Significance

Pregnant women are subject to increased morbidity and mortality after influenza-virus infection. Pregnancy-induced suppression of the cellular immune system to promote fetal tolerance has been suggested as a potential mechanism. Here, we report that, whereas pregnant women indeed have decreased natural killer (NK)- and T-cell functional responses after nonspecific stimulation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin, they have significantly increased NK- and T-cell responses to influenza virus compared with nonpregnant women. Intriguingly, these differences were present prior to influenza vaccination and were further enhanced after vaccination. Collectively, our data suggest a model in which an enhanced inflammatory response to influenza during pregnancy results in additional pathology in pregnant women, providing a potential explanation for their disproportionate morbidity and mortality.

Abstract

Pregnant women experience increased morbidity and mortality after influenza infection, for reasons that are not understood. Although some data suggest that natural killer (NK)- and T-cell responses are suppressed during pregnancy, influenza-specific responses have not been previously evaluated. Thus, we analyzed the responses of women that were pregnant (n = 21) versus those that were not (n = 29) immediately before inactivated influenza vaccination (IIV), 7 d after vaccination, and 6 wk postpartum. Expression of CD107a (a marker of cytolysis) and production of IFN-γ and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP) 1β were assessed by flow cytometry. Pregnant women had a significantly increased percentage of NK cells producing a MIP-1β response to pH1N1 virus compared with nonpregnant women pre-IIV [median, 6.66 vs. 0.90% (P = 0.0149)] and 7 d post-IIV [median, 11.23 vs. 2.81% (P = 0.004)], indicating a heightened chemokine response in pregnant women that was further enhanced by the vaccination. Pregnant women also exhibited significantly increased T-cell production of MIP-1β and polyfunctionality in NK and T cells to pH1N1 virus pre- and post-IIV. NK- and T-cell polyfunctionality was also enhanced in pregnant women in response to the H3N2 viral strain. In contrast, pregnant women had significantly reduced NK- and T-cell responses to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin. This type of stimulation led to the conclusion that NK- and T-cell responses during pregnancy are suppressed, but clearly this conclusion is not correct relative to the more biologically relevant assays described here. Robust cellular immune responses to influenza during pregnancy could drive pulmonary inflammation, explaining increased morbidity and mortality.

Pregnant women experience increased morbidity and mortality as a result of multiple viral infections, including influenza, hepatitis E, varicella, and measles (1, 2). Increased influenza morbidity and mortality among pregnant women is particularly well-defined after influenza pandemics but is also described with seasonal influenza (3, 4). For instance, in the 1918 influenza pandemic, a case series described mortality rates of 27% in pregnant women compared with 1% in the general population, and, in the 1957 pandemic, 50% of influenza deaths among reproductive aged women in Minnesota were in those that were pregnant (5, 6). During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, although pregnant women constituted only ∼1% of the population, they accounted for 5–7% of the deaths, hospitalizations, and intensive care unit admissions, with increased risk observed in the second and third trimesters (7, 8). Pregnant women and women planning to become pregnant have therefore been identified as a priority group to receive the influenza vaccine; however, only 50% of pregnant women or women who planned to become pregnant during the influenza season received the vaccine in 2012 (9).

The mechanisms behind this morbidity and mortality in pregnant women remain poorly understood although immune modulation required for fetal tolerance may contribute to the poor outcomes. For instance, suppression of T-cell and natural killer (NK)-cell responses by regulatory T cells during pregnancy is linked to amelioration of certain autoimmune diseases (10–12). In addition, NK and T cells from pregnant women exhibit decreased interferon (IFN)-γ and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β production in response to interleukin (IL)-12/15 stimulation or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin (PMA/I) (13–16). Prior work has also suggested a systemic type 2 T helper (Th2) bias as pregnancy progresses (17, 18). Although each of these immune alterations could compromise viral immunity, they are likely an oversimplification because recent longitudinal studies in humans report a complex inflammatory environment during pregnancy, in which both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines are increased in concentration (14). Furthermore, increased frequencies of monocytes and dendritic cells were observed whereas NK-cell and T-cell frequencies and functions decreased (13).

How these pregnancy-associated immune alterations affect antiviral responses has not been comprehensively examined. Pregnant women appear to have an adequate, although in some cases reduced, antibody response to inactivated influenza vaccination (IIV) (19, 20). Plasmacytoid dendritic cells from pregnant women produce less IFN-α in response to influenza in vitro, suggesting an impaired innate immune response (21, 22). T-cell and NK-cell responses are critical for the control and clearance of influenza virus (23–28) but have not been examined in humans during pregnancy. In murine models, influenza infection leads to increased mortality in pregnant compared with nonpregnant mice (29, 30). However, data are conflicting as to whether the increase in mortality is due to a deficiency in cellular immunity or to an overly robust immune response of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that drives cellular infiltration and airspace disease (29–31). In nonpregnant mice, there is emerging data suggesting that fatal influenza is indeed secondary to excessive chemokine production and recruitment of innate immune cells, the attenuation of which improves survival without increasing viral spread (32).

