Abstract

A novel La (III) complex, [LaL(H2O)3]NO3 ·3H2O, with Schiff base ligand L derived from kaempferol and diethylenetriamine, has been synthesized and characterized by elemental analysis, IR, UV-visible, 1H NMR, thermogravimetric analysis, and molar conductance measurements. The fluorescence spectra, circular dichroism spectra, and viscosity measurements and gel electrophoresis experiments indicated that the ligand L and La (III) complex could bind to CT-DNA presumably via intercalative mode and the La (III) complex showed a stronger ability to bind and cleave DNA than the ligand L alone. The binding constants (K b) were evaluated from fluorescence data and the values ranged from 0.454 to 0.659 × 105 L mol−1 and 1.71 to 17.3 × 105 L mol−1 for the ligand L and La (III) complex, respectively, in the temperature range of 298–310 K. It was also found that the fluorescence quenching mechanism of EB-DNA by ligand L and La (III) complex was a static quenching process. In comparison to free ligand L, La (III) complex exhibited enhanced cytotoxic activities against tested tumor cell lines HL-60 and HepG-2, which may correlate with the enhanced DNA binding and cleaving abilities of the La (III) complex.

1. Introduction

The metal-based anticancer complexes have attracted many bioinorganic chemists' interest since the success of platinum complexes as anticancer agents [1–3]. Among various metal complexes, La (III) complexes have been intensively investigated due to their more physiological activities and lower toxicities after coordination with ligand. People have paid great interest to synthesis, DNA interaction, and anticancer activity of La (III) complexes in recent years [4–8].

In order to develop novel metal-based anticancer drugs, a new strategy has been adopted in the designs of antitumor coordination compounds based on the traditional Chinese medicines as ligands. A large number of the traditional Chinese medicines have been screened and used for treating and preventing various chronic conditions over long-term folk practice [9, 10]. Flavonoids are a group of naturally occurring compounds that are found in many high plants. Such compounds have been evoked widespread interest in biological and pharmacological activities including antioxidant, anticancer, and antimicrobial, and so forth [11–15]. Moreover, most of flavonoids are strong metal chelators because hydroxy and oxo groups in flavonoid structure have the ability to form complexes with various metal ions, and their biological activities are influenced by the presence of metal ions. The metal complexes derived from such best known flavonoids as quercetin, morin, naringenin, and hesperetin have been extensively studied in recent years [16–21]. Kaempferol (3, 3′, 5, 7-tetrahydroxyflavone), one of the most abundant natural flavonoids, is found in berries, tea, Brassica and Allium species, and many traditional Chinese herbal medicines (Scheme 1(a)). It is also an attractive reagent due to extensive pharmacological activities [22, 23]. However, to the best of our knowledge, less attention was paid to the DNA interaction and antitumor activities of rare earth metal complexes derived from kaempferol [24]. In this work, we synthesized and characterized a novel La (III) complex with Schiff base ligand derived from kaempferol and diethylenetriamine and focused our attention on comparative studies of DNA binding, DNA cleavage, and in vitro antitumor activities of Schiff base ligand L (Scheme 1(b)) and its La (III) complex.

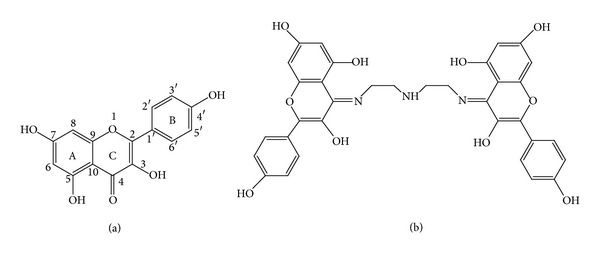

Scheme 1.

Kaempferol (a) and Schiff base ligand L derived from kaempferol and diethylenetriamine (b).

2. Experiment

All the chemicals were of analytical grades and used without further purification. The concentration of calf thymus DNA (CT-DNA) was determined by UV absorption at 260 nm using a molar absorption coefficient ε 260 = 6600 L mol−1 cm−1. Purity of CT-DNA was checked by monitoring the ratio of the absorbance at 260 and 280 nm. The solution gave a ratio of >1.8 at A 260/A 280, indicating that DNA was sufficiently free from protein.

Elemental analyses were performed using a Carlo-Elba1106 elemental analytic instrument (Italy). The IR spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50 FT-IR spectrometer (America) as KBr pellets in the range of 4,000–400 cm−1 region. 1H NMR spectral data were measured on a Varian INOVA-400 spectrometer (Switzerland) with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard. Fluorescence spectra were recorded on an F-7000 spectrophotometer (Japan). Thermogravimetric analysis (TG) was carried out on a SDT Q600 (America) instrument under argon, using α-alumina as a reference compound, from room temperature to 800°C at heating rate of 15°C min−1. UV-Visible spectra were measured on TU-1901 spectrophotometer (China). Circular dichroism measurements were carried out on a Jasco-815 spectrometer. Conductivity measurement was performed at room temperature using a DDS-11A conductivity meter (China).

