Proper functioning of the mammalian central nervous system (CNS) depends on the spatially and temporally regulated generation of neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes (1, 2). In rodents, virtually all neurogenesis occurs prenatally, except in two specific areas of the brain that continue to give rise to new neurons throughout life: the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the forebrain and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampus (3). Most gliogenesis occurs in the perinatal or early postnatal period. Disturbance of the sequential generation rule of “neurons first, followed by glia” has been postulated to cause not only cytoarchitectural defects in the cerebral cortex, but also CNS dysfunction (4, 5). Ke et al. (6) and Gauthier et al. (7) recently demonstrated the importance of the relative timing of neurogenesis and gliogenesis by examining the role of a tyrosine phosphatase, SHP2, during development.

Sequential Generation of Neurons and Glia from Neural Stem Cells

Neural stem and progenitor cells (NPCs) have the potential to generate both neurons and glia. In vitro experiments have shown that NPCs from the developing cerebral cortex, or NPCs derived from pluripotent embryonic stem cells, retain the timing information required for the temporally appropriate generation of neurons and glia in culture (4). Short-term culture (less than 4 days in vitro) of NPCs isolated from relatively early embryonic stages, such as mouse embryonic day 10 to 11 (E10 to E11), predominantly yields neurons, whereas cortical progenitors isolated from perinatal stages predominantly produce astrocytes under the same culture conditions (5). Furthermore, when cultured for longer periods of time, E10 to E11 NPCs switch from a “neurogenic” to a “gliogenic” mode, producing astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (4). This suggests that the mechanism controlling the transition of NPCs from a neurogenic to a gliogenic phase may be programmed into the NPC.

Gain- and loss-of-function studies have revealed two opposing pathways in the developing CNS that promote neurogenesis or gliogenesis, respectively: (i) the proneural basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) gene-mediated neurogenic pathway and (ii) the JAK-STAT (Janus kinase–signal transducers and activators of gene transcription)–mediated gliogenic pathway (5, 8–10). Proneural bHLH genes are highly expressed in early (neurogenic) NPCs, in which the JAK-STAT pathway is substantially suppressed (5). Under these conditions, only neuronal differentiation takes place. However, in later gliogenic NPCs, the JAK-STAT pathway can be robustly activated, thereby initiating astrocytic differentiation (5). It thus appears that the balance between proneural bHLH gene-mediated transcription and STAT1 and 3 (STAT1/3)–mediated transcription determines the outcome of NPC lineage differentiation.

Regulation of NPC Differentiation by Environmental Factors

It is plausible that the timing of neurogenesis and gliogenesis during development is controlled by both cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic factors. Growth factors [such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)], the interleukin-6 (IL-6) family of cytokines [including leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), and cardiotrophin-1], and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and Wnts play important roles in the development of the CNS (8, 10–21). The effects of extracellular factors on NPCs are often pleiotropic and depend on the intracellular context (4, 8). Signal transduction pathways that convey the effects of extracellular factors to the transcriptional machinery are intimately tied to the decision to initiate neurogenesis or gliogenesis.

