Abstract

Aims

Diabetic ketoacidosis is a potentially life threatening complication of diabetes which has a strong relationship to HBA1c. We examined how socioeconomic group affected the likelihood of admission to hospital for diabetes ketoacidosis.

Methods

The Scottish Care Information – Diabetes Collaboration, a dynamic national register of all cases of diagnosed diabetes in Scotland, was linked to national data on hospital admissions. We identified 24,750 people with type 1 diabetes during January 2005 to December 2007. We assessed the relationship between HbA1c and quintiles of deprivation with hospital admissions for diabetes ketoacidosis in people with type 1 diabetes adjusting for patient characteristics.

Results

We identified 23,479 people with type 1 diabetes who had complete recording of covariates. Deprivation had a substantial effect on odds of diabetes ketoacidosis admission (odds ratio 4.51, 95% confidence interval 3.73-5.46 in the most deprived quintile compared with the least deprived). This effect persisted after the inclusion of HbA1c and other risk factors (OR 2.81, 95%CI 2.32-3.39). Males had a reduced risk of diabetes ketoacidosis admission (OR 0.71, 95%CI 0.63-0.79) and those with a history of smoking increased odds of diabetes ketoacidosis admission by 1.55 (95%CI 1.36-1.78).

Conclusion

Females, smokers, those with high HbA1c and living in more deprived areas have an increased risk of diabetes ketoacidosis admission. The effect of deprivation was present even after inclusion of other risk factors. This work highlights that those in poorer areas of the community with high HbA1c represent a group who might be usefully supported to try to reduce admissions.

Keywords: deprivation, diabetes, diabetic ketoacidosis, HbA1c, record linkage

We have previously demonstrated that, among people with type 1 diabetes, HbA1c is an important indicator of risk of admission independently of other predictors with a particularly strong relationship to admissions coded as diabetic ketoacidosis [1]. Deprivation is a further important potential indicator of disease risk in the population, however previous analysis of data from a smaller Scottish population suggests that deprivation has a relatively weak relationship with HbA1c in people with type 1 diabetes [2].

This study examines how socioeconomic group affects likelihood of admission to hospital for diabetes ketoacidosis among people with type 1 diabetes, and whether this relationship is explained by HbA1c.

Research Design and Methods

Data

The Scottish Care Information – Diabetes Collaboration (SCI-DC) database is a dynamic national clinical information system of all diagnosed cases of diabetes in Scotland (www.diabetesinscotland.org.uk). SCI-DC contains records for over 99% of diagnosed cases of diabetes [3] with detailed clinical information including body mass index (BMI), creatinine, age, sex, and HbA1c. HbA1c was measured using a variety of clinical methods, all of which were DCCT aligned. Type 1 diabetes was identified using an algorithm which incorporated age, drug prescription and clinical description of the type of diabetes. Those whose type diagnosis was not known were excluded from the analysis. Deprivation was defined using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation [4], which provides a composite index of relative area deprivation across Scotland. Smoking status was defined as current or ex-smoker.

Information on hospital admissions was obtained using Scottish Morbidity Records (SMR01), national data on hospital admissions from Information Services Division (ISD) of NHS National Services, Scotland. The SMR01 records contain over 95% of Scotland’s hospital admissions and include administrative data and demographic information such as age, gender, and postcode of the patient. Individual episodes of care are recorded within each admission with up to six International Classification of Disease (ICD) diagnosis codes (1997-present: ICD 10th revision).

Data were linked within ISD using probabilistic methods based on name, sex, date of birth and postcode, as previously described [5]. No personal identifiers were released to researchers and all subsequent analyses were conducted on anonymised datasets.

