Abstract

The Moving to Opportunity (MTO) housing experiment has proven to be an important intervention not just in the lives of the poor, but in social science theories of neighborhood effects. Competing causal claims have been the subject of considerable disagreement, culminating in the debate between Clampet-Lundquist and Massey (2008) and Ludwig et al. (2008). This paper assesses the debate by clarifying analytically distinct questions posed by neighborhood-level theories, reconceptualizing selection bias as a fundamental social process worthy of study in its own right rather than as a statistical nuisance, and reconsidering the scientific method of experimentation, and hence causality, in the social world of the city. I also analyze MTO and independent survey data from Chicago to examine trajectories of residential attainment. Although MTO provides crucial leverage for estimating neighborhood effects on individuals, as proponents rightly claim, I demonstrate the implications imposed by a stratified urban structure and how MTO simultaneously provides a new window on the social reproduction of concentrated inequality.

Contemporary wisdom traces the idea of neighborhood effects to William Julius Wilson’s justly lauded book, The Truly Disadvantaged (1987). Since its publication a veritable explosion of work has emerged, much of it attempting to test the hypothesis that living in a neighborhood of concentrated poverty has pernicious effects on a wide range of individual outcomes—economic self-sufficiency, violence, drug use, low birth weight, and cognitive ability, to name but a few.2

There is, however, an earlier neighborhood-effects tradition that charted a different course (Sampson and Morenoff 1997; Wilson 1987:165–166). Although not opposing the prediction of individual outcomes, urban sociologists of the classical Chicago School were instead fixated on the structural consequences of urbanization for the differential social organization of the city, especially its neighborhoods. Prominent questions included how the culture and structure of a community, such as its capacity for social control or the age-graded transmission of social norms, were influenced by economic segregation and ethnic heterogeneity, and how this process shaped delinquency rates (Park and Burgess 1925; Shaw and McKay 1942). The unit of analysis was thus not the individual but rates of social behavior that varied by neighborhood-level cultural and social structure.3 The theoretically implied unit of intervention was the community itself. To this day, even though little heralded, interventions such as the Chicago Area Project survive.4

Broadly stated, then, two distinct approaches to neighborhood effects have been put forth and in different intellectual eras one or the other has dominated. Each approach is important to the advancement of scientific knowledge and the design of social policy. Yet there can be little doubt which one dominates current social inquiry, especially in the policy world. The question of the day has turned ever more sharply to one slice of the pie—in essence the phrase “neighborhood effects” has come to stand for effects on individual differences. Moreover, the specter of “selection bias” has been raised to cast doubt on almost all observational research, a nuisance to be extinguished with what is widely claimed as the most scientific of all methods, the experiment.

Enter the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) experiment. Bursting on the scene with a splash and following the path of contemporary wisdom, MTO has been framed as a test of Wilson’s The Truly Disadvantaged (Ludwig et al. 2008). MTO publications and presentations appear to have cast doubt on the general thesis that neighborhoods matter in the lives of poor individuals. At least that is the message many, including myself, have heard up to now.5 With the weight of the experimental method behind them, broad assertions have also been made about the best way to conduct research, the validity of theories of neighborhood effects writ large, and the direction that policy should take. For example, because MTO “used randomization to solve the selection problem,” it has been said to offer “the clearest answer so far to the threshold question of whether important neighborhood effects exist” (Kling, Liebman and Katz 2007:109; see also Oakes 2004). Considering that over a century of neighborhood ecological research forms the baseline, this is high praise for one study. Or consider the headline: “Improved Neighborhoods Don’t Raise Academic Achievement” from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER 2006). That may well be true, but one wonders how such a strong inference could be drawn from a study that randomized housing vouchers to individual families rather than improving neighborhoods. Put differently, MTO is not a neighborhood-level intervention. To top things off, Clampet-Lundquist and Massey (2008) charge that small differences in neighborhood racial integration induced by MTO’s random allocation of housing vouchers do not offer a robust test of neighborhood effects.

It is no wonder that scholars have been puzzled and that controversy has grown. Despite MTO’s strengths in the experimental end of social inquiry, disagreement reigns on how to analyze and generalize from a housing-voucher study designed to assess individual outcomes among the extreme poor to all of neighborhood-level theory. What constitutes the proper interpretation and statistical analysis of MTO, and what effect is being estimated? To what populations and levels of analysis can we infer neighborhood treatment effects? What does the treatment capture and was it sufficient? What theory does MTO test? Perhaps more fundamentally, what is a neighborhood effect? It could hardly come as better timing for the American Journal of Sociology to provide the intellectual context for thinking seriously about these questions, for the questions are not only foundational but the answers are likely to reverberate widely in the social sciences. The motivation for renewed reflection stems from a paper that questions and then reanalyzes the causal treatment in MTO (Clampet-Lundquist and Massey 2008), paired with a response that defends MTO and its mandate (Ludwig et al. 2008). The good news is that these dual scholarly interventions move the field forward by providing new analyses, new insights, needed clarifications, and most importantly, an opportunity to reconsider the very idea of neighborhood effects. The papers in question are also exceptionally clear and collegial, models of scholarship as it should be.

Although I applaud the authors and find much to agree with in both papers, a dispute nonetheless remains. The crucial disagreement in the debate turns on the proper analytic approach to neighborhood selection in an experimental design and the strength of the MTO treatment itself. It is to these two issues that I focus most of my attention. To enrich the debate I present a targeted set of new analyses of MTO data along with original data from a longitudinal observational study that complements in time and space one of the MTO sites, allowing direct comparison of patterns of residential movement. My thesis grants validity to each paper, accepting key conclusions of Ludwig et al. (2008) while highlighting, in a way that supports Clampet-Lundquist and Massey (hereafter CM), the nature of causality in a socially segregated and stratified world. I also argue for alternative ways to conceive of neighborhood effects, selection bias, and at bottom the social structure of inequality. Ironically, the individualistic intervention of MTO turns out to provide an intriguing alternative vehicle for observing the reproduction of inequality.6

MTO BASICS

I paint the picture of baseline facts with a broad brush because lucid accounts have filled in the details elsewhere, including not just the two papers in question but prior reviews.7 The design of MTO is relatively straightforward. Families below the poverty line and living in concentrated poverty (40% or greater) in five cities in the mid 1990s were made eligible to apply for housing vouchers. Those that did were randomly assigned to one of three groups: experimental, Section 8, and controls. The experimental group was offered a limited-term housing voucher that, if used, had to be applied toward residence in a neighborhood with less than 10% poverty. Counseling and assistance in housing relocation were also provided. Those in the Section 8 group were offered vouchers but with no restrictions imposed on where they could move. The controls experienced no treatment. The baseline population eligible for the voucher study was not only poor but predominantly black or Latino and comprised mainly of female-headed families on welfare and living in concentrated public housing circa 1995–1997—or in what many would term the “ghetto.”

A slightly overly simplified typology suggests that five main outcomes have been studied: adult economic self-sufficiency, mental health, physical health, education, and risky behavior. No significant differences between treatment and controls have been reported by MTO researchers for adult economic self sufficiency or physical health, the former of which is challenged by CM. Significant positive effects of the MTO intervention have been reported for adult mental health, young female education, physical and mental health of female adolescents, and risky behavior (e.g., crime, delinquency) among young girls. Long-term adverse effects of moving are found for the physical health and delinquency of adolescent males in the MTO sample.8 And null effects have been reported for a number of outcomes, such as cognitive achievement. Complexities in the interpretation of MTO thus extend beyond the critique by Clampet-Lundquist and Massey (2008).

It seems reasonable to conclude from all this that the MTO results are mixed rather than negative—conditional on outcome and subgroup. That is to say, sometimes neighborhood effects matter, sometimes they do not. This state of affairs hardly seems surprising. It would be astonishing after all, suspicious even, if neighborhood effects were found across the board for all outcomes, all measures. Nothing in social science is that robust, and no theory of which I am aware posits ubiquitous or large neighborhood effects on everything. Besides, it is a mistake to equate small effect sizes with unimportance, especially if obtained under unusual circumstances as seems to the case here (Prentice and Miller 1992). Moreover, some of the effects reported, such as on adult mental health and female adolescent behavior, are rather large in magnitude. Because depression is implicated in many life-course sequelae (Langer and Michael 1963), experimentally induced neighborhood effects in the mental health domain are especially notable.9

So why the disproportionate emphasis, especially in public pronouncements, on the idea that MTO has disproven neighborhood effects? This is a good question and I suspect one answer is simply that debunking is both tempting and important. Problems set in when debunking is combined or set up with a disciplinary straw man. Over time, however, the complexities have become more apparent and by now, all sides have moderated and seem to be declaring a truce of sorts. Ludwig et al. themselves argue that it is unfortunate that MTO has been interpreted in “overly negative” terms (2008: 17), and I find their summary of MTO evidence exceedingly fair.

The time therefore appears ripe for an interdisciplinary assessment of what we might term the “Neighborhood Question, Experimental Style.” I take a broad evaluative stance, one compelled by the reach of Ludwig et al.’s paper and reflected in its title: “What Can We Learn about Neighborhood Effects from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment?”

