Abstract

Objectives

Many studies have shown strong effects of pregnancy intention on antenatal care behavior in developed countries, but studies from developing settings have shown mixed results. Few investigators have utilized a prospective measure of pregnancy intention. This paper will analyze the association of pregnancy intention and the utilization of antenatal services in two states in northern India using a prospective measure of whether a future pregnancy would be wanted or unwanted.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted between 1998–2003 in Jharkhand and Bihar, India of 2028 women with one or two pregnancies resulting in the live births of singleton infants during the study time period.

Results

Antenatal care utilization was not found to be significantly associated with prospective pregnancy intention (OR=1.18, [95% CI 0.91, 1.52]). Among women who received ANC (N=701), initiation of care was not delayed in unwanted pregnancies. Significant differences existed between the numbers of women who reported their pregnancy unwanted retrospectively, as compared with prospectively. These differences were not associated with the utilization of antenatal care services or timing of care initiation. The exception to these findings were women who consistently reported their pregnancies unwanted both before and after conception, who were twice as likely to delay ANC initiation as women with consistently wanted pregnancies.

Conclusions

Demographic characteristics of reproductive aged women, such as age and parity, seem to predict more closely the use of ANC services than pregnancy intention in Bihar and Jharkhand. Delayed ANC initiation may be significantly associated with unwanted pregnancy, but only when pregnancies were most decisively identified as unwanted.

Keywords: antenatal care, pregnancy intention, prospective measure

INTRODUCTION

Family planning and antenatal care (ANC) services are both highly underutilized in the rural North Indian states of Bihar and Jharkhand. As a consequence, high numbers of unwanted pregnancies are reported (IIPS and Macro 2007), and such pregnancies have been linked to poor maternal health behaviors and infant outcomes (Gipson 2008). A large volume of literature has examined the relationships between unwanted pregnancy and maternal health behaviors, the vast majority of which has been done in the United States. Specific to antenatal care initiation, such domestic studies have largely found a positive association between unwanted pregnancy and delayed initiation of ANC services and decreased frequency of visits (Gipson 2008). Few studies have been completed internationally (Marston and Cleland 2003; Magadi et al. 2000; Gage 1998; Eggleston 2000; Ni and Rossignol 1994), and those that have been done have yielded mixed results. Additionally, all of these studies have been performed utilizing a retrospective measure of pregnancy intention, a method recently questioned by Koenig et al. (2006) and Stephenson et al. (2008), given its measurement limitations.

Unwanted Pregnancy and Antenatal Care Studies in Developed Countries

In the United States and Europe, the effects of pregnancy intentions on maternal behaviors during pregnancy such as smoking, drug and alcohol use, caffeine intake, and vitamin use have generally been shown to be nominal or mixed (Gipson et al. 2008, Korenman et al. 2002, Joyce et al. 2000, Kost et al. 1998). However, significant effects of pregnancy intention on antenatal care behaviors have been demonstrated in developed settings. According to Gipson (2008) and Pagini (2000), numerous studies have found a significant positive effect between unwanted pregnancy and the delayed initiation of antenatal care, as well as the total number of antenatal care visits. Moreover, the delay in initiating antenatal care persisted among unwanted pregnancies, even after controlling for the delayed recognition of the pregnancy, though the total number of antenatal care visits did not (Kost et al. 1998).

The applicability of these findings to a developing setting such as rural India, however, is questionable. For instance, many of these studies found that the antenatal care effects of pregnancy intention were modified by marital status, with an increased effect for unmarried women (Korenman et al. 2002, Kost et al. 1998). Where social standards of early and almost universal marriage are found, such as in Bihar and Jharkhand, the modifying effects of marriage may be nonexistent. Additionally, use of antenatal care is quite normative in the United States and Europe, but this is not the case in northern India. Only 3.5% of births receive late or no antenatal care in the U.S., while in Bihar, 65.9% of pregnant women did not receive a single ANC visit. (National Center for Health Statistics, 2007; IIPS and Macro, 2005) Such dramatic differences in the perception and utilization of antenatal care and the context of unwanted pregnancy question the validity of U.S. studies for a developing setting such as rural northern India.

Unwanted Pregnancy and Antenatal Care Studies in Developing Setting

Far fewer studies exist from developing countries examining the relationships between unwanted pregnancy and antenatal care, and only one study has included an Asian country, the Philippines (Marston and Cleland 2003). Moreover, these investigations have not demonstrated the strong relationships seen in the developed setting studies, instead generating mixed results. For instance, a study performed by Magadi et al. (2000) in Kenya found delayed initiation of antenatal care with unwanted or mistimed pregnancy status, while a separate study by Gage (1998) in Kenya and Namibia found no significant relationship between pregnancy intention and antenatal care initiation during the first trimester (Gipson 2008). Findings from a five country study by Marston and Cleland (2003) highlight the heterogeneity of these associations. Significant associations between delayed antenatal care initiation and unwanted pregnancy were found in two countries (Peru: OR=1.39 [95% CI 1.24, 1.56]; the Philippines: OR=1.21 [95% CI 1.01, 1.46]), while two countries showed no association (Bolivia: OR=1.17 95% [CI 0.98, 1.40]; Kenya: OR=1.20 [95% CI 0.90, 1.59]), and a protective effect was demonstrated in one country (Egypt: OR=0.79 [95% CI 0.66, 0.95]) (Marston and Cleland, 2003).

