Abstract

The home is increasingly associated with asthma. It acts both as a reservoir of asthma triggers and as a refuge from seasonal outdoor allergen exposure. Racial/ethnic minority families with low incomes tend to reside in neighborhoods with low housing quality. These families also have higher rates of asthma. This study explores the hypothesis that black and Latino urban households with asthmatic children experienced more home mechanical, structural condition–related areas of concern than white households with asthmatic children. Participant families (n = 140) took part in the Kansas City Safe and Healthy Homes Program, had at least one asthmatic child, and met income qualifications of no more than 80% of local median income; many were below 50%. Families self-identified their race. Homes were assessed by environmental health professionals using a standard set of criteria and a specific set of on-site and laboratory sampling and analyses. Homes were given a score for areas of concern between 0 (best) and 53 (worst). The study population self-identified as black (46%), non-Latino white (26%), Latino (14.3%), and other (12.9%). Mean number of areas of concern were 18.7 in Latino homes, 17.8 in black homes, 13.3 in other homes, and 13.2 in white homes. Latino and black homes had significantly more areas of concern. White families were also more likely to be in the upper portion of the income. In this set of 140 low-income homes with an asthmatic child, households of minority individuals had more areas of condition concerns and generally lower income than other families.

Keywords: Air quality, allergens, asthma triggers, children, environment, Healthy Homes Program, housing quality, low-income, minority, urban

The home is an important exposure site for various indoor allergens1 and it is a major predictor of health.2 Evidence has shown a strong relationship between housing quality and health outcomes.3 Low-income, racial/ethnic minority neighborhoods carry a disproportionate burden of substandard and poor quality housing, especially in urban areas.2,4–6 A review of asthma prevalence in urban and rural environments highlighted the existence of a socioeconomic dichotomy that affects access to and quality of health care.7 Although some rural areas may have similar risks for the development of asthma as urban areas, urban environments generally model the factors necessary to lead to the predisposition for asthma.7 According to The State of the Nation's Housing report, approximately 1 in 10 U.S. low-income families live in inadequate housing.8 Close to one-half of these low-income families spent more than one-half of their income on their inadequate housing,8 making it near impossible to afford improvements to address the inadequacies.5

Substandard housing and indoor environmental exposures have been linked to increased indoor allergen exposure and sensitization9,10 and greater asthma morbidity and mortality for low-income racial/ethnic minority children living in urban areas.11 Poor quality housing can harbor indoor allergens and triggers. Excess moisture allows for the breeding of mites, mold, and cockroaches.4,11,12 Cracks allow pests such as rodents and bugs to enter the home.12 Inadequate ventilation can result in high concentrations of environmental tobacco smoke, allergens, carbon dioxide, radon, and volatile organic compounds.12 The effects of these household airborne exposures on asthma are very complex. They can be further modified by many coexposures such as endotoxin and nitrogen oxides further complicating the relationships between indoor environmental parameters and asthma-related outcomes.13 In addition to indoor environmental exposures, low-income racial/ethnic minority neighborhoods tend to be situated adjacent to highways and bus depots; proximity to areas of large vehicle traffic results in ambient particulate matter and diesel fumes pervading from the outside and high lead contamination of the plants and dirt.5 Findings from a cross-sectional study among children <6 years of age revealed that roughly 39% of doctor-diagnosed cases of asthma among children in the United States could be avoided by eliminating indoor environmental exposures.14

Asthma is typical among U.S. racial/ethnic minority children living in urban areas.15 In fact, the rates of asthma are rising in the United States.16 The prevalence of asthma from 2008 to 2010 was highest among blacks and American Indians/Alaska Natives.16 Black children have seen the greatest rise in asthma prevalence rates, with just under a 50% increase from 2001 to 2009.16 Although the causes of asthma are still unclear, strong evidence suggests that indoor environmental exposures play a major role.2,5,11–15,17,18 The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology stresses the control of exposures to indoor allergens and environmental tobacco smoke as an important part of an asthma management plan.19 However, it is unclear how the structural condition of homes among asthmatic subjects varies by race.

