Abstract

Introduction

Assessing blood-donor haemoglobin (Hb) is a worldwide screening requirement against inappropriate donation. The pre-donation Hb (which should be at least 12.5 g/dL in women and 13.5 g/dL in men) is usually determined in capillary blood from a finger prick, using a spectrophotometer which reveals the absorbance of blood haemolysed in a microcuvette. New non-invasive methods of measuring Hb are now available.

Materials and methods

In the first semester of 3 consecutive years three different strategies were employed to screen donors for anaemia at the moment of donation. In 2011 all whole-blood donors underwent the finger-prick method using azide-methaemoglobin: the test’s negative predictive value (NPV) was determined by comparison with the sub-threshold Hb values ascertained by haemocytometry of test-tube blood drawn at the start of the donation. In 2012 the donor evaluation was based on NBM 200 occlusion spectrophotometry. The same approach was kept in 2013, but a haemocytometry test was added on a pre-donation venous sample drawn from donors who, though fit to donate, had previous critical Hb values in their clinical records.

Results

In 2011, the NPV (in 3,856 donors) was 86% for women and 95% for men; in 2012 (3,966 donors), the values were 85% and 95%, respectively, and in 2013 (3,995 donors) they were 91% and 97%, respectively. Fisher’s test for contingency tables revealed no statistically significant differences between 2011 and 2012, but the 2013 results were a significant improvement.

Discussion

Measuring Hb by finger prick is not wholly satisfactory since, above all in women, the result of this screening may subsequently be belied by the haemocytometry finding of an unacceptable Hb value. Using a non-invasive method does not diminish the selective efficiency. In women, in particular, adding a haemocytometric test on a venous sample significantly improves donor selection and avoids the risk of inappropriate donation or blood-letting.

Keywords: donor selection, pre-donation haemoglobin, non-invasive method

Introduction

When prospective donors, previously declared fit for donation, come to a collection site to donate whole blood, the practice is to assess their haemoglobin (Hb)1, with the purpose of avoiding further loss of blood components by those already anaemic or with low Hb levels (generally considered to be <13.5 g/L in men and <12.5 g/L in women). In deferred donors this test is followed by a global fitness evaluation including, among other assessments, a haemocytometry test on a sample of venous blood. The quick test is generally performed on a capillary sample. In the past it was taken from the ear-lobe2 in far from standardised conditions; currently it is collected by finger prick to the finger-pad3. The copper sulphate test to determine Hb proved unreliable due to variability in the droplet of capillary blood obtained and has largely been replaced by a photometric test in a microcuvette4. Historically, this test was based on the formation of cyanomethaemoglobin5 in a Drabkin solution; this was then replaced by sodium azide6 forming azide-methaemoglobin and later still by direct photometric evaluation of the Hb content, without addition of reagents7. Of late, devices have been marketed that perform photometric Hb evaluation directly in the surface veins of the donor’s hand - a non-invasive technique8.

Over the last 3 years, the method of pre-donation Hb determination has changed at the Immunohaematology and Transfusion Medicine Collection Site of S. Orsola Malpighi Hospital. In 2011 the standard technique was the traditional finger-prick test and Hb reading by EKF Diagnostics’ Hemo Control (EKF Diagnostics Holdings plc, Cardiff, Wales, UK). In 2012, after due assessment of the non-invasive techniques on the market, we changed over to NBM 200 occlusion spectroscopy by OrSense (OrSense Co., Petah-Tikya, Israel). At the start of donation itself we continued to take a venous sample from the blood-line on which we later performed haemocytometry on a Beckman Coulter’s AcT-5 diff cell-counter (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA).

In 2013 what had been a sporadic practice, the doctor-in-charge deciding if and when to take a pre-donation sample for haemocytometry testing before declaring a donor fit, became a routine procedure whenever the Information Technology donor management system gave the alarm. This alarm (haemocytometry evaluation before donation) derived from low Hb or ferritin values in the past. In all three periods cell counter haemocytometry was, in retrospect, the reference method for all donors, but only in the third period did some selected donors have a cell counter haemocytometry result before the admission to donation.