LEVELS AND SCOPE OF INFERENCE

In the counterfactual paradigm advocated by Ludwig et al., the general question is whether the same individual, residing in a poor neighborhood, would follow a different course if he or she in fact resided in a non-poor neighborhood. Individuals are the unit of analysis and selection bias is the main concern. Randomly assigning individuals to neighborhood treatment is the scientifically proposed way to equate otherwise dissimilar people, thereby permitting estimation of an average causal effect. Of course, MTO did not (and could not) assign persons where to live. Housing vouchers were randomly assigned and individuals were induced to move.

A separate question asks how to explain variations in rates of behavior or events across neighborhoods. Here the counterfactual is not about individuals but neighborhoods, leading to experiments (even if only thought experiments) where neighborhoods are randomly allocated to treatment and control conditions and a macro-level intervention introduced. Ludwig et al. (2008: 42) properly caution readers not to draw inferences from MTO about neighborhood interventions, but many readers seem not to have listened. I would go further and argue that the community level causal question is not only an interesting and compelling one, but equal in intellectual integrity to the individual one. By this logic it follows that research needs to take seriously the measurement and analysis of neighborhoods as important units of analysis in their own right, especially with regard to social and institutional processes (Raudenbush and Sampson 1999).

It is important to emphasize that a theory aiming to explain concurrent neighborhood-level variability is logically not the same enterprise as explaining how neighborhoods exert long-term effects on individual development (Wikström and Sampson 2003). For example, we may have a theory of social control that accurately explains variation in crime event rates across neighborhoods regardless of who commits the acts (residents or otherwise), and another that accurately explains how neighborhoods influence the individual behavior of their residents no matter where they are. In the latter case neighborhoods have developmental or enduring effects, in the former situational effects.10 One is not mutually exclusive of the other. The logical separation of explanation is reinforced by considering routine activity patterns in contemporary cities, where residents typically traverse the boundaries of multiple neighborhoods during the course of a day.

In short, if we want to learn about the causal effects of neighborhood interventions in an experimental design, the proper method is to randomly assign interventions at the level of neighborhoods or other ecological units, not individuals. Examples include the random assignment of neighborhoods to receive a network-based AIDS intervention, community policing, or an effort to mobilize collective efficacy (e.g., Sikkema et al. 2000). If rates of sexually transmitted diseases or public violence were significantly reduced after the randomized interventions, or if dissimilar outcomes in particular were affected (e.g., civic trust; social interactions), we may then speak of an emergent neighborhood-level effect. From a public policy perspective, neighborhood or population-level interventions may be more cost effective than those targeted to individuals.11

Neighborhood Effects for Whom? On What?

The MTO is restricted to a narrow slice of the population. Those eligible to participate in MTO included poor families with children living in public housing and in neighborhoods with over 40 percent in poverty. In cities like Chicago this meant virtually all black (98%), female-headed (96%), non married (93%) and extremely poor households, with mean total income less than $8,000 (Orr et al. 2003: Appendix C2). To get an idea how small a slice this restriction reflects, I calculated the fall off from a representative sample after applying an MTO “adjustment” to the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN). Described more below, the PHDCN selected over 4,500 families with children under 18 at almost the exact same time as the MTO did in Chicago—1995. The sample was designed to be representative of the population of children growing up in Chicago at the time. At baseline there was not a good measure of living in public housing so I selected those families headed by a black, non-married female, receiving welfare and living in a neighborhood with greater than 40% poverty. Based on published MTO data this selection characterizes the MTO Chicago site—if anything it is probably a generous definition as it includes some non-public housing families. Out of approximately 4600 families, 139 fit the MTO bill. When weighted to account for the stratified sampling scheme, 5% of the PHDCN population is MTO equivalent. These MTO “equivalents” establish how far into the extreme tail of the poverty and race distributions the MTO study reaches: 5% of the population does not a general test of neighborhood effects make.

It is likewise important to appreciate the implications of the fact that at baseline MTO adults and their children had for the most part grown up in high poverty neighborhoods, raising a developmental question about life-course timing and the durability of neighborhood effects. If the effect of disadvantage is cumulative, lagged, or most salient early in life, as recent evidence suggests for cognitive ability and adolescent mental health (Sampson, Sharkey and Raudenbush 2008; Wheaton and Clarke 2003), then moving out, while still potentially important, does not bear on perhaps the most critical neighborhood influences in early childhood. In this sense, the MTO experiment may be inconsistent with theoretical perspectives that stress early brain development and critical periods where contextual effects get “locked in” (Shonkoff and Phillips 2000, chap. 8). This problem becomes even more complex if we consider that most families living in severely disadvantaged neighborhoods have lived in similar environments for multiple generations (Sharkey 2008), raising the possibility that the influence of disadvantage extends across generations.

The “outcome” question is another issue. Should we expect neighborhood effects on all manner of things? A vast number of individual outcomes have been subjected to the MTO design. In one recent study, there is a web appendix with over 100 pages of outcomes (Sanbonmatsu et al. 2006). Although the detail is impressive at one level, it is theoretically confusing at another. The classical social organizational theories of the Chicago School, and many contemporary revisions, hypothesized specific pathways by which social mechanisms were differentially related to various phenomena, such as delinquency rates (Shaw and McKay 1942) and mental disorders (Faris and Dunham 1939). Social disorganization theory, for example, specifies a hypothesized link running from concentrated disadvantage, instability, and heterogeneity through diminished adult control of peer groups, to gang formation, and eventually to delinquency (Sampson and Morenoff 1997:16–20). It is notable in this light that some of the strongest findings to date on MTO pertain to crime and mental health. But when neighborhood-effects theory is invoked, Ludwig et al. (p. 4) cite Wilson (1987) as one of the “original theories” to claim that neighborhood effects are primarily about poor individuals and economic outcomes—the spatial mismatch hypothesis in particular. Neighborhood effects (and Wilson) are simultaneously broader and more specific than that, and I would not consider spatial job mismatch to be one of the more compelling neighborhood theories.

What is the Social Mechanism and Ultimate Causal Question?

As Ludwig et al. note (p. 9), MTO “bundles” the neighborhood treatment and does not tell us about why neighborhoods matter for individuals, if they do. When MTO families move from one neighborhood to another, entire bundles of variables change at once, making it difficult to disentangle change in neighborhood poverty from simultaneous changes in other structural factors and social processes (Katz, Kling and Liebman 2001:621). Even with a non-bundled treatment, the social mechanisms underlying neighborhood effects in MTO are rendered invisible. This is not a flaw in MTO but rather speaks to the role of experiments in scientific research—experiments do not reveal causal explanation in any direct sense. Nor does any technique, be it matching or instrumental variables. Causal explanation requires theory and concepts that organize knowledge about (typically) unobserved processes or mechanisms that bring about the effect (Heckman 2005).

Further, although moving is a major life event associated with negative outcomes for youth (Hagan, MacMillan and Wheaton 1996; Haynie and South 2005), neighborhood change is coupled with moving by the MTO design. Hence MTO cannot (experimentally) separate the impact of moving itself from differences in neighborhood context. Relatedly, MTO cannot estimate the impact of moving into poverty, or the effect of neighborhood change on stayers.

We can now better appreciate the causal question MTO asks. The study is spot-on for answering the policy question: Does the offer of a housing voucher to move to a nonpoverty neighborhood affect the later outcomes of the extreme poor? One might add: Among those who have grown up in poverty and arguably have already experienced its developmental effects? The MTO question is certainly of substantial interest to policy makers who are considering whether to provide vouchers to induce mobility among the very poor. But should housing policy for a select group of the population be in the driver’s seat when numerous other questions derived from neighborhood-effects theory are at stake? To my mind, the claim that MTO is scientifically superior because it experimentally addresses the “threshold” question of whether neighborhoods matter in the first place is only correct to the extent that (a) we consider the voucher-induced mobility question answered by MTO to be broadly and accurately reflective of neighborhood contextual effects, (b) we stick to individual level inference and set aside neighborhood-level interventions, and (c) we bracket causal theory of the mechanisms that produce neighborhood effects and selection into the treatment—or what Holland (1986) termed the “causes of the effect.”

Selection Bias and MTO

Any discussion of selection into treatment leads inevitably to the undeniable strength of MTO and yet one of the major disagreements in the debate. Set within the inherent limits imposed by the MTO design as summarized so far, the experimental allocation of treatment is a very big deal. I believe the MTO is a major advance to social science and I agree with almost everything Ludwig et al. claim in terms of its ability to solve the selection bias “curse” (p. 7).12 Although an old issue, Jencks and Mayer (1990; Mayer and Jencks 1989) can be considered the foremost source of late 20th century anxiety over neighborhood selection bias. In a widely cited critique, they essentially asked the question: How do we know that the neighborhood differences in any outcome of interest are the result of neighborhood factors rather than the differential selection of adolescents or their families into certain neighborhoods? They concluded that we did not know.

