Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Perinatal complications predict increased risk for morbidity and early mortality. Evidence of perinatal programming of adult mortality raises the question of what mechanisms embed this long-term effect. We tested a hypothesis related to the theory of developmental origins of health and disease: that perinatal complications assessed at birth predict indicators of accelerated aging by midlife.

METHODS:

Perinatal complications, including both maternal and neonatal complications, were assessed in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study cohort (N = 1037), a 38-year, prospective longitudinal study of a representative birth cohort. Two aging indicators were assessed at age 38 years, objectively by leukocyte telomere length (TL) and subjectively by perceived facial age.

RESULTS:

Perinatal complications predicted both leukocyte TL (β = −0.101; 95% confidence interval, −0.169 to −0.033; P = .004) and perceived age (β = 0.097; 95% confidence interval, 0.029 to 0.165; P = .005) by midlife. We repeated analyses with controls for measures of family history and social risk that could predispose to perinatal complications and accelerated aging, and for measures of poor health taken in between birth and the age-38 follow-up. These covariates attenuated, but did not fully explain the associations observed between perinatal complications and aging indicators.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our findings provide support for early-life developmental programming by linking newborns’ perinatal complications to accelerated aging at midlife. We observed indications of accelerated aging “inside,” as measured by leukocyte TL, an indicator of cellular aging, and “outside,” as measured by perceived age, an indicator of declining tissue integrity. A better understanding of mechanisms underlying perinatal programming of adult aging is needed.

Keywords: perinatal complications, developmental programming, aging, telomere length, perceived age

What’s Known on This Subject:

Perinatal complications predict increased risk for morbidity and early mortality. Evidence of perinatal programming of adult mortality raises the question of what mechanisms embed this long-term effect. Telomere length and perceived facial age are 2 indicators of accelerated aging.

What This Study Adds:

Perinatal complications predicted greater signs of accelerated aging “inside,” as measured objectively by leukocyte telomere length, an indicator of cellular aging, and “outside,” as measured subjectively by perceived age, an indicator of declining integrity of tissues.

The model of the developmental origins of health and disease suggests that impaired growth in utero may permanently change the body’s function and metabolism, resulting in accelerated aging.1 Adverse conditions during early development exert a major impact on the etiology and programming of late-life chronic diseases and early mortality.2–6 Evidence of perinatal programming of adult mortality raises the question of what mechanisms embed this long-term effect. We tested the hypothesis that perinatal complications are associated with biomarkers of accelerated aging already at midlife, before onset of aging-related diseases.

Two biomarkers associated with accelerated aging are telomere length (TL) and perceived age.7,8 Telomeres, the protective caps at the end of chromosomes, erode in somatic tissues with each division of a cell. Both animal and human studies support a link between short TL and early mortality.9–13 Thus, the length of telomeres has been proposed as a “biological clock” for studying cellular aging across the life span and can be observed already in midlife while people are still healthy.14,15 New work has raised the possibility of fetal programming of telomere biology, whereby stress-related maternal–placental–fetal interactions during intrauterine growth regulate the initial setting of TL at birth.6,16,17 Perceived facial age is an assessment of how old a person looks relative to his or her chronological age. The visual signs of aging (eg, skin wrinkles) reflect declining tissue integrity, indicative of the aging process.18 Perceived age is widely used as a general indicator of health by clinicians and is correlated with both TL and early mortality.8,18,19

We tested the hypothesis that people who experienced perinatal complications would exhibit these signs of accelerated aging by midlife. We followed a cohort prospectively from birth to age 38 years and tested whether those with perinatal complications (assessed at birth) exhibited greater signs of aging inside and outside, that is, at the cellular level (TL) and at the level of facial appearance (perceived age).

Methods

Participants

Participants are members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a longitudinal investigation of health and behavior in a complete birth cohort. Study members (N = 1037; 91.0% of eligible births; 52.0% male) were all born between April 1972 and March 1973 in Dunedin, New Zealand, were eligible for the longitudinal study based on residence in the Otago province at age 3, and participated in the first follow-up assessment at age 3. The cohort represents the full range of socioeconomic status (SES) in the general population of New Zealand’s South Island and is primarily white. Assessments were carried out at birth and at ages 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, 32, and, most recently, 38 years, when 95.4% of the 1007 living study members underwent assessment in 2010 to 2012. At each assessment wave, each study member is brought to the Dunedin Research Unit for a full day of interviews and examinations. All analyses reported in this study were restricted to white study members who consented to phlebotomy and facial photographs at the age-38 assessment and had data on all measures used here (N = 829). DNA for study members of Maori ancestry is not transported to Duke University for analysis for cultural reasons. There have been 30 deaths since age 3; however, these deaths were not due to aging-related diseases. Causes include road accidents, suicide, overdose, and childhood cancers. By age 38 years, 8 of 829 study members had developed an aging-related diagnosis of type II diabetes, heart attack, stroke, or cancer. The Otago Ethics Committee approved each phase of the study, and informed consent was obtained from all study members.