The present study was intended to evaluate these three different approaches to donor selection.

Materials and methods

The Hemo Control method

In the Hemo Control method, a single drop of blood from a finger prick is placed in a micro test-tube containing a reagent buffer solution (sodium desoxycolate, sodium nitrite, potassium cyanide or sodium azide). Sodium desoxycolate dissolves the red cell walls causing haemolysis. The Hb within the erythrocytes is released into the solution. The bivalent iron in oxyhaemoglobin and desoxyhaemoglobin is oxidised by sodium nitrite (NaNO2) into a trivalent iron, changing the Hb conformation into methaemoglobin. When bound to azide ions, methaemoglobin yields maximum light absorption at a wavelength between 540–575 nm. This photometric detection method works by determining the intensity of the light passing through the haemolysed blood sample. The difference between the light emitted and that which gets through is directly proportional to the Hb concentration in the sample, which is what accounts for the light absorption.

The NBM 200 method

The NBM 200 method involves a non-invasive device to measure the heartbeat and Hb concentration at the base of a finger or thumb. The system comprises a ring-shaped re-usable sensor/probe, placed for preference around the thumb, and a small portable monitor with a graphic display, containing a microprocessor that calculates the result and shows it on the screen. The probe is composed of eight diodes generating bands of light in the red (610 nm) and infrared (935 nm) fields, plus a photocell receiving the light after it has passed through the patient’s skin and circulation. At those wavelengths Hb absorbs light. The photocell registers the light penetrating the thumb and converts the intensity of the light spectrum into an electronic signal which is sent to the device to be processed and the result displayed. The system uses Occlusive Spectroscopy technology patented by OrSense, and combines high-sensitivity optic measurement with temporary occlusion of the arterial blood flow at the base of the thumb, thanks to an inflatable collar. A reading is taken on five consecutive occlusion cycles.

Haemocytometry

The haemocytometric technique uses the Beckman Coulter Ac-T 5 diff cell counter, an automatic haematological analyser for in vitro diagnosis. This counter can analyse 26 standard blood parameters, calculate the platelet formula, and screen for the leucocyte formula on five populations; it includes a built-in sampler which automatically stirs the sample by full inversion, a barcode reader, and a dedicated management system. The volume of the sample aspirated, regardless of the sampling mode, is 30 μL of whole blood on CBC mode (12-parameter analysis without leucocyte formula). The device divides the sample into aliquots directly from the aspirator probe, and automatically proceeds to dilute these in the respective chambers. The Hb concentration is determined by spectrophotometry set at a wavelength of 550 nm and using AC-T 5 diff Hgb Lyse reagent (a water-based solution containing potassium cyanide and quaternary ammonium salts). When the lytic reagent is added to a whole-blood sample, the tensioactive properties of quaternary ammonium salts lyse the red blood cells, destroying the cell membrane and thus releasing Hb into the solution. The Hb released reacts chemically with the potassium cyanide to form a chromogene suitable for Hb determination: cyanmethaemoglobin. A ray of white light, with a wavelength of 550 nm, passes through the reading cell. The quantity (intensity) of the light absorbed by the sample is directly proportional to the Hb concentration.

In the first half-years of 3 consecutive calendar years (2011, 2012, and 2013) three different strategies were used to screen donors against inappropriate donation and consequent anaemia. In the first half of 2011 a total of 3,856 donors (2,813 men and 1,013 women) had their pre-donation haemoglobin levels measured by finger prick and the azide-methaemoglobin method using EFK Diagnostics’ Hemo Control. In the first semester of 2012, in 3,966 donors (2,945 men and 1,021 women) the non-invasive method used was OrSense’s NBM 200 occlusion spectrophotometer. At the outset of donation in all cases venous blood was drawn and later tested by the Beckman Coulter AcT-5 diff AL cell-counter haemocytometry method. During clinical test validation the pre-donation Hb value was compared with the later haemocytometry test value from venous blood at the start of the donation. The donor admission was based on the Hb value found in the screening test, but cell counter haemocytometry was performed later on a venous blood sampled at the beginning of the donation a few minutes after the screening. From 2011 onward, donors who were proven unfit by the haemocytometric method on the first blood drawn had a “donor alarm” activated on their clinical file. Over the first half of 2013, out of the 3,995 donors, (2,895 men and 1,100 women) those belonging to this last group underwent pre-donation Hb screening on a venous sample using the Beckman Coulter AcT-5 diff cell-counter haemocytometric method, instead of the NBM 200 non-invasive technique then being used at the S. Orsola-Malpighi Hospital Collection Site and employed as the sole pre-donation screening method for donors without a history of previously being unfit for blood donation.

