Abstract

Environment influences brain development, neurogenesis and, possibly, vulnerability to neurodegenerative disease. We retrospectively examined the brains of aged rhesus monkeys reared during early life in either small cages or larger, “standard-sized” cages; all monkeys were subsequently maintained in standard-sized cages during adulthood. Aged monkeys reared in smaller cages exhibited significantly greater β-amyloid plaque deposition in the neocortex and a significant reduction in synaptophysin immunolabeling in cortical regions compared to aged monkeys reared in standard-sized cages (p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively). These findings suggest that early environment may influence brain structure and vulnerability to neurodegenerative changes in late life.

Keywords: Aging, β-Amyloid, Neurodegeneration, Environment, Neocortex, Rhesus monkey, Synapse density, Synaptophysin

1. Introduction

Neuronal survival (Beaulieu and Colonnier, 1989), spine density (Comery et al., 1996), and the establishment of neuronal circuitry (Fox, 1992) are influenced by experience and environment during nervous system development. Experience can also alter cortical dendrite complexity, synapse number and neural stem cell number in the adult brain (Kempermann et al., 1998; Kleim et al., 1996). Epidemiological studies suggest that environmental experience may also influence the risk of developing the most common neurodegenerative disorder, Alzheimer’s disease (Snowdon, 2003; Stern et al., 1994). For example, early life factors including education and “creative indices” have been associated with an increased prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease (Snowdon et al., 1996).

The study of non-human primates may shed light on mechanisms underlying neuronal vulnerability associated with aging and disease. Aged rhesus monkeys develop cortical β-amyloid plaques that cross-react with antibodies against amyloid filaments and their constituent proteins derived from the brains of Alzheimer’s disease subjects (Selkoe et al., 1987). The present study examined the potential influence of early environmental experience on the appearance of neurodegenerative alterations in late life in non-human primates. The brains of monkeys that had been reared under standard or atypically small housing conditions in early life were subsequently made available late in the animals’ lives to the authors of this study. We investigated and confirmed with reasonable confidence the distinct early life housing conditions of the monkeys, and then quantitatively examined β-amyloid plaque density and synaptophysin immunoreactivity in the brain. We find an association between early life experience and late life risk of exhibiting neurodegeneration.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Adult and aged rhesus monkeys were subjects of this study. In late life, when the subjects became available to study investigators, all animals were housed at the California National Primate Research Center and animal care procedures adhered to AAALAC and institutional guidelines. Earlier in life, some subjects were raised in other primate facilities under different housing conditions, including “standard” housing conditions and “small” cages. Group 1 (n = 23 subjects; mean age 25.4 ± 4.3 years) was obtained from several different primate centers and was housed throughout life in standard cages ranging in size from a minimum of 0.93 m3 to field cages of 1.3 acres, based on veterinary records. Some constituents of this group were reared in domestic primate centers, whereas others originated from Chinese or Indian sources. Records were sufficiently detailed to establish the accuracy of age estimates within a one-year time period. Group 2 (n = 7 subjects; mean age 25.9 ± 3.4), acquired late in life from a single facility, was raised from age 5–15 years in high density, single-monkey cages of size 0.72 m3 (i.e., these cages were at least 29% smaller than “standard” cages). Most primate investigators would agree that these cages are unusually diminutive, provide insufficient opportunity for exercise, and do not meet modern standards for primate housing. These subjects also originated from both domestic and foreign sources. After age 15 years, all monkeys were housed in standard-sized cages (minimum 0.93 m3). The investigators were made aware of the population of aged monkeys late in the primates’ life, in some cases only weeks before death, and for this reason additional studies such as cognitive characterization were not performed. The investigators confirmed the early environmental histories of the subjects by visiting the former housing facilities, reviewing early veterinary records, and conducting phone interviews with veterinarians or researchers from the original housing facilities. Findings in aged groups of subjects were compared to five young monkeys (age 8.4 ± 1.3 years) that were born and raised in standard-sized cages at the California National Primate Research Center.

2.2. Histology and immunocytochemistry

All subjects were perfused with 4% paraformaldeyhde with 10% picric acid, and brains were sectioned on a freezing microtome set at 40 µm thickness. Sections were singly immunolabeled for amyloid-containing plaques and synaptophysin, as indicated below. All quantification was performed by an investigator blinded to group identity.

