP originating from T regulatory cells, effector cells, or from target cells including tumour cells. Although much evidence suggests that A2a receptors have a central role in the downregulation of T cell function by autocrine purinergic signalling, it remains to be seen how P2Y receptors and particularly the Gs coupled P2Y11 receptors contribute to this process.

Inhibition of phagocyte function

Among the Gs coupled P1 receptors, neutrophils express A2a and, to a lesser extent, A2b adenosine receptors. In polarized neutrophils, A2a receptors remain uniformly distributed across the cell surface 12, which suggests that A2a receptors may provide a global inhibitory signal that is an important requirement for efficient chemotaxis 46. Neutrophils convert extracellular ATP rapidly to adenosine 12, 48 which provides a powerful counterpoint to the stimulatory effects P2Y2 and A3 receptors and the suppressive action of A2a receptors seems to provide an important mechanism to limit neutrophil activation and functions including oxidative burst, degranulation and phagocytosis 12, 48, 51, 109. Because of its predominant role in downregulating neutrophils and other immune cells, A2a receptors have been extensively investigated as targets for anti-inflammatory therapeutic approaches to treat patients with asthma, arthritis and other acute and chronic inflammatory diseases 110.

Therapeutic targeting of purinergic signalling

Purinergic receptors are attractive therapeutic targets to treat a range of diseases because they are accessible at the cell surface. However, subtype-specific agonists and antagonists are currently available only for P1 receptors and a few of the fifteen different P2 receptors. Because of this limitation and the incomplete understanding of the varied roles of different P2 receptors in different physiological and pathophysiological processes, only a small number of purinergic drugs are currently in clinical use or being tested in clinical trials. Platelet-targeting drugs such as clopidogrel (Plavix) act as P2Y12 receptor antagonists and are an exception. These drugs prevent platelet aggregation and are used to treat vascular ischemic events in patients with atherosclerosis and acute coronary syndrome and thus these drugs are among the most widely used pharmaceuticals today111. Although the pharmacological actions of these drugs are thought to be platelet specific, it is likely that immune cells that express P2Y12 receptors are also affected (Table 1). One of the most common side effects of clopidogrel is severe neutropenia, which may be an indication for such off-target effects 112.

Compared to the P2 receptors, a much wider selection of powerful and specific drugs is available for the modulation of adenosine receptors 113-115. Many of these drugs are derivatives of caffeine and have been extensively tested and shown to be effective in treating acute and chronic inflammatory diseases in preclinical trials 115. Currently, several drugs are in clinical trials to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases 115. In preclinical trials, several different pharmacological approaches to increase the availability of extracellular adenosine by blocking its re-uptake (for example, with dipyridamole), its conversion to inosine (with ADA inhibitors such as pentostatin and EHNA [Erythro-9-(2-hydroxy-3-nonyl)adenine]), or by increasing the release of adenosine from cells (for example, by low dose treatment with methotrexate, which enhances adenosine release from cells116, 117) have shown strong anti-inflammatory effects under various experimental conditions, including reperfusion injury, sepsis and airway inflammation 115, 116. Several studies have shown that the A3 receptor agonist IB-MECA (1-deoxy-1-[6-[[(3-iodophenyl)methyl]amino]-9H-purin-9-yl]-N-methyl-β-D-ribofuranuronamide) can ameliorate arthritis symptoms in mouse models 118, 119. IB-MECA has also been tested with positive results in a phase II trial in patients with rheumatoid arthritis 120, suggesting that stimulation of A3 receptors attenuates the inflammatory processes involved in rheumatoid arthritis, possibly by A3 receptor desensitization or internalization.

The complexity of the processes by which autocrine and paracrine purinergic signalling mechanisms can control immune cell functions has been a major hurdle in successfully targeting these mechanisms in inflammatory diseases and immune disorders. The rapidly growing knowledge of the purinergic signalling events that regulate immune responses provides new incentives and insights that should foster the development of new drugs and therapeutic approaches to treat major diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ischemia-reperfusion injury, arthritis, sepsis, inflammatory bowel diseases, allergic diseases and asthma.