Results

The global results on the 3,995 donors in 2013, first semester, together with those relating to 2011 and 2012 (semester 1), are shown in Tables I, II and III. The study confirms the high degree of specificity achieved by the three pre-donation approaches: 99.76% for women and 99.89% for men with the Hemo Control method (Table I); 95.12% and 98.89%, respectively, by the NBM 200 method (Table II); and 99.24% and 99.93% respectively, by NBM 200 + Beckman cell-counter on certain selected venous samples (Table III). The sensitivity of the two methods used in 2011 and 2012 (32.14% for women and 13.22% for men by Hemo Control; 32.34% for women and 14.47% for men by NBM 200) was comparably low. It improved when the strategy used was NBM 200 + Beckman cell-counter (45.76% for women and 36.03% for men) on donors selected by history. A similar improvement emerged from calculation of the negative predictive value, which was 86.40% for women and 94.58% for men by Hemo Control; 85.15% and 95.30%, respectively, using NBM 200, and 90.51% and 96.94%, respectively, using a combination of NBM 200 + Beckman cell-counter. In a very few cases (1 in 2011 and 1 in 2013) the value of the venous Hb was below 11 g/dL (10.5 g/dL and 10.8 g/dL, respectively).

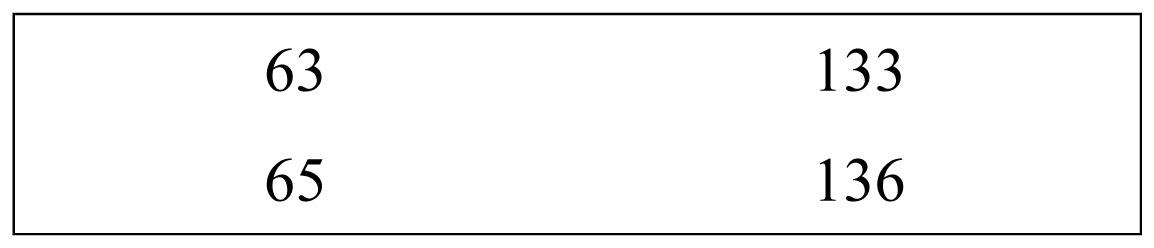

Table I.

Hemo Control, year 2011.

| Women (n=1,043) | Men (n=2,813) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Hb<12.5 g/dL | Hb≥12.5 g/dL | Hb<13.5 g/dL | Hb≥13.5 g/dL | ||||

| Positive | 63 | Positive | 2 | Positive | 23 | Positive | 3 |

| Negative | 133 | Negative | 845 | Negative | 151 | Negative | 2636 |

| Specificity | 99.76% | NPV | 86.40% | Specificity | 99.89% | NPV | 94.58% |

| Sensitivity | 32.14% | PPV | 96.92% | Sensitivity | 13.22% | PPV | 88.46% |

Analysis of data obtained over the first 6 months of 2011 using the invasive Hemo Control method. Data are divided into those for fit and unfit donors, according to the Hb value resulting from the haemocytometry test, and the pre-donation Hb result indicated by the Hemo Control device, divided into positive (Hb value below threshold) and negative (Hb value above threshold). The negative predictive value (NPV) and positive predictive value (PPV) have been calculated.

