Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To determine the prevalence and characteristics of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) among first grade students (6- to 7-year-olds) in a representative Midwestern US community.

METHODS:

From a consented sample of 70.5% of all first graders enrolled in public and private schools, an oversample of small children (≤25th percentile on height, weight, and head circumference) and randomly selected control candidates were examined for physical growth, development, dysmorphology, cognition, and behavior. The children’s mothers were interviewed for maternal risk.

RESULTS:

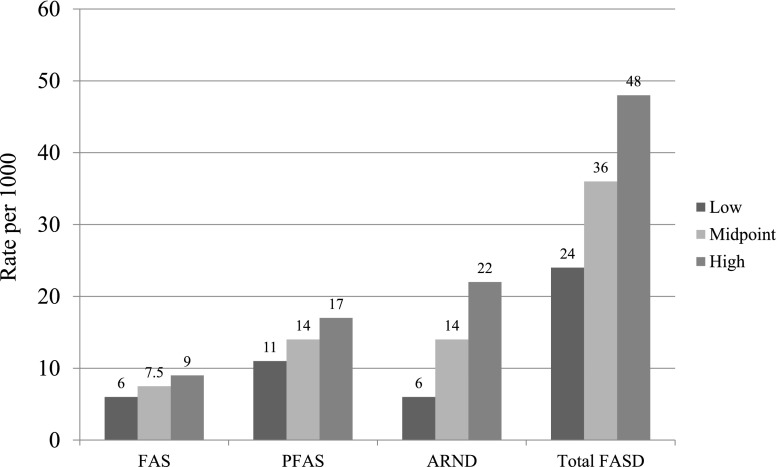

Total dysmorphology scores differentiate significantly fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) and partial FAS (PFAS) from one another and from unexposed controls. Alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND) is not as clearly differentiated from controls. Children who had FASD performed, on average, significantly worse on 7 cognitive and behavioral tests and measures. The most predictive maternal risk variables in this community are late recognition of pregnancy, quantity of alcoholic drinks consumed 3 months before pregnancy, and quantity of drinking reported for the index child’s father. From the final multidisciplinary case findings, 3 techniques were used to estimate prevalence. FAS in this community likely ranges from 6 to 9 per 1000 children (midpoint, 7.5), PFAS from 11 to 17 per 1000 children (midpoint, 14), and the total rate of FASD is estimated at 24 to 48 per 1000 children, or 2.4% to 4.8% (midpoint, 3.6%).

CONCLUSIONS:

Children who have FASD are more prevalent among first graders in this Midwestern city than predicted by previous, popular estimates.

Keywords: fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, alcohol use and abuse, women, prenatal alcohol use, prevalence, children with FASD

What’s Known on This Subject:

Most studies of fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) prevalence in the general population of the United States have been carried out using passive methods (surveillance or clinic-based studies), which underestimate rates of FASD.

What This Study Adds:

Using active case ascertainment methods among children in a representative middle class community, rates of fetal alcohol syndrome and total FASD are found to be substantially higher than most often cited estimates for the general US population.

Determining the prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) in a general population has proved to be an elusive task. Since the diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) was first described in 1973,1 surveillance systems, prenatal clinic-based studies, and special referral clinics have proven inadequate for determining the prevalence of FAS or FASD. The often cited estimates for general populations are believed to be underestimates; yet very high rates have been found in certain substrate populations.2,3 Rates from high-risk subgroups cannot be extrapolated accurately to general populations.4,5

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has estimated that FAS occurs at a rate of 0.2 to 1.5 per 1000 children,6,7 and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) estimates are 0.5 to 3.0 per 1000 children.8 More current estimates of the prevalence of FAS in the US general population range from 0.2 to 7 per 1000 children,5 and 2% to 5% for the entire continuum of FASD.5,9

One approach used successfully to determine the minimal prevalence of FASD in communities in South Africa,10–14 Italy,15,16 and Croatia17,18 uses active case ascertainment in schools. Providing targeted physical examinations and cognitive/behavioral testing to primary school children19–22 and interviewing their mothers23–25 can be effective for studying FASD prevalence and characteristics.

The Study Community

This study examined the prevalence and characteristics of FASD among first grade children in a representative Midwestern US city. Maternal risk factors for FASD were also explored. A total of 160 000 persons reside in the study community, among whom 87% are white. The residents are predominately middle class, with a per capita income of $28 000 and median household income of $51 800; 11% are below the poverty level. These indicators and others are virtually identical to US averages, except that US norms indicate that 14% of the general population is below the poverty level and reflect more racial diversity than the study community.26 Per capita alcohol consumption in this state was 9.9 L of ethanol per year in 2009, 14% higher than the US average of 8.7 L,27 but this county had an alcohol-related mortality index 27% less than the state as a whole.28 The United Health Foundation29 overall health ranking of this state is between 20 and 25 of 50 states. Data from the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System ranks the general health status of this county at 3.6 (above average) of a possible 5, and cites smoking at the US average.30 In 2011, CDC data reported that 54% of females there consumed alcohol in the past 30 days, slightly higher than the US average.31

Methods

Protocols and consent forms were approved by The University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Human Research Review Committee, and the University of North Carolina. Active consents for children and mothers to participate were obtained.

IOM diagnostic guidelines for FASD8 were used. Classification of children is based on (1) physical growth and dysmorphology; (2) cognitive assessments administered by school psychologists and behavioral assessments by teachers; and (3) interviews on maternal risk factors. Other malformation syndromes were ruled out, and final diagnoses made for each child in a data-driven case conference.32