Conclusions/perspective

ATP release and autocrine purinergic feedback regulate numerous cellular immune responses through inside-out signalling that constitutes a powerful amplification mechanism to increase sensitivity and selectivity of activation responses to cell stimulation. Cells need these autocrine amplification mechanisms to tailor their functional responses to various extracellular cues. Depending on which purinergic receptor subtypes participate in specific purinergic signalling complexes, these autocrine mechanisms can act as checkpoints that enhanced or inhibit activation in response to different extracellular cues. This signalling concept allows for multifaceted intercellular interactions through purinergic interactions among neighbouring cells. This suggests many exciting future directions such as investigating how groups of immune cells use their individual purinergic signalling systems to shape collective responses for example at sites of infection. It will also be very interesting and important to determine how the nature of surrounding tissues affects the autocrine purinergic signalling systems of individual cells, for example neutrophils migrating though these tissues to reach their final target destinations. A number of issues remain to be addressed before we can fully understand and appreciate the diverse roles of autocrine purinergic signalling in immune cell regulation (Box 1).

Box 1. Remaining questions and future directions.

Future research focussing on the specific roles of the different purinergic signalling components in different cell types is likely to yield exciting information. How do these many different family members of P1 and P2 receptors, ectonucleotidases and other components assemble to form autocrine purinergic signalling systems that can shape the many functional responses of different cell types need to execute for successful and appropriate immune responses? Which defects of these complex purinergic signalling systems result in immune disorders and which defects can be compensated for example by substitution of a mutated purinergic receptor with another isoform or splice variant?

Although pannexin 1 appears to be a major player in facilitating ATP release from T cells, neutrophils and monocytes, it is still unclear how other ATP release mechanisms, such as vesicular transport, regulate ATP release and how all possible release mechanisms control cell responses such as antigen recognition, gradient sensing and chemotaxis.

These questions above and a number of other open issues such as the spatiotemporal aspect of ATP release and the dynamics of ATP hydrolysis require new analytical tools to assess ATP release, for example, with novel imaging methods that are more sensitive and technically less challenging than the methods that are currently available 14,121 and with assays that permit the detection of release of ATP and other nucleotides in situ using methods similar to that recently developed by Di Virgilio and coworkers, which allow monitoring of ATP release by whole body luminometric evaluation in mice 122,123.

Another important question that would benefit from such advanced ATP imaging techniques is how purinergic signalling facilitates intercellular communication among immune cells, for example, between dendritic cells and T cells during antigen presentation. Are some purinergic signalling systems at the immune synapse designed to specifically coordinate intercellular communication, while others serve to amplify activation, such as the purinergic systems in chemical and electrical neuronal synapses?

More sophisticated pharmaceutical tools must also be developed to specifically and selectively block different purinergic signalling events. This requires selective inhibitors of release channels such as pannexin 1 and more selective drugs to target the different P2 receptors, ectonucleotidases, adenosine deaminases and nucleoside transporters.

The purinergic signalling field is still in its infancy and much still has to be learned to fully understand the functions of the individual purinergic signalling components. For instance, the role of the many different splice variants of P2X7 receptors is unclear.

Another interesting future direction is to investigate the structure of different autocrine purinergic signalling complexes (Fig. 1). How do these complexes arrange, what controls their translocation and organization during complex cell responses such as chemotaxis and immune synapse formation, and what control mechanisms are in place to rapidly regulate the function of purinergic receptors and their purinergic signalling partners?

Online summary.

Components of purinergic signalling:

The different components that facilitate autocrine purinergic signaling are comprised of various ATP release mechanisms such as pannexin 1, P2X and P2Y receptors that respond to release ATP, ectonucleotidases that hydrolyze ATP to adenosine, P1 receptors that respond to adenosine, and nucleoside transporters and adenosine deaminase that remove adenosine.

Purinergic activation of immune cell responses

Different immune cells express specific combinations of the different purinergic signalling components that play major roles in cell activation by providing activation signal amplification. This positive autocrine feedback loops are essential in phagocyte gradient sensing and T cell antigen recognition.

ATP release can act as a danger signal

When released from damaged, dying and apoptotic cells, ATP can serve as a danger signal that stimulates NLRP3 inflammasomes, promotes chemotaxis of microglia, and boosts activation of other immune cell types that are recruited to sites of inflammation and tissue damage. High ATP concentrations at these sites entrap neutrophils and other phagocytes by interfering with their autocrine purinergic chemotaxis signalling systems.

Purinergic inhibition of immune responses

ATP release and autocrine purinergic signalling can upregulate immune cells by amplifying activation signals but it can also downregulate immune responses either by activating suppressive P2 receptors or via adenosine formation and activation of widely expressed suppressive A2a receptors.