2.1. Synthesis of Schiff Base Ligand L

Schiff base ligand L was synthesized according to the following procedure [25]. Diethylenetriamine (1 mmol) and kaempferol (0.578 g, 2 mmol) were dissolved in ethanol (10 mL). The solution was refluxed for 3 h. The yellow precipitate was filtered off, washed with ethanol, and dried in vacuum. Anal. Calc. for C34H33N3 O12: C, 60.44; H, 4.92, N, 6.22%. Found: C, 60.15; H, 4.96; N, 6.16%. IR (KBr, cm−1): 3318, 3116, 1659, 1569, 1505, 1312, 1177, 823. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.55–2.68 (m, 8H), 6.01 (s, 2H), 6.24 (s, 2H), 6.88-6.89 (d, 4H), 8.01–8.03 (d, 4H).

2.2. Synthesis of La (III) Complex

The Schiff base ligand L (0.34 g, 0.5 mmol) was dissolved in acetone (20 mL) and triethylamine (130 μL, 1 mmol) was added. After 5 min, La (III) nitrate (0.217 g, 0.5 mmol) was added quickly and the solution was refluxed for 4 h. A brown precipitate was filtered off, washed with ethanol, and dried in vacuum. Anal. Calc. for C34H39LaN4O19: C, 43.14; H, 4.15; N, 5.92%. Found: C, 41.67; H, 4.12; N, 5.84%. IR (KBr, cm−1): 3380, 2348, 1606, 1384, 1265, 1172, 887, 511. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 2.66–2.85 (m, 8H), 5.69 (s, 2H), 5.93 (s, 2H), 6.84–6.87 (d, 4H), 8.38–8.42 (d, 4H).

2.3. DNA Binding and Cleavage Experiments

Fluorescence quenching experiments were carried out by adding the increasing amounts of compounds (0, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 μM) to EB-DNA system (CEB = 50 μM, CDNA = 200 μM, 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer solution, pH = 7.4). The fluorescence spectra were measured at three different temperatures (298, 303, and 310 K). Emission spectra were carried out in 3 mL quartz cuvette with 339 nm excitation light, and emission was measured at 590 nm.

Viscosity experiments were carried on an Ubbelohde viscometer, immersed in a thermostated water bath maintained at 25°C. The concentration of DNA was 100 μM in buffer solution (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4). Data were presented as (η/η 0)1/3 versus the concentration of the complexes, whereη is the viscosity of DNA in the presence of compounds (4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 28 μM) and η 0 is the viscosity of DNA alone.

Circular dichroism (CD) absorption spectra of DNA were measured in buffer solution (0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) at a 50 nm/min scan rate in the wavelength range from 220 to 300 nm, with 100 μM DNA in the absence and presence of the compounds (20 μM). All experiments were done using a quartz cell of 1 mm path length. The spectra were recorded at 25°C after the compounds had been incubated with CT-DNA for 4 h at 37°C.

Plasmid DNA (pUC 19) cleavage activity of the compounds was monitored by using agarose gel electrophoresis. In a typical experiment, supercoiled DNA (pUC 19) (50 g/mL, 5 μL) in Tris-HCl (100 mM, pH 7.4) was treated with concentrations (100 μM) of different compounds, followed by dilution with the Tris-HCl buffer to a total volume of 20 μL. The samples were then incubated at 37°C and loaded on a 0.1% agarose gel containing 1.0 g/mL of ethidium bromide. Electrophoresis was carried out at 80 V for 40 min in TAE buffer and run in duplicate. Bands were visualized by UV light and photographed.

2.4. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

Cytotoxicities of all the compounds against HL-60 (human leukemia cell) and HepG-2 (liver hepatocellular carcinoma cell) were determined by WST-8 assay (WST-8 sodium2-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-phenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2, 4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium) with cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8). The cells were plated in 96-well culture plates at density of 1 × 104 cells per well and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a water-atmosphere (5% CO2). The tested compounds with various concentrations (0, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μM) were obtained by dissolving them in DMSO and diluting them with culture medium (DMSO final concentration < 1%). Then the diluted solution of compounds was treated with the cells for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After that, 10 μL of a freshly diluted CCK-8 solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well for 2 h. The cell survival was evaluated by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm. The IC50 which inhibits growth of 50% of cells relative to nontreated control cells was calculated as the concentration of tested compound. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization

The molar conductivity of the La (III) complex is 115 S cm2 mol−1 in DMF solution, indicating the electrolytic nature of the complex. The TG curve of complex shows a series of weight loss upon heating. The first weight loss 5.88% (calculated 5.71%) is probably assigned to three cocrystallized water molecules by 120°C. The second weight loss 5.56% (calculated 5.71%) in the range of 120–260°C is coincided with the three coordinated water molecules. The elemental analysis, molar conductivity, and TG indicate that formula of the La (III) complex conforms to [LaL(H2O)3]NO3 ·3H2O.

On the comparison of the IR spectra of the La (III) complex with ligand L, the important information on coordination reaction was provided. The characteristic stretching (C=N) mode of ligand L occurs at 1660 cm−1, while, due to the formation of complex, this band appears at about 1606 cm−1. It can be suggested that the La (III) coordination occurs through the imine nitrogen atom. In addition, a characteristic vibration band of free nitrates was observed at about 1384 cm−1 in the spectrum of the complex [21]. The La (III) complex and ligand L were also examined by H NMR spectra, and the chemical shift differences were shown in Table 1. The complex exhibited upfield shifts due to electron transfer from the imine nitrogen and the hydroxyl oxygen atom to La (III). There was a negative shift effect for the H6 and H8 of ring A of the complex and a positive shift effect for the H2′,6′ of ring B of the complex existed. The results suggested that ligand L could be chelated to La (III) ion via both the imine nitrogen and 3-OH of C ring on the basis of the H1 NMR data [9, 26].