To explore the relationship of race and housing condition among low-income families, we examined the domiciles of non-Latino white, black, and Latino households enrolled in the Kansas City Safe and Healthy Homes Program (KCSHHP). We hypothesized that black and Latino households experienced more home maintenance concerns in the home and children in those households have more asthma-related issues when compared with non-Latino whites enrolled in the study. The sample sizes for American Indians and Asians were insufficient to provide stable estimates of both asthma and home maintenance concerns; therefore, they are not included in the analyses.

METHODS

Participant Recruitment

Homes in this study participated in KCSHHP between 2008 and 2012. Children with a history of asthma, whose families could potentially qualify for the program, were identified from the Children's Mercy Hospital (CMH) Emergency Room, the CMH Allergy Clinic, other CMH primary care clinics, community physicians and clinics, and organizations affiliated with the KCSHHP including health departments and housing authorities. Participants in the program had to meet certain criteria to enroll in the program including;

The family must provide proof of home ownership or the ability to show a consistent rental history and cooperation of the landlord for the remediation.

The family must have lived in the same home for the last 6 months and expected to stay in that home for the next 12 months.

The family must have at least one asthmatic child resident in the home a minimum of 4 days/wk.

All families in the program must meet income qualification guidelines of <80% of median family income for the area (Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD] requirement).

Homes must not be in a flood plain or in a historical area or associated with public housing (HUD requirement).

Asthmatic severity was assessed at a scheduled clinic visit and ranged from mild persistent to severe. Children were not allowed to proceed with the study if their asthma was determined to be uncontrolled. This policy was put in place to ensure that a family did not substitute the environmental interventions offered for proper medical care. If the initial examination revealed a child with uncontrolled asthma, their participation was delayed until that child's asthma was treated and the control status was deemed to be adequate. Recruitment was conducted through the CMH clinic or through local allergists' offices; therefore, a child with uncontrolled asthma was rare. Study records indicate that only one family's participation was delayed for poor asthma control. If initial screening indicated the family would benefit from participation in the program, the family was enrolled and a health evaluation visit was scheduled. Financial support was provided by the HUD as a Healthy Homes Initiative Demonstration Grant awarded to CMH to provide home and health assessments and analytical services. All human subjects' elements of this study were reviewed and approved by the CMH Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians and assent was obtained from the child participant when applicable.

Participants in the study completed an extensive questionnaire on enrollment that collected information including demographic items, medical history, and personal health habits. All participants were asked to self-identify association with one of six racial/ethnic categories including black, American Indian, Asian, non-Latino white, Latino, and other. Medical history included history of asthma, steroid use for asthma, frequency of cough, frequency of wheeze, frequency of shortness of breath, and asthma control test (ACT) score. Personal health habits questions included history of parental smoking; family members' smoking status; smoking in the home; and presence of cats, dogs, and/or other pets.

Home Assessments

Participant homes were assessed by environmental health specialists from the CMH Center for Children's Environmental Health. The certified environmental health specialists were certified in the Healthy Homes Curriculum of the National Center for Safe and Healthy Housing. Home environments were scored using a standard set of criteria and a specific set of on-site and laboratory sampling and analyses.20 The assessments looked at six to seven general problem areas including air quality, allergens and dust, moisture control, chemical exposure and safety, and injury prevention. Each general problem area required the evaluation of several elements based on a 3-point scale. For example, the general problem area of allergens and dust comprised 11 elements that were evaluated, including mold smell, visible pests, carpeting condition, and clutter. Evaluation also included an assessment of the overall structural and mechanical systems of the home. Specific analytical parameters included measurement of temperature; humidity; carbon dioxide; carbon monoxide; airborne particulates; airborne fungal spores; and dustborne allergens from cats, dogs, dust mites, mice, roaches, Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus fumigatus, Cladosporium herbarum, and Penicillium chrysogenum. At least six rooms in the home, including the asthmatic child's bedroom and the basement/utility area, were evaluated. Additionally, an outdoor collection of pollen and spores was collected at each home for comparison with indoor spore levels. This information was considered when noting an air quality maintenance concern. Overall, each home was evaluated for >250 specific points in 53 areas of maintenance concerns. Theoretical scores ranged from 0 (best) to 53 (worst).