β-Amyloid immunocytochemistry was performed using a modification of a previously described procedure (Mufson et al., 1994). Briefly, sections were immersed in 15% formic acid for 30 min, peroxide quenched, then incubated for 24 h in 10D5 monoclonal β-amyloid antibody (1:10,000 dilution; gift of D. Selkoe, Harvard Medical School). Sections were rinsed then incubated in biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG for 1 h, incubated in avidin-biotin complex (60 min at 1:500 dilution; “Elite” Kit, Vector Labs), and visualized with 2.5% nickel II sulfate, 0.05% 3’ 3’ diaminobenzidine (DAB) and 0.005% H2O2 (pH 7.4) (Hancock, 1982). Plaques were identified in histological sections (Fig. 1) by characteristic diffuse or condensed labeling of dark reaction product, and were quantified in the superior temporal gyrus using the fractionator method (Gunderson, 1986) and StereoInvestigator software (MicroBrightField, Inc.). Images were captured on an Olympus BX-60 microscope (New Hyde, NY) equipped with a Ludl Mac2002 motorized stage. 10% of total area outlined in the superior temporal gyrus was analyzed for plaque numbers to yield plaques/mm2 values. Plaques of both condensed and diffuse appearance were included in counts. The cross-sectional area of each plaque was also measured using the nucleator method (Gunderson, 1986). Plaque load was then calculated for each animal by dividing total plaquepositive area (the sum of nucleator area measurements) by total area analyzed (Mufson et al., 1999). Plaque density was sampled in 29 total subjects: 19 aged Group 1 monkeys (standard-cage reared; mean age 27.1 ± 0.8 years), five Group 2 monkeys (smaller-cage reared; mean age 26.8 ± 1.4 years) and five young monkeys. (Plaque labeling was not quantified in every subject in the study because comparable, matched sections of superior temporal gyrus were not available in every animal.) Because young monkeys had no detectable plaques, differences in β-amyloid density and load were statistically compared between aged groups, using two-sided Student’s t-test with a significance criterion of p < 0.05.

Fig. 1.

β-Amyloid plaques in the superior temporal gyrus of aged rhesus monkeys housed under either (A) standard or (B) small cage conditions (scale bar A, B, 0.65 mm). (C) Amyloid plaque density per mm2, and (D) amyloid load in superior temporal gyrus, were both elevated in primates raised in small cages (two-tailed t-test, *p < 0.001). Data for individual subjects are indicated by closed circles in A. Plaques were not detected in brains of young subjects.

Immunolabeling for synaptophysin was performed as previously described (Masliah et al., 1993). Briefly, four sections were randomly selected from matched regions of the superior temporal gyrus, separated by at least 320 µm. After peroxidase quenching, sections were incubated in primary anti-synaptophysin antibody (SY38, 1:75 dilution; Boehringer-Mannheim Labs., Indianapolis, IN) for 48 h at room temperature. After rinses, tissue was incubated for 1 h in horse anti-mouse FITC IgG (1:200 dilution; Vector Labs), mounted with Vectashield (Vector Labs), and examined under a Bio-Rad MRC-600 laser scanning confocal microscope (Watford, UK) mounted on a Nikon Optihot microscope (Tokyo, Japan). The aperture and gain levels were manually adjusted to obtain images with pixel intensities falling within a linear range. All sections were viewed with a 63× Nikon oil immersion lens combined with 10× ocular column magnification, and in all cases image acquisition was performed while maintaining constancy of confocal parameters. Digitized video images of gray matter in the region of interest was captured, and density of synaptophysin label in presynaptic terminals was determined in sections matched to β-amyloid labeled material, allowing examination of the same brain regions labeled for plaques. Digitalized images were filtered using standard software of the MRC-600 system, and the density of pixels per section immunlabeled for synaptophysin, with background subtracted, was measured using NIH Image software as previously described (Masliah et al., 1991). The average percentage of cortex labeled by synaptophysin per subject was measured. Synaptophysin immunoreactivity was sampled in 21 total subjects: 10 aged Group 1 monkeys (standard-cage reared; mean age 23.9 ± 3.0 years), six Group 2 monkeys (smaller-cage reared; mean age 25.7 ± 3.7 years), and five young monkeys. (Synaptophysin labeling was not quantified in every subject in the study because comparable, matched sections of superior temporal gyrus were not available in every case.) The mean age of the two groups of older monkeys did not differ significantly (p = 0.83). Values for synaptophysin immunoreactivity were compared between groups using ANOVA, with Fischer’s post-hoc test and a significance criterion of p < 0.05.