Table 1.

1H NMR chemical shift differences between L and the complex.

| Hydrogen site | δ (L) | δ (complex) |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 6.01 | 5.69 |

| 8 | 6.23 | 5.92 |

| 3′, 5′ | 6.88–6.90 | 6.84–6.86 |

| 2′, 6′ | 8.01–8.03 | 8.38–8.42 |

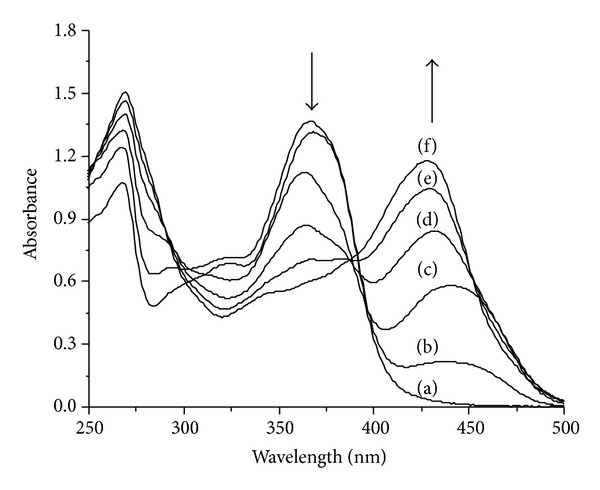

The interactions between ligand L and the La (III) ion were also studied by absorption spectra in order to further understand structure information of the complex. The ligand L absorbed with maxima at 368 nm (band I) and 269 nm (band II). Band I is related to ring B (cinnamoyl system) and band II to ring A (benzoyl system) [27, 28]. Absorption spectra of ligand L in the ethanol solution with different concentrations of La(NO3)3 are shown in Figure 1. The intensity of ligand L (band I) decreased gradually with addition of La (III) to the solution and a new absorbance peak appeared at 427 nm. The results indicated that ligand L could form complex with La (III). The appeared new peak at 427 nm suggested that La (III) had bonded to 3-hydroxyl and C=N of ring C. Band I bathochromic shift can be explained by the interaction of La (III) with the 3-hydroxyl group of ring C producing an electronic redistribution between ligand L and La (III), which resulted in an extended π-bonding system. The 5-OH group is not involved due to lesser proton acidity and the steric hindrance caused by the first complexation [18, 24].

Figure 1.

Absorption spectra of ligand L in ethanol in the presence of La (III). The molar ratios [La(NO3)3]/[ligand] = 0 (a), 0.2 (b), 0.4 (c), 0.6 (d), 0.8 (e), and 1.0 (f).

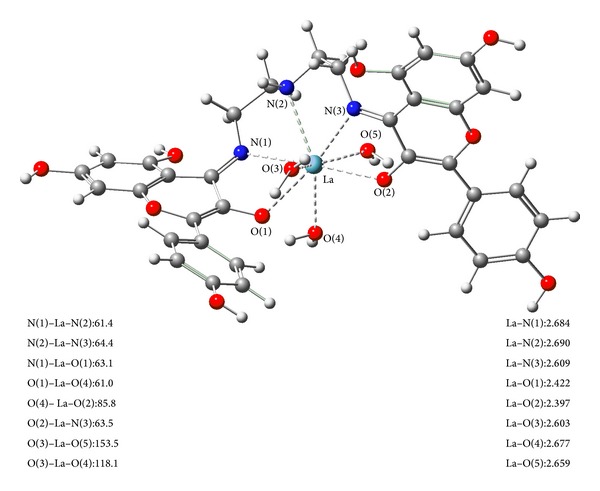

Since no single crystals suitable for X-ray determination could be isolated, structural information for the La (III) complex was also obtained from the B3LYP optimization calculations, as shown in Figure 2. Theory calculation result was in good agreement with above studies.

Figure 2.

The optimized structure of the La (III) complex. The sky blue ball is for La atom, the red balls are for oxygen atoms, the blue balls are for nitrogen atoms, the gray balls for carbon atoms, and the white balls are for hydrogen atoms. Bond lengths are in angstrom and bond angles are in degree.