For this reason, it is important to underscore the validity of Ludwig et al.’s claim (p. 7) that selection bias in observational research raises a hornet’s nest of analytic problems which MTO does solve at the individual level of inference and in terms of balancing the data on unobservables (even allowing that a substantial proportion of participants did not take up the offer of a voucher). The randomized design advantage of MTO sets it apart from volumes of research published in our journals that rely on ex post explanations typically derived from regression models that load up on individual-level control variables and that leave undefined the causal counterfactuals under study. In studies of this sort Ludwig et al. worry mainly about omitted variable bias in promoting MTO—their concern is that there is some (undefined, unobserved) quantity out there that we have failed to measure after all these years, or cannot measure. Hence the experiment.

Yet I worry as much if not more about what I will call the included variable bias problem, one that, while more subtle, wreaks just as must havoc with observational research. Consider that many (most?) of the covariates that make their way into typical regression models represent potential causal pathways by which the neighborhood may influence the outcome of interest. For example, in an attempt to account for characteristics of individuals and families that might influence both selection into poor neighborhoods and individual outcomes, observational studies often include control variables such as income, family structure, depression, health problems, criminality, physical disabilities, education, and peer influence. But if one is to interpret resulting estimates as a test of neighborhood effects, one must make the assumption that all controls are pre-treatment covariates—i.e., unaffected by neighborhood. This is an unwarranted assumption given the existence of a long line of research positing neighborhood effects on health, family norms, family structure, adult labor market outcomes, and more (Duncan and Raudenbush 2001).

The larger point is that the common practice of estimating “direct” neighborhood effects using regression-based approaches that control for endogenous covariates has the net result of distorting the multiple pathways by which neighborhoods may influence developmental outcomes, especially among children, and thereby inducing bias.13 The introduction of time-varying covariates makes things even worse, and propensity matching alone is not a sufficient antidote for addressing developmental processes. If observational data are to be used in a dynamic framework, then new approaches are required. Fortunately there are promising methods that can integrate a dynamic life-course framework with neighborhood effects. Before turning to this line of inquiry, however, it is first necessary to assess CM’s claim about the treatment itself: Understanding the nature of the treatment in MTO is directly linked to formulating effective analytic strategies.

SEGREGATION AND NEIGHBORHOOD TREATMENTS

The realized change in neighborhood environments among families receiving vouchers is questioned by CM because the experimental group moved from and to largely segregated black areas subject to the reinforcing disadvantages highlighted in the work of Wilson (1987) and Massey and Denton (1993). The initial experimental-control group differences—even in poverty—diminished over time as families increasingly moved back into neighborhoods similar to those at baseline. Further, children in the MTO experimental group attended schools that differed little from those in the control group in terms of racial composition, average test score performance, and teacher/pupil ratio. In fact, impacts on school environments were “considerably smaller than impacts on neighborhoods” (Sanbonmatsu et al. 2006:649). CM are thus not surprised that moving within segregated neighborhood contexts, even with improvements in economic status, would produce small effects on adult economic sufficiency. In response, Ludwig et al. claim large differences in neighborhood poverty were produced—the intended goal of MTO.

As I read CM, it is not just about racial composition but its entanglement with resource deprivation and disadvantage. They are not equating racial composition with poverty or disadvantage in an essentialist way, in other words; rather, the argument is that social allocation processes in the U.S., with its particular history of race relations, has led to acute sorting along racial-economic cleavages that disadvantage blacks (p. 17). One can imagine, and one can find, other societies where segregation processes that link ascriptive with achieved characteristics are not present or at least not as severe. In order to assess the implications of the race-disadvantage nexus relative to poverty alone, I examine two distinct issues and kinds of data. I first analyze the structure of residential moves of MTO participants across multiple social dimensions and levels of neighborhood, both static and dynamic. Second, I consider the implications of social-ecological confounding for selection bias more generally by analyzing patterns beyond the MTO sample.

MTO Trajectories

I analyze data from the Chicago MTO site because it permits a strategic comparison with the PHDCN study introduced above, one that entails a detailed set of neighborhood-level measures of the city and metropolitan area. This choice simultaneously yields other strategic benefits. Chicago is representative or in the middle of the MTO strength-of-treatment distribution (Ludwig et al., p. 37, Figure 1), ensuring no “stacking of the deck” in favor of either side in the debate. Further, Chicago was the site of much of Wilson’s (1987) work, a key motivator for MTO.

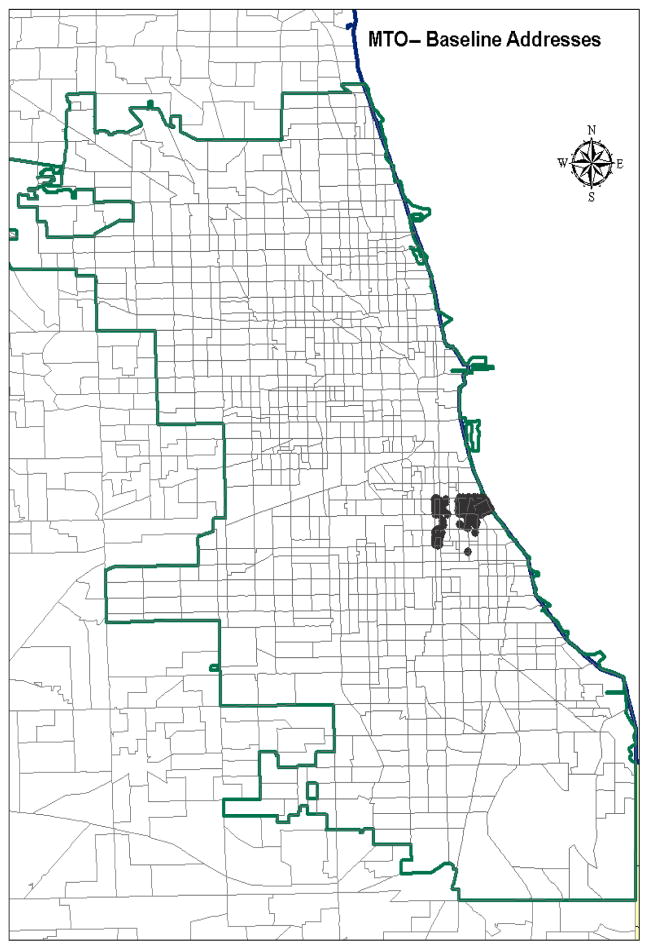

Figure 1.

Clustering of MTO Families at Baseline in Inner City Poverty Areas of Chicago

My goal is to examine neighborhood attainment as the outcome of the treatment, not individual characteristics like crime or economic sufficiency. Following MTO publications, I begin with census tracts as operational units, made possible by linking geocoded address data over time. If the MTO intervention made a fundamental or lasting difference in residential location, the ultimate outcome is where people are living several years out and not just a short time after the experiment when voucher moves were restricted. To test this I examine neighborhoods of residence at the follow-up in 2002, about 6 years after the experiment. It is important to note that the average number of years lived at the destination address was 3.38 years for experimentals and 3.29 for controls (not significantly different), a substantial rather than fleeting amount of time.

I focus mainly on a holistic measure of concentrated disadvantage, drawing on a long line of research demonstrating the clustering of racial and socio-economic segregation across time and multiple levels of ecological analysis (e.g., Land, McCall and Cohen 1990; Massey and Denton 1993; Sampson and Morenoff 1997). Building on this prior work and existing theory, Sampson et al. (2008) recently examined six characteristics of census tracts, taken from the 1990 and 2000 U.S. Census: poverty, unemployment, welfare receipt, female-headed households, racial composition (percentage black), and density of children. For the city of Chicago and the U.S. as a whole (representing over 65,000 census tracts), only one linear factor could be reliably extracted in each decade based on a principal components analysis (see Table 1, Sampson et al., 2008). Consistent with urban theory, CM, and prior research, the data confirm that race, family structure, and resource deprivation are ecologically knotted at the neighborhood level, not just in Chicago but across the U.S. (Massey and Denton 1993). I therefore focus on a summary scale of concentrated disadvantage rather than a single item.14

