Abstract

Sound-evoked spikes in the auditory nerve can phase-lock with submillisecond precision for prolonged periods of time. However, the synaptic mechanisms that enable this accurate spike firing remain poorly understood. Using paired recordings from adult frog hair cells and their afferent fibers we show here that during sinewave stimuli EPSC failures occur even during strong stimuli. However, exclusion of EPSC failures leads to mean EPSC amplitudes that are independent of Ca2+ current. Given the intrinsic jitter in spike triggering, evoked EPSPs and spikes had surprisingly similar degrees of synchronization to a sinewave stimulus. This similarity was explained by an unexpected finding: large-amplitude multiquantal EPSCs have a significantly larger synchronization index than smaller evoked EPSCs. Large EPSPs therefore enhance the precision of spike timing. The hair cells’ unique capacity for continuous, large-amplitude, and highly synchronous multiquantal release thus underlies its ability to trigger phase-locked spikes in afferent fibers.

Keywords: auditory nerve, frog hair cells, phase-locking, paired recordings, sound frequency and intensity encoding, ribbon synapses, afferent fiber spikes

Introduction

The precision of synaptic transmission is intrinsically limited by the stochastic nature of synaptic vesicle release and an inherent jitter in the exact timing of evoked spikes. Nevertheless, the auditory system manages to attain extraordinary temporal precision. Localization of low-frequency sounds, for example, requires the preservation of temporal delays in the range of tens of microseconds, thus allowing the discrimination of sound sources only 2° apart (Carr and MacLeod, 2010; Köppl, 1997). Furthermore, this temporal accuracy occurs for both high and low intensity sounds. This is remarkable because synapses often experience vesicle pool depletion and/or asynchronous release during strong stimulation, which degrades spike reliability and timing precision, whereas low intensity stimulation leads to failure or delayed release, which will also degrade spike reliability and precision. What specialized mechanisms allow hair cell synapses to maintain both spike count reliability and precise timing during prolonged stimulation at different sound levels?

Hair cell synapses are characterized by a synaptic ribbon, the preferential site of vesicle exocytosis (Zenisek et al., 2003; Matthews and Fuchs, 2010; Safieddine et al., 2012). A hallmark of hair cell exocytosis is a prominent form of multivesicular release (Glowatzki and Fuchs, 2002; Keen and Hudspeth, 2012). This type of release is Ca2+-dependent at retinal ribbon-type synapses (Singer et al., 2004). However, EPSC amplitudes are Ca2+-independent at rat inner hair cell synapses (Goutman and Glowatzki, 2007). By contrast, EPSC amplitudes at frog and turtle auditory hair cell synapses are Ca2+-dependent (Li et al., 2009; Schnee et al., 2013). What are the origins for this difference and what is the physiological role of multivesicular release at hair cell synapses?

An important property of sound-evoked spikes, throughout the auditory system, is phase-locking. Hair cells faithfully follow sound wave sinusoidal cycles with their membrane potentials for low-frequency sounds (Crawford and Fettiplace, 1981; Palmer and Russell, 1986). Likewise, auditory nerve fibers tend to fire spikes at a particular time point (phase) of each sinusoidal cycle. This phenomenon of phase-locking thus starts at the first synapse of the auditory pathway. However, the underlying biophysical mechanisms that enhance phase-locking at adult hair cell synapses have not been fully identified, in part because of the fragile nature of the mammalian cochlea and the small size of its afferent fiber terminals.

Auditory nerve fiber recordings in amphibians, birds, and primates shows that at the nerves characteristic frequency the timing (or phase) of the spikes remains invariant as stimulus intensity increases (Rose et al., 1967; Hillery and Narins, 1984; Gleich and Narins, 1988). However, synaptic delays at conventional and ribbon-type synapses are reduced by fast and large [Ca2+]i rises (Heidelberger et al., 1994; Beutner et al., 2001; Schneggenburger and Neher, 2000). The timing of evoked spikes should thus undergo a phase change for progressively more intense sounds. What are the synaptic mechanisms that avoid phase advances at higher sound levels? A major hypothesis is that multivesicular release is Ca2+-independent at hair cell synapses (Fuchs, 2005; Goutman, 2012). However, this hypothesis has not been tested using physiologically relevant sinewave stimulation protocols in adult animals that can hear low frequency sounds.

Here we used paired recordings from bullfrog auditory hair cell synapses to study the biophysical mechanisms that promote phase-locking. Our in vitro recordings of EPSPs and spikes evoked by sinusoidal stimuli that mimic pure tone sounds recapitulated several key features of in vivo recordings of afferent fiber spikes. Counter-intuitively, we find that large multiquantal EPSC events are better phase-locked than small evoked EPSCs. Large multiquantal EPSPs, produced by the coincident release of more than 4–5 quanta, thus enhance the precision of spike timing. By filtering out small and less precisely timed EPSPs, the hair cell synapse promotes the precise phase-locking of afferent fiber spikes to incoming sound waves.

Results

Hair cell resonant frequencies

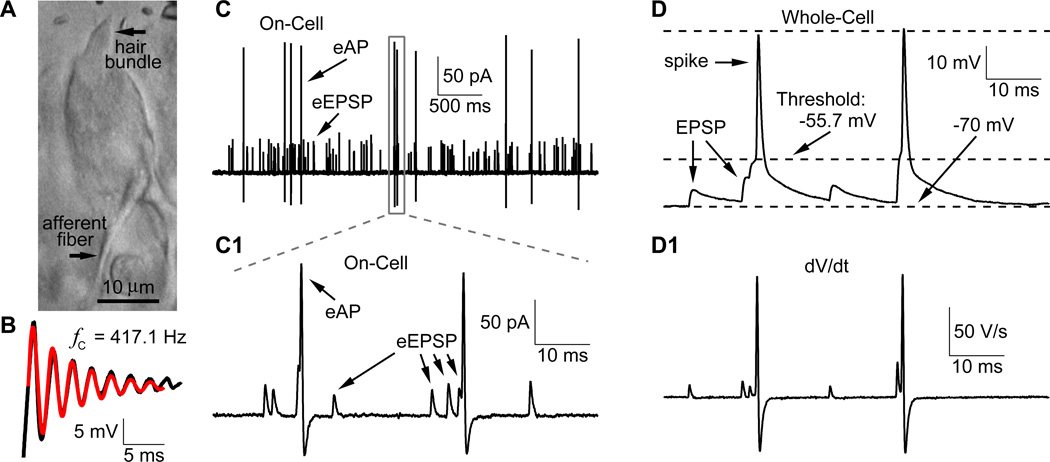

Hair cells are tightly imbedded in the epithelia of hearing organs. We obtained access to bullfrog amphibian papilla hair cells by cracking open the epithelium in the middle region (Figure 1A; Keen and Hudspeth, 2006). The amphibian papilla is organized tonotopically from its rostral to caudal end for acoustic stimuli that range in frequency from 100 to 1250 Hz (Lewis et al., 1982). Recordings from turtle and frog hair cells reveal that they are electrically tuned (Crawford and Fettiplace, 1980; Pitchford and Ashmore, 1987). To determine their characteristic frequency (fC), hair cells were kept under whole-cell current-clamp while current steps were injected. The voltage response was a damped oscillation that could be fit with a sinusoidal wave function whose amplitude decayed exponentially (Figure 1B; Catacuzzeno et al., 2003; see Experimental Procedures). For 11 hair cells, fC = 409 ± 28 Hz (at an average steady-state membrane potential of −48.7 ± 2.6 mV; quality factor, Q = 5.2 ± 1.3). Hair cells had a resting capacitance of 11.5 ± 1.4 pF and a length of 25 to 30 µm (Figure 1A; n=20). These properties are indeed typical of middle region hair cells (Smotherman and Narins, 1999). We are thus studying a fairly uniform distribution of hair cells specialized for detecting and transmitting sounds in the mid-frequency bandwidth.

Figure 1.

Hair cell ribbon synapses in bullfrog amphibian papilla. A) DIC image of the split-open semi-intact preparation in bullfrog amphibian papilla. The hair cell and its connected afferent fiber can be clearly identified based on their distinct morphology. B) The hair cell characteristic frequency (fC) was determined by injecting a current step to the hair cell under current-clamp. The voltage response (in black) was fit with a sine wave function whose amplitude decayed exponentially (red trace, fC = 417 Hz; see Experimental Procedures). C) A representative cell-attached, or on-cell, recording with GΩ seal of spontaneous extracellular EPSPs (eEPSPs) and extracellular action potential (eAPs) spikes from an afferent fiber. C1) Part of the recording in panel C (gray box in C) is shown with high temporal resolution. Note that the signal-to-noise ratio is sufficiently high so that individual eEPSPs and spikes (eAPs) can be identified. D) Spontaneous EPSPs and spikes under whole-cell current-clamp from a different afferent fiber, showing that spikes are triggered by either a large EPSP or the summation of a few closely timed EPSPs. D1) The first derivative (dV/dt) of the data in panel D reveals a trace resembling that of panel C1. This explains the origin of the shape of eEPSPs and eAPs waveforms.

Spontaneous eEPSPs and spikes: cell-attached and whole-cell recordings

Afferent fibers in the mid-frequency region of the amphibian papilla often form a claw-like terminal with a single hair cell (Lewis et al., 1982; Simmons et al., 1995; Keen and Hudspeth, 2006), that contacts ~30 synaptic ribbons (Graydon et al., 2011). To study the spike generation properties of the afferent fiber, we first made non-invasive cell-attached recordings with GΩ seals. In 45 of 58 afferent fibers, we observed spontaneous extracellular action potentials (eAP), which occurred either randomly (Figure 1C, n = 23) or in bursts (n = 22) with a frequency range of 0.05 to 20 Hz (average of 5.6 ± 5.8 Hz; n = 45). Our average in vitro spike rate is thus similar to the in vivo median spontaneous spike rate of 8.6 Hz for frog auditory nerve fibers (Christensen-Dalsgaard et al., 1998).

Some afferent fiber recordings also displayed copious spontaneous extracellular EPSPs (eEPSPs). In 11 fibers the signal-to-noise ratio was excellent, allowing us to clearly detect and analyze the individual eEPSPs (average eEPSP and spike frequency were 87.4 ± 76.4 Hz and 2.0 ± 2.3 Hz, respectively; Figure 1C1). Spikes were always triggered right after one large eEPSP, or after 2 to 3 closely timed eEPSPs, suggesting that they are all evoked by eEPSPs. However, spikes were much less frequent than eEPSPs, so the vast majority of eEPSPs failed to trigger spikes. Similar findings are reported for adult turtle and young rat afferent fibers (Yi et al., 2010; Schnee et al., 2013), but more mature rat fibers appear to spike for nearly every EPSP event (Geisler, 1997; Siegel, 1992; Rutherford et al., 2012).

