Significance

It is a popular assumption that certain perceptions—for example, that highly feminine women are attractive, or that masculine men are aggressive—reflect evolutionary processes operating within ancestral human populations. However, observations of these perceptions have mostly come from modern, urban populations. This study presents data on cross-cultural perceptions of facial masculinity and femininity. In contrast to expectations, we find that in less developed environments, typical “Western” perceptions are attenuated or even reversed, suggesting that Western perceptions may be relatively novel. We speculate that novel environments, which expose individuals to large numbers of unfamiliar faces, may provide novel opportunities—and motives—to discern subtle relationships between facial appearance and other traits.

Keywords: facial attractiveness, evolution, cross-cultural, aggression, stereotyping

Abstract

A large literature proposes that preferences for exaggerated sex typicality in human faces (masculinity/femininity) reflect a long evolutionary history of sexual and social selection. This proposal implies that dimorphism was important to judgments of attractiveness and personality in ancestral environments. It is difficult to evaluate, however, because most available data come from large-scale, industrialized, urban populations. Here, we report the results for 12 populations with very diverse levels of economic development. Surprisingly, preferences for exaggerated sex-specific traits are only found in the novel, highly developed environments. Similarly, perceptions that masculine males look aggressive increase strongly with development and, specifically, urbanization. These data challenge the hypothesis that facial dimorphism was an important ancestral signal of heritable mate value. One possibility is that highly developed environments provide novel opportunities to discern relationships between facial traits and behavior by exposing individuals to large numbers of unfamiliar faces, revealing patterns too subtle to detect with smaller samples.

Inspired by evidence from nonhuman species indicating that exaggerated sex-typical traits (e.g., large antlers, peacock tails) are often attractive to mates or intimidating to rivals (1, 2), morphological sex typicality in humans (masculinity in men and femininity in women) has been the focus of considerable research into attractiveness judgments (3, 4). Facial attractiveness research has been revolutionized by this explanatory framework from the biological sciences, which proposes that attractive human faces honestly signaled mate value within ancestral environments.

An influential proposal is that facial femininity is a signal of fertility in human female faces (4–9) because, within same-age women, it is associated with estrogens (10), which, in turn, are related to measures of reproductive health (11). Like ovarian function, facial femininity declines with age in adulthood (12, 13). The proposal that fertile women should be attractive to men is seemingly uncontroversial because males who discriminatively mate with fertile females should achieve a straightforward reproductive advantage over those males who do not, with all other factors being equal (6). Although direct associations between facial femininity and fertility have not been demonstrated, the consensus from Western preferences, and from the limited cross-cultural data available, is that femininity is attractive, as predicted by the fertility hypothesis (14–17). In environments where fertility is high and variable, this relationship should be even more apparent.

In male faces, masculinity has been variously proposed to signal heritable disease resistance (“good genes” or “immunocompetence”) (4, 15, 18–22) and/or perceived as a cue of aggressiveness and, consequently, intrasexual competitiveness (22, 23). The “honesty” of face shape as an indicator of immunocompetence is proposed to be the result of an immunosuppressive effect of testosterone. Because testosterone influences the growth of sex-typical traits in many species (24, 25), masculine facial shape is proposed to be a costly, and thus honest, signal of male quality (22). The hypothesis that cues of heritable health should be attractive to females is widely accepted (26), although the evidence for a link between heritable health and masculinity in humans is tentative at best (22).

Support for a link between masculinity and aggression is largely indirect, and it consists of an association between testosterone and both aggressive behavior (27, 28) and face shape (25), in addition to the fact that honest signaling of dominance is commonly observed in nonhuman species (3). Masculine faces are perceived as aggressive in those groups (i.e., urban, Western) where the relationship has been tested (29). Because masculinity may signal both (desirable) immunity and (potentially costly) aggression in humans, some authors have proposed that preferences for masculinity reflect women trading-off benefits of traits putatively associated with health against those traits associated with prosocial behaviors, such as parental investment (23, 30, 31).

Consistent with both of these proposals, data indicate that preferences for masculinity are stronger in circumstances where indirect benefits (heritable quality) can be realized without accompanying direct costs (aggression and low paternal investment). Such circumstances include judging attractiveness in the context of a short-term (vs. a long-term) relationship (32) and in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle when conception following intercourse is most likely (33). Masculinity is also reported to be more strongly preferred in environments with relatively high pathogen burdens (19, 30) and in environments with higher local homicide rates (23), which has been interpreted as a response to variation in the benefits of heritable disease resistance (19) and in the net benefits conferred by aggressive males under varying levels of male–male competition (23).

