Abstract

Objective

Migraine is a common co-morbidity of bipolar disorder (BD), and is more prevalent in women than men. We hypothesized co-morbid migraine would be associated with features of illness and psychosocial risk factors which would differ by gender and impact outcome.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted to assess association between self-reported, physician-diagnosed migraine, clinical variables of interest and mood outcome in subjects with DSM-IV BD (N=412) and healthy controls (HC, N=157) from the Prechter Longitudinal Study of Bipolar Disorder, 2005–2010. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Migraine was more common in BD (31%) than HC (6%), and had elevated risk in BD women compared to men (OR 3.5, CI 2.1, 5.8). In men, migraine was associated with BPII (OR 9.9, CI 2.3, 41.9) and mixed symptoms (OR 3.5, CI 1.0, 11.9). Migraine was associated with an earlier age at onset of BD by 2 years, more severe depression (B =.13, p=.03), and more frequent depression longitudinally (B =.13, p=.03). Migraine was associated with childhood trauma (p<.02) and high neuroticism (p<.01), and protective factors included high family adaptability (p=.05) and high extraversion (p=.01).

Conclusion

Migraine is a common co-morbidity with BD and may impact long-term outcome of BD, particularly depression. Clinicians should be alert for migraine co-morbidity in women, and in men with BPII. Effective treatment of migraine may impact mood outcome in BD as well as headache outcome. Joint pathophysiological mechanisms between migraine and BD may be important pathways for future study of treatments for both disorders.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is an illness that affects 2.1% of the population,1 and is one of the top 10 contributors of years of life lived with disability for persons ages 15–44.2 In addition, health care for BD costs more on a per capita basis than for depression, asthma, coronary artery disease, or diabetes,3 and comorbid medical conditions negatively affect quality of life and contribute to the burden of illness.4–6 Migraine is a common comorbidity of BD. In population-based studies, the rate of migraine in the general population is 9–15%,7–12 whereas the rate of migraine co-morbidity with BD is 16–54%.9,10,13–17

Migraine is more prevalent in women (15–20%) than men (6%),7,12 and though BD has no gender differential, comorbidities that affect women at a higher rate may be associated with a different course of illness or presentation of BD.18 Women with BD are at higher risk for bipolar II disorder (BPII), co-morbid anxiety disorders, and suicide attempts.19,20 We hypothesized that individuals with co-morbid migraine and BD have features of more severe illness such as earlier age at onset, mixed symptoms, suicidal ideation and psychosis, more frequent, severe and variable mood during longitudinal follow-up, and more severe psychosocial risk factors such as trauma and stressful life events. Neuroticism, a tendency to experience negative affect such as depressed mood and anxiety, has been associated with both migraine,21 and BD,22 and we hypothesized that neuroticism would be elevated in those with migraine and BD. We hypothesized that the presentation of migraine in BD would differ by gender, specifically that women with migraine would be more likely to have BPII, rapid cycling, anxiety disorders, and suicide attempts. By identifying risk factors and outcomes associated with comorbid migraine, we highlight the need for attention to the frequent comorbidity of migraines in BD and the possibility of treatments that target both illnesses.

Methods

We retrospectively investigated differences in baseline characteristics and longitudinal outcome in 412 subjects with BD (270 F; 142 M) and 157 healthy control subjects (86 F; 71 M) with and without comorbid migraine. Patients with BD, and healthy controls with no personal or family history of mood or psychotic disorder were recruited to the Prechter Longitudinal Study of BD at the University of Michigan between 2005 and 2010. This study was approved by the UM IRB. Diagnostic interviews were completed with the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS),23 and clinicians rated mood with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,24 and the Young Mania Rating Scale.25 Interviewers included physicians, psychologists, and masters-level mental health professionals, and a best-estimate procedure by at least two of the study clinicians was used to verify diagnoses26 The DIGS interview captured history of psychopathology. Medical history was elucidated in the DIGS through a series of questions to determine if the subject had a physician-diagnosed medical conditions, including migraine. If a subject reported a diagnosis of migraine, follow-up questions determined age at onset and an unstructured description of clinical features of migraine. Subjects were measured for height and weight. A subset of subjects also completed questionnaires at baseline including the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ);27 Life Events Occurrence Survey (LEOS);28 Life Events Checklist (LEC);29 Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale II (FACES II);30 and NEO-Personality Index – Revised (NEO-PI-R).31 The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)32 and the Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM)33 were completed every 2 months for the follow-up period of up to 5 years. Baseline depressive symptoms were reported using the HDRS 21 plus atypical items. Values of continuous variables were compared between euthymic group and the control group and gender differences in the BD group were compared using independent sample t-test, with the exception of frequency of mood symptom scores and childhood trauma scale sexual abuse subscale, which were compared using the Mann Whitney U test due to highly skewed distribution. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square test. A logistic regression model was constructed with migraine presence as the dependent variable and BD, sex, body mass index (BMI) and age as independent variables. A second logistic regression model was constructed in the BD sample only, with migraine presence as the dependent variable, and sex, rapid cycling, SNRI use, BMI, BPII and mixed symptoms as independent variables. Mixed symptoms were captured in the DIGS and defined as a history of presence of symptoms of the opposite pole during at least one week of a mood episode: subsyndromal manic symptoms during depression (mean number of symptoms: 3.10 +/− 3.38) or subsyndromal depressive symptoms during mania (mean number of symptoms: 2.81 +/− 2.20).34 Because bivariate testing showed odds for BPII and rapid cycling were increased in men with BD, a third logistic regression model was constructed for BD men only, including migraine presence as the dependent variable, BPII, mixed symptoms, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) use, BMI, and rapid cycling.