NK and T cells are also important in generating protective responses to IIV, and influenza vaccination has proven to be a useful surrogate to evaluate the NK- and T-cell immune response to influenza virus in humans (33–35). This approach has not yet been applied to pregnant women. Here, we explore whether pregnancy modifies the NK-cell and T-cell chemokine, cytokine, and cytolytic responses to 2009 pH1N1 and 2011 H3N2 virus by evaluating baseline, postvaccination, and postpartum NK- and T-cell responses in pregnant and nonpregnant women.

Methods

Participants and Study Design.

Twenty-five healthy pregnant women were recruited between October 2012 and March 2013 from the Obstetrics Clinic at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford University immediately before receiving IIV as part of their routine prenatal care. Twenty-one women completed the study. Pregnant women receiving IIV in the second and third trimester only were recruited because increased influenza morbidity and mortality attributed to pregnancy are most well-established during this period. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 29 nonpregnant (control) women were collected at Stanford’s Clinical and Translational Research Unit as part of annual seasonal influenza vaccine studies during the 2010–2011 (n = 11), 2011–2012 (n = 7), and 2012–2013 (n = 11) influenza seasons. All participants received the seasonal IIV vaccine for the given year, which included A/California/7/2009 (pH1N1) virus in all years, and H3N2 strains A/Perth/16/2009 in 2010–2012 and A/Victoria/361/2011 in 2012–2013. Venous blood was collected before vaccination to assess baseline NK- and T-cell functions and, 7 d after vaccination, to assess the effect of the vaccine prime on NK- and T-cell functions, in both pregnant and control participants. Pregnant participants were also evaluated ∼6 wk postpartum. All participants were females aged 18–42 y. Exclusion criteria for all participants included concomitant illnesses, immunosuppressive medications, or receipt of blood products within the previous year. Pregnant women were also excluded for known fetal abnormalities and morbid obesity (prepregnancy body mass index > 40). This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board; written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

PBMC Isolation.

PBMCs were isolated from whole blood by Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) by the Stanford University Clinical and Translational Research Unit Laboratory and cryopreserved in 90% (vol/vol) FBS (Thermo Scientific) plus 10% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich).

PBMC Infection and Stimulation.

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed and washed with RPMI (Thermo Scientific) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS (Thermo Scientific) and 50 U/mL benzonase (EMD Millipore), and then washed and resuspended in serum-free media at 1.5 × 106 per 100 µL. Infection with 2009 pH1N1 wild-type virus and A/Victoria/361/2011 (H3N2) wild-type virus (kindly provided by Kanta Subbarao, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda) was performed at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3 for 1 h at 37° C with 5% carbon dioxide. After 1 h, 100 µL of RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS (RP10) was then added for 2 h. The plate was then spun at 750 × g and resuspended in RP10 with 2 μM monensin, 3 μg/mL brefeldin A (eBiosciences), and anti-CD107a-allophycocyanin-H7 (BD Pharmingen) for 4 h. PMA/I (eBiosciences) was added to positive control wells. EDTA (Hoefer) was added to 1.66 mM for 10 min to arrest stimulation.

Cell Staining and Flow-Cytometric Analysis.

Cells were stained with LIVE/DEAD fixable Aqua Stain (Life Technologies) and then fixed and permeabilized with FACS Lyse and FACS Perm II (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were stained with anti-CD3-phycoerythrin-Cy7, anti-CD8-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-IFN-γ-allophycocyanin, anti-MIP-1β-phycoerythrin, Granzyme B-violet-450 (BD Pharmingen), and anti-CD7-fluorescein isothiocyanate (BioLegend) and fixed using 1% paraformaldehyde. Uncompensated data were collected using a four-laser LSR-II using the following configuration: http://facs.stanford.edu/lsr2_config. Analysis and compensation were performed using FlowJo flow-cytometric analysis software, version 9.7.5 (Tree Star). All functional values were background subtracted by the negative control. Individual samples were excluded from the functional analysis if the number of NK, CD4+, or CD8+ T cells was less than 200.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism, version 6.0d (GraphPad Software). Pregnant and control participant characteristics were compared using Mann–Whitney U Tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for discreet variables. Functional results were compared between groups using Mann–Whitney U tests, and longitudinal data within groups were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The data analysis program Simplified Presentation of Incredibly Complex Evaluations (SPICE; version 5.35; M. Roederer, Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health) was used to generate graphical displays of polyfunctionality.

Results

Cohort Demographics.