3. Results

Early environmental history was significantly associated with risk of amyloid plaque formation in the aged monkey cortex. Subjects raised in smaller cages exhibited a significant, 7.5-fold mean increase in both the density of β-amyloid plaques/mm2 and in amyloid plaque load in the superior temporal gyrus, compared to aged animals raised in standard-sized cages (Fig. 1; t-test, p < 0.001). Considerable individual variation was evident among aged subjects raised under small housing conditions, as indicated by plaque numbers in individual subjects (Fig. 1C), mirroring heterogeneity observed in aged human studies (Sisodia and Tanzy, 2007). In contrast, young brains contained no detectable amyloid plaques.

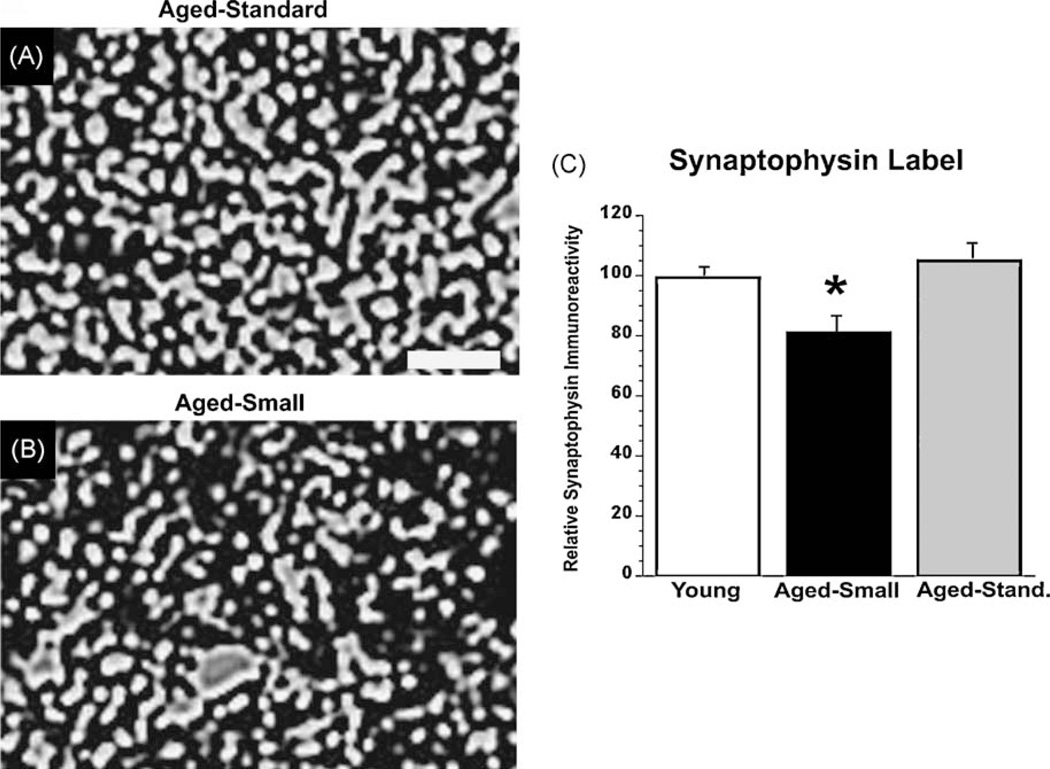

Rearing in small cages was also associated with a reduction in synaptophysin immunoreactivity, a presynaptic marker (Fig. 2). Aged monkeys raised in smaller cages exhibited a 16.7 ± 5.6% reduction in mean synaptophysin labeling in the superior temporal gyrus compared to aged monkeys raised in standard sized cages (ANOVA p < 0.01; p < 0.002, post-hoc Fisher’s comparing the two groups of aged subjects, and p < 0.05 comparing aged-small cage to young subjects). In contrast, aged monkeys raised in standard cage sizes demonstrated no significant reduction in mean synapse density compared to young monkeys (p = 0.98).

Fig. 2.

Synaptophysin immunoreactivity (Syn-IR) in the superior temporal gyrus of (A) a young adult monkey, and (B) an aged monkey from the small cage-rearing group. Scale bar, 1 µm. (C) Quantification of Syn-IR reveals a significant reduction in superior temporal gyrus in aged monkeys raised in small cages (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that structural features of the brain in the context of normal aging are influenced by early life experience. Monkeys reared in cages of small size exhibited a significantly increased density of amyloid plaques and a significant reduction in synaptophysin immunolabeling compared to aged monkeys raised under standard housing conditions. Synaptophysin is a protein associated with presynaptic vesicles, and its levels correlate with other synaptic markers, including PSD95 and GluR1 subunits, and with transmitter secretion (Alder et al., 1995, 1992; Liu et al., 2008; Song et al., 1997). Thus, observed increases in amyloid accumulation taken together with reductions in a synaptic marker suggest that a “constrained” early environment can lead to increased risk of pathological neurodegeneration in late life.