According to Gipson (2008), the studies already performed in developing settings have significant methodological issues. Kost (1998) demonstrated the importance of controlling for the delayed recognition of pregnancy among those that were unintended; such adjustments were not made in the developing setting studies. Complex modeling was also found to be lacking in these studies. Finally, nearly all of the studies performed to date have utilized a retrospective measurement of pregnancy intention, a measurement approach recently questioned by Koenig et al. (2006).

Prospective vs. Retrospective Measurement of Unwanted Pregnancy

Pregnancy intention has historically been determined retrospectively, either during antenatal visits or immediately following the birth of the baby (Joyce, et al 2002; Lahka and Glasier 2006; Koenig 2006; Schünmann and Glasier 2006; Gipson 2008). Several researchers have identified temporal inconsistencies between pregnancy intention statuses measured during pregnancy and after birth (Joyce, et al 2002; Bankole and Westoff 1998). When compared with prospective pregnancy intention data which was gathered prior to pregnancy conception, Koenig et al. (2006) found that the retrospective measures of pregnancy intention, established during pregnancy, significantly underestimated the proportion of unwanted pregnancies compared with prospective measurements. The inconsistencies in retrospective measurements are largely thought to arise from maternal rationalization of the pregnancy and inevitable birth after conception shifting the wantedness status from unwanted to wanted (Bankole and Westoff 1998; Koenig et al. 2006; Joyce et al. 2000).

Study Objectives

This analysis examines associations between prospectively determined pregnancy intentions and maternal ANC behaviors in the developing setting of rural North India. Pregnancy intention was determined by prospective measures of whether a future pregnancy would be wanted or unwanted. It was hypothesized that women with unwanted pregnancy are less likely to access antenatal care, compared to women with wanted pregnancies. Additionally, among the women who did receive one or more antenatal checkups, it was also hypothesized that initiation of care is delayed more often in unwanted pregnancies.

METHODS

Study Setting

Bihar and Jharkhand are two rural states in eastern North India, with a combined population larger than that of Mexico, the world’s 11th most populous country (Govt. of Bihar, 2001). With the highest poverty rate in India, nearly 40% of Bihar lies below the poverty line, and this poverty is mainly rural (World Bank 2005). The status and autonomy of women in this region is far less than women in South India. Bihar has the worst female literacy statistics in India with 62.1% of women reporting illiteracy; Jharkhand has the third worst female illiteracy rate at 58.5%. A higher proportion of women require permission from their husbands to seek medical assistance, including antenatal care (46.6% and 38.8% in Bihar and Jharkhand respectively vs. 26.8% in the southern state of Tamil Nadu). Many other indicators of female status and autonomy are lower in Bihar and Jharkhand than the country average including household decision making, age at first marriage, higher general fertility rates, and teenage pregnancy rates. (IIPS and Macro 2007).

Antenatal care utilization in Bihar and Jharkhand is significantly lower than the rest of the country. Only 34.1% and 58.9% of mothers in Bihar and Jharkhand, respectively, received at least one antenatal care visit, compared to an average of 94% of mothers in South Indian states. Additionally, the frequency and quality of ANC indicators for the two states, as measured by the number of ANC component services provided at each visit, are significantly worse than those for the whole of India (IIPS and Macro 2007).

Data

The National Family Health Survey-2 (NFHS-2) was carried out in 1998–99 to gather state-level and national-level information on fertility, family planning, infant and child mortality, reproductive health, child health, nutrition of women and children, and the quality of health and family welfare services. During this survey, demographic information was gathered on households, information regarding the quality and availability of village services was collected, and data specific to women’s health issues were gathered, including socio-demographic characteristics; fertility behavior and intentions; use, knowledge and quality of family planning services; and maternal and child health care, among others. A two-stage stratified systemic design was used to ensure representativeness of the sample from the corresponding areas of the state. Response rates for this survey were high for the two states represented in this study, averaging 96.2%. (IIPS and Macro 2007) Questions from this survey provided the basis for the prospective baseline of fertility preferences for the sample population. The cross-sectional data gathered was valuable, but unable to provide insights about temporal associations.

A follow-up study was conducted in 2002–2003 in which women who completed the NFHS-2 survey from four rural Indian states were re-interviewed. Data from two of these states, Bihar and Jharkhand (originally part of Bihar at the time of the NFHS-2 study), are included in this analysis because antenatal care utilization is almost universal in the other two states included in the follow-up survey, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. As previously stated, 34.1% and 58.9% of the population in Bihar and Jharkhand had at least one antenatal visit according to the NFHS-2 survey, compared to over 90% in both Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra (IIPS and ORC Macro 2000).

NFHS-2 follow-up study questionnaire

The questionnaire utilized is shown in Appendix 1. This questionnaire was printed both in English and Hindi, the state language of Bihar and Jharkhand. The survey utilized questions to address respondent background characteristics, reproductive behavior and intentions, quality of family planning care, use of family planning methods and services, antenatal care and immunization, women’s status, and domestic violence, and included an event calendar covering the intervening months between the baseline (NFHS-2) and the follow-up survey (to assess intra-survey pregnancies, pregnancy outcomes, and monthly contraceptive use status). Women who resided in rural areas, were married, were usual residents of the household, had completed the NFHS-2 survey, and were aged 15–39 at the time of the NFHS-2 survey were eligible to participate. Participants were first verbally informed about the follow up interview and they were subsequently asked to provide written consent to be re-interviewed.