To calculate the input resistance (Rinput) of the afferent fibers, we made whole-cell patch-clamp recordings with a potassium-based internal solution. We then injected negative step currents (50 to 250 pA) to the fiber under current-clamp and the steady-state voltages were measured for all steps and plotted against the current amplitude. From the slope of a linear fit to the data we obtained Rinput = 148 ± 64 MΩ (n=6). This relatively low input resistance of the afferent fiber explains in part why small amplitude EPSPs are unable to trigger spikes.

Under whole-cell current-clamp, we next studied the EPSPs and spikes. The resting membrane potential (Vrest) of the afferent fibers was −69.8 ± 0.7 mV (n=6; Figure 1D), a similar value to rat auditory afferents (Yi et al., 2010; Rutherford et al., 2012). The average EPSP frequency was 80.5 ± 55.8 Hz (n=7) and the spike frequency 7.4 ± 9.8 Hz (n=7), neither of which is significantly different from the value obtained from cell-attached recordings (p>0.05, unpaired Student’s t-test). The average spike amplitude and half-width was 60.4 ± 26.0 mV and 0.74 ± 0.18 ms, respectively (n=5). Note that the derivative of the whole-cell current-clamp data produced traces that were remarkably similar to those from cell-attached recordings (Figures 1D1 and 1C1). Indeed, cell-attached recordings measure a current proportional to cp•dV/dt, where cp is the membrane capacitance of the patch. Action potential spikes thus always have a biphasic waveform, with a prominent undershoot, whereas eEPSPs have a monophasic rise and decay with no undershoot (see Lorteije et al., 2009). So spikes and eEPSPs can be distinguished without any ambiguity. We conclude that spontaneous EPSPs occur frequently, although they trigger spikes only sparsely.

Quantal content of spike-triggering EPSCs

Figure 1D shows that spike threshold occurs at about −56 mV, suggesting that a depolarization ≥14 mV from Vrest is necessary to trigger a spike. When we depolarized afferent fibers with a 2 ms step current injection, we determined that the spiking threshold Vthreshold = −58.1 ± 4.6 mV (n=9). Thus, to trigger a spike, the amplitude of depolarization has to be ≥ 12 mV (Vthreshold − Vrest). Therefore, a current step with an amplitude ≥ 80 pA ([Vthreshold − Vrest]/Rinput) can trigger a spike. However, individual EPSCs are transient currents, with a 10 to 90% rise time of <0.25 ms and a decay time constant of ~0.5 ms (Li et al., 2009). Therefore, in order to generate the same depolarization the EPSC has to have considerably larger amplitude than our 2 ms step current (see Fig. S2).

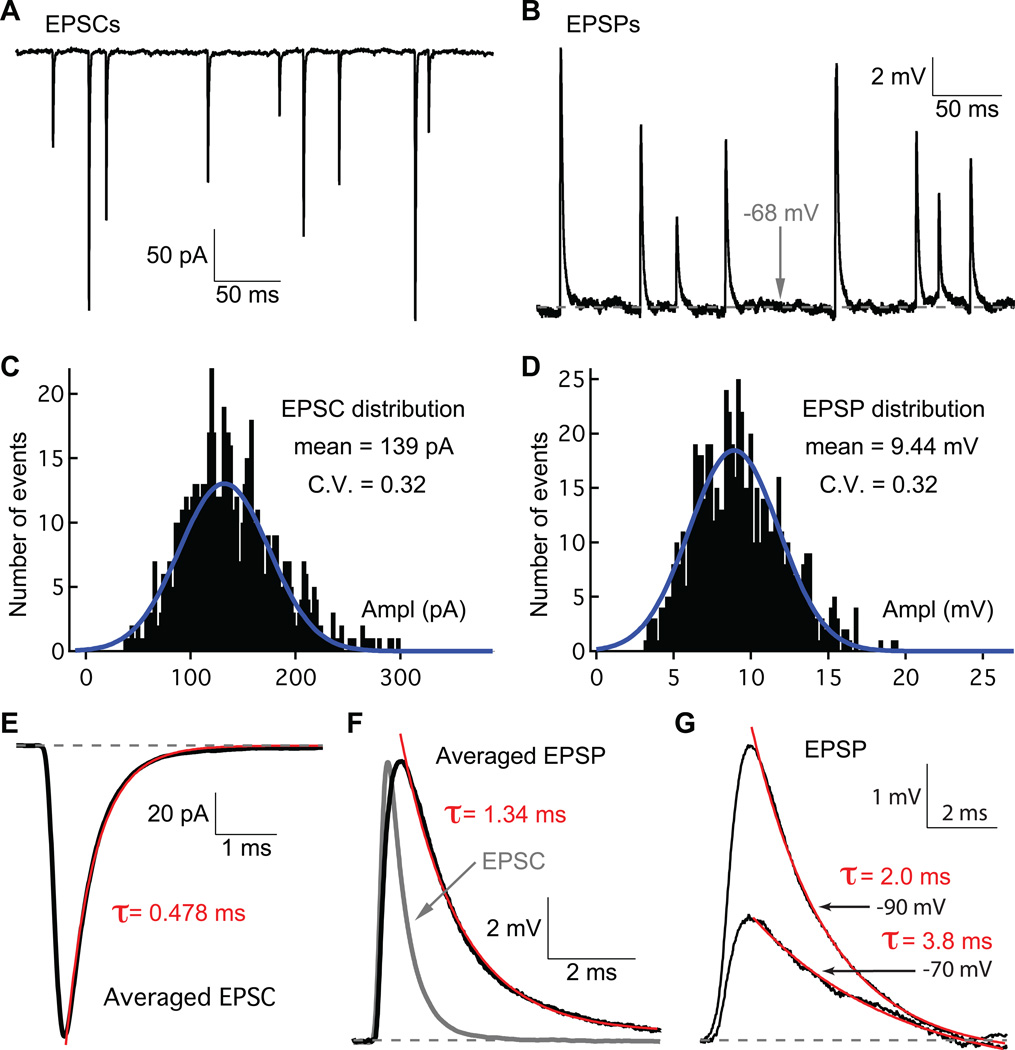

In order to determine how large the EPSC amplitude needs to be to trigger a spike, we recorded spontaneous EPSCs and EPSPs from the same afferent fiber (Figure 2A and 2B). Under voltage-clamp, with a holding potential of −90 mV, the amplitude distribution of EPSCs can be fit well by a Gaussian function with mean amplitude of 153 ± 35 pA (n=6; coefficient of variation = CV = 0.37 ± 0.07; Figure 2C; Li et al. 2009). With a resting membrane potential near −70 mV, recordings under current-clamp from the same afferent fibers reveal an EPSP amplitude distribution that can also be fit by a Gaussian function with mean amplitude of 8.3 ± 3.7 mV (n=6; CV= 0.38 ± 0.09; Figure 2D). From all 6 afferent fibers at the membrane potential of −70 mV, we determined the average impedance as the ratio (mean EPSP)/(mean EPSC) = 67.5 ± 22.5 MΩ. Therefore, in order to reach the threshold depolarization of ≥ 12 mV, the EPSC amplitude should be ≥ 180 pA (12 mV/67.5 MΩ), which corresponds to the release of around 4 to 5 vesicles (EPSC quantal size = 44 pA at −70 mV; Li et al., 2009). These results suggest that the afferent fiber acts as a low pass filter that eliminates high-frequency “noise” (small amplitude EPSCs that occur at high rates) in favor of low-frequency “signals” (large EPSCs that occur at lower rates and trigger spikes).

Figure 2.

Spontaneous EPSCs and EPSPs from a single afferent fiber. A and B) Example traces of EPSCs and EPSPs recorded from the same afferent fiber. In panel A the fiber was voltage-clamped at −90 mV, whereas in panel B current-clamp recordings had a resting potential to about −68 mV. C and D) Amplitude distributions of the EPSCs and EPSPs from the same afferent fiber as in panel A and B. Both distributions can be fit with a Gaussian function (C.V. = coefficient of variation). E and F) The average EPSC and EPSP kinetics at the mean peak values are shown, respectively. The average EPSC was inverted (gray) and superimposed with the average EPSP in panel F to show that both the rise and decay of the EPSP are slower than the EPSC. G) EPSPs recorded from an afferent fiber at two different resting membrane potentials. The EPSP decay time constant was on average smaller at a resting potential of −90 mV than for −70 mV. In panels E, F, and G single exponential fits (red) and decay time constants are shown. In all the panels the bath solution contained 1 µM TTX.

Because EPSPs can summate to trigger a spike we determined their kinetics. The EPSP time course was slower than that of the EPSC (Figure 2E and F). For 8 afferent fibers we determined the 10% to 90% rise time of spontaneous EPSPs to be 0.66 ± 0.23 ms and the single exponential decay time constant to be 3.2 ± 0.5 ms at −70 mV and 1.98 ± 0.21 ms at −90 mV (p<0.05). This EPSP kinetics is about 2-fold faster than results obtained from young rat afferent fibers at room temperature (Yi et al., 2010; see, however, Grant et al., 2010).