All of this supporting evidence comes with a very important caveat; although there has been some cross-cultural work in this area (34), the majority of studies have been conducted in Western, often student, populations characterized by high levels of development and urbanization [Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic; so-called WEIRD participants (35)]. Research on preferences in other groups is scant and methodologically inconsistent, using Internet-based designs or a limited cross-cultural component (7, 15–18). Because there are differences between Western/non-Western and industrial/small-scale societies in many behaviors, including aspects of visual perception and mate choice (35), this over-representation greatly limits generalizability. Perhaps most importantly, large-scale (post)industrial societies present inhabitants with large numbers of unfamiliar faces and provide venues for the efficient exchange of (visual) social information (e.g., posters, television, Internet); these factors may be instrumental in the acquisition and reinforcement of preferences (36–39). It is possible therefore that rather than being a legacy of ancestral selection pressures, preferences for dimorphism emerge in large urban groups as a byproduct of the information-processing strategies used to process large amounts of social information or in response to arbitrary cultural norms.

Development also introduces an increased presence of highly differentiated social roles that arise from a greater division of labor, along with opportunities to acquire prestige without strength or aggression. Because partner preferences have been proposed to develop in response to sex-typical social roles (40, 41), it is possible that increasingly differentiated roles could influence masculinity preferences if desirable social roles not present in less developed groups are associated with facial appearance.

We assessed preferences for, and trait attributions made to, faces varying in dimorphism in a cross-cultural sample of 12 groups, including non-Western, nonstudent, and small-scale societies (n = 962; Table 1 and Tables S1 and S2). We tested the predictions, derived from the immunocompetence handicapping hypothesis, that (i) preferences for dimorphism will be stronger in less developed groups and (ii) masculine faces would be perceived as aggressive in all populations, with perceptions in low-development groups at least as strong as in groups with high development. We estimated social development with the Human Development Index (HDI), which is a composite indicator compiled by the United Nations Development Program. To investigate which aspects of development were associated with variation in perception of our facial stimuli, we took the World Health Organization measures of years lost to disease and United Nations (UN) measures of homicide rates as proxy measures of disease burden and male intrasexual competition, respectively (both log-transformed), and UN measures of levels of urbanization. Using these national statistics almost certainly underestimates disease burden in the small-scale societies in our sample, which is a conservative estimate with regard to our hypotheses.

Table 1.

Summary information for the groups tested

| Group | Local region | Country | Subsistence mode | n male | n female | n female after exclusions |

| Canadian students | Alberta province | Canada | Market economy | 23 | 60 | 18 |

| UK students | Bristol city | United Kingdom | Market economy | 80 | 238 | 134 |

| Shanghai students | Shanghai municipality | China | Market economy | 41 | 38 | 38 |

| Hangzhou citizens | Zhejiang province | China | Market economy | 43 | 52 | 48 |

| Cree Canadians | Alberta province | Canada | Market economy | 26 | 28 | 13 |

| Tuvans | Tyva Republic | Russia | Pastoralism, wages | 30 | 30 | 18 |

| Kadazan-Dusun | Sabah region | Malaysia | Pastoralism, agriculture | 25 | 26 | 18 |

| Fijian villagers | Cakaudrove province | Fiji | Foraging, agriculture, wages | 9 | 10 | 5 |

| Shuar | Morona Santiago province | Ecuador | Horticulture, hunting, foraging, recent small-scale agropastoralism | 30 | 31 | 19 |

| Miskitu | Región Autónoma del Atlántico Sur | Nicaragua | Horticulture, fishing, hunting | 13 | 17 | 15 |

| Tchimba | Kunene region | Namibia | Pastoralism | 35 | 27 | 20 |

| Aka | Southwest Central African Republic | Central African Republic | Foraging | 25 | 25 | 11 |

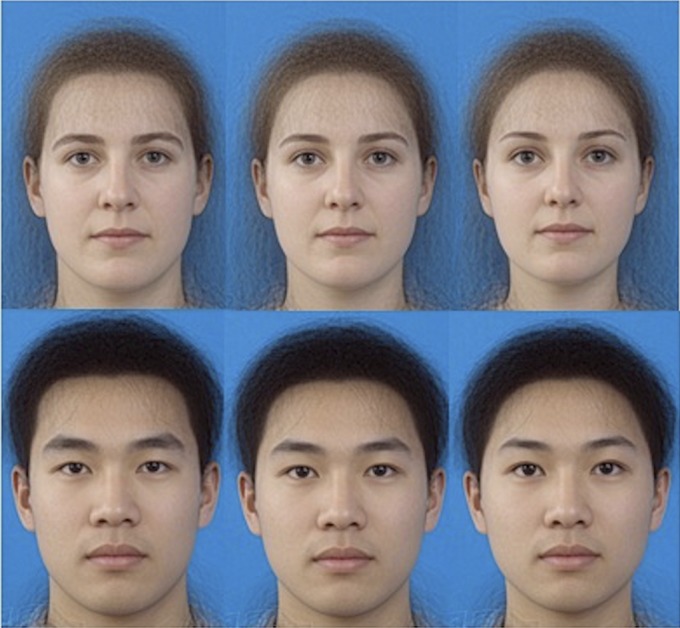

Participants were asked to choose the most attractive face from five sets (representing five different ethnicities, representing considerable phenotypic variation in human faces) of three opposite-sex photographs, with one 60% masculinized [i.e., with the shape differences between male and female faces caricatured by 60% (4)], one 60% feminized, and one unaltered face in each set (Fig. 1). Participants assessed attractiveness for long-term and short-term relationships. Participants were also asked to choose the most aggressive-looking face, and responses were scored in the same way. Custom randomization tests were used to test for nonrandomness of choice (e.g., Fig. S1), and ordinal generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were used to test for associations between choices and predictor variables.

