Abstract

Numerous models explain how cells sense and migrate toward shallow chemoattractant gradients. Studies show that an excitable signal transduction network acts as a pacemaker that controls the cytoskeleton to drive motility. Here we show that this network is required to link stimuli to actin polymerization and chemotactic motility and we distinguish the various models of chemotaxis. First, signaling activity is suppressed toward the low side in a gradient or following removal of uniform chemoattractant. Second, signaling activities display a rapid shut off and a slower adaptation during which responsiveness to subsequent test stimuli decline. Simulations of various models indicate that these properties require coupled adaptive and excitable networks. Adaptation involves a G-protein independent inhibitor since stimulation of cells lacking G-protein function suppresses basal activities. The salient features of the coupled networks were observed for different chemoattractants in Dictyostelium and in human neutrophils, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for eukaryotic chemotaxis.

Introduction

Chemotaxis, the directed migration of cells in response to extracellular chemical gradients, plays important roles in embryonic development and wiring of the nervous system, and in critical processes in adults such as immune response, wound healing, organ regeneration, and stem cell homing. Derangements of chemotaxis underlie the pathogenesis of metastatic cancers and allergic, autoimmune, and cardiovascular diseases. While many behavioral features of chemotactic responses are shared among most motile eukaryotic cells, it is not clear to what extent the overall molecular paradigm is conserved.

Chemotaxis involves the integration of motility, polarity, and gradient sensing 1, 2. Cells move by extending protrusions stochastically. Typically they have an axis of polarity with a relatively active front and more contractile rear. Eukaryotic cells are able to sense differences in chemoattractant - in some cells such as Dictyostelium amoeba and human neutrophils as little as 2% - across their length 3-6. These cells can sense gradients over a range of ambient concentrations because they are able to adapt to the average level.

A series of conceptual models have been proposed to explain one or the other of these features of chemotaxis 2. Excitable networks (ENs) incorporating a variety of feedback schemes account for the stochastic behavior during migration 7-10. Local excitation, global inhibition (LEGI) models explain the cells’ ability to respond to changes in chemoattractant but adapt when the level is held constant 11-15. Frontness-backness models lead to symmetry breaking and polarity 16-19. Alone, however, none of these models satisfactorily explains the spectrum of observations displayed by chemotactic cells. For example, ENs cannot explain adaptation to constant stimuli and LEGIs lack the dynamic behavior observed in chemotactic cells. Furthermore, none of these models can account for the multiple temporal phases displayed in the responses to chemotactic stimuli 20-25. A number of models have combined several of these features with promising results but have not been thoroughly tested 26-30.

Recently, we demonstrated that cell motility requires independent but coupled signal transduction and cytoskeletal networks 31. We found that the signal transduction network, comprising Ras small GTPases, PI3Ks, and Rac small GTPases, displays features of excitability and therefore designated it as STEN (Signal Transduction Excitable Network). Here, by eliminating multiple pathways simultaneously, we demonstrate that activation of STEN by chemoattractant is critical for chemotactic motility but not directional sensing. By examining the pattern of response to combinations of spatial and temporal stimuli with different chemoattractants, we show that STEN is controlled by an adaptive LEGI mechanism involving an incoherent feedforward topology, ruling out other proposed schemes. We show that the main features of this scheme can also explain the kinetics of activation and adaptation of human neutrophils to the chemoattractant fMLP. Since the stochastic firing of STEN serves as a pacemaker to drive cytoskeletal activity and motility, our results provide the experimental evidence supporting a new paradigm for eukaryotic chemotaxis.

Results

Activation of the STEN is essential for directed migration

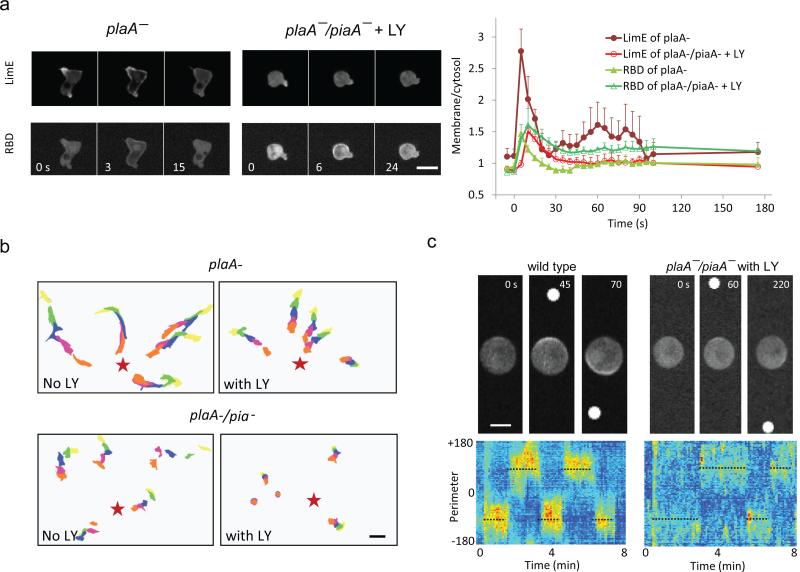

We previously reported that combined block of PI3K, PLA2 and TorC2 pathways greatly reduced random migration and as shown in Fig. 1a this combination of defects inhibits chemoattractant-elicited actin polymerization 31. In cells lacking PLA2, TorC2 subunit PiaA, and treated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, the initial peak of recruitment of actin binding protein LimE to the membrane was reduced to 30% and the secondary peaks were absent (Fig. 1a). In biochemical assays, the initial peak F-actin was reduced to 20% (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Importantly, chemoattractant-induced Ras activation rose rapidly to the same peak in plaA- cells and cells lacking all three pathways. Consistent with Charest et al.32, whereas in plaA- cells activity returned quickly to basal levels, in the cells lacking all three pathways, it declined more slowly and remained at about 20% of the peak value even 3 min after stimulation.

Figure 1. STEN is essential for directed migration.

(a) LimE-RFP and RBD-GFP were co-expressed in plaĀ or plaĀ/piaĀ Dictyostelium cells treated with 50 μM LY. The cells were stimulated with 1 μM cAMP at 0 s. Left: representative images from time-lapse videos captured at 3 s per frame. Right: quantification of membrane to cytosol ratio of RBD and LimE (mean ± s.d. of n = 3 cells each) over time. Scale bar: 10 μm. (b) Chemotaxis of cells developed for 5 hours treated with 50 μM LY or control volume of DMSO. Scale bar: 20 μm. Cell migration toward the tip of a micropipette filled with 1 μM cAMP (red stars) was recorded at 30 s intervals. Five representative cells in each movie were outlined and traced every 5 frames. (c) Cells were treated with 5 μM latrunculin. A micropipette filled with 1 μM cAMP was placed next to the cell at 20 s and switched to the opposite side of the cell several times. Top: representative images showing the direction of RBD-GFP patches in cells. White dots indicate the location of the micropipette tip. Scale bar: 5 μm. Bottom: kymograph showing the activity of RBD-GFP. Dotted lines indicate direction of the gradient.

We next examined directed migration in cells lacking these pathways. While PI3K inhibition was overcome by exposing cells to steep gradients 33, the inhibition of multiple pathways caused much stronger defects. For the majority of cells the chemotactic speed and index was reduced to 10% and 22%, respectively (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1b). However, cells in the steepest gradients (within 2 cell lengths of the tip of the micropipette) did display chemotaxis. Kortholt et al. have reported that cells lacking sGC in addition to PLA2, TorC2, and PI3K, required 200-fold steeper gradients than wild-type cells to attain the same chemotactic index 34. We examined their cells and our observations concurred with theirs although we also observed a large reduction in chemotactic speed which they did not report (Supplementary Fig. 1c)

To examine if blocking three pathways eliminates directional sensing, we treated wild type or LY treated plaA-/piaA- cells with latrunculin A, and observed RBD crescent formation as we changed direction of the chemoattractant gradient. As shown in Fig. 1c, plaA-/piaA- cells treated with LY can respond to gradient changes as quickly as wild type cells, but the intensity of the crescent is weaker than that of the wild type cells. Furthermore, there are occasional activities on the low side of the gradient, not observed in wild type cells. Taken together, the observations suggest that STEN is not required for directional sensing. However it reads out the receptor-mediated directional sensing and couples it to movement. Therefore we focused our investigation on the behavior of STEN in response to temporal and spatial stimuli in order to elucidate the mechanisms of regulation.

