Bacterial meningitis is typically diagnosed with a lumbar puncture, which usually reveals an elevated opening pressure and high white blood cell count. In this article, the authors report a case involving an 83-year-old woman who had normal cerebrospinal fluid findings on presentation, but who was subsequently found to have meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitidis. The authors discuss potential reasons for normal cerebrospinal fluid findings in the context of meningitis.

Keywords: Bacterial meningitis, Lumbar puncture, Meningococcal meningitis, Neisseria meningitidis, Normal cerebrospinal fluid

Abstract

Elevation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cell count is a key sign in the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis. However, there have been reports of bacterial meningitis with no abnormalities in initial CSF testing. This type of presentation is extremely rare in adult patients. Here, a case involving an 83-year-old woman who was later diagnosed with bacterial meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitidis is described, in whom CSF at initial and second lumbar puncture did not show elevation of cell counts. Twenty-six non-neutropenic adult cases of bacterial meningitis in the absence of CSF pleocytosis were reviewed. The frequent causative organisms were Streptococcus pneumoniae and N meningitidis. Nineteen cases had bacteremia and seven died. The authors conclude that normal CSF at lumbar puncture at an early stage cannot rule out bacterial meningitis. Therefore, repeat CSF analysis should be considered, and antimicrobial therapy must be started immediately if there are any signs of sepsis or meningitis.

Abstract

L’élévation de la numération des cellules du liquide céphalorachidien (LCR) est un signe clé pour diagnostiquer la méningite bactérienne. Cependant, il existe des cas de méningite bactérienne sans anomalie initiale du LCR. Ce type de présentation est d’une extrême rareté chez les patients adultes. Le présent rapport décrit le cas d’une femme de 83 ans qui a ensuite obtenu un diagnostic de méningite bactérienne causée par le Neisseria meningitidis, chez qui le LCR, lors des deux premières ponctions lombaires, n’a démontré aucune élévation de la numération cellulaire. Les chercheurs ont analysé 26 cas d’adultes non neutropéniques atteints de méningite bactérienne sans pléïocytose du LCR. Le Streptococcus pneumoniae et le N meningitidis en étaient souvent les organismes responsables. Dix-neuf cas présentaient une bactériémie et sept sont décédés. Les auteurs ont conclu qu’au début de la maladie, un LCR normal à la ponction lombaire ne permet pas d’écarter la possibilité de méningite bactérienne. Ainsi, il faut envisager de reprendre l’analyse du LCR et amorcer le traitement anti-microbien immédiatement en cas de signe de sepsis ou de méningite.

Bacterial meningitis is a lethal disease that requires immediate antimicrobial therapy (1). Lumbar puncture is a key diagnostic procedure and elevation of cell counts in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is an important sign of bacterial meningitis (2). We present an uncommon case of bacterial meningitis in which initial CSF analysis showed neither cell elevation nor culture growth, but later showed growth of Neisseria meningitidis.

CASE PRESENTATION

The patient was an 83-year-old woman with a history of diabetes and hypertension. She was brought to the emergency department by her family. On the day of admission, she developed fever with chills and became slightly disoriented.

She was taking sulfonylurea and a calcium channel blocker. There was no history taking ill contacts. She was alert but slightly disoriented. Her vital signs were blood pressure 165/85 mmHg, heart rate 86 beats/min, body temperature 39.0°C, respiratory rate 20 breaths/min and oxygen saturation on room air 90%. Physical examination revealed no stiff neck and no crackles, but slight tenderness on both thighs. Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis (11.0×109/L; normal range <9.8×109/L) and elevated C-reactive protein level (34.6 mg/L; normal range <4.0 mg/L). Hemoglobin, platelets, serum electrolyte and plasma glucose levels, liver function tests and creatine phosphokinase level were all normal. Urinalysis revealed neither bacteriuria nor pyuria. A chest x-ray did not show any signs of pneumonia. A computed tomography scan with contrast did not identify any source of fever. A lumbar puncture was also performed in the emergency department. Her CSF was clear and colourless. Initial pressure was 170 mmH2O. The CSF cell count was 2×106 cells/L without red blood cells, glucose level was 5.16 mmol/L (plasma glucose level 8.32 mmol/L) and protein level was 0.56 g/L; no organisms were observed on Gram stain. Rapid flu antigen testing (BD EZ Flu A+B Test, Becton Dickinson, Japan) was negative. Two sets of blood cultures were obtained. She was admitted by the general internal medicine team and followed up with close monitoring.

