Although the fecal occult blood test was designed primarily as a colorectal cancer screening tool for asymptomatic, nonhospitalized populations, it is being used for nonscreening purposes by some health care professionals, often without appropriate dietary and/or medication restrictions that, when not applied, can lead to false-positive results, which in turn lead to unnecessary referrals for endoscopy. Given the cost-conscious nature of the health care system, unnecessary or inappropriate testing does little to ease the burden on already strained health care resources. This retrospective study assessed the impact of in-hospital use of the fecal occult blood test on patient care in three acute care facilities in Hamilton, Ontario.

Keywords: Fecal occult blood test, FOBT, Gastrointestinal bleeding, GI bleed, Hospital, Inpatient

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The fecal occult blood test (FOBT) is a screening tool designed for the early detection of colorectal cancer in primary care. Although not validated for use in hospitalized patients, it is often used by hospital physicians for reasons other than asymptomatic screening.

OBJECTIVE:

To profile the in-hospital use of the FOBT and assess its impact on patient care.

METHODS:

Patient charts were retrospectively reviewed for all FOBTs conducted over a three-month period in 2011 by the central laboratory supporting the three acute care campuses of Hamilton Health Sciences (Hamilton, Ontario).

RESULTS:

A total of 229 patients underwent 351 tests; 52% were female and the mean age was 49 years (range one to 104 years). A total of 80 (34.9%) patients had at least one positive test. The most common indications for testing were anemia (51.0%) and overt gastrointestinal bleeding (19.2%). Only one patient had testing performed for asymptomatic colorectal cancer screening. In only 20 (8.7%) cases medications were modified before testing and diet was modified in only 21 (9.2%) cases. Most patients (85.2%) were taking one or more medications that could result in a false-positive result. Only 18 (7.9%) patients had a digital rectal examinations documented, of which seven were positive. All patients with a positive digital rectal examination underwent endoscopic procedures that revealed a source of bleeding. Among 44 patients with overt gastrointestinal bleeding, 12 (27.3%) had endoscopic investigations delayed to await results of the FOBT. Four patients were referred despite a negative FOBT due to a high degree of suspicion of gastrointestinal bleeding.

CONCLUSIONS:

The FOBT is often used inappropriately in the hospital setting. Confounding factors, such as diet and medication use, which may lead to false positives, are often ignored. Use of the FOBT in-hospital may lead to inappropriate management of patients, increased length of stay and increased direct medical costs. Use of the FOBT should be limited to validated indications only.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

La recherche de sang occulte dans les selles (RSOS) est un outil de dépistage conçu pour dépister rapidement le cancer colorectal en première ligne. Même s’il n’est pas validé chez les patients hospitalisés, il est souvent utilisé par les médecins en milieu hospitalier pour d’autres raisons qu’un dépistage asymptomatique.

OBJECTIF :

Brosser un tableau de l’utilisation de la RSOS en milieu hospitalier et en évaluer les répercussions sur les soins aux patients.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont procédé à l’analyse prospective des dossiers des patients pour en extraire toutes les RSOS effectuées une période de trois mois en 2011 par le laboratoire central recevant les examens des trois campus de soins aigus de Hamilton Health Sciences, de Hamilton, en Ontario.

RÉSULTATS :

Au total, 229 patients ont subi 351 tests, dont 52 % étaient de sexe féminin et qui avaient un âge moyen de 49 ans (plage de un à 104 ans). Au total, 80 patients (34,9 %) avaient subi au moins un test positif. Les principales indications des tests étaient l’anémie (51,0 %) et ces saignements gastro-intestinaux manifestes (19,2 %). Un seul patient avait subi des tests pour dépister un cancer colorectal asymptomatique. Dans seulement 20 cas (8,7 %), la médication avait été modifiée avant les tests et dans seulement 21 cas (9,2 %), le régime avait été modifié. La plupart des patients (85,2 %) prenaient au moins un médicament qui risquait de donner un résultat faux-positif. Seulement 18 patients (7,9 %) avaient subi un toucher rectal consigné au dossier, dont sept étaient positifs. Tous les patients dont le toucher rectal était positif avaient subi des interventions endoscopiques qui révélaient une source de saignement. Chez les 44 patients ayant des saignements gastro-intestinaux manifestes, 12 (27,3 %) ont vu leurs examens endoscopiques retardés dans l’attente des résultats de la RSIS. Quatre patients ont été dirigés malgré une RSIS négative en raison d’un fort degré de suspicion de saignement gastrointestinal.