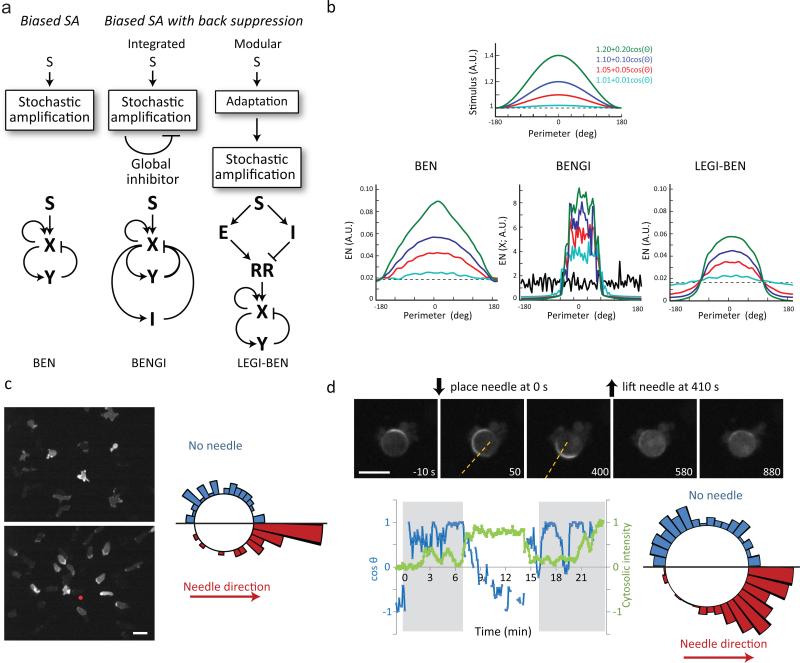

Models of directional sensing in migrating cells

Most models that can account for the stochastic protrusions observed in randomly migrating cells contain a “stochastic amplification” (SA) module. This is typically implemented as a biased excitable network (BEN) composed of coupled positive and delayed negative feedback loops. The positive loop amplifies local activities triggered by noise or external stimuli, whereas the negative feedback limits the life-time of protrusions. Chemotaxis is achieved through spatially promoting or suppressing SA by directional cues. Although models differ in details, they can be categorized into three general classes (Fig. 2a). In the simplest class, the SA module at each element around the cell is independently biased by the local level of chemoattractant so that activity is highest on the side facing the stimulus 7-10, 35. The other classes of models contain a global inhibitor to suppress the activities in the back. One class of back suppression models integrates the global inhibitor into the SA module26, 28, 36. We designate this class of models as BEN with global inhibitor (BENGI). In the prototype of the model, first proposed by Meinhardt 26, the global inhibitor acts to quickly suppress the generation of protrusions at other sites. The cells are thus intrinsically polarized, and chemoattractants work by biasing the probability of protrusion generation around the cell. In the other class of back suppression models, the chemotactic signal is first processed by an adaptive module, which subsequently biases the SA module to restrict the generation of activities to the high side of the gradient27, 29, 30. In contrast to BENGI models, the global inhibitor does not depend on the activity of the SA module. We designate this class of models as local excitation, global inhibition-biased excitable network (LEGI-BEN). An example, which uses an incoherent feedforward loop to explain adaptation and bias the activity of an excitable network, was proposed by Xiong et al.27. All three classes of models account for the ability of cells to generate greater activities toward the high side of the gradient. However, in BENGI and LEGI-BEN but not BEN models, the activities over the low side of the gradient are suppressed (Fig. 2b), and are transient when cells are exposed to uniform stimuli (see below).

Figure 2. Models of directional sensing in migrating cells and back suppression in a gradient.

(a) Three classes of models of directional sensing in migrating cells involving a stochastic amplification module (see text). The representative schemes of the three classes of models are shown below. (b) Steady-state profile of the simulated activities of the three schemes under spatial gradients of varying steepness. (c) Left: representative images of migrating Dictyostelium cells expressing LimE-RFP in the absence (top) or presence (bottom) of cAMP gradient. Right: circular histogram showing frequency of LimE patches with or without a gradient. Scale bar: 10 μm. (d) Top: frames from a time-lapse video of a Dictyostelium cell expressing PH-GFP treated with 5 μM latrunculin. Dotted lines indicate the direction of the tip of a cAMP-filled micropipette. Scale bar: 10 μm. The cosine angle between the direction of the PH activity and that of the micropipette tip is plotted on the lower left graph (blue line), along with the cytosolic fluorescence intensity normalized to the pre-stimulus level (green line). Shaded gray regions indicate durations of cAMP gradient. Bottom right: circular histogram showing frequency of PH patches from 4 cells (derived from 300 frames for “no needle”, and 510 frames for “with needle”).

Suppression at the low side of the gradient

To test experimentally whether activities are suppressed at the rear, we assessed the spontaneous production of patches of LimE-RFP, which detects newly polymerized actin37, on projections in cells moving in the absence or presence of a chemotactic gradient (Fig. 2c). In randomly migrating cells, the distribution of angles of patches was uniform, whereas cells moving chemotactically extended fewer projections away from and more toward the gradient. Similarly, in latrunculin-treated cells, the PIP3 patches were suppressed at the low, and enhanced at the high, side of the gradient (Fig. 2d). These experimental results indicate that BEN models without a global inhibitor cannot adequately explain the responses of chemotactic cells.

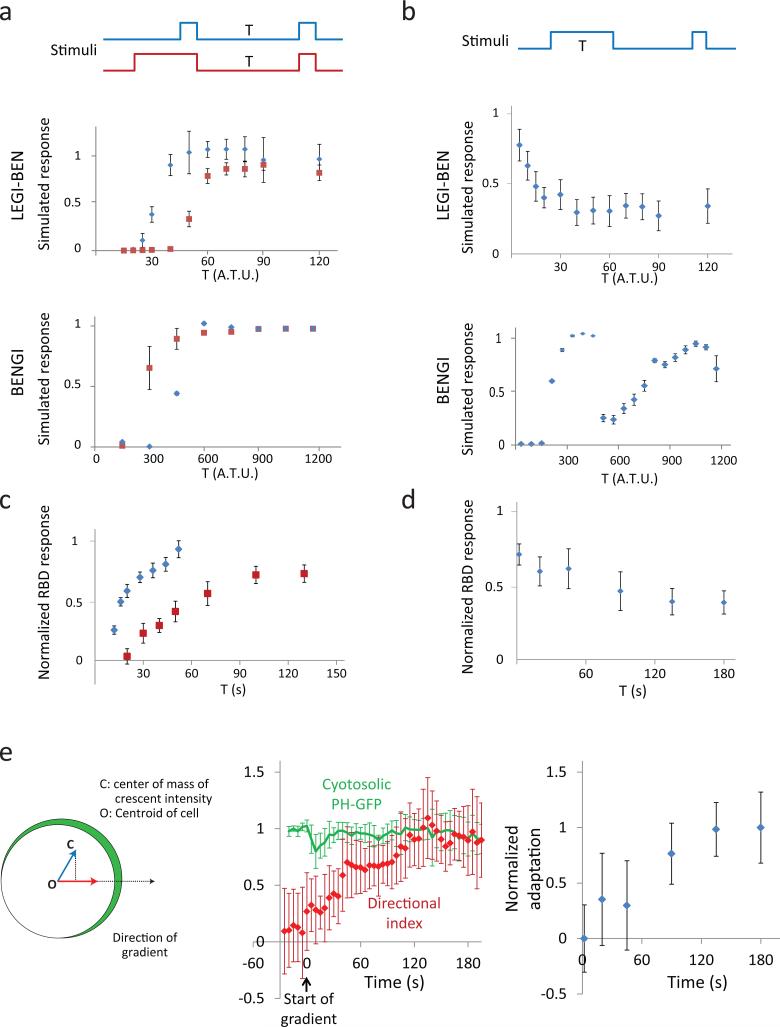

Kinetics of responses are consistent with LEGI-BEN

To distinguish the LEGI-BEN and BENGI models, we considered the kinetics of the inhibitor under persistent stimulation and simulated the Xiong et al. 27 and Meinhardt 26 models under various protocols. First, we varied the interval between an initial stimulus of short or long duration and a test stimulus. Both models displayed an absolute refractory period during which the test stimulus did not elicit a response. Lengthening the interval led to a recovery of responsiveness (Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). In LEGI-BEN, the longer initial stimulus delayed recovery of responsiveness to the test stimulus (Fig. 3a, upper, and Supplementary Fig. 2b). In striking contrast, in BENGI the longer initial stimulus accelerated the recovery of responsiveness to the test stimulus (Fig. 3a, lower). The difference can be traced to the way the global inhibitors are regulated: In LEGI-BEN the inhibitor depends on the stimulus and rises to a plateau during continued stimulation, whereas in BENGI the inhibitor is derived from the response, so it rises and falls as the latter adapts to the various stimuli. Thus, lengthening the initial stimulus increases the level of the global inhibitor in LEGI-BEN, but has the opposite effect in BENGI (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b,d). Second, we fixed the interval between an initial stimulus of increasing duration and a brief test stimulus. Again there is a dramatic difference in the behavior of the two models due to the differential regulation of the global inhibitors. In LEGI-BEN, the response to the test stimulus was initially high and decreased monotonically until the inhibitor reaches the plateau (around T = 30 A.T.U. in upper panel of Fig. 3b; see also Supplementary Fig. 2c). In BENGI the response to test stimulus was initially negligible and then increased (Fig. 3b, lower). Thereafter, the latter underwent a series of oscillations induced by secondary firings of the excitable network (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 2d).