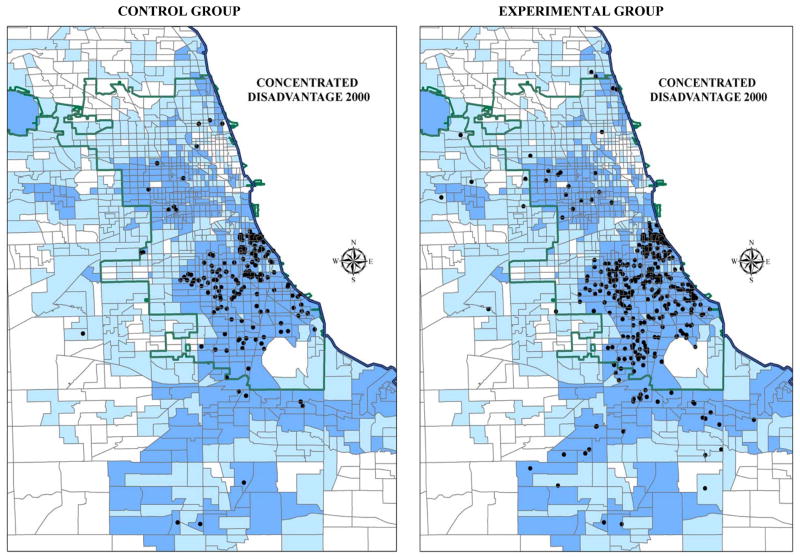

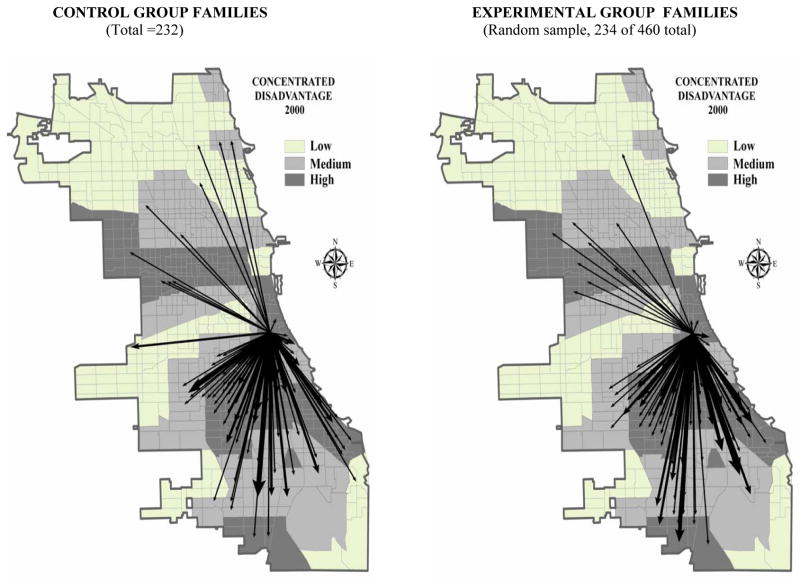

Recall that MTO began with poverty neighborhoods, which in Chicago were clustered in a small number of census tracts on the south side of Chicago in the Grand Boulevard, Douglas, and Oakland communities. Figure 1 shows the tight clustering. Where did the take-up families move? Figure 2 gets to the heart of the debate by depicting the location of participants at the end of the last follow-up, mapped across the Chicagoland area. (There is no treatment difference in staying—92% of both groups remained in the metropolitan area). The two panels plot destination addresses shaded by the summary index of concentrated disadvantage, trichotomized here for parsimony into equal thirds based on the metropolitan distribution. Following Ludwig et al., I focus primarily on comparisons between the control and experimental group rather than the selection decisions among compliers alone. Any differences between groups can thus be attributed purely to the experiment.

Figure 2.

Residential Movement of Chicago MTO Families: Destination Neighborhoods in 2002 by Key Treatment Groups and Concentrated Disadvantage of Census Tract in the Greater Chicago Metropolitan Area

Note: Concentrated disadvantage trichotomized unto equal thirds. Lightest shading indicates “low” and darkest “high” disadvantage.

Figure 2 tells a clear story. MTO movers spread outward from the inner city (cf. Figure 1) but final destinations are highly structured. Entire swaths of Chicago are simply untouched by experimental and control movers alike, as is most of the metro area. Even if we limit the comparison to controls versus self-selected compliers within the treatment group, the same conclusion holds: The vast majority of all MTO participants move close by to other south-side Chicago communities which are in the upper range of concentrated disadvantage. Relatively few moved elsewhere, but when they did the destinations were a systematic cluster of communities on the northwest side and close-in suburbs in the southern part of the metropolitan area, again qualitatively similar in concentrated disadvantage. Although there are considerably more experimental group members and proportionately more of them moved out of the city of Chicago, the observed pattern is striking. The structure of movement appears to be relatively invariant in geographic spread (t-test for distance from origin neighborhoods is not significant) and exposure to entrenched pockets of disadvantage. The modal picture is a dual migration southwards along an upside down “T”—a spatial regime of concentrated disadvantage.

CM appear justified in their concern: MTO induced residential outcomes over the long run that differ in poverty but not necessarily racial integration or the constellation of factors that define the concentration of disadvantage. I would further argue that even for poverty the differences are one of degree, not kind. For destination tracts the experimental reduction was from 42 to 37% below poverty. This five percentage point reduction (or 15%, compliance adjusted) is statistically significant consistent with Ludwig et al. (weighted t-ratio of difference = −2.78), but is the glass half empty or full? Consider that experimentals were still living in neighborhoods that by most definitions are high poverty and within which very few Americans will ever live. Aggregated across all five sites the data also reveal a considerable (> 30% average) poverty rate for both groups (Kling et al. 2007: 88) and a nontrivial 20% poverty rate even for compliers. Segregation was barely nudged—both experimental and controls in Chicago lived at destination in areas that were almost 90% black (n.s.). It is important to note that “scaling up” to account for complier status (see Ludwig et al.) scales up standard errors too and thus does not change the significance of differences. At other sites, average percent minority shares are over 80% for both groups. Linear differences in the principal components scale of concentrated disadvantage, which weights poverty more than race, are significant by treatment group (p < .05). A z-score scale including all U.S. and Chicago area moves is not significantly different. Consistent with Figure 2, I thus conclude that while neighborhood poverty differs, as intended, in the end MTO experimental differences are marginal overall and unfolded within similar structural contexts of concentrated disadvantage.

This conclusion is backed up by consideration of additional evidence for neighborhood characteristics that have so far not been central to the MTO discussion. For tracts in Chicago where police data were available, I examined homicide and burglary rates in 2000–2002. Using a community survey of Chicago from PHDCN in 2001–2002 that closely matches in time the MTO follow-up, I created neighborhood-level measures (see Raudenbush and Sampson 1999) of social cohesion, intergenerational closure, social control, legal cynicism (“anomie”), reciprocated exchange among neighbors, friend/kinship ties, tolerance of deviance, organizational participation, victimization, perceived violence, and disorder. Of these more than a dozen characteristics measured independently from MTO, none were significantly different (p < .05) between the treatment and controls.15 Limiting to Chicago may reduce differences somewhat given that experimentals were more likely to leave the city than controls (17% vs. 12%), but the similarity of neighborhood processes between randomization groups for the vast majority who stayed is evident.

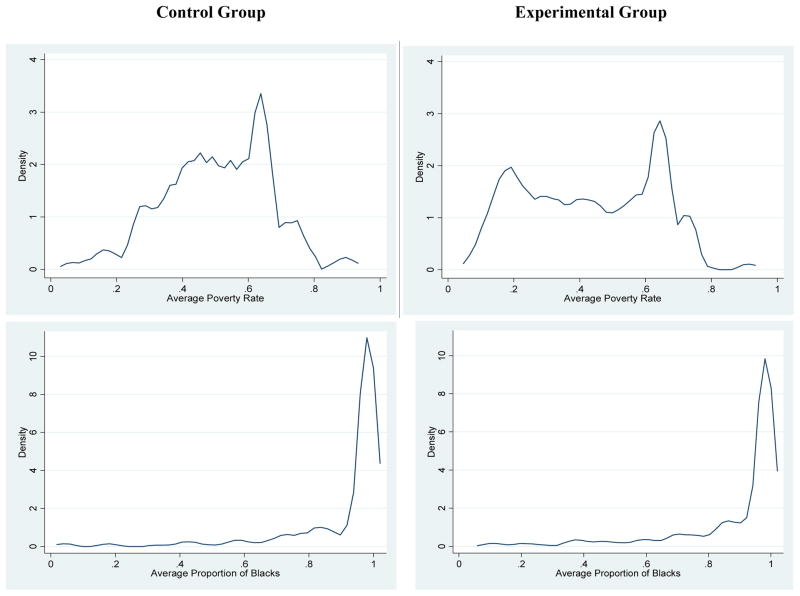

What about interim moves? I have focused on destination neighborhoods for theoretical reasons but consistent with MTO publications I found a significant (p < .01) 9-point difference between the experimental and control group in duration-weighted poverty. However, the duration weighted difference for percent black is only 2 points and not significant (at .05 level), supporting CM. To further examine this issue I follow Kling et al. (2007: 87) by presenting in Figure 3 density kernel estimates of duration-weighted percent black and poverty. In essence a non-parametric smoothed histogram, Figure 3 confirms that when we account for average time spent in each tract, MTO’s modest poverty effect (top panel) was imparted onto a segregated urban structure (bottom panel). The density distribution functions for experimentals and controls are virtually indistinguishable in their shape and clustering in the right hand tail of hyper segregation.

Figure 3.

Duration-Weighted Kernel Density Estimates of Poverty and Percent Black by MTO Treatment Group

Note: All graphs reflect kernel densities based on an Epanechnikov function and a bandwidth of .02. Average poverty rate and average percent black are duration weighted averages at all tract locations since random assignment with census interpolation between 1990 and 2002. Data also randomization weighted.

