Abstract

Hydrogen fluoride (HF) and selected nonbasic and weakly coordinating (toward cationic metal) hydrogen-bond acceptors (e.g., DMPU) can form stable complexes through hydrogen bonding. The DMPU/HF complex is a new nucleophilic fluorination reagent that has high acidity and is compatible with cationic metal catalysts. The gold-catalyzed mono- and dihydrofluorination of alkynes using the DMPU/HF complex yields synthetically important fluoroalkenes and gem-difluoromethlylene compounds regioselectively.

Despite its usefulness, the incorporation of fluorine into organic molecules remains a synthetic challenge.1 Fluorination reagents can be classified as electrophilic or nucleophilic. Nucleophilic fluorination reagents are usually less expensive than their electrophilic counterparts (e.g., Selectfluor, NFSI). Most, if not all, fluorinating reagents (electrophilic or nucleophilic) are made from hydrogen fluoride (HF). Thus, an HF-based reagent would be ideal in terms of cost and atom economy, but HF itself is a hazardous gas at room temperature and is very difficult to handle. Complexes of HF with organic bases such as Olah’s reagent (pyridine/HF complex)2 and triethylamine/HF complex3 are liquids at room temperature, so they are easier to handle. Pyridine/HF and triethylamine/HF have been explored extensively as nucleophilic sources of fluorine,2a but these organic bases are not without problems: they reduce the acidity of the system and may interfere with many metal catalysts. For example, pyridine can complex strongly with many transition metals and therefore reduce their activities.

We propose that HF and selected nonbasic, non-nucleophilic, and weakly coordinating (toward cationic metal) hydrogen-bond acceptors can form stable complexes through hydrogen bonding. These HF complexes can act as new nucleophilic fluorination reagents. In 2009, Laurence and co-workers reported a comprehensive database of hydrogen-bond basicity (measured by pKBHX).4 For most compounds, pKBHX is in the range of 1 to 5, where a bigger number indicates higher hydrogen-bond basicity.4 We used this database as a guideline to select an ideal hydrogen-bond acceptor. Among many hydrogen-bond acceptors in Laurence’s database, we considered 1,3-dimethyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2(1H)-pyrimidinone (DMPU) as an ideal hydrogen-bond acceptor to form a complex with HF. DMPU is inexpensive and readily available. Even more important, DMPU (pKBHX = 2.82) is a better hydrogen-bond acceptor than pyridine (pKBHX = 1.86) and Et3N (pKBHX = 1.98)4 and at same time is much less basic than pyridine and Et3N (Figure 1). Thus, the DMPU/HF complex should have higher acidity than the pyridine/HF and triethylamine/HF complexes. Also, DMPU is weakly coordinating to most metal catalysts, so it is unlikely to interfere strongly with most transition-metal catalysts. Moreover, DMPU is a very weak nucleophile, so it will not compete with HF in nucleophilic reactions. Therefore, the HF/DMPU complex should be an ideal fluorination reagent,5 especially in transition-metal-catalyzed reactions.6 Herein we are glad to report a proof of concept application of the DMPU/HF complex in the gold-catalyzed, highly regioselective mono- and dihydrofluorination of alkynes.

Figure 1.

Comparison of DMPU/HF with pyridine/HF and Et3N/HF.

Fluoroalkenes are important synthetic building blocks and targets,7 but they are made from a shallow pool of fluoroalkene synthons8 or their preparation requires lengthy procedures that are not functional-group-friendly.9 Typical synthetic methods of fluoroalkenes include tandem addition–reduction,9a tandem addition–elimination,10 Shapiro reaction,7b Julia–Kocienski olefination,11 and Peterson olefination.12 Sadighi and co-workers have reported a SIPr–Au catalyzed monohydrofluorination of alkynes using Et3N/HF,13 but because of the low acidity of the Et3N/HF system, stoichiometric amounts of acid and acidic cocatalyst have to be used. Also, this method works only for internal alkynes, where there is no reliable way to control the regioselectivity. By taking advantage of the unique properties of our DMPU/HF reagent, we were able to mono- and dihydrofluorinate both terminal and internal alkynes in a highly regioselective fashion.

We used the monohydrofluorination of alkyne 1a as our model reaction. The fluorination agents alone were not able to fluorinate 1a (Table 1, entries 1–3), and a strong acid (TfOH) was not an effective mediator either (entries 4–5). The HF/DMPU complex we prepared contains 65 wt % HF, corresponding to an HF:DMPU molar ratio of around 11.8:1.14 We recently reported acid-assisted activation of an imidogold precatalyst as a superior way to generate cationic gold compared with the common silver-based methodology.15 We found that our DMPU/HF system is acidic enough to activate the imidogold precatalyst (Au-1). Indeed, the DMPU/HF system is much more efficient in the fluorination of 1a than the commonly used pyridine/HF complex (entries 6 and 7). The DMPU/HF/Au-1 system is highly reactive but it gave a mixture of monofluorinated product 2a and difluorinated product 3a (entry 8). We were able to achieve selective monofluorination by reducing the amount of fluorination reagent from 3 to 1.2 equiv (entry 9), and the good yield and selectivity of product 2a were maintained even at lower gold precatalyst loadings of 2% and 1% (entries 10 and 11).