Figure 3. Double stimulation protocols reveal distinct kinetics of adaptive and excitable networks.

(a-b) Simulated response of LEGI-BEN (upper panels) and BENGI (lower panels) to consecutive pulses with variable timing. (a) Short (2 arbitrary time unit [A.T.U.] in LEGI-BEN & 30 A.T.U. in BENGI, resp.) (blue) or long (150 A.T.U. & 2250 A.T.U., resp.) (red) pulses were followed by a variable period with no stimulus, and a short (2 A.T.U. & 30 A.T.U., resp.) second pulse. (b)The first pulse of varying duration (T) is followed by a period (50 A.T.U. & 300 A.T.U., resp.) with no stimulus, and a second short pulse. The graphs in panels (a) and (b) show the height of the response to the second pulse relative to that of the first. Error bars indicate s.d. from n=20 simulations, each. (c-d) Ras activation in developed Dictyostelium cells responding to consecutive pulses of cAMP with variable timing. Stimulation protocols for (c) and (d) are the same as those used for the LEGI-BEN model in (a) and (b), respectively. The graphs in panels (c) and (d) show the magnitude of the RBD response, defined as the peak decrease in cytosolic RBD-GFP, to the second pulse relative to that of the first. Error bars indicate s.e.m. of n=30 (blue) and 15 (red) cells for (c), and s.e.m. of n=12 cells for (d) from 2 independent experiments, respectively. (e) Comparison of kinetics of directional sensing and adaptation. Left: Directional index is defined as the projection (red arrow) of the vector (green arrow, OC) from the centroid of the cell (O) to the center of mass of crescent fluorescent intensity (C) in the direction of the gradient. Middle: Temporal profile of the directional index (red) and the mean cytosolic PH-GFP normalized to pre-stimulus level (green). A micropipette containing cAMP was introduced at 0 s. Error bar = s. d. of n = 10 cells from 3 independent experiments. Right: Kinetics of adaptation derived from (d). The values are normalized to the difference between the minimal and maximal levels of RBD responses.

To distinguish experimentally between the two models, we carried out the double stimulation experiments in Dictyostelium cells using RBD-GFP. First, we compared the rate of recovery after a short (2 s) or long (150 s) initial stimulus. As shown in Fig. 3c, in cells adapted to the long initial stimulus, the recovery is delayed. Second, we increased the duration of the initial stimulus while keeping the recovery interval fixed at 50 s, to allow the refractory period to resolve. As shown in Fig. 3d, the response to the test stimulus decreased as the duration of the initial stimulus was increased from 10 s to 3 minutes. These results support the LEGI-BEN model and rule out BENGI.

Since it suppresses activities at the low side, the timing of the global inhibitor in each model also dictates the response to gradients. In BENGI, the global inhibitor is fast compared to the negative feedback in the excitable network in order to suppress activities away from the high side of the gradient before they become self-catalytic 26. In LEGI-BEN the inhibitor, and therefore the directional response, develop slowly. As shown in Fig. 3e, when the gradient was first applied to cells, there was a global response that was followed by the gradual appearance of a crescent in the direction of the gradient. This timing matched that of adaptation determined from the double stimulation experiments. Again, this result supports LEGI-BEN and rules out BENGI.

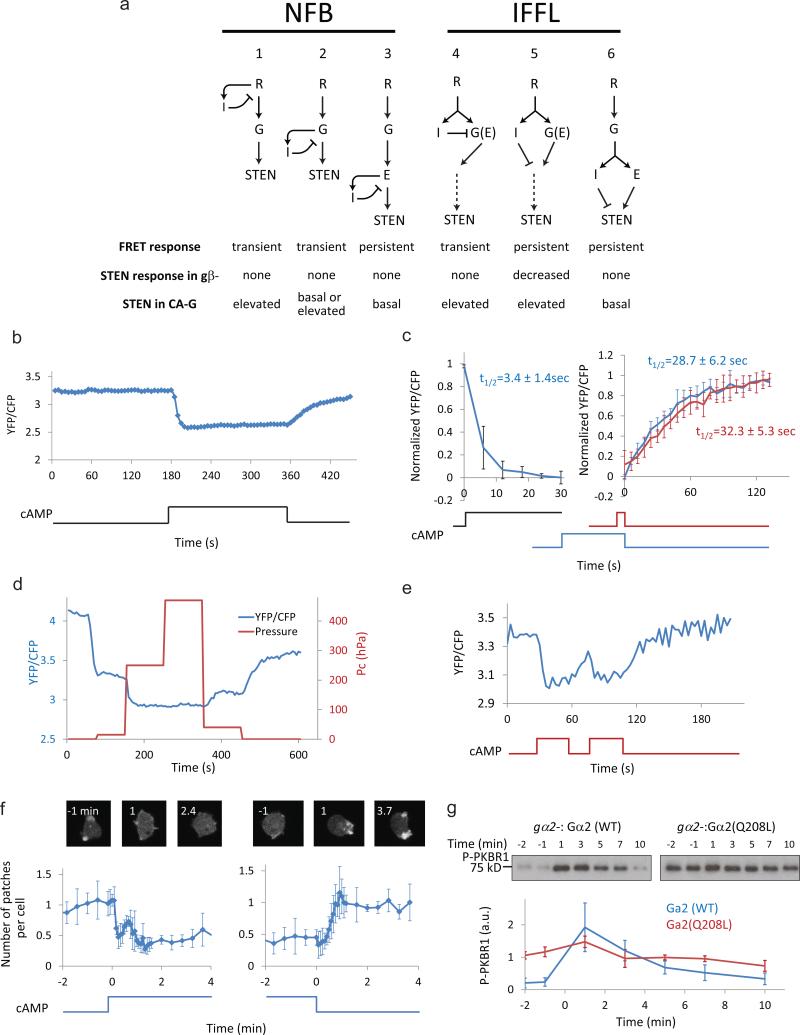

The role of G-proteins in the LEGI module

Having found experimental evidence for LEGI-BEN, we next investigated the architecture of the LEGI module. Although we implemented LEGI as an incoherent feed-forward mechanism, directional sensing and adaptation could also be achieved with a negative feedback loop 38, 39. We considered three possible NFBs and three IFFLs in which the inhibitor acts at different points relative to the G-protein (Fig. 4a). For each topology we considered 1) the kinetics of chemoattractant-mediated G-protein activation; 2) the response of STEN to chemoattractant in the absence of G-protein function; 3) the effect of constitutive G-protein activation (Fig. 4a). We carried out experiments to test these predictions.

Figure 4. Architecture of the LEGI module.

(a) Network topologies that achieve adaptation through negative feedback loops (1-3) or incoherent feedforward loops (4-6). The predicted responses of G-protein FRET to continued stimulation, the response of STEN to stimulation in gβ- cells, as well as the effect of constitutive activation of G-protein (CA-G) on STEN, are shown at the bottom. (b) Representative response of single-cell G-protein FRET. The ratio between emissions of Gα2-Cerulean (CFP) and Gβ-Venus (YFP) was used as surrogate readout for FRET. (c) Kinetics of G-protein FRET in response to cAMP stimulation and removal. The YFP/CFP ratio was normalized to pre-stimulus levels. Left: Response to cAMP stimulation (mean ± s.d. of n = 7 cells). Right: comparison of FRET recovery after removal of short (10 s) stimuli (red, mean ± s.d. of n = 12 cells) or long stimuli (90-180 s) stimuli (blue, mean ± s.d. of n = 5 cells stimulated for 90, 135, 135, 120, and 180 s, respectively). The half-times were obtained by fitting data sets to exponential curves by non-linear least square method using Gnuplot (http://www.gnuplot.info/). (d) Representative example of graded G-protein FRET response of a single Dictyostelium cell to changing levels of cAMP. The YFP/CFP ratio was plotted along with the compensation pressure (Pc) applied to a cAMP-filled micropipette used to deliver the stimulus. (e) Representative example of G-protein FRET response to two 30 s stimuli separated by 15 s. (f) Responses of gβ- cells to cAMP. gβ- cells expressing LimE-RFP and cAR1 were developed for 5.5 hour before stimulation with 1 μM cAMP in ibidi chamber (http://ibidi.com/). Representative cell images (top) and quantification of number of patches per cell (below, (mean ± s.d. of n = 4 experiments) are shown. (g) Constitutively active G-protein leads to persistent phosphorylation of PKBR1. Top: Developed gα2- cells expressing cAR1 and either wild-type Gα2 or Gα2(Q208L) were stimulated with 1 μM cAMP at 0 min. Samples were taken at indicated time points and probed with anti–phospho-AL antibody58. Bottom: Quantitative densitometry of phosphorylated PKBR1 normalized to the average intensity of the Gα2(Q208L) samples (mean ± s.d. of n = 4 experiments).