Assessment of Perinatal Complications

Each child was examined shortly after birth, and perinatal information was taken from the hospital records.20,21 As previously described,20 the obstetric complications assessed in this study, including prenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal complications, were maternal diabetes, glycosuria, epilepsy, hypertension, eclampsia, antepartum hemorrhage, accidental hemorrhage, placenta previa, having had a previous small baby, gestational age <37 weeks or >41 weeks, birth weight <2.5 kg, small size for gestational age, major or minor neurologic signs of the neonatal period (eg, jitteriness, tenseness, limpness, hypotonicity), Rh incompatibility, ABO incompatibility, nonhemolytic hyperbilirubinemia, hypoxia at birth (idiopathic respiratory distress syndrome or apnea), and low Apgar score at birth. The infant was defined as having a low Apgar score if 1 of the following conditions applied: At 5 minutes of life, the infant’s heart rate was 100 beats per minute, respiration was irregular or absent, and the infant was centrally cyanotic; the infant took >10 minutes to establish normal respiration; or the infant’s asphyxia at birth warranted resuscitation. The sum of maternal complications and neonate complications was significantly and positively correlated (r = 0.156, P < .001). Based on evidence that the effects of adverse conditions are cumulative,22,23 each condition was weighted equally and summed to yield an obstetric complications index. A total of 530 study members (63.9%) had 0 perinatal complications, 211 (25.5%) had 1 perinatal complication, and 88 (11%) had ≥2.

Assessment of Aging Indicators

Measurement of Mean Relative TL at Age 38 Years

We extracted leukocyte DNA from blood using standard procedures.24,25 Age-38 DNA was stored at −80°C until assayed, to prevent degradation of the samples. All DNA samples were assayed for leukocyte TL at the same time, independently of caseness, and all operations were carried out by a laboratory technician blind to cases or controls. We measured TL by using a validated quantitative polymerase chain reaction method,26 as previously described,27,28 which determines mean TL across all chromosomes for all cells sampled. The method involves 2 quantitative polymerase chain reactions for each subject: 1 for a single-copy gene (S) and the other in the telomeric repeat region (T). All DNA samples were run in triplicate for telomere and single-copy reactions at age 38 years (ie, 6 reactions per study member). The average coefficient of variation for the triplicate cycle threshold values was 0.82% for the T and 0.48% for the S, indicating high assay precision. TL, as measured by T/S ratio, was normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests of normality), with a skew of 0.48 and kurtosis of 0.38 at age 38.

Perceived Age at 38 Years

We took 2 measurements of perceived age. First, “age range” was assessed by an independent panel of 4 Duke University undergraduate raters. In a previous methodology article it was shown that raters’ gender, nationality, age, and aging expertise had little effect on the perceived age data generated.18 Raters were presented with standardized (nonsmiling) facial photographs of study members and were kept blind to their actual age. Photos were divided into gender-segregated slideshow batches containing ∼50 photos, viewed for 10 seconds each. Raters were randomly assigned to viewing the slideshow batches in either forward progression or backward progression. They used a Likert scale to categorize each study member into a 5-year age range (ie, from 1 = 20–24 years old up to 10 = 65–70 years; mean = 4.21, SD = 0.76). Scores for each study member were averaged across all raters (α = 0.71). The second measure, “relative age”, was assessed by a different panel of 4 Duke University undergraduate raters. The raters were told that all photos were of people aged 38 years old. Raters then used a 7-item Likert scale to assign a relative age to each study member (1 = young looking, 7 = old looking; mean = 4.14, SD = 0.91). Scores for each study member were averaged across all raters (α = 0.72). “Age range” and “relative age” were highly correlated (r = 0.73). To derive a measure of perceived age at 38 years, we standardized and averaged both “age range” and “relative age” scores to create perceived age at 38 years.