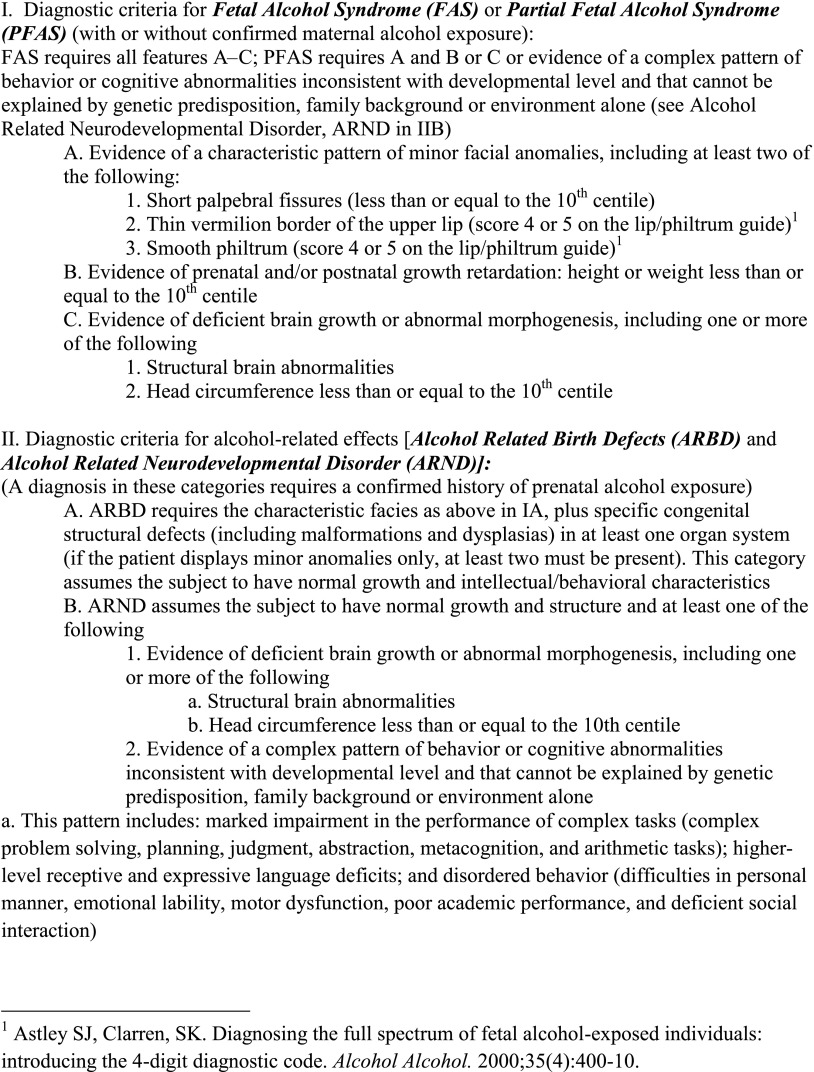

The continuum of FASD comprises 4 diagnoses: FAS, partial fetal alcohol syndrome (PFAS), alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND), and alcohol-related birth defects.8 Each of the diagnostic categories (Fig 1) was considered in this study. The diagnosis of FAS without a confirmed history of alcohol exposure is permitted by the original IOM criteria,8 and revised criteria32 permit diagnosis of PFAS with other evidence of prenatal drinking. Many women underreport drinking during pregnancy,24,33–35 yet the diagnosis is rarely made without direct maternal reports of alcohol use before pregnancy recognition and/or in the first trimester, or collateral reports. An ARND diagnosis requires direct confirmation of prenatal alcohol use in the index pregnancy.

FIGURE 1.

Diagnostic guidelines for specific FASDs, according to the Institute of Medicine, as clarified by Hoyme et al 2005.

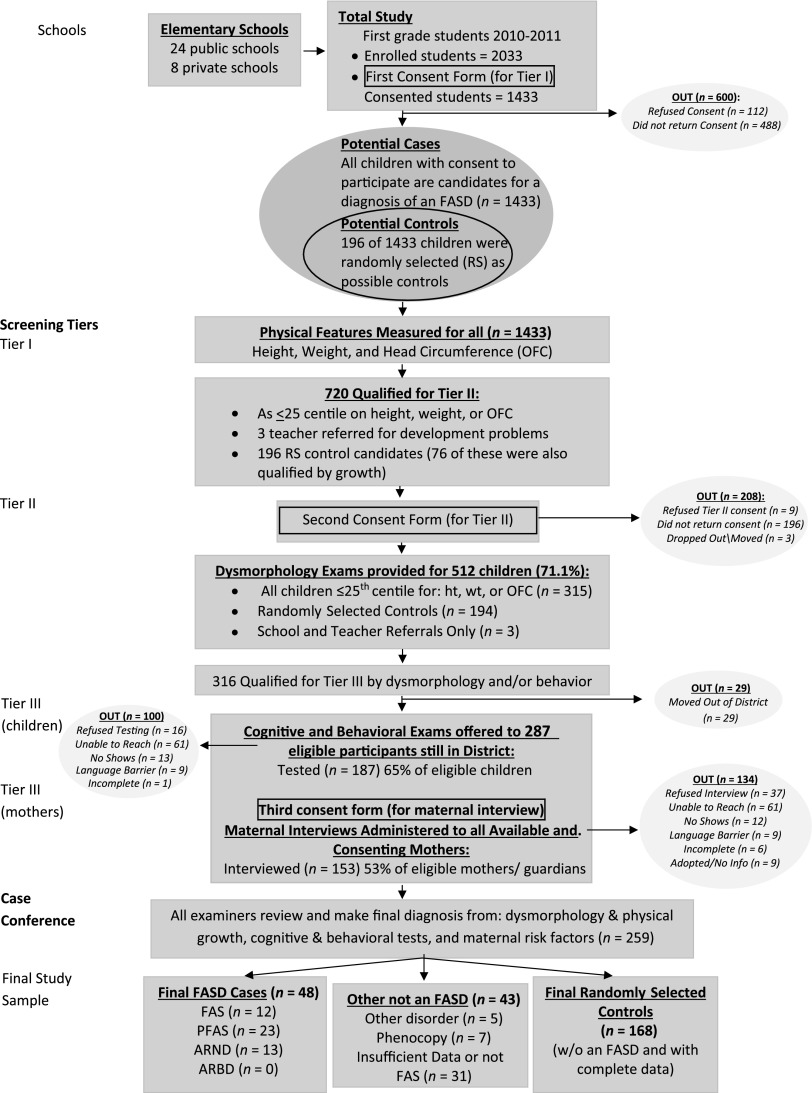

Sampling of First Grade Children: Oversampling Small Children and Random Selection

Because particular dysmorphic features have proven to most clearly identify children exposed to alcohol prenatally,1,32,34,36 oversampling of small children was undertaken to identify as many of the most dysmorphic children in the population as possible; additionally a random sample of children was drawn to provide candidates for representative, normal controls. All children enrolled in first grade (n = 2033) in all 32 public and private schools were measured for height, weight, and head circumference (OFC) at the beginning of the school year. Consent forms were then sent to the parents/guardians of all first grade students; 70.5% provided consent to participate. Consented children entered the study simultaneously via oversampling for growth deficiency and/or small OFC and/or random selection as a potential normal control. A few teacher referrals of children who had suspected developmental issues were also accepted in the study (Fig 2). Candidates for the comparison/control group were 250 students whose numbers were randomly selected from school roles; 196 consented to participate. The final control sample was 168 (see Fig 2), as 19 of the randomly selected children ultimately received a diagnosis of a FASD or another disorder, and 9 had incomplete data. Identical examinations and testing were performed on all potential subjects and controls (Fig 2).

FIGURE 2.

Sampling methodology for prevalence of FASD in a Midwestern city.

Study Procedures: Screening in Tiers I and II

In Tier I, the schools released the consented children’s identified height, weight, and OFC measurements to study personnel along with school rolls. Any consented child ≤25th percentile on OFC or height or weight and all children randomly selected as control candidates were included in Tier II physical examinations (Fig 2). Seventy-six of the randomly selected children also qualified on 1 or more of the growth measures. In-school examinations were then scheduled.

