Abstract

Candida is the shortened name used to describe a class of fungi that includes more than 150 species of yeast. In healthy individuals, Candida exists harmlessly in mucus membranes such as your ears, eyes, gastrointestinal tract, mouth, nose, reproductive organs, sinuses, skin, stool and vagina, etc. It is known as your “beneficial flora” and has a useful purpose in the body. When an imbalance in the normal flora occurs, it causes an overgrowth of Candida albicans. The term is Candidiasis or Thrush. This is a fungal infection (Mycosis) of any of the Candida species, of which Candida albicans is the most common. When this happens, it can create a widespread havoc to our overall health and well-being of our body.

Keywords: Candida albicans, fungi, yeast, mitosporic fungi, oral thrush, mycosis

INTRODUCTION

Fungi are free-living, eukaryotic organisms that exist as yeasts (round fungi), moulds (filamentous fungi), or a combination of these two (dimorphic fungi). Oral candidiasis is one of the common fungal infection, affecting the oral mucosa. These lesions are caused by the yeast Candida albicans. Candida albicans are one of the components of normal oral microflora and around 30% to 50% people carry this organism. Rate of carriage increases with age of the patient. Candida albicans are recovered from 60% of dentate patient's mouth over the age of 60 years. There are many types of Candida species, which are seen in the oral cavity.[1,2] Species of oral Candida are: C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. guillermondii, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, C. pseudotropicalis, C. stellatoidea, C. tropicalis.[3]

Proposed revised classification of Oral Candidosis[4] Primary oral candidosis (Group I)

-

Acute

- Pseudomembranous

- Erythematous

-

Chronic

- Erythematous

- Pseudomembranous

- Hyperplastic

- Nodular

- Plaque-like

-

Candida-associated lesions

- Angular cheilitis

- Denture stomatitis

- Median rhomboid glossitis

-

Keratinized primary lesions superinfected with Candida

- Leukoplakia

- Lichen planus

- Lupus erythematosus.

Secondary oral candidoses (Group II)

Oral manifestations of Systemic mucocutaneous.

Candidosis (due to diseases such as thymic aplasia and candidosis endocrinopathy syndrome).

RISK FACTORS

Pathogen

Candida is a fungus and was first isolated in 1844 from the sputum of a tuberculosis patient.[5] Like other fungi, they are non-photosynthetic, eukaryotic organisms with a cell wall that lies external to the plasma membrane. There is a nuclear pore complex within the nuclear membrane. The plasma membrane contains large quantities of sterols, usually ergosterol. Apart from a few exceptions, the macroscopic and microscopic cultural characteristics of the different candida species are similar. They can metabolize glucose under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Temperature influences their growth with higher temperatures such as 37°C that are present in their potential host, promoting the growth of pseudohyphae. They have been isolated from animals and environmental sources. They require environmental sources of fixed carbon for their growth. Filamentous growth and apical extension of the filament and formation of lateral branches are seen with hyphae and mycelium and single cell division is associated with yeasts.[6] Several studies have demonstrated that infection with candida is associated with certain pathogenic variables. Adhesion of candida to epithelial cell walls, an important step in initiation of infection, is promoted by certain fungal cell wall components such as mannose, C3d receptors, mannoprotein and saccharins.[7,8,9] Other factors implicated are germ tube formation, presence of mycelia, persistence within epithelial cells, endotoxins, induction of tumor necrosis factor and proteinases.[10,11,12] Phenotypic switching which is the ability of certain strains of C. albicans to change between different morphologic phenotypes has also been implicated.[13]