Response rates of the NFHS-2 follow-up survey were 80.4% and 81.8% from Bihar and Jharkhand states respectively. Reasons cited for not agreeing to participate in the follow-up study included out-migration, having not actually been interviewed for the NFHS-2 survey, and “located by not re-interviewed”. Analyses showed that non-responders were generally similar to survey responders, but were slightly younger in Bihar and in Jharkhand. Additionally, respondents and non-respondent had similar age distributions until age 39, after which time they diverge. Non-responders were more literate and of higher socio-economic status.

Definition of unwanted pregnancy

For the purposes of this analysis, the determination of future unwanted pregnancies was made prospectively during the initial NFHS-2 survey. In this survey, women were asked when they wanted to bear their next child. Responses were categorized (as soon as possible, within two years, after two years, or do not want more children) and provided the prospective measure of birth intention. Three to four years later, the during NFHS-2 follow-up survey, these same women provided information on recent births, including those occurring during the inter-survey period. Pregnancies occurring during the inter-survey period to women who had indicated that they did “not want more children” or were sterilized on the NFHS-2 survey were defined as unwanted pregnancies.

Previous literature has often stratified wanted/planned, mistimed, and unwanted pregnancies (D’Angelo et al. 2004; Eggleston 2000; Joyce et al. 2000; Kost et al. 1998) Because the mistimed pregnancies are ultimately wanted, and because studies have shown reduced or non-significant differences between the wanted and mistimed compared to the differences between wanted and unwanted groups (Marston and Cleland 2003; Eggleston 2000), in this study mistimed pregnancies were included with wanted pregnancies.

Measurement of antenatal care utilization and initiation

The NFHS-2 follow-up survey asked women a series of questions regarding their most recent pregnancy including whether or not they sought an antenatal checkup, whether or not a health worker visited the home for an antenatal check-up, the gestational month during which first antenatal care was received, and the number of antenatal checkups during the pregnancy (Appendix 1). In this analysis, women who received one or more antenatal checkup visits either in a clinic or at home were considered to have received antenatal care. Additional data describing the gestational month of antenatal service acquisition provided a measure of the timing of these visits. Utilizing the gestational month provided, the timing of these visits was grouped into initiating care during the first five months of gestation or after. Previous studies from developing settings have defined early entry into ANC as 3–6 months (Marston and Cleland 2003; Eggleston 2000); the first five months were chosen to define early entry in this analysis because it was expected that the vast majority of women would recognize their pregnancy by this time.

Analyses

The main outcomes measured in this analysis were a binary measure of any antenatal care service provision (1 received care, 0 care not received) and a binary measure representing the early and late periods of pregnancy during which antenatal care was first provided (categories 0 initiation of care during first 5 months gestation, 1 initiation of care after 5 months). All bivariate analyses were carried out using the z-statistic test of proportion equality. Logistic regressions used explanatory variables identified by previous literature, and the model controlled for age, parity, maternal education, paternal education, an index of autonomy and an index of assets. Only the first, singleton births to women during the study interval were included for the ANC utilization analysis. The autonomy index was scored on a scale of 1 (low) to 3 (high), and it represents a measure of independence felt by the women interviewed. The index was determined by counting the weighted responses to thirteen questions regarding household decision making. An asset index was scored on a scale from 1 (low) to 3 (high). It was created by counting the number of assets held by the household including presence and type of toilet, electricity, radio, television, bicycle, motorcycle, car, refrigerator, and telephone. An asset index score of 1 indicates one household asset, a 2 indicates 2–3 household assets, and a 3 indicates more than four household assets. Some explanatory variables were found to be insignificant at the α=0.05 level, but were maintained in the model to elucidate their relationships in this analysis.

A multivariate logistic regression was executed stepwise to predict the odds of seeking antenatal care in Bihar and Jharkhand. Next, interaction terms between covariates were tested individually; all were found to be insignificant and no interaction terms were included in the final model for antenatal care utilization (Table 3). The model was validated using the Pearson’s χ2 goodness-of-fit test.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds of receiving ANC among women who had 1 or 2 pregnancies during the study interval (n=2028), Bihar and Jharkhand, India:

| Characteristic | Nested Number | Antenatal Care N (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy Intention | ||||

| Wanted | 1,391 | 512 (36.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Unwanted | 637 | 189 (29.7) | 0.72 (0.59, 0.88) | 1.18 (0.91, 1.52) |

| Age | ||||

| <=24 yrs | 624 | 259 (41.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25–29 yrs | 671 | 248 (37.0) | 0.83 (0.66, 1.03) | 1.10 (0.84, 1.43) |

| 30–34 yrs | 482 | 138 (28.6) | 0.57 (0.44, 0.73) | 0.89 (0.64, 1.25) |

| 35–39 yrs | 197 | 44 (22.3) | 0.41 (0.28, 0.59) | 0.79 (0.49, 1.28) |

| 40+ yrs | 54 | 12 (22.2) | 0.40 (0.21, 0.78) | 0.82 (0.39, 1.74) |

| Parity | ||||

| 1–2 children | 544 | 269 (49.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 3–4 children | 754 | 255 (33.8) | 0.52 (0.42, 0.65) | 0.48 (0.37, 0.62) |

| 5–6 children | 448 | 119 (26.6) | 0.37 (0.28, 0.48) | 0.41 (0.28, 0.58) |

| >6 children | 282 | 58 (20.6) | 0.26 (0.19, 0.37) | 0.34 (0.21, 0.54) |

| Maternal Education | ||||

| No edu | 1,695 | 507 (29.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 96 | 41 (42.7) | 1.75 (1.15, 2.65) | 1.07 (0.69, 1.68) |