CONCLUSIONS :

Souvent, la RSIS n’est pas utilisée à bon escient en milieu hospitalier. Des facteurs confusionnels sont souvent ignorés, tels que le régime et l’utilisation de médicaments qui peuvent susciter des résultats faux-positifs. L’utilisation de la RSIS en milieu hospitalier peut entraîner une prise en charge inadéquate des patients, une hospitalisation plus longue et des coûts médicaux indirects plus élevés. La RSIS devrait être limitée à des indications validées.

Fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) is a well-validated method to screen for colorectal cancer in asymptomatic populations (1). Screening FOBT allows for an increase in the detection of early-stage cancers and facilitates removal of precursor adenomas through selection of patients for colonoscopy. Recommendations for FOBT are based largely on randomized controlled trials conducted with a guaiac-based assay. A positive test results from oxidation of stool guaiac by hydrogen peroxide due to the peroxidase activity of hemoglobin. However, foods, such as red meat, turnip, broccoli, cauliflower and radishes, can lead to false positives, and some groups have advised dietary restriction for at least 72 h before testing (2–4). Vitamin C-containing products, such as citrus fruits, should also be avoided because of false-negative tests (2,5). If safe to do so, patients should avoid medications that may cause false positives for seven days, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants (2).

There is scant evidence supporting the use of FOBT in symptomatic patients. Several guidelines suggest only abdominal and rectal examination and a complete blood count are needed to decide which symptomatic patients warrant referral (6,7). Canadian guidelines suggest that FOBT is not sufficiently sensitive for use in high-risk patients such as those with symptoms (7). Despite this, the FOBT is often used by primary care physicians, internal medicine residents and gastroenterologists to evaluate symptomatic inpatients for indications other than colorectal cancer screening, and often without adequate dietary or medication restriction (8–10). This can lead to false-positive test results and unnecessary referrals for endoscopic investigations with low diagnostic yield. In cost-conscious health care settings, this may be an ineffective approach to symptomatic patients. The aim of the current study was to examine the use of FOBT in the inpatient setting by conducting a retrospective analysis of patterns of use, indications, and impact on patient care and health care resources.

METHODS

A retrospective study was performed to review all FOBTs performed by the central laboratory supporting the three acute care campuses of Hamilton Health Sciences (Hamilton, Ontario). All FOBTs conducted for adult and pediatric inpatients over a three-month period in 2011 were included in the study. Each patient record was reviewed by clinicians who were not involved in the care of the patients. Data regarding patient age, sex, admitting diagnosis, symptoms, digital rectal examination (DRE) findings, rationale for FOBT (if documented and decipherable), medication and diet restrictions, referral for gastroenterology assessment and results of endoscopic investigations were recorded using a standardized data collection instrument. Overt gastrointestinal bleeding was defined as any of hematemesis, coffee-ground emesis, melena, hematochezia or bright red blood per rectum. A DRE was considered to be positive if there was any evidence of bright red blood, melena or a mass lesion. Any antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and vitamin C supplements used at the time of FOBT were recorded. Where applicable, the impact referral for endoscopic investigations had on length of stay in hospital was assessed based on hospital progress notes documenting whether the patient was otherwise ready for discharge. An investigator not involved with data extraction (NN) was responsible for analysis of the data. For cases in which the impact of FOBT on clinical decision making or length of stay in hospital was not clear, it was recorded as ‘indeterminable.’