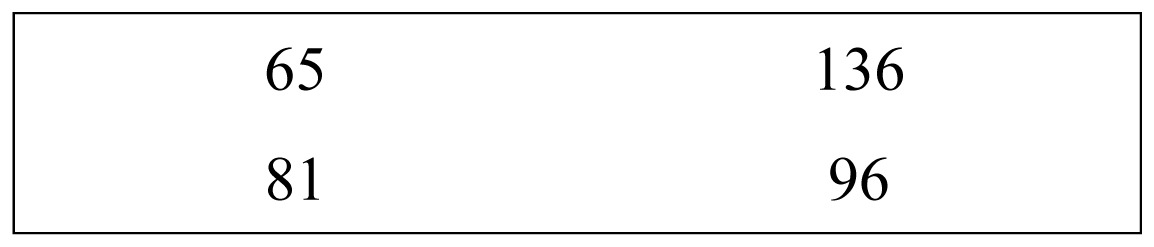

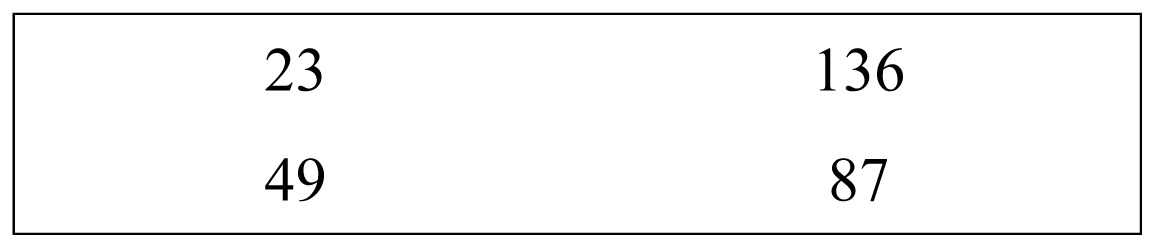

Table II.

NBM 200, year 2012.

| Women (n=1,021) | Men (n=2,945) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Hb<12.5 g/dL | Hb≥12.5 g/dL | Hb<13.5 g/dL | Hb≥13.5 g/dL | ||||

| Positive | 65 | Positive | 40 | Positive | 23 | Positive | 31 |

| Negative | 136 | Negative | 780 | Negative | 136 | Negative | 2,755 |

| Specificity | 95.12% | NPV | 85.15% | Specificity | 98.89% | NPV | 95.30% |

| Sensitivity | 32.34% | PPV | 61.90% | Sensitivity | 14.47% | PPV | 42.59% |

Analysis of data obtained over the first 6 months of 2012 using the non-invasive NBM 200 method. Data are divided into those for fit and unfit donors, according to the Hb value resulting from the haemocytometry test, and the pre-donation Hb result indicated by NBM 200, divided into positive (Hb value below threshold) and negative (Hb value above threshold). The negative predictive value (NPV) and positive predictive value (PPV) have been calculated.

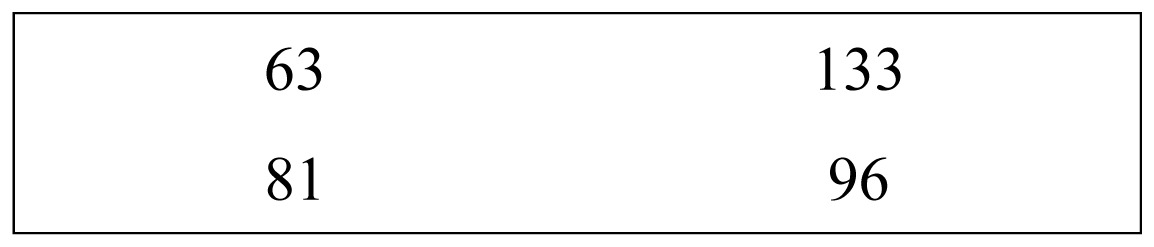

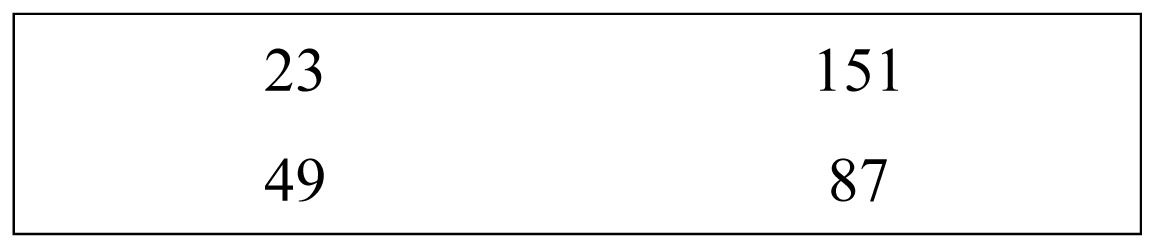

Table III.