Contextual Dynamics

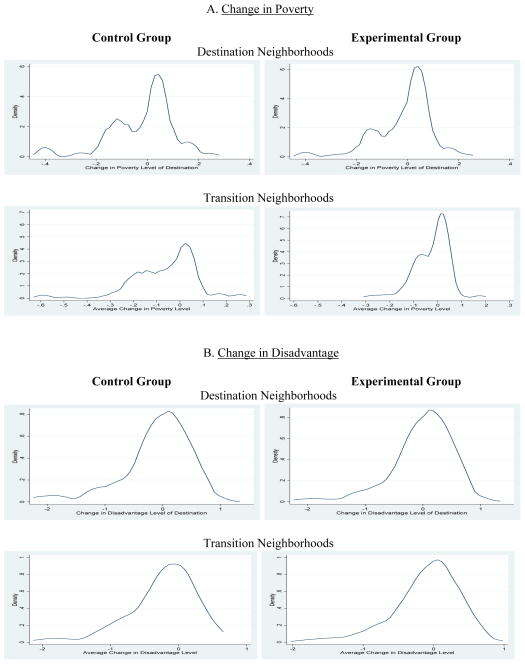

Although neighborhoods are quite durable in their relative positioning over time (Sampson and Morenoff 2006), that does not imply an unchanging treatment. To date, the debate about MTO has proceeded largely as if the neighborhoods to which people move are sequentially static, like a pill. But neighborhoods have trajectories just like individuals. It follows that we need to consider more than just the level (even if interpolated over time) of neighborhood poverty. I might use a voucher to move to a lower poverty neighborhood than a control member, for example, but that neighborhood may be on a downward trajectory (e.g., with declining house values) whereas the control neighborhood is stably poor. The question is whether there are treatment differences in the rate of change and ultimately future viability, of neighborhoods. I therefore examine both raw and residual change in percent poverty, percent black, and concentrated disadvantage from 1990 to 2000 and points in between. Residual change offers us the unique advantage of looking at neighborhood change trajectories after removing the effect of larger metropolitan dynamics.

The dynamic picture tells us a different story than the static. First, there are no significant (p < .05) differences between the treatment and control groups in raw changes in percent black or poverty, nor in residual changes in percent black or poverty. Second, there is a modest difference in changes in concentrated disadvantage, but in a direction that favors controls. On average disadvantage was decreasing over time in Chicago but the rate of decrease was less for the treatment group compared to the controls. This means that when trajectories of neighborhood change are the outcome criterion, the MTO experiment did not result in the treatment group ending up in better off neighborhoods. To better see this, Figure 4 displays density measures for changes in poverty (panel A) and concentrated disadvantage (panel B) in both destination and transition neighborhoods. A close similarity across treatment groups is revealed, especially for disadvantage. I also examined change from 1995 to 2002 in the measures of neighborhood social processes noted above (e.g., cohesion, control): No change trajectory differed significantly by treatment group. These results are consistent with neighborhood employment change (Kling et al. 2007: Web Appendix, Table F14), further confirming a lack of MTO effect on contextual dynamics.

Figure 4.

Change in Poverty and Disadvantage of Destination Neighborhoods and Transition Neighborhoods in Between (Duration Weighted) by MTO Control and Experimental Group

Note: Kernel density, Epanechnikov function, Bandwidth =0.02. Data are randomization weighted.

SPATIAL DISADVANTAGE

Although the unit of ecological analysis is not one highlighted by either CM or Ludwig et al., the spatial proximity of disadvantage nonetheless bears directly on the debate. A number of social analysts have noted that African Americans face a unique risk of ecological proximity to disadvantage that goes well beyond local neighborhoods, including blacks in the middle class. This point is vividly made in Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril Among the Black Middle Class (Pattillo 1999) and highlighted in work showing the spatial disadvantages of black middle-class (and working-class) neighborhoods compared to internally similar white areas (Sampson, Morenoff and Earls 1999). The implication is straightforward: while the black poor might be able to move to a better off census tract with an MTO voucher, that tract is still likely to be embedded in a larger area of poverty and therefore spatial disadvantage. Moreover, prior research has shown evidence consistent with spillover effects or spatial contagion at lower units of analysis. Tracts are not only relatively small in size, they are governmentally defined with ecological borders many have criticized as artificial and highly permeable (for more discussion, see Hipp 2007).

It follows theoretically that we need to consider more than just census tracts in any adjudication of MTO. I do so by taking advantage of the fact that, in Chicago, as elsewhere, local community areas exist that have well-known names and fairly distinctive borders such as freeways, parks, and major streets—especially compared to census tracts. Chicago has 77 such areas averaging about 37,000 persons that were defined many years ago to correspond to socially meaningful and natural geographic boundaries. Although some of these names and perhaps even boundaries have undergone change over time, Chicago’s community areas are still widely recognized by administrative agencies, local institutions concerned with service delivery, and residents alike. They also have distinct names that are widely used (e.g., Hyde Park, Grand Boulevard, South Shore, and Lincoln Park). Community area boundaries have political force and symbolic value that continues (Suttles 1990). It is relevant to remember as well that Wilson’s (1987) thesis of concentration effects was developed using community areas in Chicago as the empirical unit of referent (e.g., see his seminal Chapter 2). I therefore recalibrated the movement in MTO by characteristics of community areas, relying on the finding that the vast majority of moves of both experimental and control groups are clustered within Chicago (see also Figure 2).

Figure 5 displays the spatial network of connections outward from the MTO baseline per Figure 1. As before I seek the big picture on differences in outcome, in this case community-level concentrated disadvantage split into equal thirds (low, medium, and high) based on the Chicago distribution. What we see again, although in a new light, is a striking social reproduction of disadvantage among MTO participants, experimental and control members alike.16 The pattern of neighborhood attainment flows is indistinguishable, suggesting a profound structural constraint.

Figure 5.

Trajectory Flows from Baseline Poverty Neighborhoods by Concentrated Disadvantage in 2000 of Chicago Community Areas. Calculated From Origin-to-Destination Tracts circa 1995–2002 by Control Group and Random Sample of Experimentals

Note: Concentrated disadvantage trichotomized unto equal thirds. Lightest shading indicates “low” and darkest “high” disadvantage. Origin or baseline neighborhoods are collapsed into one “dot.” Arrows reflecting ties between tracts are proportional to volume of movement. Within neighborhood circulation flows and moves between origin neighborhoods not shown.

A non-parametric way to further assess this idea is to calculate the number of families each Chicago community area “received” from the experimental and controls, and then calculate the Spearman’s rank-order correlation. The resulting rank order correlation is .79 (p < .01). Hence when we direct our attention to the pure experimental comparison induced by MTO, we find that both groups not only end up in very similar disadvantaged communities, they move to largely the same exact communities. At some point, then, when we consider the broader notion of spatial disadvantage and see locations converging, individual neighborhood measures become less relevant.17 Clustering is surprisingly present even at the tract level for both groups. Over half (55%) of the experimentals ended up in just 4% of all possible tracts in the Chicago metropolitan area, while 55% of the control group ended up in 3% of all tracts. This analytic approach reveals the limits of focusing on just treatment-induced differences and not examining the sorting of MTO participants to all potential outcomes in the ecological network sense. In network terms, the strong spatial concentration indicates the centrality of a relatively small core of neighborhoods that receives the majority of MTO families, regardless of treatment or complier status. Hence one way to think about things is that there is a community vacancy-like chain to the movement of the poor.

The data to this point show that sorting in MTO is highly structured ecologically. Poor people moved to inequality, with opportunities embedded in a rigid and likely reinforcing dynamic of metropolitan social structure. The replicating nature of moving decisions in MTO prompt a reconsideration of the typical ways of viewing selection bias and complicance in the experiment.

NEIGHBORHOOD SORTING AS A SOCIAL PROCESS

“It is often remarked how difficult it is to get a family to consent to move out of the slum no matter how advantageous the move may seem from the material point of view, and how much more difficult it is to keep them from moving back into the slum.”

Henry Zorbaugh, The Gold Coast and the Slum (1929: 135).

Humans are agents with the decision-making power to accept or reject treatments (Heckman and Smith 1995). Statistics on the “take-up” rate show that a majority of MTO families who were offered a voucher did not actually use it. Families who did use the voucher experienced less neighborhood poverty compared to the noncompliers but the vast majority remained within a relatively short distance from their origin neighborhood. Moreover, many families moved back into poor neighborhoods that were very similar to the ones in which they started, surprising many observers. Yet no one should be surprised at these facts. Back in the 1920s, Zorbaugh (1929) noted the “pull” of the slum and how the strong nature of its social ties kept people returning. It is only from a middle-class point of view, or what Zorbaugh called the “budget minded social agency” (1929:134) that the behavior of those who have grown up in poverty seem “incalculable.”

CM argue that this self-selection, particularly within the treatment group, poses problems for valid causal inference. For one, the “intent to treat” effect will significantly under-estimate the “treatment effect on the treated” or the effect of actually moving. To cope with this challenge, Ludwig et al propose the randomization of being offered a voucher as an instrumental variable to identify the impact of actually using the voucher. Valid causal inference depends on the exclusion restriction that the offer of a voucher will affect outcomes only if participants use the voucher. This seems plausible in MTO, supporting the validity of inferences about the treatment effect on the treated (or “compliers”)—those who would use the voucher if assigned to the experimental condition but who would not use the voucher if assigned to the control group. By weighting according to proportion compliers, Ludwig et al. argue that the unbiased effect of the bundled MTO treatment (combining moving with neighborhood context) can still be estimated, and they show us how in a cogent manner that I expect will continue to be used in future analyses of MTO.