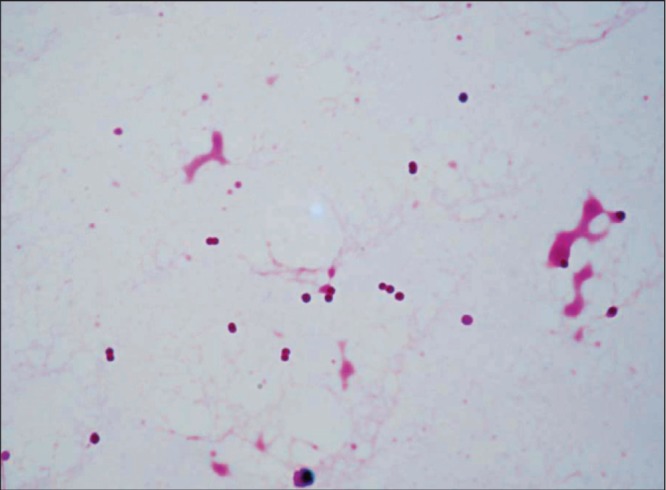

The next morning, Gram-negative diplococci were detected in both sets of blood cultures using BD BACTEC (Becton Dickinson, Japan). N meningitidis was suspected and ceftriaxone was administered immediately. A lumbar puncture was repeated 18 h after the first lumbar puncture. Her CSF was clear and colourless, and the initial pressure was 160 mmH2O. The CSF cell count was 1×106 cells/L without red blood cells, glucose level 4.38 mmol/L (plasma glucose 12.88 mmol/L) and protein level 0.53 g/L. Gram staining of CSF showed Gram-negative diplococci (Figure 1). On the same day, she experienced a seizure of the right extremities. Diazepam was given to stop the seizure.

Figure 1).

Cerebrospinal fluid from second lumbar puncture showing Gram-negative cocci

On admission day 3, she complained of right knee pain and her knee was swollen. Arthrocentesis was performed and Gram staining of joint fluid showed Gram-negative diplococci. On admission day 4, the results of both blood and CSF cultures were identified as N meningitidis by MicroScan WalkAway (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Japan). Culture of joint fluid later also revealed N meningitidis. Ceftriaxone was discontinued and the patient was started on penicillin G according to susceptibility test results. Administration of penicillin G and drainage of the knee joint were continued for three weeks, and all of her symptoms disappeared during the treatment. She was eventually discharged after rehabilitation.

The patient was confirmed to be negative for anti-HIV antibody, complement was normal and she did not have a history of splenectomy. As postexposure prophylaxis, ciprofloxacin was prescribed for five medical staff and three family members who had come into close contact with the patient, none of whom later developed meningococcal infection.

DISCUSSION

A diagnosis of bacterial meningitis is made based on clinical symptoms and analysis of CSF. Because it takes time for CSF culture to confirm the diagnosis, treatment should be started immediately if the cytological profile of CSF suggests bacterial meningitis, which typically shows elevated opening pressure (200 mmH2O to 500 mmH2O), pleocytosis (1000×106 to 5000×106 white blood cells/L) with a predominance of neutrophils (≥80%), elevated protein levels (1.00 g/L to 5.00 g/L) and decreased CSF-to-serum glucose ratio (≤0.4) (1,3). Brouwer et al (4) reported that >90% of cases of acute bacterial meningitis presented with a CSF white blood cell count >100×106 cells/L, and an acellular CSF is rare except in patients with tuberculous meningitis. However, our patient exhibited a normal cell count in the CSF.