NBM 200 + targeted venous sample, year 2013.

| Women (n=1,100) | Men (n=2,895) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Hb<12.5 g/dL | Hb≥12.5 g/dL | Hb<13.5 g/dL | Hb≥13.5 g/dL | ||||

| Positive | 81 | Positive | 7 | Positive | 49 | Positive | 2 |

| Negative | 96 | Negative | 916 | Negative | 87 | Negative | 2,757 |

| Specificity | 99.24% | NPV | 90.51% | Specificity | 99.93% | NPV | 96.94% |

| Sensitivity | 45.76% | PPV | 92.05% | Sensitivity | 36.03% | PPV | 96.08% |

Analysis of data obtained over the first 6 months of 2013 using the strategy of non-invasive NBM 200 corrected by haemocytometry test results on a preliminary venous sample in cases selected by history. Data are divided into those for fit and unfit donors (according to the Hb value resulting from the haemocytometry test using the Coulter Beckman cell-counter on test-tube blood drawn at the start of donation) and also from predonation Hb measured by NBM 200 or Coulter Beckman cell-counter on a pre-donation venous sample, again divided into positive (Hb value below threshold) and negative (Hb value above threshold). The negative predictive value (NPV) and positive predictive value (PPV) have been calculated.

The rise in false positives found in 2012 when the non-invasive method replaced Hemo Control was reduced when the strategy combined the non-invasive method with a venous sample from donors computer-flagged as having critical Hb values.

The number of donors who underwent double venipuncture was 192 out of the 1,100 women (17%) and 197 out of the 2,895 men (7%). Using 2×2 contingency tables to tabulate the number of donors with unacceptable Hb values by haemocytometry and with positive screening (debarred from donating) vs those whose HB proved to be within the acceptable range (negative screening), the values for the three semester values (2011, 2012, 2013) were reviewed separately for women (Table IV) and for men (Table V). On applying Fischer’s statistical test (Software Analyse-it on Excel Microsoft), it can be seen that the difference between 2011 and 2012 is not statistically significant for either men or women, but the difference between 2011 and 2013 and likewise that between 2012 and 2013 were significant.

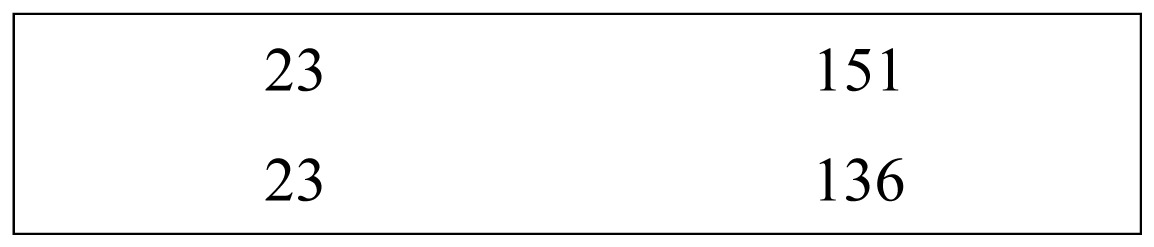

Table IV.