3.2. DNA Binding and Cleavage Studies

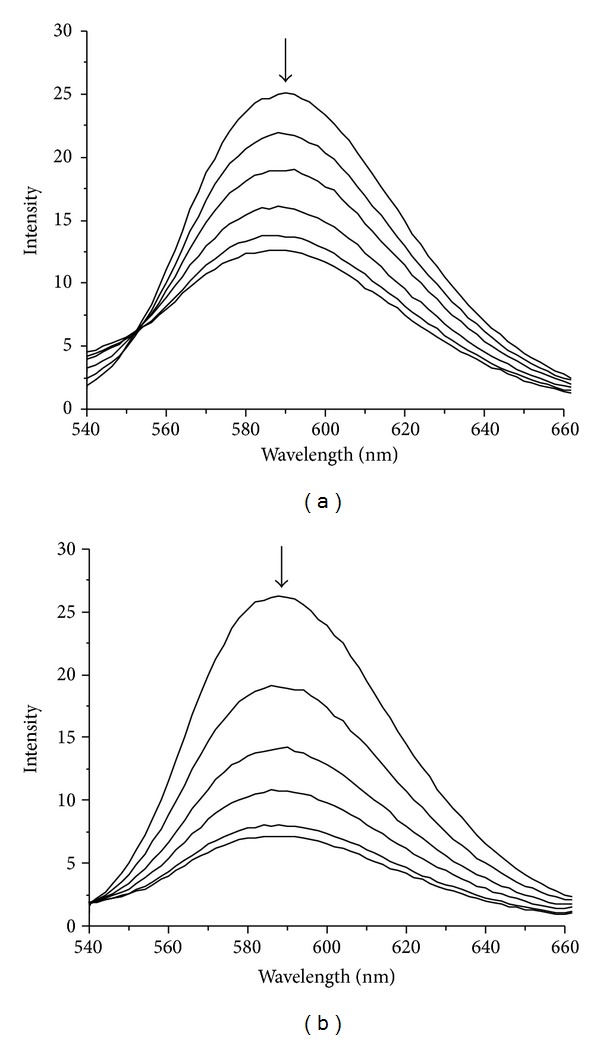

Since DNA is the primary intracellular target of anticancer drugs, the interaction studies of drugs with DNA are very important in the development of new therapeutic reagents. Binding abilities of ligand L and La (III) complex to CT-DNA were investigated by EB-competitive binding experiments. Ethidium bromide (EB) has weak fluorescence, but its emission intensity in the presence of DNA could be greatly enhanced because of its strong intercalation between the adjacent DNA base pairs on the double helix. It was previously reported that this enhanced fluorescence could be quenched, at least partly by the addition of a competing agent [29, 30]. The emission spectra of EB bound to CT-DNA in the absence and presence of ligand L and La (III) complex are shown in Figure 3, respectively. The addition of ligand L and La (III) complex to DNA solutions pretreated with EB caused appreciable decrease in the emission intensity, which indicated that ligand L and La (III) complex competed with EB in binding to DNA through intercalative mode.

Figure 3.

Emission spectra of DNA-EB with various concentrations of ligand L (a) and La (III) complex (b) at 298 K, [EB] = 50 μM, [DNA] = 200 μM, and [compound] = 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 μM, respectively. The arrow shows the intensity changes on increasing the compound concentration.

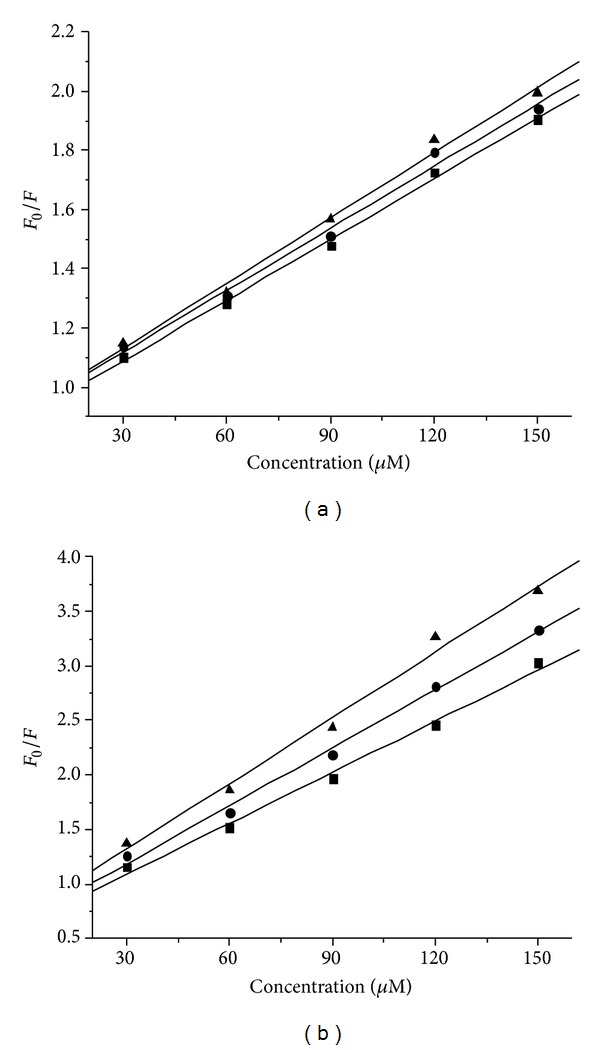

The mechanisms of fluorescence quenching are classified as either dynamic or static quenching, which can be distinguished by their different dependences on temperatures. Generally, the fluorescence quenching was analyzed according to the Stern-Volmer equation [31] as follows:

| (1) |

where F 0 and F are the fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of the compound, respectively. K SV is a linear Stern-Volmer quenching constant, K q is the quenching rate constant, τ 0 is the average lifetime of molecules in the absence of quencher and its value is about 10−8 s [32], and [Q] is the concentration of the compound. The Stern-Volmer plots of F 0/F versus [Q] at three different temperatures are presented in Figure 4. The values of K SV are listed in Table 2. The values of K SV decreased with the increasing temperatures, and the values of K q were much larger than the limiting diffusion constant of the biomacromolecules (2.0 × 1010 L mol−1 s−1) [33]. The results suggested that the quenching mechanism of the system was a static quenching process.

Figure 4.