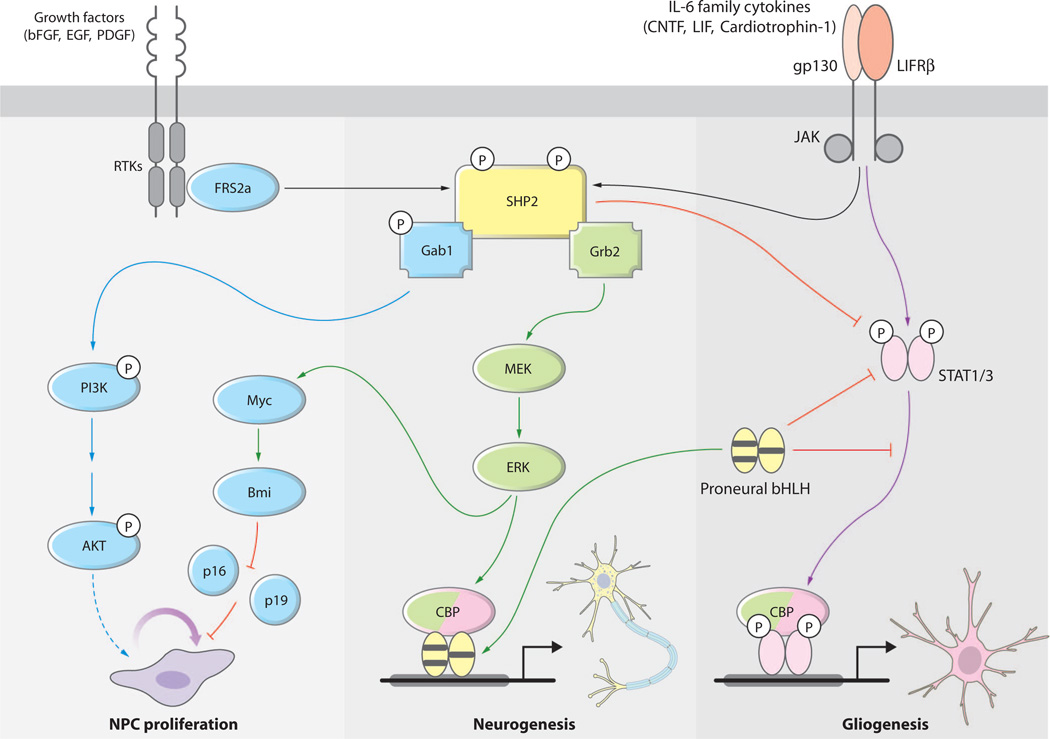

Two major signaling cascades work together during development to regulate the temporally appropriate generation of neurons and glia (Fig. 1). MEK-ERK (mitogen-activated or extracellular signal–regulated protein kinase kinase and its target extracellular signal–regulated protein kinase) signaling promotes generation of neurons in the developing telencephalon (22). Proneural genes can activate the neurogenesis pathway even when the MEK-ERK pathway is inhibited. However, the MEK-ERK pathway does seem to be able to potentiate the neurogenic function of proneural genes to a certain extent. Gliogenesis, by contrast, requires activation of the JAK-STAT pathway by cytokines acting through the gp130 receptor (10). One reason that neurogenesis always precedes gliogenesis relates to the dynamic regulation of the overall activity of JAK-STAT signaling in vivo (5, 23). Specifically, STAT1/3 activation and STAT-mediated transcription are suppressed at early (neurogenic) periods by epigenetic factors, such as DNA methylation, as well as by the expression of the proneural bHLH transcription factors neurogenin-1 and -2 (Ngn1/2) (5, 24, 25). Neurogenins repress astrocytic fate by inhibiting STAT phosphorylation and sequestering the CBP/p300 [the transcriptional coactivators cAMP response element–binding protein (CREB)-binding protein (CBP) and p130]–Smad1 complex away from STATs to block their activity on genes that promote astroglial differentiation (8).

Fig. 1.

The tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 is required for the proper timing of neurogenesis and gliogenesis and the balance between them during CNS development. SHP2 enhances neurogenesis through the growth factor–receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)–activated MEK-ERK pathway (green arrows) together with proneural bHLH factors. SHP2 also prevents early onset of gliogenesis by inhibiting the CNTF-, LIF-gp130–, and LIFRβ-activated JAK-STAT pathway (purple arrows) during the neurogenic period. Moreover, SHP2 is required for maintaining NPC proliferation through other signaling pathways such as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT pathway (blue arrows), as well as ERK-Myc-Bmi–mediated pathways.

SHP2 Enhances Neurogenesis and Inhibits Gliogenesis

Ke et al. and Gauthier et al. examined the role of SHP2 during the proliferation and differentiation of embryonic NPCs in the telencephalon. SHP2 is an appealing molecule in the context of regulation of neurogenesis and gliogenesis, because it modulates not only the neurogenic (MEK-ERK), but also the gliogenic (gp130–JAK-STAT) signaling pathways by promoting MEK-ERK signaling while simultaneously inhibiting gp130–JAK-STAT signaling, respectively (6, 7, 26) (Fig. 1). Both studies—primarily using loss-of-function approaches— indicated that SHP2 positively regulates neurogenesis and inhibits gliogenesis in vitro and in vivo.