Alternative Explanatory Variables

We tested for measures of family history and social risk that could predispose to both perinatal complications and accelerated aging, potentially creating an artifactual association between them. Furthermore, we tested for measures of poor health taken between birth and age-38 follow-up that are known outcomes of perinatal complications,4,5,29–31 and could mediate an association between perinatal complications and accelerated aging. These alternative explanatory variables have been previously published and have good reliability and validity in this cohort. They included family histories of medical problems, childhood social adversity, and poor cognitive health, mental health, vascular health, or physical health. All alternative explanatory variables are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Description of Alternative Explanatory Variables That May Explain the Association Between Perinatal Complications and Aging Indicators at 38 y

| Alternative Explanatory Variable | Description | Assessment Ages | Perinatal Complications (Mean, SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family histories of medical problems | In 2003–2006, we interviewed study members and their biological parents to obtain histories of medical problems about study members’ first- and second-degree relatives.54 The following conditions were assessed: heart disease (defined as a history of heart attack, balloon angioplasty, coronary bypass, or angina), stroke, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, asthma, and cancer. We created the family history score indicating medical problems by calculating the proportion of a study member’s extended family with a positive history of any medical problem. | Lifetime | 0 (3.87, 1.13) |

| 1 (3.72, 1.07) | |||

| ≥2 (3.66, 1.13) | |||

| Childhood social adversity | The SES of study members’ families was measured with a 6-point scale assessing parents’ occupational status. The scale places each occupation into 1 of 6 categories (from 1, unskilled laborer to 6, professional) on the basis of education levels and income associated with that occupation in data from the New Zealand census. Family SES was the average of the highest SES level of either parent from birth through age 15 y. This variable reflects the socioeconomic conditions experienced by the participants while they were growing up. | Birth to 11 y | 0 (1.08, 0.50) |

| 1 (1.12, 0.48) | |||

| ≥2 (1.15, 0.51) | |||

| Cognitive health | Intelligence tests were administered in childhood at ages 7, 9, 11, and 13 y and again in adulthood at age 38 y. We used the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Revised55 and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Fourth Edition.56 These tests comprise a series of subtests that yield indices standardized to population norms (M = 100, SD = 15). To derive a measure of life course cognitive health, we created an average IQ score by using data from 7 to 38 y. | 7–38 y | 0 (101.41, 13.73) |

| 1 (99.49, 13.81) | |||

| ≥2 (96.57, 14.28) | |||

| Mental health | Psychiatric disorders (according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association) were assessed among study members via private structured interviews using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule at ages 18, 21, 26, 32, and 38 y. We repeatedly assessed the following disorders by using 1-year reporting periods: alcohol dependence, cannabis dependence, dependence on hard drugs, tobacco dependence (assessed with the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence),57 conduct disorder, major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, fears and phobias, obsessive–compulsive disorder, mania, and schizophrenia. As previously described,58 we carried out confirmatory factor analyses of these psychiatric disorders, taking into account their persistence, co-occurrence, and sequential comorbidity, from ages 18–38 y. The structure of mental disorders could be summarized by 3 core psychopathological dimensions: an internalizing liability to depression and anxiety, an externalizing liability to antisocial and substance use disorders, and a thought disorder liability to symptoms of psychosis. At a higher-order level, we showed that these liabilities themselves reflected 1 general underlying dimension that summarized subjects’ propensity to develop any form of common psychiatric and substance use disorders.58 Higher scores on this dimension index persistent and impairing mental illness. | 18–38 y | 0 (98.24, 13.93) |

| 1 (101.14, 15.51) | |||

| ≥2 (99.14, 15.24) | |||

| Vascular health | Blood pressure at ages 26, 32, and 38 y was assessed according to standard protocols59 using a Hawksley random-zero sphygmomanometer (Hawksley & Sons Ltd, Lancing, UK) with a constant deflation valve. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were combined to derive a measure of mean arterial pressure: [(2 × diastolic) + systolic]/3. To derive a measure of vascular health, we averaged all 3 mean arterial pressure variables at 26, 32, and 38 y. | 26–38 y | 0 (89.41, 7.69) |

| 1 (90.25, 7.63) | |||

| ≥2 (89.76, 7.25) | |||

| Physical health | Physical health at ages 26, 32, and 38 y was measured by clinical indicators of poor adult health, including metabolic abnormalities (waist circumference, high-density lipoprotein level, triglyceride level, blood pressure, and glycated hemoglobin), poor cardiorespiratory fitness, poor pulmonary function, periodontal disease, and systemic inflammation (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) (Supplemental Table 3). Pregnant women were excluded from the reported analyses. We summed the number of clinical indicators on which study members exceeded clinical cutoffs at each age. To derive a measure of physical health, we averaged all 3 physical health indexes at 26, 32, and 38 y. (Blood pressure duplicates vascular health, but we retained it in the physical health index because it is a standard constituent of a clinical physical health examination). | 26–38 y | 0 (1.37, 1.05) |

| 1 (1.56, 1.12) | |||

| ≥2 (1.34, 1.00) |

Statistics

We tested the hypothesis that perinatal complications predict aging indicators at age 38 years by regressing each of age-38 TL and age-38 perceived age on a predictor variable indicating the number of perinatal complications for which study members met criteria. To test the possibility that the association between perinatal complications and aging indicators was a consequence of alternative explanatory variables, we reanalyzed the association between perinatal complications and aging indicators, controlling for these variables in ordinary least squares multiple regression analyses. We report standardized coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the 2 aging outcomes. Age was not controlled statistically, because all study members were the same age (1972–1973 births).