First, at the single cell level, G-protein activation, monitored by the loss of FRET between Gα2-CFP and Gβ-YFP40, was persistent (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, loss of FRET occurred with a half time of ~3 s, whereas the recovery of FRET after removal of stimulus occurred at a slower rate, with a half time of ~30 s. The latter was independent of the duration of the stimulus (Fig. 4c), in contrast to recovery kinetics of RBD responses (Fig. 3c). Thus, re-association of G-protein subunits cannot account for the pattern of recovery from adaptation. Furthermore, the response was graded as the stimulus was increased (Fig. 4d) and was triggered immediately when the stimulus was removed for 15 s and reapplied (Fig. 4e). Together these results suggest that G-protein dissociation neither adapts nor displays excitable behavior, ruling out topologies 1, 2 and 4.

Second, we stimulated gβ- cells expressing LimE-RFP with chemoattractant. As shown in Fig. 4f, the number of patches of LimE-RFP gradually decreased and remained low during persistent stimulation. The cells became less motile, extended fewer projections and rounded up (Supplementary Fig. 3a). When the stimulus was removed, the pre-stimulus behavior gradually resumed. This result can only be explained by topology 5, which allows a G-protein independent inhibitory signal to affect STEN and downstream events. Consistently, the kinetics of LimE-RFP decrease is similar to those of directional sensing and adaptation (Fig. 3e). To further test topology 5, we examined the effect of a constitutively active mutant, Gα2(Q208L). While gα2- cells expressing the wild-type Gα2 responded transiently to cAMP stimuli, there was a persistent, non-adapting elevation of phosphorylated PKBR1 in cells expressing Gα2(Q208L) (Fig. 4g, see also Supplementary Fig. 3b-f). Taken together, these results suggest that the transient response to chemoattractant is mediated by an incoherent feedforward mechanism involving G-protein activation and G-protein independent inhibition.

Responses of the signaling network in immobilized cells

Chemotactic cells are able to sense shallow gradients in the face of increasing ambient concentrations of chemoattractants. The LEGI-BEN scheme effectively accounts for this behavior because excitation and inhibition are specified by the current level of the stimulus and balance each other at steady state. We compared simulated and experimental results to explore this property. First, upon the initial addition of a gradient, the simulation generated a global response before settling to dynamic activity toward the high side. Addition of a higher stimulus generated another transient global response followed by biased stochastic activities (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Experimentally, when immobilized cells were exposed to chemotactic gradients, PIP3 accumulation displayed similar patterns of global accumulation and dynamic patches (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 4b). Second, the simulation predicted that a brief stimulus would trigger the same response in cells fully adapted to a steady level of chemoattractant as it does in naïve cells (Fig. 5c). As shown in Fig. 5d, in cells pretreated with 100 nM cAMP a test stimulus elicited the same response as untreated cells. The absence of response observed following pretreatment with the saturating stimulus is expected since the test stimulus produced no further increase in receptor occupancy.

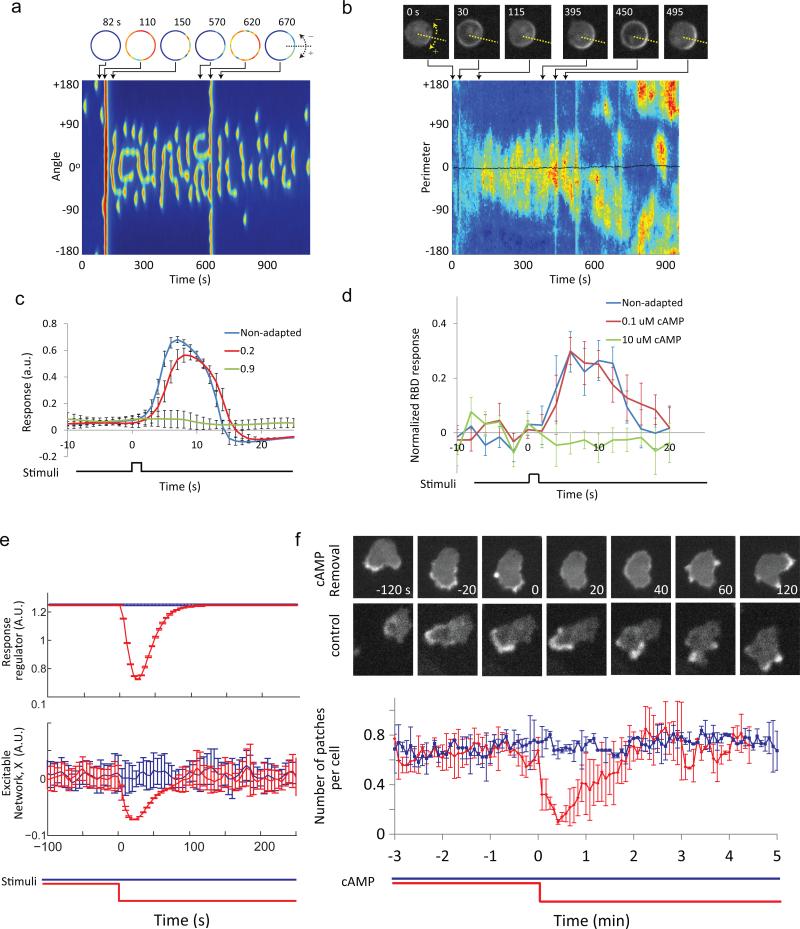

Figure 5. LEGI-BEN model accounts for response to chemoattractants of immobilized cells.

(a) Simulated activity of LEGI-BEN. The gradient (highest concentration at perimeter 0° in kymograph) was introduced at 100 s. At 600 s, the stimulus was increased globally while maintaining the spatial gradient. Snapshots of cell activity are shown above. The plotted activities are those of Y in the EN; plotting X shows similar results 27. (b) Kymograph showing “dancing” crescents of a latrunculin-treated Dictyostelium cell expressing PH-GFP. A gradient was initiated at 15 s, and global stimuli of 1 nM, 10 nM, and 100 nM cAMP were added at 450 s, 540 s, and 730 s, respectively. The plotted activities in kymograph reflect the ratio of local cortical PH-GFP to mean cytosolic intensity. Note that after addition of 10 nM cAMP, the PH-GFP crescents are no long biased since the gradient generated by the micropipette became negligible. In snapshots of cells (top) the direction of gradient was indicated by dotted lines. (c) Simulated responses (mean ± s.d. of the level of X, the activator in the EN, for n = 10 simulations) of LEGI-BEN to a short (2 s) pulse of magnitude 1 AU, assuming prior stimulus levels (basal, 0.2 and 0.9 A.U.). (d) Decrease in cytosolic RBD (mean ± s.d. for n=8 cells) in developed Dictyostelium cells (immobilized with 5 μM latrunculin A) in response to a short cAMP stimulus with or without prior adaptation to indicated cAMP concentration for 3 min. (e) Simulation of stimulus removal in LEGI-BEN. The system was allowed to reach steady-state before the stimulus was removed at 0 s (red) or continued (blue). Shown are the responses of the LEGI response regulator and EN (mean ± s.d. of n=10 simulations). (f) LimE-RFP response to removal of stimulus. Dictyostelium cells were incubated in 50 μL DB buffer containing 0.1 μM cAMP for 6 minutes followed by dilution with 20× volumes of buffer without (cAMP removal) or with 0.1 μM cAMP (control). Top: Snapshots from time-lapse videos. Scale bar: 10 μm. Bottom: Quantitation of LimE activity (mean ± s.d. of n = 50 cells; 3 experiments) in cAMP removal (red) and control (blue) experiments.

According to the LEGI-BEN model, removal of a uniform stimulus will lead to transient suppression of the STEN activity: The inhibitor drops more slowly than the excitor and the level of the response regulator transiently dips below its basal level (Fig. 5e). To test this, we pretreated cells expressing LimE-RFP with cAMP for ~6 min and then suddenly removed the stimulus (Fig. 5f). The addition of the stimulus generated the typical series of responses and then the cells resumed pre-stimulus behavior after 5 minutes. When the stimulus was removed, LimE-RFP disappeared from the membrane for an extended period and the cells retracted. Then the cells gradually resumed random migration with LimE-RFP appearing on protrusions. Similar transient suppression was observed for RBD, indicating this behavior reflects the inhibitory effect of LEGI on STEN (Supplementary Fig. 4e).