| Secondary | 213 | 135 (63.4) | 4.06 (3.01, 5.46) | 1.95 (1.36, 2.81) |

| Higher | 24 | 18 (75.0) | 7.03 (2.77, 17.81) | 2.77 (1.00, 7.65) |

| Paternal Education | ||||

| No edu | 964 | 250 (25.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 249 | 75 (30.1) | 1.23 (0.91, 1.67) | 1.14 (0.83, 1.56) |

| Secondary | 619 | 261 (42.2) | 2.08 (1.68, 2.58) | 1.57 (1.23, 2.00) |

| Higher | 196 | 115 (58.7) | 4.05 (2.95, 5.58) | 1.84 (1.23, 2.76) |

| Asset Index | ||||

| Low | 950 | 250 (26.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Med | 849 | 310 (36.5) | 1.61 (1.32, 1.97) | 1.11 (0.85, 1.44) |

| Hi | 229 | 141 (61.6) | 4.49 (3.31, 6.07) | 2.01 (1.42, 2.86) |

| Autonomy Index | ||||

| Low | 712 | 246 (34.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Med | 1,022 | 351 (34.3) | 0.99 (0.81, 1.21) | 1.17 (0.94, 1.45) |

| High | 294 | 104 (35.4) | 1.04 (0.78, 1.38) | 1.51 (1.11, 2.06) |

Bolded terms: significant at α=0.05

A second stepwise logistic regression was carried out in the same manner to predict the timeliness of first antenatal service utilization among women who had received care (Model E). Due to smaller sample sizes, many covariates used in the model were categorized into fewer groups than the previous models (A–D).

Finally, the prospective measures of pregnancy intention gathered during the NFHS-2 survey in 1998/1999 were compared to the retrospective measures of pregnancy intention captured during the NFHS-2 follow up survey. In the NFHS-2 follow up survey, women were asked, “At the time you became pregnant with (NAME OF CHILD), did you want to become pregnant then, did you want to wait until later, or did you not want to become pregnant at all?” Responses were then grouped as either “wanted”, representing the responses “wanted then” and “wanted later”, or “unwanted”, representing the response that the pregnancy was wanted “not at all”. The retrospective analyses in this study were based on the first child born during the study interval, which was also the first child birthed after the participant declared their future pregnancy intentions during the NFHS-2 and the same pregnancy utilized for the prospective analysis. Z-tests of proportionality equality were performed to examine the similarities between prospective and retrospective measures of unwanted pregnancy. All analyses were carried out using Stata 10.0 software (StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

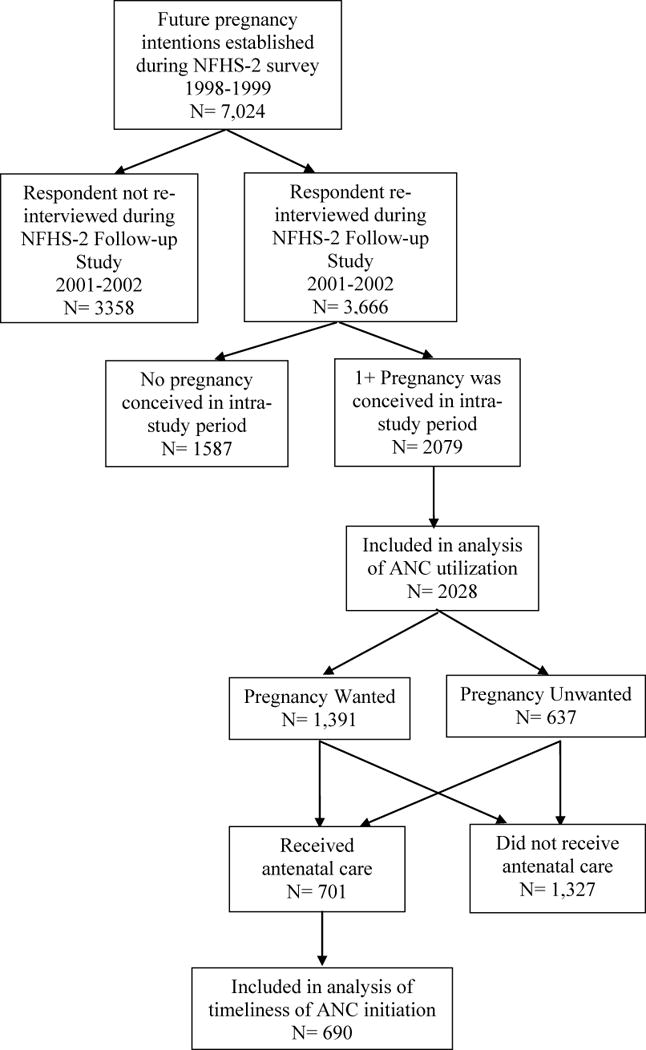

In total, 3666 women from Bihar and Jharkand states were re-interviewed in the follow-up study. Of these interviewees, 2079 women aged 18–49 experienced at least one pregnancy during the inter-survey period. The final study population included 2028 (97.5%) women who had one or two pregnancies and complete data (Figure 1). Unwanted pregnancy accounted for 637 (31%) of pregnancies in this study (Table 1). Approximately 80% of the women included in this study resided in Bihar. Over 83% of women studied reported having no formal education, while over 47% of husbands had no schooling. Thirty-three percent of the households surveyed were identified by NFHS-2 survey classification as members of the scheduled caste or tribe, while an additional 52% of participating households were identified as “other backward class”. The dominant religion was Hindu (81.3%), and Islam was also prevalent (17.6%). Women reporting unwanted pregnancies were significantly more likely to be over the age of 30 than those reporting wanted pregnancies (p=0.000). Having more than four children was also found to be a significant predictor of unwanted pregnancy (p=0.000).