In an independent study, a questionnaire was distributed among health care providers within the local health integration network to survey practice patterns and rationale for FOBT use. All health professionals who used FOBT kits for inpatient investigation were asked to participate including physicians, medical residents, nurse practitioners and nurses. Both studies were approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

A total of 229 patients underwent 351 FOBTs during the three-month period analyzed. The mean age of patients studied was 49 years (range one to 104 years) including 18 pediatric patients and 120 (52.4%) females. A total of 83 patients (36.2%) were admitted under general internal medicine, two (0.9%) were admitted under gastroenterology and the remaining 144 (62.8%) were admitted under other subspecialties of medicine and pediatrics, or under surgery. Emergency physicians often perform FOBT as a point-of-care test and usually do not send the tests to the central laboratory. As such, none of the subjects included in the present analysis had FOBT performed in the emergency room.

Impact of positive FOBT results

In 80 (34.9%) patients, at least one FOBT was positive. Almost one-half of these patients (36 of 80 [45.0%]) had overt gastrointestinal bleeding. Interestingly, only 40 patients with positive FOBT (50%) were referred to gastroenterology, of whom 23 had overt bleeding. The remaining 40 (50%) patients with positive FOBT who were not referred included 13 with overt bleeding. Among the 13 patients with overt bleeding who were not referred, reasons for not pursuing endoscopic assessment included suspected hemorrhoidal or local anorectal pathology in four (30.8%), limited goals of care in two (15.4%) and febrile neutropenia in one (7.7%).

A total of 79 patients underwent ≥2 FOBTs and the mean number of tests conducted per patient was 1.53 (range one to six). Twenty-six patients had ≥2 positive FOBTs; of these, 15 (58%) were referred to gastroenterology. Gastroenterology performed endoscopic investigations in 80% (12 of 15) of these patients. Of 54 patients with only one positive FOBT, 25 (46%) were referred to gastroenterology, of whom 19 (76%) underwent endoscopic investigation.

Among the 18 pediatric patients with FOBTs sent, seven (38.9%) had positive results. One of these patients was referred for gastrointestinal evaluation and underwent a colonoscopy that diagnosed Crohn disease.

Indications for FOBT

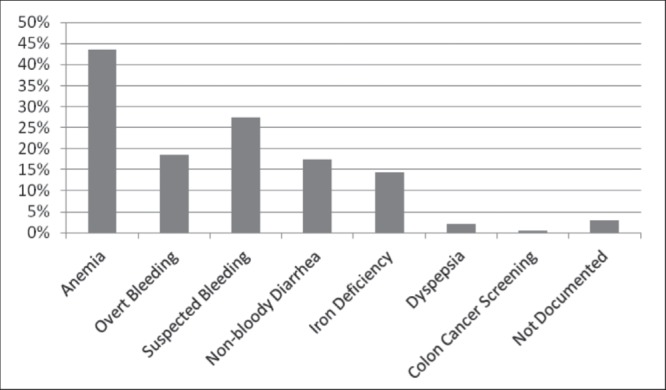

Figure 1 summarizes the indications for FOBT suggested by hospital progress notes and physician orders. The majority of tests were ordered for anemia, of which 51 of 117 (43.6%) were positive and 23 were referred to gastroenterology. A potential gastrointestinal cause for anemia was identified in only eight of these patients for a yield of 6.8% (eight of 117). Thirty-three patients had FOBT performed for iron deficiency anemia. Among 25 such patients with negative tests, two were referred for endoscopic investigations and one had colorectal cancer. Of eight patients with positive FOBT and iron deficiency anemia, five were referred for endoscopic investigation.

Figure 1).

Indications for ordering fecal occult blood tests

Surprisingly, 44 (18.4%) patients underwent FOBT to investigate overt bleeding, and 63 (27.5%) underwent FOBT for suspected gastrointestinal bleeding based on a decline in hemoglobin level. Only one patient was asymptomatic and underwent FOBT to screen for colorectal cancer. The rationale for FOBT could not be determined in seven (3%) patients.