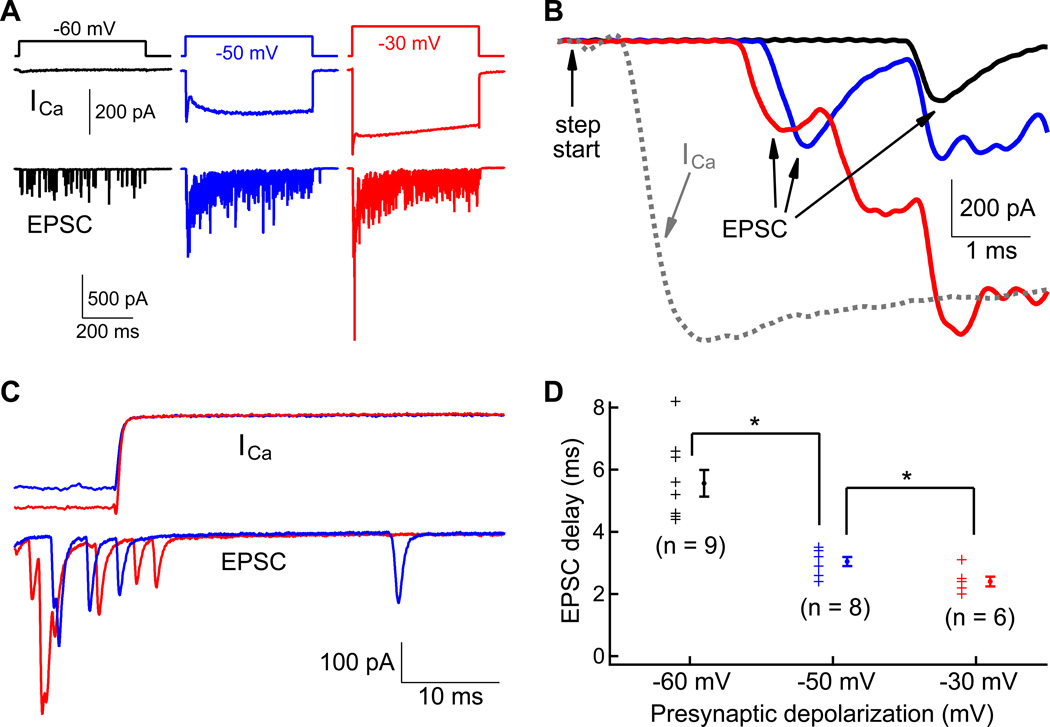

Synaptic delays and asynchronous release

To investigate how presynaptic depolarizations of variable strength affect EPSC delays we recorded EPSCs evoked by voltage-clamp step depolarizations of the hair cell to different voltages. We then measured the delay from the start of the step depolarization to the peak of first EPSC (Figure 3A and 3B). For depolarizations to −60, −50 and −30 mV, this delay was 5.6 ± 1.3 ms (n=9), 3.1 ± 0.4 ms (n=8) and 2.4 ± 0.4 ms (n=6), respectively (Figure 3D). A one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis shows that the synaptic delay was significantly shortened for stronger depolarization (p<0.05). These EPSC delays are significantly shorter than those of rat auditory and vestibular hair cell synapses (Goutman and Glowatzki, 2007; Songer and Eatock, 2013). However, synaptic delays become shorter for more depolarized holding potentials (Goutman, 2012). Like other conventional and ribbon-type synapses, we thus conclude that stronger presynaptic depolarizations lead to shorter synaptic delays at bullfrog hair cell synapses.

Figure 3.

The Ca2+-dependent synaptic delay of evoked EPSCs. A) Ca2+ currents (ICa) and EPSCs (lower panel) are shown from a hair-cell and afferent fiber paired recording. The hair cell was stepped to −60 mV (black), −50 mV (blue) and −30 mV (red). This generated progressively larger amplitude ICa and EPSCs. B) The onset of the three EPSC responses of panel A are superimposed and plotted at higher temporal resolution. The dashed line shows the Ca2+ current in response to the −30 mV step depolarization. Note how the delay of the EPSC becomes shorter with stronger depolarization. C) Ca2+ currents and evoked EPSCs at the offset of the step depolarizations (same data as panel A). Note that there was very little asynchronous release at both step depolarizations to −50 mV and −30 mV. D) The EPSC delays were measured from the start of the step depolarization to the peak of the first EPSC. At each potential, individual data points are shown in the left and the averaged date are shown on the right. The EPSC delay becomes progressively shorter with stronger depolarizations.

After the end of the depolarizing step the Ca2+ current deactivated quickly and little asynchronous release was observed (Figure 3C). The release machinery is thus able to follow sharp fluctuations in the hair cell’s membrane potential. We also measured the latency from the start of a depolarizing step to the peak of the first action potential spike. When we stepped hair cells from −90 mV to −50 mV, the average delay of the first spike was large and variable (41.5 ± 48.7 ms; n=8). For a stronger step depolarization to −30 mV, the delay decreased significantly to only 3.81 ± 1.82 ms (n=15; p<0.01, unpaired Student's t-test; data not shown). Accordingly, the first spike latency to a “click” sound of 400 Hz varies from 3 to 7 ms in frog auditory nerve, and it decreases with louder click stimuli (Hillery and Narins, 1987). The first spike latency of the afferent fiber thus carries information about the onset timing and strength of the presynaptic hair cell depolarization (Wittig and Parsons, 2008; Buran et al., 2010).

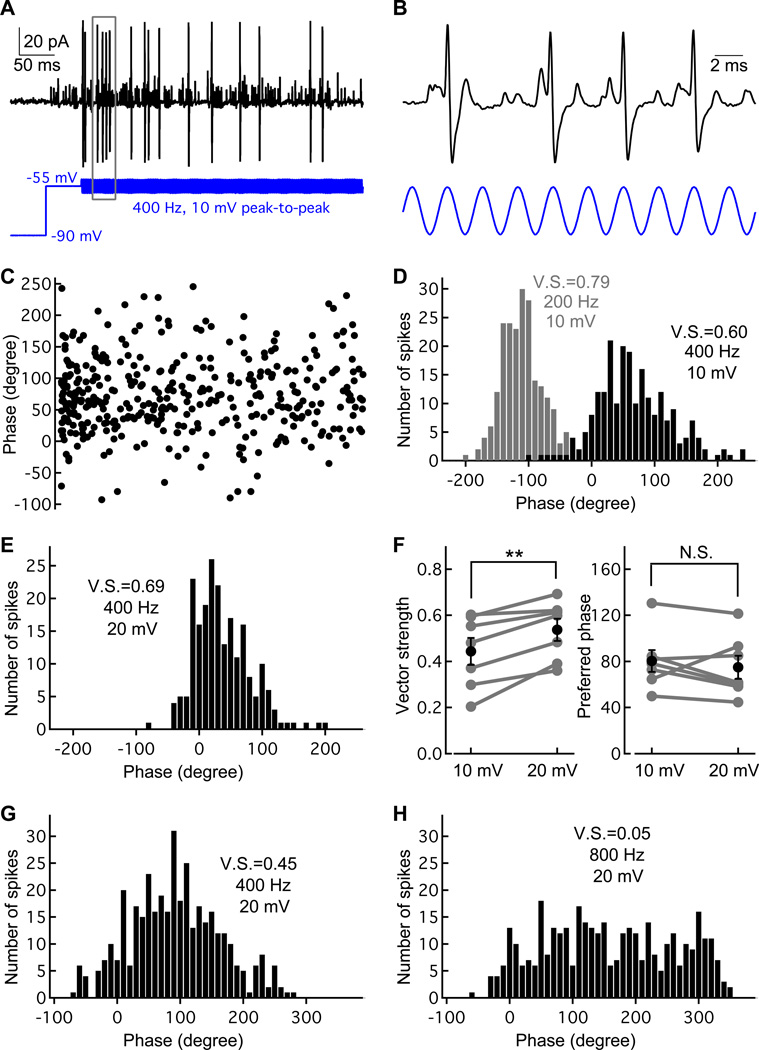

Phase-locking of spikes at in vitro hair cell synapses

Given that synaptic delays vary for different levels of presynaptic depolarization, how is spike phase invariance established for sounds of different intensities? To explore this question, we stimulated hair cells with sinusoidal voltage commands similar to those that hair cells experience in vivo (Russell and Sellick, 1983). Auditory hair cells have an in vivo resting membrane potential of about −55 mV, and their voltage responses to a pure tone sound follow a sinusoid with amplitudes of up to 20 mV peak-to-peak (Crawford and Fettiplace, 1980; Corey and Hudspeth, 1983; Holt and Eatock, 1995). Therefore, we used sinusoidal voltage commands centered at −55 mV with peak-to-peak amplitude up to 20 mV. Figure 4A shows the stimulus template: we first stepped the hair cell potential from −90 mV to −55 mV for 50 ms and then a sinusoidal wave was applied. This sinusoidal wave had a frequency of 400 Hz, a 10 mV peak-to-peak amplitude, and a total length of 4.8 s (1,920 cycles). This stimulus was repeated several times during the hair cell recording until enough spikes (> 200) were generated for analysis. The response (black trace) contained both eEPSPs and spikes. Part of the traces in A are shown in Figure 4B with higher temporal resolution. Note how every spike peak occurs at nearly the same time point (phase) of the sinusoidal cycles. The spikes are clearly phase-locked to the sine wave stimulus.

Figure 4.

Phase-locking at hair cell ribbon synapses in vitro. A) An example of cell-attached recording (black) from an afferent fiber while a sinusoidal voltage command (blue; 400 Hz) was applied to the connected hair cell under voltage-clamp. The sinusoidal wave had a peak-to-peak amplitude of 10 mV centered at −55 mV. Each stimulus lasted 5 s and was repeated as necessary to obtain a sufficient number of spikes for analysis. Note that there are more spikes in the beginning of the sine wave stimulus than in the end, which leads of spike rate adaptation as seen in vivo. B) Part of the record in A (within the gray box) is shown here at higher temporal resolution. Note that all four spikes occur after a preceding eEPSP and the spike peaks all coincide with the same cycle of the sinewave. The spikes are thus all phase-locked. C) For each spike, the time of the positive peak was detected and converted to phase (0° to 360°) according to the stimulus voltage-clamp template. D) A histogram was built from the data in C with a bin size of 10° (black bars). Another histogram from the same recording was built for a sine wave stimuli of 200 Hz and same amplitude (gray bars). For the 200 Hz stimuli, a phase shift to the left occurred and the vector strength (V.S.) increased (see also Figure S4). In vivo recordings report similar results for pure tone sound stimuli. E) Period histograms for stimuli with an amplitude of 20 mV at 400 Hz, from the same pair as in panel D. F) Pooled data from 7 pairs showing vector strength was significantly increased when stimuli amplitude doubled, whereas the average phase remained unchanged. G and H) Period histograms from a different paired recording show good phase-locking at 400 Hz but not at 800 Hz.

To quantify the precision of spike timing we detected the time of each spike peak and the corresponding phase in the sinusoidal voltage command. Note that most of the data points occur between 0° and 100° (Figure 4C). In order to build a period histogram, we ran a procedure to unwrap the phases in a data set: a phase will be corrected by adding or subtracting 360° if doing so can reduce the variation of phases in that data set (Paolini et al, 2001). From these unwrapped phases we built a histogram using a bin size of 10° (Figure 4D). This process does not change the synchronization index of the data set, but it is necessary for building a histogram with a single peak that lies between 0° and 360°.