Figure 1.

Table 1.

Demographic indicators of study participants, stratified by prospectively determined pregnancy intention of most recent pregnancy, Bihar and Jharkhand states, India:

| No. (%) | Total (%) | Wanted | Unwanted | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2028 (100.0) | 1391 (68.6) | 637 (31.4) | 0.000 |

| Antenatal Care | ||||

| Yes | 701 (34.6) | 512 (36.8) | 189 (29.7) | 0.080 |

| No | 1327 (65.4) | 879 (63.2) | 448 (70.3) | 0.010 |

| Age (yrs) | ||||

| <=24 | 624 (30.8) | 574 (41.3) | 50 (7.9) | 0.000 |

| 25–29 | 671 (33.1) | 513 (36.9) | 158 (24.8) | 0.005 |

| 30–34 | 482 (23.8) | 231 (16.6) | 251 (39.4) | 0.000 |

| 35–39 | 197 (9.7) | 57 (4.1) | 140 (22.0) | 0.002 |

| 40+ | 54 (2.7) | 16 (1.2) | 38 (6.0) | 0.441 |

| State | ||||

| Bihar | 1620 (79.9) | 1,102 (79.2) | 518 (81.3) | 0.326 |

| Jharkhand | 408 (20.1) | 289 (20.8) | 119 (18.7) | 0.631 |

| Parity | ||||

| 0–2 children | 544 (26.8) | 530 (38.1) | 14 (2.2) | 0.006 |

| 3–4 children | 754 (37.2) | 566 (40.7) | 188 (29.5) | 0.006 |

| 5–6 children | 448 (22.1) | 202 (14.5) | 246 (38.6) | 0.000 |

| >6 children | 282 (13.9) | 93 (6.7) | 189 (29.7) | 0.000 |

| # Born During Study Time Interval | ||||

| 1 child | 1,301 (64.2) | 842 (60.5) | 459 (72.1) | 0.000 |

| 2 children | 727 (35.9) | 549 (39.5) | 178 (27.9) | 0.005 |

| Maternal Education | ||||

| No edu | 1695 (83.6) | 1,178 (82.5) | 547 (85.9) | 0.076 |

| Primary | 96 (4.7) | 76 (5.5) | 20 (3.1) | 0.661 |

| Secondary | 213 (10.5) | 151 (10.9) | 62 (9.7) | 0.796 |

| Higher | 24 (1.2) | 16 (1.2) | 8 (1.3) | 0.297 |

| Paternal Education | ||||

| No edu | 964 (47.5) | 633 (45.5) | 331 (52.0) | 0.055 |

| Primary | 249 (12.3) | 173 (12.4) | 76 (11.9) | 0.912 |

| Secondary | 619 (30.5) | 444 (31.9) | 175 (27.5) | 0.285 |

| Higher | 196 (9.7) | 141 (10.1) | 55 (8.6) | 0.750 |

| Asset Index | ||||

| Low | 1451 (71.6) | 973 (70.0) | 478 (75.0) | 0.997 |

| Med | 364 (18.0) | 259 (18.6) | 105 (16.5) | 0.997 |

| Hi | 213 (10.5) | 591 (11.4) | 54 (8.5) | 0.085 |

| Caste | ||||

| Scheduled caste/tribe | 674 (33.2) | 460 (33.1) | 214 (33.6) | 0.898 |

| “Other backward class” | 1065 (52.5) | 740 (53.2) | 325 (51.0) | 0.508 |

| Other | 289 (14.3) | 191 (13.7) | 98 (15.4) | 0.696 |

| Religion | ||||

| Hindu | 1650 (81.3) | 1,133 (81.5) | 517 (81.2) | 0.885 |

| Muslim | 357 (17.6) | 243 (17.5) | 114 (17.9) | 0.926 |

| Christian | 9 (0.4) | 5 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) | 0.966 |

| Other | 12 (0.6) | 10 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) | 0.948 |

| Autonomy Index | ||||

| Low | 712 (35.1) | 523 (37.6) | 189 (29.7) | 0.052 |

| Med | 1022 (50.4) | 699 (50.3) | 323 (50.7) | 0.905 |

| High | 294 (14.5) | 169 (12.2) | 125 (19.6) | 0.082 |

Bolded terms: significant at α=0.05

Antenatal Care Outcome

Only 701 (35%) of women received at least one antenatal checkup. The unadjusted odds of receiving any antenatal care were significantly lower if the pregnancy was unwanted (OR=0.75 [95% CI 0.61, 0.92]), but this significance was lost in the adjusted model (Tables 2, 3). Women with more than two children were significantly less likely to receive care, regardless of pregnancy intentions. Age and parity were shown to be major confounders of pregnancy intention on antenatal care utilization. Both maternal and paternal education above primary schooling were found to be significant positive predictors of seeking ANC services. Individuals with high asset scores were significantly more likely to receive care, regardless of pregnancy intention, as were women with a high autonomy index (Table 3).

Table 2.

