Abstract

Adversities facing people with disabilities include barriers to meeting daily needs and to social life. Yet, too, fundamental social devaluation erodes an individual’s capacity to retain title to the cultural category of a full person. These cultural adversities are important components in the disablement process. The cultural meanings for physical dependency convey images of childlike, dependent, incomplete persons near death. Using interviews with middle aged and elderly polio survivors, the author identifies key cultural categories, the expectations and values linked with disability and describe the strategies people use to confront, or not, the erosion of personhood. The importance of understanding the category of the person, its historical setting, and evolution are highlighted. Finally, the inversion of traditional cultural logics for defining the personhood of individuals with disabilities is illustrated.

Severe physical impairments pose a host of hardships, some of which are more obvious than others. Impairments limit the ability to do basic daily tasks that sustain the body and the spirit. Eating, moving around, bathing, and taking part in valued personal and social life through holding a job and leisure activities all require extra efforts. Being unable to perform valued activities fosters social devaluation and low self-regard. Yet, the social devaluation is corrosive to people with disabilities at a more implicit cultural level.

One of the cultural consequences of having disabilities is that an individual’s identity as a complete person comes into question rather than remaining taken for granted. Being unable to fully perform normatively valued activities and roles in the workplace, home, and community challenges an individual’s core identity as a full adult person. The erosion of personhood that is associated with disability is a cultural level adversity that is not well understood. The aim of this article is to examine and illustrate these issues. It will contribute an understanding of individual values, motivations, and actions as situated within an ecology of cultural contexts one of which is the category of personhood. To begin, basic concepts and orientations need to be made explicit.

BASIC ORIENTING CONCEPTS

The Person as a Cultural Construct

The category of the “person” is found in all societies, but the identities and capacities that make it up are culture specific (Geertz 1984; Hallowell 1955; Shweder and Bourne 1984). Personhood is bestowed by society, and is earned by achieving and maintaining expected social roles and ideals. It is not an intrinsic property of the individual nor can it be seized merely by individual fiat (Fortes 1987; Schiebe 1984). By person I refer to the cultural category of full adulthood or full personhood. The term individual is used to refer to the concrete biological organism. Personhood is not an automatic or intrinsic property of the individual nor can it be gained by personal claim—it must be socially legitimated. For example, in America when a baby leaves its mother’s body at birth it is recognized as a person as we grant official places for them in society by assigning family and personal names, federal social security numbers, and legal rights (yet exercised in proxy by the parents until legally defined adulthood is achieved). But we watch eagerly for the baby to become more of a “real” person as they come to master the movement of their arms and legs, demonstrate awareness of people, and begin to speak.

In American society full personhood is earned during the adult phase (thus, adulthood is used synonymously with personhood here) of the life course by being a responsible and (re)productive worker, spouse, family and community member. One must both achieve entry to and remain competent in these areas in order to be socially recognized as a full adult. For example, individuals who are unemployed, disabled, or childless may be stigmatized and share a sense of not being a complete person. Further, the cultural life course provides a shared timetable for evaluating how “on-time” (Seltzer and Troll 1985) social achievements are from birth to death. Thus, the impact of disabilities on adulthood must be interpreted in at least two contexts: the timeliness or age appropriateness of being “less independent” to the life course stage; and the wider cultural criteria and meanings as a full person.

The scientific community is split as to whether, in theory, the category of full person is fixed once achieved, or if it can be retracted. In the case of people with disabilities or the elderly there appears to be evidence that it is diminished. Certain categories of persons are held in lower esteem1 and their legal and moral autonomy and recognition as self determining individuals is abridged. These categories include, for example, people with dementia, physical disabilities that prevent communication, or people whose failure to uphold social norms and expectations results in moral and legal sanctions. In the later instances, citizens convicted of capital crimes and treasons are deprived of their liberty of free movement and free association by imprisonment or even death. Even though there is some distinction between those who willfully break social norms (thus the recent emergence of the ‘temporary insanity defense’) and those whose physical condition stymies their ability to meet expected social behaviors, both are deprived of recognition as culturally competent and complete persons.

Two Perspectives: Disability and Disablement Processes

A core social science paradigm has evolved from questioning how the larger macro level contexts of community values, beliefs, and institutions, influence the micro level of a person’s self-image, sense of opportunities and limits, behaviors and daily experiences. Studying how macrolevel cultural and community ideologies shape the microlevel of individual life follows a long tradition exemplified by Margaret Mead, Max Weber, Robert Merton, Talcott Parsons, and disability studies by Davis (1961, 1963), Edgerton (1967), Estroff (1982), and Murphy (1987). For example, Stouffer’s (1949) pioneering survey method revealed that American soldiers in World War II responded to the shared adversity of combat differently according to personal expectations based on sociocultural value patterns and lived experiences, thus illustrating Merton’s theories of relative deprivation and reference groups and also revealing the interaction of macro and micro level processes.