CM further argue that the more time one spends in poverty the greater the neighborhood effect is likely to be, which leads them to conduct an analysis of time spent in poverty, controlling for treatment group status and background factors. In other words, CM perform an analysis that relies on the observational component of MTO data and a regression analysis design. Ludwig critique their method on the grounds that it introduces hidden (or perhaps better put, unknown) selection bias. Their solution is to use the randomization of vouchers as the instrument (interacted with site) this time for the duration-weighted poverty rate, a technique they again cogently explain. Ludwig et al. also argue that those randomized at a later date in the initial baseline period are by definition subject to a different window of exposure. Accounting for these cohort differences and capitalizing on the random assignment, overall Ludwig et al. find no treatment effects of duration in poverty on adult economic sufficiency. They correctly note that in this sort of estimation, the results cannot literally be interpreted as the effects of neighborhood poverty on outcomes but rather the bundle of factors associated with poverty. The multiple characteristics correlated with poverty, such as percent black, could not be simultaneously instrumented due to lack of statistical precision.

My take here is mixed. First, I think CM have done the field a service by emphasizing the importance of cumulative exposure and the need to model the duration of time spent in poverty. Yet the assumptions needed to support their regression framework can and have been properly criticized: While the basic idea of CM may be theoretically justified, the baseline variables available in MTO and its limited developmental or time-varying measures mean that selection bias is still potentially a problem, as CM themselves note (p. 35). Thus, in principle I find the Ludwig et al. argument correct that “instrumenting” is the preferred way to go, especially given the availability of a randomized voucher. I also agree that cohort differences in randomization should be adjusted because they reflect differences in experienced time in poverty.

Second, however, the instrumental variable (IV) method is imperfect—not only because duration in poverty cannot be isolated as the cause, but because of (a) potentially unwarranted assumptions one must make about social interactions18 and (b) moving itself is part of the causal pathway: the MTO design was not set up to experimentally estimate the separate effects of moving and change in poverty. The latter point is particularly relevant given evidence that moving is a major life event that predicts later behavior (Hagan, MacMillan and Wheaton 1996). There may also be mobility-by-neighborhood interactions, perhaps explaining the gender differentials (e.g., over time boys might be more vulnerable to breaking off prior networks or being the new kid in the neighborhood). For this reason, CM are not unwise to want to separate moving or compliance status from the effect of poverty, which their models implicitly try to do. Kling et al (2007: 98–99) recognized this point and entered complier status as a control variable in an IV regression analyses.

In short, CM are right to want to learn about selection and not just dismiss it as noise as do most experimentalists. In a welcome move, Ludwig et al. (p. 36) signal openness to a better understanding of selection. A renewed appreciation of selection processes is thus in order.

Turning Selection Around: The Causes of Effects

Relying on randomization as valorized by the experimental paradigm, even if logistically possible as in MTO, brackets knowledge of how causal mechanisms are constituted in a social world defined by the interplay of structure and purposeful choice. Yet most non-experimental research on neighborhood effects is just as guilty of failing to confront directly and achieve a basic understanding of the social processes that select individuals into neighborhood “treatments” of interest (see also Heckman (2005). Although not articulated in quite this way, the MTO debate suggests that the goal of studying sorting and selection into neighborhoods of varying types is an essential ingredient in the larger theoretical project of understanding neighborhood effects.

Patrick Sharkey and I recently pursued such an agenda and in addition focused on the social consequences of residential selection (Sampson and Sharkey 2008). Our question became how individual mobility decisions combined to create spatial flows that define the ecological structure of inequality, an example of what Coleman (1990:10) more broadly argued is a major under-analyzed phenomenon—micro-to- macro relations. Analyzing longitudinal trajectories of Chicago residents (again using PHDCN) no matter where they moved in the US, our results suggest several implications for understanding neighborhood change and thereby neighborhood effects.

First, a number of previously unobserved factors that represent hypothesized sources of selection bias in studies of neighborhood effects were, despite the litany of suspicions raised in the MTO literature, of surprisingly minimal importance in actual or revealed neighborhood selection decisions. Residential stratification falls powerfully along race/ethnic lines and socio-economic position, especially income and education. These are for the most part the only surviving factors that explain a significant proportion of variance in neighborhood attainment. Even after introducing a variety of theoretically motivated covariates that captured largely unstudied aspects of locational attainment—such as depression, criminality, and social support—the substantive picture of our results was unchanged. It follows that longitudinal studies accounting for neighborhood selection decisions and a fairly simple yet rigorous set of individual and family stratification measures may make for a reasonable test of neighborhood influences.19

Second, whites and Latinos living in neighborhoods with growing populations of nonwhites were more likely to exit Chicago, providing evidence that realized mobility arises, at least in part, as a response to structural changes in the racial mix of the origin neighborhood. The same is not true of black families—the data suggested that it is not African-Americans’ preference for same-race neighbors that seems to matter as much as whites’ and Latinos’ eagerness to exit neighborhoods with growing populations of blacks. Ironically, then, neighborhood conditions appear to matter a great deal for influencing neighborhood selection decisions, suggesting a different kind of neighborhood effect—sorting as a social process.

MTO might be seen by CM as a failure in terms of treatment strength, but if there is any failure, these results suggest it is one of society. Indeed, no matter where individuals choose to live, and no matter what their background or reasons behind their decisions, the racial income hierarchy of neighborhoods is rendered durable (Sampson and Sharkey 2008). The flow analyses in Figures 2 and 5 suggest that MTO moves are no different. Hence while CM’s methods may be limited, a deeper point emerges: In examining the sources and social consequences of residential sorting we need to conceptualize neighborhood selection not merely as an individual-level confounder or as a “nuisance” that arises independent of social context (see also Bruch and Mare 2006; Heckman 2005). Instead, neighborhood selection is part of a process of stratification that situates individual decisions within an ordered, yet constantly changing, residential landscape.

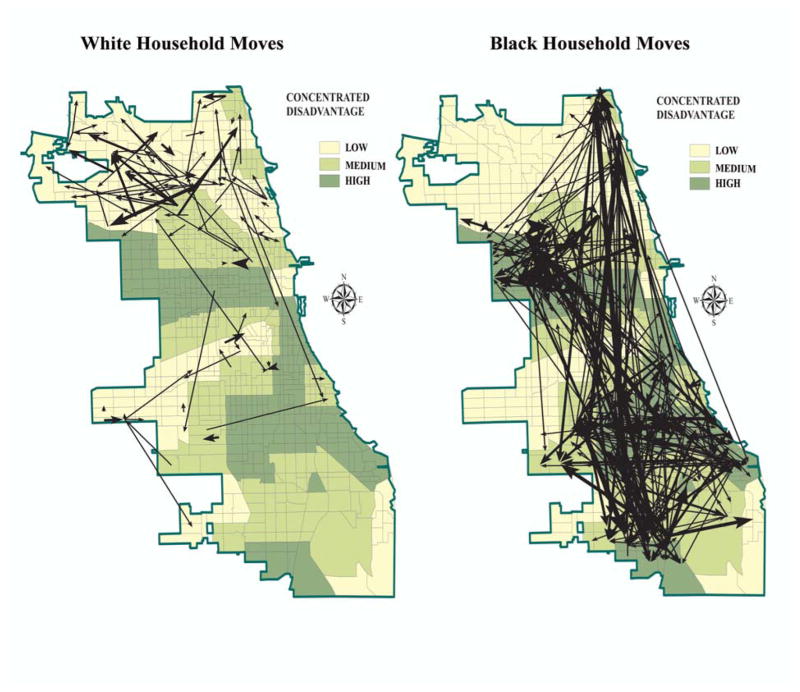

To demonstrate this idea further, Figure 6 displays the moves of black and white families in the PHDCN during the period of the MTO study. These families all have children under 18 like MTO but were not selected on poverty status. For parsimony I present just the moves of black and white families. Ties between census tracts are valued in proportion to volume and again the shading is by community-area concentrated disadvantage. Despite the different sample sizes, whites and blacks form dynamic connections among neighborhoods within what appear to be different parallel universes: There is almost no racial exchange across areas and black families move within sections of the city that are highly circumscribed by concentrated disadvantage.

Figure 6.

Separate Social Worlds of Children’s Exposure to Concentrated Disadvantage: Trajectories of Movement among Representative Sample of Black and White Families in the PHDCN Longitudinal Cohort Study, circa 1995–2002, by Community Area Disadvantage

Note: Concentrated disadvantage trichotomized unto equal thirds. Lightest shading indicates “low” and darkest “high” disadvantage. Ties (arrows) are valued and proportional to volume.