Demographics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. The average age of the pregnant (30.1 ± 5.8 y) and control (27.6 ± 5.9 y) women was not significantly different. A significantly lower proportion of pregnant women (43%) than control women (76%) had received a seasonal influenza vaccine in the prior year by self report (P = 0.02). Pregnant women were nearly equally divided between the second and third trimesters at the time of enrollment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics

| Characteristic | Pregnant, N = 21 | Control, N = 29 | Statistic |

| Age, y (median) | 30.0 | 27.4 | P = 0.07 |

| White, n (%) | 4 (19) | 11 (37) | |

| Asian, n (%) | 4 (19) | 6 (21) | |

| Latina, n (%) | 9 (43) | 6 (21) | |

| Race, other, n (%) | 4 (19) | 6 (21) | |

| Vacc. last year, n (%) | 9 (43) | 22 (76) | P = 0.02 |

| Trimester 2, n (%) | 10 (48) | ||

| Trimester 3, n (%) | 11 (52) |

Assessment of NK-Cell, CD8+ T-Cell, and CD4+ T-Cell Frequency Pre- and Post-IIV.

To assess whether pregnancy was associated with alterations in the frequency of NK and T cells pre- or postvaccination, NK cells and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were identified (Fig. 1A). The frequency of NK cells, CD8+ T cells, or CD4+ T cells did not significantly differ between pregnant and control groups pre- or postvaccination (Fig. 1B). Vaccination did not result in a significant change in the proportion of NK-cell, CD8+ T-cell, or CD4+ T-cell populations in either the pregnant or control group. In addition, there was no change in NK-cell, CD8+ T-cell, or CD4+ T-cell frequencies in pregnant women compared with postpartum (Fig. 1C). Therefore, the frequency of NK cells, CD8+ T cells, or CD4+ T cells was not significantly altered by either IIV or pregnancy.

Fig. 1.

NK- and T-cell frequencies in pregnant and control women. (A) Gating strategy to define NK- and T-cell populations, using CD7 to define NK cells (51). FSC, forward scatter; SSC, side scatter; Avid, aqua live/dead viability dye. (B) NK, CD8+, and CD4+ cell frequencies in pregnant (P) and control (C) women at day 0 and day 7. Error bars reflect the median and interquartile range. (C) NK-cell, CD8+ T-cell, and CD4+ T-cell frequencies in pregnant women at day 0, day 7, and 6 wk postpartum (PP).

Robust Inflammatory Responses to Influenza A Virus in Pregnant Women.