Statistical analysis

The outcome of interest was recording of diabetes ketoacidosis as a reason for admission to hospital at least 180 days after the diagnosis for diabetes. Outcome was determined if ICD codes for diabetes ketoacidosis were present in any position of diagnosis. Parametric relationships between mean HbA1c (as measured between 2005-2007) and diabetes ketoacidosis admission were investigated using the fractional polynomial methods in Stata version 11. Natural log of mean HbA1c was found to provide the best fit to the data. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the association between diabetes ketoacidosis admissions, log mean HbA1c, deprivation quintiles (referent quintile 1, least deprived), and history of smoking. Analysis was adjusted for potential confounding factors including age, sex, previous vascular disease (ICD-9: 410-414, 430-438, 443; ICD-10: I20-I25, I60-I69, I73), creatinine, BMI and diabetes duration.

Results

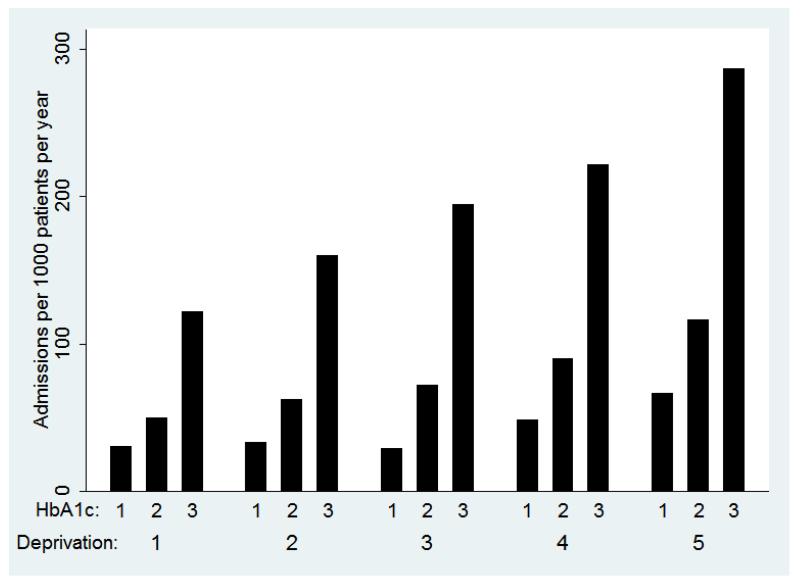

Between January 2005 and December 2007, we identified 24,750 people with type 1 diabetes (Scottish population 5.1million) of whom 23,479 had complete recording of all covariates; 64% were either a current or ex-smoker. There were a total of 4577 admissions coded for diabetes ketoacidosis during the study period (79% of these admissions were single admissions for different people and 21% were multiple admissions). The number of admissions per 1000 persons per year was significantly higher in the most deprived fifth of socioeconomic group (175 admissions per 1000 persons per year compared with 60 admissions per 1000 persons per year in the least deprived fifth). The Figure shows that some of this effect may be explained by HbA1c, but the effect of deprivation is evident in all thirds of HbA1c (range of HbA1c in: tertile 1=4.4-8.15; tertile 2=8.16-9.26; tertile 3=9.27-18.3). Compared to those who did not have an admission mentioning diabetes ketoacidosis, the HbA1c values in those with an admission mentioning diabetes ketoacidosis were greater for all socioeconomic groups

Figure. Number of admissions per 1000 persons per year in groups defined by tertiles of HbA1c (range of HbA1c in: tertile 1=4.4-8.15; tertile 2=8.16-9.26; tertile 3=9.27-18.3) and quintiles of deprivation.

Deprivation was an independent predictor of admission with an increase in odds of admission of 4.51 (95%CI 3.73-5.46) in the most deprived fifth compared to least deprived. After adjustment for HbA1c (expressed as Ln(HbA1c)/0.09531, where one unit increase is equivalent to 10% increase in HbA1c), the increase in odds of admission in all deprivation quintiles was reduced (for most deprived compared to least deprived: OR 3.41; 95%CI 2.54-3.71). After adjusting for the other covariates, younger patients, females (not including maternity admissions), and people with history of vascular disease had a higher risk of admission (Table). History of smoking also had a substantial effect, increasing odds of admission by 1.55 (95%CI 1.36-1.78). The size of the effect of deprivation was reduced by the inclusion of other covariates; however, there remained a substantial increase in odds of admission in the most deprived fifth compared with the least deprived fifth of deprivation (OR 2.82, 95%CI 2.32-3.39).