These early insights become even more relevant to contemporary issues of aging with disabilities. Stigma (Goffman 1963) is a classic model of culturally patterned meanings that instill deep feelings and motivations in individuals by the ascription of devalued social identities and social patterns of avoidance and denigration. Whereas psychological approaches have tended to explore the feelings of shame, low self-esteem, and withdrawal, social sciences have highlighted the societal values and patterns of treatment of people with visible disabilities. Later some of the interactions between the macro cultural level and individual’s views about the conditions of living with impairments are illustrated.

DISABILITY

The World Health Organization nomenclature (Wood 1980; but cf. IOM 1991) defines impairment as the loss of physical function, and disability as a limited ability to perform activities. Handicap refers to problems caused by the disability in a given society. Thus, an accident may limit a person’s ability to use their legs (the impairment) to climb stairs (the disability). The social fall-out is that employers refuse to hire the person (the handicap). This article focuses on one important handicap consequent to disability, the erosion of adult personhood.

As an anthropologist studying culture, I argue that the implications of disabilities at the cultural level of personhood are crucial to the tenor of the personal experience and social patterns of treatment of individuals with impairments. These implications are important in two ways. Individual efforts to cope with disability focus on preserving one’s identity as a complete person as well as managing functional limititations and social activities. The ability to successfully manage threats to adult identity contributes to an individual’s willingness and motivation to marshal personal and social resources to overcome impairments and regain functioning in daily activities.

Multiple meanings are attributed when an individual’s physical movement appears to be limited. In America activity is an ethic and a sign of health and well-being; inactivity is interpreted as a sign of passivity, distress, or depression (by those with and without disabilities alike). Consequently, for someone with functional impairments, movement may be an unreliable indicator of passivity or symptom of distress. Walking off in a huff or other bodily self-expressions are not possible as an outward sign of engagement and pleasure or displeasure with life. Notably, recognizing that somatic and behavioral symptoms are ambiguous as signs of depression among people with health problems, mental health researchers (Rapp and Vrana 1989; Koenig et al. 1992) are revising diagnostic scales to control for such ambiguities when assessing elderly and disabled people.

Most disability research treats the individual as the basic unit of analysis. The current research on disability concentrates on individual stress, coping, and adaptations and on the social situations and lived experiences of impairments. Yet, extending our insights into the cultural construction of disability is a priority because we know that cultural beliefs and values instill powerful motivations and experiences that shape how individuals make sense of and deal with disabilities. Thus, currently we lack a well developed understanding of the handicap of diminished adulthood, that is, the erosion of public recognition as a complete human person which occurs when one cannot carry out typical daily activities and social roles.

From a cultural view, the loss of independent motor control degrades one’s position as a full adult person. Indeed there is a dehumanization, an unraveling of the lifelong competences that in earliest childhood marked the emergence of a full person: the acquisition of language and independent willful movement of the body by walking. That is, the association of old age and senility with disability taints the public image of adults with disabilities at all ages. Trenchant popular stereotypes of old age as haunted by the specter of illness and death, set the stage for disabilities at mid and late life to pose acute challenges to self-esteem and to the individual’s credibility as a complete person who exercises competent, rationale, independent judgments and actions.

DISABLEMENT PROCESSES

With the advent of refined conceptual frameworks for understanding disability (cf. IOM 1991; NICHD 1993; Verbrugge and Jette 1993; Wood 1980) a consensus has emerged that the brute facts of physical function (heart and lung capacity, muscle strength, walking speed) dictate neither disability nor handicap. Instead, it is the social and personal interpretation of impairments in light of shared values, expectations, and ideals that produce experiences and patterns of limitations in daily lives. The concept of “societal limitations” is gaining wider acceptance. It refers to “restrictions attributed to social policy or barriers (structural or attitudinal) which limit fulfillment of roles or deny access to services and opportunities associated with full participation in society” (NICHD 1993). Verbrugge and Jette (1993) propose we adopt the term disablement process, widespread in European science and policy, into American discourse in place of disability in order to emphasize the social and processural dimensions. The current dearth of knowledge about these processes is illustrated, for example, by Verbrugge’s (1992) longitudinal studies of arthritis. They revealed how after the onset of the pain and limited joint functioning, the decline in abilities to walk and do daily activities was followed within two years by improved functioning at daily activities as people accommodated to the impairments (e.g. using adaptive equipment, help from other people, and choosing new activities). That is, the level of disability diminished even as the arthritic impairments remained. Studies of perception and management of the sociocultural domain of personhood can contribute to models of the disablement process by expanding the focus to include cultural categories.