2×2 tables for female donors with low Hb, comparison by year.

| Year | Positive in the screening | Negative in the screening | Total | Difference in proportions | Confidence interval (95%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 |

|

196 | −002 | −0.094 to 0.090 | 1.0000 | |

| 2012 | 201 | |||||

| sum | 128 | 269 | 397 | |||

| 2012 |

|

201 | −0.134 | −0.232 to 0.036 | 0.0102 | |

| 2013 | 177 | |||||

| sum | 146 | 232 | 378 | |||

| 2011 |

|

196 | −0.136 | −0.234 to 0.038 | 0.0095 | |

| 2013 | 177 | |||||

| sum | 144 | 229 | 373 | |||

2×2 contingency tables for the number of female donors with unacceptable Hb values according to a haemocytometry test and with positive screening (debarred from donation), vs those within the norm (negative screening). On testing values for the three semesters (2011, 2012, 2013) it emerged that the differences between 2011 and 2012 are non-significant, while those between 2011 and 2013, and between 2012 and 2013, are statistically significant.

Table V.

2×2 tables for male donors with low Hb, comparison by year.

| Year | Positive in the screening | Negative in the screening | Total | Difference in proportions | Confidence interval (95%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 |

|

174 | −012 | −0.087 to 0.062 | 0.8635 | |

| 2012 | 159 | |||||

| sum | 46 | 287 | 333 | |||

| 2012 |

|

159 | −0.22 | −0.313 to −0.118 | <0.0001 | |

| 2013 | 136 | |||||

| sum | 72 | 223 | 295 | |||

| 2011 |

|

174 | −0.228 | −0.323 to −0.133 | <0.0001 | |

| 2013 | 136 | |||||

| sum | 72 | 238 | 310 | |||

2×2 contingency tables for the number of male donors with unacceptable Hb values according to a haemocytometry test and with positive screening (debarred from donation), vs those within the norm (negative screening). On testing values for the three semesters (2011, 2012, 2013) it emerged that the differences between 2011 and 2012 are non-significant, while those between 2011 and 2013, and between 2012 and 2013, are statistically significant.

Discussion

The finger-prick method is widely used to determine the Hb concentration given its speed, simplicity, transportability, reproducibility and cheapness. The drawbacks of the method are: invasiveness, risk of complications from the finger prick, and over-estimation of Hb concentration in some subjects’ blood (especially young women). This last variability is due both to the form of sampling device used, and to the fact that Hb concentrations from capillary blood are higher than those in venous blood9. Pressing the finger may cause a shift in fluids at the moment of drawing the sample. Thus, pressure on the fingertip to extract enough capillary blood may increase the plasma concentration and falsify the reading. The advantages of the non-invasive method over invasive alternatives are ease of use, in that no calibration is required, a reusable probe vs disposable cuvettes, no trauma to the donor/patient, no risk of infection, no danger of contact with contaminated biological matter, and less scope for human error which the finger prick entails. All in all, the method proves reliable and easy to use10.

The non-invasive method of Hb determination is a valid alternative to the invasive technique, in that it cuts down on consumables (finger-prick needles, micro-cuvettes, disinfectant, etc.) and reduces pain for the donor and the risk of wound complications. The device is appreciated by the donors themselves. However, the correlation between results obtained with NBM 2000 and a cell counter results has been found to be less strong than that between results from a haemoglobin analyser and a cell counter11. On the other hand, although the photometric method on a capillary sample is acceptable for routine donor selection12, it is not always satisfactory, not because of the quality of the measurement technique, but because of the capillary sample itself, which is not always the same quality as a venous sample13–15.

Used on a venous sample, the cell counter is the most reliable method of measuring pre-donation Hb. The disadvantages are the need for qualified staff to draw the sample and manage the device, the time taken to obtain a result, the invasive nature of the method in terms of pain and the risk of phlebotomy complications, not to mention the cost of the hardware.

The results achieved in 2011 and 2012 show that, in our hands, the selective efficiency of the non-invasive method is not substantially different from that of the finger prick technique. We found a reduction in specificity and positive predictive value, which was corrected when we combined venous sampling with use of the cell-counter to check sub-threshold results from the non-invasive method; but no improvement in sensitivity was achieved by the non-invasive over the invasive method, so that the percentage of inappropriate donations remained the same. The new strategy of tagging donors who are frequently borderline has meant that we can route such cases through automatic haemocytometry screening and prevent common donor pathologies such as iron deficit16,17. This strategy brought a significant increase in the negative predictive value and selection sensitivity in the first half of 2013, especially among women donors who, probably for a series of physiological reasons (precarious equilibrium of iron metabolism) and anatomical reasons (vascularisation of the fingers), often result as false negatives in the two screening methods. By opting for the latest strategy, we have been able to retain the non-invasive method and also improve accuracy of donor selection; this reduces the risk of donor anaemia through inappropriate donation, without obliging all donors to undergo double venipuncture. Although it entails about 10% more preliminary blood-drawing, the strategy has proven more popular than the finger-prick method. Its effectiveness in preventing inappropriate donation may improve in time when all active donors have got round to donating twice since the new strategy combines the non-invasive method with an alarm, activated in the computerised donor management system, that is triggered by information from past donations.