To quantify the precision of phase-locking we calculated the vector strength (V.S.) or synchronization index. Vector strength (V.S.) varies from 0 (no synchronization) to 1 (perfect synchronization; see Experimental Procedures). For sinusoidal waves with the same amplitude but different frequencies, the V.S. of the spikes deteriorated as the frequency increased beyond the characteristic frequency (Figure 4G and 4H: V.S. = 0.45 for 400 Hz and V.S. = 0.05 for 800 Hz). However, phase-locking improved as the frequency decreased (Figure 4D: V.S. = 0.60 for 400 Hz and V.S. = 0.79 for 200 Hz).

Note also the leftward shift of the average phase for a frequency of 200 Hz. This leftward phase shift also occurs in vivo at frog afferent fibers stimulated by sound, where V.S. = 0.6–0.7 for 400 Hz pure tones and V.S. = 0.8–0.9 for 200 Hz pure tones (Hillery and Narins, 1987; see also Fig. S4). However, for sinusoidal waves at a fixed frequency (fC = 400 Hz) but with different amplitudes (10 mV vs. 20 mV), the averaged phase remained the same (80.3 ± 25.0° for 10 mV, 74.9 ± 26.4° for 20 mV, n=7; p>0.05, paired Student’s t-test), although the phase-locking improved significantly with stronger depolarization (V.S. = 0.44 ± 0.16 for 10 mV, V.S. = 0.54 ± 0.13 for 20 mV, n=7; p<0.01, paired Student’s t-test). Again, these results mimic closely in vivo fiber recordings with sound stimulation at different intensities (Hillery and Narins, 1984). Our in vitro hair cell synapse recordings with sine wave stimulation thus reproduce extremely well several results obtained from in vivo frog afferent fibers with acoustic stimulation.

Phase-locking of EPSCs

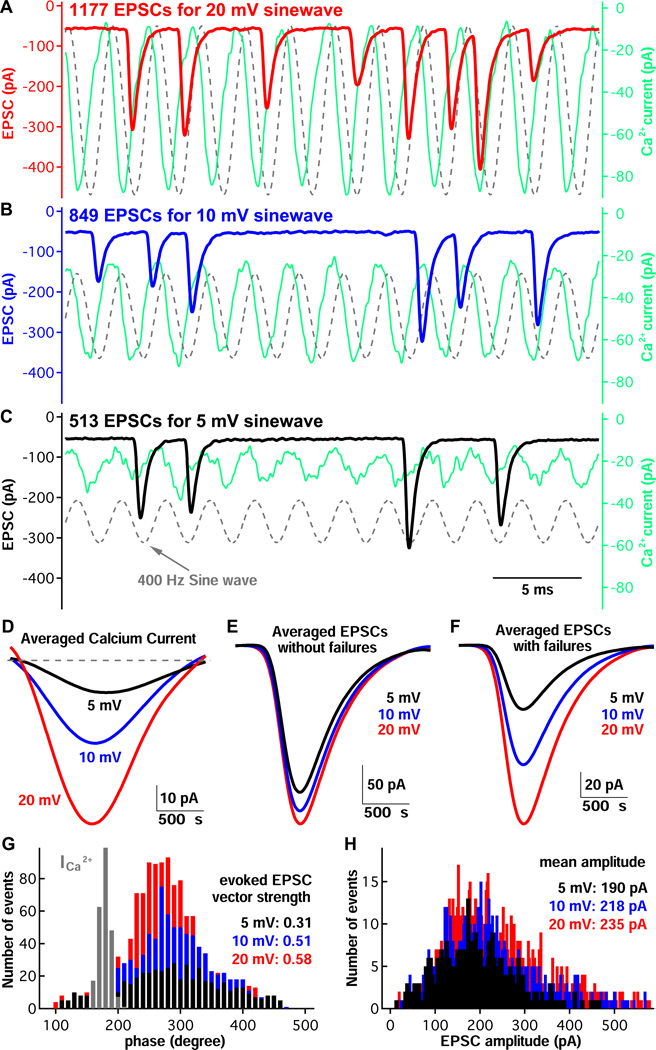

We next recorded EPSCs from afferent fibers under voltage-clamp at −90 mV while applying sinusoidal (400 Hz) stimulations to connected hair cells (Fig. 5 and S1). The V.S. of the EPSC varied from 0.5 to 0.7, and like the V.S. for spikes (Figure 4D), the EPSC V.S. increased as the stimulation frequency decreased (see Fig. S4). As expected, a partial block of hair cell Ca2+ current with Cd2+ significantly reduced EPSC amplitudes and V.S. (Fig. S3). We also calculated the temporal dispersion of the EPSC, a measure of event jitter within a cycle (Köppl, 1997; Paolini et al., 2001). This parameter decreased significantly as the frequency increased. Interestingly, at fC = 400 Hz the temporal dispersion was low (about 380 µs) while the vector strength was still relatively high (about 0.5; Fig. S5). As shown in Figure 5A, B and C, Ca2+ current (green traces) followed faithfully on a cycle-by-cycle basis the voltage stimulus. To quantify how well Ca2+ currents followed stimulation cycles, we detected the peak time of the Ca2+ currents for all cycles and then calculated V.S., which was 0.90 ± 0.06, 0.96 ± 0.04 and 0.98 ± 0.02 (n=5; p<0.05 one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis) for stimulations at 5 mV, 10 mV and 20 mV, respectively. Ca2+ currents were thus highly phase-locked to sinusoidal stimulation and the degree of phase-locking improved significantly as stimulation became stronger.

Figure 5.

Phase-locking of EPSCs at hair cell ribbon synapses. A) Presynaptic Ca2+ current (in green) and postsynaptic EPSC (in red) from a hair cell-afferent fiber pair in response to a sinusoidal voltage-clamp stimulus applied to the hair cell. The stimulus had a peak-to-peak amplitude of 20 mV centered at −55 mV (in dashed gray). B and C) EPSC responses to a 10 mV (B; blue trace) and 5 mV (C; black trace) sinusoidal stimuli from the same pair as in panel A. Note that the number of EPSCs decreases as the sinusoidal wave amplitude decreases. D, E and F) Average Ca2+ currents (D), average EPSCs without failures (E), and average EPSCs with failures included in the average (F) were obtained from the same paired recording as in panels A (in red), B (in blue) and C (in black). G) The time of each EPSC peak was converted to phase (in degree) according to the stimulus sinewave templates, and the histogram of these phases for each stimulation condition is shown. The distribution of peak Ca2+ current phases was scaled and shown in gray (it had a peak of 800 events before scaling). Note that increasing stimulus amplitude increases vector strength, whereas the average phase remains nearly unchanged. H) EPSC amplitude distributions at three different stimulus levels. The mean EPSC amplitude, as shown in panel E, remains nearly unchanged at a value of about 200 pA.

Although Ca2+ currents occurred faithfully at every cycle of the sine wave, EPSCs did not occur at every cycle. For weak stimuli of 5 mV, EPSCs had a low success rate that varied from 4% to 30% among different afferent fibers with an average of 14.7±9.3% (n=5). For stronger stimuli of 10 mV, the success rate was increased to 21.8±14.5%, and it was further increased to 35.4±21.5% for stimuli at 20 mV (n=5, p< 0.05 one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis). However, even for a weak stimulus of 5 mV, the EPSC was phase locked to the stimulating template with a vector strength V.S. = 0.28 ± 0.09 (n=5). EPSC phase-locking improved significantly for stronger stimulation: V.S. = 0.48 ± 0.11 at 10 mV and V.S. = 0.61 ± 0.11 at 20 mV (n=5, p<0.01 one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis).

Remarkably, the average EPSC amplitude did not change significantly for stimuli of different amplitudes (185 ± 48 pA for 5 mV; 199 ± 58 pA for 10 mV; 194 ± 56 pA for 20 mV, n=5, p>0.05 one-way ANOVA; Figure 5E and 5H). Likewise, the average preferred phase of the EPSCs did not change as the strength of the stimulus was increased (Figure 5G). Indeed, the average EPSC phase for 5 mV, 10 mV and 20 mV stimulus sine waves of 400 Hz are not significantly different (respectively, 323 ± 23 degrees, 320 ± 23 degrees, 320 ± 29 degrees; n=5 paired recordings; p>0.05 one-way ANOVA).

During prolonged sinewave stimulation the frequency of EPSC events depended on stimulus strength (or Ca2+ current amplitude), but the average amplitude of the EPSCs, calculated without including EPSC failures remains effectively Ca2+ current independent (Figure 5E and 5H). However, the average evoked EPSC amplitude was a linear function of the Ca2+ current amplitude when the EPSC average included also the EPSC failures (Figure 5D and 5F; R2 = 0.95 ± 0.06; slope = 0.91 ± 0.73; n=5). This agrees with previous results showing a linear synaptic transfer function at this frog synapse with step depolarizations (Keen and Hudspeth, 2006; Cho et al., 2011), and at mammalian auditory and vestibular hair cell synapses (Dulon et al, 2009; Johnson et al., 2008, 2010).