These findings parallel observations from human epidemiological studies suggesting that early life experience correlates with later life risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (Snowdon, 2003; Snowdon et al., 1996). However, unlike human epidemiological studies that address only the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease in relation to early life experience, our non-human primate study suggests that neuronal vulnerability in the course of normal aging is also influenced by early life experience. That is, aged primates do not develop Alzheimer’s disease (the triad of neurofibrillary degeneration, amyloid plaque deposition, and progressive cell loss), yet there exists a significant association of early life experience with development of late life indices of neural systems decline (plaque formation and reductions in a synaptic marker) in these aged monkeys. The nature of early life experience therefore has implications for both normal and pathological aging.

Several potential mechanisms may underlie the association of early life experience with late life plaque formation and synaptophysin reduction. For example, classic studies from the psychological literature indicate that high density housing increases stress (Mitchell, 1971), and stress leads to reductions in hippocampal dendritic spines (Sapolsky, 2000) that would in turn reduce synaptic markers. Alternatively, subjects in larger spaces have more opportunity for exercise, and exercise increases growth factor levels in the brain (Neeper et al., 1995) and levels of hippocampal neurogenesis (van Praag et al., 2005); these factors could enhance expression of synaptic markers. Lower levels of growth factors or synaptic activity resulting from a constrained environment could also directly influence amyloid turnover or processing, e.g., via altered levels of neprilysin, an amyloid-degrading enzyme (Lazarov et al., 2005).

Notably, synapse density appears to correlate with the degree of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease, and cognitive “engagement” or experience during life may increase synapse density and delay the time to express the clinical manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease (Snowdon et al., 1996). Thus, the present findings also suggest potential neural mechanisms that may underlie the correlation between early life experience and Alzheimer’s disease.

The observed differences in plaque load and a synaptic marker between groups of aged monkeys in this study may be attributable to factors other than cage size. To assess the early environment of subjects of this study, we visited the study sites, referred to veterinary records, and spoke to investigators at the original sites to confirm details of early life rearing. Yet it remains possible that differences in diet, stimulation, social interaction, stress or other factors between primate facilities earlier in life may also have contributed to the observed differences in this study. For example, monkeys were born either in China, India or the United States, and whether these distinctions might have affected study outcome is unknown. The potential, uncontrolled influence of these factors is an intrinsic limitation of retrospective studies, whether conducted in non-human primates (present study) or humans (Snowdon, 2003; Snowdon et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 1990). While there is less certainty regarding the findings of studies with retrospective elements compared to prospectively designed studies, some questions can only be addressed through retrospective means. The conditions under which a subset of aged monkeys in this study were housed are unlikely to be replicated in the future, and the opportunity to correlate brain pathology with early life experience is available only through retrospective analysis in this case. We find that early life experience is associated with degenerative change in the non-diseased aged brain, whereas previous human retrospective studies have established an association of early life experience with risk of developing a neurodegenerative disease, Alzheimer’s disease. Thus, our findings correlate with human findings but extend the effect of early environmental experience to perturbations of normal aging, with implications for “healthy aging”. While the retrospective nature of the study precludes the higher degrees of confidence associated with prospective studies, additional confidence in these findings is provided by the fact that all groups of subjects were housed under similar conditions in later life.