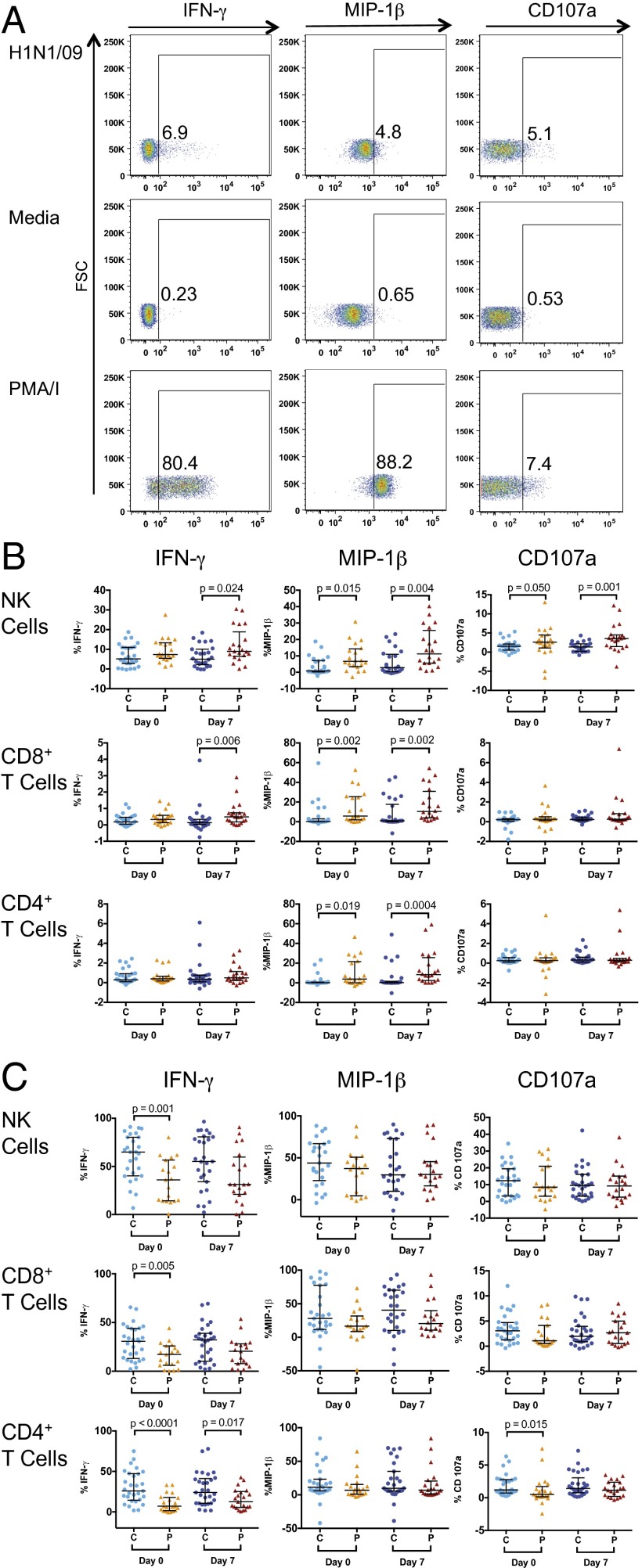

To assess NK- and T-cell functional responses to influenza-virus infection, we modified an assay previously described by He et al. and Long et al. (33, 35, 36). PBMCs were incubated with influenza virus, resulting in infection of 60–70% of monocytes (Fig. S1). Functional responses in NK cells and T cells were evaluated in pregnant and nonpregnant women immediately before and after vaccination (Fig. 2A). Prevaccination responses reflect intrinsic NK-cell responses and those of preexisting memory T cells whereas day 7 postvaccination responses reflect any additional response, or priming, generated by IIV. Immediately before vaccination, a higher percentage of NK cells in pregnant women produced MIP-1β to pH1N1 virus [median, 6.66 vs. 0.90% (P = 0.015)] and expressed CD107a, a marker of cytolysis [median, 2.61 vs. 1.53% (P = 0.05)] after pH1N1 virus stimulation in vitro (Fig. 2B). On day 7 postvaccination, the differences in NK-cell functional responses between the pregnant and control groups were more dramatic, with increased production of IFN-γ [median, 8.96 vs. 5.02% (P = 0.024)], MIP-1β [median, 11.23 vs. 2.81% (P = 0.004)], and CD107a expression [median, 3.57 vs. 1.35% (P = 0.001)] (Fig. 2B). Pregnant women also demonstrated increased MIP-1β production in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells prevaccination and on day 7 and increased production of IFN-γ in CD8+ T cells at day 7 compared with nonpregnant women (Fig. 2B). Responses to H3N2 virus were qualitatively different from those to pH1N1, with higher frequencies of IFN-γ–producing NK and T cells and lower frequencies of MIP-1β–producing T cells (Table S1). Although responses to H3N2 appeared to be somewhat higher in pregnant women, these differences were far less dramatic and generally not significant (Fig. S2A). Excluding controls from 2010 and 2011, to account for H3N2 vaccine strain differences, did not dramatically change these findings (Fig. S3A). Importantly, all of these differences were specific to influenza virus because NK cells, CD8+ T cells, and CD4+ T cells in pregnant women produced significantly less IFN-γ at baseline than controls in response to PMA/I and did not differ in MIP-1β production or CD107a expression from controls (Fig. 2C). Given differences between pregnant and control groups in prior vaccination status, we stratified the cohort based on vaccination history (Fig. S4A). Although the number of women in each group was very small, the trends for increased responses to pH1N1 virus in pregnant women remained. In particular, pregnant women who had not been vaccinated in the prior year had significantly increased MIP-1β NK- and T-cell responses to pH1N1 after vaccination compared with nonpregnant women who were also unvaccinated in the prior year (Fig. S4A).

Fig. 2.

NK- and T-cell responses to pH1N1 virus and PMA/I in pregnant women and controls. (A) Representative plots showing NK-cell IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and CD107a expression. (B) NK-cell, CD8+ T-cell, and CD4+ T-cell IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and CD107a expression after pH1N1 virus stimulation in pregnant (P) and control (C) women. (C) NK-cell, CD8+ T-cell, and CD4+ T-cell IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and CD107a expression after PMA/I stimulation. Error bars reflect the median and interquartile range.

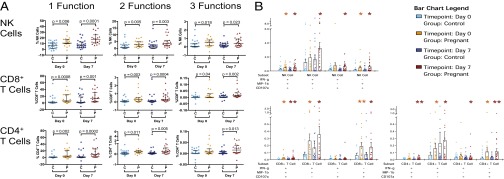

Pregnancy Is Associated with Increased Polyfunctional Cellular Responses to Influenza A Virus.

Given the increased responsiveness to pH1N1 virus in pregnant women, we examined whether pregnancy was associated with an increased frequency of NK or T cells performing multiple functions simultaneously. NK cells from pregnant women were significantly more likely to have any two functions per cell at baseline [median, 2.85% vs. 0.75% (P = 0.005)] and day 7 postvaccination [median, 3.67% vs. 1.174% (P = 0.003)] than controls (Fig. 3A). In addition, NK cells from pregnant women were more likely to perform all three functions, both at baseline [median, 0.52% vs. 0.04% (P = 0.018)] and at day 7 [median 0.41% vs. 0.13% (P = 0.023)] after vaccination (Fig. 3A). CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells were similarly more polyfunctional in pregnant women compared with controls (Figs. 3A). The various combinations of two or three functions were also consistently enhanced in pregnant women compared with controls. (Fig. 3B). We again stratified the cohort by vaccination history and found that pregnant women had more polyfunctional responses to pH1N1, regardless of vaccination history (Fig. S4B). NK and T cells in pregnant women were also significantly more polyfunctional in response to H3N2 virus (Fig. S2B), and T cells remained so when excluding controls from 2010 and 2011 (Fig. S3B). Thus, both NK cells and T cells appeared to have more polyfunctional responses to influenza A virus during pregnancy. In stark contrast to the influenza virus response, NK and T cells in pregnant women were less likely than nonpregnant controls to have multiple functions in response to PMA/I (Fig. S5).