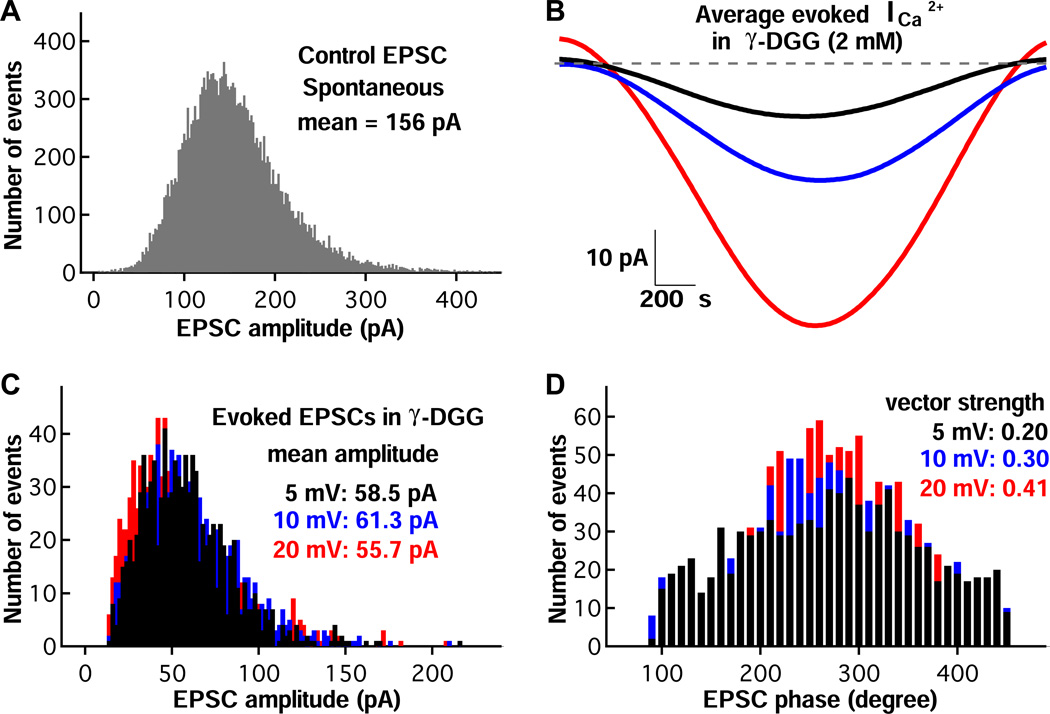

One explanation for the invariance of the EPSC amplitude with stimulus strength is that postsynaptic AMPA receptors are saturated. However, stronger stimuli failed to evoke a larger average EPSC when we repeated the same experimental protocol of Figure 5 in the presence of the low affinity AMPA receptor antagonist γ-DGG (2 mM), which will protect receptors from saturation (Figure 6). Indeed, note that γ-DGG reduced significantly the amplitude of the evoked EPSCs (Figure 6C) compared to the spontaneous EPSCs that occur before the hair cell is voltage clamped (Figure 6A). Nevertheless, the average EPSC phase remained invariant to stimulus strength, although vector strength progressively increased with stimulus strength (Figure 6D). Similar results were obtained for six paired recordings in 2 mM γ-DGG. The average evoked EPSC amplitude invariance to stimulus strength is thus not due to AMPA receptor saturation. Postsynaptic specializations that aid the rapid diffusion of glutamate out of the synaptic cleft probably help this synapse to avoid AMPA receptor saturation and prolonged desensitization (Graydon et al., 2014).

Figure 6.

Phase-locking of EPSCs in γ-DGG, a rapidly dissociating and low-affinity AMPA receptor antagonist. A) EPSC amplitude distributions of spontaneous EPSCs in control solution. B) Using an identical voltage-clamp protocol as used in Figure 5, the average Ca2+ currents on hair cells evoked by sinusoidal voltage commands at 20 mV (red), 10 mV (blue) and 5 mV (black) in the presence of 2 mM γ-DGG is shown. C) For the same afferent fiber as in panel A, the amplitude distributions of evoked EPSCs are similar for the different amplitudes of the hair-cell sinewave stimulus in the presence of 2 mM γ-DGG. Note that the mean EPSC amplitude is now about one-third of that shown for panel A, and this mean remains nearly unchanged at a value of about 60 pA. D) Distributions of evoked EPSC phases for the three different hair-cell sinewave stimuli. Note that the vector strength increases with stronger stimulus, whereas the average phase angle remains unchanged.

Spike timing precision: Large EPSCs have higher vector strength

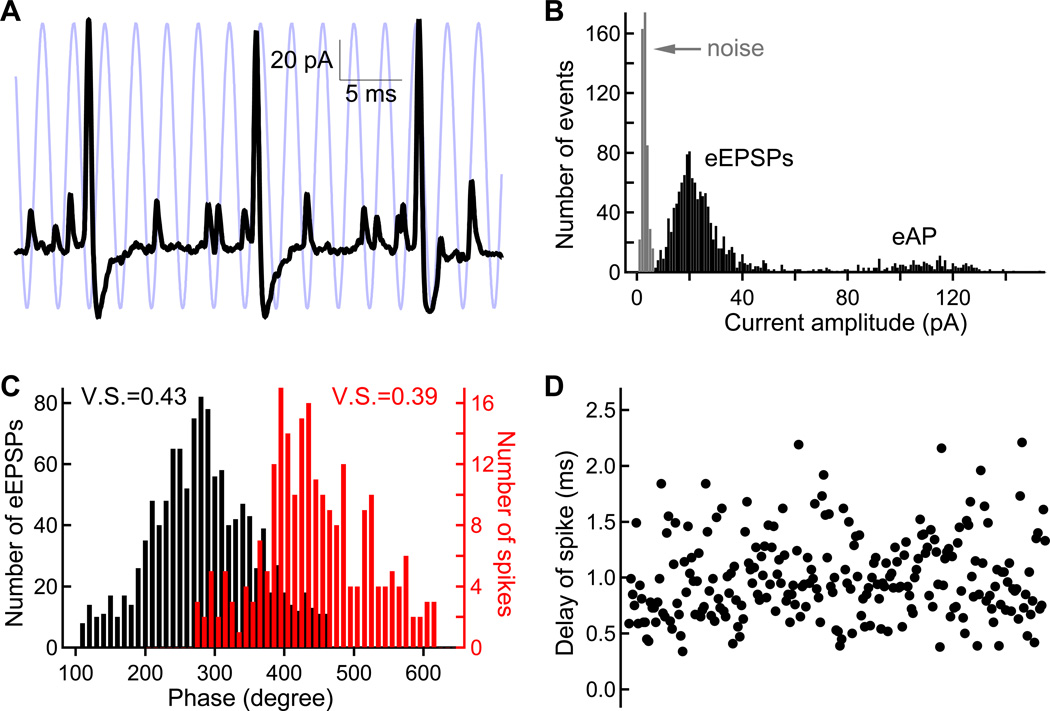

The spike generating mechanism of the afferent is subject to an intrinsic “jitter” and to a refractory period (see Fig. S2), so one expects some significant degradation of phase-locking quality in the step from EPSC to spike triggering. However, to our surprise, for a 20 mV sinusoidal wave stimulus, the spike vector strength (V.S. = 0.54 ± 0.13, n=7) is only slightly lower than that of EPSC vector strength (V.S. = 0.61 ± 0.11, n=5) and this difference is not significant (p>0.05 for unpaired Student’s t-test). To further confirm this finding, we took advantage of cell-attached (or on-cell) recordings with high signal-to-noise ratio (see Figure 1C). In this recording mode, one can reliably detect eEPSPs and spikes from the same afferent fiber (Figure 7A and 7B). This allowed us to compare phase-locking of eEPSPs and spikes from the same recording. For 3 paired recordings with very low noise in the afferent fiber on-cell recording, we confirmed that the spike vector strength is only slightly lower than that of the eEPSPs (Figure 7C). This seems to suggest that the spike generating mechanism of the afferent fibers is nearly as precise as the EPSP generating process, although spikes are triggered much more sparsely than EPSPs.

Figure 7.

Phase-locking of extracellular EPSPs (eEPSPs) and spikes. A) eEPSP and spikes were recorded in the cell-attached mode from an afferent fiber while the connected hair cell was stimulated with a sinusoidal voltage command (20 mV peak-to-peak centered at −55 mV, 400 Hz, light blue trace). B) The amplitude distribution of eEPSPs in panel A shows that the signal-to-noise ratio is excellent for distinguishing eEPSPs from noise and from the extracellular action potential (eAP). C) Histograms of eEPSP phases (black) and spike phases (red). The vector strength (V.S.) of spikes is only slightly smaller than that of eEPSPs. D) The delay from a spike peak to the closest eEPSPs that precedes that spike varies considerably from 0.4 to 2.5 ms. Given this wide variability in spike timing, the small difference in vector strength of panel C is quite unexpected.

To study the precision of the spike generator, we calculated the delay between the spike peak and the closest eEPSP peak, which identifies the eEPSP that triggered the spike. Note from Figure 4B and 7A that this delay can be clearly determined in low noise cell-attached recordings. The delay was surprisingly variable and ranged from a minimum of 0.4 ms to as long as 2.2 ms (Figure 7D). Therefore, as expected, the spike generating mechanism of the afferent fiber is not unusually precise, since spikes can be triggered over a long temporal window after an EPSP. Moreover, the precision of afferent fiber spiking is also limited by the refractory period during repetitive stimulation, as well as fluctuations in resting membrane potentials that will produce an intrinsic “jitter” in spike timing (Fig. S2), all factors that will tend to degrade spiking precision relative to the timing of EPSC or EPSP events.

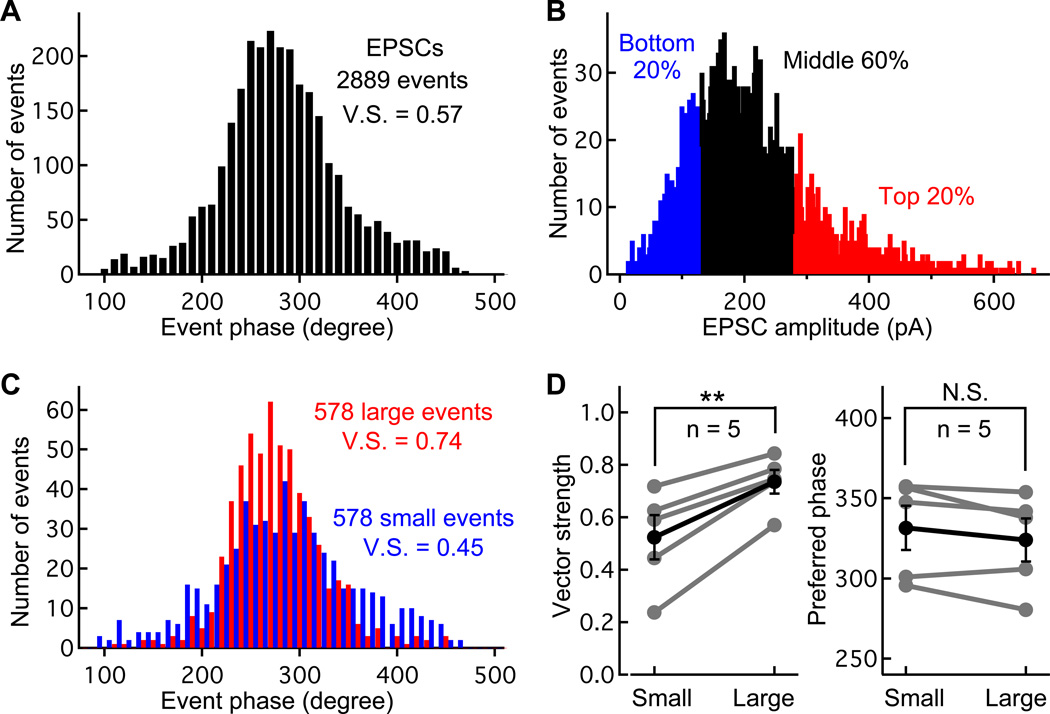

In order to overcome this inherent variability in the timing of spike generation, we postulated that large EPSPs, with amplitudes sufficient to quickly and reliably trigger spikes, must somehow be better phase-locked than smaller amplitude EPSPs. If this were the case, it could explain the results of Figure 7C. However, this is a counter-intuitive hypothesis because large EPSPs presumably require the opening of several Ca2+ channels to trigger the simultaneous release of several docked vesicles. Since Ca2+ channels open stochastically this should introduce some further temporal jitter in the overall exocytosis process when compared to small EPSPs, which require only the release of one or two quanta.