Results

Both our subjective and objective aging indicators were related in the expected direction. Age-38 leukocyte TL and perceived age were significantly and negatively correlated (r = −0.086, P = .01). Study members with shorter telomeres tended to look older.

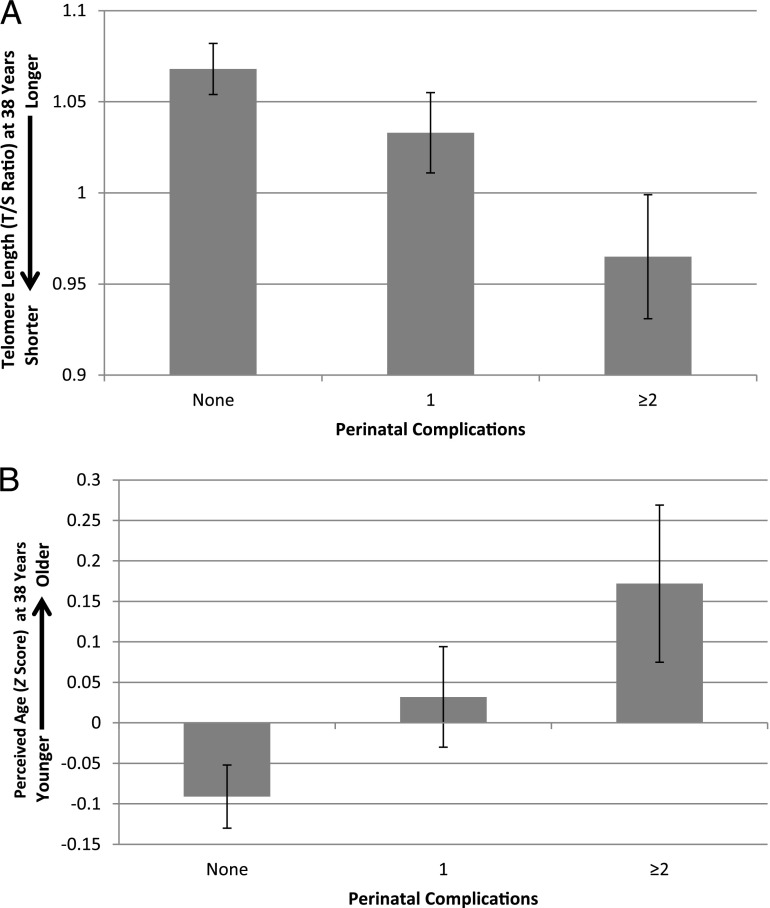

Perinatal complications predicted both age-38 TL (β = −0.101; 95% CI, −0.169 to −0.033; P = .004) (Fig 1A) and age-38 perceived age (β = 0.097; 95% CI, 0.029–0.165; P = .005) (Fig 1B). Study members who had more perinatal complications had shorter telomeres and looked older. Although women had somewhat longer age-38 telomeres than men (men = 1.038 T/S ratio; women = 1.059 T/S ratio, P = .351), associations between perinatal complications and aging indicators did not differ significantly between men and women, which is consistent with results of a recent meta-analysis.32 There was no significant interaction between gender and perinatal complications predicting either TL (β = −0.044; 95% CI, −0.112 to 0.025; P = .21; the T/S ratios for men with 0, 1, and ≥2 perinatal complications were 1.075, 0.961, and 0.983; the comparable T/S ratios for women were 1.061, 1.103, and 0.955) or perceived age (β = 0.010; 95% CI, −0.059 to 0.078; P = .78; the standardized perceived age of men with 0, 1, and ≥2 perinatal complications was −0.051, 0.118, and 0.209; the comparable scores for women were −0.132, −0.055, and 0.131).

FIGURE 1.

Association between perinatal complications and (A) leukocyte TL (T/S ratio) and (B) perceived facial age (Z score) at midlife. Error bars reflect SEs.