The inability to carry out socially expected activities and roles in the work-place, home, and community diminishes one’s standing as a full adult person. One result is a loss of public value and prestige in the community. Cultural images for incapacity and dependency convey meanings of being childlike dependent, incomplete persons, sometimes referred to as infantilization of the disabled and aged. The American cultural logic that equates disability with developmental and social immaturity reflects the assault on the core features of adult persons. In combination, internalization of these negative judgments and images produces feelings of low self-esteem and what Robert Murphy (1987) labels “impetuses to withdraw” in isolation and passivity or hopelessness. It is precisely these cultural images that motivated disability activists to advocate removing the phrase “the disabled” in favor of “people with disabilities” to emphasize the person instead of the limitation. Again, I point to the value of understanding the implications of disabilities for retaining full adult personhood as a vital part of the experience and social patterns of treatment of people with impairments.

This article will describe sociocultural implications of functional impairments for the category of full personhood. It develops understandings of the cultural construction of individual experiences of “personhood” from the view of the people with disabilities, and the strategies people use to confront, or not, the erosion of adulthood. Examples and illustrations are presented from interviews with adults aging with disabilities at mid and late life following childhood polio. The focus here is on the cultural category of adulthood rather than the lived experiences and personal impact of diminished adulthood. Researchers have described the parallel processes of personal biography, psychosocial development and the life course for people with disabilities (Bury 1982; Kaufert and Locker 1990; Scheer and Luborsky 1991).

Evolving Concepts of the Adult Person: Questioning Concerns About Personhood

The concept of the person structures and informs our descriptions but also the particular ways in which it is defined has shaped gerontology’s recognition of threats to personhood. At the same time that we examine challenges to personhood we must ask how the challenges we see are a by-product of a particular construction of the “person” itself. The definition of persons and their capabilities is inseparable from wider sociopolitical times (Luborsky and Sankar 1993). Intrinsic to the guiding question for the collection of articles in this issue, threats to adult identity, is a historical set of concepts about society and the person (cf. Dumont 1986; Ortner 1984; White and Kirkpatrick 1985). These underlying concepts structure the nature of which questions and topics are formulated for assessments (cf. Luborsky 1990). That is, the nature of the “threat” is tied to our concept of adulthood, as much as it is discovered by talking with research participants. A clearer understanding of these underlying concepts, or biases, can suggest new areas for research and measurement. These underlying frameworks are broadly summarized next.

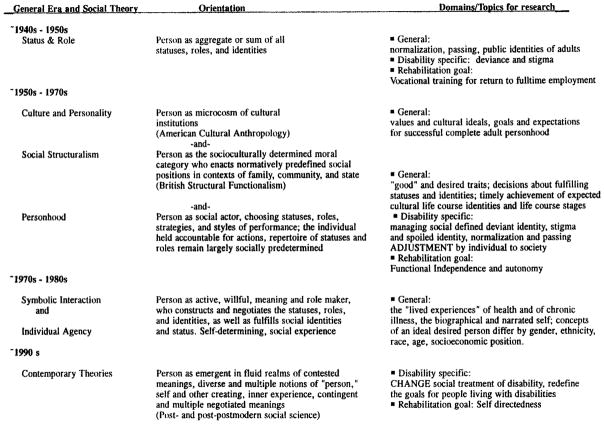

Several major social theories informing concepts of the person emerged in our century. These are summarized in Figure One by reading across the table from left to right for each major era. We see first the major social theories, then the basic orientation it provides to conceptualizing “full adult persons,” and examples of the domains or topics for research suggested by the theoretical orientation. These major orientations and topics can be seen to structure the literature on the psychosocial impact of disability. They also are associated with shifts in rehabilitation goals and practices. For example, the 1950’s view of persons as simply determined by the sum of their public statuses and roles framed views of those who are unable to fulfill these statuses as “disabled people,” socially deviant and stigmatized. Rehabilitation was directed to full recovery defined as a return to prior capabilities and to the role of fully employed adult, even when severe impairments remained (Gritzer and Arluke 1985; Scheer and Luborsky 1991). These goals partook of the wider national ethos of the Post-Depression and Post War era of economic rebuilding. In contrast, rehabilitation goals shifted in the next era to recovery to autonomous independent functioning (without’ adaptive equipment or personal assistants), but without the focus on return to full employment. In the next era, the ideal of self-directedness in daily life emerged which shifted the onus away from defining independence as autonomous unaided functioning. Each goal shift is set within evolving sociohistorical conditions and social science theoretical frameworks that have evolved from an overdetermined view of the person as a collection of normative social structural statuses to an overly self-determining individual actively constructing experiences and forms of social life.