Efforts were undertaken in the study to prevent any bias in the persons evaluating the homes or analyzing the data. The homes were evaluated by at least one of four individuals. The evaluators all used the same multicomponent checklist developed by the CMH Center for Children's Environmental Health. Individual evaluators routinely conducted home assessments in groups to synchronize methods and results. Home evaluations were discussed at regular meetings to maintain constancy. After the data sets were assembled and before statistical analysis was performed, all names, addresses, and personal health information was removed.

Data and Statistics

Descriptive statistics were computed using an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and comparative statistics were computed and displayed using the SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary NC) and the SPSS software (IBM, Chicago, IL). A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant beyond a chance occurrence.

RESULTS

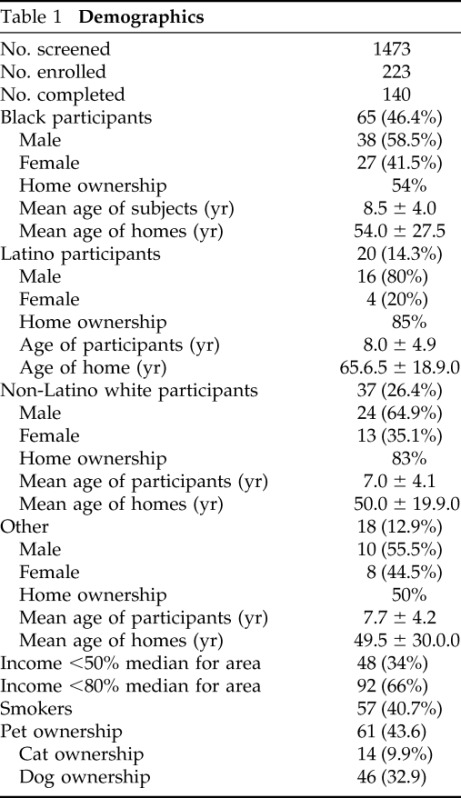

The KCSHHP screened a total of 1473 families for enrollment and 382 families were enrolled. We discuss the 140 families with severe asthmatic children that received full home evaluations. Reasons participants were not enrolled in the study included failure to complete enrollment information, income >80% of median family income, and plans to relocate during the time of the study. Reasons participants did not complete the study included repeated failure to meet appointments, lost communication, or unplanned relocation (83 families). A majority of study participations self-identified as black (46%), followed by non-Latino white (26%), and Latino (14.3%). No participants self-identified as American Indian. Two participants identified as Asian. All individuals who identified as more than one racial/ethnic group were included in the “other” category. For all racial/ethnic groups, male asthmatic children represented a higher portion than female asthmatic children. The mean age of black asthmatic children was slightly higher than non-Latino white children in the study but the difference was not statistically significant. Demographics for study participants are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the homes of the Latino and black asthmatic children was greater than that of the non-Latino white asthmatic children; however, the deviation in the age of the homes was very large and the differences were not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Demographics