Ke et al. created a novel conditional knockout mouse model, in which SHP2 is selectively deleted in Nestin-positive NPCs. Nestin is an intermediate filament, which is widely used as a marker to label NPCs. The mutant animals displayed early postnatal lethality. A closer examination of SHP2-deficient brains, with markers specific for particular cortical layers, showed lamination defects in the cerebral cortex. More importantly, Ke et al. observed that in SHP2-deficient animals, there was a reduced number of cells positive for the neuronal marker TuJ1 and an increased number of cells positive for the astrocytic marker GFAP (glial f ibrillary acidic protein). Using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) directed against SHP2 in uterine electroporation approaches to knockdown SHP2 in embryos, Gauthier et al. independently reached the same conclusion. Thus, findings from both studies point to a pivotal role of SHP2 in the positive regulation of neurogenesis and negative regulation of gliogenesis.

Involvement of SHP2 in the Proliferation of NPCs

Ke et al. also found that SHP2 deficiency resulted in decreased proliferation of NPCs in the developing cerebral cortex. Further analyses by Ke et al. with in vitro neural stem cell assays showed that SHP2 deficiency led to decreased formation of neurospheres (free-floating cellular masses clonally generated by a single progenitor or stem cell) by NPCs isolated from E14.5 mouse brains. Moreover, SHP2-deficient cells showed decreased ERK1/2 phosphorylation, as well as increased STAT3 phosphorylation, which is consistent with reduced neurogenesis and increased gliogenesis in SHP2-deficient neurospheres. To determine the upstream cell-proliferation triggers that act through SHP2, Ke et al. demonstrated that, in SHP2-deficient cells, bFGF-induced MEK-ERK activation is abolished. They postulated that a bFGF–SHP2–ERK–c-Myc–Bmi-1 signaling cascade is essential for the proliferation of NPCs. The role of Bmi-1, a polycomb group repressor, has been documented in the self-renewal of hematopoietic and neuronal stem cells (27, 28). It remains to be determined whether SHP2 primarily promotes proliferation of lineage-restricted NPCs (neuroblasts), multipotent NPCs, or both. Given that SHP2 promotes both neurogenesis and NPC proliferation, it is possible that, similar to the effect of PDGF, SHP2 enhances the proliferation of neuroblasts and subsequently increases the number of terminally differentiated neurons (21). In contrast, Gauthier et al. suggested that the effect of SHP2 was “restricted” to differentiating cells of the developing telencephalon, which do not proliferate. Using shRNA in combination with in uterine electroporation, Gauthier et al. concluded that SHP2, while promoting neurogenesis and inhibiting cytokine-mediated astrogliogenesis, was not essential for either the proliferation or survival of cortical NPCs. It is conceivable that the transient knockdown of SHP2 by shRNA approach used by Gauthier et al. may have missed a possible “long-term” effect of SHP2 deficiency on NPC proliferation. Moreover, Gauthier et al. found that an enzymatically inactive form of SHP2 failed to inhibit astrogliogenesis, whereas it still promoted neurogenesis, suggesting that the regulation of neurogenesis by SHP2 was independent of its phosphatase activity.

Association of SHP2 with Noonan Syndrome

SHP2 has been implicated in Noonan syndrome (NS), which is manifested by delayed puberty, hearing loss, mild mental retardation (in about 25% of cases), ptosis, short stature, and unusual chest shape (pectus excavatum) in 1 in 1000 to 2500 children (29–31). In half of NS cases, a missense mutation results in an increase in the phosphatase activity of SHP2. One such example is the D61G-SHP2 mutation (in which aspartic acid at position 61 is substituted with glycine), which is observed in 10% of NS patients. Gauthier et al. demonstrated that the D61G-SHP2 mutation enhanced neurogenesis and reduced gliogenesis both in vitro and in vivo. Although these experiments examined the involvement of SHP2 in NS, they used overexpression of SHP2, whereas in NS, only one copy of the gene carries the mutation. To better simulate the NS condition, Gauthier et al. examined a NS mouse model carrying only one copy of D61G-SHP2 knocked into the endogenous SHP2 locus. Analysis of the mutant mouse revealed a slight increase in the number of neurons and a substantial decrease in the number of GFAP-positive astrocytes in the hippocampus and dorsal cortex. This finding is somewhat contradictory to the data showing that the role of SHP2 in enhancing neurogenesis is independent of its phosphatase activity. Future studies are needed to resolve this discrepancy and to determine whether NS is primarily caused by an imbalance between neuronal and glial differentiation.