Mood outcomes were characterized by severity, variability, and frequency of clinically significant symptoms of depression or mania through the duration of follow-up, which differed for each participant. The severity of depression outcome was defined for each individual by the maximum PHQ-9 score over follow up; the severity of mania outcome was defined for each individual by the maximum ASRM score over follow up. The variability of the depression outcome was defined for each individual by the standard deviation in PHQ-9 scores over the duration of follow-up; the variability of the mania outcome was defined by the standard deviation in ASRM scores over the duration of follow-up. The frequency of clinically significant depressive or manic symptoms was defined as the proportion of the follow-up period that the individual had a PHQ-9 or ASRM score over 5. Multivariable linear regression models were created to determine predictors of mood outcome. The alpha level for significance was set at .05 and the level for trend toward significance was set at .10.

Results

Demographic and clinical description (Supplementary eTable 1)

Migraine was significantly more likely to be present in the BD as compared to the healthy control group (BD: n=127, 31%; HC: n=10, 6%, p=<1×10−3). Migraine comorbidity was much higher in females than males in both the HC and BD groups: ninety percent of migraine sufferers were female in the control group, 83% in the BD group (p=1×10−6). BMI was higher in the BD group than the control group (p=1×10−6) and age at interview was also higher in the BD group (p<1×10−3). Migraine onset occurred at a mean of 18 +/− 11 years old in the control group and 22+/− 12 years old in the BD group, however no statistical difference was detected (p=.30), potentially due to the small number of those with migraine in the control group. Migraine age at onset in the BD group was on average 6 years after the age at onset of BD (age 16 +/− 7).

Clinical correlates associated with migraine in the BD group

We investigated the strength of bivariate association between clinical characteristics and migraine in the BD group; results are shown in Table 1 for the entire sample and shown in Table 2a for women and Table 2b for men. (Supplementary eTable 3 shows results by gender and BPI/BPII diagnosis). Female sex increased odds of migraine (Table 1, OR 3.5, CI 2.1–5.8), and BMI was marginally associated with migraine (r=.11 p=.05) but age was not (r=−.02, p=.70). Age at onset of BD was not associated with migraine (r=−.05, p=.27). A diagnosis of BPII increased the odds of migraine (OR 2.1, CI 1.2–3.6) when compared to BPI, and in men, the diagnosis of BPII increased the odds of migraine by a greater amount (OR 4.2, CI 1.4–12.4). A history of rapid cycling increased the odds of migraine in men (Table 2b, OR 3.5, CI 1.4–8.8). A history of mixed symptoms increased the odds of migraine in women (Table 2a, OR 1.7, CI 1.0–2.9) and when combined by gender (Table 2, OR 2.0, CI 1.3–3.0). The definition of mixed symptoms included a history of subsyndromal mixed episodes, whereas a history of mixed episodes included only mixed episodes as defined by DSM-IV criteria. Drug use disorder increased the odds of migraine in women (Table 2a, OR 1.9, CI 1.0–3.7). The odds of mixed episodes, psychosis, suicide attempt, anxiety disorder, or alcohol use disorder were not increased in the migraine group (p>.05). The number of depressive and hypomanic episodes reported at baseline were correlated with migraine (p<.01). Baseline depressive symptoms were significantly correlated with migraine (Table 2, r=.26, p<1×10−3), but baseline manic symptoms were not (Table 2, p=.55).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics & Clinical Characteristics in BD group: Comparing Those With And Without Migraine

| Characteristic | No migraine | Migraine | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=285) | (n=127) | r/OR a | p/95% CI | |

| Female, n(%) | 165 (58) | 105 (83) | 3.5 | 2.1–5.8 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.6 (6.0) | 30.2 (7.8) | 0.11 | 0.07 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 38 (14) | 39 (12) | −0.02 | 0.70 |

| BD age at onset, mean (SD) | 18.5 (8.2) | 16.2 (6.9) | −0.05 | 0.27 |

| BPI, n(%) | 223 (78) | 83 (65) | refb | refb |

| BPII, n(%) | 37 (13) | 29 (23) | 2.1 | 1.2–3.6 |

| SABP, n (%) | 7 (3) | 6 (5) | N/A | N/A |

| BPNOS, n (%) | 18 (6) | 9 (7) | N/A | N/A |

| Rapid Cycling, n(%) | 89 (31) | 52 (41) | 1.5 | 1.0–2.4 |

| History of Mixed symptoms, n(%) | 102 (40) | 63 (56) | 2.0 | 1.3–3.0 |

| History of Mixed episodes | 68 (26) | 40 (36) | 1.6 | 1.0–2.5 |

| History of Psychosis, n(%) | 159 (59) | 63 (52) | 0.75 | 0.5–1.2 |

| History of Suicide Attempt, n(%) | 110 (39) | 57 (43) | 1.3 | 0.8–1.9 |

| Anxiety disorder, n(%) | 104 (37) | 52 (41) | 1.2 | 0.8–1.9 |

| Drug use disorder, n(%) | 51 (18) | 28 (22) | 1.3 | 0.8–2.2 |

| Alcohol use disorder, n(%) | 127 (45) | 58 (46) | 1.1 | 0.7–1.6 |

| Manic episodes, median (IQR) | 2 (4) | 2 (7) | −0.06 | 0.41 |

| Depression episodes, median (IQR) | 5 (16) | 10 (30) | 0.22 | <0.01 |

| Hypomanic episodes, median (IQR) | 3.5 (20) | 12 (40) | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| (n=147) | n=(70) | r (mig) | p | |

| Baseline depression, mean (SD) | 11.28 (9.90) | 17.38 (12.92) | 0.26 | 1×10−3 |