Table 1. Optimization of the Reaction Conditions for Monohydrofluorination of Alkynesa.

| entry | HF sourcea | catalyst | t (h) | 2a (%)b | 3a (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pyridine/HF | – | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Bu4N+OTf–/HF | – | 48 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | DMPU/HF | – | 48 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | pyridine/HF | TfOH (100%) | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | DMPU/HF | TfOH (100%) | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | pyridine/HF | Au-1 (5%) | 5 | 13 | 3 |

| 7 | DMPU/HF | Au-1 (5%) | 5 | 48 | 52 |

| 8 | DMPU/HF | Au-1 (5%) | 24 | 32 | 68 |

| 9 | DMPU/HF (1.2 equiv) | Au-1 (5%) | 3 | 99 | <1 |

| 10 | DMPU/HF (1.2 equiv) | Au-1 (2%) | 3 | 99 | <1 |

| 11 | DMPU/HF (1.2 equiv) | Au-1 (1%) | 5 | 83 | 0 |

Concentrations of HF sources: pyridine/HF (70%), DMPU/HF (65% w/w).

Determined by GC–MS.

With the optimized conditions in hand, we investigated the scope of the monohydrofluorination of alkynes (Table 2). Clean and regioselective transformations were observed for all of the terminal alkynes tested (Table 2, entries 1–8). The reaction also worked well for internal alkynes, although longer reaction times and higher loadings of gold catalyst were needed (entries 9–11). This reaction also has good functional group tolerance: an alkyne with a strong electron-withdrawing group (entry 9) and an alkyne with an acidic C–H group and an ester group (entry 12) gave the corresponding fluoroalkenes in good yields and selectivity.

Table 2. Substrate Scope for Monohydrofluorination of Alkynes 1a.

Conditions: Alkyne 1 (0.5 mmol) and DMPU/HF (65 wt %, 1.2 equiv) in DCE at 55 °C for 3 h.

Isolated yields (other yields are 19F NMR yields).

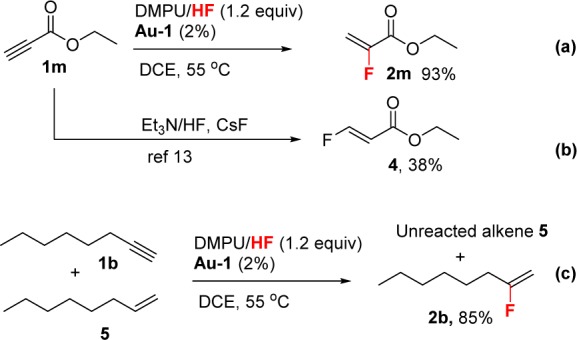

We found that in the monohydrofluorination of acceptor-substituted terminal alkyne 1m, the DMPU/HF/Au-1 system yielded a completely different regioisomer compared with the literature report, where no catalyst was used. Thus, the uncatalyzed addition of HF to 1m gave the Michael addition product 4 (Scheme 1b),16 whereas our DMPU/HF/Au-1 system reversed the tendency toward Michael addition to give 2m instead as the only isomer (Scheme 1a).

Scheme 1. Selectivity of the DMPU/HF/Au-1 Fluorination System.

The DMPU/HF/Au-1 system is highly effective for alkyne hydrofluorination, but it is not a good catalyst for hydrofluorination of alkenes (Scheme 1c). In other words, alkene groups are well-tolerated. For example, a 1:1 mixture of 1-octene (5) and 1-octyne (1b) gave only alkyne hydrofluorination product 2b under the conditions of our model reaction.

gem-Difluoromethylene (CF2)-containing compounds are important building blocks and targets in organic synthesis.7a,17 In this regard, dihydrofluorination of an alkyne is a straightforward and atom-economical way to synthesize CF2-containing compounds 3. Olah and co-workers reported a synthesis of difluorinated alkanes with limited scope and selectivity.2b As shown above (Table 1, entry 8), we observed the formation of 3a during our search for optimal conditions for the synthesis of 2a. We believed that further hydrofluorination of fluoroalkenes 2 would give the dihydrofluorination products 3, but as we saw in Scheme 1c, our DMPU/HF/Au-1 system is not a good catalytic system for the hydrofluorination of alkenes, so complete conversion of 2 to 3 is difficult. We then explored the possibility of using a cocatalyst or additive that could catalyze the further hydrofluorination of 2 to give the desired product 3 (Table 3). Additional nucleophilic fluorine sources (CsF and AgF; entries 1 and 2) were moderately effective, but could not convert all of the 2a to 3a. The weak Lewis acid KCTf3 (entry 3) was not effective either, but the stronger acids Ga(OTf)3 and KHSO4 (entries 4–5) helped to produce 3a with very good selectivity. Because KHSO4 is relatively inexpensive and readily available, we selected KHSO4 as our cocatalyst for the synthesis of 3.