SHP2 and the Transition from Neurogenesis to Gliogenesis

The studies by Ke et al. and by Gauthier et al. underscore the involvement of SHP2 in brain development. SHP2 interacts with neurogenic (MEK-ERK), as well as gliogenic (gp130-JAK-STAT) signaling pathways, and modulates the generation of neurons and astrocytes. However, because SHP2 is present throughout development and interacts with the neurogenic and gliogenic pathways in a continuous manner, it may not be the determinant factor in the switch from neurogenesis to gliogenesis. The dynamic changes in the levels of cytokines and growth factors that act upon SHP2 during development play important roles in the timing of neurogenesis and gliogenesis. The emerging data suggest that the switch mechanism may have at least four components: (i) self-perpetuation (positive feedback) of the JAK-STAT pathway (5); (ii) decrease in the function and expression of bHLH transcription factors (5); (iii) DNA demethylation of gliogenic genes (24, 25); and (iv) increased secretion of cardiotrophin from differentiating neurons (negative feedback) (14). It is unequivocally the interaction of these factors that determines when neural NPCs transit from producing neurons to glia.

References

- 1.Qian X, Shen Q, Goderie SK, He W, Capela A, Davis AA, Temple S. Timing of CNS cell generation: A programmed sequence of neuron and glial cell production from isolated murine cortical stem cells. Neuron. 2000;28:69–80. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sauvageot CM, Stiles CD. Molecular mechanisms controlling cortical gliogenesis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2002;12:244–249. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Amour K, Gage FH. New tools for human developmental biology. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:381–382. doi: 10.1038/74429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun YE, Martinowich K, Ge W. Making and repairing the mammalian brain–signaling toward neurogenesis and gliogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003;14:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(03)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He F, Ge W, Martinowich K, Becker-Catania S, Coskun V, Zhu W, Wu H, Castro D, Guillemot F, Fan G, de Vellis J, Sun YE. A positive autoregulatory loop of Jak-STAT signaling controls the onset of astrogliogenesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:616–625. doi: 10.1038/nn1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ke Y, Zhang EE, Hagihara K, Wu D, Pang Y, Klein R, Curran T, Ranscht B, Feng GS. Deletion of Shp2 in the brain leads to defective proliferation and differentiation in neural stem cells and early postnatal lethality. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:6706–6717. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01225-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gauthier AS, Furstoss O, Araki T, Chan R, Neel BG, Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Control of CNS cell-fate decisions by SHP-2 and its dysregulation in Noonan syndrome. Neuron. 2007;54:245–262. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y, Nadal-Vicens M, Misono S, Lin MZ, Zubiaga A, Hua X, Fan G, Greenberg ME. Neurogenin promotes neurogenesis and inhibits glial differentiation by independent mechanisms. Cell. 2001;104:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nieto M, Schuurmans C, Britz O, Guillemot F. Neural bHLH genes control the neuronal versus glial fate decision in cortical progenitors. Neuron. 2001;29:401–413. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonni A, Sun Y, Nadal-Vicens M, Bhatt A, Frank DA, Rozovsky I, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD, Greenberg ME. Regulation of gliogenesis in the central nervous system by the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Science. 1997;278:477–483. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qian X, Davis AA, Goderie SK, Temple S. FGF2 concentration regulates the generation of neurons and glia from multipotent cortical stem cells. Neuron. 1997;18:81–93. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viti J, Feathers A, Phillips J, Lillien L. Epidermal growth factor receptors control competence to interpret leukemia inhibitory factor as an astrocyte inducer in developing cortex. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3385–3393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03385.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johe KK, Hazel TG, Muller T, Dugich-Djordjevic MM, McKay RD. Single factors direct the differentiation of stem cells from the fetal and adult central nervous system. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3129–3140. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnabe-Heider F, Wasylnka JA, Fernandes KJ, Porsche C, Sendtner M, Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Evidence that embryonic neurons regulate the onset of cortical gliogenesis via cardiotrophin-1. Neuron. 2005;48:253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Cogswell CA, LoTurco JJ. Neuronal differentiation of precursors in the neocortical ventricular zone is triggered by BMP. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:8853–8862. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08853.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mabie PC, Mehler MF, Kessler JA. Multiple roles of bone morphogenetic protein signaling in the regulation of cortical cell number and phenotype. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:7077–7088. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-07077.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mabie PC, Mehler MF, Marmur R, Papavasiliou A, Song Q, Kessler JA. Bone morphogenetic proteins induce astroglial differentiation of oligoden-droglial-astroglial progenitor cells. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:4112–4120. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04112.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakashima K, Yanagisawa M, Arakawa H, Kimura N, Hisatsune T, Kawabata M, Miyazono K, Taga T. Synergistic signaling in fetal brain by STAT3-Smad1 complex bridged by p300. Science. 1999;284:479–482. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viti J, Gulacsi A, Lillien L. Wnt regulation of progenitor maturation in the cortex depends on Shh or fibroblast growth factor 2. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:5919–5927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05919.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lie DC, Colamarino SA, Song HJ, Desire L, Mira H, Consiglio A, Lein ES, Jessberger S, Lansford H, Dearie AR, Gage FH. Wnt signalling regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nature. 2005;437:1370–1375. doi: 10.1038/nature04108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams BP, Park JK, Alberta JA, Muhlebach SG, Hwang GY, Roberts TM, Stiles CD. A PDGF-regulated immediate early gene response initiates neuronal differentiation in ventricular zone progenitor cells. Neuron. 1997;18:553–562. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80297-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menard C, Hein P, Paquin A, Savelson A, Yang XM, Lederfein D, Barnabe-Heider F, Mir AA, Sterneck E, Peterson AC, Johnson PF, Vinson C, Miller FD. An essential role for a MEK-C/EBP pathway during growth factor-regulated cortical neurogenesis. Neuron. 2002;36:597–610. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abelson JF, Kwan KY, O’Roak BJ, Baek DY, Stillman AA, Morgan TM, Mathews CA, Pauls DL, Rasin MR, Gunel M, Davis NR, Ercan-Sencicek AG, Guez DH, Spertus JA, Leckman JF, Dure LSt, Kurlan R, Singer HS, Gilbert DL, Farhi A, Louvi A, Lifton RP, Sestan N, State MW. Sequence variants in SLITRK1 are associated with Tourette’s syndrome. Science. 2005;310:317–320. doi: 10.1126/science.1116502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan G, Martinowich K, Chin MH, He F, Fouse SD, Hutnick L, Hattori D, Ge W, Shen Y, Wu H, ten Hoeve J, Shuai K, Sun YE. DNA methylation controls the timing of astrogliogenesis through regulation of JAK-STAT signaling. Development. 2005;132:3345–3356. doi: 10.1242/dev.01912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takizawa T, Nakashima K, Namihira M, Ochiai W, Uemura A, Yanagisawa M, Fujita N, Nakao M, Taga T. DNA methylation is a critical cell-intrinsic determinant of astrocyte differentiation in the fetal brain. Dev. Cell. 2001;1:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi-Tezuka M, Yoshida Y, Fukada T, Ohtani T, Yamanaka Y, Nishida K, Nakajima K, Hibi M, Hirano T. Gab1 acts as an adapter molecule linking the cytokine receptor gp130 to ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:4109–4117. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molofsky AV, Pardal R, Iwashita T, Park IK, Clarke MF, Morrison SJ. Bmi-1 dependence distinguishes neural stem cell self-renewal from progenitor proliferation. Nature. 2003;425:962–967. doi: 10.1038/nature02060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molofsky AV, He S, Bydon M, Morrison SJ, Pardal R. Bmi-1 promotes neural stem cell self-renewal and neural development but not mouse growth and survival by repressing the p16Ink4a and p19Arf senescence pathways. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1432–1437. doi: 10.1101/gad.1299505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noonan JA. Noonan syndrome. An update and review for the primary pediatrician. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) 1994;33:548–555. doi: 10.1177/000992289403300907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee DA, Portnoy S, Hill P, Gillberg C, Patton MA. Psychological profile of children with Noonan syndrome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2005;47:35–38. doi: 10.1017/s001216220500006x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida R, Hasegawa T, Hasegawa Y, Nagai T, Kinoshita E, Tanaka Y, Kanegane H, Ohyama K, Onishi T, Hanew K, Okuyama T, Horikawa R, Tanaka T, Ogata T. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase, nonreceptor type 11 mutation analysis and clinical assessment in 45 patients with Noonan syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;89:3359–3364. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]