Four teams, each headed by a pediatric dysmorphologist, provided brief, structured examinations including assessment of growth, anthropometric measurements, and minor anomalies of the craniofacies and hands. Each child was assessed for the qualifying cardinal features of FASD and other minor anomalies and then assigned a “dysmorphology score,” an objective quantification of growth deficiency and minor anomalies. (Although not used in the final assignment of FASD diagnoses, the score is a useful research tool, correlating well with maternal drinking and learning/behavior difficulties in affected children.)12,34 Examiners were blinded from previous knowledge of children and mothers. Inter-rater reliability in previous studies has been good.10,13,32

After reviewing dysmorphology findings for each child, a preliminary diagnosis was assigned by the dysmorphologist: (1) not-FASD, (2) diagnosis deferred, rule out a specific FASD or a related disorder, or (3) probable FAS or PFAS.

Study Procedures: Tier III — Child Testing and Maternal Risk Factor Questionnaires

Development and behavior were assessed by blinded school psychologists with the Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration37; the Differential Ability Scales, Second Edition38; and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales – Parent/Caregiver Rating Form and Teacher Rating Form.39

All consenting mothers of children in Tier III were administered interviews by project staff. Sequencing of questions was to maximize accurate reporting of general health, reproduction, nutrition, alcohol use, socioeconomic status (SES), and maternal height, weight, and OFC. Drinking questions used a timeline, follow-back sequence,40,41 and Vessels alcohol product methodology for accurate calibration of standard alcohol units.42–44 Current alcohol consumption for the week preceding the interview was embedded into the nutrition questions45 to aid accurate calibration of drinking quantity, frequency, and timing of alcohol use before and during the index pregnancies.10,11,23–25,33 Retrospective reports of alcohol use have been found to be superior to concurrent reports, but alcohol use has still been found to be frequently underreported in studies such as this.33,46–48

Maternal risk data were gathered for 153 women (Fig 2). Data presented focus on confirmation of maternal drinking for diagnosis and general risk factors in the study community. Drinking during pregnancy was confirmed with direct reports of a minimum of 7 drinks or more per week, or a binge of 3 or more drinks during any trimester or before pregnancy recognition in the third week of gestation or later. Collateral reports were also used for confirmation in 7 cases, 5 of which were from the child’s father. Detailed maternal risk factor information for FASD in other populations has been reported elsewhere.12,24,25,34,46

Final Diagnoses Made in Case Conferences

After completion of data collection, final diagnoses for each child were made in a confidential, structured, multidisciplinary case conference. The examiners, testers, and maternal interviewers each provided an oral and written summary of data and assessments for their domain for each child, and 2-dimensional photographs of the children were reviewed. After discussion of specific findings, final diagnoses were made by the examining dysmorphologist(s) after the team applied the IOM diagnostic criteria (Fig 1).

Data Analysis

Data analyses were performed with Excel49 and SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation).50 Child physical, cognitive/behavioral, and maternal risk findings were compared across diagnostic groups using χ2 for categorical variables and 1-way analysis of variance for interval level variables.51 With statistically significant ANOVAs, post hoc analyses were performed using Dunnett’s correction pairwise comparisons (α = 0.05).

Estimating FASD Prevalence Using 3 Techniques

Prevalence rates were calculated from the total number of children in the consented population receiving each diagnosis within the FASD continuum and 2 different denominators: (a) total students enrolled in the first grade classes (n = 2033), and (b) total children consented into the study (n = 1433). Because of alcohol-induced growth deficiency, oversampling of small 6- and 7-year-old children who had dysmorphology examinations should capture a majority of all FAS and PFAS cases.32 And with random selection for potential controls, many ARND cases are likely identified.

The second estimation of prevalence rates used the number and proportion of cases found among the children who were randomly selected as potential control/comparison children. The proportion of each FASD diagnostic category to the total selected was calculated and then projected to rates per 1000 as explained in detail in the results section for Table 5.

The third technique used the proportion of randomly selected children with each FASD diagnosis projected to the un-consented population (n = 600) to determine estimated cases of FASD in the un-examined group. These estimated cases were then added to the cases identified by technique 1 methods and rates computed as in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Prevalence Rates (per 1000) of Individual Diagnoses Within the FASD and Total FASD for First Grade Children in the Midwestern City: Prevalence Using 3 Techniques

| Diagnosis | 1. Oversample of children ≤25th percentile on height, weight, or OFC | 2. Randomly Selected Children Only (n = 196) | 3. Estimated rate for all students combining results from techniques 1 and 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Rate per all children enrolled in first grade (n = 2033)a | Rate for all children with consent for study (n = 1433)b | Midpoint | n | Rate of FASD cases from random samplec | 95% CI | Estimated rate of FASDd | 95% CI | |

| FAS | 12 | 5.9 | 8.4 | 7.1 | 2 | 10.2 | 0.0–24.3 | 8.9 | 4.8–12.9 |

| PFAS | 23 | 11.3 | 16.1 | 13.7 | 4 | 20.4 | 0.06–40.2 | 17.2 | 11.6–22.9 |

| FAS and PFAS combined | 35 | 17.2 | 24.2 | 20.8 | 6 | 30.6 | 6.5–54.7 | 26.1 | 19.1–32.9 |

| ARND | 13 | 6.4 | 9.1 | 7.7 | 10 | 51.0 | 20.2–81.8 | 21.6 | 15.3–27.9 |

| Total FASD | 48 | 23.6 | 33.5 | 28.6 | 16 | 81.6 | 43.3–119.9 | 47.7 | 38.5–56.9 |

Rate per 1000 children based on the enrolled sample, denominator = 2033.

Rate per 1000 children based on the sample screened, denominator = 1433.

Rate per 1000 children based on the randomly selected children only, denominator = 196.

Rate per 1000 children calculated from FASD cases diagnosed in consented sample added to the estimated cases in the non-consented sample using the proportional diagnostic distribution of FASD cases from the randomly selected children.

Results

Child Demographic and Physical Variables

Neither age nor gender distinction by gender ratio was found across diagnostic categories or controls (see Table 1). In addition to the demographic variables in Table 1, racial composition was examined. The overall sample is white (76%), black (7.0%), Asian (4.3%), Native American (3.7%), mixed race (0.8%), and Hispanic (8.2%). The overall racial make-up of all children diagnosed with an FASD does not differ significantly, and when similar individual comparisons are made for each diagnosis (FAS, PFAS, ARND, and not FASD), there are no significant differences by race or ethnicity.

TABLE 1.