| Baseline mania, mean (SD) | 2.88 (4.89) | 3.29 (3.98) | 0.04 | 0.55 |

| CTQ emotional abuse, mean (SD) | 11.41 (5.86) | 13.76 (6.14) | 0.18 | 0.01 |

| CTQ physical abuse, mean (SD) | 7.86 (4.10) | 8.61 (4.67) | 0.08 | 0.23 |

| CTQ sexual abuse, median (IQR) | 5 (4) | 6 (11) | 0.17 | 4×10−3 |

| CTQ emotional neglect, mean (SD) | 11.84 (5.61) | 14.03 (6.08) | 0.18 | 0.01 |

| CTQ physical neglect, mean (SD) | 8.65 (2.47) | 8.81 (2.73) | 0.03 | 0.67 |

| FACES II cohesion, mean (SD) | 3.94 (2.11) | 3.63 (1.97) | −0.07 | 0.30 |

| FACES II adaptability, mean (SD) | 3.91 (2.05) | 3.40 (1.94) | −0.12 | 0.08 |

| LEOS Undesirable events, mean (SD) | 2.12 (2.52) | 1.99 (1.97) | −0.03 | 0.69 |

| LEC life events scale, mean (SD) | 4.54 (3.32) | 5.03 (3.73) | 0.07 | 0.33 |

| Neuroticism, mean (SD) | 60.21 (13.58) | 66.40 (12.62) | 0.22 | 2×10−3 |

| Extraversion, mean (SD) | 50.28 (11.62) | 46.31 (11.84) | −0.16 | 0.02 |

| Openness, mean (SD) | 56.73 (12.24) | 58.59 (13.30) | 0.07 | 0.31 |

| Agreeableness, mean (SD) | 49.07 (12.78) | 47.33 (12.77) | −0.06 | 0.35 |

| Conscientiousness, mean (SD) | 43.47 (13.90) | 42.77 (13.41) | −0.02 | 0.73 |

Abbreviations: Body Mass Index (BMI); Bipolar I Disorder (BPI); Bipolar II Disorder (BPII); Schizoaffective Disorder, Bipolar Type (SABP); Bipolar Disorder NOS (BPNOS); Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ); Life Events Occurrence Survey (LEOS); Life Events Checklist (LEC); Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale II (FACES II); Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness from the Five Factor model NEO-Personality Index – Revised (NEO-PI-R). Baseline depression symptoms were measured with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-29), baseline manic symptoms were measured with the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS).

r (mig) = Pearson’s r reported for correlation between normally distributed continuous variables and migraine, Spearman’s r reported for mania, hypomania, depression number of episodes and CTQ sexual abuse and migraine; OR (95% CI) reported for categorical variables.

Pearson’s chi-square comparisons done for BPII using BPI as the reference group

Table 2a.

Clinical Characteristics in BD Group by Gender: Comparing Women With And Without Migraine

| Characteristic | No migraine | Migraine | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=165) | (n=105) | r/ORa | p/95% CI | |

| BPI, n(%) | 123 (83) | 69 (76) | Refb | Refb |

| BPII, n(%) | 25 (17) | 22 (24) | 1.6 | 0.8–3.0 |

| Rapid cycling, n(%) | 58 (35) | 40 (38) | 1.1 | 0.7–1.9 |

| Mixed Symptoms, n(%) | 67 (44) | 53 (58) | 1.7 | 1.0–2.9 |

| Mixed Episodes, n(%) | 41 (27) | 33 (36) | 1.5 | 0.9–2.6 |

| Psychosis, n(%) | 86 (55) | 52 (53) | .90 | 0.5–1.5 |

| Suicide attempts, n(%) | 75 (46) | 51 (49) | 1.1 | 0.7–1.8 |

| Anxiety disorder, n(%) | 73 (44) | 43 (41) | 0.9 | 0.5–1.4 |

| Alcohol use disorder, n(%) | 63 (38) | 49 (47) | 1.4 | 0.9–2.3 |

| Drug use disorder, n(%) | 22 (13) | 24 (23) | 1.9 | 1.0–3.7 |

| Manic episodes, median (IQR) | 2 (5) | 2 (8) | −0.01 | 0.94 |

| Depressive episodes, median (IQR) | 5.5 (17) | 10 (25) | 0.19 | <0.01 |

| Hypomanic episodes, median (IQR) | 4 (20) | 12 (40) | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| (n=95) | n=(57) | r (mig) | p | |

| Baseline depression, mean (SD) | 12.24 (10.32) | 17.57 (13.39) | 0.22 | 0.01 |

| Baseline mania, mean (SD) | 2.52 (3.74) | 3.23 (4.06) | 0.09 | 0.27 |

| CTQ emotional abuse, mean (SD) | 12.44 (6.32) | 14.3 (6.14) | 0.14 | 0.08 |

| CTQ physical abuse, mean (SD) | 8.00 (4.53) | 8.68 (4.66) | 0.07 | 0.37 |

| CTQ sexual abuse, median (IQR) | 5 (4) | 7 (12) | 0.18 | 0.03 |

| CTQ emotional neglect, mean (SD) | 12.27 (5.96) | 14.49 (6.05) | 0.18 | 0.03 |

| CTQ physical neglect, mean (SD) | 8.72 (2.6) | 8.81 (2.63) | 0.02 | 0.84 |

| FACES II cohesion, mean (SD) | 3.75 (2.10) | 3.58 (2.03) | −0.04 | 0.63 |

| FACES II adaptability, mean (SD) | 3.71 (2.11) | 3.39 (2.03) | −0.07 | 0.36 |

| LEOS Undesirable events, mean (SD) | 2.19 (2.49) | 2.05 (1.92) | −0.03 | 0.72 |

| LEC life events scale, mean (SD) | 4.63 (3.43) | 4.72 (3.50) | 0.01 | 0.88 |

| Neuroticism, mean (SD) | 60.61 (14.02) | 65.79 (13.09) | 0.18 | 0.03 |

| Extraversion, mean (SD) | 49.57 (11.52) | 46.49 (12.22) | −0.13 | 0.12 |

| Openness, mean (SD) | 57.78 (12.36) | 58.37 (13.90) | 0.02 | 0.79 |

| Agreeableness, mean (SD) | 48.75 (12.70) | 47.02 (13.05) | −0.07 | 0.42 |

| Conscientiousness, mean (SD) | 43.05 (13.88) | 42.02 (12.73) | −0.04 | 0.65 |

Abbreviations: Bipolar I Disorder (BPI); Bipolar II Disorder (BPII); Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ); Life Events Occurrence Survey (LEOS); Life Events Checklist (LEC); Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale II (FACES II); Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness from the Five Factor model NEO-Personality Index – Revised (NEO-PI-R). Baseline depression symptoms were measured with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-29), baseline manic symptoms were measured with the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS).

r (mig) = Pearson’s r reported for correlation between normally distributed continuous variables and migraine, Spearman’s r reported for mania, hypomania, depression number of episodes and CTQ sexual abuse and migraine; OR (95% CI) reported for categorical variables.