Table. Coefficients, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals obtained from the logistic regression model for diabetes ketoacidosis admissions.

| Risk factor | Coefficient | Odds ratio (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | −0.348 | 0.71 (0.63-0.79) |

| Age, years a | −0.033 | 0.97 (0.96-0.97) |

| Previous vascular admission | 0.961 | 2.61 (1.96-3.49) |

| Creatinine, μmol/L ab | 0.003 | 1.003 (1.002-1.004) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 ab | −0.059 | 0.94 (0.93-0.95) |

| Diabetes duration, years ab | −0.015 | 0.98 (0.98-0.99) |

| Smoking | 0.439 | 1.55 (1.36-1.78) |

| Ln(HbA1c)/0.09531 ab | 0.458 | 1.58 (1.53-1.63) |

| Deprivation c | ||

| quintile 1 – least deprived | Reference | Reference |

| quintile 2 | 0.266 | 1.31 (1.05-1.62) |

| quintile 3 | 0.515 | 1.67 (1.38-2.03) |

| quintile 4 | 0.691 | 2.00 (1.64-2.42) |

| quintile 5 – most deprived | 1.038 | 2.82 (2.33-3.42) |

Per one unit increase. For ln(HbA1c )/0.09531, equivalent to 10% increase in HbA1c (expressed as %)

Mean of any values recorded between January 2005/date of diagnosis and December 2007/date of death.

Multivariate analysis results for model including all factors in table

Discussion

There was a strong association between deprivation and odds of diabetes ketoacidosis admission with people in more deprived areas having odds of admission 4.5 times higher than those in the least deprived areas. Higher HbA1c also increase the odds of admission. Although the inclusion of HbA1c and other risk factors showed a reduction in the size of the effect of deprivation, a substantial effect remained. This suggests that only some of the effect of deprivation can be explained by these other risk factors in people with type 1 diabetes. Those who have a history of smoking, previous vascular admissions and females also had an increase in risk of admission associated with diabetes ketoacidosis.

We have taken advantage of the linked data for both hospital admissions (SMR-01) and clinical information (SCI-DC), providing almost 100% coverage of all data for people with diagnosed type 1 diabetes in Scotland during 2005-2007. This allowed us to avoid under-reporting in hospital discharge information as found in other studies [6;7]. Some limitations of our study have also been identified. Firstly, an algorithm which incorporated age, drug prescription and clinical description of the type of diabetes was used to determine the type of diabetes. As with nearly all cohorts of this size and type, there is potential for misclassification of diabetes type. However, we believe those misclassified will be an extremely small percentage. Second, we have used the annual average of HbA1c, chosen as the best measure of prevailing HbA1c for each person. This yearly average does not capture the variability of HbA1c and a measurement prior to admission for diabetes ketoacidosis could be argued to be more appropriate. However, HbA1c was measured locally in diabetes clinics during routine clinic visits. Using the last measurement of HbA1c instead of the average did not change the conclusions of our study. Additionally, the number of recordings of HbA1c per person was not significantly associated with odds of admission for diabetes ketoacidosis. Third, in determining the reason for admission we rely on hospital admission data to detect each type of admission. These data are dependent on the accuracy of coding of ICD in hospital diagnosis codes, which is around 90% (see http://www.isdscotland.org/isd/2737.html). However, hyperglycaemia codes are often underused in discharge coding [6]. The codes used do not include people admitted with coma (ICD10 E10.0, E14.0) as these categories include but do not distinguish between, those with ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar or hypoglycaemic coma. We also do not include those with multiple complications potentially including ketoacidosis (ICD10 E10.7, E14.7) since ketoacidosis cannot be separately identified within these codes.

Our results show that people in more deprived areas are at a greater risk of admission for diabetes ketoacidosis, but it is important to discuss why this effect exists. We can speculate that those in more deprived areas have poorer control of their diabetes resulting in increased risk of hospital admission for diabetes ketoacidosis. As discussed, however, deprivation score is not a strong predictor of HbA1c in our population, and much of the effect of deprivation score appears independent of HbA1c.