We next tested whether alternative explanatory variables that may be associated with perinatal complications, TL, and perceived age accounted for the association between perinatal complications and aging indicators. Table 2 shows that shorter age-38 TL was significantly correlated with family histories of medical problems and poor cognitive health, mental health, and vascular health (P < .05), but not with childhood social adversity (low SES), which is consistent with previous research.33 Age-38 perceived age was significantly correlated with childhood social adversity and poor cognitive health, mental health, and physical health (P < .05). Controlling for these alternative explanatory variables attenuated, but did not fully explain the associations observed between perinatal complications and aging indicators (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Pearson Correlations and Multivariate Linear Regression Analyses of Perinatal Complications, Predicting Leukocyte TL and Perceived Age at 38 y, Controlling for Alternative Explanatory Variables and Gender (N = 829)

| Bivariate Pearson Correlation | Association Between Perinatal Complications and TL at 38 y | Association Between Perinatal Complications and Perceived Age at Age 38 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perinatal Complications | TL at 38 y | Perceived Age at 38 y | β (95% CI) | P | β (95% CI) | P | |

| Perinatal complications | — | — | — | −0.101 (−0.169 to −0.033) | .004 | 0.097 (0.029 to 0.165) | .005 |

| Controlling for alternative explanatory variables (and gender) | |||||||

| Family histories of medical problems | 0.051 | −0.090** | 0.007 | −0.097 (−0.164 to −0.029) | .005 | 0.096 (0.028 to 0.164) | .006 |

| Childhood social adversitya | −0.070* | 0.041 | −0.194** | −0.098 (−0.167 to −0.030) | .005 | 0.083 (0.016 to 0.150) | .01 |

| Life course health | |||||||

| Cognitive healtha | −0.111** | 0.087* | −0.186** | −0.092 (−0.161 to −0.024) | .008 | 0.077 (0.010 to 0.144) | .02 |

| Mental health | 0.055 | −0.070* | 0.162** | −0.097 (−0.165 to −0.029) | .005 | 0.088 (0.021 to 0.155) | .01 |

| Vascular health | 0.033 | −0.069* | −0.022 | −0.098 (−0.166 to −0.029) | .005 | 0.100 (0.031 to 0.168) | .004 |

| Physical health | 0.031 | −0.057 | 0.193** | −0.099 (−0.167 to −0.031) | .004 | 0.089 (0.022 to 0.156) | .009 |

| All variables | — | — | — | −0.084 (−0.152 to −0.016) | .02 | 0.075 (0.009 to 0.140) | .02 |

Higher scores indicate lower childhood social adversity or better cognitive health.

P < .05;

P < .01.

Finally, we tested whether specific perinatal complications were associated with accelerated aging indicators. Although our sample size was not large enough to interrogate each specific type of complication, we had enough cases to interrogate the 2 most common complications: low birth weight (<2.5 kg; N = 43) and small size for gestational age (N = 72).1,34,35 These 2 complications are not synonymous; they were correlated at r = 0.33, and only 29% of infants small for gestational age were low birth weight, as in the general population. Low birth weight predicted both age-38 TL (β = −0.074; 95% CI, −0.142 to −0.006; P = .03) and age-38 perceived age (β = 0.092; 95% CI, 0.024 to 0.160; P = .008). Likewise, small size for gestational age predicted both aging indicators at 38 years (TL, β = −0.074; 95% CI, −0.142 to −0.006; P = .03; perceived age, β = 0.087; 95% CI, 0.019 to 0.155; P = .01).

Discussion

Following a cohort from birth to midlife, we found that newborns who presented with more perinatal complications exhibited greater signs of accelerated aging at age 38 years. We observed indications of accelerated aging inside, as measured objectively by leukocyte TL, an indicator of cellular aging, and outside, as measured subjectively by perceived age, an indicator of declining tissue integrity.

This prospective longitudinal investigation has several strengths. First, all cohort members were the same age, strengthening the test of variation in their pace of aging. Second, the cohort was young enough to detect variation in aging indicators before diseases of aging have begun to develop. Third, we tested 2 indicators of accelerated aging. Although some commentators have questioned whether TL is an appropriate biomarker of aging,36 we confirmed a previous report that shorter TL is associated with older perceived age in the expected direction.8