DRE

Only 18 (7.9%) patients who underwent FOBT had a documented DRE, with positive results in seven (3.1%). Among these seven patients with a positive DRE, six had positive FOBT, but all seven were referred for endoscopic investigation that identified a source of bleeding. Eight of 11 patients with a negative DRE were referred for endoscopic investigations and four had a source of bleeding identified. Twelve of the patients who had DRE performed had symptoms of overt gastrointestinal bleeding, and a source of bleeding was identified endoscopically in 11.

Diet and medications before FOBT

Although 195 (85.1%) patients used medications that could affect testing, there was evidence of medication restriction in 20 (8.7%) (Table 1). Of those using medications associated with increased false-positive FOBT, 97 (42.4%) were taking one medication, 43 (18.8%) were taking two and 53 (23.1%) were taking three. Dietary restriction was documented in only 21 (9.2%) patients. Among the 64 patients with positive FOBT, but no dietary or medication restriction, seven (10.9%) had normal endoscopic investigations.

TABLE 1.

Concomitant medications that can interfere with fecal occult blood testing

| Medication | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 121 (53) |

| Unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin | 124 (54) |

| Warfarin | 40 (17) |

| Clopidogrel | 25 (11) |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 14 (6) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | 22 (10) |

| Vitamin C | 1 (0) |

Endoscopic investigations

From the 229 patients who had FOBT performed, 44 (19.2%) were referred to gastroenterology, including four with negative FOBT. Of these, 24 (54.5%) underwent endoscopy as inpatients, seven (15.9%) underwent endoscopy as outpatients, and 13 (29.5%) had either no endoscopy or plans for endoscopy outside Hamilton Health Sciences. Of 31 patients who underwent investigation, 14 (45.1%) underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) alone, three (9.7%) underwent colonoscopy alone and 14 (45.1%) had both procedures performed.

Table 2 reports endoscopic findings and corresponding FOBT results. Of 14 patients who underwent EGD only, 13 (92.9%) had a positive FOBT, 10 (71.4%) were anemic, nine (64.3%) had overt bleeding at presentation, five (35.7%) were suspected to have bleeding and three (21.4%) were iron deficient. Of three patients who underwent colonoscopy only, two (66.7%) had positive FOBT, two (66.7%) were anemic, one (33.3%) had overt bleeding, one (33.3%) was suspected to have bleeding and one (33.3%) was iron deficient (one patient with negative FOBT and iron deficiency anemia underwent colonoscopy that revealed a rectosigmoid adenocarcinoma). Of 14 patients who underwent both EGD and colonoscopy, 12 (85.7%) had positive FOBT, 12 (85.7%) were anemic, eight (57.1%) had overt bleeding, three (21.4%) were suspected to have bleeding and three (21.4%) were iron deficient.

TABLE 2.

Findings at endoscopy for patients referred after fecal occult blood testing (FOBT)

| Findings at upper gastrointestinal endoscopy | FOBT | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Ulcer | 12 | 0 | 12 |

| Normal | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| Gastritis | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Esophagitis | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Polyp(s) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Findings at colonoscopy | |||

|

| |||

| Normal | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Colitis | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Diverticular bleeding | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Hemorrhoids | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Polyp(s) | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Ulcer | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Crohn disease | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cancer | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Data presented as n

Impact on patient care

Among 44 patients with overt bleeding, 12 (27.3%) had referral to gastroenterology delayed until the result of FOBT was known. In this cohort, nine patients had negative FOBT (20.5%) and eight were not referred for endoscopy. Four (9.1%) patients referred for positive FOBT were subsequently found to have gastrointestinal infections.

Among the 44 patients referred to gastroenterology, 40 (90.9%) had positive FOBT and 24 (54.5%) were investigated as inpatients. Thirteen (29.5%) patients with FOBT had their hospital stay prolonged for investigation, with a total increase in length of stay of 26 days. Reasons for this increase included preparation for endoscopy and endoscopy-related complications such as oversedation or incomplete assessment.

Four patients were referred to gastroenterology despite negative FOBT, of whom one had overt bleeding on presentation, and three had anemia and suspected bleeding (including one with liver metastasis on imaging).