Table 3. Optimization of the Conditions for Dihydrofluorination of Alkynes 1.

| entry | additive | t (h) | 2a (%) | 3a (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CsF (100%) | 24 | 15 | 85 |

| 2 | AgF (100%) | 24 | 96 | 4 |

| 3 | KCTf3 (10%) | 24 | 67 | 33 |

| 4 | Ga(OTf)3 (10%) | 24 | <0.5 | 99 |

| 5 | KHSO4 (150%) | 24 | <1 | 99 |

To get a clearer understanding of the role of a Lewis acid like Ga(OTf)3 in the formation of gem-difluoromethylene compounds 3 we conducted a control experiment (eq 1). DMPU/HF alone can convert 2a to 3a without any catalyst, but this reaction is sluggish (eq 1, condition 1). However, a Lewis acid like Ga(OTf)3 can significantly speed up this conversion (eq 1, condition 2).

|

1 |

With the optimized conditions for dihydrofluorination of alkynes in hand, we investigated the substrate scope of this transformation (Table 4). This reaction worked very well for both terminal and internal alkynes.

Table 4. Substrate Scope for Dihydrofluorination of Alkynes 1a.

Alkyne 1 (0.5 mmol), DMPU/HF (65 wt %, 3.0 equiv), and KHSO4 (1.5 equiv) in DCE at 55 °C for 12 h.

Isolated yield (other yields are 19F NMR yields).

The usefulness of our method was further validated by the synthesis of fluorocarbocycles via ring-closing metathesis (RCM) reactions (Scheme 2).8 Because fluoroalkenes can be prepared efficiently using our new method and alkene groups are well-tolerated, we can envision a diverse set of fluorocycles made by the combination of alkyne monohydrofluorination and RCM reactions.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Fluorocarbocycles.

In summary, our new fluorination reagent DMPU/HF not only is easily handled but also is an efficient fluorination system for the regioselective mono- and dihydrofluorination of alkynes. Further applications of this new fluorination reagent as well as commercialization discussions are currently being conducted in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health (R15 GM101604-01) for financial support. O.E.O. is grateful to the University of Louisville for a McSweeney Diversity Endowed Fellowship.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures and copies of spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- a Chambers R. D.Fluorine in Organic Chemistry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2004. [Google Scholar]; b Hiyama T.Organofluorine Compounds: Chemistry and Applications; Springer: Berlin, 2000. [Google Scholar]; c Kirsch P.Modern Fluoroorganic Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]; d Muller K.; Faeh C.; Diederich F. Science 2007, 317, 1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Schlosser M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Fluorine-Containing Synthons; Soloshonok V. A., Ed.; ACS Symposium Series, Vol. 911; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 2005. [Google Scholar]; g Uneyama K.Organofluorine Chemistry; Blackwell: Oxford, U.K., 2006. [Google Scholar]

- a Yoneda N. Tetrahedron 1991, 47, 5329. [Google Scholar]; b Olah G. A.; Welch J. T.; Vankar Y. D.; Nojima M.; Kerekes I.; Olah J. A. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 3872. [Google Scholar]

- Haufe G. J. Prakt. Chem./Chem.-Ztg. 1996, 338, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Laurence C.; Brameld K. A.; Graton J.; Le Questel J.-Y.; Renault E. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 4073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Many HF/urea and HF/amide complexes have been used for fluorination of benzotrichlorides. See: Hayashi H.; Sonoda H.; Goto K.; Fukumura K.; Naruse J.; Oikawa H.; Nagata T.; Shimaoka T.; Yasutake T.; Umetani H.; Kitashima T. U.S. Patent 6,417,361, 2002.