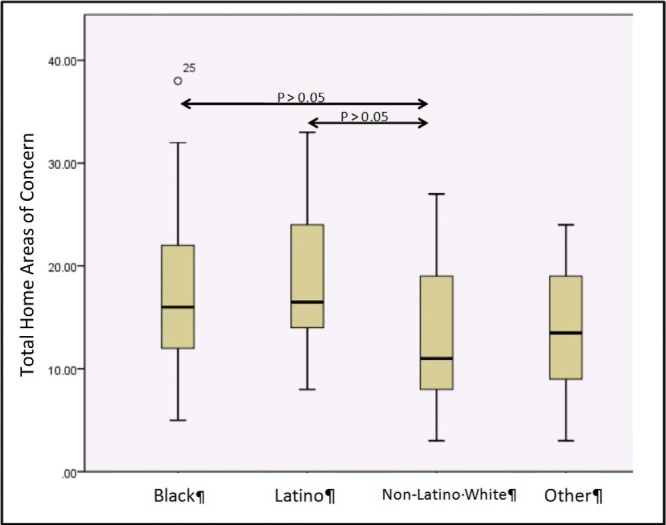

The number of specific maintenance concerns per home ranged from a low of 3 to a high of 38 as depicted in Fig. 1. On average, the homes of black children in the study had more maintenance concerns (17.2) than homes of non-Latino white children (13.2) and fewer than homes of Latino children (18.7). Comparative statistics for home inspection results are shown in Table 2. Overall, 66% of the homes were owner occupied and 34% were rentals (Table 1). The “other” group had the lowest percentage of home ownership (50%) followed by black (54%), non-Latino white (83%), and Latino participants (85%). Home ownership was significantly different between non-Latino white and black participants (p < 0.01) and between Latino and black participants (p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Box plot comparison of total home inspection areas of safety and maintenance concerns in the homes of more severe asthmatic patients for self-identified racial/ethnic associations in the Kansas City Safe and Healthy Homes Program (KCSHHPs). Black and Latino participants are significantly different from non-Latino white participants.

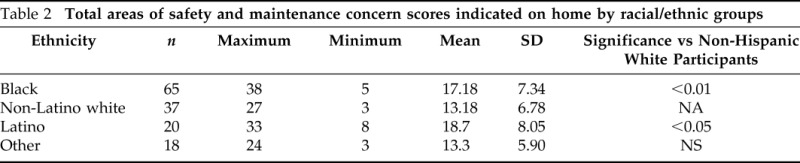

Table 2.

Total areas of safety and maintenance concern scores indicated on home by racial/ethnic groups

A comparison of the maintenance concerns data for the homes is presented in Fig. 1. The box plot represents graphically the mean, quartiles, and upper/lower limits of the data including outliers represented by individual circular data points. For all calculated variables, the homes of non-Latino white asthmatic children in the study had fewer maintenance concerns than the homes of either black asthmatic children or Latino asthmatic children. Both of these differences were significant at the 95% confidence level or greater.

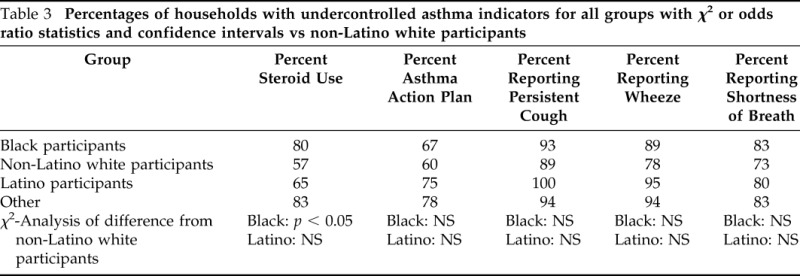

The prevalence of asthma-related parameters for all groups is shown in Table 3. The only significant difference observed was that black asthmatic children had an increased use of steroid medication over non-Latino white asthmatic children. Other measured parameters including receipt of an asthma action plan and recollection of persistent cough, wheezing, or shortness of breath were not significantly different among the groups. The mean ACT test score was highest in non-Latino white children (19.2) and lower in black (16.5) and Latino children (18.8) but the differences did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

Percentages of households with undercontrolled asthma indicators for all groups with χ2 or odds ratio statistics and confidence intervals vs non-Latino white participants

Income level was a parameter controlling entry into the study by guidelines of the funding agency and was set at a maximum <80% of median family income for the metropolitan area, adjusting for the number of family members. Also, the statistics on family income <50% of the median family income was retained. Overall, the lower-income group had more maintenance concerns in the home (16.9 ± 7.2 versus 13.6 ± 7.2) and the difference was significant (p < 0.05). Non-Latino white participants had a higher probability of being in the <80% median income group (relatively higher income) than either the black or Latino participants (49% for non-Latino white, 25% for Latino, and 23% for black participants); with a significant difference between non-Latino white and black participants (p < 0.05). The two income groups (<80% but >50% median and <50% median) did not vary significantly based on the gender of the asthmatic child, steroid use, asthma diagnosis, receipt of an asthma action plan, report of cough, wheeze or shortness of breath, ACT score, presence of pets, and reported smoking.