Stern-Volmer plots for the fluorescence quenching of DNA-EB system by ligand L (a) and La (III) complex (b) at different temperatures, (▲) 298 K; (●) 303 K; (■), 310 K.

Table 2.

The Stern-Volmer quenching constants of system at various temperatures.

| Compound | T (K) | K SV (104 L mol−1) | K q (1012 L mol−1 s−1) | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand L | 298 | 0.734 | 0.734 | 0.9966 |

| 303 | 0.697 | 0.697 | 0.9956 | |

| 310 | 0.684 | 0.684 | 0.9985 | |

|

| ||||

| La complex | 298 | 2.01 | 2.01 | 0.9950 |

| 303 | 1.77 | 1.77 | 0.9976 | |

| 310 | 1.56 | 1.56 | 0.9966 | |

R is the correlation coefficient.

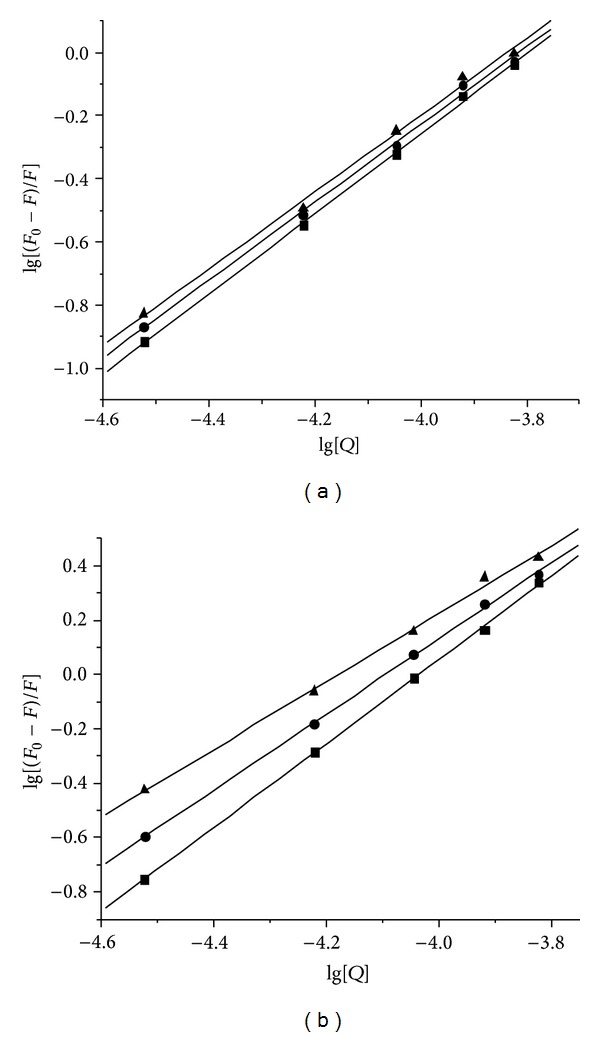

For a static quenching process, the binding constant (K b) and the number (n) of binding sites for ligand L and La (III) complex with DNA can be determined by the following equation [34]:

| (2) |

where K b and n are the binding constant and the number of binding sites in base pairs, respectively. The plots of lg[(F 0 − F)/F] versus lg[Q] were showed in Figure 5, and the values of K b and n were listed in Table 3. The binding constant K b increased with the increasing temperature, indicating that rising temperature contributed to the binding of ligand L and La (III) complex with DNA and the La (III) complex has much stronger binding ability than ligand L. Compared to the binding constant of EB with DNA (5.16 × 105 L mol−1) [35], the ligand L and La (III) complex could compete against EB and replace the intercalated EB from the DNA-EB complex system.

Figure 5.

Plots of lg[(F 0 − F)/F] versus lg[Q] for the fluorescence quenching of DNA-EB system by ligand L (a) and La (III) complex (b) at different temperatures, (▲) 298 K; (●) 303 K; (■), 310 K.

Table 3.

The binding constants and binding sites at various temperatures.

| Compound | T (K) | K b (105 L mol−1) | n | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand L | 298 | 0.454 | 1.21 | 0.9983 |

| 303 | 0.504 | 1.23 | 0.9985 | |

| 310 | 0.659 | 1.27 | 0.9995 | |

|

| ||||

| La complex | 298 | 1.71 | 1.25 | 0.9984 |

| 303 | 5.33 | 1.40 | 0.9996 | |

| 310 | 17.3 | 1.54 | 0.9998 | |

R is the correlation coefficient.