- Gouverneur V. Science 2009, 325, 1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Jin Z.; Hammond G. B.; Xu B. Aldrichimica Acta 2012, 45, 67. [Google Scholar]; b Yang M.-H.; Matikonda S. S.; Altman R. A. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 3894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Patrick T. B.; Nadji S. J. Fluorine Chem. 1990, 49, 147. [Google Scholar]; d Yamaki Y.; Shigenaga A.; Tomita K.; Narumi T.; Fujii N.; Otaka A. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Watanabe D.; Koura M.; Saito A.; Yanai H.; Nakamura Y.; Okada M.; Sato A.; Taguchi T. J. Fluorine Chem. 2011, 132, 327. [Google Scholar]; f Narumi T.; Tomita K.; Inokuchi E.; Kobayashi K.; Oishi S.; Ohno H.; Fujii N. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Nakamura Y.; Okada M.; Sato A.; Horikawa H.; Koura M.; Saito A.; Taguchi T. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 5741. [Google Scholar]; h Zhang H.; Zhou C.-B.; Chen Q.-Y.; Xiao J.-C.; Hong R. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Lemonnier G.; Van Hijfte N.; Sebban M.; Poisson T.; Couve-Bonnaire S.; Pannecoucke X. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Prakash G. K. S.; Chacko S.; Vaghoo H.; Shao N.; Gurung L.; Mathew T.; Olah G. A. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Han S. Y.; Jeong I. H. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 5518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Zajc B.; Kake S. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m Burton D. J.; Yang Z.-Y.; Qiu W. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n Furuya T.; Ritter T. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 2860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o Pfund E.; Lebargy C.; Rouden J.; Lequeux T. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 7871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; p Kerr W. J.; Morrison A. J.; Pazicky M.; Weber T. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; q Nguyen T.-H.; Abarbri M.; Guilloteau D.; Mavel S.; Emond P. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3434. [Google Scholar]; r Van Steenis J. H.; Van der Gen A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 897. [Google Scholar]; s van Steenis J. H.; van der Gen A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2002, 2117. [Google Scholar]; t Ghosh A. K.; Banerjee S.; Sinha S.; Kang S. B.; Zajc B. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim S. S.; Bellingham R. K.; Satcharoen V.; Brown R. C. D. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Thi-Huu N.; Abarbri M.; Guilloteau D.; Mavel S.; Emond P. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 3434. [Google Scholar]; b La Combe E. M.; Stewart B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961, 83, 3457. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser M.; Brügger N.; Schmidt W.; Amrhein N. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 7731. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L.; Ni C.; Zhao Y.; Hu J. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 5089. [Google Scholar]

- Asakura N.; Usuki Y.; Iio H. J. Fluorine Chem. 2003, 124, 81. [Google Scholar]

- a Akana J. A.; Bhattacharyya K. X.; Mueller P.; Sadighi J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 7736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gorske B. C.; Mbofana C. T.; Miller S. J. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The boiling point of DMPU/HF complex (65 wt % HF) is not well defined (HF evaporates continuously in the range of 50–120 °C). The HF in the DMPU/HF complex also evaporates slowly in open air at 55 °C (see the Supporting Information for details).

- Han J.; Shimizu N.; Lu Z.; Amii H.; Hammond G. B.; Xu B. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick T. B.; Neumann J.; Tatro A. J. Fluorine Chem. 2011, 132, 779. [Google Scholar]

- a Urbina-Blanco C. A.; Skibinski M.; O’Hagan D.; Nolan S. P. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 7201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chen Z.; Zhu J.; Xie H.; Li S.; Wu Y.; Gong Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Liu Y.-L.; Yu J.-S.; Zhou J. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2, 194. [Google Scholar]; d Jiang H.; Lu W.; Yang K.; Ma G.; Xu M.; Li J.; Yao J.; Wan W.; Deng H.; Wu S.; Zhu S.; Hao J. Chem.—Eur. J. 2014, 20, 10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Jiang H.; Yuan S.; Cai Y.; Wan W.; Zhu S.; Hao J. J. Fluorine Chem. 2012, 133, 167. [Google Scholar]; f Liu N.; Cao S.; Shen L.; Wu J.; Yu J.; Zhang J.; Li H.; Qian X. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 1982. [Google Scholar]; g Dong X.; Zhao Y.-M.; Sun J. Synlett 2013, 24, 1221. [Google Scholar]; h Fang C.; Wu F. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 881–883196–2006. [Google Scholar]; i Yang Y.-Y.; Meng W.-D.; Qing F.-L. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Deleuze A.; Menozzi C.; Sollogoub M.; Sinaye P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 6680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Meng W.-D.; Qing F.-L. In Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology; Ojima I., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, U.K., 2009; Chapter 8, pp 201–212. [Google Scholar]; l Chatupheeraphat A.; Soorukram D.; Kuhakarn C.; Tuchinda P.; Reutrakul V.; Pakawatchai C.; Saithong S.; Pohmakotr M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 6844. [Google Scholar]; m Munemori D.; Narita K.; Nokami T.; Itoh T. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n Reddy V. P.; Perambuduru M.; Alleti R. Adv. Org. Synth. 2006, 2, 327. [Google Scholar]; o Xu B.; Mashuta M. S.; Hammond G. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.