ANC outcomes by prospectively determined pregnancy intention, Bihar and Jharkhand, India:

| Total N (%) |

Wanted N (%) |

Unwanted N (%) |

Crude OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANC | |||||

| No | 1327 | 879 (63.2) | 448 (70.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 701 | 512 (36.8) | 189 (29.7) | 0.72 (0.59, 0.89) | 1.18 (0.91, 1.52) |

|

| |||||

| Mo. of ANC Initiation | |||||

| ≤ 5 mos. | 418 | 310 (61.5) | 108 (58.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| > 5 mos. | 272 | 194 (38.5) | 78 (41.9) | 1.15 (0.82, 1.62) | 1.24 (0.83, 1.85) |

Bolded terms are significant at α=0.05; ANC=antenatal care

Timeliness of antenatal care initiation

Of the 701 women who received antenatal services, 690 (98.4%) were included for the timing of care analysis due to completeness of data. Among these women, 418 (60.6%) received their first antenatal care services during the five months of gestation, while 272 (39.4%) received after the fifth month. Women with unwanted pregnancies did not have delayed care utilization, compared with women who had wanted pregnancies (Table 2). Additionally, no demographic indicators predicted delayed entry to care (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of initiating ANC services after the first five months of gestation (n=690), Bihar and Jharkhand, India:

| Characteristic | Adj OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Pregnancy Intentions | |

| Wanted | 1.00 |

| Unwanted | 1.24 (0.83, 1.85) |

|

| |

| Age (yrs) | |

| <=29 | 1.00 |

| 30+ | 1.01 (0.67, 1.51) |

|

| |

| Parity | |

| 1–3 children | 1.00 |

| 4+ children | 0.90 (0.61, 1.34) |

|

| |

| Maternal Education | |

| No edu+ Primary | 1.00 |

| Secondary+ Higher | 0.82 (0.51, 1.30) |

|

| |

| Paternal Education | |

| No edu+ Primary | 1.00 |

| Secondary+ Higher | 0.71 (0.50, 1.30) |

|

| |

| Asset Index | |

| Low | 1.00 |

| Med | 0.95 (0.63, 1.43) |

| Hi | 0.73 (0.45, 1.18) |

|

| |

| Autonomy Index | |

| Low | 1.00 |

| Med | 0.99 (0.71, 1.39) |

| High | 0.65 (0.39, 1.07) |

Bolded terms: significant at α=0.05.

Retrospective versus prospective pregnancy

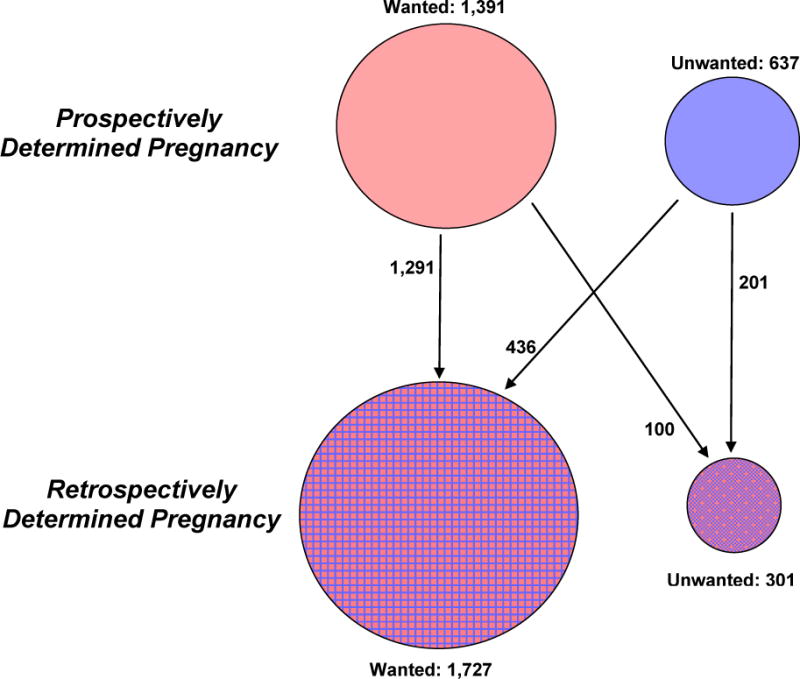

To examine the validity of the prospective measures of pregnancy gathered during the original NFHS-2 and used during this analysis, the prospective measures were compared with the retrospective assessments of the same pregnancies taken later, during the NFHS-2 follow up survey. Significantly fewer women reported retrospectively that their pregnancies were unwanted than prospectively (p=0.000) (Table 5), and in fact, 68% of prospectively measured unwanted pregnancies were later deemed wanted in the retrospective survey (Figure 2). It was somewhat unexpected to find that a full one-third of pregnancies retrospectively identified as unwanted were originally considered wanted in the prospective measure. Similar to the prospective data, the retrospective analysis showed no difference in the odds of antenatal care among women with unwanted pregnancies compared to those with wanted pregnancies (retrospectively OR=1.13 [95% CI 0.83, 1.54]; prospectively OR=1.18 [95% CI 0.91, 1.52]).

Table 5.

Comparison of prospectively reported numbers of unwanted pregnancy (measured on the NFHS-2 survey) with prospectively reported numbers of unwanted pregnancy (measured on the NFHS-2 follow-up survey), Bihar and Jharkhand, India:

| Total | Prospective Unwanted N(%) | Retrospective Unwanted N(%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANC | ||||

| Yes | 701 | 189 (27.0) | 88 (12.6) | 0.008 |

| No | 1327 | 448 (33.8) | 213 (16.1) | 0.000 |

| Mo. of ANC Initiation | ||||

| ≤ 5 mos. | 418 | 108 (25.8) | 46 (11.0) | 0.040 |

| > 5 mos. | 272 | 78 (28.7) | 47 (17.3) | 0.151 |

Bolded terms: significant at α=0.05.

Figure 2.