FIGURE 1.

Views of Personhood: Overview of Evolving Theory, Orientations, and Research Domains

The relevance of this generalized figure is twofold. It points out how each theory directs our attention to certain arenas but also invokes earlier notions underlying the current focus on lived experience and diversity. It suggests the current notion of a “person” builds on rather than replaces prior orientations in an evolving manner. For example, while studies that derive their theoretical approach to measurement from symbolic interaction or agency theory add data on how people negotiate and create identities, the particular identities negotiated tend to be those posited by the antecedent social structural theories. Thus contemporary social activists and research now decry practices from prior decades of the over-generalization of diverse people with impairments under the simplistic label “The Disabled” and rail against “identity spread” (Strauss et al. 1984; Wright 1983) where the one trait of physical impairment stands as a “master identity” (Conrad 1987) instead of a broader vision of the person as comprised of many activities and as self-defining (no longer defined solely and narrowly by normative work inability) and as contesting norms.

A second relevance of Figure One is to highlight an underexamined dynamic. The dynamic nature of “context” over the lifetime suggests that ideas about what is basic to full personhood and the implications of one’s physical and social condition evolve in tandem but somewhat separate from the individual’s life experience and psychosocial developmental related concerns. The wider established historical, rehabilitation, and health care systems contexts are continually challenged and evolve within the informants’ own lifetimes. For example, informants readily remark on the changes in legal and public treatment (cut out curbs for wheelchairs, reserved parking areas) accorded people with disabilities over the span of their lifetime. This brief summary serves to set the background to the next section.

DISABILITIES AS THREATS TO FULL PERSONHOOD

Disability may erode adulthood in at least two ways as highlighted by the outline of theoretical orientations to the person. First, I describe the concerns about personhood voiced by individuals with disabilities and the respective management strategies. In particular, I illustrate several of these domains: core statuses and identities needed to earn and retain full personhood; symbolic interaction by autonomous, willful social agents; and cultural meaning and self creating individuals. Second, I describe how the usual cultural logic by which a person is defined is reversed entirely in the case of disabilities.

Individual’s Concerns about Personhood

The social stigma embodied in denigrating labels and treatment of people who are visibly different or deviate from norms for behavior and appearance (Murphy 1987; Zola 1982) patterns behavior and personal experience. A powerful motivation is the desire to avoid social stigma and to preserve one’s image as a whole person and self-esteem and prestige. Among the choices are either to increase the visibility of being different or to abstain from interaction and become a non-person. Withdrawal or avoiding social activities and roles (becoming an invisible person) is one strategy, another is to acknowledge the visible differences. In order to remain in the roles and identities vital to adulthood people may adopt strategies of passing, denying problems, or withdrawing from situations where they are visibly disabled. What has traditionally been viewed as psychological coping mechanisms needs to be viewed doubly as addressing cultural concerns. The management strategies for impairments and disabilities may focus on remedying cultural level handicaps. That is, in addition to solving instrumental needs in daily life coping strategies may serve to redress threats to adulthood. Different focuses for management strategies highlight different models of the person.

For example, the technological development of portable ventilators promised ventilator-dependent home-bound polio survivors enormous liberties in freedom to travel outside the home. Tellingly, people with lifelong respiratory impairments from polio often chose not to adopt the new technology that allowed independent mobility. The reasons they offered hinged on wishes to avoid becoming more visible in their impairment, this despite the enormous gains in social life outside the home (Kaufert and Locker, 1990). Instead they chose to alter their lifestyle and dramatically compromise opportunities for social interactions. Clearly, concerns with social denigration and marginality pervaded users’ interpretations. We must understand such “motivational” factors are not inherent traits of the person, nor of the assistive device, nor the physical impairment (Luborsky 1993). Rather it derives from the social contexts and cultural implications of their usage. In these contexts people who rely on respiratory equipment for life-support are responding to immanent social categorizations as incomplete “bionic” or hybrid persons.

Robert Murphy (1987) argues that experiencing disability heightens awareness of an erosion of the continuity in one’s habituated ways of making personal meanings and demonstrating competence as a full person. The awareness taps two realms. One realm Murphy identifies is the dialectic between urges for withdrawal and for engagement at several levels of being: the body and its relationship to self-awareness, to self, and society. The other level of withdrawal Murphy identifies is from possibilities for becoming. This focuses on the intended (Shweder 1991) and socially expectable (Neugarten and Hagestadt 1976; Seltzer and Troll 1985) selves and life worlds each vested with a teleology for continued development of the self and social life. The other realm is one of cultural inversions to fundamental logics for defining the self, guilt, and states of mind.