Pediatric cases of bacterial meningitis without initial CSF findings have been reported. Polk and Steele (5) reported that seven of 261 pediatric meningitis patients had a positive CSF culture without any abnormalities on initial CSF tests. They estimated that pediatric meningitis without pleocytosis accounts for 0.5% to 12% of all cases of bacterial meningitis.

On the other hand, cases of bacterial meningitis without initial CSF pleocytosis in adults have rarely been reported. Only 26 cases, including the present case, were found in a search of English abstracts in the MEDLINE database. Patients with documented neutropenia were excluded (Table 1) (6–20). Of these, 11 cases had Streptococcus pneumoniae, 10 had N meningitidis, two had Escherichia coli, one had Proteus mirabilis, one had Listeria monocytogenes and one had Haemophilus influenzae. Blood culture was performed in 24 cases and bacteremia was detected in 19. The outcome was documented in 20 cases. Seven patients died and two exhibited auditory disorders. The timing of antimicrobial therapy was analyzed in 18 patients. Empirical treatment had not been implemented in five patients.

TABLE 1.

Summary of 26 non-neutropenic cases of bacterial meningitis without pleocytosis reported in English and the present case

| Case | Age, years, sex | Causative organism | CSF cell count (×106/L); upper: first, lower: second | CSF protein, g/L | CSF-to-serum glucose ratio* CSF/serum, mmol/L | Gram stain | CSF culture | Blood culture | Empirical treatment | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 47 | Neisseria meningitidis | 0 | 0.45 | 7.05/NA | Negative | Positive | Negative | NA | NA | 6 |

| 2 | 30 M | N meningitidis | 0 | 0.47 | 0.74 | Negative | Negative | Positive | NA | Death | 7 |

| 90 | 1.73 | 0.51 | Positive | Positive | |||||||

| 3 | 76 F | Proteus mirabilis | 0 | 0.58 | 0.63 | Negative | Positive | Positive | Yes | Death | |

| 2220 | 7.55 | 0/NA | Positive | Positive | |||||||

| 4 | 67 M | N meningitidis | 2 | 1.19 | 0.42 | Negative | Positive | Positive | Yes | Survived | |

| 70 | 2.65 | 6.49/NA | Positive | Negative | |||||||

| 5 | 54 F | Escherichia coli | 0 | 0.49 | 0.54 | Negative | Positive | Positive | Yes | Death | 8 |

| 4 | 1.84 | 0.4 | Positive | NA | |||||||

| 6 | 57 M | Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 | 0.97 | 0.65 | Negative | Positive | Positive | Yes | Survived | |

| 7 | 86 M | S pneumoniae | 0 | 0.40 | 0.60 | Positive | Positive | Positive | Yes | Death | |

| 8 | 52 M | E coli | 6 | 0.55 | 0.57 | Negative | Positive | Positive | No | Death | |

| 9 | 50 F | S pneumoniae | 0 | 0.21 | 0.54 | Negative | Positive | Positive | Yes | Survived | 9 |

| 393 | 0.76 | 0.36 | Negative | Negative | |||||||

| 10 | 26 M | Haemophilus influenzae | 1 | 0.32 | 3.94/NA | Negative | Negative | Positive | No | Survived | 10 |

| 16,600 | 11.00 | 2.72/NA | NA | Positive | |||||||

| 11 | 59 F | N meningitidis | 1 | 0.36 | 0.8 | NA | Positive | Positive | NA | NA | 11 |

| 12 | 50 F | S pneumoniae | 0 | 021 | 0.54 | NA | Positive | Positive | NA | NA | |

| 13 | 40 F | N meningitidis | 0 | 0.32 | 0.85 | NA | Positive | Negative | NA | NA | |