Fig. 1.

Examples of stimuli used. A European female composite (Upper) and an East Asian male composite (Lower) are shown. Masculinized stimuli (Left) and feminized stimuli (Right) are shown.

Although the previous literature suggests that familiarity effects of ethnicity can subtly affect dimorphism preferences, this influence is small and inconsistent across cultures and is unlikely to bias results as a result of exposure to ethnic variation in facial appearance (4, 15).

Results

Men’s Preferences for Female Faces.

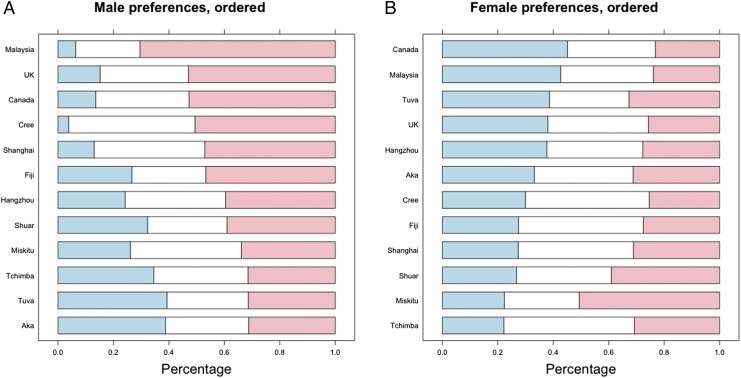

There were no significant preferences among the Aka, Shuar, or Tchimba (randomization tests, all P ≥ 0.08) or relationship context effects on choice [likelihood ratio (LR) tests, all P > 0.466], but all other groups showed nonrandom preferences (Fig. 2). Randomization tests revealed an average male preference for feminized female faces among the Canadian, Fijian, Hangzhouvian, Kadazan, Shanghainese, Cree, and UK populations (all P < 0.0003). Cree respondents expressed a stronger (P < 0.0006) preference for femininity in the short-term vs. long-term relationship context. Miskitu and Tuvans preferred feminized faces for long-term relationships (P < 0.004 and P < 0.001, respectively) and masculinized faces for short-term relationships (P < 0.034 and P < 0.001, respectively).

Fig. 2.

(A) Preferences for sex dimorphism in female faces, by group. Blue sections indicate the proportion of a group that chose masculinized faces as most attractive, white sections indicate the proportion that chose neutral faces, and pink sections indicate the proportion that chose feminized faces. (B) Preferences for sex dimorphism in male faces, by group. Blue sections indicate the proportion of a group that chose masculinized faces as most attractive, white sections indicate the proportion that chose neutral faces, and pink sections indicate the proportion that chose feminized faces.

The HDI was a significant positive predictor of preferences in both long-term and short-term relationship contexts, with a significantly stronger effect for short-term relationships (context * HDI interaction: LR test = 13.94, df = 1, P = 0.0002; long-term: slope = 1.58, z = 2.08, P = 0.038; short-term: slope = 2.68, z = 2.42, P = 0.016), indicating that men in high-HDI environments had stronger preferences for feminine women.

To explore which aspects of development may underlie this relationship, models with disease burden, fertility rate, and urbanization, alone or in combination, were fitted. For both long-term and short-term relationships, only urbanization was retained as a significant predictor of preferences (long-term: slope = 0.020, z = 2.72, P = 0.007; short-term: slope = 0.025, z = 2.00, P = 0.045). These data indicate that preferences for facially feminine women are present in highly and moderately developed urban environments but are largely absent from the small-scale groups tested here.

Women’s Preferences for Male Faces.

In male faces, women showed evidence of nonrandom preferences in all groups (Fig. 2). Randomization tests revealed significant female preferences for masculinized male faces across both relationship contexts for the Canadian, Hangzhou, and Kadazan samples (P < 0.00001, P = 0.017, and P = 0.0009, respectively); a significant preference for neutral faces among Cree, Fijians, Shanghainese, and Tchimba participants (P < 0.00002, P = 0.047, P = 0.002, and P < 0.00001, respectively); and a significant preference for femininity among the Miskitu and Shuar (P = 0.00002 and P = 0.038, respectively). There were also significant differences between groups in the effect of relationship context on preference (group * context interaction: LR test = 48.285, df = 11, P = 1.27 × 10−6). For UK participants, there was a significant preference for neutral faces in long-term relationships (P < 0.00001) and for masculinity in the short-term context (P < 0.00001). Aka and Tuvans showed a preference for masculinized faces in short-term relationships (P = 0.005 and P < 0.00001, respectively) and for feminized faces in long-term relationships (P = 0.017 and P = 0.0003, respectively). For the Kadazans and Canadians, there were significantly stronger (P = 0.002 and P = 0.00032, respectively) masculinity preferences for the short-term vs. long-term relationship context. Responses from contraceptive pill users, pregnant women, and women over 40 y of age were excluded from the analysis [changes to group n (sample size specific to each ethnic group) are provided in Table 1], because these variables have been proposed to influence masculinity preferences (33, 42) (including these participants had no qualitative effect on the reported findings).