Despite universal health coverage, free at point of care, social deprivation is also associated with reduced engagement with health services such as retinal screening [8] and deprivation is in turn associated with higher risk of complications [9]. Admission for diabetes ketoacidosis will also relate to other comorbidities, social and medical support and relevant education in diabetes management of during intercurrent illness and other crises. In that context, the relationship with smoking is of interest. This is unlikely to be causal but may be acting as a marker of other health behaviours and thus increased risk of admission for diabetes ketoacidosis.

There is an increasing emphasis on structured education programmes as a means of improving health outcomes in type 1 diabetes. Our analysis shows that socioeconomic group carries risk of diabetes ketoacidosis admission over and above that predicted by HbA1c. An important implication of our work is that where programmes are directed towards prevention of expensive and distressing complications, such as diabetes ketoacidosis, consideration of their relevance to those patients with diabetes who are most at risk (including consideration of socioeconomic group) will be important.

Acknowledgements

These data were available for analysis by members of the Scottish Diabetes Research Network (SDRN) thanks to the hard work and dedication of NHS staff across Scotland who enter the data and people and organisations (the Scottish Care Information –Diabetes Collaboration [SCI-DC] Steering Group, the Scottish Diabetes Group, the Scottish Diabetes Survey Group, the managed clinical network managers and staff in each Health Board) involved in setting up, maintaining and overseeing SCI-DC. The SDRN receives core support from the Chief Scientist’s Office at the Scottish Government Health Department. The costs of data linkage were covered by the Scottish Government Health Department. This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust through the Scottish Health Informatics Programme (SHIP) Grant (Ref WT086113). SHIP is a collaboration between the Universities of Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow and St Andrews and the Information Services Division of NHS Scotland.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CHI

Community Health Index

- ICD

International Classification of Disease

- ISD

Information Services Division

- SCI-DC

Scottish Care Information – Diabetes Collaboration

- SDRN

Scottish Diabetes Research Network

- SHIP

Scottish Health Informatics Programme

- SIMD

Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation

- SMR-01

Scottish morbidity records

Footnotes

Duality of interest: HC has financial relationships with Pfizer, Roche, Astra Zeneca and Eli Lilly. The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Reference List

- 1.Govan L, Wu O, Briggs A, et al. Achieved Levels of HbA1c and Likelihood of Hospital Admission in People With Type 1 Diabetes in the Scottish Population. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1992–1997. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wild SH, McKnight JA, McConnachie A, Lindsay RS. Socioeconomic status and diabetes-related hospital admissions: a cross-sectional study of people with diagnosed diabetes. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2010;64:1022–1024. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.094664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colhoun H, SDRN Epidemiology Group Use of insulin glargine and cancer incidence in Scotland: a study from the Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology Group. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1755–1765. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1453-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scottish Government Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2009: General Report. 2009 http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Statistics/SIMD.

- 5.Wild S, MacLeod F, McKnight J, et al. Impact of deprivation on cardiovascular risk factors in people with diabetes: an observational study. Diabet.Med. 2008;25:194–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anwar H, Fischbacher CM, Leese GP, et al. Assessment of the under-reporting of diabetes in hospital admission data: a study from the Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology Group. Diabet.Med. 2011;28:1514–1519. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leslie PJ, Patrick AW, Hepburn DA, Scougal IJ, Frier BM. Hospital In-patient Statistics Underestimate the Morbidity Associated with Diabetes Mellitus. Diabet.Med. 1992;9:379–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1992.tb01801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leese GP, Boyle P, Feng Z, Emslie-Smith A, Ellis JD. Screening Uptake in a Well-Established Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Program. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2131–2135. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachmann MO, Eachus J, Hopper CD, et al. Socio-economic inequalities in diabetes complications, control, attitudes and health service use: a cross-sectional study. Diabet.Med. 2003;20:921–929. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]