| 14 | 23 F | N meningitidis | 0 | 0.27 | 0.69 | NA | Positive | Positive | NA | NA | |

| 15 | 33 F | Listeria monocytogenes | 0 | 0.10 | 0.71 | NA | Positive | Positive | NA | NA | |

| 16 | 69 M | N meningitidis | 3 | 0.40 | 3.89/NA | NA | Positive | Positive | NA | Survived | 12 |

| 17 | 18 M | S pneumoniae | 0 | 3.00 | 0.22/5.00–7.21 | Positive | Positive | NA | Yes | Death | 13 |

| 18 | 52 M | S pneumoniae | 6 | 0.26 | 3.94/NA | Negative | Positive | Positive | Yes | Survived | 14 |

| 2709 | 3.60 | 0.72/NA | Positive | Positive | |||||||

| 19 | 74 F | S pneumoniae | 1 | 0.54 | 0.85 | NA | Positive | Negative | Yes | Survived | 15 |

| 20 | 24 F | N meningitidis | 2 | 0.20 | 0.70 | Positive | Positive | Positive | Yes | Survived | 16 |

| 5600 | 3.00 | 0.72/NA | Negative | Negative | |||||||

| 21 | 21 F | N meningitidis | 1 | 0.38 | 3.61/NA | Negative | Positive | Positive | Yes | Survived | 17 |

| 22 | 60 F | S pneumoniae | 1 | 0.39 | 0.64 | Negative | Negative | Positive | No | Survived | 18 |

| 63 | 0.74 | 0.72 | Negative | Positive | |||||||

| 23 | 37 M | S pneumoniae | 1 | 0.47 | 2.89/NA | Negative | Positive | Negative | Yes | Survived | 19 |

| 24 | 34 F | S pneumoniae | 2 | 0.40 | 0.61 | Positive | Positive | Negative | Yes | Survived | 20 |

| 4086 | 2.70 | 0.10 | Not done | NA | |||||||

| 25 | 62 M | S pneumoniae | 1 | 1.25 | 0.12 | Positive | Positive | Not performed | No | Death | |

| 26 | 83 F | N meningitidis | 2 | 0.56 | 0.62 | Negative | Negative | Positive | No | Survived | Present case |

| 1 | 0.53 | 0.34 | Positive | Positive |

Either cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or serum glucose is shown where the ratio cannot be calculated. F Female; M Male; NA Not available

Neutropenia is known to be associated with no response in CSF (11). Lukes et al (21) reported that 45% of neutropenic patients with bacterial central nervous system infection did not have pleocytosis. Fishbein et al (8) also reported two other patients with neutropenia caused by bacterial meningitis with normal CSF cell counts. Therefore, we excluded patients with neutropenia from the literature review.

Factors such as age and congenital or acquired immune deficiencies in host defense mechanisms other than neutropenia may be responsible for the absence of an inflammatory response in initial CSF analysis. Five patients (cases 5 to 8, 24) without pleocytosis were elderly, severely alcoholic or had a history of splenectomy. However, many of the other patients, including our patient (case 26), were not severely immunocompromised.

Another possible explanation is that the organism contaminated the CSF from bacteremic blood by lumbar puncture. This hypothesis is based on the report that cisternal puncture in dogs with S pneumoniae bacteremia results in meningitis provided there are at least 103 organisms per milliliter of blood (22). However, there is a lack of data supporting this etiology in humans. Lumbar puncture was performed gently and no blood contamination was observed in our patient. A traumatic tap was not documented for most of the patients on the list and, therefore, it appears to be unlikely that the initial lumbar puncture caused the meningitis in this case.

Our case suggested that lumbar puncture was performed in the early stage, when no inflammatory reaction had occurred in the patient. The organism grew from the second CSF sample, although none grew from the first CSF sample. The same phenomenon was observed in case 2, case 10 and case 22. These CSF results showed the transitional process of developing meningitis from bacteremia.