Ordinal GLMMs indicated that, contrary to our predictions, the HDI was positively associated with preferences for masculinity in the long-term relationship context (z = 2.08, P = 0.038). There was much higher variability, and no significant relationship, in the short-term context (z = 1.435, P = 0.151), although long-term and short-term slopes were not significantly different (context * HDI interaction: LR test = 0.751, df = 1, P = 0.386).

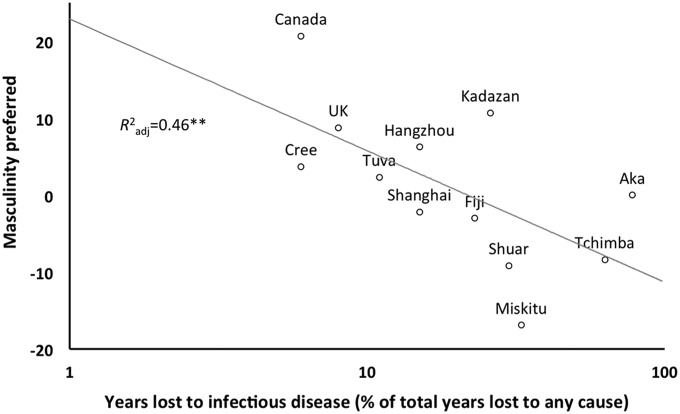

To investigate this relationship further, ordinal GLMMs were fitted with years of life lost to disease (log-transformed), local homicide rates, and urbanization level, plus all possible interactions, as potential independent variables. The only significant predictor, and the best-supported model based on the Akaike information criterion, was years lost to disease (slope = −0.211, z = 2.286, P = 0.022; Fig. 3); populations with higher disease burden were less likely to prefer masculine faces. This finding in particular, that masculinity preferences are negatively related to disease burden, directly contradicts the predictions of the immunocompetence hypothesis, as well as findings from prior research using cross-cultural samples collected online (19).

Fig. 3.

Preferences for sex dimorphism in male faces by level of disease burden. Female preferences for masculinity in male faces by group, expressed as an average [participants’ choices for most attractive male faces were recorded as +60 (feminine), 0 (average), or −60 (masculine)], plotted against years lost to infectious disease in local populations (log-transformed). Preferences for masculinity decrease as the disease burden increases.

Furthermore, we found no effects of menstrual cycle-related conception probability on masculinity preferences, adding to an ongoing debate in the field (43, 44). These findings cast further doubt on immunocompetence explanations (additional details are provided in SI Results; also see Table S3 and Fig. S2).

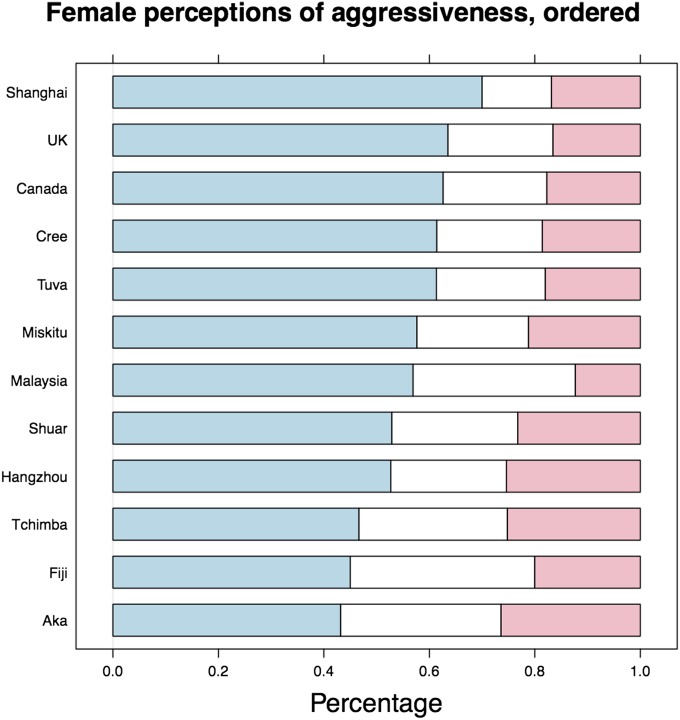

Attributions of Aggression.