Therapeutic targeting of purinergic signalling

A growing arsenal of pharmacological agents is becoming available to modulate purinergic signalling in immune cells. The most widely investigated drugs are target P1 receptors or the molecular processes that control their ligand, adenosine.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge with great appreciation the work of the many colleagues in this field even though much of their important work could not be cited here. I also thank my co-workers and colleagues. Special gratitude goes to Drs. Yu Chen, Linda Yip, Tobias Woehrle, Yoshiaki Inoue, Yuka Sumi, and Naoyuki Hashiguchi and to my colleagues Drs. Simon Robson and Paul Insel. I also acknowledge the major funding sources that have supported the work in my laboratory: National Institute of Health grants GM-51477, GM-60475, AI-072287, AI-080582, and CDMRP Grant PR043034.

Glossary

- immune synapse

A large junctional structure that is formed at the cell surface between a T cell and an antigen-presenting cell. It is also known as the supramolecular activation cluster. Important molecules that are involved in T cell activation — including the T cell receptor, numerous signal-transduction molecules and molecular adaptors — accumulate in an orderly manner at this site. Immune synapses are now known to also form between other types of immune cell: for example, between dendritic cells and natural killer cells.

- find-me signal

A signal emitted by dying cells to promote the recruitment of scavenger cells that clear the apoptotic cell body.

- inflammasome

A large multiprotein complex formed by a nucleotide-binding domain (NBD)-, leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-containing family (NLR) protein, the adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC) and pro-caspase 1. The assembly of the inflammasome leads to the activation of caspase 1, which cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 to generate the active pro-inflammatory cytokines.

- Pannexin and connexin hemichannels

Pannexin hemichannels and connexin hemichannels of adjoining cells can for gap junction channels between the cells. These channels allow intercellular communication though the exchange of molecules in the cytosol of adjoining cells. In individual cells, pannexin and connexin hemichannels can release cellular ATP into the extracellular space.

- inside-out signalling

The process by which intracellular signalling mechanisms result in the activation of a cell surface receptor, such as integrins. By contrast, outside-in signalling is the process by which ligation of a cell surface receptor activates signalling pathways inside the cell.

Biography

After earning an engineering degree and PhD in Biochemistry at the University of Technology and at the Boltzmann Institute for Traumatology in Vienna, the author performed postgraduate studies in trauma immunology and later joined the faculty at the University of California San Diego. In 2007, he relocated his laboratory to the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School in Boston. The research focus of his laboratory is ATP release and purinergic signalling in inflammation and neutrophil and T cell activation.