To test this hypothesis we analyzed a large data set of sinewave evoked EPSCs (2889 events; Figure 8A). Using EPSCs generated by the same sine wave stimulus, we selected a 20% sub-group of EPSCs whose amplitudes are larger than the rest of the EPSCs. We next selected a 20% sub-group of the EPSCs whose amplitudes are smaller than the rest of the EPSCs (Figure 8B and 8C). The top 20% of the events had an average amplitude of 381 pA (quantal content of about 5 or 6 vesicles; n=578 events), while the bottom 20% had an average amplitude of 93.4 pA (quantal content of about 1 or 2 vesicles; n=578 events). The top 20% EPSC sub-group had a significantly better vector strength (V.S. = 0.74) than the bottom 20% (V.S. = 0.45; Figure 8C). For six paired recordings, when we compared the phase-locking between the two sub-groups from the same fiber recording, we found that the top 20% EPSCs are significantly better phase-locked than the bottom 20% (Figure 8D; paired Student t-test, p<0.01).

Figure 8.

Large EPSCs are better phase-locked than small EPSCs. A) Period histogram of 2,889 EPSC phases obtained from an afferent fiber while the connected hair cell was stimulated with a sinusoidal voltage command (400 Hz, 20 mV peak-to-peak; V.S. = vector strength). B) The EPSC amplitude histogram of the 2,889 events in panel A. The EPSCs were sorted according to their amplitudes and the top 20% are shown in red and the bottom 20% in blue (578 events in each case). C) Histograms for the two 20% subgroups of EPSCs were plotted (top 20% in red, bottom 20% in blue). Note that the top 20% group has a higher vector strength than the bottom 20%. D) Pooled data from 5 afferent fibers showing that the V.S. of large EPSCs (top 20%) is significantly higher than that of small EPSCs (bottom 20%; paired Student t-test, p<0.01), whereas the preferred phase of the two sub-groups was not significantly different.

What is the contribution of spontaneous mEPSCs to the V.S. of small events? To address this we first note that mEPSCs occur at a low rate (~1 Hz; Li et al 2009). Assuming mEPSCs are Ca2+-independent and occur at 1 Hz, there are probably 5 mEPSCs in our 5 second sinewave stimuli. To correct for this “error” we randomly generated a phase number, compared this to the phases of the bottom 20% events, and then excluded the phase whose value was closest to the randomly generated one. We repeated this 5 times and re-calculated the V.S. to be 0.55 ± 0.20 (n=5; uncorrected: V.S. = 0.52 ± 0.19). Using this corrected value the top 20% events are still better phase-locked (n=5, paired Student t-test, p<0.05). We next used the fact that mEPSC amplitudes are <100 pA (Li et al 2009), and instead of using the bottom 20% events we used the middle 40% to 60% events. These events are >100 pA, so it is unlikely they contain spontaneous mEPSCs. Compared to these middle 20% events the top 20% are still better phase-locked (V.S. = 0.64 ± 0.12 vs. 0.74 ± 0.10, n=5, paired Student t-test, p<0.05).

Discussion

We have found that evoked EPSPs and spikes from the same afferent fiber have similar vector strength. Given the intrinsic jitteriness of spike generating apparatus in afferent fibers we expected lower vector strength for spikes compared to EPSPs. However, our results also show that large EPSCs are intrinsically better phase-locked than small amplitude EPSCs. Moreover, large and fast EPSPs will also trigger spikes more precisely. We thus propose that large EPSC events allow better temporal precision in spike triggering and compensate for the intrinsic variability of the spike generating mechanism. Our findings thus suggest a major and unexpected functional benefit of large EPSCs for hair cell synapses: enhancement of spike phase-locking to incoming sound waves.

Afferent fiber EPSPs and action potentials

Afferent fiber spikes had relatively small amplitudes of about 60 mV (Figure 1D; see also Yi et al., 2010; Schnee et al., 2013). This may be due to the distal location of the spike-generating zone (the locus of high Na+ channel density along the axon; Rutherford et al., 2012). Small spike amplitudes also occur in cochlear nucleus octopus cells and in auditory brainstem MSO neurons, which have distal spike triggering zones and large K+ currents (Scott et al., 2007; Oertel et al., 2009). These neurons function as coincidence detectors and require rapid rates of depolarization to fire spikes. Likewise, we find that frog auditory nerve fibers require fast rising and large amplitude EPSPs to fire spikes with reduced jitter (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2). However, closely timed EPSPs can summate and this can contribute to the generation of spikes (Figure 1D; Schnee et al., 2013).

In vitro sine-wave stimulation mimics in vivo sound-wave stimulation

We have found that non-invasive cell-attached recordings of extracellular action potentials and EPSPs are possible from the bullfrog afferent fibers (Figure 1C). Moreover, these extracellular spikes can be elicited in a phase-locked manner by hair-cell sine wave stimuli that mimic pure sound tones (Figure 4B). The resulting spike phase distribution is approximately Gaussian and the peak of the phase distribution shifts to the left for a lower frequency sine wave of 200 Hz (Figure 4D). Furthermore, the vector strength increases for the lower frequency sine wave stimuli (Figure 4D). Remarkably, in vivo recordings of frog auditory nerve spikes evoked by pure tone sounds show the same behavior suggesting that we were able to capture several of the key features of sound-evoked afferent fiber spiking with our in vitro recordings (Hillery and Narins, 1984, 1987).

Ca2+ currents, synaptic delays and asynchronous release

Hair cells can sustain high rates of release during strong step-like depolarizing pulses, whereas weaker step depolarizations produce smaller and less frequent EPSCs (Figure 3). The rates of vesicle release are clearly Ca2+ dependent (Neher and Sakaba, 2008; Schnee et al. 2005). The EPSC evoked by a −30 mV step had a short synaptic delay and was composed of distinct multiquantal events (Figure 3B). These distinct EPSC events may originate from different synaptic ribbons with heterogeneous release probabilities due to different densities of Ca2+ channels and docked vesicles (Frank et al., 2010; Liberman et al., 2011). In contrast to retinal ribbon synapses (Singer et al., 2004), we observed very little asynchronous release after hair cell hyperpolarization (Figure 3C and Fig. S1). The synapse is thus well tuned to register the sharp onset and offset of a sound stimulus (Christensen-Dalsgaard et al., 1998).

Like other conventional and ribbon-type synapses, EPSC delays become shorter with stronger step depolarization (Figure 3D; see von Gersdorff et al., 1998). One would thus have expected a phase advance with an increase in stimulus strength (Fuchs, 2005). When we use sine wave stimuli and include EPSC failures, the average EPSC amplitude depends linearly on Ca2+ current (Figure 5D and 5F), but exclusion of EPSC failures leads to Ca2+ current independent EPSCs and the EPSC phase becomes intensity invariant (Figure 5G). However, when we use sine wave stimuli of different frequencies, but fixed amplitude, the low frequency stimulus produces shorter synaptic delays than high frequency stimuli (Figure S4) and a spike phase advance (Figure 4D). Interestingly, sacculus bullfrog hair cells are tuned to release more efficiently with weak stimuli at their characteristic frequencies and this form of evoked exocytosis also appears to be Ca2+-current independent (Rutherford and Roberts, 2006) and is present in the amphibian papilla (Patel et al., 2012).

The data in Figure 5G allows us to calculate the average synaptic delay between the peak Ca current and peak EPSC evoked by the 400 Hz sine wave stimulus by simply converting the average Ca current phase (183 degrees) and average EPSC phase (281 degrees) into time and calculating their difference which is 0.68 ms. This value is similar to the synaptic delay of 0.7–0.8 ms measured from in vivo guinea pig inner hair cell synapses (Palmer and Russell, 1986). Note that this average synaptic delay does not depend on the amplitude of the sine wave, a necessary consequence of the EPSC phase invariance to stimulus intensity.

EPSC phase invariance to sine wave amplitudes

Intensity-independent phase locking of sound evoked spikes appears to be a general feature of frog (Hillery and Narins, 1984), songbird (Gleich and Narins, 1988), emu (Manley et al., 1997), and primate auditory nerves (Rose et al., 1967). Similar observations for sound levels from 20 to 80 dB are found also in the auditory nerve of cat (Liberman and Kiang, 1984), guinea pig (stimulation at “null” frequency; Palmer and Shackleton, 2008), and barn owl (Köppl, 1997). Phase angles of EPSPs are also intensity independent in the teleost Mauthner cell system during the auditory mediated escape behavior (Weiss et al., 2009). Our results also suggest that sound intensity is encoded by EPSC rates, whereas sound frequency can be encoded in an intensity-independent manner by the timing (or phase) of the EPSCs. In addition, note that vector strength increases with stimulus strength (Figure 5G), so changes in the precision of phase locking can also encode sound levels (Anderson et al. 1971; Avissar et al. 2007). The loudness and pitch of a low-frequency sound signal can thus be encoded in a single auditory nerve fiber via the rate and exact timing of spikes.

We found that even for very weak sine wave stimuli (5 mV peak-to-peak) the individual evoked EPSCs had large amplitudes, although the Ca2+ currents were small (< 20 pA; Figure 5C) and likely due to the opening of only a few Ca2+ channels (Kim et al., 2013). In fact, if we exclude failures, the average EPSC amplitude had very similar values for the different sinewave amplitudes (Figure 5E and 5H). This suggests that EPSCs amplitudes become effectively independent of Ca2+ current amplitude when hair cells are held at their physiological resting membrane potential and stimulated with sine waves. This provides support for previous proposals on the mechanisms for phase-invariance at different sound intensities (Fuchs, 2005; Goutman, 2012). However, our data differs significantly from that of Goutman (2012) with rat inner hair cells because our evoked EPSCs during a sine wave stimulus are mostly monophasic and sometimes fail completely. Thus, they are less likely to summate (Figure 5 and Fig. S1). Our in vitro EPSCs and spikes also have high V.S. (0.5–0.6 for 400 Hz), which is similar to in vivo sound-evoked spikes (V.S. = 0.6–0.7 for 400 Hz; Hillery and Narins, 1987). Furthermore, we stimulated hair cells at their characteristic frequency, at physiological temperatures, and we use adult animals that are specialized to hear at low frequencies (i.e. from 100 to 1200 Hz).