Child Demographic, Growth, and Cardinal FASD Dysmorphology Variables in the Midwestern City by Diagnosis

| Physical variable | Wholea Sample | FAS | PFAS | ARND | Controlsb | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 512 | n = 12 | n = 23 | n = 13 | n = 168 | ||

| % OR | % OR | % OR | % OR | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Gender, % male | 51.8 | 50.0 | 47.8 | 53.8 | 56.0 | .884 |

| Age, mo | 82.9 (5.2) | 83.5 (6.5) | 83.7 (5.3) | 84.8 (3.2) | 82.9 (5.3) | .610 |

| Height percentile | 43.3 (28.9) | 6.8 (6.0) | 30.0 (30.0) | 47.9 (33.6) | 57.1 (27.8) | <.001c |

| Weight percentile | 46.7 (29.4) | 10.2 (8.9) | 32.4 (27.4) | 44.1 (32.5) | 60.3 (27.3) | <.001c |

| OFC percentile | 47.2 (30.4) | 3.8 (3.1) | 34.8 (23.8) | 43.8 (32.7) | 65.7 (27.1) | <.001c |

| Average BMI | 15.4 (0.1) | 15.4 (0.1) | 15.4 (0.1) | 15.5 (0.1) | 15.4 (0.1) | .721 |

| BMI percentile | 51.7 (29.3) | 33.5 (28.8) | 43.1 (27.7) | 44.5 (31.8) | 60.0 (27.5) | .008d |

| PFL percentile | — | 17.8 (19.5) | 12.1 (12.1) | 31.9 (10.1) | 29.1 (16.1) | <.001e |

| Smooth philtrum, % | — | 91.7 | 91.3 | 7.7 | 11.9 | <.001 |

| Narrow vermilion border of the upper lip, % | — | 83.3 | 87.0 | 23.1 | 19.0 | <.001 |

| Total dysmorphology score | — | 16.7 (2.4) | 12.4 (3.5) | 6.0 (2.9) | 4.2 (2.9) | <.001f |

PFL, palpebral fissure length; —, data not collected for the whole sample on these variables.

Statistical tests compare only individual diagnostic groups and controls and not the whole sample values.

Two controls were reported as alcohol-exposed prenatally.

Post hoc analysis indicates significant difference between FAS and PFAS, FAS and ANRD, FAS and controls, and PFAS and controls.

Post hoc analysis indicates significant difference between FAS and PFAS.

Post hoc analysis indicates significant difference between FAS and PFAS, PFAS and ARND, and PFAS and controls.

Post hoc analysis indicates significant difference between FAS and PFAS, FAS and ARND, FAS and controls, PFAS and ARND, and PFAS and controls.

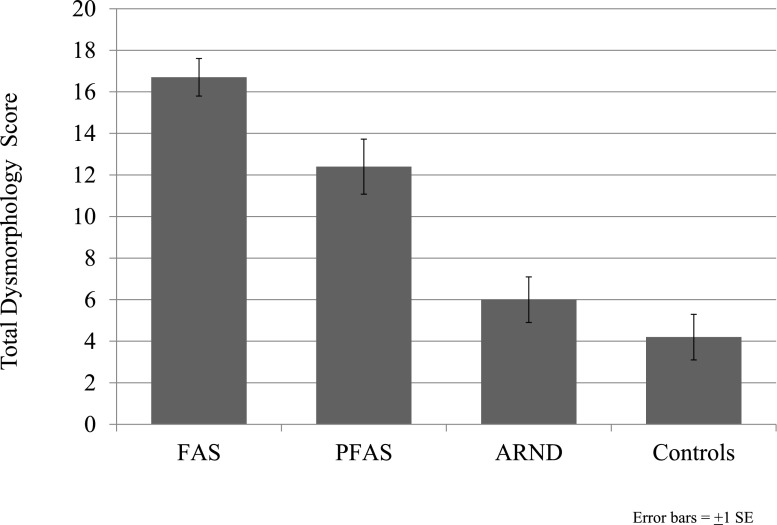

Virtually all key physical variables (see Table 1) differed significantly across diagnostic categories. Child height, weight, and OFC centiles were significantly different among diagnostic groups, with post hoc analyses indicating significant pairwise differences between each of the groups except ARND versus controls. Children who had a FAS diagnosis were shorter, lighter, and had smaller heads than all others. BMI centile differed significantly by diagnosis, with the FAS group having the lowest BMI, and in ascending order PFAS, ARND, and controls. Palpebral fissure length centile differed significantly by child diagnosis, with post hoc analyses indicating significant differences among the PFAS, ARND, and controls. A significantly higher frequency of smooth philtrum exists among children who have FAS than those who have PFAS, ARND, and controls. A narrow vermilion border of the upper lip was significantly different between all children who had a FASD and controls. Finally, all groups differed significantly by mean total dysmorphology score (Fig 3). The FAS group had the highest average, followed by PFAS, ARND, and controls, and the total dysmorphology score significantly discriminated the FAS and PFAS groups from every other group.

FIGURE 3.

Total dysmorphology scores by diagnostic category for a Midwestern city study.

Minor Dysmorphic Features

The frequency of minor anomalies not specifically included in the IOM diagnostic criteria, but in the total dysmorphology score, are presented in Table 2. Short inner canthal distance, inter-pupillary distance, clinodactyly and camptodactyly all differed significantly by diagnosis (see Table 2). Children who had a FASD are more likely to have a hypoplastic midface as measured by clinical observation, and they are also likely to have lower measurements on maxillary and mandibular arcs. More clinodactyly and camptodactyly exist among children who had FASD than controls (see Table 2). Epicanthal folds were more frequent among children who had FASD, but not significantly different.

TABLE 2.

Other Minor Anomalies of Study Children in the Midwestern City by Diagnosis

| Minor Anomaly Variable | FAS | PFAS | ARND | Controlsa | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 12 | n = 23 | n = 13 | n = 162 | ||

| % OR | % OR | % OR | % OR | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Maxillary arc, cm | 23.3 (1.2) | 23.9 (1.0) | 24.3 (1.1) | 25.0 (1.5) | <.001 |

| Mandibular arc, cm | 23.8 (1.3) | 24.9 (1.3) | 25.1 (1.3) | 25.9 (1.3) | <.001 |

| ICD percentile | 30.1 (20.4) | 44.7 (20.4) | 41.5 (19.1) | 55.5 (22.1) | <.001b |

| IPD percentile | 37.3 (17.4) | 37.3 (15.1) | 53.7 (25.0) | 59.5 (24.2) | <.001c |

| Hypoplastic midface, % | 58.3 | 52.2 | 53.8 | 26.8 | .005 |

| Epicanthic folds, % | 41.7 | 30.4 | 7.7 | 17.3 | .065 |

| Clinodactyly, % | 41.7 | 60.9 | 38.5 | 28.6 | .018 |

| Camptodactyly, % | 16.7 | 0.0 | 15.4 | 3.0 | .016 |

ICD, inner canthal distance; IPD, inter-pupillary distance.