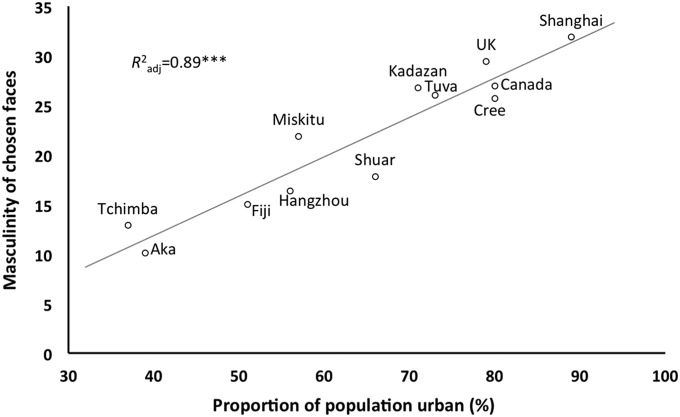

As predicted, there was a significant cross-cultural tendency for females to associate masculinity with aggression. All groups chose masculine male faces as “least prosocial/most aggressive” (randomization tests, all P < 0.004; Fig. 4). Again, an ordinal GLMM showed that the strength of this trait attribution was positively associated with the HDI (slope = 1.25, z = 4.392, P < 0.0001). However, ordinal GLMMs fitting homicide rate, disease burden, gross domestic product, and urbanization as potential independent variables demonstrated that urbanization was the best, and an extremely tight, predictor of the strength of the relationship between masculinity and the perceptions of aggressiveness (slope = 0.018, z = 6.284, P < 0.00001; Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Male faces perceived as most aggressive-looking, by group. Blue sections indicate the proportion of a group that chose masculinized faces as most aggressive, white sections indicate the proportion that chose neutral faces, and pink sections indicate the proportion that chose feminized faces.

Fig. 5.

Masculinity of male faces perceived as most aggressive-looking, by level of urbanization. Average levels of masculinity in the male faces chosen as most aggressive-looking by group, plotted against level of urbanization, are shown. Participants in urban environments were more likely to choose masculine faces when asked to choose the most aggressive-looking face.

Similar results were found for female faces (SI Results and Figs. S3, S4, and S5).

Controlling for Cultural Nonindependence.

A potential explanation for the observed relationships between environmental variables and preferences in our data are that these traits are transmitted between cultural groups (the problem of nonindependence of cultures). This transmission can occur when groups have shared cultural ancestry or engage in cultural borrowing and sharing. To explore this possibility, it was necessary to use a different analysis approach and an alternate method of summarizing preference data. Participants’ choices for the most attractive female faces were recorded as +60 (feminine), 0 (average), or −60 (masculine), whereas for male faces, responses were recorded as +60 (masculine), 0 (average), or −60 (feminine). Responses were averaged across long-term and short-term relationships and all faces to create a general preference score for each participant. Culturally “lagged” variables were created and entered into regressions as control variables (details are provided in SI Results). These analyses provided no evidence of a relationship between groups’ preferences and the preferences of culturally similar groups (all P > 0.05), and all significant environmental predictors remained significant after controlling for the effects of cultural proximity (SI Results). These analyses suggest that preferences and personality attributions are organized primarily by environmental variables, such as development and urbanization, rather than by cultural interchange or shared ancestry.

Discussion

In summary, preferences for dimorphism, and perceptions that masculinity signals aggressiveness, are stronger in large-scale, urban societies and in groups that have low disease, fertility, and homicide rates. These results do not simply reflect poor task performance in lower development environments, because directional preferences are present in several such populations. Notably, women’s preferences for masculinity are actually reversed, and not simply attenuated in several of the small-scale groups. We also note that the trait attribution data are more consistent across cultures than the preference data (perceptions of masculinity as “nasty” are statistically significant in each group). Although familiarity with printed images may account for some variance in our results, our data indicate that observers are making meaningful (i.e., nonrandom), but culturally variable, judgments of the stimuli. Our sample of 12 cultures is far from exhaustive, and further research will help clarify the generalizability of these results; nevertheless, the findings are hard to reconcile with theories that facial dimorphism was an ancestral cue of mate value. Some recent authors have expressed doubt about immunocompetence hypotheses of dimorphism preferences, on the basis of theoretical considerations (29, 34), and our findings provide empirical validation for these concerns.

However, our data show that the distribution of dimorphism preferences is nonrandom across cultures, and this observation requires explanation. In a cross-cultural study of this nature, it is impossible to determine the causal factors underlying the pattern of data, which may reflect environmental or ethnographic differences that we have not considered. Nonetheless, the urbanization data, in particular, lead us to speculate (parsimoniously) that the “visual diet” of the observers may be an important factor in determining trait attributions and preferences. Prior research shows that preferences are influenced by visual exposure and calibrated to local morphological norms (38). If facial dimorphism were greater in high-HDI environments, women from such environments might be predicted to prefer more masculine faces than women from low-HDI environments. This possibility is plausible, because men in Western industrialized contexts may have higher testosterone levels than men in small-scale societies, likely reflecting a reduction in energetic stressors, such as food shortage and disease (45), and sexual dimorphism in body size is also greater in these environments (46).