Key references

- 1.Burnstock G, Fredholm BB, North RA, Verkhratsky A. The birth and postnatal development of purinergic signalling. Acta Physiol. 2010;199:93–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02114.x. [This is a comprehensive review by the pioneers in the field who describe the development and growth of the purinergic signalling field from its beginning with the initial discovery of ATP to its current widespread scope that encompasses a wide range of research fields.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:413–92. [This review offers an in-depth view of the molecular and pharmacological properties of the known purinergic receptors.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmermann H. Extracellular metabolism of ATP and other nucleotides. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2000;362:299–309. doi: 10.1007/s002100000309. [This review provides detailed information on the various ecto-enzyme families that facilitate the hydrolysis of extracellular ATP and related nucleotides.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnstock G. Unresolved issues and controversies in purinergic signalling. J. Physiol. 2008;586:3307–3312. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.155903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corriden R, Insel PA. Basal release of ATP: an autocrine-paracrine mechanism for cell regulation. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:re1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3104re1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Verkhratsky A, Zimmermann H. Purinergic signalling in the nervous system: an overview. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bours MJ, Swennen EL, Di Virgilio F, Cronstein BN, Dagnelie PC. Adenosine 5'-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006;112:358–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.013. [This comprehensive review article provides a summary of the evidence that purinergic signalling systems are involve in the regulation of virtually all different immune cell subpopulations.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filippini A, Taffs RE, Sitkovsky MV. Extracellular ATP in T lymphocyte activation: possible role in effector functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:8267–8271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8267. [This comprehensive review article provides a summary of the evidence that purinergic signalling systems are involve in the regulation of virtually all different immune cell subpopulations.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schenk U, et al. Purinergic control of T cell activation by ATP released through pannexin-1 hemichannels. Sci. Signal. 2008;1:ra6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1160583. [This paper elucidated the important role of pannexin 1 in facilitating ATP release to drive the autocrine purinergic signalling events that are required for T cell activation.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yip L, et al. Autocrine regulation of T-cell activation by ATP release and P2X7 receptors. FASEB J. 2009;23:1685–1693. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-126458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woehrle T, et al. Pannexin-1 hemichannel-mediated ATP release together with P2X1 and P2X4 receptors regulate T cell activation at the immune synapse. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277707. [Epub ahead of print] [This paper showed that pannexin 1 and two key P2X receptors translocate at the immune synapse where these systems contribute to calcium influx in response to TCR stimulation.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, et al. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [This paper described for the first time that neutrophil chemotaxis is regulated by autocrine purinergic signalling.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott MR, et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [This paper showed that ATP release from apoptotic cells serves as a find-me signal the induces recruitment of monocytes.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trautmann A. Extracellular ATP in the immune system: more than just a “danger signal”. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:e6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.256pe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Praetorius HA, Leipziger J. ATP release from non-excitable cells. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5:433–446. doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9146-2. [This review article provides a thorough overview of the various ATP release mechanisms that are involved in purinergic signalling as well as the methods available to assess ATP release.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbracchio, et al. International Union of Pharmacology LVIII: update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:281–341. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnstock G. Pathophysiology and therapeutic potential of purinergic signaling. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:58–86. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yegutkin GG. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: Important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1783:673–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [This review article provides a thorough overview of the complex enzymatic systems that regulate extracellular concentrations of the ligands of purinergic receptors.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Virgilio F. Purinergic mechanism in the immune system: A signal of danger for dendritic cells. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1:205–209. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-6312-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravichandran KS. Find-me and eat-me signals in apoptotic cell clearance: progress and conundrums. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1807–1817. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling and disorders of the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:575–590. doi: 10.1038/nrd2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahl G, Locovei S. Pannexin: to gap or not to gap, is that a question? IUBMB Life. 2006;58:409–419. doi: 10.1080/15216540600794526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laird DW. Life cycle of connexins in health and disease. Biochem. J. 2006;394:527–543. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacVicar BA, Thompson RJ. Non-junction functions of pannexin-1 channels. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eltzschig HK, et al. ATP release from activated neutrophils occurs via connexin 43 and modulates adenosine-dependent endothelial cell function. Circ. Res. 2006;99:1100–1108. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250174.31269.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, et al. Purinergic signaling: a fundamental mechanism in neutrophil activation. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:ra45. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000549. [This paper shows that autocrine purinergic signalling is an essential event in neutrophil activation.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beldi G, et al. The role of purinergic signaling in the liver and in transplantation: effects of extracellular nucleotides on hepatic graft vascular injury, rejection and metabolism. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:2588–2603. doi: 10.2741/2868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray JH, Owen RP, Giacomini KM. The concentrative nucleoside transporter family, SLC28. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:728–734. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1107-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldwin SA, Beal PR, Yao SY, King AE, Cass CE, Young JD. The equilibrative nucleoside transporter family, SLC29. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:735–743. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franco R, Valenzuela A, Lluis C, Blanco J. Enzymatic and extraenzymatic role of ecto-adenosine deaminase in lymphocytes. Immunol. Rev. 1998;161:27–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cristalli G, et al. Adenosine deaminase: functional implications and different classes of inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev. 2001;21:105–128. doi: 10.1002/1098-1128(200103)21:2<105::aid-med1002>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kameoka J, Tanaka T, Nojima Y, Schlossman SF, Morimoto C. Direct association of adenosine deaminase with a T cell activation antigen, CD26. Science. 1993;261:466–469. doi: 10.1126/science.8101391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciruela F, Saura C, Canela EI, Mallol J, Lluis C, Franco R. Adenosine deaminase affects ligand-induced signalling by interacting with cell surface adenosine receptors. FEBS Lett. 1996;380:219–223. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrera C, Casadó V, Ciruela F, Schofield P, Mallol J, Lluis C, Franco R. Adenosine A2B receptors behave as an alternative anchoring protein for cell surface adenosine deaminase in lymphocytes and cultured cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;59:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franco R, Pacheco R, Gatell JM, Gallart T, Lluis C. Enzymatic and extraenzymatic role of adenosine deaminase 1 in T-cell-dendritic cell contacts and in alterations of the immune function. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2007;27:495–509. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v27.i6.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zavialov AV, Gracia E, Glaichenhaus N, Franco R, Zavialov AV, Lauvau G. Human adenosine deaminase 2 induces differentiation of monocytes into macrophages and stimulates proliferation of T helper cells and macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010;88:279–290. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1109764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Apasov SG, Sitkovsky MV. The extracellular versus intracellular mechanisms of inhibition of TCR-triggered activation in thymocytes by adenosine under conditions of inhibited adenosine deaminase. Int. Immunol. 1999;11:179–189. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Apasov SG, Blackburn MR, Kellems RE, Smith PT, Sitkovsky MV. Adenosine deaminase deficiency increases thymic apoptosis and causes defective T cell receptor signaling. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:131–141. doi: 10.1172/JCI10360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molina-Arcas M, Casado FJ, Pastor-Anglada M. Nucleoside transporter proteins. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2009;7:426–434. doi: 10.2174/157016109789043892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King AE, Ackley MA, Cass CE, Young JD, Baldwin SA. Nucleoside transporters: from scavengers to novel therapeutic targets. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2006;27:416–425. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kichenin K, Pignede G, Fudalej F, Seman M. CD3 activation induces concentrative nucleoside transport in human T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:366–370. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200002)30:2<366::AID-IMMU366>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soler C, Felipe A, Mata JF, Casado FJ, Celada A, Pastor-Anglada M. Regulation of nucleoside transport by lipopolysaccharide, phorbol esters, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human B-lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:26939–26945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soler C, et al. Macrophages require different nucleoside transport systems for proliferation and activation. FASEB J. 2001;15:1979–1988. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0022com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith CL, Pilarski LM, Egerton ML, Wiley JS. Nucleoside transport and proliferative rate in human thymocytes and lymphocytes. Blood. 1989;74:2038–2042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jarvis MF, Khakh BS. ATP-gated P2X cation-channels. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janetopoulos C, Firtel RA. Directional sensing during chemotaxis. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2075–2085. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.035. [This article provides an overview of the current knowledge of the signalling requirements that are needed for efficient chemotaxis.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choudhuri K, van der Merwe PA. Molecular mechanisms involved in T cell receptor triggering. Semin. Immunol. 2007;19:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corriden R, et al. Ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (ENTPDase1/CD39) regulates neutrophil chemotaxis by hydrolyzing released ATP to adenosine. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:28480–28486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800039200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Junger WG. Purinergic regulation of neutrophil chemotaxis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:2528–2540. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8095-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cronstein BN. Adenosine, an endogenous anti-inflammatory agent. J. Appl. Physiol. 1994;76:5–13. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fredholm BB. Purines and neutrophil leukocytes. Gen. Pharmacol. 1997;28:345–350. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ward PA, Cunningham TW, McCulloch KK, Johnson KJ. Regulatory effects of adenosine and adenine nucleotides on oxygen radical responses of neutrophils. Lab. Invest. 1988;58:438–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Palmblad J, Fredholm BB. Biphasic effect of ATP on neutrophil functions mediated by P2U and adenosine A2A receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1996;51:957–965. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de la Harpe J, Nathan CF. Adenosine regulates the respiratory burst of cytokine-triggered human neutrophils adherent to biologic surfaces. J. Immunol. 