Diagram showing distribution of prospectively and retrospectively determined pregnancy intentions, Bihar and Jharkhand, India (n=2028)

Women who consistently qualified their pregnancy as either wanted or unwanted, both prior to and after conception (n=1492), were analyzed separately using the same logistic models in an effort to assess the associations of consistently unwanted pregnancies upon antenatal care outcomes. Results showed no difference in utilization of antenatal services among women with consistently unwanted pregnancies compared with women who consistently identified their pregnancies as wanted. Unlike the previous analyses, however, women with consistently unwanted pregnancies were twice as likely to delay ANC initiation, compared to women with consistently wanted pregnancies (consistently reported OR=2.08 [95% CI 1.06, 4.11]); prospectively OR=1.24 [95% CI 0.83, 1.85]); retrospectively OR=1.63 [95% CI 0.98, 2.71]) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of adjusted odds of receiving any ANC and delayed initiation ANC services by definition of pregnancy intention, Bihar and Jharkhand, India:

| Prospectively Unwanted | Retrospectively Unwanted | Consistently Unwanted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N | Adj OR (95% CI) | N | Adj OR (95% CI) | N | Adj OR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||||

| ANC | 2028 | 2028 | 1492 | |||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.18 (0.91, 1.52) | 1.13 (0.83, 1.54) | 1.09 (0.71, 1.67) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Mo. of ANC Initiation | 690 | 690 | 527 | |||

| ≤ 5 mos. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| > 5 mos. | 1.24 (0.83, 1.85) | 1.63 (0.98, 2.71) | 2.08 (1.06, 4.11) | |||

Bolded terms: significant at α=0.05. Reference group for pregnancy intention in all three categories: wanted pregnancies.

DISCUSSION

Results from this analysis indicate that parity best predicts the receipt of antenatal care services in North India, whereas pregnancy intention failed to significantly affect ANC utilization in the final model. The inability of pregnancy intention to predict ANC utilization was in line with some studies (Gage 1998), but not others (Eggleston 2000; Magadi 2000). The importance of parity in predicting antenatal care usage is in keeping with the study by Marston and Cleland (2003), which found that birth order and family size were more important predictors of antenatal care use than pregnancy intention. Though they represent different characteristics of women, age, parity, and pregnancy intention are closely related in many developing settings like North India. Additional models demonstrated that age and parity largely confounded the effect of pregnancy intention in this analysis.

The lack of association between prospectively determined unwanted pregnancy and delayed initiation of ANC in the final adjusted model was not in accordance with published literature (Magadi 2000; Eggleston 2000; Marston and Cleland 2003). However, the results of the same model using only consistently unwanted pregnancies did yield results consistent with previous work. Such findings may indicate that the degree of association between pregnancy intention and antenatal care timeliness may be dependent upon the strength of the mother’s feelings toward the pregnancy. Delayed entry into care by mothers with unwanted pregnancies had been found in previous studies and was hypothesized to result from delayed recognition of pregnancy symptoms and time lost to pregnancy termination (Kost 1998). Indeed, in her analysis of pregnancy intention and maternal antenatal care behaviors, Kost (1998) emphasized the importance of controlling for delayed recognition of pregnancy and/or delays due to pregnancy termination decision making when analyzing the timing of the first ANC visit. Though such controls could not be included in this analysis due to limitations in the survey, the conservative use of the first five months of gestation representing “early” entry into care conceivably allowed for delayed pregnancy realization and decisions to terminate.

Implicit in the definition of unwanted pregnancy as it is used in this analysis is the assumption that women’s prospectively determined reproductive intentions remained fixed throughout the inter-survey period. Results from this analysis indicate that this assumption may be largely correct, but not universal. One hundred (4.9%) women in the study prospectively determined any future pregnancies to be wanted, but after the subsequent birth of a child, unexpectedly retrospectively identified the pregnancy as unwanted. Such findings may illustrate the dynamic nature of pregnancy intentions.

Pregnancy intentions of women with live births were measured in this study, which failed to account for pregnancies which were either spontaneously or intentionally terminated. By not including such pregnancies, sample selection bias may affect the antenatal care utilization rates found in this analysis. Additionally, the grouping of mistimed pregnancies with the wanted pregnancies may have underestimated the relative differences found between unwanted pregnancies and the wanted group. Only women’s pregnancy intentions were sought in the survey, so no information about the pregnancy intentions of husbands was included, which may carry greater weight in this paternalistic society.

Two important aspects of antenatal care were not considered in this study, namely frequency and quality of ANC. Kost (1998) clearly illustrated the expected associations of delayed first antenatal visit with the total number of visits during pregnancy. In Bihar and Jharkhand, women received their first ANC visit at an average 4.4 months, but nearly 40% of women did not initiate care until the sixth month of gestation or later. It is expected that late initiation of care directly impacts the frequency of ANC visits, as women with delayed initiation will have less gestation time to receive the recommended additional three visits. The quality of ANC has been shown to vary across India, and quality of care in northern states including Bihar and Jharkhand was found to be substandard (Rani, Bonu and Harvey 2008). With no measures of the quality of care included in the NFHS-2 follow up study survey (Appendix A), quality assessment was not possible in this study. It is probable, however, that for the 33% of women in this study who received ANC, the quality of the service was most likely severely lacking.