Pearson’s chi-square comparisons done for BPII using BPI as the reference group

Table 2b.

Clinical Characteristics in BD Group by Gender: Comparing Men With And Without Migraine

| Characteristic | No migraine | Migraine | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=112) | (n=21) | r/ORa | p/95% CI | |

| BPI, n (%) | 100 (89) | 14 (67) | refb | refb |

| BPII, n (%) | 12 (11) | 7 (33) | 4.2 | 1.4–12.4 |

| Rapid Cycling, n(%) | 31 (26) | 12 (55) | 3.5 | 1.4–8.8 |

| Mixed Symptoms, n(%) | 35 (33) | 10 (50) | 2.0 | 0.8–5.3 |

| Mixed Episodes, n(%) | 27 (26) | 7 (35) | 1.6 | 0.6–4.4 |

| Psychosis, n(%) | 73 (65) | 11 (50) | 0.6 | 0.2–1.4 |

| Suicide Attempts, n(%) | 35 (30) | 6 (27) | 0.9 | 0.3–2.4 |

| Anxiety Disorder, n(%) | 31 (26) | 9 (41) | 2.0 | 0.8–5.1 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder, n(%) | 64 (53) | 9 (41) | 0.6 | 0.2–1.5 |

| Drug Use Disorder, n(%) | 29 (24) | 4 (18) | 0.7 | 0.2–2.2 |

| Manic episodes, median (IQR) | 3 (4) | 1.5 (5) | −0.10 | 0.24 |

| Depressive episodes, median (IQR) | 4 (12) | 6.5 (66) | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| Hypomanic episodes, median (IQR) | 3 (29) | 17.5 (31) | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| (n=52) | n=(13) | r (mig) | p | |

| Baseline depression, mean (SD) | 9.67 (9.02) | 16.54 (11.13) | 0.29 | 0.02 |

| Baseline mania, mean (SD) | 3.56 (6.48) | 3.54 (3.71) | −0.01 | 0.99 |

| CTQ emotional abuse, mean (SD) | 9.52 (4.36) | 11.38 (5.75) | 0.16 | 0.20 |

| CTQ physical abuse, mean (SD) | 7.62 (3.20) | 8.31 (4.91) | 0.08 | 0.54 |

| CTQ sexual abuse, median (IQR) | 5 (4) | 5 (10) | 0.06 | 0.62 |

| CTQ emotional neglect, mean (SD) | 11.06 (4.87) | 12.00 (6.03) | 0.08 | 0.55 |

| CTQ physical neglect, mean (SD) | 8.54 (2.19) | 8.85 (3.26) | 0.05 | 0.69 |

| FACES II cohesion, mean (SD) | 4.29 (2.10) | 3.85 (1.78) | −0.09 | 0.49 |

| FACES II adaptability, mean (SD) | 4.29 (1.90) | 3.46 (1.51) | −0.18 | 0.15 |

| LEOS Undesirable events, mean (SD) | 2.00 (2.58) | 1.69 (2.21) | −0.05 | 0.70 |

| LEC life events scale, mean (SD) | 4.37 (3.14) | 6.39 (4.48) | 0.23 | 0.06 |

| Neuroticism, mean (SD) | 59.48 (12.86) | 69.08 (10.32) | 0.30 | 0.02 |

| Extraversion, mean (SD) | 51.58 (11.78) | 45.43 (10.37) | −0.21 | 0.10 |

| Openness, mean (SD) | 54.81 (11.89) | 59.54 (10.71) | 0.16 | 0.20 |

| Agreeableness, mean (SD) | 49.65 (12.96) | 48.69 (11.85) | −0.03 | 0.81 |

| Conscientiousness, mean (SD) | 44.23 (14.03) | 46.08 (16.25) | 0.05 | 0.69 |

Abbreviations: Bipolar I Disorder (BPI); Bipolar II Disorder (BPII); Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ); Life Events Occurrence Survey (LEOS); Life Events Checklist (LEC); Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale II (FACES II); Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness from the Five Factor model NEO-Personality Index – Revised (NEO-PI-R). Baseline depression symptoms were measured with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-29), baseline manic symptoms were measured with the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS).

r (mig) = Pearson’s r reported for correlation between normally distributed continuous variables and migraine, Spearman’s r reported for mania, hypomania, depression number of episodes and CTQ sexual abuse and migraine; OR (95% CI) reported for categorical variables.

Pearson’s chi-square comparisons done for BPII using BPI as the reference group

Bivariate associations in a subgroup of BD subjects showed a positive correlation between migraine and CTQ emotional abuse (r=.20, p=.01), CTQ sexual abuse (r=.17, p=.4×10−3), CTQ emotional neglect (r=.19, p=.01), and neuroticism (r=.22, p=2×10−3). There was a negative correlation between migraine and extraversion (r=−.16, p=.02), and a trend toward negative correlation with FACES II family adaptability score (r=−.12, p=.08).