Two controls reported as alcohol-exposed during pregnancy.

Dunnett’s C post hoc analysis shows differences between FAS and controls.

Dunnett’s C post hoc analysis shows differences between FAS and controls; PFAS and controls.

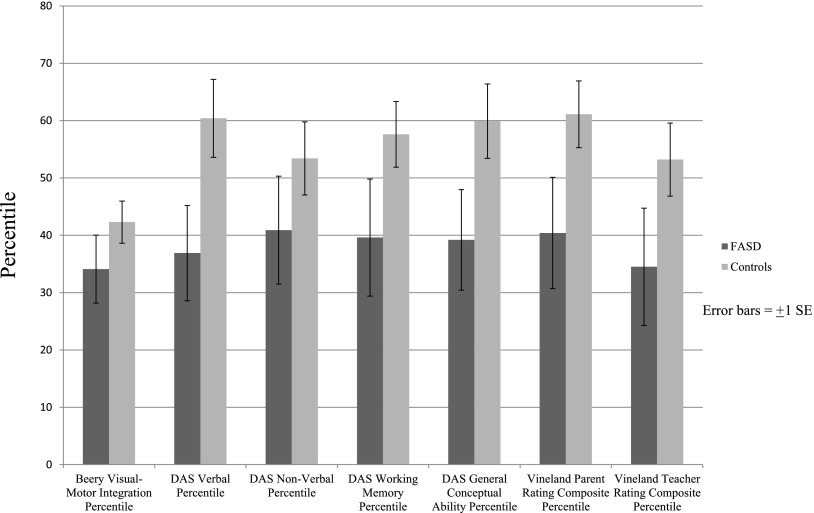

Child Cognitive and Behavioral Test Performance

Performance centiles on all cognitive and behavioral tests were significantly lower for children who had FASD than the controls (see Table 3 and Fig 4). The FASD group performed most poorly compared with the control group on verbal IQ, working memory, general and conceptual ability, and parent and teacher rating of adaptive behavior.

TABLE 3.

Child Cognitive and Behavioral Test Performance Centile by Diagnosis in the Midwestern City

| Test variable | FASD | Controls | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 36 | n = 98 | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Beery visual-motor integration percentile | 34.1 (15.7) | 42.3 (14.7) | .005 |

| DAS verbal percentile | 36.9 (22.0) | 60.4 (27.2) | <.001 |

| DAS nonverbal percentile | 40.9 (24.9) | 53.4 (25.5) | .013 |

| DAS working memory percentile | 39.6 (27.0) | 57.6 (22.9) | <.001 |

| DAS general conceptual ability percentile | 39.2 (23.2) | 59.9 (25.9) | <.001 |

| Vineland parent rating composite percentile | 40.4 (25.7) | 61.1 (23.3) | <.001 |

| Vineland teacher rating composite percentile | 34.5 (27.1) | 53.2 (25.5) | <.001 |

DAS, Differential Ability Scales.

FIGURE 4.

Child cognitive/behavioral test performance centiles by diagnosis in a Midwestern city.

Maternal Risk Factors

Mothers of children who had FASD reported first recognition of pregnancy (measured from the first day of last menstruation) further into gestation than did controls, and fewer health care provider visits during pregnancy, although the latter difference only approached significance. Mothers of children who had FASD reported consuming significantly more drinks per drinking day 3 months before pregnancy than did controls. Approaching significance in the data were that the FASD maternal group reported more first trimester alcohol consumption, were more likely to binge with 5 or more drinks, and reported more drinking days in the past 30 days than controls. Mothers of children who had FASD reported that their husbands/partners consumed significantly more drinks per drinking day during pregnancy, and more paternal binge drinking, although the latter variable only approached significance. Non-significant differences in common maternal risk variables are reported in Table 4, so that comparisons can be made for this US population with other populations where the traits are more commonly found.

TABLE 4.

Maternal Characteristics in the Midwestern City by Child Diagnostic Category

| Maternal Characteristic and Risk Indicator Variables | FASD | Controlsa | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 30 | n = 80 | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Maternal age at pregnancy, y | 30.0 (6.6) | 29.3 (5.9) | .578 |

| Maternal height, cm | 165.0 (7.6) | 166.1 (6.6) | .457 |

| Maternal weight, kg | 71.1 (23.0) | 78.7 (21.4) | .109 |

| Maternal OFC, cm | 54.5 (2.1) | 55.0 (1.5) | .260 |

| Maternal BMI | 26.5 (8.4) | 28.5 (7.9) | .252 |

| Number of weeks into the pregnancy that mother knew she was pregnant | 9.0 (8.4) | 4.9 (2.6) | .013 |

| Number of times mother saw health care provider during pregnancy | 10.6 (3.6) | 11.8 (1.4) | .100 |

| Index child’s birth order | 2.0 (0.9) | 2.0 (1.2) | .891 |

| Gravidity | 3.5 (1.9) | 3.2 (1.3) | .398 |

| Parity | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.0) | .503 |

| Highest grade mother completed | |||

| Below high school, % yes | 6.7 | 7.5 | .948 |

| High School, % yes | 43.3 | 40.0 | |

| College, % yes | 50.0 | 52.5 | |

| Estimated yearly income (household median in dollars) | 50 000 | 59 000 | .538 |

| Number of drinking days in the past 30 days (drinkers only) | 4.9 (5.7) | 3.0 (2.7) | .186 |

| Bingeing (3 drinks per occasion) in the past month, % yes | 33.3 | 25.0 | .403 |

| Bingeing (5 drinks per occasion) in the past month, % yes | 18.5 | 8.9 | .172 |

| Drinks per drinking day 3 months before mother’s pregnancy | 2.7 (1.5) | 1.4 (1.9) | .002 |

| First trimester: usual number of drinks per drinking day | 0.5 (1.4) | 0.1 (0.6) | .164 |

| Second trimester: usual number of drinks per drinking day | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.0 (0.1) | .241 |

| Third trimester: usual number of drinks per drinking day | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.1) | .409 |

| Number of days in the past 30 days that husband consumed 5+ drinks per drinking occasion | 2.8 (7.2) | 0.5 (1.0) | .192 |

| Usual number of drinks per drinking day consumed by mother’s husband during pregnancy | 4.0 (2.7) | 2.2 (2.2) | .003 |

Two controls reported as alcohol-exposed during pregnancy.

Alcohol use during the index pregnancy was confirmed directly by the birth mother or through collateral sources in 100% of the ARND cases, 33% of the FAS cases, and 61% of the PFAS cases. When the diagnosis was made without direct reports from the mothers, confidential collateral reports from relatives and evidence from medical or social service records supported the dysmorphology evidence.