Host

Local factors

Impaired salivary gland function can predispose to oral candidiasis. Antimicrobial proteins in the saliva such as lactoferrin, sialoperoxidase, lysozyme, histidine-rich polypeptides and specific anti-candida antibodies, interact with the oral mucosa and prevent overgrowth of candida.[14] Drugs such as inhaled steroids have been shown to increase the risk of oral candidiasis by possibly suppressing cellular immunity and phagocytosis. The local mucosal immunity reverts to normal on discontinuation of the inhaled steroids. Dentures predispose to infection with candida in as many as 65% of elderly people wearing full upper dentures. Wearing of dentures produces a microenvironment conducive to the growth of candida with low oxygen, low pH and an anaerobic environment. This may be due to enhanced adherence of Candida sp. to acrylic, reduced saliva flow under the surfaces of the denture fittings, improperly fitted dentures, or poor oral hygiene.[14] Other factors are oral cancer/leukoplakia and a high carbohydrate diet. Growth of candida in saliva is enhanced by the presence of glucose and its adherence to oral epithelial cells is enhanced by a high carbohydrate diet.[14]

Systemic factors

Extremes of life predispose to infection because of reduced immunity. Drugs such as broad spectrum antibiotics alter the local oral flora creating a suitable environment for candida to proliferate. Immunosuppressive drugs such as the antineoplastic agents have been shown in several studies to predispose to oral candidiasis by altering the oral flora, disrupting the mucosal surface and altering the character of the saliva. Other factors are smoking, diabetes, Cushing's syndrome, immunosuppressive conditions such as HIV infection, malignancies such as leukemia and nutritional deficiencies – vitamin B deficiencies have been particularly implicated.[14]

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS OF ORAL CANDIDIASIS

Specimen collection[15]

The specimen should be collected from an active lesion; old ‘burned out’ lesions often do not contain viable organisms.

Collect the specimen under aseptic conditions.

Collect sufficient specimen.

Use sterile collection devices and containers

Label the specimen appropriately; all clinical specimens should be considered as potential biohazards and should be handled with care using universal precautions.

The specimen should be kept moist or in a transport medium and stored in a refrigerator at 4ºC. Due to variety of clinical forms of oral candidiasis, a number of different types of specimens may be submitted to the laboratory.[16]

Smear

Smears are taken from the infected oral mucosa, rhagades and the fitting side of the denture, preferably with wooden spatulas. Smears were fixed immediately in ether/alcohol 1:1 or with spray fix. Dry preparations may be examined by Gram stain method and periodic acid Schiff (PAS) method.[16]

Swabs

Swabs are seeded on Sabouraud's agar (25ºC or room temperature), on blood agar (35ºC), on Pagano-Levin medium (35ºC) or on Littmann's substrate (25ºC). Incubation at 25ºC is done to ensure recovery of species growing badly at 35ºC. Sabouraud's dextrose agar is frequently used as a primary culture medium. Since mixed yeast infections are seen in the oral cavity more frequently than previously thought, particularly in immunocompromised or debilitated patients, Pagano-Levin agar or Littmann's substrate, are useful supplements, because they enable distinction of yeasts on the basis of difference in colony color.[16]

Biopsy

Biopsy specimen should in addition be sent for histopathological examination when chronic hyperplastic candidosis is suspected.[16]

Imprint culture technique

Sterile, square (2.2 × 2.5 cm), plastic foam pads are dipped in peptone water and placed on the restricted area under study for 30-60 seconds. Thereafter the pad is placed directly on Pagano-Levin or Sabouraud's agar, left in situ for the first 8 hours of 48 hours incubation at 37ºC. Then, the candidal density at each site is determined by a Gallenkamp colony counter and expressed as colony forming units per mm2 (CFU mm-2).[16,17] Thus, it yields yeasts per unit mucosal surface. It is useful for quantitative assessment of yeast growth in different areas of the oral mucosa and is thus useful in localizing the site of infection and estimating the candidal load on a specific area (Budtz-Jorgensen, 1978, Olsen and Stenderup A, 1990).[16,18]

Impression culture technique

Taking maxillary and mandibular alginate impressions, transporting them to the laboratory and casting in 6% fortified agar with incorporated Sabouraud's dextrose broth. The agar models are then incubated in a wide necked, sterile, screw-topped jar for 48-72 hours at 37ºC and the CFU of yeasts estimated.[19]