LEGI-BEN in response to different chemoattractants

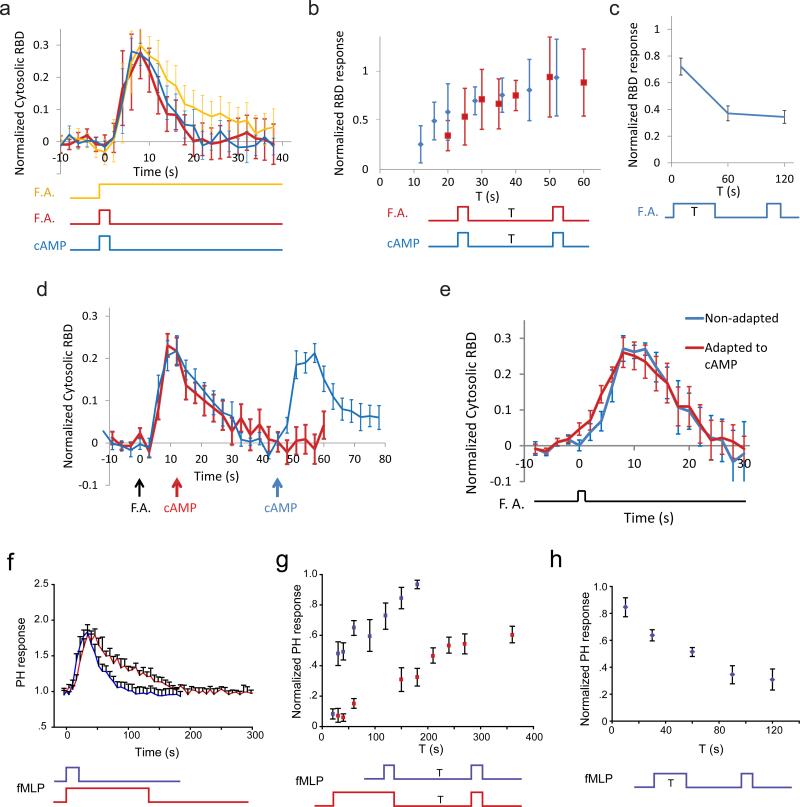

The experiments shown so far were carried out in developed Dictyostelium cells stimulated with cAMP. To test whether the LEGI-BEN model also accounts for responses to other chemoattractants, we carried out folic acid stimulation in less differentiated cells. These cells are chemotactic toward both folic acid and cAMP. The profiles of responses to folic acid were remarkably similar to those induced by cAMP (Fig. 6a). First, the responses to short and long folic acid stimuli were nearly identical. Second, when cells were stimulated with two brief folic acid stimuli separated by increasing durations, they displayed nearly the same refractory period (Fig. 6b). Third, cells pretreated with longer initial stimuli were less responsive to second stimuli (Fig. 6c), suggesting that adaptation also occurs for folic acid responses.

Figure 6. LEGI-BEN for folic acid in Dictyostelium and fMLP response in human neutrophils.

(a-c) Ras activation in Dictyostelium cells stimulated with folic acid. (a) Responses (n=32 cells each) to 2 s (red) and long (orange) stimuli. The response to a 2 s cAMP stimulus (n=10 cells, blue) is plotted for comparison. (b) Responses (n=15 cells, red) to the second 2 s stimulus applied after variable intervals (T) following the first 2 s stimulus. The response to cAMP stimuli (n=30 cells, blue) is plotted for comparison. (c) Responses (n=20, 19, 18 cells, respectively; 3 experiments) to a 2 s folic acid stimuli applied 50 s after first stimuli of 10, 60, and 120 s. (d) Ras activation in Dictyostelium cells stimulated with 5 μM folic acid at 0 s followed by 0.3 μM cAMP at12 s (red, n=15 cells; 4 experiments) or 45 s (blue, n=13 cells; 5 experiments). (e) Ras activation in Dictyostelium cells responding to folic acid with or without prior adaptation to cAMP. Non-adapted cells were stimulated by 2 s folic acid (blue). The same cells were then treated with 200 μM cAMP for 3 min and stimulated with a 2 s folic acid pulse (red; n=12 cells; 2 experiments). For (a) to (e), responses were defined as the peak cytosolic RBD-GFP decrease normalized to the pre-stimulus cytosolic levels (a, d, e) or to the first response (b, c). (f-h) PH-GFP responses in human HL60 neutrophils responding to fMLP. (f) Responses (n = 4 cells each) to 10 s (blue) and 120 s (red) stimulation. (g) Responses (n = 5 cells each) to a second 10 s stimulation administered after various intervals (T) following first stimuli of 10 s (blue) or 120 s (red). (h) Responses (n=5 cells each) to a second 10 s stimulation administered 150 s after removal of the first stimulation of various durations (T). In all experiments, HL-60 cells were immobilized with the JLY cocktail (see Methods)59. The responses were defined as peak changes in the (membrane + cytosol)/(cytosol) of PH gray values. For (g) and (h), normalization was to the responses to the first stimuli. Error bars: s.d. for a, b and s.e.m. for c-h.

To determine whether cAMP and folic acid activate the same excitable network and whether adaptation to one causes adaptation to the other, we paired stimuli. First, cells responded to both folic acid and cAMP stimuli that were separated by 45 s (Fig. 6d, blue line), but when the separation was 12 s, the second response did not occur (Fig. 6d, red). Thus, cells do not respond to cAMP during the refractory period induced by folic acid. Second, we pretreated the cells with 10 μM cAMP for 3 min then applied a brief folic acid stimulus. The folic acid stimulus elicited a response similar to that observed in untreated cells (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Movie 1). Taken together, these results suggest that the same STEN is activated by the two stimuli but that cells adapted to one can still respond to the other.

Conservation of LEGI-BEN scheme in human neutrophils

We next tested whether the features of LEGI-BEN are conserved in HL-60 neutrophils, derived from the human promyelocytic leukemia cell line. Immobilized neutrophils displayed dynamic flashes of PH-Akt-GFP that were 2-5μm in diameter and lasted 50 to 150 s (Supplementary Fig. 5a-c, and Movie 2). The membrane marker C5aR-RFP did not show changes in intensity. Several other tests also indicated that the signaling activities are excitable. First, 10 s and 120 s fMLP stimuli induced responses with the same rise time and peak magnitude (Fig. 6f) and as in Dictyostelium the response to the longer stimulus had a slower declining phase. Second, with two short (10 s) stimuli separated by increasing intervals, the second response showed a gradual recovery when the interval between stimuli was increased (Fig. 6g, blue). Taken together, the spontaneous flashed, “all-or-nothing” responses to short stimuli, and the refractory period suggest that signal transduction activities in neutrophils are excitable.

Using the protocols outlined in Figure 3, we tested whether HL-60 cells display adaptation. First, when the interval between adapting and test stimuli was fixed, increasing the duration of the adapting stimulus diminished the response to the test stimulus (Fig. 6h). Second, in cells pretreated with short or long initial stimuli, the long pretreatment delayed the subsequent rate of recovery (Fig. 6g, red). Together these results suggest that responses of HL-60 cells, as in Dictyostelium cells, are consistent with the predictions of the LEGI-BEN model.

Discussion

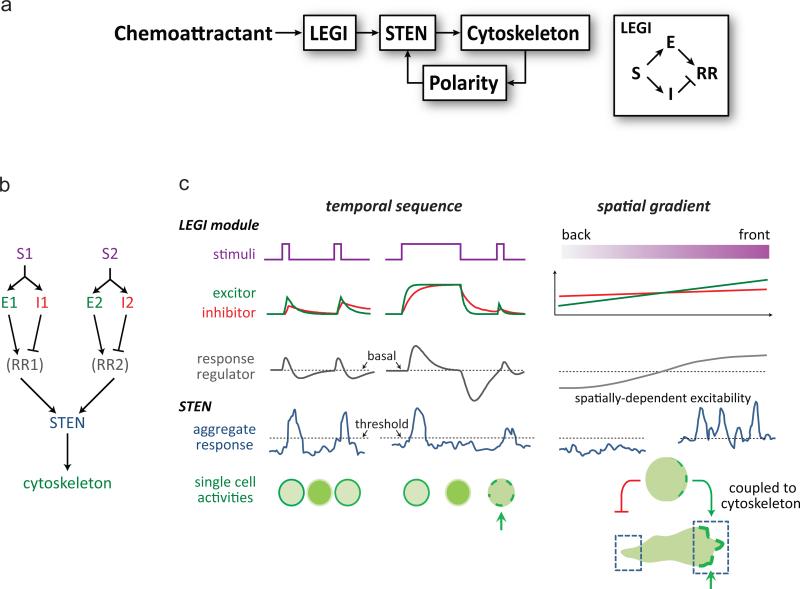

A number of theoretical models have attempted to explain the remarkable ability of chemotactic cells to detect and migrate along very shallow chemoattractant gradients, even in the presence of high background levels (reviewed in 41). We have focused our attention on models that incorporate stochastic activities since many investigators have noticed that the signal transduction and cytoskeletal activities display features of excitability such as spontaneous patches and propagating waves 27, 31, 42-47. In this study we provided evidence favoring the LEGI-BEN model over other existing schemes. First, we ruled out models that do not incorporate back suppression since the spontaneous activation of Ras and PI3K are repressed at the back of the cells in a gradient. Second, we ruled out models that integrate a global inhibitor into the excitable network based on the pattern of responses to paired stimuli. Our evidence suggests that the adaptive module involves a G-protein dependent excitor and independent inhibitor forming an incoherent feedforward mechanism. A feed-forward mechanism has been proposed for the kinetic of Ras activation by Takeda et al. 14, although the conclusion was drawn from analyzing the termination of responses within 30 s of stimulation, before adaptation was complete (Fig. 3d). Note that the LEGI-BEN scheme we present here does not take into account polarity, which is seen in non-stimulated, randomly migrating cells. Rather it focuses on the role of directional sensing in regulating STEN. A complete model involving LEGI, STEN, cytoskeleton and polarity is shown in Fig. 7a 48.