Being in the world with disabilities is an experience permeated by impulses to withdraw or sequester (Murphy 1987, p. 109ff) oneself from others, and to sequester one’s sense of self from the body—”separated from others, and riven from within” (Murphy 1987, p. 227). Here Murphy treads the paths of earlier sociologists (Bury 1982; Davis 1963; Strauss et al. 1984). The impetuses to withdraw and ennui (Murphy 1987, p. 89) are both intended and unintended, both self and other motivated.

Grappling with separation and withdrawal from taken-for-granted public identities is an ongoing process. Desires to withdraw are further motivated by the sociocultural contexts of American life which values independent movement and upright stature (Stein 1979, 1989; Murphy et al. 1988) as reflected in patterns of avoidance, denigration, and ascriptions of spoiled identities to the disabled.

The sense of Becoming for people living with disabilities is an entirely different realm of experience. Simply stated, the onset of bodily impairments transforms daily life experience by closing off a wide array of potential futures and selves. It also redefines the retrospective meanings of earlier events and identities that validate present identity and achievements. For Murphy, disability is a frontal attack on his potential or future possibilities, not just his earthly body and the three different dimensions of body-selves. The existential burden of impairment is attributed to obsolescence of expectable possibilities in the three dimensions of body-selves. Becoming dislocated from the life one expects or desires to live is profoundly disturbing with or without disabilities, striking at the heart of the psyche that animates the culturally defined vessels and bodies of mindful persons (Shweder 1991). Sustaining a perception of personal continuity (Antonovsky 1987; Becker 1993; Cohler 1991; Luborsky and Rubinstein 1987, 1990; Neugarten and Hagestad 1976; Schiebe 1984) including the search for an encompassing ontology (Bury 1982) is important to functioning across the lifespan.

Murphy’s account of “being in the world” with disabilities documents how his sense of the present is enmeshed with the past and possibility of several futures. That is, the self is sensed as a seamless flow of past-present-future(s) that includes the impact of impairments on the unfolding of body conditions based on present and future biographies. Disabilities put into question, retrospectively, the meanings of past events and experiences in light of the present and future lived experiences. These implicit developmental or teleological perspectives are key to the interpretive framework offered by a tripartite view of biological-personal-social features of disability experience.

Cultural Inversions

The second major aspect of disability is one of living in a society that fundamentally reverses the customary direction of attributing meaning. Robert Murphy’s outstanding monograph on the meaning and experience of disability draws from his own experiences with a benign spinal tumor that produces progressive paralysis. He argues that a fundamental inversion in cultural factors is at the core of the construction of disability experiences. In American culture there is

a causal chain that goes from wrongful act to guilt to shame to punishment. A fascinating aspect of disability is that it diametrically and completely reverses the progression while preserving every step. The sequence of the person damaged in body goes from punishment (the impairment) to shame to guilt, and finally to the crime. This is not a real crime but a self-delusion that lurks in our fears and fantasies, in the haunting never-articulated question: What did I do to deserve this?

In this topsy-turvey world of reversed causality, the punishment—for this is how crippling is unconsciously apprehended—begets the crime. All of this happens despite the fact that the individual may be in no way to blame for his condition (Murphy 1987, p. 93).

Such cultural inversions seem widespread. The status of the body switches from being a silent integral background for personhood and the self to become a foreground external feature of constant awareness. The basis of one’s social identity switches from achievements, roles and identities to the fact of physical inability so the impairments become a “master identity” (Conrad 1987; Wright 1983) subordinating all abilities. The social meanings communicated by body posture and movement (to others and yourself) can be misleading. For example, I pointed out above how reduced physical activity may be misinterpreted as a sign of passivity or depression.

Cultural Emphasis on Disability Devalues Competences, Autonomy, and Achievements

Normalizing personhood eroded by disabilities can be pursued by persevering in social roles and using the work ethic. Mr. Ascher is a successful lawyer and father in his middle 40’s. Since a childhood bout with polio he has used a brace and crutches. Recently, due to renewed weakness, fatigue, and pain, he started to use a wheelchair for long distances, upon the doctor’s advice. The advantages of being less tired are far outweighed by the public consequences of using a wheelchair,

Yes there are a lot of losses. And some gains: you can go faster than most people and carry more stuff with you. I do what I’m supposed to do because I’ve been to the clinic and I know what’s wrong with me and what has to be done. [But] I have to … defend my cases in court from a wheelchair and feel diminished in stature.