Visual diet may also play a role in shaping perceptions of the link between dimorphism and personality. Our findings indicate that masculine facial appearance is cross-culturally perceived to be associated with aggression but that the strength of these attributions is closely associated with indices of development, particularly urbanization. In high-HDI environments, countless unfamiliar conspecifics are encountered, and heuristics, such as rapid stereotypical trait attribution, might be useful to cope with the ensuing volume of social information (47). In contrast, in small-scale societies, personality attributions could more typically be made on the basis of verifiable information obtained through direct personal experiences or via reputational information.

Our findings raise the possibility that many recent reports of trait attribution in the face perception literature [e.g., rapid, stereotypical trait attributions made to faces (48)], and the apparent importance of such judgments in predicting the outcome of important decisions [e.g., electoral contests (49)], reflect information-processing strategies acquired as the result of historically recent social environments, possibly indicating an ontogenetic effect of extensive experience with unfamiliar faces in urban/modern Western environments.

Nonetheless, the stereotypes used in urbanized environments may have a kernel of truth: the evidence that masculinity is a correlate of aggressiveness, for example, is reasonably strong (22). The increased differentiation of social roles in high-HDI environments could affect the signal value of masculinity. If more prestigious social roles are occupied by more masculine individuals, masculinity may act as a more reliable indicator of prestige in high-HDI environments than in low-HDI environments, and hence be viewed as attractive. Further work is required to determine if the relationship between appearance and prestige is stronger (or weaker) in high-HDI rather than low-HDI environments. It may also be the case that femininity is a better correlate of reproductive potential, or some other aspect of mate value, in high-HDI environments than it is in low-HDI environments. Such facial attributions may therefore reflect functional processes, even if they have not played an important role in human societies until recently, when the large datasets required to recognize these weak associations have been offered by exposure to large numbers of conspecifics.

Materials and Methods

Stimuli consisted of sets of facial photographs, one set for each of five ethnic groups (European, East Asian, South Asian, African Caribbean, and South American). For each ethnic group, composite photographs were generated using morphing software (Psychomorph) to average same-sex photographs for each of the five groups. Feature points were delineated on the male and female composites and used to define a vector describing the average male and female facial morphology. This information was used to transform the 10 composites in either a masculine or feminine direction along the male–female axis, following previous methods (4). European, East Asian, and South Asian composites used were those composites constructed by Stephan et al. (50). Details of the African Caribbean composite can be found in a study by Penton-Voak et al. (15). The South American composites were constructed from 24 females and 24 males of the Matsigenka (Peru). The resulting 10 sets of stimuli each consisted of three same-sex, same-ethnicity composite photographs: the original composite, a 60% feminized composite, and a 60% masculinized composite (Fig. 1).

Participants (n = 962) were from 12 different populations with widely varying socioecologies (Table 1 and Tables S1 and S2). Participants took part on a voluntary basis. Each participant was presented with a set of three opposite-sex photographs and asked to choose the one that he or she found most attractive for a long-term relationship. After choosing a face, the same question was repeated using faces from each of the remaining four ethnic groups, one after another. The process was then repeated with judgments about attractiveness for a short-term relationship and for perceptions of personality and other traits not reported here (SI Materials and Methods). Participants from Canada, the United Kingdom, and Hangzhou (China) took part in a self-administered computer presentation, whereas participants from the remaining groups were presented with laminated cards by a researcher. Prior research suggests that these methods produce similar results (15).

For all questions, a brief exposition of what exactly was meant by the question was given as follows:

-

i)

Which face is most attractive in a long-term context (which face looks like it would make the best long-term partner, meaning, among other things, marriage)?

-

ii)

Which face is most attractive in a short-term context (short-term means attractive for things like dating or a sexual relationship but without prospects for the long term)?

-

iii)

Which face is the nastiest (most cruel, unkind, aggressive, difficult, unpleasant to live with)?

After completing the experiment, a participant information questionnaire was administered in which additional questions were asked regarding social, demographic, health, and economic factors.

For each ethnic group of face and relationship context, participants faced a trinary choice between three faces (masculinized, neutral, and feminized). To test for nonrandomness of choice (irrespective of direction), we used randomization tests written in R version 2.15.1. For each trinary choice, n (sample size specific to each ethnic group) simulated subjects picked one with a probability of one-third; this process was repeated five (single-relationship context, long-relationship context, or short-relationship context) or 10 (both contexts together) times, representing the choices of each subject over the five ethnic face types. The mean proportion of choices for masculinized, neutral, and feminized faces was calculated and represented as a locus in a ternary diagram. The vector from the centroid (equal choices to the three categories) was calculated as the measure of the direction and magnitude of preference. This procedure was replicated 100,000 times to give a distribution of vectors under random choice using Monte Carlo randomization methods (51). The proportion of vectors exceeding the magnitude of the observed vector for a class of choosers (e.g., Canadians in the short-term relationship context and Tuvans in both contexts according to the question) represents the P value for that class of choosers under the null hypothesis (a graphical demonstration is shown in Fig. S1).