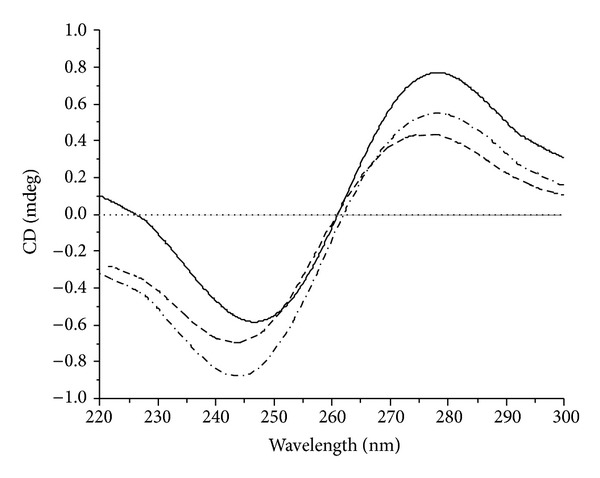

CD spectroscopy is useful in monitoring the conformational variations of DNA in the presence of drug in solution. CD spectral variations of CT-DNA in the absence and presence of the ligand L and La (III) complex were given in Figure 6, respectively. The free CT-DNA exhibits two conservative CD bands, a positive band at 275 nm due to base stacking and a negative band at 245 nm due to right-handed helicity which is characteristic of DNA in the right-handed B form [36]. When the ligand L and La (III) complex are incubated with CT-DNA, the CD spectra of CT-DNA undergo significant variations in both positive and negative bands in intensity. The results suggested that the ligand L and La (III) complex could induce disturbance on DNA base stacking and on DNA right-handed helicity. The arrangement of the DNA bases is somewhat altered, and the characteristics of the B form CD spectrum are still conserved. These changes further confirm the intercalative binding of the ligand L and La (III)complex with CT-DNA [37, 38].

Figure 6.

CD spectra of CT-DNA (100 μM) in the absence and presence of the compounds (20 μM). The solid line is for DNA alone, the short dash line for DNA + ligand L, and the dash line for DNA + La (III) complex.

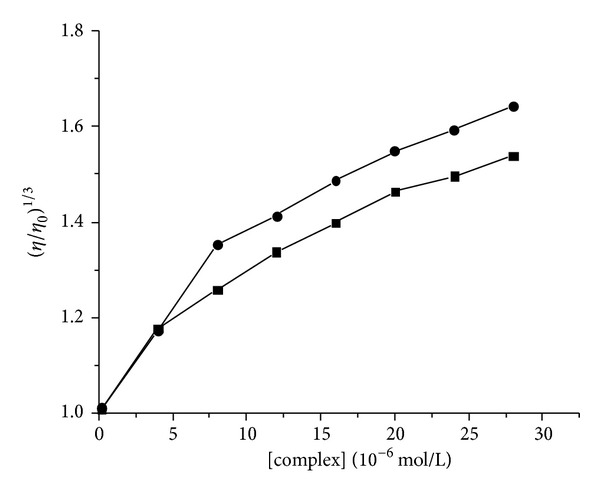

In addition to spectroscopic data, the viscosity measurement of CT-DNA is also an effective tool to study the binding mode of the compound to DNA in the absence of crystallographic structural data and NMR. A classical intercalative mode would cause elongation of DNA polymer as base pairs were separated to accommodate the bound compound, resulting in an increase in its viscosity. In contrast, a partial and/or nonclassical intercalation of compound may bend (or kink) the DNA helix resulting in a decrease in its effective length, reducing its viscosity concomitantly [39, 40]. The effects of ligand L and La (III) complex on the viscosity of CT-DNA were given in Figure 7. It could be seen that the relative viscosity of DNA increased steadily with increasing concentrations of ligand L and La (III) complex, respectively. The results revealed that ligand L and La (III) complex could intercalate between adjacent DNA base pairs, causing an extension in the helix and increase in viscosity of the DNA. The results were consistent with the above spectral results.

Figure 7.

Effects of increasing concentrations of ligand L (●) and La (III) complex (■) on the viscosity of CT-DNA, [DNA] = 100 μM, [compound] = 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 28 μM, respectively.

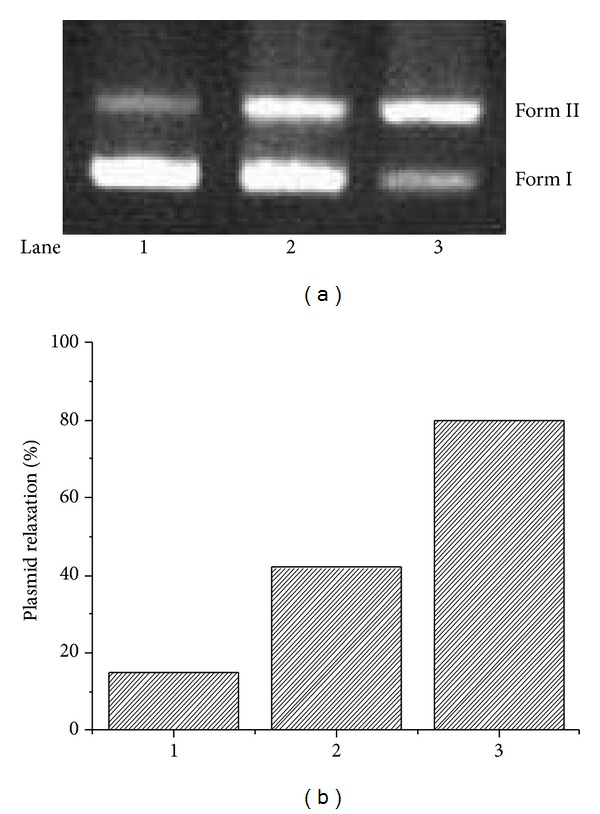

The abilities of ligand L and La (III) complex in inducing DNA cleavage were further investigated by gel electrophoresis using plasmid DNA (pUC 19) in the absence of external reagent or light. The DNA cleavage was analyzed by monitoring the conversion of supercoiled circular DNA (form I) to nicked circular DNA (Form II) under physiological conditions. The amounts of strand scission were assessed by an agarose gel electrophoresis. Figure 8 showed the relative cleavage efficiency of ligand L and La (III) complex. It was obvious that La (III) complex showed more efficient DNA cleavage ability than ligand L.