Saliva

This simple technique involves requesting the patient to expectorate 2 ml of mixed unstimulated saliva into a sterile, universal container, which is then vibrated for 30 seconds on a bench vibrator for optimal disaggregation. The number of Candida expressed as CFU/ml of saliva is estimated by counting the resultant growth on Sabouraud's agar using either the spiral plating or Miles and Misra surface viable counting technique. Patients who display clinical signs of oral candidiasis usually have more than 400 CFU/mL.[19]

Oral rinse technique

It was first described by Mckendrik, Wilson and Main (1967) and later modified by Samaranayake et al. (1968).[20]

Paper Points

An absorbable sterile point is inserted to the depth of the pocket and kept there for 10 sec and then the points are transferred to a 2 ml vial containing Moller's VMGA III transport medium, (which also facilitates survival of facultative and anaerobic bacteria).[16]

Commercial identification kits

The Microstix-candida (MC) system consists of a plastic strip to which is affixed a dry culture area (10 mm × 10 mm) of modified Nickerson medium (Nickerson, 1953) and a plastic pouch for incubation. The O Yeast-I dent system is based on the use of chromogenic substances to measure enzyme activities. Ricult-N dip slide technique is similar to, but of higher sensitivity than MC system.[21]

Histological identification

Demonstration of fungi in biopsy specimens may require several serial sections to be cut.[16] Fungi can be easily demonstrated and studied in tissue sections with special stains. The routinely used Hematoxylin and Eosin stain poorly stains Candida species. The specific fungal stains such as PAS stain, Grocott-Gomori's methenamine silver (GMS) and Gridley stains are widely used for demonstrating fungi in the tissues, which are colored intensely with these stains.[17]

Physiological tests

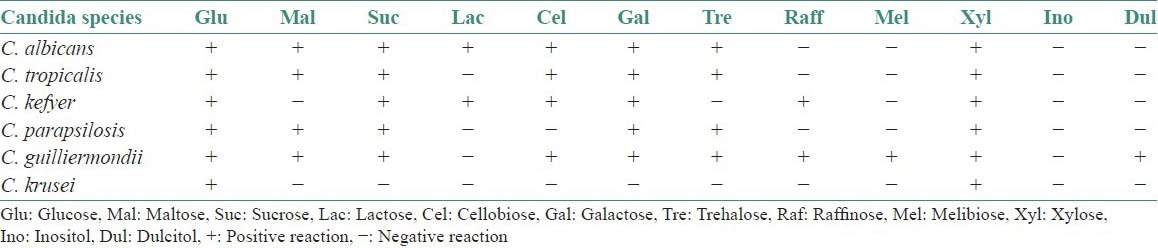

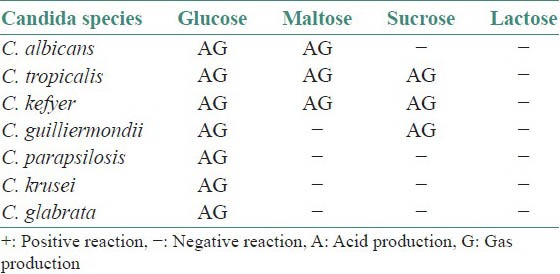

The main physiological tests used in definitive identification of Candida species involve determination of their ability to assimilate and ferment individual carbon and nitrogen sources.[17,22]

The assimilation reactions and fermentation reactions of Candida species are tabulated in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Assimilation reactions

Table 2.

Fermentation reactions

Phenotypic methods[22,23]

Serotyping

Serotyping is limited to the two serotypes (A and B), a fact that makes it inadequate as an epidemiologic tool. It has recently been shown that there can be wide discrepancies in the results obtained with different methods of serotyping,

Resistogram typing

Resistograms do not correlate with pathogenic potential and even though improvements have been made in the method growth end-points often present problems because of inoculum size, interpretation and reproducibility.

Yeast ‘Killer Toxin’ typing

These authors initially used nine killer strains, developing a triplet code to distinguish between 100 strains of C. albicans and found 25 killer- sensitive types. This method was expanded by using 30 killer strains and three antifungal agents, which appeared to discriminate between sufficient numbers of strains of C. albicans.