To test for associations between choices and predictor variables, ordinal GLMMs (52) were fitted using the ordinal package in R (53), with participant identification and population of the chooser as random effects. This approach is an extension of logistic regression to account for the fact that, rather than two choices (e.g., masculinized vs. feminized), there is a trinary choice, with the three choices representing an ordered sequence from masculinized through neutral to feminized. Being mixed models, they also account for the nonindependence of experimental participants’ choices, given that each participant scored several faces (i.e., from different ethnic groups). This feature captures both the repeated-measures nature of each participant’s choices and the hierarchical structure of the data (participants nested within ethnic group and predictors only applicable at the latter level). Ordinal GLMMs were considered the most appropriate, and conservative, approach because we could not assume that preferences across masculinized, neutral, and feminized faces would be linear. The convergence of models was assessed by inspecting the maximum absolute gradient of the log-likelihood function and the magnitude of the Hessian (53). We note that analysis of the mean preference scores with weighted ordinary least squares regression (less appropriate to the data but not reliant on iterative model fitting) yields very similar results in pattern and statistical significance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Justin Park and Martin Tovée for helpful comments on the manuscript and Thomas Pollett for helpful discussion about statistical analyses. This research was funded by a Leverhulme Trust grant (to I.S.P.-V.). I.M.S. was supported by a University of Bristol studentship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1409643111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ryan MJ, Keddy-Hector A. Directional patterns of female mate choice and the role of sensory biases. Am Nat. 1992;139(S1):S4–S35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folstad I, Karter AJ. Parasites, bright males, and the immunocompetence handicap. Am Nat. 1992;139(3):603–622. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnstone RA. Sexual selection, honest advertisement and the handicap principle: Reviewing the evidence. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 1995;70(1):1–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1995.tb01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrett DI, et al. Effects of sexual dimorphism on facial attractiveness. Nature. 1998;394(6696):884–887. doi: 10.1038/29772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston VS. Female facial beauty: The fertility hypothesis. Pragmatics & Cognition. 2000;8(1):107–122. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Symons D. Beauty is in the adaptations of the beholder: The evolutionary psychology of human female sexual attractiveness. In: Abramson PR, Pinkerton SD, editors. Sexual Nature/Sexual Culture. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press; 1995. pp. 80–118. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones D, Hill K. Criteria of facial attractiveness in five populations. Hum Nat. 1993;4(3):271–296. doi: 10.1007/BF02692202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston VS, Franklin M. Is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Ethol Sociobiol. 1993;14(3):183–199. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham MR, Roberts AR, Wu CH, Barbee AP, Druen PB. “Their ideas of beauty are, on the whole, the same as ours”: Consistency and variability in the cross-cultural perception of female physical attractiveness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;68(2):261–279. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith MJ, et al. Facial appearance is a cue to oestrogen levels in women. Proc Biol Sci. 2006;273(1583):135–140. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roumen FJME, Doesburg WH, Rolland R. Hormonal patterns in infertile women with a deficient postcoital test. Fertil Steril. 1982;38(1):42–47. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)46394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peccei JS. Menopause: Adaptation or epiphenomenon? Evol Anthropol. 2001;10(2):43–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore FR, Law Smith MJ, Taylor V, Perrett DI. Sexual dimorphism in the female face is a cue to health and social status but not age. Pers Individ Dif. 2011;50(7):1068–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes G. The evolutionary psychology of facial beauty. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57(1):199–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penton-Voak IS, Jacobson A, Trivers R. Populational differences in attractiveness judgements of male and female faces: Comparing British and Jamaican samples. Evol Hum Behav. 2004;25(6):355–370. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones D. Sexual selection, physical attractiveness, and facial neoteny: Cross-cultural evidence and implications. Curr Anthropol. 1995;36(5):723–748. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott IML, Swami V, Josephson SC, Penton-Voak IS. Context-dependent preferences for facial dimorphism in a rural Malaysian population. Evol Hum Behav. 2008;29(4):289–296. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barber N. The evolutionary psychology of physical attractiveness: Sexual selection and human morphology. Ethol Sociobiol. 1995;16(5):395–424. [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeBruine LM, Jones BC, Crawford JR, Welling LLM, Little AC. The health of a nation predicts their mate preferences: Cross-cultural variation in women’s preferences for masculinized male faces. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;277(1692):2405–2410. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thornhill R, Gangestad SW. Facial sexual dimorphism, developmental stability, and susceptibility to disease in men and women. Evol Hum Behav. 2006;27(2):131–144. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Little AC, Jones BC, Penton-Voak IS, Burt DM, Perrett DI. Partnership status and the temporal context of relationships influence human female preferences for sexual dimorphism in male face shape. Proc Biol Sci. 2002;269(1496):1095–1100. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott IML, Clark AP, Boothroyd LG, Penton-Voak IS. Do men’s faces really signal heritable immunocompetence? Behav Ecol. 2013;24(3):579–589. doi: 10.1093/beheco/ars092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks R, et al. National income inequality predicts women’s preferences for masculinized faces better than health does. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;278(1707):810–812. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts ML, Buchanan KL, Evans MR. Testing the immunocompetence handicap hypothesis: A review of the evidence. Anim Behav. 2004;68(2):227–239. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pound N, Penton-Voak IS, Surridge AK. Testosterone responses to competition in men are related to facial masculinity. Proc Biol Sci. 2009;276(1654):153–159. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tybur JM, Gangestad SW. Mate preferences and infectious disease: Theoretical considerations and evidence in humans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366(1583):3375–3388. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehta PH, Beer J. Neural mechanisms of the testosterone-aggression relation: The role of orbitofrontal cortex. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010;22(10):2357–2368. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Archer J. Testosterone and human aggression: An evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30(3):319–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puts DA. Beauty and the beast: Mechanisms of sexual selection in humans. Evol Hum Behav. 2010;31(3):157–175. [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeBruine LM, Jones BC, Little AC, Crawford JR, Welling LLM. Further evidence for regional variation in women’s masculinity preferences. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;278(1707):813–814. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penton-Voak IS, et al. Menstrual cycle alters face preference. Nature. 1999;399(6738):741–742. doi: 10.1038/21557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Little AC, Connely J, Feinberg DR, Jones BC, Roberts SC. Human preference for masculinity differs according to context in faces, bodies, voices, and smell. Behav Ecol. 2011;22(4):862–868. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones BC, et al. Effects of menstrual cycle phase on face preferences. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37(1):78–84. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9268-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu DW, Proulx SR, Shepard GH. In: Masculinity, culture and the Paradox of the Lek. Body Beautiful: Evolutionary and Sociocultural Perspectives. Furnham A, Swami V, editors. Palgrave Macmillan; Basingstoke, UK: 2007. pp. 88–107. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav Brain Sci. 2010;33(2-3):61–83, discussion 83–135. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu DW, Shepard GH., Jr Is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Nature. 1998;396(6709):321–322. doi: 10.1038/24512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones BC, DeBruine LM, Little AC. Adaptation reinforces preferences for correlates of attractive facial cues. Vis Cogn. 2008;16(7):849–858. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Little AC, Jones BC, DeBruine LM. Facial attractiveness: Evolutionary based research. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366(1571):1638–1659. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Batres C, Perrett DI. The influence of the digital divide on face preferences in El Salvador: People without internet access prefer more feminine men, more masculine women, and women with higher adiposity. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e100966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wood W, Eagly AH. A cross-cultural analysis of the behavior of women and men: Implications for the origins of sex differences. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(5):699–727. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wood W, Eagly AH. 2012. Biosocial Construction of Sex Differences and Similarities in Behavior, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, eds Zanna MP, Olson JM, (Academic, San Diego), pp 55–123.