Clinical characteristics by gender (Table 2a and Table 2b)

There was no significant difference between rates of migraine in the BPII vs BPI group in the women (OR 1.6, 95% CI 0.8–3.0). Group differences between women with BD and migraine and without migraine included a marginally higher rate of mixed symptoms (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.0–2.9), drug use disorder (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.0–3.7), and baseline report of more lifetime depressive (r−0.19, p<.01) and hypomanic episodes (r=0.13, p=.04). Comparisons of psychosocial factors included higher depressive symptoms in women (r=0.22, p=.01), higher median level of sexual abuse (r=0.18, p=.03), higher level of emotional neglect (r=0.18, p=.03) and higher mean neuroticism (0.18, p=.03).

Group differences in the men included a higher rate of migraine in those with BPII compared to BPI (OR 4.2, 95% CI 1.4–12.4) and higher rates of rapid cycling (OR3.5, 95% CI 1.4–8.8). Baseline reports of lifetime history of depressive episodes (r=0.19, p=.03) and hypomanic episodes showed a trend for difference (r=0.14, p=.09). Psychosocial characteristics that differed between men with and without migraine included more depressive symptoms in the migraine group (r=0.29, p=.02), a trend for association with more life events (r=0.23, p=.06) and higher neuroticism (r=0.3, p=.02).

Use of medication in those with and without migraine

We investigated the prevalence of history of lifetime use of medications for migraine in the groups with and without migraine, particularly because some of the common treatments for migraine include antidepressants which have been suggested to change clinical characteristics of BD, including inducing rapid cycling.35 Valproic acid, topiramate, gabapentin, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) were all more commonly taken by those in the migraine group (p<.02) (Supplementary eTable 2). Monoamine oxidase inhibitors were taken by only 5 subjects in the cohort, 4 without migraine and 1 with migraine.

Lifetime history of SNRI use was associated with rapid cycling (r=.15, p=3×10−3), while TCA showed a trend (r=.10, p=.05) and SSRI use was not associated(r=.05, p=.30). When investigated by diagnosis, correlation between SNRI use and rapid cycling was strongest in SAB (n=14, r=.576, p=.03), followed by BPI (n=312, r=.161, p=.004). Rapid cycling and SNRI use were not correlated in BPII (n=66, r=.013, p=.91) or BPNOS (n=27, r=.090, p=.65). SNRI use was then incorporated into multivariable models that included rapid cycling.

Multivariable models of baseline risk factors for migraine (Table 3)

Table 3.

Multivariable models of correlates of migraine

| Bivariate | Multivariable | Multivariable | Multivariable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r(p)/OR (95% CI) | BD/HC, β(p)a | BD only, β(p)b | BD men, β(p)c | |

| BD | N/A | 6.0 (3.0–12.2) | N/A | N/A |

| Female | 3.5 (2.1–5.8) | 3.9 (2.3–6.8) | 3.0 (1.6–5.6) | --- |

| BMI | .11 (0.05) | 1.04 (1.0–1.1) | b | c |

| Age | −.02 (.70) | --- | --- | --- |

| BD age at onset | −.05 (.27) | --- | --- | --- |

| BPII | 2.1 (1.2–3.6) | --- | b | --- |

| BPII-men | 4.2 (1.4–12.4) | --- | --- | 9.9 (2.3–41.9) |

| Rapid Cycling | 1.5 (0.99–2.4) | --- | 1.7 (0.99–2.9) | c |

| Rapid Cycling, men | 3.5 (1.4–8.8) | --- | --- | --- |

| Mixed symptoms | 2.0 (1.3–3.0) | --- | b | 3.5 (1.0–11.9) |

| Mixed episodes | 1.6 (0.97–2.5) | --- | --- | --- |

| Psychosis | 0.75 (0.49–1.2) | --- | --- | --- |

| Suicide attempt | 1.3 (0.83–1.9) | --- | --- | --- |

| Anxiety disorder | 1.2 (0.79–1.9) | --- | --- | --- |

| Drug use disorder | 1.3 (0.77–2.2) | --- | --- | --- |

| Alcohol use disorder | 1.1 (0.69–1.6) | --- | --- | --- |

controlled for age

controlled for serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) use; body mass index (BMI), BPII, and mixed symptoms eliminated from model by backward selection. “---” indicates variables that were not included in the model.

controlled for SNRI use; BMI, rapid cycling eliminated from model by backward selection. “---” indicates variables that were not included in the model.

BD increased the odds of migraine by 6.0 (CI 3.0, 12.2) when corrected for age, sex and BMI. In those with BD, female sex increased odds of migraine (OR 3.0, CI 1.6, 5.6) and rapid cycling was significant at a trend level (OR 1.7, CI .99, 2.9) when controlled for SNRI use. BMI, BPII and mixed symptoms were eliminated from the final model. In men with BD, BPII (OR 9.9, CI 2.3, 41.9) and mixed symptoms (OR 3.5, CI 1.0, 11.9) were independently associated with migraine after controlling for SNRI use. BMI and rapid cycling were eliminated from the final model.

Longitudinal outcome (Table 4)

Table 4.

Mood Outcome in BD group: Comparing Those With And Without Migraine

| No migraine | Migraine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=168 | n=87 | Multivariablea | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | β(p) | |

| Depression severity | 14.4 (7.2) | 18.3 (6.3) | 3×10−5 | 0.13 (0.03) |

| Mania severity | 7.6 (4.2) | 8.9 (4.6) | 0.03 | 0.08 (0.19) |

| Depression variability | 4.0 (2.3) | 4.6 (2.2) | 0.04 | 0.04 (0.49) |

| Mania variability | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.6) | 0.01 | 0.10 (0.11) |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | p | β(p) | |

| Depression frequency | 0.57 (0.74) | 0.83 (0.48) | <1×10−3 | 0.13 (0.03) |

| Mania frequency | 0.14 (0.42) | 0.17 (0.40) | 0.73 | −0.03 (0.61) |

| Mixed frequency | 0.00 (0.20) | 0.09 (0.20) | 0.06 | 0.01 (0.91) |

Depression symptoms were assessed in longitudinal follow-up using the PHQ-9 and mania symptoms were assessed using the Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM).