Survey of FOBT practice patterns

The results of the entire eight-question survey are presented in the Appendix. Questions that were relevant to FOBT practice patterns were selected for discussion here. There were a total of 67 respondents. Question 3 (Appendix Table 3) assessed the main reasons that the health care providers ordered FOBTs. Only 27.9% (17 of 61) of health care providers used this test for colorectal cancer screening. Other common reasons for using this test included investigation of symptoms consistent with gastrointestinal bleeding (93.4% [57 of 61]), uninvestigated anemia (59% [36 of 61]), iron deficiency anemia (34.4% [21 of 61]) and overt gastrointestional blood loss (29.5% [18 of 61]). Question 6 (Appendix Table 6) asked who was responsible for performing the FOBT. Of the 67 respondents to this question, the majority acknowledged that the attending physicians (62.3% [42 of 67]) or nurses (55.2% [37 of 67]) were responsible for performance and processing of these tests. Question 7 (Appendix Table 7) assessed knowledge regarding factors that could alter the FOBT result. Of the 57 respondents, 77.2% (44 of 57) were aware dietary restrictions are necessary and 68.4% (39 of 57) were aware certain medications could impact the test result.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present audit and survey suggest that, although FOBT is only validated for use in asymptomatic ambulatory patients for colorectal cancer screening, it is frequently used for assessment of symptomatic hospitalized patients. The positivity rate demonstrated in the present study (34.9%) was less than that reported in other studies investigating inpatient FOBT use (51% to 65%) (11,12).

FOBT has several limitations when used for inpatients, including noncompliance with restriction of diet and medications that could affect test results. These factors are considered in <10% of patients who undergo testing, even though most respondents to our survey were aware of their potential impact on test performance. As a result, there may be false positives that lead to referral for unnecessary endoscopic investigations and additional days in hospital. Seven of 64 (10.9%) patients with a positive FOBT, but no documented dietary or medication restriction, had normal endoscopic examinations. Furthermore, a positive FOBT appears to have a low diagnostic yield. One-half of the patients with positive FOBT were not referred for further assessment, despite evidence of overt bleeding in 13 of 40 (32.5%) patients. This was also observed in the pediatric population, in which 85.7% of positive tests were not referred, and the one patient who was referred had other clinical features suggestive of inflammatory bowel disease that would have warranted gastroenterology consultation. Because these positive FOBT results did not appear to affect the clinical decision to initiate referral for gastroenterology assessment, the FOBT likely should not have been performed in the first place. Even having multiple positive tests did not appear to further increase the likelihood of referral for gastroenterology consultation or endoscopic investigation.

Similarly, four patients were referred for gastroenterology assessment despite a negative FOBT. One of these patients had overt bleeding; another who proved to have colorectal cancer had other compelling clinical features. In fact, some pathologies can bleed intermittently and generate false-negative FOBT results. For patients with high pretest probability of gastrointestinal bleeding, FOBT should not be performed as a negative test and does not deter the clinical decision to refer for investigation. Such inappropriate testing may be common because 29.5% of health care providers who responded to our survey acknowledged using FOBT to assess patients with overt gastrointestinal bleeding.

Inappropriate use of FOBT may also delay appropriate patient care. More than one in four patients with overt gastrointestinal bleeding had their referral for investigation delayed to wait for FOBT results, even though some of these patients were referred anyway despite a negative FOBT. Because of its limited sensitivity, a negative FOBT should not prevent referral for patients with other features of bleeding. It is of concern that only two of 25 (8%) patients with iron deficiency anemia and negative FOBT were referred, even though this is a widely accepted indication for endoscopic evaluation (13).