- 42.Little AC, et al. Women’s preferences for masculinity in male faces are highest during reproductive age range and lower around puberty and post-menopause. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(6):912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wood W, Kressel L, Joshi P, Louie B. Meta-analysis of menstrual cycle effects on women’s mate preferences. Emot Rev. 2014;6(3):229–249. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gildersleeve K, Haselton MG, Fales MR. Do women’s mate preferences change across the ovulatory cycle? A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(5):1205–1259. doi: 10.1037/a0035438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bribiescas RG. Testosterone levels among Aché hunter-gatherer men: A functional interpretation of population variation among adult males. Hum Nat. 1996;7(2):163–188. doi: 10.1007/BF02692109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anton SC, Snodgrass JJ. Origins and evolution of genus Homo: A new perspective. Curr Anthropol. 2012;53(S6):S479–S496. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macrae CN, Milne AB, Bodenhausen GV. Stereotypes as energy-saving devices: A peek inside the cognitive toolbox. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;66(1):37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willis J, Todorov A. First impressions: Making up your mind after a 100-ms exposure to a face. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(7):592–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Todorov A, Mandisodza AN, Goren A, Hall CC. Inferences of competence from faces predict election outcomes. Science. 2005;308(5728):1623–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.1110589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stephan CN, et al. Two-dimensional computer-generated average human face morphology and facial approximation. In: Clement JG, Marks MK, editors. Computer Graphic Facial Reconstruction. Elsevier Science; Burlington, VT: 2005. pp. 105–127. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robert CP, Casella G. Introducing Monte Carlo Methods with R. Springer; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. 2nd Ed Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Christensen RHB. 2011 Analysis of ordinal data with cumulative link models—estimation with the R-package ‘ordinal’. Available at http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ordinal/vignettes/clm_intro.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.