DISCUSSION

This study found that asthmatic children from low-income black and Latino families that enrolled in a healthy homes study had more areas of home safety and maintenance concerns than non-Latino whites families recruited from the same region. Housing has long been a marker of socioeconomic status and has been, in the United States, a mechanism for segregating communities based on income and race. This has produced concentrated poverty and perpetuated the downward spiral of housing conditions and community infrastructure in certain areas of nearly all cities.21 Communities of low socioeconomic status tend to have a disproportionate number of minority families. Additionally, these communities also tend to have low quality housing that relates to increases in many health conditions, including anxiety, depression, asthma, heart disease, and obesity.22 Many of these conditions are comorbid with one another. In a body mass index study of mostly black and Latino participants classified into underweight, normal, overweight, and obese, the obese body mass index percentile category was significantly associated with a diagnosis of asthma (p < 0.001).23 Minority populations are frequently isolated from the best areas of a city and located near the pollution of industrial facilities or transportation corridors. The housing in these communities tends to be dilapidated and thus contributes to multiple health disparities.24

The condition of urban housing and minority status are well-documented factors that relate children's health disparities to the built environment.25 Studies have suggested that improving living conditions in cities offers great promise for reducing health disparities and improving the quality of life and well-being of children.26 The relation of damp indoor spaces to respiratory disease has long been recognized.27,28 With recent understandings of the innate immune system components the serendipitous interaction of many types of biocontaminants in damp indoor environments, including molds, is becoming more fully understood.29,30 In this context, the relationship among damp environments, poor housing, and asthma is becoming appreciated.31 Studies combining weatherization and healthy home interventions with asthma education are beginning to significantly improve childhood asthma control32 and lower health-care costs.33

In the current study, the number of minority participants who enrolled was expected and the dropout rates, although high, were not unusual. The study screened a large number of potential participants and only a few either met the criteria for enrollment or elected to participate. Criteria for enrollment included an asthmatic child residing in the home and certain income restrictions. Income restriction to <80% of median income for the area and ability to document income by tax records or paycheck receipts played a large role in the number of screening failures. The time necessary to bring the participant child in for screening and attending several home visits and educational sessions was likely the largest factor for eligible families choosing not to participate (anecdotal). There was also considerable attrition because of failure to meet appointments, unplanned relocation, and lost communication mostly related to economic circumstances.

CMH is an inner city hospital and the study was confined to the urban regions of Kansas City, MO, and Kansas City, KS. In addition, CMH provides care without regard for ability to pay and has a historic reputation of service to low-income families in the metropolitan area. It is also the largest provider of Medicaid services to the pediatric population in the Kansas City metropolitan area. Because of large participation by Latino families, the consent form and other educational materials were available in Spanish and English. CMH also provided medical translators for clinical evaluation of participants and some members of the research team are native Spanish speakers.

The study was limited by the acknowledged strengths and weaknesses of using self-identification for minority status. Throughout the study minority status was assigned by self-identification of participating individuals. Additionally, participants were allowed to identify as more than one racial/ethnic group. Although not a perfect method, it is frequently used and historically viable. The U.S. Census allows people to self-identify and beginning in 2000, the U.S. Census has allowed individuals to self-identify as more than one racial/ethnic group.34 Ethnicity reflects self-identification with cultural traditions that provide personal meaning and boundaries among groups.35 Although this self-identification may not be fixed and is formed and transformed in relation to representation to the external audience, it is the best practical method for determination of race/ethnicity. The study is also limited by its cross-sectional design; we can not determine causality and do not know if asthma was present in children before living in these homes.

Participant homes were not unusual to the area. Housing in the Kansas City metropolitan area is typical for the midwestern United States. Most homes in the study were single-family homes, with a basement and forced air heating and cooling. Open flame gas stoves are a common method of cooking in the area and many participants had gas stoves. Repairing or installing proper kitchen ventilation was among the remediations offered by the study. Some of the participant homes were solidly built and in good repair whereas others were small, poorly constructed homes cobbled together by families of very limited means. The age of homes in the study varied widely and did not seem to be a factor. Latino participants typically lived in older housing, and individuals in the “other” group typically lived in newer housing. The mean housing age varied by 15 years among groups and was not significantly different for minority groups. Maintenance concerns were found in all housing types regardless of age. Home ownership percentage was greatest among non-Latino white and Latino participants and both groups were significantly different from black participants. Previous studies have indicated that Latino families place strong value on home ownership, with one study reporting that Latino families in Los Angeles are significantly more likely to be in housing-induced poverty than black families.36