The DRE is considered to be an essential part of the physical examination for patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. In addition to detecting anorectal pathology, DRE can help differentiate melena from bright red bleeding to help target endoscopic investigation. Only 7.9% of patients in the study cohort had a DRE documented in the chart. This is significantly lower than the rate of 44.8% reported in the study by Sharma et al (11), and may reflect the fact that FOBT is not performed by physicians but submitted by nursing staff on a physician’s order. All seven patients with overt bleeding at DRE had a source of bleeding identified at endoscopy and likely did not benefit from FOBT. Furthermore, performing FOBT on samples obtained by DRE is not recommended because false-positive results can result from anorectal trauma (14). Institutional policies requiring DRE in patients with suspected gastrointestinal bleeding would decrease the volume of FOBT performed because they would not be submitted for patients with bright red blood or melena.

The present study had several limitations. Its retrospective design relies on adequate documentation of clinical actions and decisions in the patient chart. Inadequate documentation regarding performance of DRE, for instance, could explain its apparently low rate. Reasons for FOBT or gastroenterology referral are often poorly explained. Our data also reflect a relatively small sample and practice at an academic tertiary care centre, and may not represent practice in other settings.

CONCLUSIONS

FOBT is often misused in the inpatient setting. While some physicians advocate its use to evaluate anemia or iron deficiency, or to triage patients with bleeding, it seldom impacts clinical decision making as to whether to refer patients for investigation. Dietary and medication modification in the inpatient setting is often insufficient or impractical, leading to false-positive tests and unnecessary investigations. Furthermore, its use can delay investigation and increase length of stay. In most scenarios in which FOBT is performed, clinicians can make decisions based on a composite of history, physical examination with DRE and other laboratory investigations. Other authors have similarly concluded that the FOBT does not have a role in the evaluation of symptomatic patients because it rarely impacts clinical management (11,12,15,16). Until FOBT is proven to have utility in acute care hospitals, it should not be used as a substitute for proper patient assessment. Collaboration among hospital-based physicians, nurses, gastroenterologists and hospital administrators is needed to educate health care providers regarding the proper use of FOBT in the assessment of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding.

APPENDIX TABLE 1.

Please provide information regarding your primary practice site and position title

| Practice site (Ontario) | Physician | Nurse practioner | Nurse | Health care aide | Senior medical resident | Junior medical resident | Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brant Community Health System | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Haldimand War Memorial Hospital | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hamilton Health Sciences | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Hotel Dieu Shaver Health and Rehab Centre | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Joseph Brant Memorial Hospital | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Niagara Health System | 6 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Norfolk General Hospital | 3 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| St Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| West Haldimand General Hospital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| West Lincoln Memorial Hospital | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Other hospital or position title (please specify) | 0 |

Data presented as n. Answered question n=67; Skipped question n=1

APPENDIX TABLE 2.

What is your clinical area?

| Answer option | Response, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Emergency department | 34 (50.0) |

| Intensive care | 4 (5.9) |

| Urgent care | 7 (10.3) |

| General medicine | 9 (13.2) |

| Other (please specify) | 18 (–) |

Answered question n=54; Skipped question n=14

APPENDIX TABLE 3.

What are the main reasons you order a fecal occult blood test? (check all that apply)

| Answer option(s) | Response, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Symptoms potentially consistent with gastrointestinal bleeding | 57 (83.8) |

| Anemia for investigation | 36 (52.9) |

| Iron deficiency with or without anemia | 21 (30.9) |

| Overt gastrointestinal blood loss | 18 (26.4) |

| Nonbloody diarrhea | 7 (10.2) |

| Screening for colorectal cancer | 17 (25.0) |

| Pre-initiation of anticoagulation with warfarin | 0 (0.0) |

| Consult for gastroenterology | 8 (11.7) |

| Other (please specify) | 6 (–) |

Answered question n=61; Skipped question n=7

APPENDIX TABLE 4.

What is the approximate turn-around-time required for the test result?

| Answer option | Response, n (%) |

|---|---|

| <5 min | 23 (33.8) |

| 15 min | 2 (2.9) |

| 30 min | 5 (7.4) |

| 1 h | 8 (11.7) |

| 2 h | 6 (8.8) |

| Not urgent | 18 (26.4) |

Answered question n=62; Skipped question n=6

APPENDIX TABLE 5.