We used a perinatal complication index that was previously shown to predict cognitive problems in the Dunedin Study at ages 3, 5, 7, 11, and 13 years.20,37 Notably, our index also predicted a measure of cognitive health averaged from 7 to 38 years (Table 2). There are several approaches for scoring perinatal complications. The 3 most common are a present or absent count of complications38,39 (as is our index), a weighted severity scale based on a clinician’s judgment of risk,40 and a method that uses empirical probabilities of morbidity associated with each perinatal condition.41 A recent review of these approaches for constructing perinatal risk scales concluded that all of them predict cognitive outcomes similarly.23 This review also noted that the ideal system should include prenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal complications; contain items that are commonly measured to assess perinatal risk; have a few items rather than potentially hundreds; and be able to predict developmental outcomes in infancy and early childhood. The Dunedin Study index fulfills these requirements. Although some individual complications can have strong predictive utility,23 our sample size was not large enough to interrogate each specific complication individually (eg, Apgar score or hypoxia). However, the 2 most common complications, low birth weight and small size for gestational age, were significantly associated with both aging indicators at similar effect sizes.

We acknowledge limitations. First, the Dunedin cohort is primarily white and represents a single birth cohort born in the 1970s. Replication of associations between perinatal complications and aging indicators in other ethnic groups and cohorts is needed. Second, we did not measure TL at birth, given that this technology was not available in the early 1970s, and perceived facial age is not an appropriate measure in this stage of development. This means that we could study only individual differences in indicators of accelerated aging rather than changes from a neonate baseline. Furthermore, we did not control for paternal age at conception, nor did we measure TL in parents, and therefore we could not interrogate whether shorter TL in parents increased neonates’ probability to develop complications at birth. Facial age ratings might be affected by factors apart from aging (eg, sun exposure, fair complexion), so this measure is somewhat noisy, yet there is no obvious reason to suggest such factors covary with perinatal complications to confound our analyses. Perinatal complications predicted TL and facial aging at small effect sizes, but they were comparable to the effect size between perinatal complications and cognitive health (IQ).

Surprisingly, the association between perinatal complications and aging indicators was not explained by potentially confounding measures of family history and social risk that could predispose to both perinatal complications and accelerated aging, nor was it explained by potentially mediating measures of health taken between birth and age-38 follow-up. This finding, though unexpected, is consistent with previous reports that perinatal complications predict accelerated aging independently of risk factors such as childhood SES, adulthood SES, smoking, and hypertension.42,43 If the association between perinatal complications and the rate of aging at midlife is truly independent of family history and social risks present before birth, and of health states during the first half of the life course, it would suggest that perinatal complications are a primary exposure rather than an indicator of some preexisting risk and that the aging indicators we studied capture information not observable in outward manifestations of health during the first half of the life course.

Efforts to elaborate the model of the developmental origins of health and disease are concerned with potential mechanisms of perinatal programming. Our correlational observations suggest the hypothesis of a cellular mechanism linking perinatal complications with accelerated aging through erosion of TL.44 Additional support for the accelerated aging process is given by the observation that subjects with perinatal complications tended to look older by midlife. If replicated, the link between perinatal complications and shorter TL suggests several hypotheses for experimental investigations. Future research should elucidate the molecular pathways by which the connection between perinatal complications and accelerated aging occurs.4,14,45 Additional research on younger people needs to test when in life the effect of perinatal complications on TL can initially be observed. Moreover, clinical trials in NICUs could incorporate TL or telomerase measurements at birth, and thereafter at follow-up, as a first step to test the potential early reversibility of this developmental programming of disease. Finally, there is interest in factors that protect some people from the aging-accelerating consequences of perinatal complications. A challenge in pursuing research on this topic is that it is difficult to determine who is resilient until late in life, when diseases of old age have had time to develop. Facial aging and TL provide an opportunity to identify adults at midlife who appear to be resilient to perinatal complications.

Conclusions

Perinatal complications predicted greater signs of accelerated aging by midlife. Since our cohort was born in the 1970s, advances in obstetric medicine, particularly in developed countries, have reduced infant mortality and saved lives.46,47 Advances in obstetric medicine in developing regions, home to >80% of the world’s population, will soon also increase the number of survivors with perinatal complications.48–50 Birth outcomes are important determinants of a range of adult attainments,47 and previous research indicates that many newborns who survive perinatal complications carry a lifelong vulnerability to poor health.2–5 Here we present evidence of such sustained vulnerability emerging already in midlife, before aging-related diseases begin to develop. Understanding the underlying mechanism is critical to devising effective intervention strategies. Our findings encourage additional investigation of the link between perinatal complications and indicators of aging in early life.51–53

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Dunedin study members, unit research staff, Bob Hancox, Murray Thomson, and study founder Phil Silva. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethical review boards of the participating universities. Study members gave informed consent before participating.