Prevalence of FASD Estimated by 3 Techniques

The final diagnoses of the individual children in the entire consented sample are presented in Table 5, section 1. Twelve children had FAS, 23 were diagnosed with PFAS, 13 had ARND, and none had alcohol-related birth defects. With the first prevalence estimation technique, 2 different denominators were used: the number of children enrolled in first grade classes at all schools (n = 2033), and the total number with consent to participate in this study (n = 1433). The assumption is that oversampling small children provided the highest probability of including most of the children who had FAS or PFAS. The rate of FAS with this technique is between 6 and 8 per 1000, the rate of combined FAS and PFAS is 17 to 24 per 1000, and total FASD is 24 to 34 per 1000 (see Table 5). For a single rate from this method, the midpoint is useful: FAS = 7.1, PFAS = 13.7, and total FASD = 28.6.

Alternatively, a second rate was calculated from the 16 cases of FASD found within the n = 196 who entered the study via random selection. The rates of FAS and total FASD from this technique are the highest of the 3 produced: 10 FAS cases per 1000 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0–24), the combined FAS and PFAS rate is 31 per 1000 (95% CI, 7–55), and the total FASD rate from this technique is 82 per 1000 (95% CI, 43–119).

The third rate was calculated from the number of total cases that would likely have been found in the 600 unconsented children. Projecting the proportions of FAS, PFAS, and ARND children found among the random sample (technique 2) to estimate the number of cases among the unconsented children and adding them to the cases diagnosed in the consented population, technique 3 estimates the rate of FAS to be 9, PFAS = 17, and a total FASD rate of 48 per 1000, or 4.8% (Table 5, section 3). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals make the range of FAS with this technique 39 to 57 per 1000. The final composite estimates of specific diagnoses of FASD and total FASD are found in Fig 5, section 3.

FIGURE 5.

Final estimate of prevalence of FASD in a Midwestern city.

Discussion

A variety of FASD cases, from FAS to ARND, was found in this general school population. And on most variables and physical and behavioral averages between FASD diagnostic categories and controls, the FASD traits form a linear continuum in which children who have FAS have the most deficits, followed by PFAS, ARND, and the normal controls. Both dysmorphology and maternal data link the teratogenic agent, alcohol, to the cases. We suspect substantial underreporting of alcohol during pregnancy; nevertheless, several reported drinking measures were significantly different between mothers of children who had FASD and controls 3 months before pregnancy, and the mothers of children who had a FASD recognized that they were pregnant later than others. Also, mothers of children who had a FASD indicated a non-statistically significant trend of more binge drinking, and their partners drank significantly more heavily than fathers of comparison children.

Making Sense of the Prevalence Findings

The prevalence of FAS cases in this study of first grade children in this general population is likely 6 to 9 per 1000 (see Fig 5). It is significantly higher than older, previously accepted estimates of FAS (0.2 to 3 per 1000) that were generated from less representative samples that did not use active case ascertainment.8,9,52 But these findings are similar to recent rates published for the United States, Italy, and Croatia, 2 to 7 per 1000,5,15–18 which used similar, active methods of case identification and as certainment. For FAS and PFAS combined, the likely maximum range of rates is 17 to 26 per 1000, and for total FASD, the rates range from 24 to 48 per 1000. Therefore, rates from this study are all well above the old estimate of 1% for total FASD.9 It is clear from this study that FAS, PFAS, and total FASD are far more common in this representative general population of first grade students than older estimates would predict.

The large ratio of PFAS and ARND cases to the FAS cases in the present sample is important for several reasons. First, the ability of our clinical team to diagnose less dysmorphic cases has improved with many years of experience, and the criteria for diagnosing the full spectrum are evolving.12 Second, the proportion of less dysmorphic to more dysmorphic cases seems indicative of a middle SES community with relatively favorable and stable environmental health conditions in which adequate dietary intake and fine universal educational institutions exist. Even with the oversampling of small children in this study, FAS cases identified here are only one-fourth of the children who had FASD, a pattern similar to findings in Italy. On the other hand, in recent studies of lower SES communities in South Africa, FAS cases are 45% or more of FASD cases.12 We believe this study is an accurate representation of a mainstream, middle SES population.

Physical Characteristics of the Children

By definition, all children diagnosed with FAS and PFAS met the facial criteria for at least 2 of the 3 cardinal features of FASD (palpebral fissure ≤10th percentile, smooth philtrum, and/or thin vermilion border of the upper lip), and had significantly smaller heads and BMIs than normal, randomly selected controls. The physical growth of children who had ARND was similar to the growth of other first graders. Not only the cardinal facial features, but other facial measurements and minor anomalies are also important discriminators of FASD. Based on this study and other population-based studies,10–13,15,16 other minor anomalies, such as those shown in Table 2, are reflected in the total dysmorphology score, which differentiates well the FASD diagnostic groups. Minor anomalies play an important role in identifying affected children.53

Cognitive and Behavioral Characteristics

In the cognitive/behavioral testing for this study and studies elsewhere,11,12 those who perform worse generally have more dysmorphology as well. Children who have a FASD performed poorly compared with controls on all cognitive tests and behavior rating instruments. Possibly because fewer of the children who had FAS remained in the study for testing (58% vs 70% with PFAS and 100% with ARND), the PFAS and ARND children performed most poorly compared with controls, especially on verbal IQ, working memory, general conceptual ability, and behavioral problems. Although total dysmorphology and poor cognitive/behavioral traits are correlated,11,12,34,54 there is also individual variation among the children on most every variable, each category of dysmorphology and performance.

Maternal Risk Measurements

In other study populations, maternal risk for FASD is more clearly defined by childbearing, SES variables, and binge-drinking measures than in this sample. Those populations that are characterized by lower SES generally have high fertility, poorer nutrition, more frequent and heavy binge drinking, and higher gravidity and parity, which more clearly differentiate mothers of children who had FASD from controls.10–12,55 In this middle SES Midwestern American sample, the only significant self-reported measures of maternal risk are longer duration before the mothers of children who had a FASD recognized pregnancy, fewer prenatal visits, more drinking reported 3 months before pregnancy, and heavy drinking by the father of children who had FASD. Drinking 3 months before pregnancy, a proxy for before-pregnancy recognition, has been a frequently recognized risk factor in many US and European studies.56–61 Recruitment of mothers to obtain maternal risk data posed significant challenges for the interviewers. Therefore, variables that differentiate maternal risk in this population were not as evident or readily obtained in this US population or in our Italian studies15,16 as elsewhere.23–25 Individualized risk for FASD via genetic and epigenetic factors may be more important to explore in this and similar middle and upper SES populations than the more generalized lower SES and childbearing risk factors of higher prevalence populations.12,16,52