The overall average age of the study participants did not vary significantly among groups. Because the age of participants was restricted, the mean age for participants was anticipated. Additionally, the male-to-female ratio of study participants was normal for the ages of asthmatic children seen in the Midwest.37

The most significant finding was that black and Latino families had more maintenance concerns in their homes than non-Latino white participants. There are many possibilities for the differences in the numbers of maintenance concerns in black and Latino homes in our study. The most obvious possibility is the difference in income. Individuals with increased income typically have more resources available to repair their homes. Additional reasons may be education and knowledge concerning home maintenance. Neighborhood peer pressure may also play a role in home upkeep and maintenance. Individuals segregated into areas where poorer home conditions are the norm may have less motivation for home maintenance versus individuals living in areas where poorly maintained homes would strongly stand out from the norm.

The finding that black participants had increased steroid use was unexpected. Reasons for increased steroid use in our black participants could be related to the reported lower vitamin D levels in this group38,39 and the observation that steroid use in asthmatic subjects is inversely proportional to vitamin D levels.40 Other reported symptom scores for groups in the study were similar. This study was designed not only to examine asthma and housing but also to provide help for the most severe asthmatic patients. In addition to education and home assessments, funds were also available for remediation of home safety and air quality issues. Asthmatic subjects in this study were selected because of their significant level of disease and were similar in symptoms. Overall symptom reports for all groups were very high. Small differences between racial/ethnic groups were insignificant compared with the high baseline.

It was unexpected that black participants would have significantly lower ACT scores than the non-Latino white group. However, in studies of asthma perception of differing groups, it has been reported that black subjects view their asthma differently. Black subjects were less likely to report nocturnal awakenings or complain of dyspnea than non-Latino white subjects. Also, many black people do not report asthma-related nocturnal symptoms, which are particularly important in the ACT.41,42

Income guidelines are not only reflected in the results of the study but may be driving the results. Participation in this study was restricted to persons with incomes <80% of the median for the area and stratified into two groups: (1) < 80% of area median (two-thirds of participants) and (2) <50% of area median (one-third of participants). There were disproportionately larger numbers of black and Latino individuals in the <50% median income group. This correlates with the finding that their homes contained more maintenance concerns than the homes of non-Latino white families. This is also consistent with the observation that the home age is also related to maintenance concerns. A possible reason for the few disparities in the health indicators for asthma (Table 3) could be that to qualify for this level of the study, children had more severe/uncontrolled asthma. Also, most of the children had their asthma treated in the CMH system without regard to ability to pay and therefore received a uniform level of assessment and treatment. Children not receiving care because of a parental misconception that they would not be seen for financial reasons were not likely to be captured in this recruitment.

The use of income for enrollment into the study was a requirement set by the funding agency (the U.S. Department of HUD). The enrollment of large numbers of racial/ethnic minority children in the study was more likely a result of the overall patient population of CMH and its associated clinics than the income guidelines imposed by HUD.

We did find significantly more black and Latino study participants were in the lower-income group. Specific reasons for the income disparities seen between the minority groups and the non-Latino white group in the study are not obvious. Possible reasons include historically lower wealth levels in these groups and recent immigrant status of several families. Regardless of the reasons, lower wealth and socioeconomic status is related to stress and asthma. Stress is thought to influence immune function through sympathetic, parasympathetic, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis mechanisms.43 There is increasing evidence linking psychosocial stress to asthma and atopic disorders.44 A psychosocial stress model has been developed as a mechanism responsible for health disparities among economic and racial/ethnic groups. A concept has been put forward suggesting the social contexts in which children are raised is just as detrimental to their development as physical environmental factors are.45 It is also possible that epigenetic programming may cause long-lasting alterations in stress-induced phenotypic plasticity related to asthma risk.46 There are frequent reports that nonwhite children living in poverty and residing in urban areas have a significantly higher risk of asthma than white children.46 National surveys indicate asthma risk is particularly high among children with disadvantages in both racial status and socioeconomic status.47 Reviews indicate low-income children are more likely to consume polluted air and water, live in lower quality housing, reside in more dangerous neighborhoods, and have poorer quality child care and educational opportunities.48,49 This study reinforces evidence in its findings that racial/ethnic minorities have more areas of home safety and maintenance concerns than non-Latino white families recruited from the same region.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the members of the CMH Center for Environmental Health for the vast amount of work involved in collecting data. Their membership includes Jay Portnoy, M.D.; Jennifer Lowry, M.D.; Kevin Kennedy, M.P.H.; Erica Forrest, R.T.; Tanisha Webb, R.T.; Luke Gard E.H.S.; Ryan Allenbrand, M.S.; and Mohammed Mubeen, M.S.