Figure 8.

Effect of different compounds (100 μM) on the cleavage reactions of pUC 19 DNA (12.5 μg/mL) in a Tris-HCl buffer (100 mM, pH 7.4) at 37°C for 4 h. (a) Agarose gel electrophoresis diagram: lane 1, DNA control; lane 2, ligand L; lane 3, La (III) complex. (b) Quantitation of % plasmid relaxation (Form II %) relative to plasmid DNA per lane.

3.3. Antitumor Activity

To compare antitumor activities of La (III) complex, ligand L, and La (III) nitrate, the cytotoxic activities of all compounds were tested by means of CCK-8 assay against the proliferation of HL-60 and HepG-2 cell lines. The results of cytotoxic activities against tumor cells are expressed as IC50 values and are presented in Table 4. The La (III) complex showed higher cytotoxic activities than ligand L and La (III) nitrate according to the IC50 values of the tested compounds in Table 4, which may be attributed to the extended π-bonding system resulting from the chelation of the metal ion with the ligand L [20]. Furthermore, the La (III) complex was more potent than the 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) against the HL-60 tumor cell line.

Table 4.

IC50 values of the tested compounds against tumor cell lines.

| Cell line | IC50 value (μM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| La (III) complex | Ligand L | La (III) nitrate | 5-FU | |

| HL-60 | 22.37 ± 0.93 | 32.49 ± 1.12 | >100 | 37.59 ± 1.51 |

| HepG-2 | 17.12 ± 1.06 | 24.39 ± 1.20 | 47.16 ± 2.65 | 6.78 ± 0.65 |

5-FU was used as control.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a novel La (III) complex with Schiff base ligand derived from kaempferol and diethylenetriamine has been prepared and characterized. The ligand L and its La (III) complex interacted with DNA by intercalation mode, and La (III) complex has much stronger DNA binding and cleaving abilities than ligand L. The results of in vitro cytotoxic activities against HL-60 and HepG-2 cell lines indicated that the La (III) complex exhibited more effective cytotoxic activities than the ligand L, which may correlate with the enhanced DNA binding and cleavage abilities of the La (III) complex.