What determines how the test is ordered?

| Answer option(s) | Response, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Medical directive | 3 (4.4) |

| Standard of pratice guideline | 6 (8.8) |

| Physician order | 53 (77.9) |

| Care path or order set | 1 (1.5) |

| Other (please specify) | 9 (–) |

Answered question n=61; Skipped question n=7

APPENDIX TABLE 6.

Who in your clinical area performs the fecal occult blood test? (check all that apply)

| Answer option(s) | Sample collection | Processes test | Records test result | Response | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Electronic database | Patient chart | ||||

| Attending physician | 42 | 21 | 2 | 26 | 91 |

| Nurse practioner | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Nurse | 37 | 19 | 7 | 19 | 82 |

| Health care aide | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Senior medical resident | 10 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 23 |

| Junior medical resident | 9 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 22 |

| Other (specify position title in box below) | 1 | 14 | 16 | 6 | 37 |

| Position title | 13 | ||||

Data presented as n. Answered question n=67; Skipped question n=1

APPENDIX TABLE 7.

Are there any factors you are aware of which may affect the test result?

| Answer option(s) | Response, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Diet restrictions | 44 (64.7) |

| Medication interferences | 39 (57.3) |

| Minimum time stool must be in contact with the paper | 21 (30.9) |

| Patient temperature | 3 (4.4) |

| Color or consistency of stool | 11 (16.1) |

| Other (please specify) | 0 (–) |

Answered question n=57; Skipped question n=11

APPENDIX TABLE 8.

How will the fecal occult test result be used?

| Answer option(s) | Response, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Screening test to determine what further investigations are required | 59 (86.7) |

| Determines how patient will be triaged | 7 (10.2) |

| Other (please specify) | 0 (–) |

Answered question n=62; Skipped question n=6

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Irwig L, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test. Hemoccult Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;24:CD001216. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001216.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin B, Lieberman D, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008. A joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:130–60. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feinberg E, Steinberg W, Banks B, et al. How long to abstain from eating red meat before fecal occult blood tests. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:403–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-5-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson MH, Moss S, Hardcastle J, et al. Effect of retesting with dietary restriction in haemoccult screening for colorectal cancer. J Med Screen. 1995;2:41–4. doi: 10.1177/096914139500200111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaffe R, Kasten B, Young D, et al. False-negative stool occult blood tests caused by ingestion of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) Ann Intern Med. 1975;83:824–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-83-6-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE. Clinical Guideline 27: Referral for Suspected Cancer. < www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/cg027niceguideline.pdf> 2005 (Accessed June 23, 2013)

- 7.Leddin D, Hunt R, Champion M, et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology and the Canadian Digestive Health Foundation: Guidelines on colon cancer screening. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:93–9. doi: 10.1155/2004/983459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma V, Vasudeva R, Howden C. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance practices by primary care physicians: Results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1551–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma V, Corder F, Raufman J, et al. Survey of internal medicine residents’ use of the fecal occult blood test and their understanding of colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2068–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma V, Corder F, Fancher J, et al. Survey of the opinions, knowledge and practices of gastroenterologists regarding colorectal cancer screening and the use of the fecal occult blood test. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3629–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma V, Komanduri S, Nayyar S, et al. An audit of the utility of inpatient fecal occult blood testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1256–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman A, Chan A, Chin L, et al. Use and abuse of faecal occult blood tests in an acute hospital inpatient setting. Intern Med J. 2010;40:107–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.02149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paterson W, Depew W, Paré P, et al. Canadian consensus on medically acceptable wait times for digestive health care. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:411–23. doi: 10.1155/2006/343686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ransohoff D, Lang C. Screening for colorectal cancer with the fecal occult blood test: A background paper. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:811–22. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-10-199705150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peacock O, Watts E, Hanna N, et al. Inappropriate use of the faecal occult blood test outside of the National Health Service colorectal cancer screening programme. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1270–5. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328357cd9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rijn A, Stroobants A, Deutekom M, et al. Inappropriate use of the faecal occult blood test in a university hospital in the Netherlands. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1266–9. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328313bbd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]