Furthermore, would it be possible, as proposed in the past in a different approach18, to admit donors with an historical Hb value on a venous sample without any current pre-donation Hb measurement?

Footnotes

The Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Health Care. Guide to Preparation, Use and Quality Assurance of Blood Components. 17th eds. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cable RG. Hemoglobin determination in blood donors. Transf Med Rev. 1995;9:131–44. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(05)80052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood EM, Kim DB, Miller JP. Accuracy of predonation Hct sampling affects donor safety, eligibility, and deferral rates. Transfusion. 2001;41:353–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41030353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cable RG. Hb screening of blood donors: how close is close enough? Transfusion. 2003;43:306–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duchateau NJ. A comparative study of oxyhemoglobin and cyamethemoglobin determinations by photometric and spectrophotometric methods. Am J Med Technol. 1957;23:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanzetti G. An azide-methemoglobin method for hemoglobin determination in blood. Am J Lab Clin Med. 1966;24:116–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zwart A, Buursma A, Van Kempen EJ, Zijistra WG. Multicomponent analysis of hemoglobin derivatives with reversed-optics spectrophotometer. Clin Chem. 1984;30:373–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belardinelli A, Benni M, Tazzari PL, Pagliaro P. Noninvasive methods for haemoglobin screening in prospective blood donors. Vox Sang. 2013;105:116–20. doi: 10.1111/vox.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel AJ, Wesley R, Leitman SF, Bryant BJ. Capillary versus venous haemoglobin determination in the assessment of healthy blood donors. Vox Sang. 2013;104:317–23. doi: 10.1111/vox.12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinto M, Barjas-Castro ML, Nascimento S, et al. The new noninvasive occlusion spectroscopy hemoglobin measurement method: a reliable and easy anemia screening test for blood donors. Transfusion. 2013;53:766–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim MJ, Parq Q, Kim MH, et al. Comparison of the accuracy of noninvasive haemoglobin sensor (NBM-200) and portable hemoglobinometer (HemoCue) with an automated hematology analyzer (LH500) in blood donor screening. Ann Lab Med. 2013;33:261–7. doi: 10.3343/alm.2013.33.4.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziemann M, Lizardo B, Geusendam G, Schlenke P. Reliability of capillary hemoglobin screening under routine conditions. Transfusion. 2011;51:2714–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulton FE, Nightingale MJ, Reynolds W. Improved strategy for screening prospective blood donors for anemia. Transfus Med. 1994;4:221–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.1994.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers LA, McGuff JM. Evaluation of methods and protocols for hemoglobin screening of prospective whole blood donors. Am J Clin Pathol. 1989;91:309–12. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/91.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radtke H, Polat G, Kalus U, et al. Hemoglobin screening in prospective blood donors: comparison of different blood samples and different quantitative methods. Transf Apher Sci. 2005;33:31–5. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alves da Silva M, Volpe de Souza RA, Meneses Carlos A, et al. Etiology of anemia of blood donor candidates deferred by hematologic screening. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2012;34:356–60. doi: 10.5581/1516-8484.20120092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baart AM, van Noord PAH, Vergouwe Y, et al. High prevalence of subclinical iron deficiency in whole blood donors not deferred for low hemoglobin. Transfusion. 2013;53:1670–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zienann M, Steppard D, Brockmann C, et al. Selection of whole-blood donors for hemoglobin testing by use of historical hemoglobin values. Transfusion. 2006;46:2176–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]