Fig. 3.

Polyfunctional NK- and T-cell responses to pH1N1 virus in pregnant women and controls. (A) NK-cell, CD8+ T-cell, and CD4+ T-cell responses in control (C) and pregnant (P) women after pH1N1 virus stimulation to compare the following: one function (IFN-γ, MIP-1β, or CD107a), any two functions, or all three functions at day 0 and day 7. Error bars reflect the median and interquartile range. (B) All polyfunctional combinations of either IFN-γ, MIP-1β, or CD107a. Statistical differences are represented by *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.005 for differences between pregnant and controls at day 0 and day 7. Orange indicates superior responses in pregnant women at day 0, and auburn indicates superior responses in pregnant women at day 7.

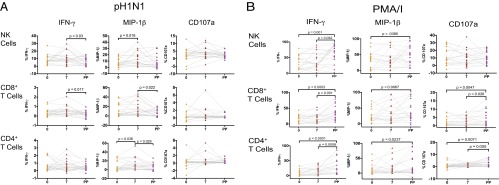

Priming and Maintenance of Influenza A Virus Responses in Pregnant Women.

Responses to pH1N1 virus in pregnant women were evaluated longitudinally (Fig. 4A). Both NK cells and CD4+ T cells demonstrated a significant increase in MIP-1β after vaccination (P = 0.016 and 0.036, respectively); however, there were no significant changes in IFN-γ production or cytolytic activity at day 7. In the postpartum period, the frequency of IFN-γ–producing NK cells (P = 0.03) and CD8+ T cells (P = 0.017) declined significantly, as did the frequency of MIP-1β–producing CD8+ cells (P = 0.022) and CD4+ T cells (P = 0.029) from the day 7 postimmunization time point. However, there were no significant differences in cytokine production or cytolytic activity between the baseline and postpartum time point. We also evaluated longitudinal responses to H3N2 virus; NK- and T-cell responses were generally not significantly influenced by vaccination or pregnancy (Fig. S2C). In contrast to the responses to influenza A viruses, there was a robust increase in production of IFN-γ and MIP-1β, and CD107a expression in NK cells, CD8+ T cells, and CD4+ T cells after stimulation with PMA/I in the postpartum period (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Longitudinal NK- and T-cell functional responses to pH1N1 virus and PMA/I in pregnant women. (A) NK-cell, CD8+ T-cell, and CD4+ T-cell IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and CD107a expression in pregnant women after pH1N1 virus stimulation at day 0, day 7, and 6 wk postpartum (PP). (B) IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and CD107a expression in pregnant women after PMA/I stimulation at day 0, day 7, and 6 wk postpartum (PP).

Effect of Pregnancy Trimester on Cellular Responses to Vaccination.

Immune responsiveness could change throughout pregnancy, and prior work has proposed a decreasing ratio of type 1 T helper (Th1) to Th2 CD4+ T cells as pregnancy progresses (37). We therefore evaluated whether there were differences in the response to pH1N1 virus between women in their second and third trimester. Before vaccination, there were no significant differences between NK cell, CD8+ T cell, or CD4+ T-cell IFN-γ or MIP-1β production between women in their second vs. third trimester (Fig. S6). However, at day 7, primed IFN-γ production was increased in NK cells (P = 0.0079) and CD4+ T cells (P = 0.0356) in women in their second trimester compared with the third trimester. This finding suggests that trimester does not impact baseline responses to pH1N1 virus but may affect the priming of NK- and T-cell responses.

Discussion

During pregnancy, alterations in systemic immunity can have dramatic effects on maternal and fetal health. It is generally believed that T- and NK-cell responses are suppressed during pregnancy, based on the marked amelioration of symptoms in subjects that have certain types of autoimmunity (10–12). Here, we performed, to our knowledge, the first evaluation of how pregnancy alters the NK- and T-cell immune responses to influenza in humans by profiling the cytokine and cytolytic responses to influenza A viruses before and after vaccination with IIV. At baseline and after vaccination, we were surprised to find that pregnant women had enhanced, not suppressed, NK- and T-cell responses to influenza A virus compared with nonpregnant women. Although the differences in production of the chemokine MIP-1β were particularly impressive in response to pH1N1 virus, pregnant women also had significantly increased frequencies of polyfunctional NK and T cells in response to both pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses. This heightened responsiveness in pregnant women was observed only with influenza A viruses because PMA/I responses were equivalent or lower in pregnant women compared with controls. These data highlight the complex changes in immune function that occur during pregnancy, in which responses to some stimuli are suppressed but others are enhanced. Collectively, our data indicate that pregnant women have increased NK- and T-cell cytokine and chemokine production in response to influenza virus in vitro. Excessive immune-cell recruitment in response to influenza virus during pregnancy may tip the balance from a healthy immune response into one that is destructive, resulting in increased disease severity.