Limitations

The consent rate for this study was high overall (70.5%). But there was some reluctance among particular individuals and families to continue throughout all parts of the study, as the consent process required signing several consent forms at various stages, which encouraged dropouts. Although 316 children were sought for psychological testing, only 65% of these children were tested, and 53% of the mothers sought were interviewed despite adequate incentives and up to 5 attempts to schedule an interview. Scheduling issues for 2-income families and a reluctance to continue in the study were problems in this population. Therefore, representativeness and completeness of the final sample is difficult to evaluate; to compensate, 3 sets of prevalence rates were calculated to produce a likely range of prevalence. A second limitation is the reluctance among mothers to report prenatal drinking. Only 33% of the mothers of children who had FAS and 61% of the mothers of children who had PFAS were interviewed. Studies elsewhere in the United States and Europe have reported similar problems62–64 and many have confirmed substantial underreporting by the use of biomarkers.65–68 Therefore, how underreporting affected the various maternal risk sample values is unknown. For example, the experienced interviewers estimated that at least 14% of the mothers of a child who had PFAS interviewed were clearly not fully forthcoming and truthful. Third, by initiating this study with assessment of child physical growth, development, and dysmorphology, the number of children with ARND and few dysmorphic features may have been under-identified, especially given the reluctance of mothers to report prenatal alcohol use. Therefore, the rate of ARND may be higher than reported here in the oversample estimate, but may be more accurately estimated from the 2 techniques based on random selection.

Conclusions

Children who have FASD, especially those who have FAS and PFAS, can be readily identified in mainstream school populations in the United States. The rate of FAS and overall FASD appear to be substantially higher in this community than most estimates for the general population of the United States, Canada, or Europe. In this community the rate of FASD is likely 6 to 9 per 1000 (midpoint, 7.5), 11 to 17 per 1000 (midpoint, 14) for PFAS, and 24 to 48 per 1000 (2.4% to 4.8%) for total FASD.

Acknowledgments

The project was started with supplemental stimulus funding to the first referenced grant and was later included in the NIAAA-funded initiative, Collaborative on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Prevalence (CoFASP) via the second referenced grant. Marcia Scott, PhD, Kenneth Warren, PhD, Faye Calhoun, DPA, and T-K Li, MD of NIAAA have provided intellectual guidance and support for prevalence studies of FASD for many years. Our deepest thanks are extended to the superintendent of schools, administrators, principals, psychologists, and teachers of the school system in the study community who have hosted and assisted in the research process over the years. Their professional support, guidance, and facilitation have been vital to the success of this study. We dedicate this paper to them and also to our deceased colleague, Dr Jason Blankenship, who invested much effort into this project before his untimely death.

Glossary

- ARND

alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI

95% confidence interval

- FASD

fetal alcohol spectrum disorders

- FAS

fetal alcohol syndrome

- IOM

Institute of Medicine

- OFC

occipitofrontal (head) circumference

- PFAS

partial fetal alcohol syndrome

- SES

socioeconomic status

Footnotes

Deceased.

Dr May is the Principal Investigator who designed the study, received the NIH funding, and wrote the majority of the first and last drafts of the manuscript; Ms Baete, Mr Russo, and Dr Elliott were respectively the program manager, project officer, and co-investigator who organized, implemented, and administered much of the data collection in the Midwestern city, and each contributed written text and edited various drafts of the manuscript; Dr Blankenship performed much of the data and statistical analyses, contributed written text and interpretation, constructed some tables, and edited various drafts of the manuscript before his sudden death on October 29, 2013; Ms Kalberg, Mr Buckley, and Ms Brooks were the designers and supervisors of the field data collection, data management, data entry, and Institutional Review Board activities, and each read drafts and edited the manuscript; Ms Hasken contributed to and edited each draft of the manuscript and produced original figures and the final tables and figures; Drs Abdul-Rahman, Adam, Robinson, and Manning were project dysmorphologists who diagnosed and generated clinical dysmorphology data in field clinics and made final diagnoses; Dr Hoyme was co-Principal Investigator for the site and the chief dysmorphologist supervising the clinical team members, administering clinical examinations, and generating data, he was chief medical officer assuming responsibility for medical liaison with the schools, families, and local administration, and he contributed written material and edited various drafts of the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse, and Alcoholism (NIAAA), grants R01 AA11685, and RO1/UO1 AA01115134. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Jones KL, Smith DW. Recognition of the fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy. Lancet. 1973;302(7836):999–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson GC, Conry JL, Conry RF. Clinical profile and prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome in an isolated community in British Columbia. CMAJ. 1987;137(3):203–207 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.May PA, Hymbaugh KJ, Aase JM, Samet JM. Epidemiology of fetal alcohol syndrome among American Indians of the Southwest. Soc Biol. 1983;30(4):374–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.May PA, Gossage JP. Estimating the prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome. A summary. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25(3):159–167 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.May PA, Gossage JP, Kalberg WO, et al. Prevalence and epidemiologic characteristics of FASD from various research methods with an emphasis on recent in-school studies. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15(3):176–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Surveillance for fetal alcohol syndrome using multiple sources — Atlanta, Georgia, 1981-1989. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46(47):1118–1120 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Update: trends in fetal alcohol syndrome—United States, 1979-1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(13):249–251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratton KR, Howe CJ, Battaglia FC, eds. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Prevention, and Treatment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sampson PD, Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, et al. Incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome and prevalence of alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder. Teratology. 1997;56(5):317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.May PA, Brooke L, Gossage JP, et al. Epidemiology of fetal alcohol syndrome in a South African community in the Western Cape Province. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1905–1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.May PA, Gossage JP, Marais AS, et al. The epidemiology of fetal alcohol syndrome and partial FAS in a South African community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(2-3):259–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.May PA, Blankenship J, Marais AS, et al. Approaching the prevalence of the full spectrum of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in a South African population-based study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(5):818–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viljoen DL, Gossage JP, Brooke L, et al. Fetal alcohol syndrome epidemiology in a South African community: a second study of a very high prevalence area. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(5):593–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urban M, Chersich MF, Fourie LA, Chetty C, Olivier L, Viljoen D. Fetal alcohol syndrome among grade 1 schoolchildren in Northern Cape Province: prevalence and risk factors. S Afr Med J. 2008;98(11):877–882 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May PA, Fiorentino D, Phillip Gossage J, et al. Epidemiology of FASD in a province in Italy: Prevalence and characteristics of children in a random sample of schools. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(9):1562–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.May PA, Fiorentino D, Coraile G, et al. Prevalence of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in communities near Rome, Italy: rates are substantially higher than previous estimates. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(6):2331–2351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petković G, Barisić I. FAS prevalence in a sample of urban schoolchildren in Croatia. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;29(2):237–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petković G, Barišić I. Prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome and maternal characteristics in a sample of schoolchildren from a rural province of Croatia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(4):1547–1561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adnams CM, Kodituwakku PW, Hay A, Molteno CD, Viljoen D, May PA. Patterns of cognitive-motor development in children with fetal alcohol syndrome from a community in South Africa. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(4):557–562 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kodituwakku P, Coriale G, Fiorentino D, et al. Neurobehavioral characteristics of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in communities from Italy: Preliminary results. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(9):1551–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aragón AS, Coriale G, Fiorentino D, et al. Neuropsychological characteristics of Italian children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(11):1909–1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalberg WO, May PA, Blankenship J, Buckley D, Gossage JP, Adnams CM. A practical testing battery to measure neurobehavioral ability among children with FASD. Int J Alcohol Drug Res. 2013;2(3):51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viljoen D, Croxford J, Gossage JP, Kodituwakku PW, May PA. Characteristics of mothers of children with fetal alcohol syndrome in the Western Cape Province of South Africa: a case control study. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(1):6–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.May PA, Gossage JP, Brooke LE, et al. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol syndrome in the Western cape province of South Africa: a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1190–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.May PA, Gossage JP, Marais AS, et al. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol syndrome and partial fetal alcohol syndrome in South Africa: a third study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(5):738–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Census Bureau. State & County Quick Facts. Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/index.html#. Accessed April 1, 2014