Figure 7. Summary of responses of LEGI-BEN to temporal and spatial stimuli.

(a) Modular view of the chemotaxis signaling pathway. The LEGI module senses chemoattractant stimuli and biases the activity of the STEN, which regulates the cytoskeleton. Polarity, which depends on the existence of an intact cytoskeleton, provides feedback by further biasing the STEN's activity 48. The LEGI module (right) includes excitor (E) and inhibitor (I) elements that are regulated by receptor occupancy (S) and regulate the response regulator (RR) in complementary ways. (b) Response to multiple stimuli. Chemoattractants S1 and S2 activate different LEGI modules, which in turn regulate the same STEN that is coupled to the cytoskeletal network to mediate chemotaxis. (c) Summary of responses to temporal sequences and spatial gradients of chemoattractant. On the left, two stimuli separated by an interval trigger rapid changes in the excitor and slower changes in the inhibitor, which control the level of the response regulator. When the level of the response regulator crosses the threshold it triggers the activation of STEN, which is all-or-none for each element on the membrane but may not be uniform across the whole cell (arrows) 31. In a stable gradient, the excitor and inhibitor are generated by the local level of receptor occupancy but since the inhibitor has a larger dispersion range (determined by its the diffusion rate and half-life60) its steady state distribution is shallower than that of the excitor. Consequently, the response regulator is higher than the threshold at the front and lower than the threshold at the back. This promotes persistent STEN activity at the front and when coupled to the cytoskeleton biases migration.

Activities involving multiple signal transduction pathways are critical for chemotaxis34, 49, and cells can still chemotax with disruption of individual pathways 50-52. We have shown previously that cells with disruptions in multiple pathways do not move in the absence of chemoattractant 31. Here we found that blocking multiple pathways prevents actin polymerization in response to chemoattractant. Furthermore, these cells cannot carry out chemotaxis because they do not move unless exposed to extremely steep chemoattractant gradients. Independent cell lines created in different laboratories with multiple signal transduction pathways disrupted displayed similar behavior. While the STEN is required for chemotaxis, its excessive activation impairs the process 48, 53. Consistent with Veltman et al. 52, we found that treatment with a low dose LY improved chemotaxis of partially developed cells (Supplementary Fig. 1d), which, in the absence of LY, display more spontaneous patches of PH-GFP compared with more developed cells (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

Although the LEGI inhibitor is unknown, our results indicate that it is generated by occupancy of the receptor and independently of the G-protein. First, stimulation of cells lacking the Gβ subunit elicits no response, only a slowly developing suppression of basal cytoskeletal activity and pseudopod extension which is reversed upon removal of the stimulus. Second, constitutively active Gα generated a persistent, non-adapting increase of PKBR1 phosphorylation, indicating that adaptation is not derived from G-protein activation. We did not observe a robust negative effect of stimulation in these cells, presumably because the activity is too strong to suppress. Third, when a cell has been adapted, removal of the stimulus causes suppression of basal RBD and cytoskeletal activity (Fig. 5f). We speculate that the inhibitor decays more slowly than the excitor and this sends a negative signal to the STEN. Clearly these features of adaptation as well as the fact that loss of G-protein FRET persisted as long as the stimulus was present are inconsistent with current models in which receptor phosphorylation uncouples interaction with G-proteins 54.

We provided evidence that two chemoattractants for Dictyostelium, folic acid and cAMP, activate the same STEN but they have distinct directional sensing, adaptive networks. Even though folic acid and cAMP act through Gα4 and Gα2 55, 56, respectively, cAMP does not induce a response during the refractory period induced by folic acid. In addition, we extend earlier observations that Dictyostelium cells adapted to either folic acid or cAMP remain responsive to the other chemoattractant 57. By examining the responses at the single cellular level, we prove that this phenomenon occurs in individual cells and is not due to heterogeneity in responsiveness to cAMP and folic acid in different subsets of cells. We speculate that different chemoattractants in general activate the STEN through different LEGI modules (Fig. 7b), although some components of the LEGI may be shared.

The response of STEN to combinations of temporal and spatial stimuli can be explained by the LEGI-BEN model (Fig. 7c). First, it can explain the responses to paired stimuli. The example shown in the figure illustrates the behavior of LEGI and STEN during the protocol designed to measure the time course of adaptation (Fig. 7c, left). A brief initial stimulus has little effect on the test stimulus separated by a sufficient interval, so that the response regulator causes STEN to cross the threshold equally. However, a longer initial stimulus generates inhibitor which has not dissipated when the test stimulus is applied so the amount of response regulator generated barely allows the STEN to cross threshold. Similar diagrams can explain the protocol for monitoring deadaptation. Remarkably, these features of LEGI-BEN could not only explain responses of signal transduction network in Dictyostelium but also in human neutrophils, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for eukaryotic chemotaxis. Second, the LEGI-BEN model explains how spatial gradients of chemoattractant can bias the STEN (Fig. 7c, right). In a gradient the excitor is greater than the global inhibitor at the front, and less at the back. This causes the response regulator to be above or below its basal level at the front or back, respectively. In turn, STEN activity is higher at the front and more easily crosses the threshold while at the back it is suppressed. When the background level of chemoattractant is changed, the adaptation mechanism ensures that the response regulator returns to the same spatial profile, which keeps the system within the range of excitability of the STEN.

Methods

Cells

Wild-type Dictyostelium discoideum cells of the AX2 strain, obtained from the R. Kay laboratory (MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, UK), were used in this study. The aca-, gβ-, and plaA-/piaA- cells were described previously31, 61, 62. sGC– and sGC–/plaA–/piaA– cells were obtained from A. Kortholt and P. Van Haastert (University of Groningen). Cells were transformed with plasmids encoding RBD-GFP, PH-RFP, Gα2-CFP, Gβ-YFP, or LimE-RFP by electroporation and maintained in HL-5 medium containing G418 (20 μg ml−1) or hygromycin (50 μg ml−1) at 22°C. For folic acid stimulation experiments, cells were washed in development (DB) buffer (5 mM Na2HPO4, 5 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM MgSO4, and 0.2 mM CaCl2) and shaken in suspension for 1-2 hours at a density of 2×107 cells per ml. For cAMP stimulation experiments, cells were developed for 5 hours by pulsing with cAMP every 6 minutes in development buffer at a density of 2×107 cells per ml.

HL-60 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing GlutaMAX-1 (Gibco, life technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco, life technologies, Grand Island, NY), 100 U ml−1 penicillin, and 100 mg ml−1 streptomycin in 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Differentiation into neutrophil-like cells was induced by adding 1.3% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) into culture medium for 5 days. HL-60 cells were infected with FUW lentivirus (a gift from Dr. Christopher Cooper in Stephen Desiderio's Lab) carrying PH-Akt-GFP or C5aR-RFP. Positive cells are selected by FACS.

Microscopy

Confocal microscopy was carried out on a Leica DMI6000 inverted microscope equipped with Yokogawa CSU10 spinning Nipkow disk with microlenses and illuminated by a Kr/Ar laser was used.

Dictyostelium cells were transferred to Lab-Tek II chambered cover glasses (Thermo Scientific) containing developmental buffer before imaging. Latrunculin A and LY294002 were diluted to the final concentration from a stock solution in DMSO (concentration: 1 mM for latrunculin A and 50 mM for LY294002). Stimulation was carried out by lowering a micropipette containing chemoattractants (10 μM cAMP or 100 μM folic acid) to the viewing field using a FemtoJet Microinjector controlled by a micromanipulator (Eppendorf). Based on the temporal profile of fluorescence from a micropipette filled with Alexa Fluor 594, the change in the concentration of chemoattractants occurs with a half-time of about 1.3 s within the viewing field. To eliminate the confounding effect of photosensitivity in adaptation, cells were not imaged during prolonged first stimulation in double stimulation experiments. Imaging of cells was started 10 s before the second stimulus was applied.