Several lines of evidence support the idea that increased production of chemokines and cytokines in response to influenza may contribute to pathology during influenza infection. For example, overabundant chemokines have been linked to increased pathogenicity and morbidity in influenza infection in humans (38), and blockade of influenza-induced cytokines protects against influenza mortality in mice without increasing viral titers in infected tissue (39). Significantly, in murine models, influenza preferentially induces monocyte-attracting chemokines, such as MIP-1β (40). Mice deficient in MIP-1α, another CC chemokine with similar functional properties to MIP-1β, have less influenza-induced pneumonitis despite delayed viral clearance (41). In humans, MIP-1β levels correlate with severity of influenza symptoms and viral replication, and rise with similar kinetics after influenza infection with other CC chemokines (42, 43). In pregnant women, IFN-α and IFN-λ production are decreased compared with controls when PBMCs are cocultured with influenza (21, 22). Diminished interferon production may result in higher viral titers and increased production of CC-chemokines in vivo, resulting in more inflammation and increased morbidity. Pregnant women have also been shown to have decreased IgG subclass 2 production during influenza infection, which has been associated with severe disease and cytokine dysregulation (44–46). Thus, our detection of elevated percentages of MIP-1β–producing NK cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells in pregnant women in response to influenza A viruses, and pH1N1 virus in particular, but not nonspecific stimulation with PMA/I, suggests a possible mechanism for increased disease severity in pregnant women.

CC chemokines such as MIP-1β appear to have dual roles during pregnancy. In addition to their roles in recruiting immune cells during infection, CC chemokines are important in both placentation and parturition. MIP-1α is produced by cytotrophoblasts in the placenta to recruit large quantities of monocytes and NK cells to the uterine decidua during pregnancy (47). Chemokines are also up-regulated, and systemic leukocytes demonstrate increased chemotactic responsiveness at parturition and perhaps before parturition as well (48, 49). In prior studies, stimulation of NK cells from pregnant women with IL-12/IL-15 was not associated with increased levels of MIP-1α or MIP-1β (13, 14). However, our own data demonstrate different responses based on the stimulation condition: the increase in MIP-1β production was observed only after infection of PBMC cultures with pH1N1 virus, and less so with H3N2 virus, but not with generalized stimulation with PMA/I. This difference is a critical distinction because nearly all in vitro evidence reporting decreased NK- and T-cell function during pregnancy has relied on such nonspecific stimulation (15, 16), which our data also demonstrate. The inflammatory response to pH1N1 and H3N2 virus was also very different, with higher frequencies of IFN-γ–producing cells after H3N2 infection but lower T-cell production of MIP-1β. This pathway will require further investigation, but an elevated chemokine response to pH1N1 may be clinically important.

In addition to the significantly enhanced chemokine production by NK and T cells in pregnant women, the increased polyfunctional nature of the NK- and T-cell responses to influenza observed here was striking, particularly given the general perception that cellular immune responses are attenuated during pregnancy (11). Increased polyfunctionality was observed in response to both pH1N1 and H3N2 viruses. Interestingly, pregnant women in their second trimester had significantly higher NK and CD4+ IFN-γ responses to pH1N1 virus on day 7 than women in the third trimester. This difference may suggest a deficit in the ability to mount a de novo adaptive immune response to influenza in vivo in the third trimester in comparison with those in the second because there was no difference in the baseline responses that would rely on innate NK and preexisting memory T-cell responses. Prior studies have reported decreased plasma IFN-γ levels during healthy pregnancy (13, 17), but circulating plasma levels in the absence of stimulation or after nonspecific stimulation may not reflect the ability to respond to a viral challenge. In fact, during infection, local levels of cytokines may be more important predictors of immune responses, and mucosal and systemic levels of cytokines are generally not correlated (50).

Although production of IFN- γ, MIP-1β, and CD107a in response to infection with pH1N1 virus in vitro generally declined after vaccination in the postpartum period, these differences were not significant compared with baseline during pregnancy. Thus, pregnancy itself did not appear to have a dramatic effect on pH1N1 virus responses within an individual, although the boosting of responses by vaccination makes it difficult to interpret these results. In fact, T- and NK-cell responses to pH1N1 virus declined between day 7 and postpartum, suggesting that significant boosting had occurred. It is also possible that 6 wk postpartum was not a sufficient interval to allow for complete normalization of immune function after pregnancy, as has been suggested previously (13), decreasing our ability to detect pregnancy-induced changes longitudinally. However, even these subtle decreases in antiviral responses postpartum are remarkable in the context of the dramatic rise in NK- and T-cell functional responses to PMA/I stimulation postpartum compared with during pregnancy. Thus, the immune changes that occur during pregnancy appear to be finely tuned to the specific stimulus.