Linear regression models included age, BMI, sex, migraine, baseline mood symptoms

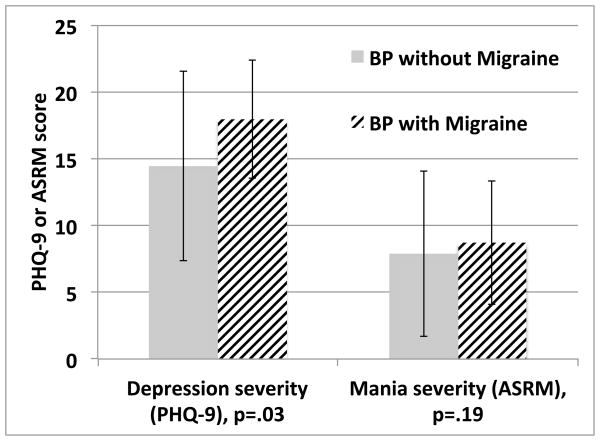

Bivariate comparisons of longitudinal follow-up of subjects showed that subjects with BD and migraine had more severe and frequent depressive symptoms (p<.01), and more severe manic symptoms (p=.03) than those without migraine in group comparisons (Figure 1). Subjects with migraine also had more variability in manic symptoms than those without migraine (p>.01) (Figure 1). There were no gender differences in these outcome variables (p>.05). In multivariable analysis, migraine was a significant predictor of depression severity (B=.13, p=.03) and depression frequency (B=.13, p=.03) over follow-up when controlled for age, BMI and sex and baseline mood symptoms. Migraine did not predict manic severity (p=0.19), variability (p=0.11) or frequency (p=0.61), or depression variability (p=0.49).

Figure 1.

Depression severity over longitudinal follow-up differed between the migraine and non-migraine groups, but mania severity did not differ

Depression severity was assessed using the PHQ-9 and mania severity was assessed using the Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM); Y-axis reflects group mean scores +/− standard deviation on these measures. Models comparing depression and mania severity accounted for age, BMI, sex, BPI vs. BPII.

Conclusion

We found that migraine was highly prevalent in BD and, as in the general population, especially in women with BD. Those with BD and migraine showed a younger age at onset of BD, and a more severe pattern of depression outcome retrospectively and prospectively. Additional factors that were associated with vulnerability to migraine included childhood abuse and neuroticism, and protective factors included family adaptability and extraversion. In this cohort, BPII was not associated with migraine independent of gender. Gender differences emerged in clinical correlates of migraine, including that men with migraines reported more mixed symptoms than men without migraines.

Our results are consistent with population-based studies that find increased co-morbidity with migraine headache in patients with BD.9,10,13–17 We found that in our BD sample, as in both general and clinical populations, migraine were more common in women,10,36,37 though at least one study has shown equal prevalence.17 One study of familial transmission of migraine headache showed no genetic contribution to sex differences, and the authors hypothesized that susceptibility to environmental factors may play a larger role than genetics in the gender differential.36

Consistent with a number of studies, in our cohort, migraine was more common in those with BPII disorder.13,16,37 Our results showed that in this sample the risk of migraine in those with BPII was not independent of the association with female sex. Because both BPII and migraine are more common in women, we could hypothesize the increase in prevalence of migraine in BPII may be due to a gender effect, or the increased prevalence of migraine in females may be due to the increased risk for a BPII illness. However, risk for migraine headache was particularly high in men with BPII, and mixed symptoms were associated with migraine headache in men with BD independent of association with BPII. An association between migraine headache and rapid cycling in men was not significant after accounting for use of SNRI antidepressants, which may increase rapid cycling.38,39 The association between lifetime-use of SNRI antidepressants and lifetime history of rapid cycling is notable, however this study is not designed to distinguish the nature of this association or to determine causality. Further investigation into a longitudinal association between SNRI use and rapid cycling would be warranted.

Our findings are consistent with other studies of migraine headache in BD clinical populations that show that worse severity of BD as evidenced by earlier age at onset, greater psychosocial impairment, and worse depression in those with migraine headache13,17,40 We found that outcome was not gender-dependent, despite gender difference in prevalence of migraine. Younger age at onset of BD, despite the age at onset for migraine headache being after the age of onset of BD, may hint at underlying common pathology between migraine and BD that manifests first as mood symptoms and second as migraine.

Psychosocial factors that correlated with migraine headache in our BD sample included childhood emotional, sexual abuse and emotional neglect, found most strongly in women with BD and migraine. Childhood maltreatment, trauma and abuse have been found to play a role in developing migraine headache and converting episodic to daily migraine.6,41,42 Neuroticism was strongly associated with migraine in both genders, and as neuroticism measures propensity to experience negative affect and stress, those with high neuroticism are less likely to be able to be adaptable and flexible in coping styles.43–45

In converse, we found two factors that were protective against migraine, family adaptability and extraversion. Family adaptability indicates a level of flexibility and support that is likely to reduce stress in the home, and it may be through this reduction of stress that is protective against migraine. Likewise, those who are extroverted are more likely to have a greater social support network, which tends to reduce stress.

Numerous factors are likely to contribute to the co-occurrence of migraine and BD. Genetic factors influence susceptibility to both illnesses, and those with BD and migraine may have a shared pathology.36,46 Abnormal activation cytokine-based inflammatory mechanisms has recently been reported in BD47,48 and in migraine headache,49 and there is evidence for abnormal metabolism of arachidonic acid (AA) in both disorders.50–53 In addition, the effectiveness of anti-epileptic treatments for both BD and migraine headache provides an indication that there is a link in pathophysiological processes between the two disorders.54–57

Our results must be viewed in light of a number of limitations, including that we had only subjective report of diagnosis of migraine and furthermore we have no detail of the outcome of migraine headache in this population. An additional limitation is that this is a group of patients with BD who are followed through a longitudinal study, and this group may not represent the most severe end of the BD spectrum. Strengths include a relatively large sample of well-characterized subjects with BD followed longitudinally.