HL-60 neutrophils were spun down, washed with mHBSS medium (137 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 10 mg ml−1 glucose, and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2), resuspended with mHBSS containing 0.2% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and then seeded on Lab-Tek chambered cover glasses (NUNC, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY) pre-coated with 100 μg ml−1 human fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cells were incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes, rinsed twice with mHBSS medium, and then bathed in mHBSS containing 0.2% BSA before imaging. JLY cocktail treatment59 was done by addition of Y27632 (final concentration: 10 μM), incubation for 10 min, followed by simultaneous addition of Latrunculin B and Jasplakinolide (final concentrations 5 μM and 8 μM, respectively). Stock concentrations are 25 mM for latrunculin B (in DMSO), 1 mM for Jasplakinolide (in DMSO), and 10 μM for Y27632 (in ddH2O). Stimulation was carried out by lowering a micropipette containing 10 μM fMLP to the viewing field using a FemtoJet Microinjector controlled by a micromanipulator (Eppendorf).

FRET

Detailed protocol for FRET experiments has been described previously58. Briefly, FRET experiments were carried out with either an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope illuminated by a Kr/Ar laser (457 nm) source or a Nikon Eclipse TiE microscope illuminated by a diode laser (440 nm). Images were acquired by a Photometrics Cascade 512B intensified CCD camera controlled by MetaMorph (UCI) or a Photometrics Evolve EMCCD camera controlled by Nikon NIS-Elements. A Dual-View system (Optical Insights, LLC) was used for simultaneous imaging of CFP and YFP fluorescence in doubly labeled cells. The ratio between background-corrected YFP and CFP signals was used as surrogate for FRET efficiency.

Image analysis

Images were analyzed with ImageJ (NIH). The responses to chemoattractant stimulation were calculated from the decrease in the mean cytoplasmic fluorescence, as described in figure legends.

The kymographs of the activities in the latrunculin-treated cells were created using the image processing toolbox of Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA). First, the fluorescent intensities of all frames in the movies were summed. The resultant composite image was segmented using adaptive thresholding and fitted to a circle. Thereafter, each frame of the movie was individually segmented to find the centroid of the cell at that frame. Using the calculated centroid, the intersection of a ray with circles of the given radius (plus or minus 3 pixels) was computed. From this set of pixels, the maximum intensity of was assigned to that angle. This was repeated for rays spaced one degree apart, creating an 360 times #frames matrix, which was then plotted as an intensity map.

Immunoblotting

Dictyostelium cells developed for 5-6 hours were treated with 5 mM caffeine in development buffer and shaken for 20 minutes. Cells were then pelleted and resuspended in cold development buffer at 2 × 107 cells ml−1. Cells were stimulated with 1 μM cAMP on ice and samples taken at various time points were lysed in SDS sample buffer. PKBR1 phosphorylation was detected as described previously 63. Briefly, proteins were separated on 4-15% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% skim milk in TBST, the membranes were probed with anti phospho-PKC (pan) antibody (190D10 rabbit monoclonal antibody, Cell Signaling #2060, 1:2000 dilution in TBST with 5% BSA at 4°C for 16-20 hour), followed by detection with anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (GE Healthcare Life Sciences NA934V, 1:5000 dilution in TBST at room temperature for 1 hour). An example of uncropped blot is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3f.

Computer simulation

Simulations of the coupled local-excitation, global-inhibition (LEGI) biased-excitable network (EN) were carried out as described previously 27, 48. Briefly, the LEGI mechanism is given by partial differential equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where S, E, I and R describe the levels of receptor occupancy, the local excitation, global inhibition, and response regulator, respectively. Note that the equation for the response regulator differs from those previously implemented. The parameters ke and ki describe basal levels of excitation and inhibition. Under spatially uniform stimulus, S0, the steady-state level of the response regulator is

| (4) |

Perfect adaptation requires that this be independent of S0, which can be achieved if ke and ki are both small relative to (kE/k-E) S0 and (kI/k-I) S0, respectively. We make this assumption, and set the “basal” level of S0 at 0.1 A.U. Unless stated, pulses where of height 1.A.U.

The excitable network is implemented as an activator (X)-inhibitor (Y) system, satisfying the stochastic partial differential equations:

| (5) |

| (6) |

Both components in the excitable network diffuse spatially, with diffusion coefficients DX and DY, respectively. The signal U, which is used to bias the activity of the excitable system, incorporates three components: a basal level of activity (B), a stochastic component (N), and a contribution from the LEGI response regulator (R). The effect of each of these is additive: U = B + N + λ(R − Rinit). The stochastic component is modeled as zero mean, white noise process with variance one.

The simulations were carried out by solving the five differential equations using the method of lines – whereby partial differential equations are converted into ordinary differential equations by discretizing the spatial variable and approximating the Laplacian with central differences. A one-dimensional domain with periodic boundary conditions (representing the boundary of a two-dimensional, circular cell) was discretized using 314 elements. Because the LEGI mechanism is deterministic, the three equations of this subsystem were solved using the Runge-Kutta ode45 solver in Matlab. Once these solutions were obtained, the stochastic differential equations of the EN were solved using the SDE toolbox for Matlab: ( http://sdetoolbox.sourceforge.net). Time steps were set to 0.025 s.During the simulations, all parameters used (except B, λ and Rinit) were varied stochastically around the perimeter of the cell by selecting from a uniform distribution in the range k(1±δ) where k is the nominal value of the parameter, and δ=0.05. Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the nominal parameters used.

Simulations for the BENGI class use the model of Meinhardt 26:

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

As above, the spatial aspects were achieved through the method of lines, using a discretization of 90 points around a circle. Parameters used are as in Neilson et al. 28, which match those of Meinhardt except for small differences; e.g. non-zero diffusion terms DX and DY (see Supplementary Table 1). Note that the time scale of these simulations is considerably slower than either the LEGI-BEN or experiments, so that all the time intervals of Fig. 3 were modified so that the two systems had compatible dynamics.

The equations of the BENGI model were implemented in two different ways. Matlab's ode15s solver was used in the absence of noise (N=0). To simulate the effect of noise, we assumed that N(t) was a Gaussian, white noise process with mean ½ and variance 1/12. The simulation was then run in the SDE toolbox as above. These numbers were used to match the statistics of the noise used in the Meinhardt model (which assumes a uniformly distributed random variable between 0 and 1 at each time step).

Statistical analysis and repeatability of experiments

Statistical significance and P values were determined using the two-tailed Student's t-test. Mean values ± either S.D. or S.E.M. were reported as indicated in figure legends.

Two independent experiments were performed for Fig. 1a, 3c, 3d, 5d, 6a, 6b, 6h, and supplementary Fig. 3f; three experiments for Fig. 5f, 6c, 6f, 6g, and supplementary Fig. 1c, 3d, and 4d; four experiments for Fig. 4c, 4g, 6d, and supplementary Fig. 4e; five experiments for supplementary Fig. 1e; and six experiments for supplementary Fig. 1a. Statistics were derived by aggregating the n numbers noted in each figure legend across independent experiments.

Representative images associated with Fig. 1a, 2c, 2d, 4g, 5f, and supplementary Fig. 3d, 3f, 4d, and 4e are shown along with statistics.

Representative images are also used for Fig. 1c, 5b, supplementary Fig. 3c, 3e, and 5a, which have been repeated in more than 3 independent experiments. Specifically, the “dancing crescents” in Fig. 5b and supplementary Fig. 4b were seen in all cells that expressed PH-GFP and responded directionally to cAMP gradient. Fig. 1c has been repeated 3 times. The dynamic flashes of PH-Akt-GFP in supplementary Fig. 5a were observed in over 10 experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank A. Kortholt and P. Van Haastert (University of Groningen) for the RBD-GFP construct as well as sGC– and sGC–/plaA–/piaA– cells, R. Kay (MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, UK) for AX2 cells, Gerisch (Max Planck Institute for Biochemistry, Germany) for the LimE-RFP construct, M. Ueda (Osaka University) for the Gα2-Cerulean and Gβ-Venus constructs, C. Cooper (Johns Hopkins University) for FUW lentivirus packaging system and members of the Devreotes and Iglesias labs for helpful suggestions. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, GM28007 (to P.N.D.), GM34933 (to P.N.D.), and GM71920 (to P.A.I.), and a Harold L. Plotnick Fellowship from the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, DRG2019-09 (to C.H.H.).