Mr. Ascher resolved the dilemma of private physical discomfort and limitation but that resolution fostered another dilemma at the level of visible social discomfort and limitation. Ascher’s decision to focus on managing functions and roles core to full personhood required he find a way to keep his job to maintain his status as an upright citizen. But his impaired functioning diminished his stature and ability to perform the roles, as an active, up-right person.

Ms. Darnoff relies on a wheel-chair to travel in her apartment building for independent living elderly at a large geriatric center. In her own apartment she gets around on leg-braces and crutches. She has used adaptive devices her entire adult life. Palpable animosity from other residents is clear when they speak out at the sight of her using a wheel-chair because wheel-chair users typically live in the nursing home. She reported that when she enters the dining room for meals,

they tell me, “you can’t come in,” they don’t want a wheelchair around them. So I go early or late. People feel a wheelchair is the last thing. They can walk with a walker, a cane or be blind. But when you are with a wheel-chair you just don’t belong here. People resent it and they don’t make any bones about it.

The standard categories associated with persons at the geriatric center do not fit Ms. Darnoff. She is anomalous by being neither frail nor feeble (physically or cognitively) nor having an attendant dress, feed, and manage her daily activities. Elderly residents who use wheelchairs generally cannot fend for themselves and are placed in the nursing home section. In fact, her continued residence in the independent apartment building depends on her ability to use crutches to walk in and out of the dining hall without the wheel-chair. Thus, her lifelong expertise using the device and the stability of her condition are obscured by the institutional regulations.

Clearly, using a wheel-chair in this local environment denotes a very different constellation of social and physical meanings. Mrs. Darnoff must continually assert the distinctiveness of her current use of devices in lifetime perspective, and demonstrate she is exceptionally more self-directing and independent than any other wheel-chair user on the geriatric center campus. While the devices help her function independently and thus maintain broad cultural values, they simultaneously define her in the local setting as a less complete person by virtue of requiring help and being visibly different. The multiple and conflicting nature of cultural values is highlighted by Ms. Darnoff.

Mrs. Kruschiak, in her late 50’s, is in her second marriage. She told me a local reporter interviewed her about the experience of her new symptoms of post-polio syndrome. The reporter told her “that’s no big deal” upon learning that Mrs. Kruschiak now needed to use an electrically powered wheelchair. The reporter asked if Mrs. Kruschiak could refer her to someone who was “really bad off.”

Mrs. Kruschiak had severe bulbar and spinal polio as a child. The prognosis was, in her words, “lifetime confinement to a wheelchair.” The wheelchair embodied her future permanent state of immobility. In fact, she was discharged in a wheelchair with no push rims since she was thought to be too weak to ever use them.

A theme in her life story narrative was how by heroic perseverance she and her family transformed the adaptive devices, tangible symbols of the medical decree of extreme disability, into transitional objects which were subsequently discarded along with her medically defined destiny and identity. She asserted an individual destiny and achieved able-bodiedness instead of an identity as disabled. At her best after polio she walked with leg braces and a cane. The continuing non-use of the chair was seminal to her sense of being a complete person and her “normalized” vigorous life of active employment and marriages. For example, during the decades of her stable physical functioning she would tell strangers she broke her leg skiing instead of saying she had polio.

After 25 years the stability of her functioning began to decline into chronic polio late effects, but she ignored the new symptoms that included pain, fatigue, and muscle-soreness and spasms. She finally sought medical help but the physician told her the soreness was a “charley horse,” the fatigue due to a cold or depression. There was no medically defined post-polio syndrome at that time. Finally she had a catastrophic failure. Her legs collapsed after being unable to climb the one flight of stairs to a friend’s house. Lying there, she cried for over an hour, “hysterical and terrified” in her words, that despite years of struggle she could no longer be the same kind of person.

Echoing Murphy’s (1987) dictum about the onus of losing one’s future, she was forced to re-adopt a wheel-chair, and the odd mixture of mobility improvements and restrictions it entailed. She found many of her dearly held personal meanings and public image as a person tarnished, as discussed in the preceding examples. Especially painful was her loss of earlier life achievements and refutations of medically defined destiny. It is important to note that the devices represented a broader sense of loss, not just of physical function, but of a spectrum of cherished patterns of activity, sentiments, and ways of life. Thus, the prescription for use of a new device carries lifespan personal connotations in addition to the sociocultural labels and meanings.