Acknowledgment

This study was financially supported by the National Science Foundation of China (nos. 21172182, 21362026, and 21163003).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Junicke SH, Bruhn C. Carbohydrates coordinated to platinum(IV) through hydroxyl groups: a new class of platinum complexes with bioactive ligands. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 1997;36(23):2686–2688. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo ZJ, Sadler PJ. Metals in medicine. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 1999;38(11):1512–1531. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990601)38:11<1512::AID-ANIE1512>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fricker SP. The therapeutic application of lanthanides. Chemical Society Reviews. 2006;35(6):524–533. doi: 10.1039/b509608c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biba F, Groessl M, Egger A, Roller A, Hartinger CG, Keppler BK. New insights into the chemistry of the antineoplastic lanthanum complex tris(1,10-phenanthroline)tris(thiocyanato-κN)lanthanum(III) (KP772) and its interaction with biomolecules. European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2009;2009(28):4282–4287. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kostova I, Momekov G, Zaharieva M, Karaivanova M. Cytotoxic activity of new lanthanum (III) complexes of bis-coumarins. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;40(6):542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kostova I, Momekov G. New cerium(III) complexes of coumarins—synthesis, characterization and cytotoxicity evaluation. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;43(1):178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulkarni A, Patil SA, Badami PS. Synthesis, characterization, DNA cleavage and in vitro antimicrobial studies of La(III), Th(IV) and VO(IV) complexes with Schiff bases of coumarin derivatives. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;44(7):2904–2912. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JG, Qiao X, Gao YC, et al. Synthesis, DNA binding, photo-induced DNA cleavage and cell cytotoxicity studies of a family of light rare earth complexes. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2012;109:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen F-Z, Tan X-M, Liu C-Y, et al. Synthesis, characterization and preliminary cytotoxicity evaluation of five Lanthanide(III)-Plumbagin complexes. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2011;105(3):426–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z-F, Liang H. Progresses in TCM metal-based antitumour agents. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;10(5):412–423. doi: 10.2174/1871520611009050412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanakis CD, Tarantilis AP, Polissiou MG. An overview of DNA and RNA bindings to antioxidant flavonoids. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2007;49:29–36. doi: 10.1007/s12013-007-0037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nijveldt RJ, van Nood E, van Hoorn DEC, Boelens PG, van Norren K, van Leeuwen PAM. Flavonoids: a review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2001;74(4):418–425. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dugas JA, Castaneda-Acosta J, Bonin GCJ. Evaluation of the total peroxyl radical-scavenging capacity of flavonoids: structure-activity relationships. Journal of Natural Products. 2000;63:327–331. doi: 10.1021/np990352n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dehghan G, Shafiee A, Ghahremani MH, Ardestani SK, Abdollahi M. Antioxidant potential of various extracts from Ferula szovitsiana in relation to their phenolic content. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2007;45(9):691–699. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thapa M, Kim Y, Desper J, Chang K-O, Hua DH. Synthesis and antiviral activity of substituted quercetins. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2012;22(1):353–356. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.10.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J, Wang FL, Wang YJ, Tang N. Synthesis, characterization, antioxidative and antitumor activities of solid quercetin rare earth(III) complexes. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2001;83:41–48. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan J, Wang CB, Zhu LC. DNA binding, cytotoxicity, apoptotic inducing activity, and molecular modeling study of quercetin zinc (II) complex. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;17(2):614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dehghan G, Khoshkam Z. Tin(II)-quercetin complex: synthesis, spectral characterisation and antioxidant activity. Food Chemistry. 2012;131(2):422–426. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopacz M, Woznicka E, Gruszecka J. Antibacterial activity of morin and its complexes with La (III), Gd (III) and Lu (III) ions. Acta Potoniae Pharmaceutica-Drug Research. 2005;62(1):65–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang BD, Yang ZY, Wang Q, Cai TK, Crewdsonc P. Synthesis, characterization, cytotoxic activities, and DNA-binding properties of the La(III) complex with Naringenin Schiff-base. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;14(6):1880–1888. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Yang YZ, Wang MF. Synthesis, characterization, DNA binding properties and antioxidant activity of Ln(III) complexes with hesperetin-4-one-(benzoyl) hydrazone. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;44:4585–4595. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bestwick CS, Milne L, Pirie L, Duthie SJ. The effect of short-term kaempferol exposure on reactive oxygen levels and integrity of human (HL-60) leukaemic cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: Molecular Basis of Disease. 2005;1740(3):340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bestwick CS, Milne L, Duthie SJ. Kaempferol induced inhibition of HL-60 cell growth results from a heterogeneous response, dominated by cell cycle alterations. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2007;170(2):76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang GW, Guo JB, Zhao N, Wang JR. Study of interaction between kaempferol-Eu3+ complex and DNA with the use of the Neutral Red dye as a fluorescence probe. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2010;144(1):239–246. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang XB, Wang Q, Huang Y, Fu PH, Zhang SJ, Zeng RQ. Synthesis, DNA interaction and antimicrobial activities of copper (II) complexes with Schiff base ligands derived from kaempferol and polyamines. Inorganic Chemistry Communications. 2012;25:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manolova I, Kostovab I, Konstantinovc S, Karaivanovac M. Synthesis, physicochemical characterization and cytotoxic screening of new complexes of cerium, lanthanum and neodymium with Niffcoumar sodium salt. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1999;34(10):853–858. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang J, Liu Y, Xie XM, Li S, Jiang M, Wang YD. Interactions of human serum albumin with chlorogenic acid and ferulic acid. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2004;1674:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bukhari SB, Memon S, Mahroof-Tahir M, Bhanger MI. Synthesis, characterization and antioxidant activity copper-quercetin complex. Spectrochimica Acta A. 2009;71(5):1901–1906. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuwabara M, Yoon C, Goyne T, Thederahn T, Sigman DS. Nuclease activity of 1,10-phenanthroline-copper ion: reaction with CGCGAATTCGCG and its complexes with netropsin and EcoRI. Biochemistry. 1986;25(23):7401–7408. doi: 10.1021/bi00371a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thederahn T, Spassky A, Kuwabara MD. Chemical nuclease activity of 5-phenyl-1,10-phenanthroline-copper ion detects intermediates in transcription initiation by E. Coli RNA polymerase. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1990;168:756–762. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)92386-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eftink MR, Ghiron CA. Fluorescence quenching studies with proteins. Analytical Biochemistry. 1981;114(2):199–227. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lakowicz JR, Weber G. Quenching of fluorescence by oxygen: a probe for structural fluctuations in macromolecules. Biochemistry. 1973;12(21):4161–4170. doi: 10.1021/bi00745a020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva D, Cortez CM, Louro SRW. Chlorpromazine interactions to sera albumins: a study by the quenching of fluorescence. Spectrochimica Acta A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2004;60(5):1215–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang M, Xie XM, Zheng D, Liu Y, Li YX, Chen XJ. Spectroscopic studies on the interaction of cinnamic acid and its hydroxyl derivatives with human serum albumin. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2004;692:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geng S, Liu G, Li W, Cui F. Molecular interaction of ctDNA and HSA with sulfadiazine sodium by multispectroscopic methods and molecular modeling. Luminescence. 2013;28(5):785–792. doi: 10.1002/bio.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collins JG, Shields TP, Barton JK. 1H-NMR of Rh(NH3)4phi3+ bound to d(TGGCCA)2: classical intercalation by a nonclassical octahedral metallointercalator. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1994;116(22):9840–9846. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norden B, Tjerneld F. Structure of methylene blue-DNA complexes studied by linear and circular dichroism spectroscopy. Biopolymers. 1982;21(9):1713–1734. doi: 10.1002/bip.360210904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabatabaee M, Bordbar M, Ghassemzadeh M, et al. Two new neutral copper(II) complexes with dipicolinic acid and 3-amino-1H-1,2,4-triazole formed under different reaction conditions: Synthesis, characterization, molecular structures and DNA-binding studies. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;70:364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lerman LS. Structural considerations in the interaction of DNA and acridines. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1961;3:18–30. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(61)80004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satyanarayana S, Dabrowiak CJ, Chairs JB. Tris(phenanthroline)ruthenium(II) enantiomer interactions with DNA: Mode and specificity of binding. Biochemistry. 1993;32(10):2573–2583. doi: 10.1021/bi00061a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]