According to Gipson (2008), previous studies from developing settings have found that pregnancy intentions are related to maternal antenatal care behaviors, but such findings have been modest, varied greatly by country context, and lacked stringent methodology. The results of the adjusted analyses in this paper did not support Gipson’s assessment, finding no association of prospective pregnancy intention status upon antenatal care utilization. The effects of pregnancy intention upon utilization of care were found to be heavily confounded by the effects of age and parity, perhaps indicating that such demographic measures may be better predictors of antenatal care usage. In the timeliness of care analysis, a no association between prospectively defined unwanted pregnancy and delayed ANC initiation was found, yet when only pregnancies deemed consistently wanted or unwanted were considered, delayed entry to care was indeed established. Thus, it is possible that the effects of pregnancy intention upon the timeliness of ANC initiation may be related to the strength of the feelings toward the pregnancy, and mothers with the strongest feelings of pregnancy unwantedness may be at the highest risk of late care. These findings illustrate the complexity of pregnancy intention and maternal ANC behaviors.

CONCLUSIONS

Fundamentally, utilization rates of antenatal care services require improvement throughout Jharkhand and Bihar, regardless of pregnancy intention. In this analysis, it was shown that maternal antenatal care behaviors were not affected by the mother’s desire for a future pregnancy prior to its conception. With the health and survival benefits of antenatal care clearly established for both mother and child, this study highlights the importance of reducing maternal and child morbidity and mortality by targeting women with demographic profiles showing reduced likelihood of ANC utilization, such as having more than four children and an age above 30 years. Results also indicate that women with the strongest feelings of unwantedness toward their pregnancies had delayed entry to care, highlighting a vulnerable subset of mothers with unwanted pregnancies. This study demonstrated inadequacies in family planning among study participants, as 37% of the women re-interviewed during the (n=2079) had two or more prospectively determined unwanted pregnancies during the intra-survey time period. If the utilization of antenatal care dramatically increases, such as has in South India (Rani 2008; IIPS and Macro 2007), perhaps incorporating family planning referrals and/or services into antenatal visits may help to prevent additional unwanted pregnancies. Finally, retrospective measures of pregnancy intention were found to underreport the proportion of unwanted births in this study; as validated in other recent studies (Koenig 2006; Stephenson 2008), prospective measures of fertility preferences are preferred.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Lindsey Barrick, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N Wolfe St., Suite E4527, Baltimore, MD 21205.

Michael A Koenig, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N Wolfe St., Room E4152, Baltimore, MD 21205.

References

- Bankole A, Westoff CF. The consistency and validity of reproductive attitudes: evidence from Morocco. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1998;30(4):439–455. doi: 10.1017/s0021932098004398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. Prenatal Care. National Center for Health Statistics; Page updated March 31, 2008. Page accessed April 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo DV, Gilbert BC, Rochat RW, Santelli JS, Herold JM. Differences between mistimed and unwanted pregnancies among women who have live births. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36(5):192–197. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.192.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggleston E. Unintended pregnancy and women’s use of prenatal care in Ecuador. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51(2):1011–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage AJ. Premarital childbearing, unwanted fertility and maternity care in Kenya and Namibia. Population Studies. 1998;52(1):21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Studies in Family Planning. 2008;39(1):18–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Bihar. Census Statistics. http://gov.bih.nic.in/Profile// Accessed April 16, 2008.

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), 1998–99: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India: Volume I. Mumbai: IIPS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce T, Kaestner R, Korenman S. On the validity of retrospective assessments of pregnancy intention. Demography. 2002;39(1):199–213. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce T, Kaestner R, Korenman S. The effect of pregnancy intention on child development. Demography. 2000;37(1):83–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Acharya R, Singh S, Roy TK. Do current measurement approaches underestimate levels of unwanted childbearing? Evidence from rural India. Population Studies. 2006;60(3):243–256. doi: 10.1080/00324720600895819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenman S, Kaestner R, Joyce T. Consequences for infants of parental disagreement in pregnancy intention. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2002;34(4):198–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost K, Landry DJ, Darroch JE. Predicting maternal behaviors during pregnancy: Does intention status matter? Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30(2):79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakha F, Glasier A. Unintended pregnancy and use of emergency contraception among a large cohort of women attending for antenatal care or abortion in Scotland. Lancet. 2006;368(9549):1782–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69737-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magadi MA, Madise NJ, Rodrigues RN. Frequency and timing of antenatal care in Kenya: Explaining the variations between women of different communities. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51(4):551–561. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00495-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston C, Cleland J. Do unintended pregnancies carried to term lead to adverse outcomes for mother and child? An assessment in five developing countries. Population Studies. 2003;57(1):77–93. doi: 10.1080/0032472032000061749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni H, Rossignol AM. Maternal deaths among women with pregnancies outside of family planning in Sichuan, China. Epidemiology. 1994;5(5):490–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnini DL, Reichman NE. Psychosocial factors and the timing of prenatal care among women in New Jersey’s HealthStart program. Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32(2):56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenatal Care. National Center for Health Statistics; Dec 31, 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/prenatal.htm. Accessed April 3, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rani M, Bonu S, Harvey S. Differentials in the quality of antenatal care in India. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2008;20(1):62–71. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfe E. Cause or consequence?: Exploring causal links between attachment and depression. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2007;26(9):1048–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Schünmann C, Glasier A. Measuring pregnancy intention and its relationship with contraceptive use among women undergoing therapeutic abortion. Contraception. 2006;73(5):520–4. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp: Stata Statistical Software: Release 10.0. Stata Corporation; College Station, TX: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson R, Koenig MA, Acharya R, Roy TK. Domestic violence, contraceptive use and unwanted births in rural India. Studies in Family Planning (forthcoming, 2009) doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Bihar: towards a development strategy. The World Bank; 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.