Morphotyping

This method has been used in a study of the morphotypes of 446 strains of C. albicans isolated from various clinical specimens.

Biotyping

Williamson (1987) has proposed a simpler method. This system comprised three tests, the APIZYM system, the API 20C system and a plate test for resistance to boric acid. This system was found to distinguish a possible 234 biotypes, of which 33 were found among the 1430 isolates of C. albicans taken from oral, genital and skin sites.

Protein typing

Non-lethal mutations of proteins during the yeast cell cycle yield proteins of differing physical properties between strains, which may be distinguishable by one or two dimensional gel electrophoresis. These methods have been used to separate C. albicans at the subspecies level.

Genetic methods

The earliest molecular methods used for fingerprinting C. albicans strains were karyotyping, restriction endonuclease analysis (REA) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). In arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction (AP-PCR) analysis (synonym: randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis), the genomic DNA is used as a template and amplified at a low annealing temperature with use of a single short primer (9 to 10 bases) of an arbitrary sequence.[22]

Serological tests[23]

Serological tests for invasive candidiasis

Detection of antibodies

Slide agglutination

Immunodiffusion

Phytohemagglutination

Coelectosynersis

Immunoprecipitation

A and B immunofluorescence

Nonspecific Candida Antigens

Latex agglutination

Immunobloting

Cell Wall Components

Cell Wall Mannoprotein (CWMP)

b-(1,3)-D-glucan

Candida Enolase Antigen testing.

Immunodiagnosis[17]

The use of specific antibodies labeled with fluorescent stain permits causative organisms to be diagnosed accurately within minutes. However, the preparation of specific antisera and purified polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies entails a much more extensive technical outlay, so the application of these reagents need only be considered when a very precise diagnosis is of therapeutic consequence (Olsen and Stenderup, 1990). The usefulness of antibody testing in the diagnosis of oral candidosis when other simpler, sensitive and reliable techniques are available is questionable (Silverman et al., 1990).

MANAGEMENT[4]

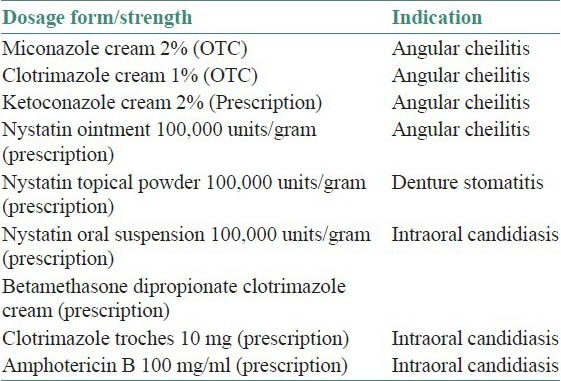

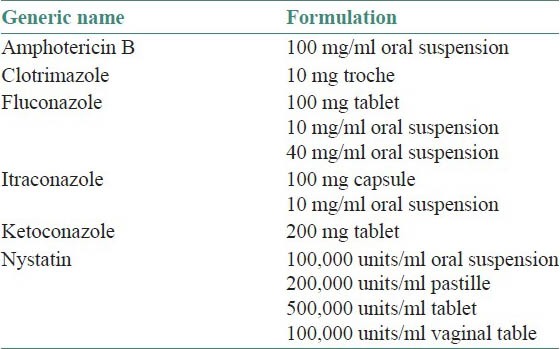

Assessment of predisposing factor plays a crucial role in the management of candidal infection. Mostly the infection is simply and effectively treated with topical application of antifungal ointments. However in chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis with immunosuppression, topical agents may not be effective. In such instances systemic administration of medications is required [Tables 3 and 4].[4]

Table 3.

Topical antifungal medications[4]

Table 4.