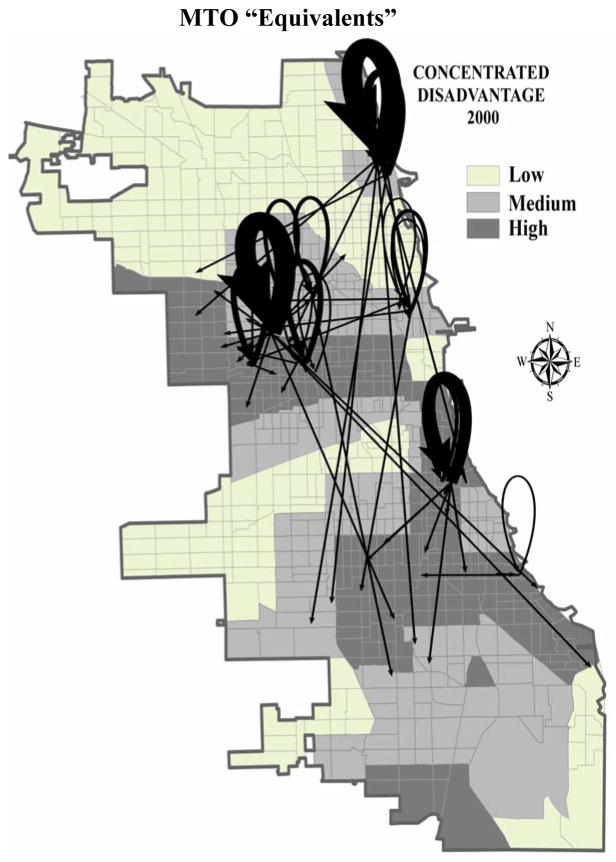

Figure 7 repeats the analysis on MTO “equivalents” and by showing “churning” flows within neighborhoods. The origin community of MTO is captured by PHDCN on the near South Side. We see considerable circulation within that poor sector and moves further south to other disadvantaged neighborhoods, a pattern similar to the MTO flows. A west side cluster and a far north side cluster are also observed. In general, then, the hierarchy of places is rendered durable in both studies. Chicago is only one city, of course, and its take up rate was lowest among MTO sites, but I would hypothesize similar patterns elsewhere. At the national level, Sharkey (2008) has shown the intergenerational transmission of concentrated disadvantage, further demonstrating the durable lock that segregation by race and class has on trajectories of neighborhood attainment.

Figure 7.

Neighborhood Circulation Flows of “MTO Equivalent” Households in the PHDCN Longitudinal Cohort Study (N=139), circa 1995–2002, by Concentrated Disadvantage in Chicago Community Areas. Mobility Ties Between Census Tracts Proportional to Volume and “Loop” Arrows Depict Internal Moves within the Baseline Neighborhoods of Origin

Note: Concentrated disadvantage trichotomized unto equal thirds. Lightest shading indicates “low” and darkest “high” disadvantage.

DEVELOPMENTAL NEIGHBORHOOD EFFECTS

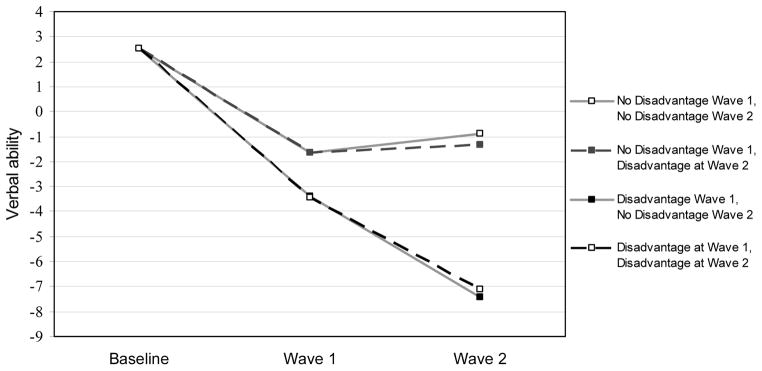

My final set of analyses returns to the idea that neighborhoods have the potential to alter developmental trajectories but that their influence may be set at critical junctures. To illustrate this process, I consider the lagged effect of concentrated disadvantage on trajectories of verbal ability Sampson et al. (2008). The implications for MTO are twofold, bearing on relevant counterfactuals for the effects of concentrated disadvantage and developmental-neighborhood interactions.

Consider first the analytic implications of the clustering of disadvantage for attempts to estimate neighborhood effects at the individual level. When concentrated disadvantage was defined by Sampson et al. (2008) as falling in the upper quartile of the scale distribution (i.e. high disadvantage) across all Chicago census tracts (the origin of the PHDCN sample), the startling result was that no whites and only a few Latinos lived in disadvantaged neighborhoods across three separate time points, making it impossible to reliably estimate treatment effects of disadvantage for these groups. When treatment was defined using the top quartile of the national distribution of concentrated disadvantage, a different problem occurred: virtually all blacks (97 percent) were exposed. When the treatment was instead defined as living in a neighborhood with more than 30 percent poverty, at most 5 percent of whites were exposed at any given time.

The difference between exposure to neighborhood poverty versus the more comprehensive measure of concentrated disadvantage is dictated by the nature of ecological confounding. Conditional on being exposed to high-poverty (> 30%) neighborhoods at baseline, black children were still much more likely to live in segregated areas characterized by welfare dependency, unemployment, and female-headed households. For example, the unemployment rate is over 50% greater in poor areas where blacks live compared to whites, and there is a qualitatively different racial composition as well—3/4th black versus less than a 1/3rd. The stratification of America’s urban landscape by race and class once again reveals that concentrated disadvantage is a different treatment than simple poverty and one experienced almost solely by Chicago’s black population.

The second implication concerns lagged effects and developmental interaction. Building on Sampson and Sharkey’s (2008) study of selection into and out of neighborhoods, PHDCN data were used to formulate a cross-classified multi-level model designed to estimate the effects of concentrated disadvantage on verbal ability, a case where the contextual treatment, outcome, and confounders all potentially vary over time (Hong and Raudenbush 2008; Robins 1999; Robins, Hernan and Brumback 2000). Information gleaned from analysis of residential selection though time was used to weight each person-period observation by the inverse probability of receiving the treatment (disadvantage) actually received (for details see Sampson et al. 2008: 847). Based on this model, it was estimated that concentrated disadvantage reduces later verbal ability among African American children by over 4 points, over 25 percent of a standard deviation and roughly equivalent to missing a year of schooling. Neighborhood effects on verbal ability therefore appear to linger on even if a child leaves a severely disadvantaged neighborhood.

Theoretically, we would expect that influences on verbal skills would be most pronounced during the developmentally sensitive years of childhood (Shonkoff and Phillips 2000). I test this developmental interaction by estimating the influence of neighborhood disadvantage on verbal ability for the youngest African-American children assessed in the PHDCN cohorts—6 to 9 year-olds at baseline. Figure 8 presents the point estimates for four neighborhood treatment sequences. There is now a 6-point deficit in verbal ability trajectories linked to living in disadvantage at the midpoint (wave “1”) of the study (t = 2.74, p < .01). When including 12 year olds there is also a significant cohort-by-treatment interaction. If we assume for the sake of current argument that the selection model is reasonable and that the Robins “Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting” (IPTW) method adjusts for baseline (wave 0) and time-varying confounding, the implications for MTO are significant. Specifically, consider trajectories of verbal ability for black children who lived in concentrated disadvantage at wave 1. Extending the argument of Sampson et al. (2008: 852), if we randomly provided housing vouchers to this group and compared outcomes at wave 2, we might conclude that there are no neighborhood effects because there is no difference between treatment and controls at wave 2 among those receiving treatment in wave 1 (compare bottom two lines in Figure 8). This conclusion would be incorrect, however, because it brackets the significant and substantial lagged effect of living in concentrated disadvantage compared to advantage at wave 1 (a 6 point “IQ” effect). Note also that the concurrent disadvantage effect is not significant.

Figure 8.

Trajectories of Children’s Verbal Ability in Chicago for Four Concentrated Disadvantage “Treatment” Sequences: PHDCN Longitudinal Study, Cohorts 6–9, African-Americans

It follows that MTO-type studies of adolescents who grew up in poverty may not provide a robust developmental test of the causal effect of neighborhood social contexts. To be sure, one can examine developmental interactions in the MTO but the design sets limits on how far one can push in this direction—only 14% of the interim evaluation sample was between ages 5 and 7. Fully over half were age 12 or more. Combined with the crucial fact that MTO families were selected on poverty, analyses like those in Figure 8 are constrained by design. On the positive, side, however, informative models of selection can still be applied to MTO. Revising CM’s intent, one could directly model duration of exposure to poverty, including residential moving history and complier status, late cohort randomization, and changes in life circumstances that may have influenced moves back into poverty. The resulting probability-of-treatment estimates could then be incorporated into a neighborhood causal analysis, especially for the youngest children. It is unclear whether properly specified dynamic models will (or should) come to the same conclusion as the instrumental variables approach and I am making no claims for marginal structural models as a panacea. One must make assumptions that can never be proven, including that unobserved covariates that predict outcomes are unrelated to treatment group assignment conditional on observed confounders. But the MTO instrument for duration requires assumptions too and is fallible for quite different reasons. It therefore seems that both sides stand to gain from learning more about the nature of selectivity in MTO, and that time-varying counterfactual methods can be exploited to push the question farther than it has to date (see also Morgan and Winship 2007).

SUMMARY

“At issue is one of the best controlled social science experiments—if not the best—ever conducted in a natural setting. Yet scholars disagree sharply on its evaluation. This seems to me an intolerable situation because it invites general contempt for social science research, especially from the courts, who ever more frequently are asked to accept social science research as evidence. If the professors cannot collate their interpretations, the prestige of social science is bound to suffer. For that reason, I would consider it a fitting ending to this debate if the following points might constitute, as I hope, a fair summary..”