EPSP summation and the importance of failures

Figure 5A shows that even during large amplitude sine wave stimulation complete EPSC failure is a prominent feature of the synapse. This occurs in spite of the large and unfailing Ca2+ currents. However, an increase in sine wave amplitude from 5 to 20 mV does lead to less EPSC failures on a cycle-by-cycle basis. This relatively high degree of EPSC failure, however, does not compromise the transmission of frequency (or pitch) information because the phase-locked spikes that do occur already contain this information. Moreover, firing spikes at every cycle during a high-frequency sine wave stimulus would be energetically costly. So the fact that spikes skip some cycles permits phase-locking to still occur while ATP consumption is reduced.

The fast EPSC kinetics, together with frequent EPSC failures, also helps to minimize the summation of closely spaced EPSPs during a high frequency sine wave stimulus. This summation can trigger spikes (Figure 1; Schnee et al., 2012), and these spikes may degrade the quality of phase-locking. Frequent EPSP failures may thus improve phase-locking by allowing the EPSP to fully decay back to baseline. Finally, a period of EPSP and spike failure, also allows time for recovery from spike refractoriness (Fig. S2). In summary, brief and large amplitude EPSPs, that sometimes skip stimulation cycles, make the hair cell synapse well suited for transmitting phase locked spikes for prolonged stimulation periods.

Multiquatal EPSCs enhance spike phase-locking

Evoked EPSCs in γ-DGG had a highly skewed distribution towards larger EPSCs (Figure 6C), suggesting that large EPSCs are due to more glutamate release, presumably due to multiquantal release. During sine wave stimulation most EPSCs exhibited a fast monophasic rise and decay (Figure 5 and Fig. S1). These phasic EPSCs with rise times of 0.2 ms likely originate from a single ribbon-type active zone and not from the coincident release of vesicles from different ribbons (Li et al., 2009). Only a few evoked EPSC events exhibited multiphasic rise times that may originate from the release of vesicles from different ribbons, although in mammals these events can also arise from single ribbons (Grant et al., 2010). The coincident release of multiple vesicles from a single synaptic ribbon produces a fast and large EPSC that enhances phase locking at auditory afferent fibers in an analogous manner perhaps to the way coincident presynaptic inputs enhance phase-locking at postsynaptic bushy cells of the cochlear nucleus (Joris et al., 1994; Carr et al., 2001).

Why are large evoked EPSCs better phase-locked than small EPSCs? One possible mechanism is that some small EPSCs are spontaneous so that their timing is random, which decreases the synchronization of small EPSCs as a group. While this is unlikely to account for all the difference according to our calculations (see last paragraph of Results), we cannot completely rule this out. The difference between small and large EPSCs can also be explained if docked synaptic vesicles act as diffusion barriers to boost nanodomain Ca2+ levels (Graydon et al., 2011). Small EPSCs may then arise from ribbons not fully packed with vesicles, where the effective [Ca2+]i rise around the ribbons is smaller and slower given that there is more space for free Ca2+ ions to diffuse away. However, for large evoked EPSCs the ribbons are likely to be fully packed with vesicles, so for the same number of free Ca2+ ions, the effective [Ca2+]i rise is higher and faster because there is very limited space for Ca2+ ion diffusion.

In summary, a fundamental reason for endowing hair cells with the ability to exocytose a sub-group of docked vesicles in a highly synchronous manner is to generate large phasic EPSPs that trigger spikes that are better synchronized to a sinewave stimulus. Highly synchronous multiquantal release thus represents an elegant mechanism to transmit the timing of sound evoked signals at the first chemical synapse for hearing.

Experimental Procedures

Animal handling procedures followed OHSU approved IACUC protocols. Adult bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) were sedated in ice bath for ~25 minutes, then double-pithed and decapitated. Amphibian papillae were carefully isolated and placed in a recording chamber containing Ringer’s solution. Hair cells and their connection with afferent fibers were exposed by procedures described previously by Keen and Hudspeth (2006) and Li et al (2009). The recording chamber, together with the preparation, was placed to an upright microscope (Axioskop 2; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and viewed with differential interference contrast optics through a 40× water-immersion objective coupled with a 1.6 magnification lens and a CCD camera (C79; Hamamatsu, Tokyo, Japan). The preparation was perfused continuously (2–3 ml/min) with Ringer’s solution containing (in mM): 95 NaCl, 2 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 3 Glucose, 1 creatine, 1 sodium pyruvate, pH adjusted to 7.30 with NaOH, and continuously bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Chemicals and salts were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Patch-clamp recordings were made with an EPC-9/2 or an EPC-10/2 (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany) patch-clamp amplifier and Pulse software (HEKA). Cells were held at −90 mV (unless otherwise indicated) and the current signal was low-pass filtered at 2 kHz and sampled at 20 kHz or higher. Off-line analysis was performed mainly with Igor Pro 5.0 software (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Custom-made macros were built using IGOR for the detection of EPSC and EPSP events and for the phase-locking analysis. Patch pipettes were pulled from thick-walled borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) using a Narishige puller (Tokyo, Japan; model PP-830) or a Sutter Puller (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA; model P-97). The internal patch pipette solution contained (in mM): 80 Cs-gluconate, 20 CsCl, 10 TEA-Cl, 10 HEPES, 2 EGTA, 3 Mg-ATP and 0.5 Na-GTP (adjusted to pH 7.3 with CsOH). This solution allowed us to isolate the hair cell Ca2+ current. The Ca2+ current was not leak subtracted because leak currents were generally <20 pA. For current clamp recordings, Cs and TEA were substituted with equal molar of K+. The liquid junction potential was estimated to be ~10 mV and compensated off-line. Whole-cell series resistance (Rs) was 23.1 ± 9.6 MΩ (n=33) and 27.0 ± 11.1 MΩ (n=22) for hair cells and afferent fibers, respectively. In 5 afferent fibers held at −90 mV, we recorded spontaneous EPSCs before and after series resistance compensation (50% to 70%). No significant changes were observed for peak amplitudes (124 ± 34 pA vs. 159 ± 54 pA), charge transferred (152 ± 58 fC vs. 170 ± 69 fC), or for 10 to 90% rise time (0.27 ± 0.01 ms vs. 0.26 ± 0.02 ms; n=5).

The input resistance (Rinput) of the afferent fibers was calculated from current-clamp recordings of the average voltage change produced by steps of negative current (5 steps, −50 to −250 pA) injected into the afferent fibers. The steady-state voltages were measured for all steps and plotted against the current amplitude. The data was fit to a straight line, whose slope was equal to Rinput. In 7 afferent fibers, the average whole-cell capacitance was 9.0 ± 1.9 pF based on the C-slow compensation of the amplifier. Then we turned off C-slow compensation and recorded capacitive currents in response to 10 mV hyperpolarizations with minimal filtering. We calculated the whole-cell capacitance by integrating the transient currents within a 30 ms time window and dividing the integral by the voltage change of 10 mV. Using this method, the whole-cell capacitance was determined to be 42.9 ± 16.9 pF from the same 7 afferent fibers. The long axon of the afferent fiber terminal thus makes a large contribution to the total afferent fiber capacitance for long integration times (Borst and Sakmann, 1998).

To determine the characteristic or resonant frequency of hair cells a step current was injected under current-clamp. The voltage response data was then fit to the following function:

where A is the amplitude of voltage oscillation, f is the characteristic frequency, ϕ is the phase, τ is the single exponential decay time constant and Vss is the steady-state membrane potential (Crawford and Fettiplace, 1981; Catacuzzeno et al., 2003). The quality factor of the electrical resonance is defined as Q = [(π·f·τ)2 + 0.25]1/2 following the model for electrical resonance of Crawford and Fettiplace (1981).

To quantify phase-locking, we calculated vector strength or synchronization index according the following equation:

where θ1, θ2, θ3, … θn are phases from spikes, EPSPs or EPSCs. This parameter varies from 0 to 1. The significance of phase-locking was tested with the Rayleigh test of circular data using a likelihood factor: L=2·n·(V.S.)2, where n=number of spikes and V.S.=vector strength. The null hypothesis is a uniform distribution of events (i.e. randomly occurring events with no phase-locking). If L>13.8, the null hypothesis is rejected at the p<0.001 significance level (Hillery and Narins, 1987). For example, a data sample of spikes with a V.S.= 0.2 is considered to still be phase-locked if the number of spikes is >200.

Statistic tests were performed with Igor Pro 6.0 (WaveMetrics) software. We used Student’s t-test for single comparisons and one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis for multiple comparisons. For either test, N.S. means p>0.05, * means p<0.05, ** means p<0.01, *** means p<0.001.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

In vitro paired recordings of auditory hair cell synapses can recapitulate in vivo afferent fiber recordings of sound-evoked action potential spikes.

The average EPSC amplitude depends linearly on Ca2+ current, but exclusion of EPSC failures leads to Ca2+ current independent EPSCs.

Like in vivo spikes, the preferred EPSC phase is stimulus level independent.

EPSPs and spikes have similar synchronization index to a sine wave stimulus.