- 27.LaVallee RA, Yi H. Surveillance Report #92: Apparent Per Capita Alcohol Consumption: National, State, And Regional Trends, 1977–2009. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Department of Health and Human Service. County Alcohol Problem Indicators 1989–1990. Rockville, MD; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 29.United Health Foundation. America’s Health Rankings. Available at: www.americashealthrankings.org. Accessed April 1, 2014

- 30.US counties. Available at: www.city-data.com/countyDir.html. Accessed April 1, 2014

- 31.Office of Health Statistics The Health Behaviors of South Dakotans 2011. Pierre, SD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoyme HE, May PA, Kalberg WO, et al. A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: clarification of the 1996 institute of medicine criteria. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):39–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alvik A, Haldorsen T, Lindemann R. Alcohol consumption, smoking and breastfeeding in the first six months after delivery. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(6):686–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.May PA, Tabachnick BG, Gossage JP, et al. Maternal risk factors predicting child physical characteristics and dysmorphology in fetal alcohol syndrome and partial fetal alcohol syndrome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119(1-2):18–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wurst FM, Kelso E, Weinmann W, Pragst F, Yegles M, Sundström Poromaa, I. Measurement of direct ethanol metabolites suggests higher rate of alcohol use among pregnant women than found with the AUDIT—a pilot study in a population-based sample of Swedish women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):407.e1–e5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Ervalahti N, Korkman M, Fagerlund A, Autti-Rämö I, Loimu L, Hoyme HE. Relationship between dysmorphic features and general cognitive function in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(24):2916–2923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beery K, Buktenica N, Beery N. Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration, 5th ed. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Assessments; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elliott CD. Differential Ability Scales, 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment, Inc, Pearson Education, Inc; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Balla DA. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Assessments; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sobell LC, Agrawal S, Annis H, et al. Cross-cultural evaluation of two drinking assessment instruments: alcohol timeline followback and inventory of drinking situations. Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36(3):313–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br J Addict. 1988;83(4):393–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaskutas LA, Graves K. An alternative to standard drinks as a measure of alcohol consumption. J Subst Abuse. 2000;12(1-2):67–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaskutas LA, Graves K. Pre-pregnancy drinking: how drink size affects risk assessment. Addiction. 2001;96(8):1199–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaskutas LA, Kerr WC. Accuracy of photographs to capture respondent-defined drink size. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(4):605–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.King AC. Enhancing the self-report of alcohol consumption in the community: two questionnaire formats. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(2):294–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alvik A, Haldorsen T, Groholt B, Lindemann R. Alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy comparing concurrent and retrospective reports. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(3):510–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Czarnecki DM, Russell M, Cooper ML, Salter D. Five-year reliability of self-reported alcohol consumption. J Stud Alcohol. 1990;51(1):68–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hannigan JH, Chiodo LM, Sokol RJ, et al. A 14-year retrospective maternal report of alcohol consumption in pregnancy predicts pregnancy and teen outcomes. Alcohol. 2010;44(7-8):583–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Microsoft Excel [computer software]. Version 2007. Redmond, WA: Microsoft; 2007

- 50.IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows [computer program]. Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2011

- 51.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 52.May PA, Gossage JP. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: not as simple as it might seem. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34(1):15–26 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feldman HS, Jones KL, Lindsay S, et al. Prenatal alcohol exposure patterns and alcohol-related birth defects and growth deficiencies: a prospective study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(4):670–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.May PA, Tabachnick BG, Gossage JP, et al. Maternal factors predicting cognitive and behavioral characteristics of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013;34(5):314–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abel EL. Fetal Alcohol Abuse Syndrome. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Balachova T, Bonner B, Chaffin M, et al. Women’s alcohol consumption and risk for alcohol-exposed pregnancies in Russia. Addiction. 2012;107(1):109–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Floyd RL, Decouflé P, Hungerford DW. Alcohol use prior to pregnancy recognition. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17(2):101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mallard SR, Connor JL, Houghton LA. Maternal factors associated with heavy periconceptional alcohol intake and drinking following pregnancy recognition: a post-partum survey of New Zealand women. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32(4):389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parackal SM, Parackal MK, Harraway JA. Prevalence and correlates of drinking in early pregnancy among women who stopped drinking on pregnancy recognition. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(3):520–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Russell M, Czarnecki DM, Cowan R, McPherson E, Mudar PJ. Measures of maternal alcohol use as predictors of development in early childhood. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15(6):991–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Skagerström J, Alehagen S, Häggström-Nordin E, Årestedt K, Nilsen P. Prevalence of alcohol use before and during pregnancy and predictors of drinking during pregnancy: a cross sectional study in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alvik A, Haldorsen T, Lindemann R. Consistency of reported alcohol use by pregnant women: anonymous versus confidential questionnaires with item nonresponse differences. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(8):1444–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alvik A, Heyerdahl S, Haldorsen T, Lindemann R. Alcohol use before and during pregnancy: a population-based study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(11):1292–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ortega-García JA, Gutierrez-Churango JE, Sánchez-Sauco MF, et al. Head circumference at birth and exposure to tobacco, alcohol and illegal drugs during early pregnancy. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28(3):433–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bryanton J, Gareri J, Boswall D, et al. Incidence of prenatal alcohol exposure in Prince Edward Island: a population-based descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(2):E121–E126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manich A, Velasco M, Joya X, et al. [Validity of a maternal alcohol consumption questionnaire in detecting prenatal exposure]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2012;76(6):324–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morini L, Marchei E, Tarani L, et al. Testing ethylglucuronide in maternal hair and nails for the assessment of fetal exposure to alcohol: comparison with meconium testing. Ther Drug Monit. 2013;35(3):402–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pichini S, Marchei E, Vagnarelli F, et al. Assessment of prenatal exposure to ethanol by meconium analysis: results of an Italian multicenter study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(3):417–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]