Footnotes

Funded by Children's Mercy Hospital, by a Healthy Homes Demonstration Project Award from Housing and Urban Development and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20 MD004805: PI Daley) and by a Clinical and Translational Science Award grant from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences awarded to the University of Kansas Medical Center for Frontiers: The Heartland Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (KL2TR000119); CM Pacheco was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute and the Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities (U54 CA154253)

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare pertaining to this article

REFERENCES

- 1. Eggleston PA. The environment and asthma in US inner cities. Chest Nov 132(suppl):782S–788S, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rauh VA, Chew GR, Garfinkel RS. Deteriorated housing contributes to high cockroach allergen levels in inner-city households. Environ Health Perspect 10(suppl 2):323–327, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krieger JK, Takaro TK, Allen C, et al. The Seattle-King County healthy homes project: Implementation of a comprehensive approach to improving indoor environmental quality for low-income children with asthma. Environ Health Perspect 110(suppl 2):311–322, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bryant-Stephens T. Asthma disparities in urban environments. J Allergy Clin Immunol 123:1199–1206, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miller WD, Pollack CE, Williams DR. Healthy homes and communities: Putting the pieces together. Am J Prev Med Jan 40(suppl 1):S48–S57, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morello-Frosch R, Zuk M, Jerrett M, et al. Understanding the cumulative impacts of inequalities in environmental health: Implications for policy. Health Aff (Millwood) 30:879–887, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Malik HU, Kumar K, Frieri M. Minimal difference in the prevalence of asthma in the urban and rural environment. Clin Med Insights Pediatr 6:33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. Housing challenges. In The State of the Nation's Housing. Fernald M. (Ed). Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 26–31, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matsui EC. Environmental exposures and asthma morbidity in children living in urban neighborhoods. Allergy 69:553–558, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sahiner UM, Buyuktiryaki AB, Yavuz ST, et al. The spectrum of aeroallergen sensitization in children diagnosed with asthma during first 2 years of life. Allergy Asthma Proc 34:356–361, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Northridge J, Ramirez OF, Stingone JA, Claudio L. The role of housing type and housing quality in urban children with asthma. J Urban Health 87:211–224, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bryant-Stephens T, Kurian C, Guo R, Zhao H. Impact of a household environmental intervention delivered by lay health workers on asthma symptom control in urban, disadvantaged children with asthma. Am J Public Health 99(suppl 3):S657–S665, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matsui EC, Hansel NN, Aloe C, et al. Indoor pollutant exposures modify the effect of airborne endotoxin on asthma in urban children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188:1210–1215, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lanphear BP, Aligne CA, Auinger P, et al. Residential exposures associated with asthma in US children. Pediatrics 107:505–511, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Diette GB, Hansel NN, Buckley TJ, et al. Home indoor pollutant exposures among inner-city children with and without asthma. Environ Health Perspect 115:1665–1669, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, et al. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. NCHS data brief, no 94. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db94.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Diette GB, Rand C. The contributing role of health-care communication to health disparities for minority patients with asthma. Chest 132(suppl):802S–809S, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Olden K, White SL. Health-related disparities: Influence of environmental factors. Med Clin North Am 89:721–738, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teach SJ, Crain EF, Quint DM, et al. Indoor environmental exposures among children with asthma seen in an urban emergency department. Pediatrics 117:S152–S158, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Portnoy, Flappan S, Barnes C. A standardized procedure for evaluation of the indoor environment. Aerobiologia 17:43–48, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fry R, Taylor P. Rising income and residential inequality. In The rise of residential segregation by income. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 8–9, 2012. www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2012/08/Rise-of-Residential-Income-Segregation-2012.2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22. Srinivasan S, O'Fallon LR, Dearry A. Creating healthy communities, healthy homes, healthy people: Initiating a research agenda on the built environment and public health. Am J Public Health Sep 93:1446–1450, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malik H, Kumar K, Foge J, Frieri M. Obesity is associated with asthma in patients from an underserved low physician to patient ratio area in a New York pediatric emergency department. Internet J Pulm Med 13:1, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee M, Rubin V. Incorporating principles of equity. In The Impact of the Built Environment on Community Health: The State of Current Practice and Next Steps for a Growing Movement. Los Angeles, CA: PolicyLink, 37–40, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bashir SA. Home is where the harm is: Inadequate housing as a public health crisis. Am J Public Health 92:733–738, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vlahov D, Freudenberg N, Proietti F, et al. Urban as a determinant of health. J Urban Health 84(suppl):i16–i26, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brunekreef B, Dockery DW, Speizer FE, et al. Home dampness and respiratory morbidity in children. Am Rev Respir Dis 140:1363–1367, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peat JK, Dickerson J, Li J. Effects of damp and mould in the home on respiratory health: A review of the literature. Allergy 53:120–128, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thrasher JD, Crawley S. The biocontaminants and complexity of damp indoor spaces: More than what meets the eyes. Toxicol Ind Health 25:583–615, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Van Dyken SJ, Garcia D, Porter P, et al. Fungal chitin from asthma-associated home environments induces eosinophilic lung infiltration. J Immunol 187:2261–2267, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. National Research Council. Indoor dampness and asthma. In Clearing the Air: Asthma and Indoor Air Exposures. Washington D.C.: The National Academies Press, 298–315, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Breysse J, Dixon S, Gregory J, et al. Effect of weatherization combined with community health worker in-home education on asthma control. J Am J Public Health 104:e57–e64, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Turcotte DA, Alker H, Chaves E, et al. Healthy homes: in-home environmental asthma intervention in a diverse urban community. Am J Public Health 104:665–671, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hirschman C, Alba R, Farley R. The meaning and measurement of race in the US census: Glimpses into the future. Demography 37:361–393, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Karlsen S, Nazroo JY, Stephenson R. Ethnicity, environment and health: Putting ethnic inequalities in health in their place. Soc Sci Med 55:1647–1661, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McConnell ED. House poor in Los Angeles: Examining patterns of housing-induced poverty by race, nativity, and legal status. Hous Policy Debate 22:605–631, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yun HD, Knoebel E, Fenta Y, et al. Asthma and proinflammatory conditions: A population-based retrospective matched cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc 87:953–960, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Paul G, Brehm JM, Alcorn JF, et al. Vitamin D and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185:124–132, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Frieri M. The role of vitamin D in asthmatic children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 11:1–3, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Searing DA, Zhang Y, Murphy JR, et al. Decreased serum vitamin D levels in children with asthma are associated with increased corticosteroid use. J Allergy Clin Immunol 125:995–1000, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Trochtenberg DS, BeLue R. Descriptors and perception of dyspnea in African-American asthmatics. J Asthma 44:811–815, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Trochtenberg DS, BeLue R, Piphus S, Washington N. Differing reports of asthma symptoms in African Americans and Caucasians. J Asthma 45:165–170, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wright RJ. Stress-related programming of autonomic imbalance: Role in allergy and asthma. Chem Immunol Allergy 98:32–47, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wright RJ. Epidemiology of stress and asthma: From constricting communities and fragile families to epigenetics. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 31:19–39, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wright RJ. Moving towards making social toxins mainstream in children's environmental health. Curr Opin Pediatr 21:222–229, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Williams DR, Sternthal M, Wright RJ. Social determinants: Taking the social context of asthma seriously. Pediatrics 123(suppl 3):S174–S184, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smith LA, Hatcher-Ross JL, Wertheimer R, Kahn RS. Rethinking race/ethnicity, income, and childhood asthma: Racial/ethnic disparities concentrated among the very poor. Public Health Rep 120:109–116, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Evans GW. The environment of childhood poverty. Am Psychol 59:77–92, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Evans GW, Marcynyszyn LA. Environmental justice, cumulative environmental risk, and health among low- and middle-income children in upstate New York. Am J Public Health 94:1942–1944, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]