Limitations of the study include our modest sample size, differences between groups with respect to vaccination history and vaccination year, and the fact that the effect of mock vaccination could not be evaluated. In addition, although vaccination has been used as a surrogate to study alterations in the immune responses of the elderly (34) and children (33) in comparison with adults, it remains a surrogate for a true infection. Importantly, the baseline differences between pregnant and control women were not subject to bias based on differences in vaccination product or status because these studies measured intrinsic responsiveness to pH1N1 and H3N2 virus. To confirm that enhanced responsiveness contributes to pathology during pregnancy, larger studies and evaluation of pregnant vs. nonpregnant women infected with influenza will be necessary. The fact that the differences between pregnant women and controls were more dramatic with pH1N1 virus compared with H3N2 stimulation could explain the more extraordinary increases in morbidity and mortality seen in pregnant women with influenza during pandemics compared with seasonal influenza, although this finding will also need to be followed up with larger studies.

In summary, we report that pregnant women have enhanced NK- and T-cell responsiveness to pH1N1 virus, and possibly H3N2 virus, compared with nonpregnant controls, both before and after IIV vaccination. Differences before immunization suggest that lymphocytes in pregnant women are intrinsically hyperresponsive to influenza virus in comparison with those of nonpregnant women. Importantly, these findings challenge the notion that pregnancy represents a state of suppressed cellular immune responses but instead suggest that immune responses to different challenges are differentially regulated during pregnancy. Although these data will need to be confirmed in the setting of acute influenza infection in pregnant women, the increased chemokine and cytokine production in response to influenza virus could contribute to increased pneumonitis and more severe disease secondary to influenza infection in pregnant women. If these observations hold in the setting of influenza infection, targeted chemokine and cytokine inhibition could provide a novel therapeutic intervention for patients with severe influenza.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Kronstad, PhD, for critical reading of the manuscript; Kanta Subbarao, MBBS, MPH (National Institutes of Health) for providing influenza virus; and V. Camille Roque for outstanding assistance with patient enrollment. This work was supported by Stanford Child Health Research Institute–Stanford Clinical and Translational Science Award Grants UL1 TR000093 (to A.W.K.) and T32 AI78896-05 (to A.W.K.), the Human Immunology Project Consortium (HIPC) Infrastructure and Opportunities Fund (C.A.B.), HIPC Grant U19AI090019 (to M.M.D.), Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Grant 2013099 (to C.A.B.), and a McCormick Faculty Award (to C.A.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1416569111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Jamieson DJ, Theiler RN, Rasmussen SA. Emerging infections and pregnancy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(11):1638–1643. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kourtis AP, Read JS, Jamieson DJ. Pregnancy and infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2211–2218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1213566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mak TK, Mangtani P, Leese J, Watson JM, Pfeifer D. Influenza vaccination in pregnancy: Current evidence and selected national policies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;8(1):44–52. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Uyeki TM. Effects of influenza on pregnant women and infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(Suppl 3):S3–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris JW. Influenza occurring in pregnant women: A statistical study of thirteen hundred and fifty cases. J Am Med Assoc. 1919;72:978–980. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman DW, Barno A. Deaths from Asian influenza associated with pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1959;78:1172–1175. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(59)90570-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siston AM, et al. Pandemic H1N1 Influenza in Pregnancy Working Group Pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 2010;303(15):1517–1525. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosby LG, Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ. 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in pregnancy: A systematic review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women–United States, 2012-2013 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(38):787–792. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aluvihare VR, Betz AG. The role of regulatory T cells in alloantigen tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:330–343. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erlebacher A. Mechanisms of T cell tolerance towards the allogeneic fetus. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(1):23–33. doi: 10.1038/nri3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mellor AL, Munn DH. Immunology at the maternal-fetal interface: Lessons for T cell tolerance and suppression. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:367–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraus TA, et al. Characterizing the pregnancy immune phenotype: Results of the viral immunity and pregnancy (VIP) study. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32(2):300–311. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9627-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraus TA, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine profiling during pregnancy and post-partum periods. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;64(6):411–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sacks GP, Redman CWG, Sargent IL. Monocytes are primed to produce the Th1 type cytokine IL-12 in normal human pregnancy: An intracellular flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;131(3):490–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veenstra van Nieuwenhoven AL, et al. Cytokine production in natural killer cells and lymphocytes in pregnant women compared with women in the follicular phase of the ovarian cycle. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(5):1032–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)02976-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aris A, Lambert F, Bessette P, Moutquin J-M. Maternal circulating interferon-gamma and interleukin-6 as biomarkers of Th1/Th2 immune status throughout pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(1):7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wegmann TG, Lin H, Guilbert L, Mosmann TR. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: Is successful pregnancy a TH2 phenomenon? Immunol Today. 1993;14(7):353–356. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90235-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperling RS, et al. Immunogenicity of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccination received during pregnancy or postpartum. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(3):631–639. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318244ed20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlaudecker EP, McNeal MM, Dodd CN, Ranz JB, Steinhoff MC. Pregnancy modifies the antibody response to trivalent influenza immunization. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(11):1670–1673. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forbes RL, Wark PAB, Murphy VE, Gibson PG. Pregnant women have attenuated innate interferon responses to 2009 pandemic influenza A virus subtype H1N1. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(5):646–653. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanders RL, Gibson PG, Murphy VE, Wark PAB. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and CD8 T cells from pregnant women show altered phenotype and function following H1N1/09 infection. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(7):1062–1070. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yap KL, Ada GL, McKenzie IF. Transfer of specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes protects mice inoculated with influenza virus. Nature. 1978;273(5659):238–239. doi: 10.1038/273238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMichael AJ, Gotch FM, Noble GR, Beare PA. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity to influenza. N Engl J Med. 1983;309(1):13–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307073090103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gazit R, et al. Lethal influenza infection in the absence of the natural killer cell receptor gene Ncr1. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(5):517–523. doi: 10.1038/ni1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jost S, et al. Changes in cytokine levels and NK cell activation associated with influenza. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e25060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jost S, et al. Expansion of 2B4+ natural killer (NK) cells and decrease in NKp46+ NK cells in response to influenza. Immunology. 2011;132(4):516–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Draghi M, et al. NKp46 and NKG2D recognition of infected dendritic cells is necessary for NK cell activation in the human response to influenza infection. J Immunol. 2007;178(5):2688–2698. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcelin G, et al. Fatal outcome of pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection is associated with immunopathology and impaired lung repair, not enhanced viral burden, in pregnant mice. J Virol. 2011;85(21):11208–11219. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00654-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JC, et al. Severe pathogenesis of influenza B virus in pregnant mice. Virology. 2014;448:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pazos MA, Kraus TA, Muñoz-Fontela C, Moran TM. Estrogen mediates innate and adaptive immune alterations to influenza infection in pregnant mice. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brandes M, Klauschen F, Kuchen S, Germain RN. A systems analysis identifies a feedforward inflammatory circuit leading to lethal influenza infection. Cell. 2013;154(1):197–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He XS, et al. Cellular immune responses in children and adults receiving inactivated or live attenuated influenza vaccines. J Virol. 2006;80(23):11756–11766. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01460-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kutza J, Gross P, Kaye D, Murasko DM. Natural killer cell cytotoxicity in elderly humans after influenza immunization. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996;3(1):105–108. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.1.105-108.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Long BR, et al. Elevated frequency of gamma interferon-producing NK cells in healthy adults vaccinated against influenza virus. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15(1):120–130. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00357-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He X-S, et al. T cell-dependent production of IFN-gamma by NK cells in response to influenza A virus. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(12):1812–1819. doi: 10.1172/JCI22797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamaguchi K, et al. Relationship of Th1/Th2 cell balance with the immune response to influenza vaccine during pregnancy. J Med Virol. 2009;81(11):1923–1928. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Jong MD, et al. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat Med. 2006;12(10):1203–1207. doi: 10.1038/nm1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh KB, et al. Suppression of cytokine storm with a sphingosine analog provides protection against pathogenic influenza virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(29):12018–12023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107024108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sprenger H, et al. Selective induction of monocyte and not neutrophil-attracting chemokines after influenza A virus infection. J Exp Med. 1996;184(3):1191–1196. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cook DN, et al. Requirement of MIP-1 alpha for an inflammatory response to viral infection. Science. 1995;269(5230):1583–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.7667639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen Z, et al. Host immunological response and factors associated with clinical outcome in patients with the novel influenza A H7N9 infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(8):O493–O500. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fritz RS, et al. Nasal cytokine and chemokine responses in experimental influenza A virus infection: Results of a placebo-controlled trial of intravenous zanamivir treatment. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(3):586–593. doi: 10.1086/314938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson DP, Klein SL. Pregnancy and pregnancy-associated hormones alter immune responses and disease pathogenesis. Horm Behav. 2012;62(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan JFW, et al. The lower serum immunoglobulin G2 level in severe cases than in mild cases of pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza is associated with cytokine dysregulation. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18(2):305–310. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00363-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gordon CL, et al. Association between severe pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection and immunoglobulin G(2) subclass deficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(5):672–678. doi: 10.1086/650462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drake PM, et al. Human placental cytotrophoblasts attract monocytes and CD56(bright) natural killer cells via the actions of monocyte inflammatory protein 1alpha. J Exp Med. 2001;193(10):1199–1212. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.10.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamilton SA, Tower CL, Jones RL. Identification of chemokines associated with the recruitment of decidual leukocytes in human labour: Potential novel targets for preterm labour. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e56946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gomez-Lopez N, Tanaka S, Zaeem Z, Metz GA, Olson DM. Maternal circulating leukocytes display early chemotactic responsiveness during late gestation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(Suppl 1):S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-S1-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blish CA, et al. Genital inflammation predicts HIV-1 shedding independent of plasma viral load and systemic inflammation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(4):436–440. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826c2edd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hauser A, et al. Optimized quantification of lymphocyte subsets by use of CD7 and CD33. Cytometry A. 2013;83(3):316–323. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.