Migraine is commonly comorbid with BD, is associated with a more severe clinical picture of BD, and is associated with worse outcomes measured prospectively. Women are particularly vulnerable to migraine, as are those with BPII, though men with BPII have a very high rate of migraine. A history of abuse and a personality trait of high neuroticism increase vulnerability to migraine, and high family adaptability and extraversion are protective factors. Further study into the common mechanism underlying migraine headache and BD, as well as effects of treatments on conditions may lead to improved outcomes for people with BD and migraine comorbidity.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Points.

Migraine is commonly associated with more severe bipolar disorder, and worse outcome.

Women with bipolar disorder and men with bipolar II disorder are particularly vulnerable to migraine.

A history of abuse and a personality trait of high neuroticism increase vulnerability to migraine, and high family adaptability and extraversion are protective factors.

Acknowledgments

Sources of financial support: The Heinz C. Prechter Bipolar Research Fund – University of Michigan. The project described was supported by the National Center for Research Resources, GrantKL2 RR033180 (EFHS), and is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant KL2 TR000126. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The sponsors of this research did not have direct influence over the collection, analysis or interpretation of data.

Acknowledgement of assistance: We would like to thank the participants in the Prechter Longitudinal Study of Bipolar Disorder and the dedicated research team of the Prechter Bipolar Group, without whom this work would not be possible.

The Heinz C. Prechter Bipolar Research Fund supported the collection of the data for the Prechter Longitudinal Study of Bipolar Disorder and the Prechter Bipolar Genetic Repository. The data reside at the University of Michigan, and can be requested through inquiries addressed to Dr. Melvin G. McInnis, MD, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109.

Footnotes

Presented at the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Hollywood, Florida December 2–6, 2012.

Disclaimer: E. Saunders, R. Nazir, M. Kamali, K. Ryan, S. Evans, S. Langenecker – none; M. McInnis – Merck Pharmaceuticals (Honoraria for Speaker’s bureau); A. Gelenberg – Zynx (consultanship), Pfeizer Pharmaceutical (investigator-initiated grant through Penn State), Healthcare Technology Systems, Inc. (major stock ownership).