Thus, we infer that early environmental experience influences vulnerability to neurodegeneration. While consistent with human studies describing early environmental history as a risk factor for subsequently developing Alzheimer’s disease, these findings are notable for the fact that early experience is a risk for accelerated neural degeneration associated with normal aging.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH (AG10435) and the California Regional Primate Research Center Base Grant (RR00169), and the Shiley Family Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Alder J, Xie ZP, Valtorta F, Greengard P, Poo M. Antibodies to synaptophysin interfere with transmitter secretion at neuromuscular synapses. Neuron. 1992;9:759–768. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90038-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder J, Kanki H, Valtorta F, Greengard P, Poo MM. Overexpression of synaptophysin enhances neurotransmitter secretion at Xenopus neuromuscular synapses. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:511–519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00511.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu C, Colonnier M. Effects of the richness of the environment on six different cortical areas of the cat cerebral cortex. Brain Res. 1989;495:382–386. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comery TA, Stamoudis CX, Irwin SA, Greenough WT. Increased density of multiple-head dendritic spines on medium-sized spiny neurons of the striatum in rats reared in a complex environment. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 1996;66:93–96. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. A critical period for experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in rat barrel cortex. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:1826–1838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01826.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson HJG. Stereology of arbitrary particles. A review of unbiased number and size estimators and the presentation of some new ones, in memory of Willian R. Thompson. J. Microsc. 1986;143:3–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock MB. A serotonin-immunoreactive fiber system in the dorsal columns of the spinal cord. Neurosci. Lett. 1982;31:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(82)90028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Brandon EP, Gage FH. Environmental stimulation of 129/SvJ mice causes increased cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:939–942. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00377-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim JA, Lussnig E, Schwarz ER, Comery TA, Greenough WT. Synaptogenesis and Fos expression in the motor cortex of the adult rat after motor skill learning. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:4529–4535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04529.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarov O, Robinson J, Tang YP, Hairston IS, Korade-Mirnics Z, Lee VM, Hersh LB, Sapolsky RM, Mirnics K, Sisodia SS. Environmental enrichment reduces Abeta levels and amyloid deposition in transgenic mice. Cell. 2005;120:701–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Day M, Muniz LC, Bitran D, Arias R, Revilla-Sanchez R, Grauer S, Zhang G, Kelley C, Pulito V, Sung A, Mervis RF, Navarra R, Hirst WD, Reinhart PH, Marquis KL, Moss SJ, Pangalos MN, Brandon NJ. Activation of estrogen receptor-beta regulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity and improves memory. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:334–343. doi: 10.1038/nn2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Terry RD, Alford M, DeTeresa R, Hansen LA. Cortical and subcortical patterns of synaptophysinlike immunoreactivity in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol. 1991;138:235–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Mallory M, Hansen L, DeTeresa R, Terry RD. Quantitative synaptic alterations in the human neocortex during normal aging. Neurology. 1993;43:192–197. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.1_part_1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RE. Some social implications of high density housing. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1971;36:18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufson EJ, Benzing WC, Cole GM, Wang H, Emerich DF, Sladek JR, Morrison JH, Kordower JH. Apolipoprotein E-immunoreactivity in aged rhesus monkey cortex: colocalization with amyloid plaques. Neurobiol. Aging. 1994;15:621–627. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufson EJ, Chen EY, Cochran EJ, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Kordower JH. Entorhinal cortex beta-amyloid load in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Exp. Neurol. 1999;158:469–490. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeper SA, Gómez-Pinilla F, Choi J, Cotman C. Exercise and brain neurotrophins. Nature. 1995;373:109. doi: 10.1038/373109a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. Glucocorticoids and hippocampal atrophy in neuropsychiatric disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57:925–935. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ, Bell DS, Podlisny MB, Price DL, Cork LC. Conservation of brain amyloid proteins in aged mammals and humans with Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 1987;235:873–877. doi: 10.1126/science.3544219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisodia A, Tanzy R. Alzheimer’s Disease. San Diego: Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon DA. Healthy aging and dementia: findings from the Nun Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003;139:450–454. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-5_part_2-200309021-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon DA, Kemper SJ, Mortimer JA, Greiner LH, Wekstein DR, Markesbery WR. Linguistic ability in early life and cognitive function and Alzheimer’s disease in late life. Findings from the Nun Study. JAMA. 1996;275:528–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H, Ming G, Fon E, Bellocchio E, Edwards RH, Poo MM. Expression of a putative vesicular acetylcholine transporter facilitates quantal transmitter packaging. Neuron. 1997;18:815–826. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern RG, Mohs RC, Davidson M, Schmeidler J, Silverman J, Kramer-Ginsberg E, Searcey T, Bierer L, Davis KL. A longitudinal study of Alzheimer’s disease: measurement, rate, and predictors of cognitive deterioration. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1994;151:390–396. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Shubert T, Zhao C, Gage FH. Exercise enhances learning and hippocampal neurogenesis in aged mice. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:8680–8685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1731-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang MY, Katzman R, Salmon D, Jin H, Cai G, Wang Z, Qu G, Grant I, Yu E, Levy P, Klauber MR, Liu WT. The prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in Shanghai, China: impact of age, gender and education. Ann. Neurol. 1990;27:428–437. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]