Large multiquantal EPSCs are better phase-locked than small, evoked EPSCs.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a K99/R00 NIH award to G.-L. L., a DRF grant to S.C., and NIDCD grant DC004274 to H.v.G.. We thank Paul Brehm, Craig Jahr, Joe Trapani, Larry Trussell, Evan Vickers and Hui Zhang for instructive discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson DJ, Rose JE, Hind JE, Brugge JF. Temporal position of discharges in single auditory nerve fibers within the cycle of a sine-wave stimulus: frequency and intensity effects. J Acoust Soc Am. 1971;49:1131–1139. doi: 10.1121/1.1912474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avissar M, Furman AC, Saunders JC, Parsons TD. Adaptation reduces spike-count reliability, but not spike-timing precision, of auditory nerve responses. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6461–6472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5239-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutner D, Voets T, Neher E, Moser T. Calcium dependence of exocytosis and endocytosis at the cochlear inner hair cell afferent synapse. Neuron. 2001b;29:681–690. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Calcium current during a single action potential in a large presynaptic terminal of the rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1998;506:143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.143bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buran BN, Strenzke N, Neef A, Gundelfinger ED, Moser T, Liberman MC. Onset coding is degraded in auditory nerve fibers from mutant mice lacking synaptic ribbons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7587–7597. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0389-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CE, MacLeod KM. Microseconds matter. PLoS Biology. 2010;8:e1000405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CE, Soares D, Parameshwaran S, Perney T. Evolution and development of time coding systems. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:727–733. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(01)00276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catacuzzeno L, Fioretti B, Perin P, Franciolini F. Frog saccular hair cells dissociated with protease VIII exhibit inactivating BK currents, K(v) currents, and low-frequency electrical resonance. Hear Res. 2003;175:36–44. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00707-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey DP, Hudspeth AJ. Analysis of the microphonic potential of the bullfrog’s sacculus. J Neurosci. 1983;3:942–961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-05-00942.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. The frequency selectivity of auditory nerve fibers and hair cells in the cochlea of the turtle. J Physiol. 1980;306:79–125. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. An electrical tuning mechanism turtle cochlear hair cells. J Physiol. 1981;312:377–412. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Li GL, von Gersdorff H. Recovery from short-term depression and facilitation is ultrafast and Ca2+ dependent at auditory hair cell synapses. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5682–5692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5453-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen-Dalsgaard J, Jorgensen MB, Kanneworff M. Basic response characteristics of auditory nerve fibers in the grassfrog (Rana temporaria) Hear Res. 1998;119:155–163. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulon D, Safieddine S, Jones SM, Petit C. Otoferlin is critical for a highly sensitive and linear calcium-dependent exocytosis at vestibular hair cell ribbon synapses. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10474–10487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1009-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank T, Khimich D, Neef A, Moser T. Mechanisms contributing to synaptic Ca2+ signals and their heterogeneity in hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4483–4488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813213106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs PA. Time and intensity coding at the hair cell’s ribbon synapse. J Physiol. 2005;566(1):7–12. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.082214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler CD. Further results with the ‘uniquantal EPSP’ hypothesis. Hear Res. 1997;114:43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleich O, Narins PM. The phase response of primary auditory afferents in the songbird (Sturnus vulgaris L.) Hear Res. 1988;32:81–92. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowatzki E, Fuchs PA. Transmitter release at the hair cell ribbon synapse. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:147–154. doi: 10.1038/nn796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutman JD. Transmitter release from cochlear hair cells is phase locked to cyclic stimuli of different intensities and frequencies. J Neurosci. 2012;32:17025–17035. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0457-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutman JD, Glowatzki E. Time course and calcium dependence of transmitter release at a single ribbon synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16341–16346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705756104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant L, Yi E, Glowatzki E. Two modes of release shape the postsynaptic response at the inner hair cell ribbon synapse. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4210–4220. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4439-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graydon CW, Cho S, Li GL, Kachar B, von Gersdorff H. Sharp Ca2+ nanodomains beneath the ribbon promote highly synchronous multivesicular release at hair cell synapses. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16637–16650. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1866-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graydon CW, Cho S, Diamond JS, Kachar B, von Gersdorff H, Grimes WN. Specialized postsynaptic morphology enhances neurotransmitter dilution and high-frequency signaling at an auditory synapse. J Neurosci. 2014;34:8358–8372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4493-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberger R, Heinemann C, Neher E, Matthews G. Calcium dependence of the rate of exocytosis in a synaptic terminal. Nature. 1994;371:513–515. doi: 10.1038/371513a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillery CM, Narins PM. Neurophysiological evidence for a traveling wave in the amphibian inner ear. Science. 1984;225:1037–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.6474164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillery CM, Narins PM. Frequency and time domain comparison of low-frequency auditory fiber responses in two anuran amphibians. Hear Res. 1987;25:233–248. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt JR, Eatock RA. Inwardly rectifying currents of saccular hair cells from the leopard frog. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:1484–1502. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.4.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Forge A, Knipper M, Munkner S, Marcotti W. Tonotopic variation in the calcium dependence of neurotransmitter release and vesicle pool replenishment at mammalian auditory ribbon synapses. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7670–7678. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0785-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Franz C, Kuhn S, Furness DN, Ruttiger L, Munkner S, Rivolta MN, Seward EP, Herschman HR, Engel J, Knipper M, Marcotti W. Synaptotagmin IV determines the linear Ca2+ dependence of vesicle fusion at auditory ribbon synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:45–52. doi: 10.1038/nn.2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris PX, Carney LH, Smith PH, Yin TCT. Enhancement of neural synchronization in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus. I. Responses to tones at the characteristic frequency. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1022–1036. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.3.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen EC, Hudspeth AJ. Transfer characteristics of the hair cell's afferent synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5537–5542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601103103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MH, Li GL, von Gersdorff H. Single Ca2+ channels and exocytosis at sensory synapses. J Physiol. 2013;591:3167–3178. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.249482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köppl C. Phase locking to high frequencies in the auditory nerve and cochlear nucleus magnocellularis of the barn owl, Tyto alba. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3312–3321. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03312.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Keen E, Andor-Ardo D, Hudspeth AJ, von Gersdorff H. The unitary event underlying multiquantal EPSCs at a hair cell’s ribbon synapse. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7558–7568. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0514-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis ER, Leverenz EL, Koyama H. The tonotopic organization of the bullfrog amphibian papilla, an auditory organ lacking a basilar membrane. J Comp Physiol. 1982;145:437–455. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman LD, Wang H, Liberman MC. Opposing gradients of ribbon size and AMPA receptor expression underlie sensitivity differences among cochlear-nerve/hair-cell synapses. J Neurosci. 2011;31:801–808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3389-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC, Kiang NYS. Single-neuron labeling and chronic cochlear pathology. IV: Stereocilia damage and alterations in rate- and phase-level functions. Hear Res. 1984;16:75–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorteije JA, Rusu SI, Kushmerick C, Borst JGG. Reliability and precision of the mouse calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13770–13784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3285-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA, Köppl C, Yates GK. Activity of primary auditory neurons in the cochlear ganglion of the emu Dromaius novaehollandiae: spontaneous discharge, frequency tuning, and phase locking. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;101:1560–1573. doi: 10.1121/1.418273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews G, Fuchs P. The diverse roles of ribbon synapses in sensory neurotransmission. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:812–822. doi: 10.1038/nrn2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Sakaba T. Multiple roles of calcium ions in the regulation of neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 2008;59:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel D, McGinley MJ, Cao X-J. Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Elsevier; 2009. Temporal processing in the auditory pathway; pp. 909–919. [Google Scholar]

- Paolini AG, FitzGerald JV, Burkitt AN, Clark GM. Temporal processing from the auditory nerve to the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body in the rat. Hear Res. 2001;159:101–116. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AR, Russell IJ. Phase-locking in the cochlear nerve of the guinea-pig and its relation to the receptor potential of inner hair-cells. Hear Res. 1986;24:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(86)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AR, Shackleton TM. Variation in the phase of response to low-frequency pure tones in the guinea pig auditory nerve as function of stimulus level and frequency. JARO. 2008;10:233–250. doi: 10.1007/s10162-008-0151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SH, Salvi JD, Ó Maoiléidigh D, Hudspeth AJ. Frequency-selective exocytosis by ribbon synapses of hair cells in the bullfrog's amphibian papilla. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13433–13438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1246-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitchford S, Ashmore JF. An electrical resonance in hair cells of the amphibian papilla of the frog Rana temporaria. Hear Res. 1987;27:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Brugge JF, Anderson DJ, Hind JE. Phase-locked response to low-frequency tones in single auditory nerve fibers of the squirrel monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1967;30:769–793. doi: 10.1152/jn.1967.30.4.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell IJ, Sellick PM. Low-frequency characteristics of intracellularly recorded receptor potentials in guinea-pig cochlear hair cells. J Physiol. 1983;338:179–206. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford MA, Roberts WM. Frequency selectivity of synaptic exocytosis in frog saccular hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2898–2903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511005103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford MA, Chapochnikov NM, Moser T. Spike encoding of neurotransmitter release timing by spiral ganglion neurons of the cochlea. J Neurosci. 2012;32:4773–4789. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4511-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safieddine S, El-Amraoui A, Petit C. The auditory hair cell ribbon synapse: from assembly to function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:509–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnee ME, Lawton DM, Furness DM, Benke TA, Ricci AJ. Auditory hair cell-afferent fiber synapses are specialized to operate at their best frequencies. Neuron. 2005;47:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnee ME, Lawton DM, Furness DM, Benke TA, Ricci AJ. Response properties from turtle auditory hair cell afferent fibers suggest spike generation is driven by synchronized release both between and within synapses. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110:204–220. doi: 10.1152/jn.00121.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Neher E. Intracellular calcium dependence of transmitter release rates at a fast central synapse. Nature. 2000;406:889–893. doi: 10.1038/35022702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LL, Matthews PJ, Golding NL. Posthearing developmental refinement of temporal processing in principal neurons of the medial superior olive. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7887–7895. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1016-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JH. Spontaneous synaptic potentials from afferent terminals in the guinea pig cochlea. Hear Res. 1992;59:85–92. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90105-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons DD, Bertolotto C, Leong M. Synaptic ultrastructure within the amphibian papilla of Rana pipiens pipiens: rostrocaudal differences. Aud Neurosci. 1995;1:183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JH, Lassova L, Vardi N, Diamond JS. Coordinated multivesicular release at a mammalian ribbon synapse. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:826–833. doi: 10.1038/nn1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smotherman MS, Narins PM. The electrical properties of auditory hair cells in the frog amphibian papilla. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5275–5292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05275.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smotherman MS, Narins PM. Hair cells, hearing, and hopping: A field guide to hair cell physiology in the frog. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:2237–2246. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.15.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songer JE, Eatock RA. Tuning and timing in mammalian type I hair cells and calyceal synapses. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3706–3724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4067-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gersdorff H, Sakaba T, Berglund K, Tachibana M. Submillisecond kinetics of glutamate release from a sensory synapse. Neuron. 1998;21:1177–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SA, Preuss T, Faber DS. Phase encoding in the Mauthner system: Implications in left-right sound source discrimination. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3431–3441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3383-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittig JH, Parsons TD. Synaptic ribbon enables temporal precision of hair cell afferent synapse by increasing the number of readily releasable vesicles: a modeling study. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100(4):1724–1739. doi: 10.1152/jn.90322.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi E, Roux I, Glowatzki E. Dendritic HCN channels shape excitatory postsynaptic potentials at the inner hair cell afferent synapse in the mammalian cochlea. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:2532–2543. doi: 10.1152/jn.00506.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenisek D, Horst NK, Merrifield C, Sterling P, Matthews G. Visualizing synaptic ribbons in the living cell. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9752–9759. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2886-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.