1989;143:596–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meshki J, Tuluc F, Bredetean O, Ding Z, Kunapuli SP. Molecular mechanism of nucleotide-induced primary granule release in human neutrophils: role for the P2Y2 receptor. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C264–C271. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verghese MW, Kneisler TB, Boucheron JA. P2U agonists induce chemotaxis and actin polymerization in human neutrophils and differentiated HL60 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:15597–15601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kronlage M, et al. Autocrine purinergic receptor signaling is essential for macrophage chemotaxis. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:ra55. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000588. [This report demonstrates that chemotaxis of macrophage is regulated by autocrine purinergic signalling.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Orr AG, Orr AL, Li XJ, Gross RE, Traynelis SF. Adenosine A(2A) receptor mediates microglial process retraction. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:872–878. doi: 10.1038/nn.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kukulski F, et al. Extracellular ATP and P2 receptors are required for IL-8 to induce neutrophil migration. Cytokine. 2009;46:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lecut C, et al. P2X1 ion channels promote neutrophil chemotaxis through Rho kinase activation. J. Immunol. 2009;183:2801–2909. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Honda S, et al. Extracellular ATP or ADP induce chemotaxis of cultured microglia through Gi/o-coupled P2Y receptors. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1975–1982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01975.2001. [This is the first report demonstrating chemotaxis of microglia towards ATP in an ATP concentration gradient field.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Inoue K. Purinergic systems in microglia. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:3074–3080. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8210-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davalos D, et al. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:752–758. doi: 10.1038/nn1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science. 2005;308:1314–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haynes SE, et al. The P2Y(12) receptor regulates microglial activation by extracellular nucleotides. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:1512–1519. doi: 10.1038/nn1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koizumi S, et al. UDP acting at P2Y6 receptors is a mediator of microglial phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;446:1091–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature05704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McCloskey MA, Fan Y, Luther S. Chemotaxis of rat mast cells toward adenine nucleotides. J. Immunol. 1999;163:970–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu QH, et al. Expression and a role of functionally coupled P2Y receptors in human dendritic cells. FEBS Lett. 1999;445:402–408. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schnurr M, et al. ATP gradients inhibit the migratory capacity of specific human dendritic cell types: implications for P2Y11 receptor signaling. Blood. 2003;102:613–620. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Müller T, et al. The purinergic receptor P2Y2 receptor mediates chemotaxis of dendritic cells and eosinophils in allergic lung inflammation. Allergy. 2010;65:1545–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Piccini A, Carta S, Tassi S, Lasiglié D, Fossati G, Rubartelli A. ATP is released by monocytes stimulated with pathogen-sensing receptor ligands and induces IL-1beta and IL-18 secretion in an autocrine way. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:8067–8072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709684105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kukulski F, Ben Yebdri F, Bahrami F, Fausther M, Tremblay A, Sévigny J. Endothelial P2Y2 receptor regulates LPS-induced neutrophil transendothelial migration in vitro. Mol. Immunol. 2010;47:991–999. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ben Yebdri F, Kukulski F, Tremblay A, Sévigny J. Concomitant activation of P2Y(2) and P2Y(6) receptors on monocytes is required for TLR1/2-induced neutrophil migration by regulating IL-8 secretion. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:2885–2894. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hyman MC, et al. Self-regulation of inflammatory cell trafficking in mice by the leukocyte surface apyrase CD39. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:1136–1149. doi: 10.1172/JCI36433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McDonald B, et al. Intravascular danger signals guide neutrophils to sites of sterile inflammation. Science. 2010;330:362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1195491. [This article demonstrates that chemotaxis of neutrophils to inflammatory sites involves a complex network of short-distance and long-distance signals but that ATP release from inflammatory sites is not directly involved in neutrophil recruitment.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chekeni FB, et al. Pannexin 1 channels mediate ‘find-me’ signal release and membrane permeability during apoptosis. Nature. 2010;467:863–867. doi: 10.1038/nature09413. [This paper describes the mechanisms by which apoptotic cells release cellular ATP that serves as a danger signal.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Valitutti S, Müller S, Cella M, Padovan E, Lanzavecchia A. Serial triggering of many T-cell receptors by a few peptide-MHC complexes. Nature. 1995;375:148–151. doi: 10.1038/375148a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van der Merwe PA. The TCR triggering puzzle. Immunity. 2001;14:665–668. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ma Z, Finkel TH. T cell receptor triggering by force. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.09.008. [This review article presents evidence that mechanical forces, which are know to induce ATP release from many cell types, have an important role in signal amplification at the immune synapse.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Canaday DH, Beigi R, Silver RF, Harding CV, Boom WH, Dubyak GR. ATP and control of intracellular growth of mycobacteria by T cells. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:6456–6459. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6456-6459.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Into T, Okada K, Inoue N, Yasuda M, Shibata K. Extracellular ATP regulates cell death of lymphocytes and monocytes induced by membrane-bound lipoproteins of Mycoplasma fermentans and Mycoplasma salivarium. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002;46:667–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Di Virgilio F, et al. Nucleotide receptors: an emerging family of regulatory molecules in blood cells. Blood. 2001;97:587–600. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang L, Jacobsen SE, Bengtsson A, Erlinge D. P2 receptor mRNA expression profiles in human lymphocytes, monocytes and CD34+ stem and progenitor cells. BMC Immunol. 2004;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Leal DB, et al. Characterization of NTPDase (NTPDase1; ectoapyrase; ecto-diphosphohydrolase; CD39; EC3.6.1.5) activity in human lymphocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1721:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee DH, Park KS, Kong ID, Kim JW, Han BG. Expression of P2 receptors in human B cells and Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines. BMC Immunol. 2006;7:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-7-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Beldi G, et al. Deletion of CD39 on natural killer cells attenuates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Hepatology. 2010;51:1702–1711. doi: 10.1002/hep.23510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Padeh S, Cohen A, Roifman CM. ATP-induced activation of human B lymphocytes via P2-purinoceptors. J. Immunol. 1991;146:1626–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sakowicz-Burkiewicz M, Kocbuch K, Grden M, Szutowicz A, Pawelczyk T. Adenosine 5'-triphosphate is the predominant source of peripheral adenosine in human B lymphoblasts. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010;61:491–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gorini S, et al. ATP secreted by endothelial cells blocks CX3CL1-elicited natural killer cell chemotaxis and cytotoxicity via P2Y11 receptor activation. Blood. 2010 Jul 28; doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-260828. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 20668227 (2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sumi Y, et al. Adrenergic receptor activation involves ATP release and feedback through purinergic receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C1118–C1126. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00122.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Peter C, Wesselborg S, Lauber K. Molecular suicide notes: last call from apoptosing cells. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;2:78–80. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang Q, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Franchi L, Warner N, Viani K, Nuñez G. Function of Nod-like receptors in microbial recognition and host defense. Immunol. Rev. 2009;227:106–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ghiringhelli F, et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells induces IL-1beta-dependent adaptive immunity against tumors. Nat. Med. 2009;15:1170–1178. doi: 10.1038/nm.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Boeynaems JM, Communi D. Modulation of inflammation by extracellular nucleotides. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2006;126:943–944. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Di Virgilio F, Boeynaems JM, Robson SC. Extracellular nucleotides as negative modulators of immunity. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2009;9:507–713. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kaufmann A, et al. “Host tissue damage” signal ATP promotes non-directional migration and negatively regulates toll-like receptor signaling in human monocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:32459–32467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505301200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Duhant X, Schandené L, Bruyns C, Gonzalez NS, Goldman M, Boeynaems JM, Communi D. Extracellular adenine nucleotides inhibit the activation of human CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2002;169:15–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen Y, Shukla A, Namiki S, Insel PA, Junger WG. A putative osmoreceptor system that controls neutrophil function through the release of ATP, its conversion to adenosine, and activation of A2 adenosine and P2 receptors. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004;76:245–253. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen Y, Hashiguchi N, Yip L, Junger WG. Hypertonic saline enhances neutrophil elastase release through activation of P2 and A3 receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1051–C1059. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00216.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yip L, Cheung CW, Corriden R, Chen Y, Insel PA, Junger WG. Hypertonic stress regulates T-cell function by the opposing actions of extracellular adenosine triphosphate and adenosine. Shock. 2007;27:242–250. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000245014.96419.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mizumoto N, Kumamoto T, Robson SC, Sévigny J, Matsue H, Enjyoji K, Takashima A. CD39 is the dominant Langerhans cell-associated ecto-NTPDase: modulatory roles in inflammation and immune responsiveness. Nat. Med. 2002;8:358–365. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Stagg J, Smyth MJ. Extracellular adenosine triphosphate and adenosine in cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:5346–5358. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Otha A, et al. A2A adenosine receptor protects tumors from antitumor T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:13132–13137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605251103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ohtsuka T, et al. Ecto-5'-nucleotidase (CD73) attenuates allograft airway rejection through adenosine 2A receptor stimulation. J. Immunol. 2010;185:1321–1329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sevigny CP, et al. Activation of adenosine 2A receptors attenuates allograft rejection and alloantigen recognition. J. Immunol. 2007;178:4240–4249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Deaglio S, et al. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1257–1265. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sun X, et al. CD39/ENTPD1 expression by CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells promotes hepatic metastatic tumor growth in mice. Gastroenterology. Sep. 2010;139(3):1030–40. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.007. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Inoue Y, Chen Y, Hirsh MI, Yip L, Junger WG. A3 and P2Y2 receptors control the recruitment of neutrophils to the lungs in a mouse model of sepsis. Shock. 2008;30:173–177. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318160dad4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fredholm BB. Adenosine receptors as drug targets. Exp. Cell Res. 2010;316:1284–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Price MJ. Bedside evaluation of thienopyridine antiplatelet therapy. Circulation. 2009;119:2625–2632. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.696732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kam PC, Nethery CM. The thienopyridine derivatives (platelet adenosine diphosphate receptor antagonists), pharmacology and clinical developments. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:28–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.02960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]