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- S

single-copy gene

- SES

socioeconomic status

- T

telomere

- TL

telomere length

Footnotes

Dr Shalev was involved in conception of the study and in reviewing the literature, analyzing and interpreting the data, and writing the draft manuscript; Drs Caspi and Moffitt were involved in the conception and design of the study and in analyzing and interpreting the data and writing the draft manuscript; Mr Ambler, Drs Chapple, Poulton, and Ramrakha, Ms Rivera, Dr Sugden, and Mr Williams were involved in the conception, design, and management of the study; Dr Belsky was involved in the conception of the study and in analyzing and interpreting the data; Drs Cohen, Israel, and Wolke reviewed the report; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: This research received support from the US National Institute of Aging (grant AG032282) and the UK Medical Research Council (grant MR/K00381X). The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit is supported by the New Zealand Health Research Council. Additional support was provided by the Jacobs Foundation. Dr Belsky was supported by National Institute on Aging grants T32-AG00029 and P30-AG028716-08. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found on page e1411, online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2014-2646.

References

- 1.Barker DJP. The origins of the developmental origins theory. J Intern Med. 2007;261(5):412–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crump C, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Gestational age at birth and mortality in young adulthood. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1233–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swamy GK, Ostbye T, Skjaerven R. Association of preterm birth with long-term survival, reproduction, and next-generation preterm birth. JAMA. 2008;299(12):1429–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(1):61–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Onofrio BM, Class QA, Rickert ME, Larsson H, Långström N, Lichtenstein P. Preterm birth and mortality and morbidity: a population-based quasi-experimental study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(11):1231–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wadhwa PD. Psychoneuroendocrine processes in human pregnancy influence fetal development and health. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(8):724–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epel ES. Telomeres in a life-span perspective: a new “psychobiomarker”? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(1):6–10 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen K, Thinggaard M, McGue M, et al. Perceived age as clinically useful biomarker of ageing: cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b5262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heidinger BJ, Blount JD, Boner W, Griffiths K, Metcalfe NB, Monaghan P. Telomere length in early life predicts lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(5):1743–1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaefer C, Sciortino S, Kvale M, et al. B4-3: demographic and behavioral influences on telomere length and relationship with all-cause mortality: early results from the Kaiser Permanente Research Program on Genes, Environment, and Health (RPGEH). Clin Med Res. 2013;11(3):146 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Cawthon RM, Freiberg JJ, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Short telomere length, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and early death. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(3):822–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett EL, Burke TA, Hammers M, Komdeur J, Richardson DS. Telomere length and dynamics predict mortality in a wild longitudinal study. Mol Ecol. 2013;22(1):249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deelen J, Beekman M, Codd V, et al. Leukocyte telomere length associates with prospective mortality independent of immune-related parameters and known genetic markers. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(3):878–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shalev I, Entringer S, Wadhwa PD, et al. Stress and telomere biology: a lifespan perspective. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(9):1835–1842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Entringer S, Buss C, Wadhwa PD. Prenatal stress, telomere biology, and fetal programming of health and disease risk. Sci Signal. 2012;5(248):pt12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Entringer S, Epel ES, Lin J, et al. Maternal psychosocial stress during pregnancy is associated with newborn leukocyte telomere length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(2):134.e1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunn DA, Murray PG, Tomlin CC, Rexbye H, Christensen K, Mayes AE. Perceived age as a biomarker of ageing: a clinical methodology. Biogerontology. 2008;9(5):357–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uotinen V, Rantanen T, Suutama T. Perceived age as a predictor of old age mortality: a 13-year prospective study. Age Ageing. 2005;34(4):368–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanton WR, McGee R, Silva PA. Indices of perinatal complications, family background, child rearing, and health as predictors of early cognitive and motor development. Pediatrics. 1991;88(5):954–959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckfield PM. Perinatal events in the Dunedin City population 1967–1973. N Z Med J. 1978;88(620):244–246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav. 2012;106(1):29–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molfese VJ. Perinatal risks across infancy and early childhood: what are the lingering effects on high and low risk samples? In: DiLalla LF, Dollinger SMC, eds. Assessment of Biological Mechanisms Across the Life Span. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2013:53 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowtell DD. Rapid isolation of eukaryotic DNA. Anal Biochem. 1987;162(2):463–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeanpierre M. A rapid method for the purification of DNA from blood. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15(22):9611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(10):e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shalev I, Moffitt TE, Sugden K, et al. Exposure to violence during childhood is associated with telomere erosion from 5 to 10 years of age: a longitudinal study. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(5):576–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shalev I, Moffitt TE, Braithwaite AW, et al. Internalizing disorders and leukocyte telomere erosion: a prospective study of depression, generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder [published online ahead of print January 14, 2014]. Mol Psychiatry. doi:10.1038/mp.2013.