Footnotes

Author contributions

M.T., C-H.H. and M.W. performed the experiments. C.S. and P.A.I. carried out computer simulations. All authors analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. C-H.H. and P.N.D. supervised the study.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Swaney KF, Huang CH, Devreotes PN. Eukaryotic chemotaxis: a network of signaling pathways controls motility, directional sensing, and polarity. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:265–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iglesias PA, Devreotes PN. Navigating through models of chemotaxis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zigmond SH. Mechanisms of sensing chemical gradients by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Nature. 1974;249:450–452. doi: 10.1038/249450a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mato JM, Losada A, Nanjundiah V, Konijn TM. Signal input for a chemotactic response in the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:4991–4993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.12.4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tranquillo RT, Lauffenburger DA, Zigmond SH. A stochastic model for leukocyte random motility and chemotaxis based on receptor binding fluctuations. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:303–309. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller D, et al. External and internal constraints on eukaryotic chemotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9656–9659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911178107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hecht I, Kessler DA, Levine H. Transient localized patterns in noise-driven reaction-diffusion systems. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;104:158301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.158301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitelam S, Bretschneider T, Burroughs NJ. Transformation from spots to waves in a model of actin pattern formation. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;102:198103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.198103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlsson AE. Dendritic actin filament nucleation causes traveling waves and patches. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;104:228102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.228102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arrieumerlou C, Meyer T. A local coupling model and compass parameter for eukaryotic chemotaxis. Dev Cell. 2005;8:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parent CA, Devreotes PN. A cell's sense of direction. Science. 1999;284:765–770. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levchenko A, Iglesias PA. Models of eukaryotic gradient sensing: application to chemotaxis of amoebae and neutrophils. Biophys J. 2002;82:50–63. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75373-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levine H, Kessler DA, Rappel WJ. Directional sensing in eukaryotic chemotaxis: a balanced inactivation model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9761–9766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601302103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeda K, et al. Incoherent feedforward control governs adaptation of activated ras in a eukaryotic chemotaxis pathway. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra2. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang Y, Othmer HG. A G protein-based model of adaptation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Math Biosci. 1994;120:25–76. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong K, Pertz O, Hahn K, Bourne H. Neutrophil polarization: spatiotemporal dynamics of RhoA activity support a self-organizing mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3639–3644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600092103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onsum M, Rao CV. A mathematical model for neutrophil gradient sensing and polarization. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e36. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue T, Meyer T. Synthetic activation of endogenous PI3K and Rac identifies an AND-gate switch for cell polarization and migration. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houk AR, et al. Membrane Tension Maintains Cell Polarity by Confining Signals to the Leading Edge during Neutrophil Migration. Cell. 2012;148:175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen L, et al. Two phases of actin polymerization display different dependencies on PI(3,4,5)P3 accumulation and have unique roles during chemotaxis. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:5028–5037. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerisch G, Malchow D, Roos W, Wick U. Oscillations of cyclic nucleotide concentrations in relation to the excitability of Dictyostelium cells. J Exp Biol. 1979;81:33–47. doi: 10.1242/jeb.81.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerisch G, Hess B. Cyclic-AMP-controlled oscillations in suspended Dictyostelium cells: their relation to morphogenetic cell interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:2118–2122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.5.2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Postma M, et al. Uniform cAMP stimulation of Dictyostelium cells induces localized patches of signal transduction and pseudopodia. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:5019–5027. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lappano S, Coukell MB. Evidence that intracellular cGMP is involved in regulating the extracellular cAMP phosphodiesterase and its specific inhibitor in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev Biol. 1982;93:43–53. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Futrelle RP, Traut J, McKee WG. Cell behavior in Dictyostelium discoideum: preaggregation response to localized cyclic AMP pulses. J Cell Biol. 1982;92:807–821. doi: 10.1083/jcb.92.3.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meinhardt H. Orientation of chemotactic cells and growth cones: models and mechanisms. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 17):2867–2874. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.17.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiong Y, Huang CH, Iglesias PA, Devreotes PN. Cells navigate with a local-excitation, global-inhibition-biased excitable network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17079–17086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011271107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neilson MP, et al. Chemotaxis: a feedback-based computational model robustly predicts multiple aspects of real cell behaviour. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishikawa M, Horning M, Ueda M, Shibata T. Excitable signal transduction induces both spontaneous and directional cell asymmetries in the phosphatidylinositol lipid signaling system for eukaryotic chemotaxis. Biophys J. 2014;106:723–734. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shibata T, Nishikawa M, Matsuoka S, Ueda M. Intracellular encoding of spatiotemporal guidance cues in a self-organizing signaling system for chemotaxis in dictyostelium cells. Biophys J. 2013;105:2199–2209. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang CH, Tang M, Shi C, Iglesias PA, Devreotes PN. An excitable signal integrator couples to an idling cytoskeletal oscillator to drive cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1307–1316. doi: 10.1038/ncb2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charest PG, et al. A Ras signaling complex controls the RasC-TORC2 pathway and directed cell migration. Dev Cell. 2010;18:737–749. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kortholt A, King JS, Keizer-Gunnink I, Harwood AJ, Van Haastert PJ. Phospholipase C regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated chemotaxis. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4772–4779. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kortholt A, et al. Dictyostelium chemotaxis: essential Ras activation and accessory signalling pathways for amplification. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:1273–1279. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hecht I, et al. Activated membrane patches guide chemotactic cell motility. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper RM, Wingreen NS, Cox EC. An excitable cortex and memory model successfully predicts new pseudopod dynamics. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bretschneider T, et al. Dynamic actin patterns and Arp2/3 assembly at the substrate-attached surface of motile cells. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi C. Study of eukaryotic cellular process by mathematical modeling: Chemotaxis and mitosis. Dissertation. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma W, Trusina A, El-Samad H, Lim WA, Tang C. Defining network topologies that can achieve biochemical adaptation. Cell. 2009;138:760–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janetopoulos C, Jin T, Devreotes P. Receptor-mediated activation of heterotrimeric G-proteins in living cells. Science. 2001;291:2408–2411. doi: 10.1126/science.1055835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iglesias PA, Devreotes PN. Biased excitable networks: how cells direct motion in response to gradients. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vicker MG. Eukaryotic cell locomotion depends on the propagation of self-organized reaction-diffusion waves and oscillations of actin filament assembly. Exp Cell Res. 2002;275:54–66. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiner OD, Marganski WA, Wu LF, Altschuler SJ, Kirschner MW. An actin-based wave generator organizes cell motility. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerisch G, et al. Mobile actin clusters and traveling waves in cells recovering from actin depolymerization. Biophys J. 2004;87:3493–3503. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arai Y, et al. Self-organization of the phosphatidylinositol lipids signaling system for random cell migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12399–12404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908278107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bretschneider T, et al. The three-dimensional dynamics of actin waves, a model of cytoskeletal self-organization. Biophys J. 2009;96:2888–2900. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asano Y, Nagasaki A, Uyeda TQ. Correlated waves of actin filaments and PIP3 in Dictyostelium cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2008;65:923–934. doi: 10.1002/cm.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi C, Huang CH, Devreotes PN, Iglesias PA. Interaction of motility, directional sensing, and polarity modules recreates the behaviors of chemotaxing cells. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e1003122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Veltman DM, Keizer-Gunnik I, Van Haastert PJ. Four key signaling pathways mediating chemotaxis in Dictyostelium discoideum. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:747–753. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoeller O, Kay RR. Chemotaxis in the absence of PIP3 gradients. Curr Biol. 2007;17:813–817. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Srinivasan K, et al. Delineating the core regulatory elements crucial for directed cell migration by examining folic-acid-mediated responses. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:221–233. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veltman DM, Lemieux MG, Knecht DA, Insall RH. PIP3-dependent macropinocytosis is incompatible with chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:497–505. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201309081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iijima M, Devreotes P. Tumor suppressor PTEN mediates sensing of chemoattractant gradients. Cell. 2002;109:599–610. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00745-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins during receptor desensitization. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:9–18. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hadwiger JA, Lee S, Firtel RA. The G alpha subunit G alpha 4 couples to pterin receptors and identifies a signaling pathway that is essential for multicellular development in Dictyostelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10566–10570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumagai A, Hadwiger JA, Pupillo M, Firtel RA. Molecular genetic analysis of two G alpha protein subunits in Dictyostelium. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1220–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liao XH, Buggey J, Lee YK, Kimmel AR. Chemoattractant stimulation of TORC2 is regulated by receptor/G protein-targeted inhibitory mechanisms that function upstream and independently of an essential GEF/Ras activation pathway in Dictyostelium. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:2146–2155. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-03-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cai H, Huang CH, Devreotes PN, Iijima M. Analysis of chemotaxis in dictyostelium. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;757:451–468. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-166-6_26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng GE, Wilson SR, Weiner OD. A pharmacological cocktail for arresting actin dynamics in living cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:3986–3994. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-04-0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Postma M, Van Haastert PJ. A diffusion-translocation model for gradient sensing by chemotactic cells. Biophys J. 2001;81:1314–1323. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75788-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pitt GS, et al. Structurally distinct and stage-specific adenylyl cyclase genes play different roles in Dictyostelium development. Cell. 1992;69:305–315. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu L, Valkema R, Van Haastert PJ, Devreotes PN. The G protein beta subunit is essential for multiple responses to chemoattractants in Dictyostelium. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1667–1675. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kamimura Y, et al. PIP3-independent activation of TorC2 and PKB at the cell's leading edge mediates chemotaxis. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1034–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.