SUMMARY

We encountered a case of bacterial meningitis with N meningitidis in which CSF at the early stage did not show pleocytosis. Only 26 nonneutropenic adult cases, including our case, have been reported with this unique presentation. Normal CSF does not always rule out bacterial meningitis and, therefore, repeat CSF analysis should be considered and antimicrobial therapy must be started immediately if there are any signs of sepsis or meningitis.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1267–84. doi: 10.1086/425368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spanos A, Harrell FE, Jr, Durack DT. Differential diagnosis of acute meningitis. An analysis of the predictive value of initial observations. JAMA. 1989;262:2700–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, Mandell Douglas. Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th edn. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouwer MC, Thwaites GE, Tunkel AR, van de Beek D. Dilemmas in the diagnosis of acute community-acquired bacterial meningitis. Lancet. 2012;380:1684–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polk DB, Steele RW. Bacterial meningitis presenting with normal cerebrospinal fluid. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:1040–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fimlt AM, Hamilton W. Developing or normocellular bacterial meningitis. N Z Med J. 1976;84:6–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onorato IM, Wormser GP, Nicholas P. ‘Normal’ CSF in bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 1980;244:1469–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fishbein DB, Palmer DL, Porter KM, Reed WP. Bacterial meningitis in the absence of CSF pleocytosis. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:1369–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ris J, Mancebo J, Domingo P, Cadafalch J, Sanchez JM. Bacterial meningitis despite normal CSF findings. JAMA. 1985;254:2893–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bamberger DM, Smith OJ. Haemophilus influenzae meningitis in an adult with initially normal cerebrospinal fluid. South Med J. 1990;83:348–9. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199003000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domingo P, Mancebo J, Blanch L, Coll P, Net A, Nolla J. Bacterial meningitis with “normal” cerebrospinal fluid in adults: A report on five cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 1990;22:115–6. doi: 10.3109/00365549009023130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coll MT, Uriz MS, Pineda V, et al. Meningococcal meningitis with ‘normal’ cerebrospinal fluid. J Infect. 1994;29:289–94. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(94)91197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zenebe G. Adult pneumococcal meningitis with no inflammatory cells in the CSF. Ethiop Med J. 1994;32:265–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchihara T, Ichikawa K, Yoshida S, Tsukagoshi H. Positive culture from normal CSF of Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis. Eur Neurol. 1996;36:234. doi: 10.1159/000117256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutierrez-Macias A, Garcia-Jimenez N, Sanchez-Munoz L, Martinez-Ortiz de Zarate M. Pneumococcal meningitis with normal cerebrospinal fluid in an immunocompetent adult. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:219. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(99)90074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rebeu-Dartiguelongue I, Laurent JP, Clarac A, et al. [Early lumbar puncture and cutaneous rash: A clear CSF is not always a normal CSF] Med Mal Infect. 2005;35:422–4. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huynh W, Lahoria R, Beran RG, Cordato D. Meningococcal meningitis and a negative cerebrospinal fluid: Case report and its medicolegal implications. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:553–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montassier E, Trewick D, Batard E, Potel G. Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis in an adult with normal cerebrospinal fluid. CMAJ. 2011;183:1618–20. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alvarez EF, Olarte KE, Ramesh MS. Purpura fulminans secondary to Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2012;2012:508503. doi: 10.1155/2012/508503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki H, Tokuda Y, Kurihara Y, Suzuki M, Nakamura H. Adult pneumococcal meningitis presenting with normocellular cerebrospinal fluid: Two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:294. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukes SA, Posner JB, Nielsen S, Armstrong D. Bacterial infections of the CNS in neutropenic patients. Neurology. 1984;34:269–75. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersdorf RG, Swarner DR, Garcia M. Studies on the pathogenesis of meningitis. II. Development of meningitis during pneumococcal bacteremia. J Clin Invest. 1962;41:320–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI104485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]