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson S, Hollis C, Kochhar P, Hennessy E, Wolke D, Marlow N. Psychiatric disorders in extremely preterm children: longitudinal finding at age 11 years in the EPICure study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(5):453–463, e1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan MC, Msall ME, Miller RJ. 17-year outcome of preterm infants with diverse neonatal morbidities: part 1—impact on physical, neurological, and psychological health status. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2012;17(3):226–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Golding J, Kuh D, Wadsworth ME. Growth in utero, blood pressure in childhood and adult life, and mortality from cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 1989;298(6673):564–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardner M, Bann D, Wiley L, et al. Halcyon study team . Gender and telomere length: systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Gerontol. 2014;51:15–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robertson T, Batty GD, Der G, Fenton C, Shiels PG, Benzeval M. Is socioeconomic status associated with biological aging as measured by telomere length? Epidemiol Rev. 2012;35(1):98–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strauss RS. Adult functional outcome of those born small for gestational age: twenty-six-year follow-up of the 1970 British Birth Cohort. JAMA. 2000;283(5):625–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee AC, Katz J, Blencowe H, et al. CHERG SGA-Preterm Birth Working Group . National and regional estimates of term and preterm babies born small for gestational age in 138 low-income and middle-income countries in 2010. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(1):e26–e36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mather KA, Jorm AF, Parslow RA, Christensen H. Is telomere length a biomarker of aging? A review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(2):202–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanton WR, McGee RO, Silva PA. A longitudinal study of the interactive effects of perinatal complications and early family adversity on cognitive ability. Aust Paediatr J. 1989;25(3):130–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foley DL, Thacker LR, II, Aggen SH, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Pregnancy and perinatal complications associated with risks for common psychiatric disorders in a population-based sample of female twins. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105(5):426–431 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen P, Velez CN, Brook J, Smith J. Mechanisms of the relation between perinatal problems, early childhood illness, and psychopathology in late childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. 1989;60(3):701–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beck JE, Shaw DS. The influence of perinatal complications and environmental adversity on boys’ antisocial behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(1):35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lubchenco LO. The High Risk Infant. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rich-Edwards JW, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al. Birth weight and risk of cardiovascular disease in a cohort of women followed up since 1976. BMJ. 1997;315(7105):396–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frankel S, Elwood P, Sweetnam P, Yarnell J, Smith GD. Birthweight, body-mass index in middle age, and incident coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1478–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blackburn EH. Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell. 2001;106(6):661–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waterland RA, Michels KB. Epigenetic epidemiology of the developmental origins hypothesis. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:363–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corsini CA, Viazzo PP. The Decline of Infant and Child Mortality: The European Experience, 1750–1990. Leiden, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aizer A, Currie J. The intergenerational transmission of inequality: maternal disadvantage and health at birth. Science. 2014;344(6186):856–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lander T. Neonatal and Perinatal Mortality: Country, Regional and Global Estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, de Bernis L, Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team . Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet. 2005;365(9463):977–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carlo WA, Goudar SS, Jehan I, et al. First Breath Study Group . Newborn-care training and perinatal mortality in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(7):614–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Biron-Shental T, Sukenik Halevy R, Goldberg-Bittman L, Kidron D, Fejgin MD, Amiel A. Telomeres are shorter in placental trophoblasts of pregnancies complicated with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Early Hum Dev. 2010;86(7):451–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davy P, Nagata M, Bullard P, Fogelson NS, Allsopp R. Fetal growth restriction is associated with accelerated telomere shortening and increased expression of cell senescence markers in the placenta. Placenta. 2009;30(6):539–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Menon R, Yu J, Basanta-Henry P, et al. Short fetal leukocyte telomere length and preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Milne BJ, Moffitt TE, Crump R, et al. How should we construct psychiatric family history scores? A comparison of alternative approaches from the Dunedin Family Health History Study. Psychol Med. 2008;38(12):1793–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Revised. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1974 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 4th ed. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Assessment; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, et al. The p factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clin Psych Sci. 2014;2(2):119–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perloff D, Grim C, Flack J, et al. Human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometry. Circulation. 1993;88(5 pt 1):2460–2470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(9):e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blair SN, Kampert JB, Kohl HW, III, et al. Influences of cardiorespiratory fitness and other precursors on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women. JAMA. 1996;276(3):205–210 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.American Thoracic Society . Standardization of spirometry: 1994 update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(3):1107–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(6):532–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.