Adopting an electric wheel-chair also reintroduced the prior “destiny” as defined by the medical establishment during the earlier acute phase. Her ability to control her body and social definitions of herself are eroded. To conclude, the reporter’s remark flatly revoked the social “invisibility” (Becker and Kaufman 1988) achieved by rehabilitation. This example also suggests that social contexts continue to minimize the personal experience of loss, not fully validating the extent of the loss experienced, just as her earlier gains were minimalized when the community defined her in light of the disability rather than recovery.

REFLECTIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The cultural adversity that physical disability poses for full personhood is a promising area in need of further study. This article highlighted an implicit cultural dimension of the disablement process, the handicap of eroded recognition as a full adult person caused by physical impairment and social disability. Using case examples I illustrated the salience to individuals of the social limitations imposed by diminution of their public recognition as full adult persons and outlined some of the tactics they use to redress these losses. The social consequences of impaired functioning for personhood in old age is especially acute since it is, in the popular view, linked to the last stage in the life course before death. The manifestations of loss of competent and independent motor control, reason, and speech are akin to the stereotypic view of the senility that precedes death in the popular imagination.

There is a glaring diversity in the cultural logics by which personhood is constructed. For people who have functional impairments, those impairments take over and come to stand for the whole person. Previous achievements and other statuses and roles are not given as much weight. Further, there is a diversity and complexity in the meanings and consequences of management strategies: solving problems at one level raise problems at other levels. For example, improvements from a biomechanical and functional point of view (e.g., ventilators and wheelchairs) pose other harsh handicaps at the level of being a complete culturally defined person.

Contemporary behavioral research and discourse mistakenly equates studies of individuals with issues of subjectivity and psychological issues. Multiple in-depth interviews and case studies are seen by many qualitative and quantitative researchers as best suited to evoke for the public record information on the phenomenology of personal experience and the individual voices of under-represented social experiences. In our decade, one fundamental advance has been to show that subjectivities are not determined solely by major social forms of social organization and life (e.g. class, gender, income). In fact, major contributions in the history of social sciences have been to trace out the myriad ways that wider cultural and social contexts pattern experiences and interests of individuals and groups. We need to remain attentive to analytic complacency in research that equates individuals with subjective and psychological phenomena and that does not account for the mutual interplay between individuals and macrolevel cultural contexts.

The discussion in this article focused on the cultural context of individual lives. Yet, collective actions are another major avenue for addressing socially devalued identities. Individuals may engage in social transformations of the basic value systems that define them as undesirable or incomplete. Social movements often emerge from conditions of social and physical deprivation. Here, social scientists have identified both redemptive movements, those that seek to reaffirm and revitalize traditional values and demonstrate the individual’s allegiance to core cultural values, and transformative movements, those that seek to transform and redefine society. The Disability Rights movements and mental health consumer movements are transforming contemporary American society (e.g. the Americans with Disabilities Act, and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, NAMI). This is important as a means of changing the experiences of diminished adulthood. That is, the disabled are seen as somehow responsible for their impairments and living conditions. At a deep level there is a bias that either they are culpable for the cause of the impairment, or for not working harder at rehabilitation to be able to “overcome” the odds regardless of how realistic that is.

In closing, I have worked to highlight an implicit cultural dimension of the disablement process, the erosion of adulthood associated with disability. In the languages of behavioral and medical research the cultural denigration of full adult personhood is a predisposing context and extra-individual environmental demand that contributes to the impact and outcome of physical impairments. I argue that it is important to extend further research and conceptualization into these cultural domains in order to refine current models of disability and the disablement process. Much more work remains to be done to provide a rigorous view of individual values and motivations as set within an ecology of cultural contexts in which the category of personhood is situated.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (#1RO1 HD31526) to the author. Research was supported by a grant to the author from NIMH (#2PO1AG03934). The author wishes to thank Jessica Sheer for her comments.

Footnotes

It is important to distinguish social esteem or prestige from the cultural category of personhood. Prestige or esteem is based on the relative social desirability or rank of roles and identities within a society, as for example the different social prestige of various jobs or relative value given to people of different ages or wealth. In contrast personhood is the underlying cultural category of a complete human being who may hold various identities and statuses. While animals or business corporations are granted partial personhood by being given a name or held liable for their behavior, they are not full persons.