(Zeisel 1982a:395–396)

Interestingly enough, just over a quarter-century ago the AJS hosted a similar symposium on proper methods of causal analysis for a major randomized trial in the social sciences. The arena was criminal justice, and the issue at stake was whether prisoners fared better or worse with financial payments upon release. One side proposed CM-like regression adjustments to answer the causal question (Rossi, Berk and Lenihan 1980) whereas Hans Zeisel, Ludwig et al.’s counterpart of the day, insisted on a pure and simple comparison of experimentals versus controls (Zeisel 1982b). The details are unimportant now, but how Zeisel (1982b) concluded the debate, as quoted above, is. The MTO today is—rightly I believe—the gold standard for experimental social science at the individual level, and it would be a shame if the 2008 experimental debate ended in confusion. Like Zeisel, I believe it is essential that we get social experiments right.

With that in mind, and taking a cue from Zeisel, let me humbly propose something on the order of a summary closing to this particular debate. It is my hope that both sides might agree and that my intervention points to a constructive agenda for the future. If so, we should be grateful to the authors for their collective efforts and to the journal for pushing the field to think harder.

The MTO is a major contribution to the long tradition of experimental social science. By introducing a randomized design that induces residential moves of the poor to lower poverty neighborhoods, the MTO eliminates “selection bias” on unobservables as a confounding explanation of neighborhood effects on individuals. Given ethical, pragmatic, and IRB concerns that render social experiments rare, the design is ingenious.

By design, the MTO is an individual-level intervention that offered housing vouchers to extremely poor, largely minority families. Therefore nothing can be inferred from MTO about the success or failure of neighborhood-level interventions and any generalizations about voucher effects are restricted to an important but small segment of the population.

At the individual-level among the poor, MTO has demonstrated mixed results that vary by outcome, site and subgroup—especially gender. Some effects are large (e.g. on mental health, girls’ behavior), others like adult economic sufficiency appear null. In this sense the MTO has been important in debunking simple-minded hypotheses: No simple conclusion can or should be drawn about neighborhood effects in the abstract.

The treatment of the MTO voucher induced statistically significant reductions in census tract poverty (about 8 percentage points overall) compared to the control group but within what are usually considered high poverty areas and (at least in Chicago) only for the later randomization cohorts. While over half of households who used a voucher to move through MTO (“compliers”) had tract poverty rates of approximately 20 percent in 2002, the average poverty rate was greater than 30% for both the experimental and control groups overall across sites. The MTO thus induced neighborhood differences mainly of degree not kind. There are also significant cohort interactions that need further study.

There were even smaller differences induced by MTO in concentrated disadvantage defined by the segregation of African Americans in areas of resource deprivation. Moreover, whether destination neighborhoods or duration weighted, the racial context of both controls and experimentals was still hyper-segregation and nearly identical.

Because of this intersection of poverty, race, and family structure—in Chicago as in many U.S. cities—there is no counterfactual for whites and therefore neighborhood effects of concentrated disadvantage are undefined for them. Independently, both the MTO and PHDCN studies portray, in different ways, this structural reality.

Further, there were no significant differences in the rate of change in poverty or for a host of neighborhood social processes (e.g., cohesion, closure) in Chicago—whether static or dynamic—by randomization group. As a result, the trajectories that destination neighborhoods were on turned out to be virtually identical for treatment and controls, and social organizational features of community were largely unaffected by treatment. The significance (or not) of differences does not change when complier status is adjusted.

Experimental and control families ended up in the same or similar community areas. The patterned social structure taking the “bird’s eye” view of Chicago and its environs (Figures 2, 5) reveals a near identical replication across treatment and controls. Moreover, community-area differences in social processes were not different by treatment group, nor was spatially lagged poverty or concentrated disadvantage.

By design, the MTO experiment induces neighborhood change by moving, itself a life-course event of theoretical significance. Hence moving and context are intertwined.

Because MTO subjects were selected on living in neighborhood poverty, which is durable, the early developmental effects of concentrated poverty cannot be effectively studied for adults and only in a limited way for children. For the most part, MTO tests whether exits from poverty can overcome previously accumulated deficits. Thus, the lack of MTO effects does not imply lack of durable or cumulative neighborhood effects.

Moves of a random sample (PHDCN) reproduce concentrated inequality and suggest the urban dynamics if MTO-like programs were taken to scale. “White and Latino flight” also means that the treatment is not constant and that the intervention itself may induce further neighborhood changes and by implication the concentration of disadvantage.

Using randomization as an instrumental variable requires that we invoke assumptions about voucher use, some of which, like non interdependence of social interactions in the experiment, are open to question for acts of moving. If we assume no interference among units in MTO (see fn. 18), we can estimate poverty-linked (or “bundled”) neighborhood duration effects, per Ludwig et al.’s approach. But if migration research has taught us anything, it is that moving is embedded in chain-like social networks. Selection and processes should therefore still be pursued as CM started, perhaps most effectively using time-varying counterfactual methods that exploit information on selection into treatment. Because moving is a competing causal pathway in the duration weighted models, further experimental and observational work is likewise needed to isolate the effects of moving.

Perhaps surprisingly given the specific nature of the MTO treatment in a constrained urban structure, there is still evidence of neighborhood effects (point 3) that needs further unpacking. Even modest relative reductions in neighborhood poverty predict improved mental health and girls’ behavior, which over time can cumulate to shape life outcomes. By following the youngest MTO children further in time one can also gain more leverage on developmental interactions, albeit conditioned on poverty. Overall I would conclude that the planned follow-up of the MTO is a scientifically crucial investment to make.

When randomization at the individual level is invoked and we find evidence for the influence of a voucher offer on individual outcomes, it remains unclear what mechanisms link the manipulated treatment with outcomes. Experiments do not answer the “why” question. The causes of effects and social mechanisms have to date been a black box.

In the social structure that constitutes contemporary cities, selection bias is misleadingly thought of mainly in terms of unobserved heterogeneity and statistical “nuisance.” Selection is a social process that itself is implicated in creating the very structures that then constrain individual behavior. MTO can be exploited to further study the causes of neighborhood effects and the aggregate consequences of movement for social inequality.

If this is a reasonable summary and consensus achieved, maybe the burden can now be lifted from MTO as the judge and jury of neighborhood effects writ large. Indeed, the validity of MTO depends on the question one wants answered. As a century or more of urban sociology reveals, neighborhood effects may be conceived in multiple theoretical ways at multiple levels of analysis and at varying time scales of influence. No one design captures the resulting plethora of questions.

Coda

Experiments have long been cloaked in the mantle of science because of their grounding in the randomization paradigm, the putative cure for the ills of selection. If anything, the lure of experiments is increasing in the social sciences, with new journals and societies sprouting widely in recent years20 and funding decisions that favor the experimental method falling in line. In the neighborhood effects field, the mantra is also fast becoming that experiments are “a superior research strategy” for assessing causality (Oakes 2004:1929). As important as experiments are, however, they have tended toward individual reductionism and have obscured the causes of effects and operative social mechanisms. Any deep understanding of causality requires a theory of mechanisms no matter what the experiment or statistical method employed. Estimation techniques, in other words, do not equal causal explanatory knowledge (Heckman 2005).

But theories and models are not enough either. I wish to conclude with a plea for the old fashioned but time-proven benefits of theoretically motivated descriptive research and synthetic analytic efforts. After all, observational research will continue to be the workhorse of social science so we might as well get it right too. Experimentalists often forget that some of the most scientific theories around, Darwin’s natural selection being just one, were derived from systematic observation interacting with theory. Lieberson and Lynn (2002) argue that sociology has lost its way in trying to mimic a classical physics-like focus on determinism, whereas instead we should think more like evolutionary biologists. As they note (p. 1), Darwin’s theory was constructed not in a lab or using an experiment but under conditions much like those faced by social scientists—by “drawing rigorous conclusions based on observational data rather than true experiments” and by “an ability to absorb enormous amounts of diverse data into a relatively simple system.” Many causal conclusions, including the consensus that smoking causes cancer, have come about after years of careful observational research linked to rigorous thinking about causal mechanisms. The early discovery of penicillin and the cause of cholera outbreaks were similarly observation based.

Descriptive data, mapping, and pattern or configurational analyses are foundational to scientific advance, as are formal models and experimentation. Combining theory with systematic observation, I would propose that Social Causality has much to offer and does not require an experiment to bestow credibility, although surely experiments and observational knowledge together are better than either alone. Perhaps because of this symposium, we will not have to read in another 25 years hence about the sociological road not taken in the study of context.

Footnotes

I am indebted to Corina Graif for superb research assistance and Patrick Sharkey for his collaborative work on neighborhood selection. They both provided incisive comments as well, as did Nicholas Christakis, Steve Raudenbush, Bruce Western, P-O Wikström, Bill Wilson, and Chris Winship. I am grateful for the collective feedback on my ideas. I also wish to my express sincere thanks Jens Ludwig and Lisa Sanbonmatsu for their assistance in making portions of the Moving to Opportunity data available for the analyses presented in this paper.