References

- 1.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Who. The World Health Report: 2001: Mental health: new understanding, new hope. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams MD, Shah ND, Wagie AE, Wood DL, Frye MA. Direct costs of bipolar disorder versus other chronic conditions: an employer-based health plan analysis. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC) 2011;62(9):1073–1078. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.9.pss6209_1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amini H, Sharifi V. Quality of life in bipolar type I disorder in a one-year followup. Depression research and treatment. 2012;2012:860745. doi: 10.1155/2012/860745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnan KR. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosom Med. 2005 Jan-Feb;67(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000151489.36347.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Post RM, Altshuler LL, Leverich GS, et al. Role of childhood adversity in the development of medical co-morbidities associated with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013 May;147(1–3):288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breslau N, Merikangas K, Bowden CL. Comorbidity of migraine and major affective disorders. Neurology. 1994 Oct;44(10 Suppl 7):S17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merikangas KR, Angst J, Isler H. Migraine and psychopathology. Results of the Zurich cohort study of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990 Sep;47(9):849–853. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810210057008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Wilkins K, Bouffard B, Soczynska JK, Kennedy SH. The prevalence and impact of migraine headache in bipolar disorder: results from the Canadian Community Health Survey. Headache. 2006 Jun;46(6):973–982. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baptista T, Uzcategui E, Arape Y, et al. Migraine life-time prevalence in mental disorders: concurrent comparisons with first-degree relatives and the general population. Investigacion clinica. 2012 Mar;53(1):38–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen YC, Tang CH, Ng K, Wang SJ. Comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine sufferers in a national database in Taiwan. The journal of headache and pain. 2012 Jun;13(4):311–319. doi: 10.1007/s10194-012-0447-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jette N, Patten S, Williams J, Becker W, Wiebe S. Comorbidity of migraine and psychiatric disorders--a national population-based study. Headache. 2008 Apr;48(4):501–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz A, Cervantes P, Zlotnik G, et al. Cross-prevalence of migraine and bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010 Jun;12(4):397–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dilsaver SC, Benazzi F, Oedegaard KJ, Fasmer OB, Akiskal KK, Akiskal HS. Migraine headache in affectively ill latino adults of mexican american origin is associated with bipolarity. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(6):302–306. doi: 10.4088/PCC.08m00728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Soczynska JK, et al. Medical comorbidity in bipolar disorder: implications for functional outcomes and health service utilization. Psychiatr Serv. 2006 Aug;57(8):1140–1144. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.8.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fasmer OB, Oedegaard KJ. Clinical characteristics of patients with major affective disorders and comorbid migraine. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2001 Jul;2(3):149–155. doi: 10.3109/15622970109026801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahmood T, Romans S, Silverstone T. Prevalence of migraine in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 1999 Jan-Mar;52(1–3):239–241. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saunders EF, Fitzgerald KD, Zhang P, McInnis MG. Clinical features of bipolar disorder comorbid with anxiety disorders differ between men and women. Depress Anxiety. 2012 Aug;29(8):739–746. doi: 10.1002/da.21932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldassano CF, Marangell LB, Gyulai L, et al. Gender differences in bipolar disorder: retrospective data from the first 500 STEP-BD participants. Bipolar disorders. 2005;7(5):465–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldassano CF. Illness course, comorbidity, gender, and suicidality in patients with bipolar disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 11):8–11. Journal Article. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis RE, Smitherman TA, Baskin SM. Personality traits, personality disorders, and migraine: a review. Neurological sciences: official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2013 May;34 (Suppl 1):S7–10. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim B, Joo YH, Kim SY, Lim JH, Kim EO. Personality traits and affective morbidity in patients with bipolar I disorder: the five-factor model perspective. Psychiatry Res. 2011 Jan 30;185(1–2):135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nurnberger JI, Jr, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, et al. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51(11):849–859. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002. discussion 863–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson WD, Belanger A, Weissman MM. Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: a methodological study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1982;39(8):879–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994 Aug;151(8):1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKee SA, AM, Kochetkova A, Maciejewski P, O’Malley S, Krishnan-Sarin S, Mazure CM. A new measure for assessing the impact of stressful events on smoking behavior. Annual Meeting the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; Prague, CZ. 2005; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson JH, McCutcheon S. Assessing life stress in older children and adolescents: Preliminary findings with the life events checklist. In: Sarason IE, Speilberger CD, editors. Stress and Anxiety. New York: Hemishphere Publishing Corporation; 1980. pp. 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olson DH, Russell CS, Sprenkle DH. Circumplex model of marital and family systems: VI. Theoretical update. Fam Process. 1983 Mar;22(1):69–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1983.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Personality in adulthood: a six-year longitudinal study of self-reports and spouse ratings on the NEO Personality Inventory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988 May;54(5):853–863. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman EG, Hedeker D, Peterson JL, Davis JM. The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale. Biological psychiatry. 1997;42(10):948–955. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swann AC, Steinberg JL, Lijffijt M, Moeller GF. Continuum of depressive and manic mixed states in patients with bipolar disorder: quantitative measurement and clinical features. World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) 2009 Oct;8(3):166–172. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sidor MM, Macqueen GM. Antidepressants for the acute treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011 Feb;72(2):156–167. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09r05385gre. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Low NC, Cui L, Merikangas KR. Sex differences in the transmission of migraine. Cephalalgia. 2007 Aug;27(8):935–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fasmer OB. The prevalence of migraine in patients with bipolar and unipolar affective disorders. Cephalalgia. 2001 Nov;21(9):894–899. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2001.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fountoulakis KN, Kontis D, Gonda X, Yatham LN. A systematic review of the evidence on the treatment of rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2013 Mar;15(2):115–137. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valenti M, Pacchiarotti I, Bonnin CM, et al. Risk factors for antidepressant-related switch to mania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012 Feb;73(2):e271–276. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brietzke E, Moreira CL, Duarte SV, et al. Impact of comorbid migraine on the clinical course of bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2012 Aug;53(6):809–812. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tietjen GE, Brandes JL, Peterlin BL, et al. Childhood maltreatment and migraine (part I). Prevalence and adult revictimization: a multicenter headache clinic survey. Headache. 2010 Jan;50(1):20–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tietjen GE, Brandes JL, Peterlin BL, et al. Childhood maltreatment and migraine (part II). Emotional abuse as a risk factor for headache chronification. Headache. 2010 Jan;50(1):32–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barnett JH, Huang J, Perlis RH, et al. Personality and bipolar disorder: dissecting state and trait associations between mood and personality. Psychol Med. 2011 Aug;41(8):1593–1604. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uliaszek AA, Zinbarg RE, Mineka S, et al. A longitudinal examination of stress generation in depressive and anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011 Oct 17; doi: 10.1037/a0025835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Shi S, Yang F, et al. Patterns of co-morbidity with anxiety disorders in Chinese women with recurrent major depression. Psychol Med. 2011 Nov 30;:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S003329171100273X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dilsaver SC, Benazzi F, Oedegaard KJ, Fasmer OB, Akiskal HS. Is a Family History of Bipolar Disorder a Risk Factor for Migraine among Affectively Ill Patients? Psychopathology. 2009;42(2):119–123. doi: 10.1159/000204762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Konradi C, Sillivan SE, Clay HB. Mitochondria, oligodendrocytes and inflammation in bipolar disorder: Evidence from transcriptome studies points to intriguing parallels with multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2012 Jan;45(1):37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldstein BI, Kemp DE, Soczynska JK, McIntyre RS. Inflammation and the phenomenology, pathophysiology, comorbidity, and treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of the literature. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2009;70(8):1078–1090. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08r04505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brietzke E, Mansur RB, Grassi-Oliveira R, Soczynska JK, McIntyre RS. Inflammatory cytokines as an underlying mechanism of the comorbidity between bipolar disorder and migraine. Med Hypotheses. 2012 May;78(5):601–605. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sublette ME, Bosetti F, DeMar JC, et al. Plasma free polyunsaturated fatty acid levels are associated with symptom severity in acute mania. Bipolar disorders. 2007;9(7):759–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McNamara RK, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, Dwivedi Y, Pandey GN. Selective deficits in erythrocyte docosahexaenoic acid composition in adult patients with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2010;126(1–2):303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soares JK, Rocha-de-Melo AP, Medeiros MC, et al. Conjugated linoleic acid in the maternal diet differentially enhances growth and cortical spreading depression in the rat progeny. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012 Oct;1820(10):1490–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramsden CE, Mann JD, Faurot KR, et al. Low omega-6 vs. low omega-6 plus high omega-3 dietary intervention for chronic daily headache: protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2011;12:97. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bond DJ, Lam RW, Yatham LN. Divalproex sodium versus placebo in the treatment of acute bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2010 Aug;124(3):228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Engmann B. Bipolar affective disorder and migraine. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:389851. doi: 10.1155/2012/389851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pope HG, Jr, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Jr, Hudson JI. Valproate in the treatment of acute mania. A placebo-controlled study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48(1):62–68. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250064008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vieta E, Sanchez-Moreno J. Acute and long-term treatment of mania. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2008;10(2):165–179. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.2/evieta. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.