References

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the Mysteries of Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. Continuity After a Stroke: Implications of Life-course Disruptions in Old Age. The Gerontologist. 1993;33(2):148–158. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G, Kaufman S. Old Age, Rehabilitation and Research. The Gerontologist. 1988;28:459–68. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury M. Chronic Illness as Biographical Disruption. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1982;42:167–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohler B. The Life Story and the Study of Resilience and Response to Adversity. Journal of Life History and Narrative. 1991;1(2&3):169–200. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad P. The Experience of Illness. In: Roth J, Conrad P, editors. Research in the Sociology of Health Care. Vol. 6. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Davis F. Deviance Disavowal. Social Problems. 1961;9(2):121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Davis F. Passage Through Crisis: Polio Victims and Families. New York: Bobbs-Merrill; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont L. Essays on Individualism, Modern Ideology in Anthropological Perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton R. The Cloak of Competence. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Estroff S. Making It Crazy. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Fortes M. Religion, Morality and the Person. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. From the Natives Point of View: On the Nature of Anthropological Understanding. In: Shweder R, LeVine R, editors. Culture Theory: Essays on Mind, Self, and Emotion. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Gritzer G, Arluke A. The Making of Rehabilitation: A Political Economy of Medical Specialization, 1890–1980. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hallowell I. Ojibwa Metaphysics of Being and the Perception of Persons. In: Hallowell I, editor. Culture and Experience. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Disability in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufert J, Locker D. Rehabilitation Ideology and Respiratory Support Technology. Social Science & Medicine. 1990;30(8):867–877. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90214-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H, Cohern H, Blazer D, Meador K, Westlund R. A Brief Depression Scale for Use in the Medically Ill. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1992;22(2):183–195. doi: 10.2190/M1F5-F40P-C4KD-YPA3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky M. Alchemists’ Visions: Cultural Norms In Eliciting and Analyzing Life History Narratives. Journal of Aging Studies. 1990;41:17–29. doi: 10.1016/0890-4065(90)90017-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky M. Sociocultural Factors Shaping Adaptive Technology Usage: Fulfilling the Promise. Technology and Disability. 1993;21:71–78. doi: 10.3233/TAD-1993-2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky M, Rubinstein R. Ethnicity and Lifetimes: Self Concepts and Situational Contexts of Ethnic Identity in Late Life. In: Gelfand D, Barresi C, editors. Ethnic Dimensions of Aging. New York: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky M, Rubinstein R. Ethnic Differences In Elderly Widowers’ Reactions To Bereavement. In: Sokolovsky J, editor. Aging, Culture, Society. Brooklyn: Bergin & Garvey; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky M, Sankar A. Extending the Critical Gerontology Perspective: Cultural Dimensions. The Gerontologist. 1993;33(4):355–362. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.4.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy R. The Body Silent. New York: Henry Holt and Company; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy R, Scheer J, Murphy Y, Mack R. Physical Disability and Social Liminality: A Study in the Rituals of Adversity. Social Science & Medicine. 1988;26(2):235–242. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90244-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. NIH Publication No 93–3509. 1993. Research Plan for the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research. [Google Scholar]

- Neugarten B, Hagestad G. Age and the Life Course. In: Binstock R, Shanas E, editors. Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ortner S. Anthropological Theory Since the Sixties. Comparative Studies in Society and History. 1984;26(1):126–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp S, Vrana S. Substituting Nonsomatic for Somatic Symptoms in the Diagnosis of Depression in Elderly Male Medical Patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;146(9):1197–1200. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.9.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer J, Luborsky M. The Cultural Context of Polio Biographies. Orthopedics. 1991;14(11):1173–1184. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19911101-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiebe K. Memory, Identity, History and the Understanding of Dementia. In: Thomas L, editor. Research on Adulthood and Aging: The Human Science Approach. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer M, Troll L. Expected Life History. American Behavioral Scientist. 1985;29(6):746–764. [Google Scholar]

- Shweder R. Thinking Through Cultures. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Shweder R, Bourne E. Does the Concept of the Person Vary Cross-Culturally? In: Shweder R, LeVine R, editors. Culture Theory: Essays on Mind, Self, and Emotion. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Stein H. Rehabilitation and Chronic Illness in American Culture. Ethos. 1979;71:153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Stein H. American Medicine as Culture. New York: Westview; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J, Fagerhaugh S, Glaser B, Maines D, Suczek R, Weiner C. Chronic Illness and the Quality of Life. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Stouffer SA. American Soldier. 1 & 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. Disability Transitions for Older Persons with Arthritis. Journal of Aging and Health. 1992;4(2):2l2–243. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L, Jette A. The Disablement Process. Social Science & Medicine. 1993;38(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White G, Kirkpatrick J, editors. Person, Self, and Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wright . Physical Disability: A Psychosocial Approach. New York: Harper & Row; 1983 [1960]. [Google Scholar]

- Wood P. International Classification of Impairments. Geneva: WHO; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Zola I. Missing Pieces: Chronical of Living with a Disability. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]