Systemic antifungal medications of oropharyngeal candidiasis[4]

CONCLUSION

Yeast-free diets, or people, are both impossible to come by. They can only be totally avoided in the diet by eating solely fresh dairy, meat, fish and peeled fresh fruits and vegetables. From a practical standpoint, this is neither feasible nor necessary. Total elimination of yeast from the body is also neither feasible nor desirable, considering that yeasts are beneficial to the body when a proper balance exists. Treatment of candida overgrowth does not seek the eradication of candida from the diet or the person, but rather a restoration of the proper and balanced ecological relationship between man and yeast.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Terezhalmy GT, Huber MA. Oropharyngeal candidiasis: Etiology, epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Crest Oral-B at dentalcare.com Contin Educ Course. 2011:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prasanna KR. Oral candidiasis – A review. Scholarly J Med. 2012;2:6–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dangi YS, Soni MS, Namdeo KP. Oral candidiasis: A review. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2010;2:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parihar S. Oral candidiasis- A review. Webmedcentral Dent. 2011;2:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994. Anti-fungal agents; pp. 401–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehmann PF. Fungal structure and morphology. Med Mycol. 1998;4:57–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brassart D, Woltz A, Golliard M, Neeser JR. In-vitro inhibition of adhesion of Candida albicans clinical isolates to human buccal epithelial cells by Fuca1 ® 2Galb-bearing complex carbohydrates. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1605–13. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.5.1605-1613.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghannoum MA, Burns GR, Elteen A, Radwan SS. Experimental evidence for the role of lipids in adherence of Candida spp to human buccal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1986;54:189–93. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.1.189-193.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas LJ. Surface composition and adhesion of Candida albicans. Biochem Soc Trans. 1985;13:982–4. doi: 10.1042/bst0130982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobel JD, Muller G, Buckley HR. Critical role of germ tube formation in the pathogenesis of candidal vaginitis. Infect Immun. 1984;44:576–80. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.3.576-580.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saltarelli CG, Gentile KA, Mancuso SC. Lethality of candidal strains as influenced by the host. Can J Microbiol. 1975;21:648–54. doi: 10.1139/m75-093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith CB. Candidiasis: Pathogenesis, host resistance, and predisposing factors. In: Bodey GP, Fainstein V, editors. Candidiasis. New York: Raven Press; 1985. pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slutsky B, Buffo J, Soll DR. High frequency switching of colony morphology in Candida albicans. Science. 1985;230:666–9. doi: 10.1126/science.3901258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akpan A, Morgan R. Oral candidiasis. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:455–9. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.922.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epstein JB, Pearsall NN, Truelove EL. Oral candidosis: Effects of antifungal therapy upon clinical signs and symptoms, salivary antibody, and mucosal adherence of Candida albicans. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981;51:32–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(81)90123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsen I, Stenderup A. Clinical – mycologic diagnosis of oral yeast infections. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990;48:11–8. doi: 10.3109/00016359009012729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverman S., Jr . Laboratory diagnosis of oral candidosis. In: Samaranayake LP, MacFarlane TW, editors. Oral Candidosis. 1st ed. Cambridge: Butterwort; 1990. pp. 213–37. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Budtz-Jorgensen E. Clinical aspects of Candida infection in denture wearers. J Am Dent Assoc. 1978;96:474–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1978.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein JB, Pearsall NN, Truelove EL. Quantitative relationships between candida albicans in saliva and the clinical status of human subjects. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;12:475–6. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.3.475-476.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samaranayake LP. Nutritional factors and oral candidosis. J Oral Pathol. 1986;15:61–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1986.tb00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cutler JE, Friedman L, Milner KC. Biological and chemical characteristics of toxic substances from Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1972;6:616–27. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.4.616-627.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandven P. Laboratory identification and sensitivity testing of yeast isolates. Acta Odontal Scand. 1990;48:27–36. doi: 10.3109/00016359009012731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCullough MJ, Ross BC, Reade PC. Candida albicans: A review of its history, taxonomy, epidemiology, virulence attributes, and methods of strain differentiation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;25:136–44. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(96)80060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]